By 1900 the practice of Morris dancing in a traditional context was almost defunct in the south Midlands region of England, after more than three centuries during which it had been a widespread element in working class cultural activity

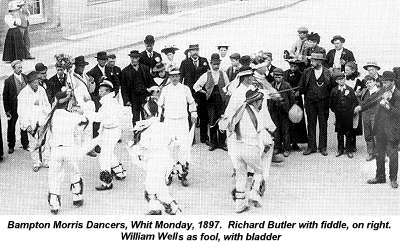

By 1900 the practice of Morris dancing in a traditional context was almost defunct in the south Midlands region of England, after more than three centuries during which it had been a widespread element in working class cultural activity ![]() 1. The particular form of the dance in this region, an area comprising Oxfordshire and the adjacent counties, typically involved six dancers, in a performance formation of two lines of three, plus various ancillary characters such as fool and cake/sword bearer. The roles performed by the latter two characters involved, respectively, amusing the audience with witty and often crude remarks, gestures and antics, and offering a morsel of cake in exchange for a cash contribution. The most frequent time of appearance for the dance was Whitsun, but over the centuries many diverse seasons and occasions - Christmas Easter, weddings, harvest celebrations and the like - had witnessed performances.

1. The particular form of the dance in this region, an area comprising Oxfordshire and the adjacent counties, typically involved six dancers, in a performance formation of two lines of three, plus various ancillary characters such as fool and cake/sword bearer. The roles performed by the latter two characters involved, respectively, amusing the audience with witty and often crude remarks, gestures and antics, and offering a morsel of cake in exchange for a cash contribution. The most frequent time of appearance for the dance was Whitsun, but over the centuries many diverse seasons and occasions - Christmas Easter, weddings, harvest celebrations and the like - had witnessed performances.

At Bampton, a small town in Oxfordshire, morris dancing continues to be practiced by three distinct dance sets. Several of the current participants can lay claim to family traditions of dancing over three or more generations. Among both the dancers and other inhabitants of the town, and depending upon who you happen to be speaking to at the time, it is commonly believed that there has been an unbroken tradition of indigenous performance of up to six hundred years.  This supposed longevity generates intense feelings of pride, jealousy and rivalry. Earlier this century the claims tended to be rather more modest, generally amounting to two or three hundred years

This supposed longevity generates intense feelings of pride, jealousy and rivalry. Earlier this century the claims tended to be rather more modest, generally amounting to two or three hundred years ![]() 2. The first contemporary evidence of the existence of a dance side at Bampton dates only from 1847, however, when the local incumbent wrote rather disparagingly of the dancers' annual performances

2. The first contemporary evidence of the existence of a dance side at Bampton dates only from 1847, however, when the local incumbent wrote rather disparagingly of the dancers' annual performances ![]() 3. This source implies a tradition in full flourish, and certainly not one which had been recently established. A more reasonable claim to chronological accuracy perhaps lies in statements made during the 1920s and earlier by men who believed that members of their families had participated as dancers for three or four generations

3. This source implies a tradition in full flourish, and certainly not one which had been recently established. A more reasonable claim to chronological accuracy perhaps lies in statements made during the 1920s and earlier by men who believed that members of their families had participated as dancers for three or four generations ![]() 4. Indeed, the birth dates of the earliest recorded participants, suggest that they would have been of a suitable age for dancing during the final decade of the eighteenth century

4. Indeed, the birth dates of the earliest recorded participants, suggest that they would have been of a suitable age for dancing during the final decade of the eighteenth century ![]() 5.

5.

This article does not, however, seek to establish chronological credentials for the dancing tradition at Bampton. Rather, its aim is to examine the role played by successive fiddle players within that performance context, and finally to offer some biographical details concerning Arnold Woodley, a musician still active at that location, and perhaps the finest living traditional fiddle player in southern England today.

The performance of morris dancing implies the participation of one or more musicians . Many different types of instrument have seen service as an accompaniment to the dance in the south Midlands in the past, among them the flute, tin whistle, banjo, tambourine, side drum, and, later in the nineteenth century, free reed instruments such as the melodeon and concertina ![]() 6. In most of the early accounts, however, the standard accompaniment was provided by the combination of three-holed pipe (known variously as whittle, whit, whistle, or fife) and drum (tabor or dub), both of which were played simultaneously by the same musician. No recordings of traditional morris musicians playing this combination exist, but we can assume that the regular rhythm produced by the drum would have taken precedence over the melodic accuracy of the tune being played on the pipe. One characteristic of the southern English form of morris is the wearing of multiple bells on the shins. These sound loudly while dancing and the dancers need to hear the music above this noise; at the very least the rhythmic pulse has to be clearly audible. These demands made the pipe and drum an ideal accompaniment, but the general decline in the popularity of this instrumental combination meant that by the middle of the nineteenth century the majority of sides which remained active were dancing to music in which the fiddle was pre-eminent

6. In most of the early accounts, however, the standard accompaniment was provided by the combination of three-holed pipe (known variously as whittle, whit, whistle, or fife) and drum (tabor or dub), both of which were played simultaneously by the same musician. No recordings of traditional morris musicians playing this combination exist, but we can assume that the regular rhythm produced by the drum would have taken precedence over the melodic accuracy of the tune being played on the pipe. One characteristic of the southern English form of morris is the wearing of multiple bells on the shins. These sound loudly while dancing and the dancers need to hear the music above this noise; at the very least the rhythmic pulse has to be clearly audible. These demands made the pipe and drum an ideal accompaniment, but the general decline in the popularity of this instrumental combination meant that by the middle of the nineteenth century the majority of sides which remained active were dancing to music in which the fiddle was pre-eminent ![]() 7.

7.

A local newspaper reported the morris sides performing in the streets of Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, at Whitsun, 1842, and noted: ' ... the primitive harmony of the "pipe and tabor" forms their music generally, although some parties introduce the more modern innovations of violin and tambourine ... ![]() 8. This combination of instruments may be seen as an attempt to replicate the all-important rhythm formerly provided by the tabor. Evidence of instruments used to accompany morris dancing in the region during the nineteenth century is patchy, but there are hints of the use of the tambourine in conjunction with the fiddle at various locations.

8. This combination of instruments may be seen as an attempt to replicate the all-important rhythm formerly provided by the tabor. Evidence of instruments used to accompany morris dancing in the region during the nineteenth century is patchy, but there are hints of the use of the tambourine in conjunction with the fiddle at various locations.  At Bampton itself, a newspaper account of the Whit Monday dancing in 1877 noted that 'the morris dancers busily tripped the "light fantastic toe" to the sound of fiddle and tambourine.'

At Bampton itself, a newspaper account of the Whit Monday dancing in 1877 noted that 'the morris dancers busily tripped the "light fantastic toe" to the sound of fiddle and tambourine.' ![]() 9

9

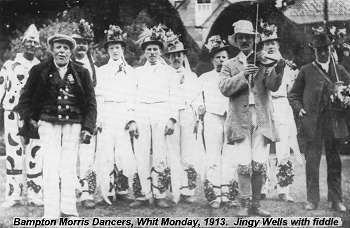

The enthusiasm of a later Bampton fiddler, William Nathan 'Jingy' Wells (1868-1953), resulted in a wealth of historical recollections of the morris in his home town, including a list of musicians who played for performances there from 1840 onwards ![]() 10. I have already noted the widespread early use of the pipe and drum for morris Wells' great grandfather, Thomas Radband (1776-1854), had played them around the turn of the eighteenth century - and it comes as no surprise to find that the earliest musicians on Wells' list were pipers. The first fiddler to perform with the Bampton side may have been Richard Ford, 'about 1851'

10. I have already noted the widespread early use of the pipe and drum for morris Wells' great grandfather, Thomas Radband (1776-1854), had played them around the turn of the eighteenth century - and it comes as no surprise to find that the earliest musicians on Wells' list were pipers. The first fiddler to perform with the Bampton side may have been Richard Ford, 'about 1851' ![]() 11. Wells appears to have listed Ford as a piper in one of his manuscript reminiscences, but on other occasions noted older informants' memories of him as 'a wonderful fiddler'

11. Wells appears to have listed Ford as a piper in one of his manuscript reminiscences, but on other occasions noted older informants' memories of him as 'a wonderful fiddler' ![]() 12. Another musician recalled from the 1850s, John Potter of Stanton Harcourt, was also noted as accompanying the morris on pipe and drum 'about 1856', but he too is known to have played the fiddle

12. Another musician recalled from the 1850s, John Potter of Stanton Harcourt, was also noted as accompanying the morris on pipe and drum 'about 1856', but he too is known to have played the fiddle ![]() 13. we cannot therefore be certain when the fiddle was first used to accompany the dancing, although the presence of a fiddler at Whit performances in the late 1850s and early 1860s was clearly regarded by some as an unwelcome novelty. A newspaper account of 1858 noted that ' ... The dancing was very creditably performed, but we cannot approve of the substitution of a squeaking fiddle for the appropriate, and to our mind, orthodox 'tabor and pipe' ... '

13. we cannot therefore be certain when the fiddle was first used to accompany the dancing, although the presence of a fiddler at Whit performances in the late 1850s and early 1860s was clearly regarded by some as an unwelcome novelty. A newspaper account of 1858 noted that ' ... The dancing was very creditably performed, but we cannot approve of the substitution of a squeaking fiddle for the appropriate, and to our mind, orthodox 'tabor and pipe' ... ' ![]() 14. The same correspondent reported in 1860 that ' . . The old 'tabor and pipe' and the 'Rebeck' seem to be at a discount with the morris dancers, and an old cracked violin is the substitute employed instead ... '

14. The same correspondent reported in 1860 that ' . . The old 'tabor and pipe' and the 'Rebeck' seem to be at a discount with the morris dancers, and an old cracked violin is the substitute employed instead ... ' ![]() 15. Again, in 1863:

15. Again, in 1863:

... The Morris dancers ... still obstinately persist in employing a squeaking 'fiddle', instead of the more legitimate tabor and pipe, notwithstanding what has been said respecting it, and which considerably marred the effect of the whole ...This was not the final victory of the fiddle over the pipe and drum; Wells recalled in 1914 that ' ... not more than 60 years ago there were several good pipe and dub players. I can remember 3 different players myself not more than 40 years ago [i.e., in the 1870s]'16

Ultimately the problem was to find adequate musicians of any instrumental persuasion. In 1914 Wells noted that his grandfather, George Wells (1822-1885), formerly the leader of the Bampton side,

" ... never had no trouble to get the dancers but the trouble was sixty, seventy years ago to get the piper or the fiddler - the musician. Sometimes they had a very great difficulty in getting one, they've had one from Buckland, they've had one from Field Town ... and they've had to go out here to Fairford and Broadwell and out that way to get a piper ...Any tradition constantly undergoes adaptation, alteration and reinterpretation. This may be subtle, or on occasion, as illustrated by the changeover from pipe and drum to fiddle, overt. In Bampton the change of instrument urged a modification of the dance style. The fiddle did not provide the same crisp, measured and even rhythm produced by the pipe and drum. Wells observed that:19

" ... The music ... is [at the date of writing] most of it too quick, and the old graceful movements are slurred to keep pace with it ... They used to play much slower on the whittle and dub, but it was very beautiful and you could grasp every movement ..."Some may have viewed the transition as a negative feature, but in the dancers' perception the reverse may have been the case. In purely physical terms the rhythmic pace at which it is comfortable to play the fiddle is also more comfortable for dancing. The slower pace of the dance lamented by Wells perhaps made for aesthetically more spectacular viewing but would have been uncomfortable to all but the fittest and most able dancers. A playing speed of, for example, crotchet=60, requires the dancers to make flamboyant leaps into the air to remain true to the rhythm .20

We cannot, however, be certain that the pipe was often, if ever, played at so slow a speed. At Brackley in Northamptonshire, where the dance set was accompanied by successive pipe and tabor players until near the end of the nineteenth century, the dancers insisted on crotchet=100 as a correct speed.

We cannot, however, be certain that the pipe was often, if ever, played at so slow a speed. At Brackley in Northamptonshire, where the dance set was accompanied by successive pipe and tabor players until near the end of the nineteenth century, the dancers insisted on crotchet=100 as a correct speed.

Exactly what style of fiddle playing was the reporter complaining about when he described it as 'squeaking'? Obviously we possess no aural evidence from the nineteenth century, but field recordings made during the present century offer examples which, in rhythm and playing style, at least, must be very similar. Wells was recorded on a number of occasions during the 1930s and '40s. ![]() 22 His playing is rhythmically rather smooth, and most often has a purity of tone which is at odds with many other of the recorded traditional musicians who played for morris dancing at other locations. Sam Bennett of Ilmington, John Robbins of Bidford (both in Warwickshire), Charles (or George) Baldwin of Clifford's Mesne (Gloucestershire), and his son Stephen, who played for the Bromsberrow Heath (Worcestershire) Morris Dancers, were perhaps more typical

22 His playing is rhythmically rather smooth, and most often has a purity of tone which is at odds with many other of the recorded traditional musicians who played for morris dancing at other locations. Sam Bennett of Ilmington, John Robbins of Bidford (both in Warwickshire), Charles (or George) Baldwin of Clifford's Mesne (Gloucestershire), and his son Stephen, who played for the Bromsberrow Heath (Worcestershire) Morris Dancers, were perhaps more typical ![]() 23. These men, together with Bertie Clarke, who played for the Bampton side on and off between 1926 and 1958, had a style which is highly, almost fiercely, rhythmic at the expense of purity of intonation.

23. These men, together with Bertie Clarke, who played for the Bampton side on and off between 1926 and 1958, had a style which is highly, almost fiercely, rhythmic at the expense of purity of intonation. ![]() 24

24

Clarke's playing, for example, has been described ' ... almost as a succession of grunts and squeals welded together by a wealth of slurs and blue notes into a wildly rhythmic pattern, now with, and now against the beat of the dance ...' ![]() 25. Similar comments might be applied to a greater or lesser extent to the other musicians mentioned above. There would, of course, always have been considerable variation in the degree of individual competence. Some, like Wells, would have been more able players whose recordings were performed using a fiddle with reasonable tonal qualities. Others may have possessed instruments which were less than perfect and adversely affected their intonation. But the style of playing - techniques of fingering and bowing, simultaneous drawing of the bow across the string below the one being fingered, rhythmic accentuation, and so on - would have been similar throughout the area.

25. Similar comments might be applied to a greater or lesser extent to the other musicians mentioned above. There would, of course, always have been considerable variation in the degree of individual competence. Some, like Wells, would have been more able players whose recordings were performed using a fiddle with reasonable tonal qualities. Others may have possessed instruments which were less than perfect and adversely affected their intonation. But the style of playing - techniques of fingering and bowing, simultaneous drawing of the bow across the string below the one being fingered, rhythmic accentuation, and so on - would have been similar throughout the area.

It must be borne in mind that such recordings as do exist were made when the performers were long past their prime, and using factory made violins and bows, and mass-produced violin strings. There are no extant recordings of players in their youthful prime, with fingers supple and strong. Nor are there any recordings of the home-made instruments, bows and strings such as we find in accounts of nineteenth century playing. Wells, for example, learned to play on a self-produced instrument concocted from a rifle stock and an old corned beef tin. ![]() 26 An account of morris dancing in, or near to, Rissington, Gloucestershire, during the late nineteenth century refers to accompaniment by a musician using a home-made fiddle which consisted of

26 An account of morris dancing in, or near to, Rissington, Gloucestershire, during the late nineteenth century refers to accompaniment by a musician using a home-made fiddle which consisted of

" ... two tins fixed at either end on a strip of wood with a piece of whipcord stretched across from one tin to the other. A bow was used but he [the informant] cannot remember how the notes were made. He says that "there wasn't much of a tune about it, it just kept the dancers going"It is clear that the fiddler (or fiddlers) who was derided in the newspaper accounts of Bampton performances quoted above was using an instrument of the mass-produced type; had it been home-made the reporter would have made much of the fact as further justification of his indignation.27

It appears that knowledge of the dance steps and movements and the ability to play the fiddle to accommodate and facilitate the execution of those features was considered more important by the participants themselves than the type of instrument used. Wells remembered his grandfather, George Wells, praising the playing of Richard Ford: ' ... Dick Ford was the best fiddler we ever had. He was born and bred here [in Bampton] . He knew every movement in every dance. My grampy said he would make them do it right ... ' ![]() 28. In fact, it appears that the musician was often the bearer not only of tunes but also of dance features, and often taught the steps and figures to the dancers:

28. In fact, it appears that the musician was often the bearer not only of tunes but also of dance features, and often taught the steps and figures to the dancers:

" ... My grampy used to say that he liked to get men [i.e., musicians] from Fieldtown, Finstock and Filkins to come in because they always brought a new tune or two with them. That's how we got new tunes. They explained the tunes and put them through it [i.e., explained to the dancers the movements dictated by the tune]. Then the local men would pick them up and play them ..."Given the number of musicians who moved in and out of the Bampton performance arena during the second half of the nineteenth century, the tradition could scarcely have remained static. Many musicians had been forgotten by name by the time Wells came to compile his manuscript history around 1913, but he listed the following men as having played the fiddle to accompany the Bampton set:29

Robert Batts - Bampton about 1858Brief biographical details of some of these musicians illuminate additional aspects of the performance context. Robert Batts was born in the hamlet of Lew, two miles to the north-east of Bampton in 1796. He married a woman named Beechey, who was perhaps a daughter or other relative of the pipe and tabor player, 'poor old Master Beechey, of Lew', who had played at Bampton early in the century. For such a tiny settlement, Lew was a veritable hotbed of morris musicians during the first half of the century. In addition to the two men named above, John Dix (1787-1855), a piper and fiddler who played for the morris dancing at Field Assarts in Wychwood Forest, and James Provis (or Probets, born 1836), another player at Bampton, were also born there.

Tommy Louis out of Berkshire from 1862 'til 1870

Jim Provis - Bampton

old fiddler Butler - Bampton 1876

Dick Butler his son about 1880

'til I [Wells] took his place in 189930

It is not difficult to imagine the transmission of both playing technique and the repertory of tunes and dances carried by older musicians within a small, closeknit community.

It is not difficult to imagine the transmission of both playing technique and the repertory of tunes and dances carried by older musicians within a small, closeknit community.

Tommy Lewis was a gypsy fiddle player who often, at least in later life, camped at nearby Standlake; as is often the case with travellers, I have been unable to trace any details of his birth or death. He is, however, also recorded as playing for the Abingdon (Berkshire) Morris Dancers, just prior to the First World War. Edward 'Deedlum' Butler, so nicknamed for his habit of 'diddling' the tune while playing (as did William Wells at a later date), was born in Burford about 1813, and later lived at Asthall, where his son Richard was born in 1854. The older Butler had a dancing booth which he used to take round and erect at fairs as far away as Blackwell in Warwickshire. There was no charge for admission but a man paid a small sum (perhaps a penny) for each dance in which he and a partner joined. Country dances would, at that date, last for a considerable length of time, often until the dancers got too tired to continue. Another of Butler's sons, William, would act as lead dancer, demonstrating how the figures were constructed and performed (perhaps after the manner of a modern-day barn dance caller), and then accompany his father on tambourine for the duration of the dance. It may well have been this father and son combination who provided the fiddle and tambourine accompaniment to the Bampton dance performance in 1877 noted above. ![]() 32

32

The story of how Richard Butler ceased his association with the Bampton Morris Dancers has been frequency told. ![]() 33 A variety of reasons have been cited as the main cause of the final rift. Most often the story is that either Butler got too drunk on the beer and cider given the men on their dancing route, because unlike the dancers he had no opportunity to sweat it out, or that he was dissatisfied with his share of the money collected during performance. The stories do, however, generally agree that one Whit Monday (1899, according to Wells), Butler caught the neck of his fiddle in a drainpipe and it broke off. He was apparently relieved about this and used the opportunity to cease his involvement. Wells, who had acted as fool for the side since 1887, ran home to get his fiddle and they carried on dancing for the rest of the day.

33 A variety of reasons have been cited as the main cause of the final rift. Most often the story is that either Butler got too drunk on the beer and cider given the men on their dancing route, because unlike the dancers he had no opportunity to sweat it out, or that he was dissatisfied with his share of the money collected during performance. The stories do, however, generally agree that one Whit Monday (1899, according to Wells), Butler caught the neck of his fiddle in a drainpipe and it broke off. He was apparently relieved about this and used the opportunity to cease his involvement. Wells, who had acted as fool for the side since 1887, ran home to get his fiddle and they carried on dancing for the rest of the day. ![]() 34

34

Wells continued to play for the dancing until 1925, receiving extensive patronage from the urban folk-dance revival based in London and Oxford. He was, according to his own reports, increasingly perturbed at the amount of alcohol consumed by the dancers, which often affected their performance. Additionally, there was conflict within the team as to who was the actual leader of the morris: Wells believed that, by virtue of a family connection extending back over a century, he ought to be leader, while the dancers, who at that date were mostly drawn from or related to the Tanner family, which had a similarly extensive connection, thought it ought to be one of them. In a confrontation which I have examined in detail elsewhere, Wells ceased his association as musician, thus temporarily ending a forty-year run as participant in the side ![]() 35. In 1926 the Tanner team danced out on Whit Monday with Bertie Clarke and Sam Bennett, both already mentioned, playing fiddles, either singly or in tandem, the former reading from musical notation on a music stand. The following year, Wells reappeared with another set of younger dancers, and it was this side which continued dancing throughout the second war and beyond. Meanwhile, the Tanner team sporadically performed, with Clarke playing, during the 1930s and again in 1941.

35. In 1926 the Tanner team danced out on Whit Monday with Bertie Clarke and Sam Bennett, both already mentioned, playing fiddles, either singly or in tandem, the former reading from musical notation on a music stand. The following year, Wells reappeared with another set of younger dancers, and it was this side which continued dancing throughout the second war and beyond. Meanwhile, the Tanner team sporadically performed, with Clarke playing, during the 1930s and again in 1941. ![]() 36

36

It is at this point that Arnold Woodley enters the narrative. ![]() 37 Arnold was born, the second of four children, on 14 November 1925. His older brother Frank performed as a dancer in the Tanner set for two years, 1931 and 1932. Their uncles, Jim and Arnold Buckingham, had been in the young set raised by Wells during 1926, but by 1930 were performing with the older, Tanner set. Although he remembers watching the older men practice as a youngster, and indeed would step into the set on occasion when one of the dancers needed a break, Arnold did not dance in the performing set until Whit Monday 1938, as a lad of thirteen.

37 Arnold was born, the second of four children, on 14 November 1925. His older brother Frank performed as a dancer in the Tanner set for two years, 1931 and 1932. Their uncles, Jim and Arnold Buckingham, had been in the young set raised by Wells during 1926, but by 1930 were performing with the older, Tanner set. Although he remembers watching the older men practice as a youngster, and indeed would step into the set on occasion when one of the dancers needed a break, Arnold did not dance in the performing set until Whit Monday 1938, as a lad of thirteen.  He was then much younger than the men preferred (this was probably related to the quantity of alcohol consumed during performance), but his cousin Charlie Buckingham, only three years older, was also dancing that year, and his uncle Jim told the other men that without Arnold they would be turning out with only five dancers. Arnold continued to dance on occasion until 1943, when he was stricken with rheumatoid arthritis.

He was then much younger than the men preferred (this was probably related to the quantity of alcohol consumed during performance), but his cousin Charlie Buckingham, only three years older, was also dancing that year, and his uncle Jim told the other men that without Arnold they would be turning out with only five dancers. Arnold continued to dance on occasion until 1943, when he was stricken with rheumatoid arthritis.

Following the war it became increasingly difficult to guarantee the services of a musician, especially for practices. William Wells had, by this date, become very deaf, which was affecting his playing, and was also practically blind, having to be led around by the arm. ![]() 38 He formally gave up his regular annual performances on Whit Monday, 1948. Arnold and Frank Woodley persuaded Bertie Clarke to become the regular musician once again, and Clarke played for the adult side every year between 1949 and his death in 1958. One contemporary observer claimed that the style of dancing was affected by the changeover from Wells to Clarke.

38 He formally gave up his regular annual performances on Whit Monday, 1948. Arnold and Frank Woodley persuaded Bertie Clarke to become the regular musician once again, and Clarke played for the adult side every year between 1949 and his death in 1958. One contemporary observer claimed that the style of dancing was affected by the changeover from Wells to Clarke. ![]() 39 Although the basic tunes, dance steps and personnel remained the same, Clarke's individualistic sense of the internal rhythms physically affected the kinetic manner in which the dancers performed. (It may always have been the case that a change in musician so affected the dancing.)

39 Although the basic tunes, dance steps and personnel remained the same, Clarke's individualistic sense of the internal rhythms physically affected the kinetic manner in which the dancers performed. (It may always have been the case that a change in musician so affected the dancing.)

The musician situation must have appeared somewhat precarious, because Arnold decided to learn to play the fiddle. He had two attempts at manufacturing his own one-string affairs, one made of wood, the other of tin, both with a matchbox for a bridge. He recalls taking one of them into the Jubilee pub and playing, which 'caused a riot'. He later bought a real fiddle for ten shillings, and, naturally enough, his first inclination was to play a morris tune, but that turned out to be 'disastrous'. Bertie Clarke showed him the finger positions for the tune used for The Nutting Girl jig and told him to practice scales every day. His diaries reveal that he first played for a morris dance practice on 14 March 1950.

During the late 1940s there had been some personality clashes within the side and Arnold left to form his own team of young boys, which first danced out on 10 June 1950, and continued in synchronous performance with the side of older men led by Francis Shergold until 1959. During this decade the two sides existed in apparent harmony, with Arnold doing the majority of teaching within the village, and some of the youngsters joining the older set as they got older and taller.

Peter Kennedy visited Bampton on Whit Monday 1955 and made recordings of the street dancing which were subsequently commercially issued. ![]() 40 These clearly reveal the differences in style between the musicians for the two sides.

40 These clearly reveal the differences in style between the musicians for the two sides.  Bertie Clarke plays the tunes very fast, Arnold at a much slower pace. Clarke, as previously noted, is rather raw in terms of technique; Arnold has a smoother style which is similar to that of William Wells before him.

Bertie Clarke plays the tunes very fast, Arnold at a much slower pace. Clarke, as previously noted, is rather raw in terms of technique; Arnold has a smoother style which is similar to that of William Wells before him.

Arnold has unfortunately been beset with frequent periods of illness over the years, which resulted in a period of relative inactivity between 1960 and 1970. At times during these years he would play for performances by the Shergold set, sometimes alone, sometimes alongside Reg Hall on melodeon. In 1971 he again fielded a team of his own and has continued to do so for the last twenty years.

His finest hour as a musician may have occurred at the Fiddlers' Convention held in Oxford in March 1986, at which he was one of the guests. Having practiced hard beforehand for an event that was clearly outside his usual playing context, he performed brilliantly and with tremendous confidence. (It must be stated, however, that Arnold believes his greatest personal triumph was a tour of the eastern seaboard of America during the early 1980s.) I suggest again that he is the finest traditional fiddler playing in the characteristic southern English style - long may he continue!

Keith Chandler

Article MT051

| Top of page | Articles | Home Page | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 3.10.02