Article MT106 - from Musical Traditions No 3, Summer 1984

Música Chicana takes off

The intense deejay attacks his San Antonio radio KEDA audience with the rapid-fire fervor of a Latino Wolfman Jack. As his voice rasps and races over the introduction to the next song, the same basic rap is being repeated on other Spanish language radio stations everywhere from Texas' Rio Grande Valley up to Chicago and out to California.  "All right," goes the deejay's in-between-song patter, "this is Güero Polkas con el nuevo éxito de Little Joe y La Familia." What Güero Polkas is getting ready to spin on the ol' turntable, and what other stations are playing more and more of is Música Chicana, the fastest growing Latin music sound in the US. Yes, salsa is bigger and it too is growing. But Música Chicana, with its reliance on an old time polka beat has burst from a local Texas phenomenon that many Latinos had considered rancheron into a new widespread source of cultural pride and joy.

"All right," goes the deejay's in-between-song patter, "this is Güero Polkas con el nuevo éxito de Little Joe y La Familia." What Güero Polkas is getting ready to spin on the ol' turntable, and what other stations are playing more and more of is Música Chicana, the fastest growing Latin music sound in the US. Yes, salsa is bigger and it too is growing. But Música Chicana, with its reliance on an old time polka beat has burst from a local Texas phenomenon that many Latinos had considered rancheron into a new widespread source of cultural pride and joy.

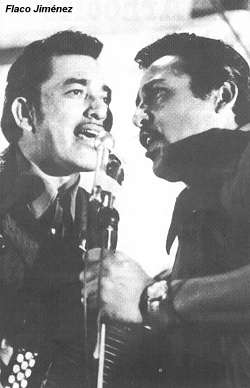

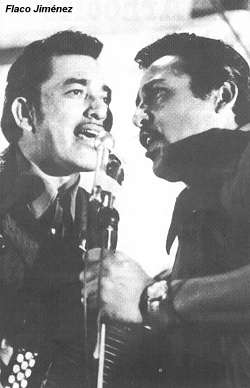

With the strumming rhythm of the sound blaring behind him, a young patron of a Latin discotheque in San Antonio tries to explain: "Before, a lot of people used to be embarrassed by polka music. It was something only for old people to listen to and something for 'wetbacks'. But now we aren't ashamed of who we are any more. When I hear Little Joe or Jimmy Edward or even older guys like Flaco Jiménez I think 'hey, that's part of me.' And it's just as important to me as rock music." Around him while the young man talks, a chicly dressed crowd of dancers is enthusiastically proving his point as they stick their backsides out in the best Música Chicana style and dance in a fashion that is nearly a carbon copy of the steps their grandparents used in the 1920s and '30s.

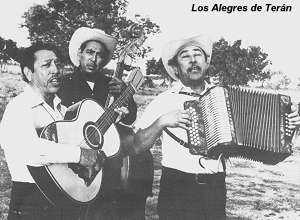

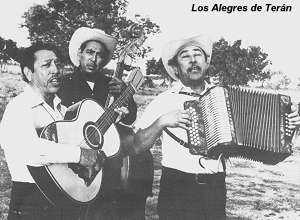

The music they are dancing to shows the same multicultural influences as Güero Polkas' radio patter. The lyrics are mostly Spanish with a few English words thrown in here and there. If the tune is by a younger artist like Little Joe or Jimmy Edward, the performance will have rock influences like electric guitars and even synthesizers. A record by older musicians like Los Alegres de Teran will sound more basic and obviously Latin but it will still be a far cry from the typical Mexican mariachi tune. The one thing both old and new Música Chicana styles have in common is the polka rhythm. Whether it's played on an old-fashioned button-style accordion or the latest synthesizer keyboard, the basic one-two bass-strum rhythm is Música Chicana's backbone.

Actually Música Chicana goes by several aliases. In Texas where the music has its roots it is known as the Tex-Mex sound. In other parts of the nation, it's referred to as the Norteña style,  since influences from northern Mexico often creep into the Músical approach. But the term Música Chicana sums up what the sound is about the music played and enjoyed by Americans of Mexican descent - Chicanos.

since influences from northern Mexico often creep into the Músical approach. But the term Música Chicana sums up what the sound is about the music played and enjoyed by Americans of Mexican descent - Chicanos.

The exact size of Música Chicana's audience is unknown. But there are plenty of indicators of its popularity. In one month, a station like Radio KEDA, with an average 67,000 listeners, makes $35,000 in advertising revenue. An estimated 356 radio stations located throughout the nation play some Música Chicana daily. Its audience is any place where there is a significant Mexican American population. That includes the entire Southwest, in addition to the Pacific Coast states and large cities in the Midwest. There are more than 50 professional and semiprofessional bands just in the South Texas area. And, in one year, Amen Records, only one of the top five Música Chicana labels in Texas, can expect to gross $250,000.

An outsider unfamiliar with salsa and Música Chicana might assume that they are similar. But as fans of both sounds know, the dissimilarity between the two styles of Latin music is as obvious as the difference between a plate of Puerto Rican lechon and Mexican enchiladas. It goes back to salsa's and Música Chicana's origins. In salsa, the music is built around the rhythm established by the congas, bongos and timbales: in Música Chicana, the accordion and bajo sexto guitar set the pace and melody. While salsa's complicated rhythms stem from Cuban and Puerto Rican roots which in turn go back to Africa, Música Chicana is tied to the European polka beat.

Its roots can be traced most importantly to New Braunfels, Texas, a small town 30 miles north of San Antonio inhabited largely by the descendants of German immigrants. During the early part of the 20th Century, large numbers of Mexican immigrants worked on the farms surrounding the community. Flaco Jiménez, today's acknowledged accordion king of Música Chicana, remembers: "My father would go to New Braunfels when the Germans were holding their dances and listen to the bands.  Later, he'd try to play the tunes he heard on his accordion. After a while, he and others started writing their own polkas, but they still had that German polka beat."

Later, he'd try to play the tunes he heard on his accordion. After a while, he and others started writing their own polkas, but they still had that German polka beat."

During the same years Santiago Martinez was listening to German bands oom-pah-pah into the night, two other musicians, performing on both sides of the border, were establishing Música Chicana's basic sound. Los Alegres de Teran's Eugenio Abrego and Tomas Ortiz took the revolutionary step of adding vocals to what had been exclusively instrumental music for dances. Their style was labeled Norteña and became well-known throughout Mexico, Latin America and in every part of the US where Mexican Americans live. They became a major influence on future Música Chicana practitioners. By the end of the 1930s, Música Chicana records were being cut and distributed throughout South Texas.

The sound remained unchanged until the late '50s when rock influences gave it a new boost. Bandleaders like Little Joe Hernández, Agustín Ramirez and Sonny Ozuna took the traditional polka melodies and adapted them, dropping accordions and adding horn arrangements, drums and electric instruments. Along with different instruments and arrangements, the newer groups incorporated jazz, rock and country-western.

And the lyrics dealt more and more with all aspects of the Mexican American culture. Whether it was a song about marijuana laws, brutality by the Texas Rangers or Chicano pride, the issues were covered by Música Chicana. Joe Hernández, known as Little Joe to fans he's collected since the late '50s, is a good example of the artists who brought a message to their music. Though he is now one of Música Chicana's most popular performers and has his own Buena Suerte record label, the one-time migrant worker will still remind an 8,000-member audience of what it was like during the '50s and early '60s when Mexican Americans were not allowed to speak Spanish in public schools and were discriminated against in a variety of other ways. "Nobody who really knows anything will say Chicanos have equal rights now," says Joe. "We still have to look out for ourselves and be proud of our music and the way we live." His audiences respond because they are touched personally. "When I was feeling poor, Little Joe had a song about it," says one fan. "When I came back from Vietnam, he had a song, and, when I became proud of being a Chicano, Little Joe was singing along."

By 1965 bolstered by its new topicality and sound the music had become readily available in Latin record markets throughout the Southwest and parts of California. At the same time, Música Chicana started to nose its way onto the airwaves as more Spanish language radio stations with Mexican American audiences gave it airplay. Previously, almost all those stations had kept to a rigid format of music from Mexico. While some stations gradually increased the amount of exposure for Música Chicana, other stations gambled with almost straight Música Chicana formats. Güero Polkas (who is known as Richard Davila on his birth certificate) explains: "When KEDA started in 1966, we decided to give emphasis to the local artists who were turning out some great music. We thought it would be ridiculous to act like snobs toward our own musicians." KEDA's gamble paid off, and by 1974 it opened KCCT in Corpus Christi, which also features Música Chicana.

Meanwhile, as Música Chicana's popularity continued to grow, a fourth generation of musicians sprouted and added their own ingredients to an old formula. Singers like Jimmy Edward reached back to the 50s ballad styles and translated the lyrics of the oldies into Spanish. The People Orchestra and Matias even added disco and salsa touches to their music to attract Música Chicana fans among today's Chicano teenagers. "Even though it would probably be easier to switch to Top 40 music, we feel like we need to remind the kids about their heritage," says David Márez, lead vocalist of People. "So we take the music and add our own touches, but we're still polkeros in the old sense and our music still has that same old beat."

Don't let the idea that Música Chicana sticks to a strict one-two beat give the impression that its performers are Músical midgets. Accordionists like Esteban Jordan can lay a complicated jazz melody on top of a polka that will rival salsero Eddie Palmieri's complex piano flights of fantasy. And along with musical creativity, there's another important ability shared by salseros and polkeros. Both styles prize spontaneous emotion. Like the cries of "vaya" that a timbalero arouses after he finishes an inspired solo, an accordionist will be met with appreciative shouts of "ajúa" and "huepa" if he moves his listeners with a particularly soaring improvisational solo. Says Tony de la Rosa, a virtuoso accordionist who's played the Música Chicana circuit for the last 20 years: "The whole thing is, when I play the accordion a special way, people can feel it and it touches them somewhere."

The most obvious place it touches them is the feet - discotheques in almost every city with a sizeable Mexican American population feature Latin music nights in which polkas are sandwiched between the latest Santana and salsa hits. Meanwhile, local clubs tucked away in Mexican American barrios which cater to a middle-aged clientele, often find themselves bursting at the acoustic seams on weekends and especially on Sunday afternoons for dances known as tardeadas. Traditional Música Chicana bands, composed of an accordion, a bajo sexto guitar, drums and bass, pump out the latest hits and the old standards as couples dance from early afternoon to midnight.

Música Chicana's big event is held once a year, usually during July in San Antonio's Convention Center. It's Super Dance, a seven-hour extravaganza roughly equivalent to an appearance by the Fania All Stars for a salsa fan. Top performers like Little Joe, Sonny Ozuna and Jimmy Edward always come to San Antonio for the Super Dance. An estimated 8,500 fans crowded into the center last year to hear the all-star lineup which included country singer Freddy Fender, one of the few South Texas Chicano musicians to win a national audience. But although Fender was warmly received, the star of the evening was Little Joe.

His set summed up what Música Chicana is all about. First, he and his 10-piece orchestra went through some of the polkas his fans have been listening to for the last 15 years. Then, shedding his tuxedo coat, he performed a driving version of the rock standard Knock on Wood. In fact, during that number, the super dance stopped being a dance. Almost half the audience crowded around the stage to watch the virtuoso performance. When the set was over, the perspiring singer could barely squeeze down the stage's steps. Female admirers crowded around him and his singing partner Johnny Hernández in a manner that would have flattered a rock superstar.

Such fans are no longer confined to Texas. But while other states produce Música Chicana artists, it is still the ones from Texas who dominate the sound. Manuel Guerra, executive producer for Amen Records in San Antonio, claims proudly that "the other musicians just follow the Texas musicians' styles. It all started here. Just like the flour tortilla, the music is something that began in Texas and traveled with Chicanos wherever they went."

The next question is: Can the excitement Música Chicana creates be duplicated outside the Mexican American culture? The consensus in the trade is that it is more than possible, if certain changes are made in the way the business side of the music is organized. Already performers like Flaco Jiménez are finding a completely new audience they would never have dreamed of playing for two or three years ago. For most of his life, Jiménez has spent his time looking out over a sea of dancers' heads as he pumped out the music his father helped develop. His audiences always consisted of working-class Mexican Americans, who strongly identified with his earthy music. Rut now he's seeing more than a few blonde heads, belonging to college students, bobbing along with the regulars.

He developed a cult of college-age fans following his US and European tours with rock performer Ry Cooder. Jiménez was signed on by Cooder for his Chicken Skin Music album, because the rock musician was looking for another sound to add to his eclectic record which already contained Hawaiian and gospel influences. Jiménez says he's currently waiting to see if he will do an entire album of his style of music on the Warner Brothers label.

If Jiménez makes an album for a major record label, it will be a first for a Música Chicana artist. Currently, all the music is on regional label recordings, ranging in quality from garage operations to advanced multi-track studios. But none of the labels is on a national level in technical know-how or in promotion or distribution. As a result, Música Chicana's exposure is still confined to Spanish language radio and television. While other Latin music styles, like the mambo and samba, have received national attention, there's never been anything like a polka craze.

The problems that have kept Música Chicana from getting national exposure also include a lack of organization. "The trouble is simply that we bargain like we're in the local market," complains Joe Hernández. "One guy will always say he'll sell an album a dollar cheaper. So there are no set prices, and we never really get ahead." But there are indications that the industry is changing. For the first time, a market survey is being carried out in Texas to determine the size of Música Chicana's market and exactly what styles will sell best. The survey is financed with federal funds received by Zavala County. If the survey proves there is a large enough market, says Zavala County Judge José Angel Gutiérrez, the South Texas county will apply for additional funds to help finance a record-pressing plant and studios in order to aid the county's economic development. At the same time, the major Música Chicana labels in Texas have started forming cooperative-like associations to aid each other's projects. "From what I understand, that's what happened with Motown Records in Detroit. The people realized no one was going to do it for them; so they got together and did it for themselves," says Judge Gutierrez.

Is mainstream America ready for Música Chicana? A number of performers hope so but only if their music is accepted on its own terms. "A lot of Anglos have the impression this is Mexican music. It's not. It's music played by Americans of Mexican descent, and that makes a world of difference in the way we sound," says People's Márez. And there is little inclination to change merely to meet a broader market. "The thing about our musicians is that they've grown up in between honky and funky, meaning country and soul music. So our music has all the influences and a little something for everybody. There's no doubt it could catch on," says Little Joe. "But no matter what happens, Música Chicana will always be ours."

Ben Tavera-King

This article first appeared in Nuestro magazine, Feb 1978, and is reprinted with the permission of the author.

Article MT106

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 1.10.02

"All right," goes the deejay's in-between-song patter, "this is Güero Polkas con el nuevo éxito de Little Joe y La Familia." What Güero Polkas is getting ready to spin on the ol' turntable, and what other stations are playing more and more of is Música Chicana, the fastest growing Latin music sound in the US. Yes, salsa is bigger and it too is growing. But Música Chicana, with its reliance on an old time polka beat has burst from a local Texas phenomenon that many Latinos had considered rancheron into a new widespread source of cultural pride and joy.

"All right," goes the deejay's in-between-song patter, "this is Güero Polkas con el nuevo éxito de Little Joe y La Familia." What Güero Polkas is getting ready to spin on the ol' turntable, and what other stations are playing more and more of is Música Chicana, the fastest growing Latin music sound in the US. Yes, salsa is bigger and it too is growing. But Música Chicana, with its reliance on an old time polka beat has burst from a local Texas phenomenon that many Latinos had considered rancheron into a new widespread source of cultural pride and joy.

since influences from northern Mexico often creep into the Músical approach. But the term Música Chicana sums up what the sound is about the music played and enjoyed by Americans of Mexican descent - Chicanos.

since influences from northern Mexico often creep into the Músical approach. But the term Música Chicana sums up what the sound is about the music played and enjoyed by Americans of Mexican descent - Chicanos.

Later, he'd try to play the tunes he heard on his accordion. After a while, he and others started writing their own polkas, but they still had that German polka beat."

Later, he'd try to play the tunes he heard on his accordion. After a while, he and others started writing their own polkas, but they still had that German polka beat."