And that was Raymond François, who was to write that book. (Ye Yaille Chere, Traditional Cajun Dance Music

And that was Raymond François, who was to write that book. (Ye Yaille Chere, Traditional Cajun Dance Music

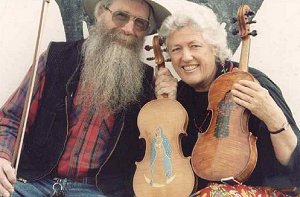

On this British tour, they appeared as a trio with the singer, fiddler and guitarist, Paul Rangell. Paul had been a founder member of the band over a quarter of a century ago. He was present throughout the interview and it was inevitable that he should join in when we came to the section of the interview that described the early days of the band.

On this British tour, they appeared as a trio with the singer, fiddler and guitarist, Paul Rangell. Paul had been a founder member of the band over a quarter of a century ago. He was present throughout the interview and it was inevitable that he should join in when we came to the section of the interview that described the early days of the band.

The interview was intended primarily for an article in the magazine Living Traditions and - as I write this - it is scheduled to appear in their next issue. Because of this, it will be seen that the first part of the interview concentrates on their early involvement in music and their time in Europe during the heyday of the folk scene. Ken and Jeanie were quite happy to talk about this, but they seemed to become much more animated when they were started talking about the traditional performers that they became involved with during their years in Louisiana and subsequently New Mexico. It was this enthusiasm on their part that convinced me that the full interview would be of interest to Musical Traditions readers.

There are quite a number of aspects of Ken and Jeanie's career that have not been covered by the interview, including the various manifestations that Bayou Seco takes for working in schools, festivals, dances etc, and Jeanie's involvement in The Delta Sisters and The Magnolia Sisters. However, it will be seen that there are other things that they wanted to talk about.

Ken and Jeanie seem to exemplify a very healthy attitude to traditional music and musicians. Rather like Reg Hall in Britain, they want to promote the traditional musicians that they work with and are quite happy to take a back seat when they are working with them.

On the day that I write this, I received a message to say that Bayou Seco will touring in Britain again in 2004; (April - 18 May 2004 and 16 July - Mid August 2004). I can only urge you to go and see them. Details of the tour as they emerge will be on their own website www.cantos.org/bayouseco and that of their British agent: www.accessallareas.info

J: I don't think that we did. We were all young - twenties - I had come over from Paris and I was playing with my partner, Sandy Darlington. We had done street singing for a year and a half in Paris. We thought, "There could be a better way to do this." We'd heard about what was happening in England. We made a little trip over to see what was going on and we were blown away by what we heard. We went back to Paris and saved real hard, street singing for three months. Enough money in the bank to keep us going here for a while. We didn't have any work and I don't think busking would have been any good for Americans there, though it was very lucrative in France. So we came over and within two weeks we started filling up our calendar. It was at that time when skiffle music was really popular and also people like the Watersons were just getting going, and were still singing the odd American song then. Lots of people were; the whole English folk song revival was just starting to take off. Ewan and Peggy had the Singers' Club. We were approved as real Americans singing American music, though we weren't from that tradition. I had grown up in New Jersey and Sandy was from Washington State. We were fascinated by traditional music and when we were in Paris we had gone to the archive at the American Centre and they had tons of recordings from the '30s and the '40s, like the stuff that's on the Harry Smith albums. We would just spend days there listening to all that stuff. So when we came over here we had a good repertoire, though living in New Jersey all I had was the Kingston Trio and the Weavers and what I'd heard on my radio. I could pick up WWVA in Wheeling, West Virginia at night and I would hear the Carter Family and things like that in my little room and I'd hear these voices that just spoke to me. They were just real people; they were not commercial music voices. When I was a kid we spent our summers at Martha's Vineyard before it became a posh place, and there were people like James Taylor and Bill Keith, the banjo player, Geoff Muldaur were our beach party friends. So I've always been into folk music, all my life.

Sandy and I lived here for almost three years. 1964-1967. We lived in Camden Town, just down the street from Bill Leader, so we got to know all the people that he was recording. He was like our best friend and the Watersons always stayed with us and we always stayed with them when we went up to Hull. So we just got right into the thick of it. And because we played traditional music, it was easy to get work in folk clubs and at festivals. We loved it. Bert Lloyd helped us to get a year's visa to do research at Cecil Sharp House. It meant that we were able to go into Cecil Sharp House and listen to the music that the Watersons couldn't get to listen to. It was a neat time to be here. It was so alive. There wasn't that much separation between the Beatles who were happening at that time and folk music. It was all equally important and exciting to everybody. Ken came over during the'70s and he went to lots of folk clubs then.

K: I grew up in an area that was mostly a lot of people from the south and south-west and a lot of Mexicans. This was in California. There was always traditional Hispanic music in the area. And there was a lot of traditional music in the Country Music Radio at the time and it was the performers that were the DJs. There wasn't the separation that there is today. There was nothing like a Top 40 Country Music. So you got to hear old singers on 78s that had been friends of the presenters. They would talk about them on the radio. And the parents of the Mexican kids that I played with. They played Mexican traditional music and had the Hispanic records. I was surrounded by that music. My father loved all sorts of music and he played the harmonica. He worked really hard; he didn't have time to play music. He had eight kids. Dad was born in Albuquerque. My grandparents were all from around New Mexico and Arizona. I started to learn to play harmonica, then I started to learn to play mandolin from an old Russian immigrant who was the father of a friend of mine. I got into the guitar and I taught myself some piano. I started going out to see musicians, bluegrass at the Ash Grove in L.A. They booked Bukka White, the first time Doc Watson was on tour he went there. It was a big influence on me seeing traditional musicians. I was never into the likes of Joan Baez and all that stuff, because I heard all these other people and there's a certain rawness and honesty that touched something in my own experience, because I was so close to other traditions, living where I did. There's something that you can hear. This is not just somebody looking at a book and playing. There's a feeling about traditional musicians, that comes from human beings' experience. I was very attracted to that. Our family was sort of lower, lower middle-class. My father had quite a class-consciousness. He identified very closely with the people where we lived and from that I've always thought of music as the expression of the people as part of a community.

When I got out of High School, I worked for a while for my dad and then I joined the army, I learned some more guitar. I went to Vietnam, came back and got involved very heavily with the anti-war movement. Very heavily, for a while things got bad, but I kept playing music. It kind of held me together. Around 1970, I took up the fiddle. In 1973, I went to Louisiana and met Marc Savoy, the Balfa Brothers, Dennis McGee. D L Menard, Lionel Leleux, and all those musicians from down there. Barry Jean Ancelet, the folklorist who has done a tremendous amount for Cajun music in Louisiana. I stayed in the town in a little hotel called the Evangeline in Eunice and I was walking down the street one day with my fiddle and a guy in a car pulls up and he says “Hey, what have you got in that case?” And I said, “That's a violin.” He says, “Oh! Well, get in the car and come on home. We are going to play some music!”  And that was Raymond François, who was to write that book. (Ye Yaille Chere, Traditional Cajun Dance Music

And that was Raymond François, who was to write that book. (Ye Yaille Chere, Traditional Cajun Dance Music

At the same time as playing with the Cajun musicians, I was starting to play Appalachian music and the Contra dance music in California. I got involved in that scene, and I got involved with a girl and she knew these people that she used to play with and they moved to Germany and so ... By the way, I'd learned to play the banjo too as I went along ... They asked her to come play fiddle with them in Germany, and I said, “I'll come along.” I had enough money for a one-way ticket and 70 bucks extra, so I went over there in 1975 and I was in the band immediately because both Agi Ban and I knew more about the music than the other people that were there. Agi is a very good musician. She still plays in the Bay area in San Francisco. So we played with the band there. It was called Hogwood and we played for a year and a half in Germany, all over the place six or seven days a week for most of the time. At first it was hard, playing bars, folk clubs, not so much the American bases, all for Germans. There were lots of Irish musicians playing there at the time, so we got to know Eddie and Finbar, and the guys in De Dannan. All those groups were over there all the time touring. Clannad. We got to hang around with those kinda guys. Roger Sutcliffe from Bradford was over there a lot. Wizz Jones, Colin (Wilkie) & Shirley (Hart). It was pretty vibrant over there.

Then I went back to the States and just before I left the States, I'd started to take fiddle lessons from Earl Collins, me and a friend of mine, and we'd hang out with other musicians there. When I got back, that's what I started doing full-time. I'd made enough money in Germany just to spend a year travelling around, meeting and recording people in Quebec and all over. I hitch-hiked in every State. I was all over Appalachia. It was a good experience and then I went back down to Louisiana in January '78 and met Jeanie there. We had kinda met before, but it's an odd story. I don't want to get into that. We really met in Louisiana and Jeanie had been there for about a month.

J: I was at a crossroads in my life and I didn't know what I was going to do. I thought, “Well, if I go to Louisiana, maybe I'll meet someone who likes what I like.” I'd been split up with Sandy for five years or so. Our daughter was with him right then, and I had some time on my own, and I thought, “Well, I like Cajun music and I speak French, maybe I'll go down there” and Marc Savoy had been really nice to me and said, “You like this music. Come on down, you can stay with us for a while until you get on your feet,” So I did, but I hadn't been able to find a job because I was an outsider and I'd been looking for just any job, because at that time you couldn't make a living playing music at all. It's hard, it still is, so I was helping out in the Savoy Music Store doing whatever, and Ken came in and we felt like we'd already known one another for many years by the time that we met. Lots of mutual friends and experiences. Living in Europe, busking, and so on. And Ken said, “Well, how are you fixed for money right now?” and I said, “Pretty bad! I've applied for jobs and they just won't take me.” The Jantzen Sewing Factory. They thought I was down there to organise a union, because I was a Yankee.

K: That's what I would have been there to do, if it had been me.

J: Well, I finally did get a job there, the third time I applied. But they told me I was overqualified for the job. “We are not hiring you - you'd be bored.” I said, “I need something. I want to stay here.  I want to make a living.” So I finally did get the job. But within a few days of knowing one another, Ken and I hitch-hiked to New Orleans and did some busking and did very well. And we just got along right from the start, just like that. We ended up staying in Louisiana for a few years.

I want to make a living.” So I finally did get the job. But within a few days of knowing one another, Ken and I hitch-hiked to New Orleans and did some busking and did very well. And we just got along right from the start, just like that. We ended up staying in Louisiana for a few years.

K: We played with Beausoleil when it was sort of beginning, for a while and then we played with Maurice Barzas and he played at Snooks Lounge in Ville Platte.

J: He wasn't a famous Cajun musician. He wasn't even recorded or only a tiny bit, but he was just a wonderful musician, plays accordion, and his son, Vorance, who has since been recorded. He played drums and he was a great singer. And after Will Balfa got killed in that horrible accident, he needed another fiddle player. He asked me but I said that I wouldn't really feel comfortable. Women didn't really play instruments, even then. So I said, “Could Ken and I do it together and we'll share the money?” It was 25 dollars a night..

K: They didn't want to ask two people because they didn't figure that it was enough money.

J: We did the job together and it was great fun. We had to buy our own amp; everybody had their own amp, no band sound system - set up your own and play. So that's where we really learned a lot.

V: That seems so strange that even in the 1970s women would not play in bands. It would not have been the same here. There were plenty of women that I can think of playing in folk dance bands in the 1970s.

J: There was an occasional one played drums. One gig we played with Maurice, it was every Saturday, I guess. You played from 8.30 until 1 am and there were no breaks. If you had to use the bathroom, you just walked off and then came back. They played on without you. And this guy was really staring at me one night and he said, “Are you really playing that fiddle?” This was in French and I said, “Oh no! I'm not really playing it, the tape recorder inside it is playing it for me.” And turned to his friends and said, “You see, I told you so!” The women would sing ballads. When we were there we would meet quite a few of them who did that, but it wasn't considered lady-like, appropriate, for a woman to sit in a bar and play.

V : But even with younger musicians. Do you know the fiddler, Neti Vaandrager?

J & K: Yes, we know her.

V: She plays in a Cajun band out there when they are at home and she seemed to indicate to me that she prefers it when Bart Ramsey, her partner, can come with her to play with his keyboard.

K: It is hard.

J: It is just starting to change.

K: Well, it hasn't if Neti is still having problems. We haven't seen Neti for a couple of years.

J: She lives there now?

V: She is based in New Orleans for part of the year and part of the years she is in Europe.

K: There was only one Cajun band in New Orleans when we lived there and it wasn't a very good one. It's only since Cajun music has become a lot more popular. The centre of Cajun music was always in the country, around Eunice. Even Lafayette wasn't a big Cajun centre at that time. In the clubs in and around Lafayette, what you get is that dance hall kind of playing. We were lucky enough to be there and to know older people and to hear them play and to play with them. When we met Maurice, he had been playing at this same club for 35 years, every week and it was drums, guitar, fiddle and accordion. It was great because he was playing an older kind of style. We searched out the older musicians because we liked the style better.  It was a dance gig but it wasn't the modern dance hall Cajun style. That isn't a style that I really feel that comfortable with.

It was a dance gig but it wasn't the modern dance hall Cajun style. That isn't a style that I really feel that comfortable with.

J: It doesn't have that much depth. It is meant for people to dance to, fine; whereas the older styles, for one thing if you go back and listen to someone like Dennis McGee, Canray Fontenot, Wade Frugé and the like, sometimes you couldn't even tell what colour they were from their playing, the styles were so similar, going back to the '30s and back. Dennis McGee and Amedé Ardoin recorded together as far back as 1928, black and white. In some ways with the music there wasn't so much racism ...

K: (doubtfully) Well ...

J: Well, there was, but it was kind of underground and the black musicians were called 'Free men of colour'.

K: When we got there Revon Reed had started his show in Mamou on Saturday mornings with live Cajun musicians. At that time there wasn't a lot of revivalist musicians coming from other places. They really welcomed other musicians coming in so Cajuns could hear musicians who came to the area, like us playing our music. But they stopped that when so many people started coming from outside the area to play. Everyone in the world wanted to come and play on the show. We played on it quite often and Revon would say, “Bring your friends over, because we want to hear them. We want to hear you playing our music, but we want to hear you playing your own music.” All done live 9-12 on a Saturday morning. Broadcast from a bar, people danced and people were drinking.

J: Towards the end of out time there, Dewey Balfa got us involved in taking musicians into schools. So we took Dennis and Canray and Raymond Francois and some other people, Louis Spell. They played for the kids, just to show them their own culture. Talk a little bit about it. Make them feel proud of it. It was English in the schools but French was starting to come back in.  For a long time they had been punished for speaking French at school. Finally it all came back around and they were importing French teachers from France and Quebec to teach in the schools, but, of course, they spoke a different French and that caused a lot of trouble, because the Cajuns were made to feel inferior with their style of French which was just an old style of French. It was slangy and it had English words thrown in. if there was a word and they didn't know what it was in French. No-one told them that an 'aeroplane' had to be an 'avion'. So it was 'airplane'.

For a long time they had been punished for speaking French at school. Finally it all came back around and they were importing French teachers from France and Quebec to teach in the schools, but, of course, they spoke a different French and that caused a lot of trouble, because the Cajuns were made to feel inferior with their style of French which was just an old style of French. It was slangy and it had English words thrown in. if there was a word and they didn't know what it was in French. No-one told them that an 'aeroplane' had to be an 'avion'. So it was 'airplane'.

K: After a while the French people who had been brought in would be critical. They thought it was funny, the way they spoke French, the people from outside, but after a while, they realised that this was a sort of cultural imperialism. Then they started teaching it with more acceptance of the way people already spoke French.

J: The Cajun culture is a lot more than just French. The African influence is very strong, British Isles. Take a name like 'Balfa'; that comes from 'Balfour'. And then the local Indian people, the Coushatta and the Spanish were there; it's in the names. People pigeon-hole it as French-African, but it's a lot more than that. We found two communities where they still spoke German. Church was in German, business was done in French and dealings with the outside world were in English, but they spoke German at home.

K: The time that I was there in the early '70s, if you were young and you played Cajun music you were considered a kind of a geek. And the things that people were saying about Robert Jardell. He was a great Cajun accordion player. But people were just saying, “Oh! You Know, he's kinda' weird.” You're kind of out of it. By the late '70s, it was changing. People were really starting to get interested in it again. That was the good thing. That's what has kept Cajun music alive. It has to change, it can't stay the same. It must have it's roots in its community ... which brings us to New Mexico.

J: I was really sick. I have asthma and finally after multiple cases of bronchitis and pneumonia and whatever, the doctor finally said to me, “You have got two choices; you can either leave here on your own feet or in a box.” That's what he said. I said, “Oh! I'll take the feet.” I told him that I had once lived in New Mexico for about a year and a half in the early '70s about the time when Ken was doing all his anti-Vietnam stuff. That was when my marriage broke up. The doctor said, “Why don't you go back there. A lot of Cajuns who have your problem have gone to New Mexico, including Revon Reed." So we did. Ken said, “Well, I'm not really ready to leave here.” And I said, “Well, you can stay.” We weren't married at that stage.

K: I loved it there.

J: Yes, he did. I did too. I loved the people and the culture. The people were so warm and wonderful to us.

V: And you had made a mark, musically.

J: We loved it, but we just had to leave.

K: It was life or death.

J: So we loaded up our truck ...

K: Put the mattress on top. It was just like the Great Western Migration.

J: Just everything, oozing out of the side of it. I wish we had a photo of that. God, That was amazing. We drove all the way across Texas and we ended up in Santa Fe, of all places. Because when I'd lived in New Mexico, it was not far from Santa Fe. It was still a wonderful place. It was a place of culture, kinda rough and interesting. By the time we got out there in 1980, things had changed drastically. But meanwhile we had put our money down to rent a place for a year, next to a friend. So we were kinda stuck there. So we endured a year and a half in Santa Fe, which by that time had become what we called 'Fanta-Say'. We were not very happy there, but we made lots of friends in Albuquerque. For instance, Paul Rangell.  We were always beating the trail to Albuquerque, an hour south to play the gigs and make money. In the end we moved down there and we were happy there. Then six years ago we moved to Silver City, to live in a smaller community, but I still feel that Albuquerque is very much a home. We have so many friends and we go there often.

We were always beating the trail to Albuquerque, an hour south to play the gigs and make money. In the end we moved down there and we were happy there. Then six years ago we moved to Silver City, to live in a smaller community, but I still feel that Albuquerque is very much a home. We have so many friends and we go there often.

K: I worked there, construction work. I did some landscaping. I did a lot of regular jobs, especially when we were raising Nellie, our daughter, so that we had a steady income. We weren't on the road playing music all the time, though we did do a lot of artist-in-residence stuff in schools and started meeting musicians that way. When we were in Santa Fe we met a lady, Bonnie Apodaca. She saw us playing and she said, “Can you play San Antonio Rose?” and we said, “Yea”. She said, “Good! Well, maybe you can learn my music.” She was at that time about sixty-something and her grandfather had had a dance hall, so she knew all the old Spanish colonial dances. And she had a little dance group. She worked in the cafeteria in the schools and after school, she would teach kids how to do this stuff. So she had a little position in the community. She said, ”Well, there is nobody does these dances any more, very much.” So we went along and she had some recordings that were not real good of music that she used and she gave us some names. One guy called Alfredo Vigil and we went to visit him ...

J: I remember that so well, so clearly.

K: He lived in Chimayo, New Mexico. We visited him and we started learning tunes from him and from other musicians that we heard, so that we could play for her dances, playing these old Spanish colonial tunes.

J: There were about ten tunes that we just had to learn. How to play La Cuna that's the cradle dance, La Escoba and the first dance of the night which is called La Cadena, the chain waltz. Then there would be a polka and a waltz.

K: Then there would be the quadrilles, which, of course, were in jig-time. And then La Cuna that changes. It starts of in 2/4 and then changes into 4/4. It starts of with a schottische and then it moves into a little polka, in 4. There's actually not many musicians that know how to play for that.

J: There's some tunes that are very similar to the ones we're hearing over here. A polka that you were playing last night (one from the Welch manuscripts) is very similar to one we've used for La Cuna and some that Katie (Howson) has played. Then Ken has played a tune and Katie said that it was very similar to one that she plays. Obviously, all the music that you hear in New Mexico, even more than Louisiana, has come from a really wide variety of European sources. Some people would make you believe that it is Mexican music that has come up the trail. Well, some of it is, surely, but there were so many people that came to New Mexico, like the Italian stoneworkers and the miners that came from Central Europe, many from Poland and the Ukraine. If you go to the cemeteries around the mining areas, you will see where all the names are from. And you hear music that is Italian, for sure.

K: I think that the music was more influenced by people coming in than the dances were. The dances started to die out because it was so isolated in Northern New Mexico. They were group dances originally, because in the 1600s, when New Mexico started, there weren't any couple dances, so people danced in groups, of one sort or another. As time went on, some couple dances came in. Well, we are just surmising, because there are not a lot of written records about this. Sometimes to keep the dances going they would stick a bit of a couple dance in and put it to the 'B' part of a group dance. They have quite a number of dances where there's a group dance for the 'A' and then a couple movement for the 'B'.

J: Like the Chain Waltz that we do. Circle left, circle right then into the middle and out and then you dance with your partner and then you circle up in another group.

V: There are elements of British and French dances in what I've seen of your dances.

K: Exactly. Well, the French had a big influence in New Mexico. As time went on that was the dances that they did. And then they would add things or subtract things and pick up tunes and then make up some dances like La Indita.

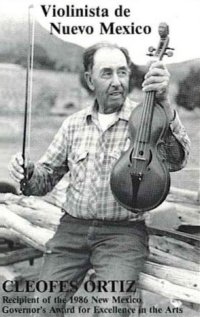

Then when recorded music came in, in the USA in the 1920s and 1930s, Polish highlander music, Norteño music, Black music, Cajun music - and started selling the records in furniture stores. Well, in New Mexico, they didn't have furniture stores; people made their own furniture. They didn't have electricity in many places until around 1940 and that would be from old batteries, so they just got to hear the radio a little bit then. They were very isolated with their own music, and nobody was recording that music, because there was no market for it and the record companies weren't interested. It was so isolated. Most of the folklorists didn't speak Spanish and so they weren't going up to this area, collecting. Ruben Cobos collected some. (see http://www.cc.colorado.edu/Library/SpecialCollections/Cobos.html) So because when they did get 78s, because there were no radios, the records were all of Norteño, Tex-Mex and Country music. So what happened was that New Mexican music became the music of those 78s and it's only the old people who remembered and played the older dances and music. This was what was happening when we got there. There were still a lot of older people along the Rio Grande, which was more populous. We would meet people in their 70s who remembered the old music. If we got up in the mountains, between Las Vegas, New Mexico and Santa Fe, you would find other communities where it survived. In fact, we played fairly often at a dance hall in Pecos, up on the river, in the mountains, where old people would come to the dances. We didn't have to say this is La Cuna and teach it, we would just play it and they would get up and dance. I think it was probably the last place.  Because when we went there with Cleofes and almost all the old people who used to come to that dance, were in the Senior Center and they didn't go out at night. We'd go and play at the Senior Center.

Because when we went there with Cleofes and almost all the old people who used to come to that dance, were in the Senior Center and they didn't go out at night. We'd go and play at the Senior Center.

J: But the two major people that we did meet there were Cleofes Ortiz and he lived in Bernal and we met him on my birthday. For me, it was like, the most magnificent birthday present I could have ever been given. We met him, I think it was 1984. He was at this festival in Las Vegas People's Fair. It was a kind of a hippy festival. And he was up there with Augustine Chavez. Playing this old stuff, and we were going, “Ah! He's the best one we've heard yet." We'd been searching around and they had all died, pretty much. Or they were very old and couldn't play very well. Fiddle players, that's what we were looking for. But Cleofes was just great. He has a big repertoire and he played really well, when you could get him to play without his amplifier, which we made him do. Pretty much, we weaned him off of that. He thought it sounded better with it. Finally, we got him to realise that it sounded better without it. And we started just gobbling up everything that he played. For about a year, we played with him a lot. It was about a two hour drive to his house, each way. By then we had moved to Albuquerque. We would go there as often as possible. And then he had gig with us once, where he had a stroke. He was helping us to unload the sound system and we told him not to, but he used to build stone houses and he was strong and, of course, he wanted to help us unload. He was stubborn! And he fell over in the parking lot and I was so distraught. There was someone in the bar who was an EMT person. He came out and said, “Take off his boots! Rub his hands and feet really hard and I'll get the oxygen.” And he ran to get the oxygen machine. So we were just doing that and I started whistling one of his tunes to him, just in desperation. It was called Rosita. Anyway, he'd been down about a minute ...

K: His heart had actually stopped.

J: He actually woke up before the oxygen came and he said, “¡Baile!, ¡Baile! We have to go and play for the dance!” So then they got him on the oxygen and they got him to the hospital and it was a long recovery period, but after about six months, he was able to play again. We kept encouraging him.

K: They gave him Coumadin and they didn't tell him that it would make him depressed, which it does. So he was really depressed. He hated where he lived, he hated music and then somebody told us about this and we told him and as soon as we told him, he went, “Oh! That's why I feel like this! Oh! I don't have to feel like that.” He just felt like he couldn't play; that he couldn't play like he did. We kept going out there every couple of weeks and we kept bugging him and bugging him to play. We'd make him play and he'd be really rough. But since we had learned a lot of his tunes, we were able to bring him back. And that's when he made these recordings, it was after his stroke.

(This is the cassette Violinista de Nuevo Mexico UBIK C3342 [see picture above] that they are describing.)

J: It's really great. It's about 25 tunes that he plays, they're played short, like two or three times through, with this guitar player, Augustine Chavez.  There's a few where I play, but it was just a document of what he did and he had a repertoire that was pristine, because he was born in 1910 and he quit playing ...

There's a few where I play, but it was just a document of what he did and he had a repertoire that was pristine, because he was born in 1910 and he quit playing ...

K: He quit playing in the late '40s.

J: Well when he started having kids, he had nine kids, he couldn't keep up the music and support all those hungry mouths. And he was a farmer, he raised corn. He did all sorts of odd jobs and he built stone houses and whatever he could do. He had quit playing, and his repertoire had stopped with him. And he hadn't gotten the modern stuff that was coming on the radios. That hadn't entered his repertoire. So that was really fortunate.

K: What he did learn, entered through other musicians. Like the Limbo Rock.

J: But he didn't know what it was, he just played it. Then when we played it with him, do you remember, at Port Townsend that year?

K: And people started doing the Limbo Rock dance to it and he was like, “What are they doing?”

J: "¿Que Pasa? ¿Que Pasa?”

V: But a traditional musician like that would just listen to what's available. And I bet he adapted it to his own purposes.

J: He did, he did. Yes, that's just what he did.

(Some discussion and examples of how English traditional musicians would take pop tunes and adapt them for their own purposes - Scan Tester's Cruising Down the River etc.)

J: All the fiddlers that we met including Alfredo, in New Mexico played The Isle of Capri but they all have their own way of doing it. It was great.

K: Cleofes didn't play The Isle of Capri.

J: No, he didn't, but a lot of the others did.

K: Over the Waves is one. Every fiddler that we came across played that one.

J: The other person that was certainly one of the best musicians that we did meet, shortly after meeting Cleo was this woman, Antonia Apodaca. And she is a firebomb of a wonderful musician. And her husband, Max, played the fiddle. She played diatonic accordion, 3 row and 2 row.

K: 2 row now.

J: And guitar. She played lead guitar and she was really great. And they'd lived up in Wyoming, even although they'd had been in New Mexico since they were kids. They'd gone up to Wyoming to pick beets. That was the big crop up there.

K: And then he got a job in the uranium mines.

J: And they raised their five kids in Wyoming. So their music changed with living there and being more countrified, more Country & Western. They'd take their polkas and they'd tilt them a little bit to the left or to the right to be a bit more Country and Westerny to appeal to the ranchers so they had lots of music and they finally moved back to New Mexico after all their kids were raised up. When we met them, it was one of the events that Cleofes was at and we became really good friends with her and her husband. And then shortly after that her husband died of a heart attack. So then we kind of took her under our wing after she went through her year of not playing. We started getting her out and took her to San Diego for the festival, to Port Townsend, to Washington to the Smithsonian. We took Cleofes also.

K: Plus playing other local gigs with them.

J: Just to get her on her feet again, and now she plays most of her gigs by herself. She has a little amp and ... She is amazing. She has a little tape recorder and she will have a tape of herself playing guitar on a polka. Then she has another tape recorder and she will play more guitar. I mean this is really low tech ... and then she will play accordion live. Or sometimes she just takes along the one tape of her playing the guitar. She sticks it on and plays accordion with it. I mean, that's so great. She is 80! She figured out how to do that.

K: She lives at 8,000 feet. There's a house and an outhouse. She was born in that house and her mother was born in that house.

J: She cooks on a wood stove. She does have electric, no running water, she pumps water. The bears come and she says that when the bears come, she plays the accordion and that keeps them away. There's a lot of bears because she lives way up in the wilds. A few years ago, a bear broke into a woman's house and mauled her. An older woman.

K: She was ninety something years old, yup!

J: They can be really dangerous. When there's a drought and they are not getting enough food and water. She says, “I'm not afraid of the bears; when they start coming, I just start playing my accordion and that chases them away." She's great. She's just a total original.

V: And what sort of music does she play these days?

J: Very traditional New Mexican.

K: Plus the songs she writes. She writes a lot of songs, sort of blues.

J: The one we played as an encore last night. (Estas Lindas Flores on American Fogies Vol.1, Rounder CD 0379)

K: She writes songs, tunes in the old style. Accordion and guitar. She plays a lot of the old pieces that she learned from her father and her uncles. They were all musicians, through the generations in that area. She plays a lot of old tunes and she sings a lot of old songs. But when she goes on a gig, she likes to sing a lot of her new songs.

J: She writes some songs in English as well. She wrote one called I Had A Dream and it's about on a winter's night, waking up in the middle of a snowstorm and hearing voices. And the voices were her husband and her parents telling her to continue to play and do the work she was doing, because it was really important to do that. But it's conveyed in such a beautiful way in the song. And the chorus is:

So I got my pencil,

Then I wrote this song.

The night of the blizzard,

The night of the storm.

And it just talks about that. She's amazing.

K: She is. And we are talking about real serious storms. They get eight feet of snow up there sometimes.

J: Paul - what do you want to say.

P: Well, Antonia Apoldaca has got really unusual musical skills and abilities, I think.

J: We would love to see her come over here.

P: Her accordion style is syncopated and it's kind of 'choppy', and she extends a lot of the lines for longer than they are supposed to go ...

J: Or they are shorter.

P: She takes liberties and she expects all those around here will just follow and get her line and if you don't, her attitude is ... Well, she doesn't accept it easily. She is pretty demanding.

V: Is that because of her style or because she is used to playing on her own?

K: I think it's a combination of both because it is an isolated area. People there - Cleofes would do the same thing - usually they are only ever used to playing with a couple of different people. And so they followed each other. It was also true in Louisiana, when we played with Maurice. He would start a tune; he was always trying to play something that we had never heard. So, he would play something that he had not played in thirty years.

J: He was always trying to stump us.

K: He would play the accordion, one time through, and then it was our break - on stage! And then when people would sing, they might sing longer, or shorter, or they might put chords in a different place. Everybody in the bands in Louisiana at that time always listened really carefully to what other people were doing. So you had the freedom to do whatever you wanted because they were always listening to you. And if you held the 'five' chord another measure, they just followed. Nobody went, “Aw! He didn't change at the right time." And so they listened real closely. So I think that is more common in traditional music for people to do that and others to accept it.

J: Well, when you have got a dance, whatever it is - contra dance, square dance - you are relying on eight measures or sixteen measures for the dance to work, but in these other forms, it doesn't matter at all. And when you get to the other sort of music, which is Arizona music, which we have really been involved with. Music from the Tohono O'odham people. Most of the native American peoples in Mexico play fiddles, but in the United States, not so much. Up in Canada - yes well all across Canada and some up in the northern part of the United States, but not so much with the Apache and so on. Not so much fiddle playing. There was one in Louisiana - one Coushatta Indian, Deo Langley, who played fiddle. But these guys played fiddle because the Jesuits came through and tried to make them be Catholics and gave them fiddles 200 years ago. They learned to play for the Mass. So they had fiddles, they heard other music, they learned it. My theory is that the native American people don't have a binary system. They don't separate things into 2,4,8, but their music is really free. It has no ... the amount of measures has no bearing on the music and certainly the dance does not dictate it. So therefore, it is really free and that's what I love about it.

K: Many of the melodies are borrowed and filtered and hybridised from European melodies and rhythms.

J: Well, mazurkas, polkas, waltzes.

K: It is the same forms.

J: Schottische, Two-steps. Quadrilles.

K: So there's that, but also some of their melodies are sometimes recognisable to some people like yourself who's played lots and lots of tunes for lots and lots of dances over the years. There's a glimmer of a phrase that you have heard before.

Or in this case with these native Americans, living not too far from the border, their music could have been filtered from accordion tunes from the radio in the 1930s, say.

J: But also they knew what was going on in Tucson which was the nearest town - Tucson and Phoenix - they would have heard other influences besides - whatever.

K: Irish music, Polish even ...

J: Even Appalachian, because many, many people from the Appalachian area moved west. And so there's old fiddlers from Oklahoma, there's one in New Mexico we knew, a cowboy fiddler who had a repertoire that was real Appalachian. Munroe Gilmore, he used to play tunes and they were not the Texas style of tune. They were from much further back east. And that's what he retained as his repertoire.

K: But an example of the Tohono O'odham repertoire that sticks out in my mind quickly is Caballito Blanco. It is a tune that Cleofes also plays. A very similar melody, that has relatives in Appalachian music. And Strawberry Roan written by Curly Fletcher; not a Tohono tune, but there are New Mexican versions.

P: With some verses sung in Spanish?

K: With every other line sung in Spanish. I've sung that here (in England)

P: But Caballito Blanco is a tune that has interesting shifts from major to minor. I don't know; some of the tunes that we have learned from the Tohono O'odham people seem to have elements of Eastern European music in them.

J: To me there's also a Swedish influence. I think it's Karl Lumholz myself. He did a lot of collecting all around Mexico and he played the fiddle.

V: How did the band Bayou Seco come about? What year did that happen?

P: There's different versions of how that happened! We were waiting in line to play at an event called ... We'd been playing together some, kind of informally; we maybe had played one or two jobs ... We were waiting in line to play at the Santa Fe fiddle and banjo contest. We were thinking of what to call ourselves to enter this contest. My memory is that I said, “Why don't we call ourselves Bayou Seco?” but Ken's memory is that he said it!

J: My memory is that Bonnie Apodaca, who taught us all the dances lived in a place called Arroyo Seco, so we followed on to think that Bayou Seco was an appropriate title ... But anyway, we were all there at the time. The name came and it stuck.

P: It was the name that was put down for that contest.

J: Yea and anyway, Emily his girlfriend at the time started playing triangle with us and washboard. She already played some banjo and then she learned guitar. We sort of became a four-piece band. But then they (Paul & Emily) moved to Santa Cruz in 1983 and we had only been a band for a year, but we had made a cassette. We had made the Cactus, Gumbo and Alligator Enchiladas cassette.

P: We'd travelled ...

J: We went up to Washington ...

P: ... to Canada, twice as I recall.

J: On the road - that was fun! Stopping at night and camping, cooking ...

P: We played Minneapolis, Winnipeg ...

J: But even after you (Paul) moved to California, we still did a lot of that travelling together.

P: And then you came out to play in California.

V: Playing the same sort of music that you are playing now?

K: Sort of. We didn't know as much of the Tohono music or the Spanish colonial stuff as we do now, but we did Cowboy songs - we've also always collected Cowboy stuff. The new CD has a song on it called The Crooked Trail to Holbrook and I was showing that to my great-uncle - Lomax's book, or maybe it was Thorpe's (it was the latter), and it has this song, The Crooked Trail to Holbrook and he said “Oh! I remember that. We used to do that song. And actually, I drove cattle on that trail a couple of times with my father.” And they had driven cattle on that trail. They had down there by Holbrook. My grandmother was born in Globe, Arizona. And the trail goes right through Globe. Some of the people in the song were from Globe. I thought, “Maybe I should learn this song.” I seen one version of it but it didn't have a melody written down. But she (grandmother) said also that people used any melody that came into their heads because mostly the songs just came as words written down. So there have been lots of versions of these songs with all sorts of different melodies. So I just sort of made a melody up for it and put it in there.

J: But I would say that our early repertoire, Bayou Seco, was at least a half Cajun, more than a half, because Cajun was the money maker. We were always interested in playing at parties ...

P: That was our first name, Bayou.

K: And we had just got there from Louisiana.

J: And then we started learning more of the Spanish stuff.

P: And we learned some of the repertoire of Lydia Mendoza. And also I remember that we also shared other interests, so if we wanted to put together some songs, we could put together some Carter Family songs ...

J: Which, of course, are fabulous.

P: That was the glue, the fundamental repertoire. When we first got together, I was pretty new to the fiddle. I was a fledgling fiddler and I played a lot of mandolin at the time.

K: We played a lot of square dance music because we had all played for dances.

P: Of necessity. That was the work. If we were playing a bar job, I'm sure that we would be playing more Hank Williams' songs.

J: Like tonight. We are playing in a bar in Bridport. It won't be a show like last night (at the Royal Oak in Lewes)

K: If it's a concert, out come some French ballads. If people want fiddle music, we can provide it.

J: I think what we have done as we have gotten older and can do more and more stuff from different sources, we have kinda honed it more into the cross-cultural Chilli Gumbo, that's the South-West, with bits of Appalachian thrown in, just because that is different from what anybody else does.

K: Also, a lot of the people were saying, “This is great, but none of our kids are learning this stuff. You've got to learn it and teach it to other people.” So that people continue to play this music. I've been playing for dances and sometimes they are dances that don't exist anywhere else any more. We go back and play on the reservations sometimes, for celebrations or for, well, funerals mostly,  because we play an old style that isn't played that much, but now some young people are starting to learn it from our cassette which is sold all over the reservation - which is rather odd.

because we play an old style that isn't played that much, but now some young people are starting to learn it from our cassette which is sold all over the reservation - which is rather odd.

J: We put together a cassette of the music that we learned from Elliott Johnson, an old Tohono O'odham fiddler. He had taught us so much music and he died way too soon, too young. He was in his sixties - he shouldn't have died yet - but he did. And he had taught us all these tunes that he had not recorded ever and nobody knew them. So we made this little cassette called Memories In Cababi just to document some of the tunes. And that sells out on the reservations.

K: That's mostly where it sells.

J: Right before we left, I called the company that deals with them and I said, “Do you need any more? We are going away for three months.” And he said, “No, I think I can manage until you get back.”

But we went into a trading store one day, on the reservation and we were looking at the CDs and cassettes and there was our Memories In Cababi - Bayou Seco - Well, it says 'Bayou Eclectico' because it was with lots of members of the Bayou Seco Family.

K: It doesn't have our picture on it.

J: And the lady said, “Do you like this music?” and Ken said “Yes, in fact that's our cassette, that's us.” And the lady said, “No. This is our music!”

P: Great! It's a great example of what they are speaking about now. One thing I'll never forget is the first time that we went out searching for these fiddlers that we met eventually, through this friend of ours who loaned us a cassette. It was at Easter time around, I suppose, 1989. Because my boy was a baby. Well, we went out there and, you know, it's pretty bleak and we drove out just the four of us and our baby.

J: Blond curly-haired baby.

P: Yes, he looked pretty amazing at the time. And I think that my wife might have been pregnant with number two. So here we are, a motley crew. We get out there and they are having an Easter feast. We walked right up and there's long tables and we said, “Well, we are looking for an Elliott Johnson, Lester Vavages.” You know, these fiddlers were not there.

J: They had been there earlier!

P: They had been there. We were invited to stay and dine with them, probably fifty or hundred people were dining with Jello and potato salad, beans and these beautiful, extraordinary tortillas that they make. So there they were, having their ceremonial dance in one corner of the courtyard. These guys would have their Levis rolled up to their knees, dancing barefoot ...

(At this point the phone rang and by one of those extraordinary consequences that life throws up, it was Neti Vaandrager, who we had been talking about earlier in our conversation. She was phoning from New Orleans. I had not been in contact with for over six months and Jeanie and Ken had not for at least 2 years. At that time we did not get the end of Paul's story. However, Ken was able to finish it for me later)

K: Picking up quarters with their teeth, dancing to these great 6/8 Yaqui Indian Pascola (Easter) tunes played by an old fiddler. They had deer rattles strung around their ankles and they would rattle in time to the music.

(By the time we finished the phone conversation, we came back to another subject - the current state of the Spanish influenced traditional music in New Mexico.)

K: In New Mexico, the traditional Spanish colonial music is, for all intents and purposes, almost gone or there are only a few people do it. When people think of New Mexican music now, they think of that Mexican Country sound. There's a particular sound to New Mexican popular music. It's got its own sound, but it's only very distantly related to the Spanish colonial music and the old ballads that they sung. There's one other old guy, about our age, who plays it, Cipriano Vigil from El Rito, NM. He is a singer and he writes some of his own songs. So there is not much dancing. There are some people who put together little dance troops and do some dancing. But we try to teach it as much as we can. But the attitude is one of not even knowing that this music and dancing existed. I think that in a few years people may become interested when they realise that it is gone or going. Maybe there will be a revival. It gets very little media exposure, because even the media doesn't know it exists. We've done some things on public TV and sometimes on the Spanish TV stations, there's a few things, but it's difficult. Basically, there's a lot of politics involved - us being Anglos. Not so much from the communities where the music was played. They don't care, but when you get into the cities, you get involved with cultural politics at the universities and within the Arts Folklore committees and the people who control the money - the funding. They have the idea that it's almost better for something to die than encourage someone who didn't grow up in one of the villages to get involved.

At one time, Cleofes Ortiz - we heard that he didn't qualify for arts funding because he had learned his music from his uncle and not from his father. There's a lot of bizarre politics in this. It's the same all over the world. The use of cultural power and all that. We decided at one time that it was too frustrating to deal with; let's just do what we do. We do get a very good response when we play in villages and little communities in Northern New Mexico, from the people there. There's none of these problems with that. The problem comes when you try to get funding.

J: We never bother to try to get funding any more, so therefore we funded it ourselves. We just went forward and met people and recorded them and we did put together one little cassette for the archive at the University of New Mexico called Ten Great New Mexican Fiddlers and we have given them to their families. These families didn't even have recordings of their old granddad. Stuff like that we have done ourselves. But we have stayed out of the whole political part of it.

K: Every time that we do, we get burned; but we might be able ... There is a guy who collected; a guy John Donald Robb who was the head of the music department starting in the 1950s or late 1940s at the University of New Mexico. We knew him; He died when he was like 98. He had collected all over the place. He wasn't really a folklorist, so he just collected, so it's not folklorically great stuff sometimes. But it was really fortunate that he did all that. We know people at the archive and we do songs that we have learned. They would have us put on something at the Spanish cultural centre; we will have to wait and see if that happens. It might have to be somewhere else because of the politics. But the people at the archive want it to happen, because nobody else is using the stuff that is in there; to get that music back out. It has never got back out to the people. It is real sad. A long time, we made tapes of the music from the archives. It was more open then. They've obviously clamped down on it since then. We'd send tapes to the local libraries and schools - the music of their areas and say, “Look, this was recorded here. Make this available", but usually it just disappeared. Somebody would hear it and say, “Oh! That's my uncle. I'll have that!”. There's got to be some way of getting that music back into the communities so that people know that the opportunity to start re-learning the tunes and to start doing the dances, because there are still some people who remember them.

J: So often, it's the outsiders, the people who have come from outside the culture and the community who see the value in a tradition; who will try to give it back; who will wake those people up and say, “Look at this! You didn't see any value in it because you were too close to it. But it's a monumental job.

Vic Smith - 25.11.03

Article MT131

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |