The second piece in this series, involving the Bedford printer, Merry, provided an account of the Sarah Dazley execution, indicated that a ballad had been issued and considered its potential place in the hierarchy of such material, but, of course, failed to expose the ballad itself. On the other hand, the Merry imprint, hitherto somewhat obscure, is, at least, providing us with more detail of the workings of the broadside ballad trade.

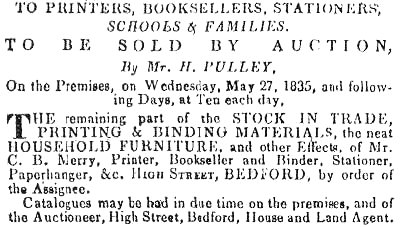

In the latter respect, then, apart from the information already given about the fortunes of the family and its dates of operation, it is also known that Clarke Barbour Merry was occupying some old granaries as a ‘dwelling house, shop and premises’ in High Street, Bedford in 1831.![]() 2 This may suggest a change of address from the ‘old-established’ office in Castle Street but, equally, there is no reason to suppose that Castle Street was abandoned. It could be that both premises were being used. Indeed, the expansion may connect with the next known occurrence when Merry sold his stock in 1835.

2 This may suggest a change of address from the ‘old-established’ office in Castle Street but, equally, there is no reason to suppose that Castle Street was abandoned. It could be that both premises were being used. Indeed, the expansion may connect with the next known occurrence when Merry sold his stock in 1835.

Had he over-reached himself? Printers, in general, would seem to have been subject to fluctuations in fortunes - the Exeter Flying Post recorded several sales of stock, several bankruptcies and several fires amongst printers during the nineteenth century.![]() 4 Nonetheless, there is some evidence to suggest that printers were able to begin printing again afterwards. Bond, of Plymouth, who was declared bankrupt in 1816, was again declared bankrupt in 1831 so, in between, he must have recommenced printing (or, perhaps more correctly, working).

4 Nonetheless, there is some evidence to suggest that printers were able to begin printing again afterwards. Bond, of Plymouth, who was declared bankrupt in 1816, was again declared bankrupt in 1831 so, in between, he must have recommenced printing (or, perhaps more correctly, working).![]() 5 And we do know that John Wilson of Bideford, after being declared bankrupt, re-emerged as a printer and that William Petuluna of Helston followed a similar course.

5 And we do know that John Wilson of Bideford, after being declared bankrupt, re-emerged as a printer and that William Petuluna of Helston followed a similar course.![]() 6 We should remember, too, that even the great Jemmy served six months in prison but that, as Hindley wrote, ’During Catnach’s incarceration his mother and sisters, aided by one of the Seven Dials bards, carried on the business, writing and printing off all the squibs and street ballads that were required’.

6 We should remember, too, that even the great Jemmy served six months in prison but that, as Hindley wrote, ’During Catnach’s incarceration his mother and sisters, aided by one of the Seven Dials bards, carried on the business, writing and printing off all the squibs and street ballads that were required’.![]() 7 As shown below, after his particular brand of - unknown - misfortune, Clarke Barber Merry seems to have been quickly on the scene again.

7 As shown below, after his particular brand of - unknown - misfortune, Clarke Barber Merry seems to have been quickly on the scene again.

Pursuant to this: during the same year as the sale of stock, 1835, a document entitled ‘State of the poll’ was issued by Clarke Barbour’s son, J. S. Merry. It is, for the moment, a matter of speculation as to whether Clarke Barber had simply put John Swepson, then aged 16, in nominal charge of family affairs in order to facilitate a rapid return to printing for Clarke Barbour himself.![]() 8 At any rate, records show that, in 1837, a poll book was issued under Clarke Barbour’s name. We have already seen that his name as printer appeared in Pigot’s 1839 directory of Bedford. The address there was given as High Street (and see the discussion of the role of Clarke Barbour’s daughter, Mary Anna, below).

8 At any rate, records show that, in 1837, a poll book was issued under Clarke Barbour’s name. We have already seen that his name as printer appeared in Pigot’s 1839 directory of Bedford. The address there was given as High Street (and see the discussion of the role of Clarke Barbour’s daughter, Mary Anna, below).![]() 9

9

In the 1841 census information was given that Clarke Barbour Merry was still in High Street as a printer along with son, William, and daughters, Sarah and Mary; but that the elder son, John, also described as ‘printer’ - perhaps partly as a result of his apparent temporary direction of the family firm, never mind any apprenticeship - could be found then living independently, as it were, in the house of William and Mary Waters, in Well Street (present day Midland Road), Bedford. In an interesting reversal, the 1851 census gave Clarke Barbour’s address as 186 Well Street, where, as a widower, he was living with his two daughters, Sarah and Mary Anna, both described as ‘Dressmakers’ (one of the meanest of female occupations at the time); and that of John as being in the High Street. Whatever had happened, Clarke Barbour Merry was not - officially, at any rate - involved in the trade from around that time. As indicated in the second piece in this series, he was not recorded as a printer in the 1851 census and in 1861 was entered as ‘Printer Retired’ with an address in Harper Green, living along with his daughter, Mary Anna (unmarried and with no occupation listed). He died in 1868, aged 81 - the address was given then as Harper Green, Parish of Holy Trinity, Bedford.

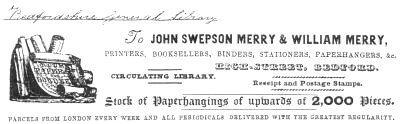

However, John Swepson Merry and William Merry were further recorded as having by 1842 set up in a fashion, like so many printers, and like their father, with at least one other business pursuit.

It does seem that many printers had more than one line of business. Pigot’s 1822 Commercial Directory for Wiltshire has Messrs. Brodie and Dowding operating in Salisbury as Booksellers, Printers, Stationers and publishers of the Salisbury and Wiltshire Journal; and William Bailey of Calne as Printer, Stationer (‘etc.’) as well as ‘sub-distributor of stamps’. In 1830 William Bailey had gone but a Thomas Bailey was listed as bookseller, stationer, printer and subdistributor…William Bird Brodie and Charles George Brodie were then operating as Booksellers, stationers and as ‘patent medicine vendors’.![]() 11 In Winchester, the firm of Jacob and Johnson was listed in Pigot’s 1828 Directory as booksellers, stationers and binders; in 1844 as booksellers, stationers and agents for the Family endowment assurance and the Hampshire, Sussex and Dorset fire assurance; and in both 1852 and 1854 as booksellers and stationers and agents for the second assurance mentioned directly above.

11 In Winchester, the firm of Jacob and Johnson was listed in Pigot’s 1828 Directory as booksellers, stationers and binders; in 1844 as booksellers, stationers and agents for the Family endowment assurance and the Hampshire, Sussex and Dorset fire assurance; and in both 1852 and 1854 as booksellers and stationers and agents for the second assurance mentioned directly above.![]() 12 Assurance and lottery agencies were, it seems, favourite additional jobs, as examples in Devon testify, this kind of multiple practice being in keeping with the volatile nature of the printing business itself as it has already been noticed.

12 Assurance and lottery agencies were, it seems, favourite additional jobs, as examples in Devon testify, this kind of multiple practice being in keeping with the volatile nature of the printing business itself as it has already been noticed.![]() 13

13

More to the point where ballad-printing is concerned, Andrew Brice, in Devon, ballad-printer, was, at a slightly earlier date, an agent for rat poison.![]() 14 Pitts himself issued stock from his ‘Toy and Marble Warehouse’ by which was probably meant battledore cards and primers for children; Fortey, inheriting Catnach’s stock, advertised ‘Children’s Books Song Books etc’.

14 Pitts himself issued stock from his ‘Toy and Marble Warehouse’ by which was probably meant battledore cards and primers for children; Fortey, inheriting Catnach’s stock, advertised ‘Children’s Books Song Books etc’.![]() 15 Samuel Harward, ballad-printer in Cheltenham, also sold patent medicines, was at one time a paving Commissioner in Cheltenham, and ran circulating libraries.

15 Samuel Harward, ballad-printer in Cheltenham, also sold patent medicines, was at one time a paving Commissioner in Cheltenham, and ran circulating libraries.![]() 16

16

So that the Merry family can be seen to conform in this respect although, in contrast, there is other evidence to the effect that a printer actually pursued his one trade. Willey of Cheltenham, for instance, seems to fall into this category. There is no record of additional trade pursuits in his case.![]() 17 It is as well, then, to look closely at individual printers.

17 It is as well, then, to look closely at individual printers.

In 1843, in Bedfordshire, came the Sarah Dazley affair, in which the brothers Merry were involved. Then, as noted in the previous Merry piece, William died in 1846. After this time, where the Merry family fortunes are concerned, comes a hiatus in enquiry. John Swepson Merry seems to have disappeared from Bedford records - but does turn up in the 1881 national census, unmarried, living in Surrey with two cousins, one from Clarke Barbour Merry’s birthplace, Moulton, Northamptonshire. He was listed in the census as ‘Printer, compositor’.![]() 18 Clearly, though, John Swepson’s association with the Merry imprint in Bedford is in doubt from the mid-century point on.

18 Clearly, though, John Swepson’s association with the Merry imprint in Bedford is in doubt from the mid-century point on.

We have already found![]() 19 that Mary Anna Merry’s initials were given on ballad-printings (see also full list below); but, in the 1861 census, she was recorded as aged 30, unmarried, and with no occupation, not even dressmaking. In 1866, she married (out of Harper Green) a John Wyant, Labourer, son of William Wyant, Grazier, at Holy Trinity, Bedford; and moved to John Wyants’ home at Riseley, just outside the county town.

19 that Mary Anna Merry’s initials were given on ballad-printings (see also full list below); but, in the 1861 census, she was recorded as aged 30, unmarried, and with no occupation, not even dressmaking. In 1866, she married (out of Harper Green) a John Wyant, Labourer, son of William Wyant, Grazier, at Holy Trinity, Bedford; and moved to John Wyants’ home at Riseley, just outside the county town.![]() 20 She was recorded in the 1871 census as residing with her husband and two children, a boy and a girl, from John Wyant’s previous marriage, in Riseley. It is possible that her fortunes then dipped. John Wyant died in 1876. His daughter had died just before him. The 1881 census shows that Mary was widowed and living in the same house as an Elizabeth Moore, back in Bedford. In fact, she was listed as being a servant.

20 She was recorded in the 1871 census as residing with her husband and two children, a boy and a girl, from John Wyant’s previous marriage, in Riseley. It is possible that her fortunes then dipped. John Wyant died in 1876. His daughter had died just before him. The 1881 census shows that Mary was widowed and living in the same house as an Elizabeth Moore, back in Bedford. In fact, she was listed as being a servant.![]() 21 On this evidence, we still cannot be at all sure when she was involved in the family firm or in what capacity - as part of the family pool of hands or in directing affairs.

21 On this evidence, we still cannot be at all sure when she was involved in the family firm or in what capacity - as part of the family pool of hands or in directing affairs.

There is one contemporary piece of information which may be relevant, even at a remove. According to one newspaper report, reprinted in the Bedfordshire Times, women, much to the disapproval of the writer, were being employed in printing offices. Arguments now familiar to us were advanced as to why women should be excluded:

Women are totally unfitted, physically and mentally, for the labour of the compositor - labour requiring the moist unremitting mental application, as well as great physical endurance, and to suppose that females are capable of this is a great mistake.Further still:

The system, too, has great moral disadvantages, from the association of the sexes in such a manner as would be required by this business.Finally:

The “proofs” of female compositors sufficiently prove how ill-adapted they are for the work. Whoever saw a lady’s letter “pointed” correctly, and how very rarely are a dozen consecutive words spelled correctly by the fair sex.If this be thought something of a tangential pursuit in this particular survey, it nonetheless could well have been applied to Mary Anna Merry, not simply because of the strictures themselves, but because of the fact that women in the printing industry had been brought to notice. Of course, this is not the only such evidence. As will be seen in a later piece, Elizabeth Williams ran the family firm in Portsea at one stage; and Ann Batchelar, Mary Birt and Anne Ryle all carried on businesses started by their families in London.22

For the present, Mary Anna’s part in the Merry family fortunes must be accounted something of a mystery, except that certain information is given on the ballad-sheets which help to identify something of her contribution under the Merry imprint.

A full list of known Merry pieces as ballads is given below:

Items 2 and 3, 6 and 7, 8 and 9, 14 and 15, 17 and 18, 21 and 22 were paired.![]() 24

24

The metrical pattern alone makes it quite clear that it was meant to be sung to the tune of God Save Our Gracious King:

Such material included pieces on the 1820, 1837 and 1854 borough elections (as indicated in the list given above) and involved The Marquess of Tavistock, Francis Russell (1788-1861; brother of John, 1792-1878, who himself became Prime Minister); Francis Pym; and John Osborn. Russell was MP for Bedford between 1812 and 1831and acceded to the title of 7th Duke of Bedford in 1839. Pym (1756-1853), a JP, lived at Hassells Hall, Sandy, a few miles distant to Bedford. Osborn (1773-1843) lived at Chicksands, a few miles to the south.

Election stuff, generally, may be counted as being particularly ephemeral and would not necessarily have meant that the Merry family took sides. There is evidence that the firm printed for more than one political party.![]() 27 However, the ballads issued in 1820 were clearly favourable to the Tory candidate, John Osborn, whose opponent was the Whig, Francis Pym. Though details are still missing on Osborn’s career, he certainly represented Bedford in 1818 (and previous to that date).

27 However, the ballads issued in 1820 were clearly favourable to the Tory candidate, John Osborn, whose opponent was the Whig, Francis Pym. Though details are still missing on Osborn’s career, he certainly represented Bedford in 1818 (and previous to that date).

During the 1820 elections one piece set out a potential stall:

Another piece placed the two candidates, Osborn and Pym, in opposition:

In 1826, A New Song (31 above) favoured the Tory candidate, Macqueen. This was Thomas Potter Macqueen (1791-1854) who represented Bedford as a Tory member of Parliament between 1826 and 1830. Macqueen’s main claim to fame lay in his involvement in matters Australian - encouraging emigration, setting up land ownership schemes in Australia… He it was who, in 1832, first mooted the idea of a national bank of Australasia.

We catch a glimpse, in the ballad, of what were supposed Tory priorities:

One more, produced in 1854 (37 above), referred to the success of Catholic emancipation, implying that the particular candidate, Trelawny, may have approved favourable legislation but was, nonetheless, a good Protestant still. ‘No Popery’ was, by then, ‘a worn-out cry’.![]() 29

29

Perhaps the details of such pieces need not concern us unduly except to note the apparent following of the fortunes of Tory candidates. Obviously, the firm would have been engaged in producing other material. In this respect, for instance, a notice can be found under the aegis of John Swepson Merry and William Merry indicating that a thousand circulars were made out (there are no details of customer or cause).![]() 30 Broadside balladry, then, was probably not the most prominent of the Merry firm’s concerns.

30 Broadside balladry, then, was probably not the most prominent of the Merry firm’s concerns.![]() 31

31

Finally, in the course of tracing the Merry contribution to ‘political literature’ it has emerged that there were other printers in Bedford who each issued election material - Hill, White and Webb, for instance. Hill and Son put songs on the occasion of the 1832 elections - ‘Whitbread and Crawley for Ever’; ‘The Bedford Union Society ALTOGETHER’; and ‘Britons looking forward in the Hope of Bright Days’ (by M Haydon).![]() 32 White printed an ‘Address from W H Whitbread trusting that he will again be elected as a member for Bedford’.

32 White printed an ‘Address from W H Whitbread trusting that he will again be elected as a member for Bedford’.![]() 33 Webb, in 1820, printed ‘An address from William Henry Whitbread soliciting the honour of being elected for a second time and promising constant attendance to the interests of Bedford’.

33 Webb, in 1820, printed ‘An address from William Henry Whitbread soliciting the honour of being elected for a second time and promising constant attendance to the interests of Bedford’.![]() 34 Yet it was Merry who had printed ‘An Address by William Henry Whitbread thanking the electorate for electing him’ in 1818.

34 Yet it was Merry who had printed ‘An Address by William Henry Whitbread thanking the electorate for electing him’ in 1818.![]() 35 To add to this particular mélange: Webb printed ‘Song in support of Whitbread and Russell to the tune of Hearts of Oak’ in 1830. Taking sides, as noted above, was not the first consideration of the printer; and candidates did not seem to mind which avenue they chose through which to publicise themselves.

35 To add to this particular mélange: Webb printed ‘Song in support of Whitbread and Russell to the tune of Hearts of Oak’ in 1830. Taking sides, as noted above, was not the first consideration of the printer; and candidates did not seem to mind which avenue they chose through which to publicise themselves.

Obviously, there is more still to be uncovered in this respect and the implications for a bigger study of such material are clear enough whether that material was ephemeral or not.![]() 36

36

Apart from ‘political’ pieces in the Merry stock there are then some which are the legacies of earlier times, a feature very much part of the staple stock of many nineteenth century broadside ballad printers: in this case the pieces are The Female Cabin Boy, The Silly Old Man and The Cunning Cobbler - Catnach and Harkness printed all three; Pitts, the first two; Hodges, The Cunning Cobbler and The Female Cabin Boy.![]() 37 The theme of The Cunning Cobbler could be found in the writings of Boccaccio. The Female Cabin Boy revamped another old joke, involving women dressed as men, but was actually printed alongside Still so gently o’er me stealing which was taken from the opera by Bellini, La Sonnambula, first performed in England at the Royal Opera House in 1833.

37 The theme of The Cunning Cobbler could be found in the writings of Boccaccio. The Female Cabin Boy revamped another old joke, involving women dressed as men, but was actually printed alongside Still so gently o’er me stealing which was taken from the opera by Bellini, La Sonnambula, first performed in England at the Royal Opera House in 1833.![]() 38 Mixed messages are being given here which indicate how a ballad-printer may have used older and newer stock together. Charles Hindley and, later, Leslie Shepard both underlined such a practice.

38 Mixed messages are being given here which indicate how a ballad-printer may have used older and newer stock together. Charles Hindley and, later, Leslie Shepard both underlined such a practice.

Hindley, in describing Catnach’s output, indicated that the printer, in issuing all sorts of songs and ballads, ‘introduced the custom of taking from any writer, living or dead, whatever he fancied, and printing it side by side with the productions of his own clients’. He ‘naturally’ had a taste for old ballads; made sure to bring standard and popular song within reach of all - which often meant that he chose ‘the worst and the vilest’ of them as being suitable for street sale - and that ‘As a rule there are but two songs printed on the half-penny ballad-sheets - generally a new and popular song with another older ditty’.![]() 39

39

Of Pitts, Mr Shepard wrote that his stock contained ‘a mixture of the songs of stage or pleasure gardens, and good old-fashioned traditional country songs’; of chapbook style songsters (usually consisting of a single sheet folded into an eight-page pamphlet) which often had the title ‘Being a Choice Collection, of the Newest Songs Now Singing at all Public Places of Amusement’; and very early broadside ballads such as Captain Ward… Indeed, Mr Shepard credited Pitts with reviving a market for the older material. Pitts, he reckoned, ‘brought many old country songs to London, and circulated the latest hits of stage and pleasure garden in the countryside.’ ![]() 40

40

Mr. Shepard added that:

We do not know enough about Merry to confirm in full the family’s place in this context. It could be that the surviving Merry texts are but part of a larger output. Whatever the case, the tie-up in kind as set out above and below is clear enough.

There are, furthermore, clearly dateable Merry printings apart from the one or two mentioned in the second piece in this series - that is: the date given is the first available time at which they could possibly have appeared. The Old Folks at Home, a Stephen Foster song, is an example, first published in 1851.![]() 42

42

Donald’s return to Glencoe is a rather more unusual inclusion. Printings were put out by, amongst others, Harkness, Fordyce and Ross in the north of England. London printers include Paul and Ryle, Fortey and Such, all four of whom are relatively latecomers in the printing stakes. Any of these printers may have inherited the text, of course, from some other printer; or got it orally. Whatever the source, the overwhelmingly favoured reference where there is one in all these printings is to the French and Spaniards as Donald’s opponents in war.![]() 43 Known sung versions are to be found in the Grieg-Duncan collection and all but one (which dates from 1914) were noted during the period 1905-1910. Various dates for acquisition were given, either through oral means or from ‘broadsheet’, of some thirty, forty or fifty years before.

43 Known sung versions are to be found in the Grieg-Duncan collection and all but one (which dates from 1914) were noted during the period 1905-1910. Various dates for acquisition were given, either through oral means or from ‘broadsheet’, of some thirty, forty or fifty years before.![]() 44 Importantly, these, too, favoured French and Spanish conflicts. Admittedly, Spain and France were long-standing enemies of England but we might also think that these conflicts were those of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries - the Napoleonic wars. The Merry choice of material subsequently offered a small intrigue. Merry was, as far as is known, the only southern English ‘country’ printer to issue the piece. Moreover, Merry’s text, which otherwise follows the narrative line in the sung versions and other printings, has the startling inclusion of Russia and Persia as enemies, which would appear to set the narrative at the time of the Crimean War - 1854. This, in turn, is a printing date commensurate with several other Merry issues as discussed here.

44 Importantly, these, too, favoured French and Spanish conflicts. Admittedly, Spain and France were long-standing enemies of England but we might also think that these conflicts were those of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries - the Napoleonic wars. The Merry choice of material subsequently offered a small intrigue. Merry was, as far as is known, the only southern English ‘country’ printer to issue the piece. Moreover, Merry’s text, which otherwise follows the narrative line in the sung versions and other printings, has the startling inclusion of Russia and Persia as enemies, which would appear to set the narrative at the time of the Crimean War - 1854. This, in turn, is a printing date commensurate with several other Merry issues as discussed here.

The first appearance of the text of The Rose of Allandale is given as c.1835. The words are credited to a Charles Jeffreys (1807-1865) with the air to a Sidney Nelson (1800-1862).![]() 45 We have, then, a general period of time after which it is most likely that a Merry got hold of The Rose of Allandale.

45 We have, then, a general period of time after which it is most likely that a Merry got hold of The Rose of Allandale.

It was printed alongside Nancy in the Strand which indicates that ‘old’ and ‘new’ material need not have been separated by centuries. Nancy… is a light-hearted piece which refers to the appearance of a ‘Bobby’, to the Balmoral boot, and to

One more point may be made about The Rose of Allandale. It came, not from accepted ‘tradition’ (which would include much of our ‘old’ material) but direct from the drawing-room and, like the Foster piece, must have been absorbed into a printer’s treasure-chest because it rendered commercial success. One of the best examples of a writer plundered in this way is that of Charles Dibdin from whom songs such as Hot Codlins, Ben Backstay the Boatswain and, of course, Tom Bowling came and were taken into printers’ stock.![]() 47 Burns (Bonny Mary of Argyle, Highland Mary, The De’il’s away wi’ the Exciseman, Ye Banks and Braes o’ Bonny Doon and so on) was another writer so used though not to nearly the same extent. Other authors from whom material was taken who had achieved a status more than that afforded by minor scribbledom include Thomas Campbell and Thomas Moore.

47 Burns (Bonny Mary of Argyle, Highland Mary, The De’il’s away wi’ the Exciseman, Ye Banks and Braes o’ Bonny Doon and so on) was another writer so used though not to nearly the same extent. Other authors from whom material was taken who had achieved a status more than that afforded by minor scribbledom include Thomas Campbell and Thomas Moore.![]() 48 Hindley’s point about Catnach’s cavalier acquisition of text is equally well illustrated here.

48 Hindley’s point about Catnach’s cavalier acquisition of text is equally well illustrated here.

Another instance of a general period of time during which a piece may have been produced may be gauged in the text, Who’s your cooper?, where the subject is the crinoline dress which had appeared in England, made up of a framework of horsehair, in 1840. It was not until 1860 that the cage crinoline, which rested on a framework of steel wire, was adopted. The halfway house in the particular text was to

The Tax on Gin, with its reference to ‘Billy Gladstone’, has been dated by the Bodleian to (or around) 1854, and, presumably, comments on measures introduced in Gladstone’s second budget (1853) when, as chancellor of the exchequer in Aberdeen’s government, he raised duties on all spirits manufactured in Ireland to a level commensurate with those in England and Scotland. We may, in this ballad, then, be subject to something of a liberty in interpretation (a good story was never spoiled by historical accuracy).![]() 50 It is also worth noting that, apart from Merry, only Fortey, Disley and Such appear to have printed this piece, all beginning their printing mid-century or thereabouts and, so, perhaps, confirming such a date for the Merry issue. The theme may have been used in the way that newspaper reporting worked - sufficient unto the day. The drift is clear enough:

50 It is also worth noting that, apart from Merry, only Fortey, Disley and Such appear to have printed this piece, all beginning their printing mid-century or thereabouts and, so, perhaps, confirming such a date for the Merry issue. The theme may have been used in the way that newspaper reporting worked - sufficient unto the day. The drift is clear enough:

The ballad, then, reflects contemporary concerns and in a similar way to Who’s your butcher? and The Farmers, Millers and Bakers; but it was not necessary to attach a ballad to a specific date or occurrence except as a springboard. General propositions would often account for popularity (or otherwise); and older stock could do duty. There are plenty of songs which have updated references - like The Kerry Recruit, which seems first to have been issued as The Lawyer Outwitted and only then as The Kerry Recruit and which, moreover, got attached, in some sung versions, to the Crimean War. The French and Spanish connection already discussed above offers another possible example of a constant theme persisting in changed circumstances.

So - meat, in the first-named Merry piece, was being bought at ‘Ninepence to a Bob a pound’. At what date this was the case is not at all clear; but, as noted, apart from Merry only Disley and Such, beginning to print around the mid-century mark, issued this ballad.

The farmers, who refused to pay their workers enough to avoid hardship, were, in another Merry ballad (13 in list above), castigated along with millers and bakers. Again, it would be glib to automatically assume that Merry’s printing was to be attached to a specific social phenomenon but, in terms of the sort of general proposition noted above, agricultural distress and unrest as it can be observed from the cessation of war in 1815 up, certainly, until the Swing riots of 1830-1831, was rife in Britain and Ireland, despite some regional variance. It was not until mid-century that agriculture revived and even then labourers were hardly the most prominent beneficiaries. One respected commentator, Keith Snell, advances several possible reasons for the worst situation including the ravages of seasonal unemployment, the effects of enclosure and of the changes in Poor Law administration…![]() 51 The Merry ballad, in this light, would seem to be journalistic in tone and it can be no surprise that familiar targets were made prominent. Millers, in particular, were notorious for supposed dishonesty and can be found as targets throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries where popular disturbance occurred.

51 The Merry ballad, in this light, would seem to be journalistic in tone and it can be no surprise that familiar targets were made prominent. Millers, in particular, were notorious for supposed dishonesty and can be found as targets throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries where popular disturbance occurred.![]() 52 It is, finally, a fact in all this that Bedfordshire suffered badly from agricultural depression. As it happens, too, Merry seems to have been the only printer to have issued this piece. The Merry ballad, then, may be thought apposite: and this may even be a case of the issue of a genuinely local product - we can go no further than that.

52 It is, finally, a fact in all this that Bedfordshire suffered badly from agricultural depression. As it happens, too, Merry seems to have been the only printer to have issued this piece. The Merry ballad, then, may be thought apposite: and this may even be a case of the issue of a genuinely local product - we can go no further than that.

Apart from ballads which have a connection with historical actuality, we also find pieces associated with the contemporary or near-contemporary stage or the drawing-room such as The Light Guitar which was widely printed as broadside - by, amongst others, Pitts, Catnach, Wright (Birmingham) and Harkness (Preston). It came from a musical drama called Epaulette, sung by one, Madame Vestris.![]() 53 The composer was John Barnett, the writer a Henry (Harry) Stoe Van Dyk.

53 The composer was John Barnett, the writer a Henry (Harry) Stoe Van Dyk.![]() 54 The following lines give a flavour:

54 The following lines give a flavour:

Where Mary Anna was concerned, of the Merry ballads in the Bodleian library, The Silly Old Man and The Light Guitar (issued together), Nancy in the Strand and The Rose of Allandale (printed together), The Tax on Gin, Who’s your butcher?, Wait for the Waggon and The cot where I was born (the last two printed together) and Who’s your Cooper? were the ones that carried her initials:

or

Other notes contain tiny variants in the wording. If we are to interpret this information correctly, Mary Anna’s involvement at Castle Lane, not in the High Street, could well have come before her marriage and removal to Riseley; but it also seems to overlaps her father’s printing career in the High Street. This may, then, underline the possibility that the firm was printing out of two addresses at that time. Even so, the majority of pieces which have Mary Anna’s initials on them would seem, as demonstrated above, to be have been issued somewhere around the mid-century, after Clarke Barbour and his two sons ceased to print. One recalls the date of The Tax on Gin; the first time that the Balmoral boot appeared and the general period during which the crinoline was adopted…hardly conclusive but, certainly, suggestive. So, as first mooted above, we are left to wonder if Mary Anna helped her father or took on the business herself and prolonged its life until she married - or, indeed, both. The newspaper castigation of such female employment might take on added aura of exasperation in this light.

There is one other interesting find in Bedford which actually pursues the Sarah Dazley connection, that of a ballad written on the execution, in 1860, of one, Joseph Castle. Castle murdered his wife, Jane, in Luton; and there are newspaper accounts of the affair in which a familiar litany is recited: the state of mind of the prisoner, a statement from him concerning the murder (not, strictly speaking, a confession), a description of the execution itself and of the behaviour of the crowd, a full version of the sermon preached just before the execution…

One report described the crowd, some of whom appeared to have ‘travelled long distance on foot.’

Almost all of the windows in the vicinity of the gaol were occupied, and at several of them females were seated and standing.Another report indicated that:The total number was estimated at around fifteen thousand.

57

Although the vast concourse of people conducted themselves with the greater discretion during the execution, some of the visitors remained in the town till the evening, and becoming excited from the effects of drink broke into disorder and got fighting.One or two more details of such disorder were given; but it might seem that this brief mention was more in the nature of convention in reporting than it was a particular condemnation.

The Bedford Record Office copy of the Castle ballad can be found as part of a large piece entitled

Perhaps the Castle ballad formed part of the ‘double broadside’ cited by Mayhew as one of several versions of the same news - Mayhew described how:

First appears a quarter-sheet (a hand-bill…) containing the earliest report of the matter. Next comes half-sheets (twice the size), of later particulars or discoveries, or - if the supposed murderer be in custody - of further examinations. The sale of these bills is confined almost entirely to London, and in their production, the newspapers are for the most part followed closely enough. Then are produced the whole, or broad-sheets…and, lastly, but only on great occasions, the double broad-sheet…Mayhew then described how the process could be seen in the case of Rush (a few details of the Rush murder were given in the first piece in this series). The Merry ballad on Castle’s execution fits the description of the Rush affair, with illustrations and, probably, condensed newspaper accounts.

On the Merry Castle printing the ‘Copy of Verses’ headed the piece either side of a very simplified woodcut of someone on the gallows above strong walls and high above the crowd and which has echoes elsewhere…it could have been made from a pre-existent block, a common enough device. In this latter connection Leslie Shepard reported comments by William Hone who had approached the printer Batchelar with a view to buying some of the original crude blocks used for his carol sheets. Hone offered to replace the blocks with better quality engravings but Batchelar told him that "better are not so good; I can get better myself: now these are old favourites, and better cuts will not please my customers so well." ![]() 60

60

The Castle lines began with high rhetoric:

The accounts on the printing which followed underneath the ballad itself, like newspaper accounts, reveal Castle’s seeming inability to settle in his marriage, with one, Jane Whitecroft of Luton, and suggest that he suffered bouts of ‘irritable temper’. The couple quarrelled frequently; she several times threatened to leave him; he told her to do so; she determined and went and he followed her to her father’s house, somehow persuaded her to return home with him and then, on the way back, murdered her. These details can also be found in the two newspaper reports cited, with some expansion here and more brevity there.

A woodcut is set into the Bedford Record Office Merry piece depicting ‘the Murderous Attack’.

Castle went to the police to give himself up and the law then took its course. There are details of witness statements, including that of a surgeon. Castle, it was firmly stated, did not make a confession though he admitted his guilt (as one of the newspaper reports indicated); and he was described as ‘silent, passive and reserved’ - even callous. ‘Latterly’ he wrote an account of his life.

The Merry printing concluded with a brief account of the execution, beginning:

No execution having taken place here since that of Sarah Dazely, about 16 years ago, the concourse of people assembled might be counted by thousands. It was immense. The windows of the houses were filled with pretty faces, and the tops of the buildings and projections of all kinds of erections exhibited human beings in every direction.So that most of the paraphernalia surrounding the executions of the Wedmores and of Sarah Dazley, together with those instances cited in support, seems also to have surrounded the execution of Castle and found at least some mention on the Merry piece.62

Given the totality of evidence assembled above in respect of her possible involvement in Merry family affairs, it might seem that Mary Anna was the moving force; but this cannot be confirmed.

None of this adds up to anything startling but, given the small surprises that always occur in an individual stock, the collection of Merry printings as we have it seems to place the family amongst the mainstream printers that we know more about who issued something of a rag-bag of material. What also begins to emerge is that the operative period for the Merry imprint began at some stage before 1820 and ended somewhere in the 1860s, perhaps on the occasion of Mary Anna Merry’s marriage.

Roly Brown

Massignac, France - 23.7.03

Article MT129

2. This reference can be found in Court Manor Rolls (R/6/1/12/1d at the Bedford Records Office, dated 11 November 1831) and concerns a transaction on behalf of the Duke of Bedford.

3. Northants Mercury, 23rd May 1835.

4. In Bath, John Edward Rathbone became bankrupt (EFP 31st August 1854, p.8); in Blandford, Thomas Oakley (EFP 16tht November 1837, p.3); in Devonport no less than four printers within a short period of time - G. W. Hearle (EFP 18th February 1837, p.3), Thomas Holman (EFP 17th July 1834, p.3), James Johns (EFP 31st January 1833, p.3) and J. Mudge (EFP 29th February 1832, p.3). In Bristol, Messrs. Wright and Bagnall experienced a fire (EFP 14th November 1833, p.3), in Exeter Frederick John Godfrey (EFP 27th December 1855, p.6) and John Townsend (EFP 22nd March 1876, p.8), and in South Molton George Pook (EFP 28th February 1878, p.7). In Chard, John White's stock went up for sale (EFP 12th January 1804, p.1) and in Exeter that of T. Cunningham (EFP 2nd August 1838, p.2) and of Charles Risden (EFP 28th June 1849, p.8). In Taunton John Savage was described as a 'Debtor, seeking release from prison' (EFP 25th September 1817, p.10 and in Bideford John Wilson was declared to be a debtor (EFP 7th June 1849, p.4 - see also text below). All these references are examples only.

5. See EFP 15th February 1816, p.2 and 3rd February 1831,p.3. …again as examples. Further research may, naturally, change this perspective.

6. Both these printers will receive further attention in this series.

7. See Charles Hindley: The History of the Catnach Press,,,(Detroit: Reissued by the Singing Tree Press, Book Tower, 1969), p.43.

8. 'Swepson' was one of Clarke Barbour's father's names.

9. As suggested in the previous Merry piece, it could have been that the premises were situated on a corner…

10. Bedford records, Li/Lib/B 1/11/1.

11. Details of Wiltshire printers have been conveniently brought together in one volume by the Wiltshire Record Society, Vol. XLVII…1991 (Trowbridge, 1992). I am indebted to the staff at the Public Record Office in Trowbridge - where the volume was consulted - for their help during various visits. The quotations given here are but examples of a general trend.

12. The relevant Directories can be found in the Hampshire Local Studies Library in Winchester: Pigot's for 1828 and 1844; Slater's for 1852; and Gilmour's for 1854. I would like to thank the staff in Winchester for their help on numerous occasions. For a further account of Hampshire printers and the Hampshire book trade, which underlines the multiple-occupation nature of printers' activities, see John Oldfield: Printers, Booksellers and Libraries in Hampshire, 1750-1800 (Hampshire Papers 3, Hampshire County Council, Portsmouth, 1993).

13. This was the case during the latter part of the eighteenth century as well as in the nineteenth century. Trewman of Exeter, for example, took up business in insurance (see Exeter Flying Post, 19th September 1793). Again in Devon, nineteenth century insurance agents included the printers Theodore Parkhouse at Tiverton - for Eagle insurance (see EFP 19th June 1816, p.1c); T. Wood in Bath - life insurance but no further details (EFP 2nd April 1818, p.1c); and Jeffrey Binning in Bridgwater - no details (EFP 24th January 1828, p.3c). In Bristol. William Pine was a lottery ticket agent (EFP 17th November 1780, p.1d); William Bray in Launceston an agent for patent medicine (EFP 18th April 1793, p.3c); in South Molton Amos Tepper a lottery ticket agent (EFP 23rd January 1819, p.1c); L. Congden the same (EFP 17th January 1822, p.1c; and George Hearle the same (EFP 17th January 1822, p.1c) - the latter two in Plymouth. Liddell of Bodmin was both a seedsman (EFP 31st March 1793, p.1c) and a house agent (EFP 9th November 1797, p.1b). William Bray in Launceston was an agent for patent medicine (EFP 18th July 1793, p.2c). EFP has many other notices of different occupations, of house sales, the passing on of business, apprentices absconding, and selling of stock amongst printers. It should be added that I have not, as yet, been able to look in detail at other printers across the country (that is, other than in Devon, Hampshire and Wiltshire).

14. See EFP 4th February 1790, p.2.

15. See Leslie Shepard's John Pitts: Ballad Printer… (London, Private Libraries Association, 1969), p.55 where he also wrote that Catnach printed the same. For Fortey see, for example, Seventeen Come Sunday (Madden Reel 78, No. 944).

16. I have to thank Paul Burgess (Cheltenham) for details of Harward's career.

17. See Roy Palmer's piece on Willey as MT: Enthusiasms, 33.

18. This particular piece of information was found by Sue Edwards who discovered a simple error in the census records - different initials - which obscured John Swepson's whereabouts.

19. That is: in the previous Merry piece in this series.

20. Witnesses were Clarke Barber and his daughter, Sarah and all parties, including the labourer, John Wyant, signed.

21. She was described, oddly, as a 'sister', presumably to Elizabeth Moore, when we know that she only had one sister, Sarah. So far, no further information has been found concerning Elizabeth Moore.

22. Bedfordshire Times 9th October 1860, p.7. The piece was forwarded to me by the Bedford Record Office.

23. See Leslie Shepard: John Pitts… (London, Private Libraries Association, 1969), pp.73-74.

24. One or two more fragments of information are coming to light in respect of the Merry imprint including election addresses issues in 1837 and in 1841. Nothing, so far, has emerged that adds to our knowledge of ballad production

25. A written addition to the printed ballad has the information that the author was one, Sir. E. Dolben.

26. Bodleian Allegro archive as Johnson Ballads 1384B.

27. The Bedford Borough Collection contains Lord John Russell's opinions of the Methodists, printed in July 1830 (Bor BG 10/1/20), for instance, and see text below - Whitbread.

28. A piece with a single stanza on it (Bor BG 10/2/100) even suggested that Pym worshipped the Pope…presumably a reference to the debate on Catholic emancipation which achieved resolution in favour in 1829. Such were the changing allegiances that Tories - once, not too far distant, linked with Catholicism and Jacobites - could now throw such a taunt in the faces of their Whig opponents.

29. Song - on behalf of Trelawney…(Bor BG 10/1/179 - 37 above). No further details of Trelawney's career have been located yet.

30. The advertisement was dated 20th August 1842 (Bedford records, Li/Lib B1/11/1). Such information, if minor in nature, nonetheless fills out our knowledge of how a printing firm operated. Evidence from elsewhere can also be gathered. For instance, during the establishment of the Wootton Basset hiring fair in Wiltshire in the nineteenth century it appeared to be necessary to publicise its nature and, accordingly, handbills were printed at intervals. So that we find one printer, Dove, listed as having produced a hundred handbills during December 1836 which were then 'cried' at Swindon, Highworth, Faringdon, Cirencester, Calne, Marlborough and Devizes. Dove did a similar job in 1837and 1842 (two hundred handbills in each year); and shared duty with a Mr. Watts and a Mr. Ponting in 1840 (one hundred and twenty sheets). Another printer, Drake, printed two hundred handbills in 1838 (see:Wootton Basset Monthly Market and Hiring Fair Records, Vol. 3, 1836-1849, edited by Rosemary Church and published by the Wiltshire Family History Society, 1998…passim).

31. There is one so far unaccountable addition to possible Merry printings. This was a piece entitled The Agent's Lament, supposedly issued around 1868 (Bor BG 10/1/227), and is important because if it was, indeed, a Merry printing it must, perforce, extend the probable dates of operation of the Merry firm. It was apparently written by one, Drollt Allien…which may be a kind of acronym; and no printer's name appears on it - though Bedford Borough Records do attribute it to the Merry firm.

32. The Bedford records number them as BorBG 10/1/98, BorBG 10/1/96, and BorBG 10/1/101 respectively. The dates, presumably based on details included, were added by the Bedford Record Office.

33. 3rd July 1830; Bor BG 16/1/66.

34. For Webb's 'Song', see BorBG 10/1/34. William Henry Whitbread was MP between 1818 and 1837. Samuel, father (1720-1796) and Samuel, son (1758-1815) - William Henry's brother - also represented the Whig cause in Bedford. George William Russell (1790-1846) was the son of John (sixth Duke of Bedford) and first made a career in the army - he was, at one time, aide-de-camp to Wellington - was MP for Bedford in 1812; and then held several diplomatic appointments: for example, as English ambassador in Berlin between 1835 and 1841 when he was then made up to major-general.

35. The last two pieces have the Bedford Borough designations, BorBG 10/1/4 - 17th June 1818 - and BorBG 10/1/10 - 20th February 1820 - respectively.

36. Hindley described how Catnach printer took a small hand-press to Alnwick, where he had served his apprenticeship, in order to issue State of the Poll material in the 1826 Election. This was at the instigation of an old apprentice friend, Mark Smith, who felt that he himself could not get through all the work. As Hindley put it, 'The Alnwick election of 1826 promised to be a good one as regards printing': a clear indication of the demands of commerce - to which Catnach responded. (Hindley, op cit, p.75). Hindley added that Alnwick public houses were, for the duration of the election, made 'open'…a reminder of how election contests were fought before the 1832 Reform Act did away with what amounted to forms of open bribery. Hindley, indeed, described how busy printers were during the Reform debates 'in publishing, almost daily, songs and papers in ridicule of borough-mongering…' (op cit, p.87).

37. The well-known catalogues such as those from Walker, Birt, Fortey, Sanderson and others carry the titles. There are always surprises in both sources. Why would Williams of Portsea print The Female Cabin Boy and The Silly Old Man but not The Cunning Cobbler? Why would Willey of Cheltenham print only the first and third of them? The subject of choice and distribution remains one of the most obscure of areas in ballad-printing history and is most likely to remain so for no records of printers have turned up which might indicate, for example, when and under what auspices a 'country' printer bought in stock from London and then followed the practice of the source as regards issue.

38. See, for information on The Female Cabin Boy, Roy Palmer: The Oxford Book of Sea Songs (London, OUP, 1988), pp.202-203 where he uses a printing from Williams of Portsea whose operative dates he gives as between 1783 and 1847. Williams, as noted in the third piece in this series, is the subject of a forthcoming piece. In respect of La Somnambula: Vincenzo Bellini lived between 1801 and 1835. He got his libretto from one, Felice Romani, whose name appeared on the Merry printing. The very first performance of the opera was in Milan in 1831.

39. Charles Hindley, op cit, pp.222-223.

40. Leslie Shepard, op cit, p.44

41. Ibid, p.57-58.

42. It appeared under the auspices of Messrs. Firth and Pond in America and was issued as one of a number of Ethiopan Melodies as sung and composed by E. P. Christy. It turns out, though, that Foster had sold the rights to Christy and then got the song back the following year after which it appeared under his own name.

43. Ryle's and Paul's printings are on Madden Reel 78, Nos. 464 and 605 respectively and in the Bodleian Allegro archive as Harding B11 (932). Fortey's is on Madden Reel 78. No. 967. That from Such can be found in the Bodleian Allegro archive as Harding b. 16 (324a). Printings from the north mentioned in the text include Fordyce, Madden Reel 83, Nos. 309 and 310; Ross, Madden Reel 83, No. 580; and Harkness, Madden Reel 85 No. 674. There are also printings in the Bodleian Allegro archive from Walker (Durham) as Firth b.26 (513), from Forth in Pocklington (Manchester) as Firth b. 25(226); and also from the printer, Walter Birmingham, in Dublin as 2806 b. 9 (259). Harkness and Pearson truncated the text so that no mention of opponents can be found: 2806 c. 14 (10) and 2806 c.16 (288) respectively. There are other Allegro and Madden printings, some unattributed.

44. The suggestion was made that 'From the references to the Spanish and French we may assign the song to the early part of the last century' - that is, the nineteenth century. See The Grieg-Duncan Folk Song Collection, Vol. 5…(Edinburgh, Mercat Press…1995), notes, pp.632. For the texts and music see ibid, pp.458-474. Grieg was confident that the years after Waterloo were particularly rich in material referring to the Napoleonic wars; but - as examples - both the The Banks of the Nile and The Bonny Light Horseman, the former most likely referring to 1798 and the latter, perhaps, to the Peninsular War (1807-1814), seem to have taken earlier songs as inspiration. Certain 'Napoleonic' songs were, even more clearly, retrospective in character (Bonny Bunch of Roses is a prime example). Donald's Return…is but one of several returned-lover, broken-token songs of which, as near neighbours, The Plains of Waterloo and Mantle So Green, are particularly well-known but which have precursors. There are, as it happens, no southern English sung versions of Donald's Return…in the English Folk Song Revival. The song did cross the Atlantic and there are several American and Canadian versions - but these were all 'late'. Sam Henry, likewise, printed a 'late' version - the date of acquisition was 1936 (see Songs of the People, ed. G. Huntingdon, Athens and London, The University of Georgia Press, 1990, p.319). Lucy Broadwood got a version from Bridget Geary in 1906. The tune of this was 'learned as a child from some school-friends' and the words were completed 'from a ballad-sheet' (see JFSS 5, 1915, pp.100-102). There are recordings by Lizzie Higgins, Jeanie Robertson and Peta Webb but accompanying notes do not help us ferret out a possible date for genesis any more than does other known information.

45. For the dating of The Rose of Allandale see Derek Scott's survey, The Singing Bourgeois (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2001), p.101. Jeffreys (sometimes spelled 'Jefferys') and Nelson collaborated on other songs such as I Will be Happy Too (c. 1836-1843), Music at Nightfall (c. 1843) and Bonny Mary of Argyle. Nelson is known to have associated with the more famous composer, Thomas Haynes Bayley, and, according to Derek Scott, was also, with Jeffreys, the publisher of a musical annual, The Queen's Boudoir (see Scott, op cit, p.52).

46. The Bodleian Allegro archive copy carries the suggestion that the piece is to do with prostitution.

47. The Bodleian Allegro archive lists over a hundred and sixty Dibdin songs in broadside form.

48. Campbell's pieces include Exile of Erin, The Soldier's Dream, Poor Dog Tray and The Wounded Hussar. Moore's contribution included The Minstrel Boy, Believe me if all those enduring young charms, The Canadian Boat Song, The Legacy and The Last Rose of Summer.

49. There are two other light pieces of the same kind: Who's your hatter? and Who's your butcher? to be found. Ryle in London, Pratt in Birmingham and Wright in Edinburgh printed the first; Disley and Such the second. Dates of operation for all these printers and a few internal details suggest a mid-century period of issue - for instance, a Queen appears in the first and this must have been Victoria…there are no records of earlier printings. If there was something of a fashion for such pieces it might help to confirm the date of printing of Who's your cooper? For the Butcher…(apart from Merry - text below) see Disley in Madden Reel 81 No. 241 and Such in the Bodleian Allegro archive as Harding B 11(4176). For the Hatter… see Ryle in Madden Reel 78 No 593; Pratt in the Bodleian Allegro archive as Firth c (21(125); Wright, same source, as Firth c 21 (124); Ryle, same source as Firth b 26(252); and an issue without imprint, same source, as Harding B 11 (2616).

50. On the other hand, increased taxes on spirits were a measure reflective of difficulties for the particular government which led it to increase stamp duty and duties on sugar and malt as well - since measures previously introduced had not given the Chancellor adequate revenue for governmental administration, especially on the eve of the Crimean War. So that Gladstone's 1853 proposals to introduce successive reductions in income tax until it could be abolished came immediately un-stuck. Gladstone courted disaster by insisting that the war be financed out of revenue rather than by borrowing; and was forced to concede the point, raise loans, and, ultimately, to accept defeat - he resigned as chancellor in 1855…There are many accounts: in Morley's Life…, for instance; and in K. Theodore Hoppen: The Mid-Victorian Generation 1846-1886 (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1998 paperback edn.). It could be said to be typical of popular apprehension that the ballad seized on but a partial aspect. For Disley's printing, see Madden Reel 81, No. 222.

51. See K. D. M. Snell: Annals of the Labouring Poor…(Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995 paperback edition), pp.60-61. The MacQueen cited in Merry ballads actually produced governmental reports on the problems which were issued in 1830 and 1831.

52. John Stevenson's Popular Disturbances in England 1700-1832 (London, Longman, 2nd edition, paperback, 1997) and E. P. Thompson, in Customs in Common (London, Penguin Books, 1993 paperback edition), both offer accounts of food riots. It would not be safe simply to extrapolate; but it may have been that the ballad was in revived form.

53. Madame Vestris was Eliza Vestris (1797-1856), a popular actress, opera singer and, later, manager of the Olympic Theatre, London, where she was noted for introducing good décor and costume and was particularly famed for her cross-dressing parts. Other songs associated with her name included The Arab Steed, another piece to appear extensively on broadside printings and; Cherry Ripe; Buy a Broom ('From Teutchland I came with my light wares all laden'); and My Heart's True Blue ('I will never leave my native shore'). Pitts and Catnach both included some of her songs in broadside sheets. .

54. John Barnett (1802-1890) was - coincidentally - born in Bedford, son of a German immigrant. His most notable musical efforts were the operas, The Mountain Sylph (1834) and Fair Rosamund (1837). Van Dyk (1798-1828) combined with Barnett more than once: A Harper Sat By A Tranquil Stream is another example, dating from 1827; as is Music, moonlight, love and flowers. In 1822, Van Dyk issued Theatrical Portraits: with other poems, in London. His very obscurity (relative) may hint at the ephemeral nature of such material but he is also an example of the breadth of source - in scribbledom - tapped by Merry and other printers. Van Dyk's date of demise may even qualify him as part of 'old' rather than contemporary material.

55. The cot…appeared under several imprints including that of Henson of Northampton in the Bodleian Allegro archive as Firth c 14(347); and, in the same source, as issued by de Marsan in New York around 1860: Harding B 18(197). Such evidence, if a little thin, still suggests a first issue mid-century.

56. I am indebted, as on so many occasions, to Roy Palmer (Malvern) for the Kilgariff reference. Other information comes from the Roud index where it is noted that, in an edition of The Christy Minstrels' Song Book (n.d.; but in Vol. 1, pp.15-17) authorship is credited to a P. G. Krauss. This may just be a reflection of appropriation in an American market. Indeed, a Bishop Buckley may well have taken out copywrite on an anonymous piece. It was so filed in America under such a name 24th May 1851; but this was, apparently, an R. Bishop Buckley and his dates were 1810-1857. The confusion has yet to be resolved. An American Civil War piece, The Brass-Mounted Army, words by 'an anonymous soldier of Col. A. Buchel's Regiment', was based on the Waggon.

57. The Bedfordshire Mercury, 31st March 1860.

58. Bedfordshire Times and Independent, 3rd April 1860.

59. Henry Mayhew: London Labour and the London Poor…(London, Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., 1967), Vol. I, p.281.

60. See Leslie Shepard's op cit, pp.63-64. Hindley, op cit, p.223, has descriptions of how printers used blocks entirely inappropriate to the subject-matter but which, presumably, were also, in some sense, 'favourites'. Three examples will suffice. As Hindley put it, '"The Heart that can feel for another" is illustrated by a gaunt and savage looking lion; "When I was first Breeched," by an engraving of a Highlander sans culotte; "The Poacher" comes under the cut of a youth with a large watering-pot tending flowers…'

61 Another ballad, printed by Plant of Nottingham, has emerged with similar propensities to that of Mary Ann Ashford - on the execution, 'for the wilful murder of Elizabeth Wood', of Sarah Smith, aged 28 at her death, in Leicester on 26th March 1832. The following stanza gives a flavour:

62. The spelling is interesting given the variants as noted in the previous Merry piece in this series.

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |