Article MT143

The Birds Upon the Tree

and other traditional songs and tunes

Musical Traditions Records' second CD release of 2004: The Birds Upon the Tree (MTCD333), is now available. See our Records page for details. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the record, or who might find the small print hard to read, I have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here.

[Track Lists]

[Introduction]

[The Performers]

[The Songs]

[The CD]

[Credits]

| 1 - | The Birds Upon the Tree

| Charlie Bridger | 2:21

|

| 2 - | The Bonny Labouring Boy

| Bob Blake | 2:47

|

| 3 - | The Man in the Moon

| Scan Tester & Rabbidy Baxter | 2:35

|

| 4 - | Three Jolly Boys

| George Spicer | 1:42

|

| 5 - | Henry My Son

| Fred Jordan | 2:42

|

| 6 - | Mr Lobski

| Archer Goode | 2:18

|

| 7 - | When I Was a Boy

| George Fradley | 3:26

|

| 8 - | The Seeds of Love

| Unknown singer | 2:48

|

| 9 - | Poor Dog Tray

| Packie Manus Byrne | 3:54

|

| 10 - | The Mulberry Bush

| Harry Cockerill | 2:19

|

| 11 - | Jack and the Squire

| Freda Palmer | 0:48

|

| 12 - | The Bonny Light Horseman

| Jacquey Gabriel | 3:19

|

| 13 - | The Doughty Packman

| Ray Driscoll | 2:14

|

| 14 - | The Holly and the Ivy

| Ivor Hill & family | 2:23

|

| 15 - | Little by Little and Bit by Bit

| Charlie Bridger | 2:36

|

| 16 - | I'll Sing of Martha | Freda Palmer | 1:35

|

| 17 - | Dales Waltz

| Harry Cockerill | 1:46

|

| 18 - | A British Soldier's Grave

| Archer Goode | 4:31

|

| 19 - | Billy Brown

| Freda Palmer | 1:39

|

| 20 - | The Old Drunken Man

| Alice Francombe | 3:40

|

| 21 - | Feyther Stole the Parson's Sheep

| George Fradley | 2:05

|

| 22 - | The Oyster Girl

| Harry Cockerill | 1:29

|

| 23 - | Johnny o' Hazelgreen

| Packie Manus Byrne | 4:31

|

| 24 - | Nowt to do wi' Me

| George Fradley | 4:26

|

| 25 - | What is the Life of a Man

| Archer Goode | 3:17

|

| 26 - | Wassail Song

| Alice Francombe | 4:39

|

| 27 - | Barbara Allen

| Debbie & Pennie Davis | 2:13

|

| | Total: | 73:58

|

Introduction:

The Birds Upon the Tree is a continuation of previous Musical Traditions' CDs such as Up in the North, and Down in the South and Here's Luck to a Man and contains further material that I have collected in England over the years. When Up in the North, and Down in the South was reviewed in the Folk Music Journal mention was made of the fact that it only contained 'folk songs' and that many of the singers' 'other' songs had been omitted. And this, of course, is correct. You can only include so many songs on a CD and, as I started out collecting 'folk songs' many years ago, I was happy to include examples of these songs. But, folk-singers do sing other songs as well as 'folk songs' (and, please, let's not get into any arguments here as to what defines a 'folk song'!) and so I have tried in this CD to select as wide a variety of songs as possible - bearing in mind that many of the songs from my collection are currently available elsewhere, or will shortly be made available elsewhere. Yes, there are some 'folk songs' on this CD (the sort of thing that Cecil Sharp was happy to collect), but there are also examples of other types of songs and music (the sort of thing that dear old Cecil did not collect).

Sharp, and his Edwardian colleagues Ralph Vaughan Williams, George Butterworth, Lucy Broadwood etc., collected versions of Barbara Allen, The Old Drunken Man, The Bonny Light Horseman, Jack and the Squire, Henry My Son, The Seeds of Love and The Bonny Labouring Boy which, by their definitions, were all 'folk songs'. They were also happy to collect Irish and Scottish songs and ballads should they encounter them. Frank Kidson noted a number of Scottish songs whilst on holiday in the Scottish Borders and Cecil Sharp collected several Irish songs from Irish singers in England. Most English broadside printers issued Irish and Scottish songs on their respective sheets and these songs must have been brought to England by Irish or Scottish singers. This is why I have included two songs, Poor Dog Tray and Johnny o Hazelgreen from an Irish singer, Packie Manus Byrne, who lived in England for many years. Packie had picked up both songs in Donegal, but, like many of his forbears, he had sought work in England and had been happy to share his songs with an English audience.

Several of the other songs are by known composers and were popularized by singers in the Victorian Music Halls. These include The Birds Upon the Tree, It's Nowt to do wi' Me, When I Was a Boy, Little By Little and Bit by Bit, A British Soldier's Grave, I'll Sing of Martha and Billy Brown. One song (Three Jolly Boys) could equally be considered a 'folk song' or else a 'Music Hall' song (again depending upon how we get round to defining these terms!). There are also two examples of folk carols (The Holly and the Ivy and a Wassail song), a cante-fable (Feyther Stole the Parson's Sheep) and a couple of oddities (Mr Lobski and The Doughty Packman). The first may be an example of an early 19th century political squib, while the second is either very old indeed, or, more likely, is a Victorian or Edwardian attempt to create a folksong. There are also a handful of instrumental tracks, including one that was popularised on early gramophone records by a Music Hall performer.

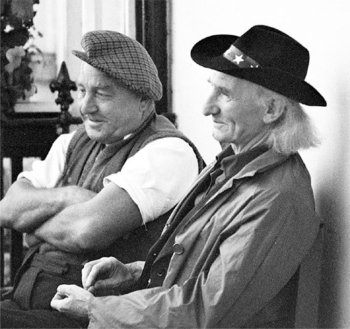

The Performers:

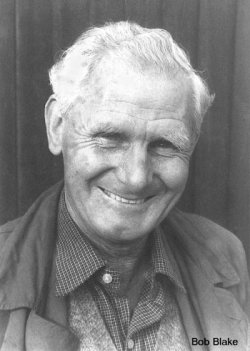

It has often been said that folksingers and musicians, unlike professional folklorists, have never been bothered with definitions as to what they sing or play. Bob Blake, unlike the other singers heard here, seems to have been unique in that he only sang folksongs! Years ago I told another collector that I was going to see Bob and was surprised when that collector seemed indifferent to Bob, saying that he didn't consider Bob to be a folksinger. Perhaps I should have queried what he meant, but I didn't. Over the years I visited Bob on a number of occasions and, whilst he was quite nervous, he did sing me some fine songs, most of which were issued on various LPs (and reissued on CDs). Following his death, Bob's daughter kindly let me see some manuscripts that Bob had assembled. Most of the songs that I had recorded were there, along with details of the books that he had learnt them from! Bob had been born and brought up in south London and had only moved to Sussex when he was nineteen. I now suspect that he had heard singers in the pubs around Horsham and, wanting to join in, had borrowed some books from the library so that he too could sing the odd song or two. Over the years he developed his singing style, so that when collectors such as myself visited Horsham we were only too delighted to record him. Four of Bob's other songs can be heard on Up in the North and Down in the South (Musical Traditions MTCD311-2).

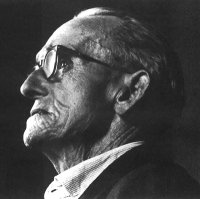

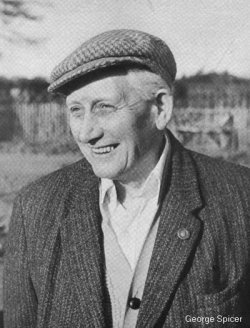

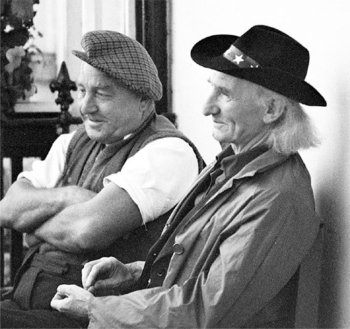

I went to visit Charlie Bridger at his home in Kent because I had been told about his superb version of the song Three Maidens a-Milking Did Go (available on the veteran CD Down in the Fields VTC4CD. Two other songs, The Folkestone Murder and The Zulu Wars, will be reissued on future Veteran CDs). Charlie had worked for most of his life at a near-by stone quarry and I am sorry that I only managed to see him on one occasion. Sussex concertina player Scan Tester was another performer that I only recorded once, although I bumped into him on a number of other occasions over the years. Scan's double LP I Never Played to Many Posh Dances (Topic 2-12T455/6) and the accompanying booklet of the same name paint a detailed picture of this outstanding musician. Scan is accompanied here by his life-long friend, the tambourine player Ernest Edward 'Rabbity' Baxter. Scan had first met Rabbity at The Stone Quarry at Chelwood Gate c.1930 and the pair had played together ever since. Like many of the older Sussex players, Rabbity was adept at using all parts of the tambourine (drum, rim etc.) when he played. Two further tracks by Scan and Rabbity, also recorded in the Balcombe Half-Moon, can be heard on the Topic CD Rig-a-Jig-Jig. Dance Music of the South of England (TSCD659). George Spicer was also living in Sussex when I got to know him, although he was originally from the area around Dover in Kent. And it was as a young man in Kent that he learnt most of his songs, from family and friends. Further recordings can be heard on two other Musical Traditions CDs (MTCD309-10 & MTCD311-2), a Veteran CD (VTC4CD) and a couple of Topic CDs (TSCD663 & 664).

The late Fred Jordan must be one of the best-known English country singers today. He was 'discovered' by the BBC in 1952 and, for the rest of his life, he continued to delight audiences throughout the length and breadth of the country. I first recorded Fred at his home in 1965. Some of these recordings, together with many others, have been lovingly assembled by John Howson who has issued them on a superb double CD A Shropshire Lad (Veteran VTD148CD). I also met the Irish singer and whistle-player Packie Manus Byrne at the same time. Our paths kept crossing, first when we were living in London, then Manchester, and then back in London again. Many more of my recordings of Packie can be heard on another of John Howson's CDs, Donegal & Back (Veteran VT132CD). Like the Fred Jordon set, Packie's CD also comes with excellent notes.

George Fradley had been raised in a musical family. Most of the family were entertainers in one way or another and the family ran a troupe of performers that sang and performed humorous sketches in local village halls. George knew all sorts of songs, from classic Child ballads to songs from the 1920s. You can hear him singing Last New Year's Eve and The Two Sisters on Veteran VTC4CD and a further eight songs are scheduled to be released on forthcoming Veteran CDs. Sadly, Tufty Swift, who accompanied George on a number of tracks, died some years ago. Tufty was still young when he died and we lost a good friend of folkmusic with his passing. Ray Driscoll was also from a musical family, his Irish grandmother teaching him such songs as Rocking the Cradle. Ray also picked up songs from the streets of south London when he was a child and from singers in Shropshire a few years later. He had returned to London when I met him in the 1980s and was eager to pass on his songs to a younger generation.

Harry Cockerill was a farmer from beautiful Wensleydale. He played the accordion for local dances and a selection of his other tunes can be heard on MTCD311-2. The remaining singers on this CD were all from the Cotswolds of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire. Archer Goode - 'Goode by name and good by nature' - was originally from Abergavenny, where he had worked with horses on rural farms. He had befriended the Warwickshire Morris dancer Sam Bennett in the 1930s when Sam would go to Wales on holiday. Sam taught Archer quite a number of songs which I recorded from him in Cheltenham where he was then living. Jacquey Gabriel was active in the Cotswold folk circuit when we met. As a girl in Suffolk she had learnt a number of songs from her father who would encourage her to sing in local pubs to raise a bit of cash. Jacquey can be heard singing another of her father's songs, Giles Collins, on MTCD311-2. Freda Palmer was originally from the village of Leafield. As a girl, she worked making gloves in a cottage with her aunt. The pair would sit facing each other and her aunt would sing to help pass the time. And that's how Freda learnt her songs, by listening to her aunt. "Did you ever join in?" I once asked her. "Oh, no", she replied. "I can't sing. I just used to listen to her." You can hear five of Freda's other songs on MTCD311-2 as well as a couple more on two Topic CDs O'er his Grave the Grass Grew Green (TSCD653) and Who's that at my Bedroom Window? (TSCD660).

I had met Archer Goode and Jacquey Gabriel through Gwilym Davies, and it was Gwilym who also took me to see Ivor Hill and Alice Francombe. On both occasions we drove to their respective homes during dark winter evenings and I have little memory of where, exactly, we were going. I do know that the Hill Family made us extremely welcome and it was sad news indeed to hear that Ivor had died in a car accident shortly after we recorded some of his songs. One other piece by Ivor, List Our Merry Carol, will be reissued on a future Veteran CD in the next year or so. Gwilym wanted to meet Alice Francombe so that we could record her version of the local Wassail Song. This we did, but I must say that I was really happy when she came out with her version of the ballad The Old Drunken Man. This was one of the songs that I heard my grandfather sing and it brought back all kinds of happy memories to me. In fact, listening again to all these recordings, I am reminded of the pleasures that were involved in their making. All of the singers went out of their way to be helpful - no easy task when a stranger sometimes knocks on the door asking about 'old songs'! Most of the singers were elderly when we met and so it was a delight to hear Debbie & Pennie Davis, two of the youngest singers that I have recorded, singing (and clearly enjoying) the old ballad of Barbara Allen. We made the recording in their parents' caravan, the adults having been pushed outside, because the girls refused to sing in their presence, and I was reminded of something that Zora Neale Hurston had said in her book of Negro folklore, Mules & Men (1935) - 'Folk-lore is not as easy to collect as it sounds. The best source is where there are the least outside influences and these people, being usually under-privileged, are the shyest.'

As ever, I am eternally grateful to all the singers and musicians heard on this CD. Indeed, I am grateful to all the people who have let me record their songs, stories, music and folklore over the years. Without them, the world would have been a poorer place.

The Songs and Tunes:

Roud numbers quoted are from the databases, The Folk Song Index and The Broadside Index, continually updated, compiled by Steve Roud. Currently containing more than 261,000 records between them, they are described by him as "extensive, but not yet exhaustive". Copies are held at: The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, London; Taisce Ceol Duchais Eireann, Dublin; and the School of Scottish Studies, Edinburgh. They can also be purchased direct from Steve at Southwood, Maresfield Court, High Street, Maresfield, East Sussex, TN22 2EH, UK. E-mail: sroud@btinternet.com

Child numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child, Boston, 1882-98. Laws numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in American Balladry from British Broadsides by G Malcolm Laws Jr, Philadelphia, 1957. Greig numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in The Greig/Duncan Folk Song Collection, 8 Volumes. Aberdeen University Press/Mercat Press. 1981 / 2002. Sharp numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in Cecil Sharp's Collection of English Folk Songs edited by Maud Karpeles, 2 Volumes. London, 1974.

The CD:

1. The Birds Upon the Tree (Roud 1863)

Charlie Bridger. Stone-in-Oxney, Kent. 1984.

Oh, I am a happy fellow; my name is Tommy Bell

I don't care for your billiards nor game of bagatelle.

A-rambling in the country; a country life for me,

And listen to the little birds a-singing on the tree.

Chorus:

Oh, the birds upon the trees, oh, the bird upon the tree.

Oh what a pretty sight it is, the little ones to see.

You talk about your music, the sweetest song to me,

Is the warbling of the little birds a-singing on the tree.

Oh, I often lose me temper; it puts me in a rage,

To see a little dicky bird imprisoned in a cage.

So I burst the bars asunder and set the prisoner free,

And hear the song of liberty while singing on the tree.

Oh, there's little Maud the miller's maid who is to be me bride

We often take a ramble through the meadows side by side.

And when we settle down in life our cottage it shall be,

Where we can hear the little birds a-singing on the tree.

The Birds Upon the Tree was written by the American W C Robey and first published in New York in 1882. Interestingly, Percy Grainger noted a version of the song in 1905 from the great Lincolnshire singer Joseph Taylor. And, as The Birds, it is sung by Tom Brodie, of Rockliffe / Wreay, Cumberland,on Pass the Jug Around (Reynard Records RR 002, reissued on Veteran VT142CD).

2. The Bonny Labouring Boy (Roud 1162. Laws M14)

Bob Blake. Near Horsham, Sussex, 1974.

As I walked out one morning,

As I walked out one morning,

Being in the blooming spring.

I heard a lovely maid complain,

She grievously did sing.

Saying, "Cruel was my parents,

And did me so annoy.

And will not let me marry with,

My bonny labouring boy."

"Young Johnny was my true love's name,

As you shall plainly see.

My parents did him employ,

Their labouring boy to be.

To harrow, reap and sow the seed,

And to plough my father's land,

And soon I fell in love with him,

As you may understand."

"My father stepped up one morning,

And he seized me by the hand.

He swore he'd send young Johnny

Unto some foreign land.

Then he locked me in my bedroom,

My confort to annoy.

And he left me there for to weep and to mourn

For my bonny labouring boy."

"My mother stepped up next morning,

These words to me did say:

'Your father hath intended to

Appoint your wedding day.'

To this I made no answer,

Nor dared I to complain.

But till I wed my labouring boy

I'll single here remain."

"Oh, his cheeks are like the roses,

His eyes are black as sloes.

He smiles in his behaviour

Where're my true love goes.

He is manly, neat and handsome,

His skin as white as snow,

In spite of my parents

With my labouring boy I'll go."

So fill the glasses to the brim,

Let the toast come early round.

Here's a health unto the labouring boy

Who ploughs and tills the ground.

And when his work is over,

His home he will enjoy.

Oh, happy is the maid that weds,

With the bonny labouring boy.

Parental opposition to a young person's sweetheart has long been a mainstay of the broadside ballad industry and The Bonny Labouring Boy is a classic example of the genre. London printers Fortey, Such and Disley all issued the song on their respective 19th century sheets, while Dublin printers Birmingham and Nugent issued the song in Ireland. Harry Cox sings a fine version on his Topic double CD The Bonny Labouring Boy (TSCD512D) and a 1946 recording by the Irish singer Paddy Beades,  originally issued on a 78 rpm disc, can be heard on another Topic album - Come All My Lads that Follow the Plough (Topic TSCD655). There is also a recording by Tony Harvey of Suffolk on the Veteran CD Songs Sung in Suffolk (VTC2CD).

originally issued on a 78 rpm disc, can be heard on another Topic album - Come All My Lads that Follow the Plough (Topic TSCD655). There is also a recording by Tony Harvey of Suffolk on the Veteran CD Songs Sung in Suffolk (VTC2CD).

3. The Man in the Moon

Scan Tester & Rabbity Baxter. The Half Moon, Balcombe, Sussex, 1963.

Scan never told Reg Hall where he got this waltz. Reg always assumed it was one of his first tunes and has certainly never come across it anywhere else. If you take the Bampton Morris tune, The Maid of the Mill, and play it as a waltz, you end up with something very similar to The Man in the Moon.

4. Three Jolly Boys (Roud 1710)

George Spicer. Selsfield, Sussex, 1974.

You're courting a milk-maid, aye, sir, aye.

You're doing the same, no, sir, no.

Is he, or is he not, aye, sir, aye.

Then you cannot deny it, no, sir, no.

Chorus:

Chorus:

Oh, one says aye, the other says no,

But we're three jolly boys all in a row.

In a row, in a row, in a row, in a row.

We're three jolly boys all in a row.

This maid had a baby, aye, sir, aye.

You were the father, no, sir, no.

Was he, or was he not, aye, sir, aye.

Then you cannot deny it, no, sir, no.

You'll pay for a gallon, aye, sir, aye.

You'll do the same, no, sir, no.

Will he, or will he not, aye, sir, aye.

Then you cannot refuse, no, sir, no.

Spoken That's all I can remember of that, you know.

The Liverpool Spinners used to sing a version of this. Part of their text, and most of the tune, came from a publican's son in Oldham, Lancashire. The rest came from the late Eric Winter, editor of Sing magazine, who printed the song in the March, 1962, edition of the magazine.

5. Henry my Son (Roud 10, Child 12, Greig 209, Sharp 4)

Fred Jordan. Washwell Cottage, Corve Dale, Shropshire, 1964.

'Where have you been all day, Henry my son?

'Where have you been all day, Henry my son?

Where have you been all day, my beloved one?'

'In the meadow, in the meadow.

Oh, make my bed, I've a pain in my head,

And I want to lie down.'

'Who gave you poison berries, Henry my son?

Who gave you poisoned berries, my beloved one?'

'Sister, mother. Sister, mother.

Make my bed, I've a pain in my head,

And I want to lie down.'

'What will you give your father, Henry my son?

'What will you give your father, my beloved one?'

A rope to hang him, a rope to hang him.

Make my bed, I've a pain in my head,

And I want to lie down.'

'What will you give your mother, Henry my son?

'What will you give your mother, my beloved one?'

'All my jewels, all my jewels.

Make my bed, I've a pain in my head,

And I want to lie down.'

'How will you have your grave, Henry my son?

How will you have your grave, my beloved one?'

'Deep and narrow, deep and narrow.

Oh, make my bed, I've a pain in my head,

And I want to lie down.'

Professor Child called this Lord Randal and gives over a dozen examples. Attempts have been made in the past to try to tie this ballad to an actual event, usually to the family of Ranulf, sixth Earl of Chester (d.1232), but as it is known in one form or another all over Europe, this has never been successful. Child noted that the ballad was popular in Italy c.1629, so it is probably quite an old story. Like the ballad Edward (Roud 200. Child 13), we have little idea of what actually lies behind this apparently motiveless murder. Not that this has bothered singers, who continue to enjoy the piece. Usually we find that the ballad's victim has been poisoned by eating either 'sma fish', snakes or eels. But Fred's version, with its 'poison berries', reminds us of another Shropshire version, Ray Driscoll's The Wild, Wild Berry (EFDSS CD02 A Century of Song). There are quite a number of other versions available at the moment, including those by George Spicer (MTCD 311-2), George Dunn (MTCD 317-8), Gordon Hall (Country Branch CBCD095) and Joe Heaney (Topic TSCD518D - this latter being sung in Irish). Jeannie Robertson's superb version, Lord Donald, is regretfully only available in a truncated form (along with similar versions from Elizabeth Cronin, Thomas Moran, Colm McDonagh and Eirlys & Eddis Thomas) on the CD Classic Ballads of Britain & Ireland - volume 1 (Rounder CD 1775).

6. Mr Lobski (Roud 18304)

Archer Goode. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, 1975.

Young Lobski said to his ugly wife

'I'm off for tomorrow to fish, my life.'

Said Mistress Lobski, 'I'm sure you ain't,

You brute, you are going to gallivant.

To gallivant, to gallivant.

You brute you are going to gallivant.'

What Mistress Lobski said was right,

Gay Mister Lobski was out all night.

Ne'er went to fish, I knew quite well,

But where he went to I shall not tell.

I shall not tell, I shall not tell.

But where he went to I shall not tell.

Next morning Mister Lobski knew

He'd caught no fish, so he bought a few.

Thinks he: My wife won't smoke my plot,

And she may bite, though the fish did not.

Though the fish did not, though the fish did not.

And she may bite, though the fish did not.

As Mister Lobski's wife drew near

Said she: 'What sport have you had my dear?'

'The river,' said he, 'was full of rats,

So I've only caught you a dozen sprats.

A dozen sprats, a dozen sprats.

I've only caught you a dozen sprats.'

'A dozen sprats, base man,' said she.

'What, catch in the river the fish of the sea?

You draw long line Mister Lobski I know,

But still you draw a much longer bow.

Much longer bow, much longer bow.

But still you draw a much longer bow.'

Mr Lobski was printed on a broadside by John Pitts, sometime during the first quarter of the 19th century. It also appeared in volume 1 of The Universal Songster (London, 1832). A slightly earlier song, Mrs Lobski's Rout, was printed by T Evans of Long Lane, London. This begins:

Mrs Lobski sold sprats and shrimps they say,

And Will the Plaisterer, she married t'other day,

By taking her to church, he whitewash'd her no doubt

And so she was resolv'd to have a merry bout.

Fol de rol, &c.

According to John Holloway and Joan Black (Later English Broadside Ballads, 1979, pp. 108 - 09) this could be a political satire against the Duke of Clarence (who became William IV in 1830) and his mistress, the actress Mrs Dorothea Jordan (1762-1816). The song is full of disguised meaning. In the late 18th century 'sprats' and 'shrimps' were terms used for whores, and 'gallivant', when used as a noun, meant a brothel. Even the name 'Mrs Lobski' is suggestive, and may come from 'Lobster pot', a slang term for the female sex organs.

7. When I Was a Boy (Master George) (Roud 18305)

George Fradley. Sudbury, Derbyshire, 1984.

When I was a boy I went to school

And picked up lots of learning.

One day my feyther said to me,

'Your keep you must be earning.'

I took the milk round, fed the pigs,

'Til one fine day my feyther said ,

'How d'ye like to serve the King?'

And I said, 'Why feyther, reyther.'

How'd I like to serve the King.

Ha, ha, ha. Ha, ha, ha.

I said, 'T'would be a champion thing.'

Ha, ha. Ha, ha, ha.

I scratch me head and then I thought,

'To serve the King, be very fine sport.

I wonder whether he want a pint or a quart.'

Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha.

The river it be full of fish,

To catch 'em be a problem.

The city chaps with rods and lines

Do find it hard to nobble 'em.

A bloke once asked me what to do,

And I told him that he ought 'ter

Go home and fetch their pepper pot

And sprinkle it on the water.

Sprinkle it on the water thick.

Ha, ha, ha. Ha, ha, ha.

'Twill make 'em sneeze and they'll come up quick

Ha, ha. Ha, ha, ha.

Just sprinkle it on the water thick, it will

Make 'em sneeze and they'll come up quick,

Then you hit 'em on top of the 'yead

With a great big stick.

Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha.

We've got a fox down on our farm,

It killed our black menorca.

My dad shot at it with a gun,

And he wounded our prize porker.

Said I, 'Dad, foxes can't bear guns,

At the sight of one they'll sail off,

So why not get a great big knife

And cut the varmin's tail off?

Cut the varmin's tail off, Dad.

Ha, ha, ha. Ha, ha, ha.

He said, 'You be a foolish lad.'

Ha, ha. Ha, ha, ha.

'Oh, no I be'ant,' I laughed and said,

'cut off his tail, he'll soon be dead,

If you cut close enough to the varmin's yead.'

Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha.

As I was going down the lane one day

A motor car drew past me.

The man who drove it pulled it up,

And this is what he asked me.

Said he, 'How be you, Master George?'

'Twas queer how he should know me.

'Where do this road go to my lad?

I wondered if you'd show me.'

'Where does this road go, my boy?'

Ha, ha, ha. Ha, ha, ha.

I said, 'I don't know, Master. Why?'

Ha, ha. Ha, ha, ha.

'Where do it go? That do seem queer.

I've lived round here for twenty year,

And it int'a gone away sin' I bin' here.'

Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha.

I'm sure George told me that he had learnt this one from an old 78rpm record, although he was unable to say which performer had made the record. And I'm at a loss as well, because I cannot trace it either. The final verse is, of course, well known from its inclusion in the American song The Arkansas Traveller (Roud 3756), although it predates that song by at least a century or two and was included in 17th century British humorous songs and stories. A menorca, by the way, is a variety of duck.

8. The Seeds of Love (Roud 3, Sharp 153)

Unknown singer. Balcombe, Sussex, 1974.

I sowed the seeds of love,

And I sowed them in the spring.

In April, May and June likewise,

While the small birds sweetly sing,

While the small birds sweetly sing.

My garden was planted well,

With flowers everywhere.

I had not the liberty of choosing for myself,

The flower I loved most dear.

The flower I loved most dear.

My gardener was standing by,

And I ask him to choose for me.

He chose me the violet, the lily and the pink.

And it's them I refused all three.

And it's them I refused all three.

The violet I did not like,

Because it doth fade away so soon.

The lily and the pink I did overlook,

I resolved to tarry till June.

I resolved to tarry till June.

In June there's the red rose bud,

And that's the flower for me.

I oftimes plucked at that red rose bud,

'Til I gained the willow tree.

'Til I gained the willow tree.

Now the willow tree will twist,

And the willow tree will twine.

I wish I was in that young man's arms

That stole away this heart of mine.

That stole away this heart of mine.

So a bunch of rue I'll wear,

That no one shall ever touch.

And I'll let the world so plainly see,

That I loved one flower too much.

That I loved one flower too much.

I was visiting the singer Harry Upton at his Balcombe, Sussex, home one day in 1974 when a neighbour arrived unexpectedly. 'Sing Mike that song you know', said Harry. So the lady did and I then asked her to sing it again so that I could record it. I wrote her name down in a notebook, which seems to have been lost in one of my several house-moves since then.

The Seeds of Love was, of course, the first song that Cecil Sharp noted. We are told that the song was written by a Mrs Fleetwood Habergham (d.1703), of Habergham, Lancashire, who, according to Dr Whitaker in his History of Whalley, was 'Ruined by the extravagance, and disgraced by the vices of her husband, she soothed her sorrows by some stanzas yet remembered among the old people of her neighbourhood.' It's a nice story, especially as I come from Whalley and remember borrowing Dr Whitaker's book from the local library when I was at the village school there, but there is no real evidence to suggest that Mrs Habergham did write the song.

Over the years the song has turned up repeatedly, usually with little textual or melodic variation. Both Catnach and Such printed the song in London, as did Sanderson in Edinburgh, Swindells in Manchester, Collard in Bristol, Taylor in Birmingham and Ward in Ledbury, and most English collectors have noted at least one version of the song. George Dunn's version can be heard on MTCD317-8, and Cyril Poacher of Suffolk sings a related piece, Plenty of Thyme, on MTCD303.

9. Poor Dog Tray (Roud 2668)

Packie Manus Byrne. Donegal, though living in London when this was recorded. 1975.

On the green banks of Shannon,

On the green banks of Shannon,

Where Sheelagh was nigh.

No blithe Irish lad

Was so happy as I.

No harp, like my own

Could so cheerfully play,

Wherever I went with

My poor dog Tray.

Poor dog he was faithful,

And kind to be sure.

He constantly loved me

Although I was poor.

And when sour-looking folks

Turned me heartless away,

I had always a friend

In my poor dog Tray.

When at last I was forced from

My Sheelagh to part.

She said, whilst this sorrow

Was deep in her heart,

'Remember your Sheelagh

When you're far, far away,

And be kind, my dear Pat,

To your poor dog Tray.

When the nights they were dark

And the winds blowing cold'

Pat and his dog

Were growing weary and old.

How snugly we slept

In our old coat of grey'

And he licked me through kindness

My poor dog Tray.

Though my wallet was scant

I remembered his kiss,

Nor refused my last crisp

To his pitiful face.

But he died at my feet

On a cold winter's day,

And I played a lament

For my poor dog Tray.

Where now can I go

Poor, forsaken and blind?

Can I find one to guide me

So faithful and kind?

To my own native village

So far, far away,

I can never return

With my poor dog Tray.

Poor Dog Tray was written by the Scottish poet Thomas Campbell (1777-1844), who was equally adept at writing 'Irish' songs. At least twenty English broadside printers issued the song, although I know of no versions collected in England prior to this recording. It appeared in Healy's Old Irish Street Ballads, vol 3. Campbell also wrote The Exile of Erin (Roud 4355) which was also popular with English printers.

10. The Mulberry Bush (Roud 7882)

Harry Cockerill. Askrigg, Yorkshire, 1972.

This is, of course, the tune to the children's game Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush. Robert Chambers (Popular Rhymes of Scotland. London & Edinburgh, 1870, p.134) prints a version under the title The Merry-Ma-Tanzie:

Another form of this game is only a kind of dance, in which the girls first join hands in a circle, and sing while moving round, to the tune of Nancy Dawson:

Here we go round the mulberry bush,

The mulberry bush, the mulberry bush;

Here we go round the mulberry bush,

And round the merry-ma-tanzie.

Chambers suggests that the phrase merry-ma-tanzie may be a corruption of the German Mit mir tanzen, which means Dance with me.

11. Jack and the Squire (Roud 511, Laws K40, Sharp 183)

Freda Palmer. Witney, Oxon, 1973.

Now Jack he heard the squire say,

Now Jack he heard the squire say,

That he that night with her would lay.

Chorus:

Da dum diddle um di do.

Da dum diddle um dee.

Now Jack he went and pulled the string,

And she came down and let him in.

But in the morn, when this fair maid awakened,

She looked at Jack with heart forsaken.

For Jack he had a ragged shirt,

His hands and face were covered in dirt.

'No', said Jack, 'it's no such thing,

For you came down and let me in.'

But Jack he loved the girl so well,

He told the squire to go to hell.

Freda could only remember a fragment of this song (the 5th verse, shown in italics, she remembered later), one that Cecil Sharp titled Jack the Jolly Tar. There are four versions printed in Sharp's collection, as well as a version, Doo me Ama, that was collected by Captain W B Whall and published in his book Ships, Sea Songs and Shanties (Glasgow, 1913, pp.23-24).

12. The Bonny Light Horseman (Roud 1185)

Jacquey Gabriel. Winchombe, Glos,1978.

All you maidens, wives and widows,

All you maidens, wives and widows,

I would have you pay attention;

For my very heart is aching,

Aching in its inmost core.

I'm a maiden that's distracted,

Broken- hearted I must wander,

For my bonny light horseman

Is slain in the wars.

Chorus:

Broken-hearted I wander,

Broken-hearted I wander.

For my bonny light horseman

Is slain in the wars.

Were I wing-ed like an eagle,

I would fly unto my darling.

To that spot so sad and lonely,

Where my true love he is lain.

I would kiss the grass above him,

For evermore I love him,

And I'll curse the wars so cruel,

That my true love has betrayed.

Like a dove I will go mourning,

For the loss of my own darling.

And no other man on this wide earth

My heart will ever gain.

In my grave so cold and cheerless,

Very soon I will be lying.

But my love and I in Heaven above,

Will surely meet again.

A song from the days of Waterloo. Numerous broadside printers issued it, including Catnach, Such, Goode, Fortey and Batchelor (all of London), Pearson and Swindells (both of Manchester), Fordyce (Newcastle-upon-Tyne), Cooper (Newcastle, Staffs.), Harkness (Preston) and Pratt of Birmingham. And at least two American printers issued it in their Forget-Me-Not Songsters. (Locke & Bubier of Boston c.1850 and Nafis & Cornish of New York in 1835). Some versions include verses relating to Napoleon Bonaparte - see, for example, the version in Terry Moylan's The Age of Revolution in the Irish Song Tradition 1776-1815 (Dublin, 2000, p.139).

13. The Doughty Packman (Roud 18306)

Ray Driscoll. Dulwich, London, 1989.

As I was going to Shrewsbury Town

As I was going to Shrewsbury Town

Right-fol, laity-o.

As I was going to Shrewsbury Town

Three jolly road robbers on me rode down,

With a right-fol-lol- lol laity-o.

I am but a packman out earning me bread,

For the three jolly robbers you'll soon be dead.

The first came in with a kick and a blow,

I gave him good buffet and laid him full low.

The next came in with a swing and a shout,

I up with me staff and I hit him about.

The next he cried, 'My brothers are slain.'

So I up with me staff and I served him the same.

I put the three wolves' heads in a bag,

And I set off to town on the robbers own nag.

At last at the Shire Reeve's house I came,

And asked for my bounty all in the King's name.

He hansled me full fifty pence,

Which I spent with a bawd and I took myself hence.

Now all you young fellow who road-robbers be,

Take care lest your packmen be doughty as me

Ray told me that he had learnt this when he was a young lad in Shropshire. Some schoolboys were singing it in the schoolyard and Ray learnt the song from them, though where the schoolboys got it from is anybody's guess. Did they learn it at school, in a class perhaps? And, if so, did they fully understand was the word bawd meant? I can find no other version of the song, although the tune is well-known from the song As I Was Going to Banbury that Cecil Sharp collected in Berkshire (Roud 2423, Sharp 326). The song could be very old (it certainly contains a number of ancient words), or it could equally be a Victorian/Edwardian attempt at creating a 'folk-song'.

14.The Holly and the Ivy (Roud 514, Sharp 353)

Ivor Hill & family. Bromsberrow Heath, Gloucestershire. 1980.

The holly and the ivy,

When they are both full-grown,

Of all the trees that are in the wood,

The holly bears the crown.

Chorus:

The rising of the sun,

And the running of the deer.

The playing of the merry organ,

Sweet singing in the choir.

The holly bears a blossom,

As white as the lily flower,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ,

To be our sweet Saviour.

The holly bears a berry,

As red as any blood,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ,

To do poor sinners good.

The holly bears a prickle,

As sharp as any thorn,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ,

On Christmas day in the morn.

The holly bears a bark,

As bitter as any gall,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

For to redeem us all.

In her Guide to English Folk Song Collections Margaret Dean Smith says that all the versions of this song appear to derive from a single source, namely a Birmingham broadside printed by Wadsworth c.1710. She also adds that, 'the holly-and-ivy metaphor of the male and female principle, well-known in mediaeval poetry, is rare in folksong, despite its continuing prevalence in active Christmas custom.' Some years ago Ewan MacColl tried to claim this as a 'pagan' carol by saying that the third line of the chorus should be, 'The playing of the merry old Gods', but, I think that Ewan was mis-hearing what was actually being sung.

15. Little by Little and Bit by Bit (Roud 10674)

Charlie Bridger. Stone-in-Oxney, Kent. 1984.

For fish I went fishing one summer's day,

When a man came along and to me did say:

'Can't you see that notice, it's plain and clear.

These waters are private, you can't fish here.'

Little by little and bit by bit,

I said, 'I'm not fishing, though here I sit.

I'm only just drowning my worm in it.'

Little by little and bit by bit.

When I was a policeman, some years ago,

I tackled some burglars, my pluck to show.

They pinched me, they punched me,

They pinched my change,

They then sat me down on the kitchen range.

Little by little and bit by bit,

Those bars got red hot just where I did sit.

But I got three big stripes on my…arm for it.

Little by little and bit by bit.

My wife doesn't sleep very well, and so

I sing her to sleep with the lights turned low.

There's only one song that brings her repose,

So I sing it to her till to sleep she goes.

Little by little and bit by bit,

I came home one night and I had a great fit.

For I found she was teaching the lodger it.

Little by little and bit by bit.

My wife through my pockets goes every night,

So I thought I would stop her little game alright.

I took my money to bed with me,

And in my shirt sewed my LSD.

Little by little and bit by bit,

In the morning I woke and what do you think?

For in the wife's nightgown I'd fastened it,

Little by little and bit by bit.

I'm unable to say who wrote this Music Hall piece, although it was recorded in 1908 by the Music Hall singer Sam Mayo (1875-1938) on Jumbo 199. The only other sighting seems to be from the singer Bob Mills of Winchester, who sang it to Paul Marsh c.1979. Bob's incomplete version was included on the cassette Songs of a Hampshire Man (People's Stage Tapes 05), which is now out-of-print, although Paul tells me that he may be reissuing the cassette on CD format.

16. I'll Sing of Martha (Roud 2467 & 10560)

Freda Palmer. Witney, Oxfordshire, 1974.

I'll sing of Martha, my dear wife,

Her loss I deeply mourn.

She's left this world of care and strife

And now I'm all forlorn.

She used to call me turtle dove,

To all my faults were blind.

I never can forget my love,

She was so good and kind.

So good and kind was Martha dear,

She'd let me scrub the floors,

And once she even let me clean

The knocker on the door.

She'd let me fetch her errands in,

And say I was a dear.

And once a week she'd let me have

An half a pint o beer.

The baby she would let me nurse,

And wash it now and then.

And never send me off to bed

'Til very nearly ten.

Our eldest boy is very tall,

His age is twenty-three.

Dear Martha saves his left-off clothes,

And cuts them down for me.

I never went out by myself,

She thought it was not right;

She'd take me every morn to work

And fetch me back at night.

Especially on a Saturday night

When I had got my pay,

She'd put it in her purse for fear

I might lose it on the way.

Oh, I can't forget my Martha dear,

I loved her so because,

She was so good and kind to me,

She was, she was, she was.

Written in 1885 by David G Day, as She Was! She Was! She Was! The Black-Country singer George Dunn said that the last verse of this song was sung as a 'circular' song by hop-pickers. George's short fragment, Oh, She was so Good and Kind to Me can be heard on his double CD Chainmaker (Musical Traditions MTCD317-8).

17. Dales Waltz

Harry Cockerill. Askrigg, Yorkshire, 1972.

Reg Hall suggests this is one multi-themed piece, which Harry may have got it from a record. 'But my guess is that its a local (perhaps his own) composition in the genre of yodel waltzes. He would have heard similar on the wireless and at the pictures. It's built on such a simple chord structure that it would compose itself as the player moves the bellows!'

18. A British Soldier's Grave (Roud 1223, Greig 110)

Archer Goode. Cheltenham, Glos, 1975.

The battle was over; the stars were shining bright,

The battle was over; the stars were shining bright,

The moon shone o'er the dying and the dead.

None could be heard, save the screams of the wild birds

As they fluttered round that dying soldier's head.

In his suit there lay one who'd nobly fought the day

And true to him, his comrade standing by.

As he in anguish cried, his comrade gently sighed,

And with his hand he wiped away a tear.

He whispered 'Goodbye' to his comrades so dear.

With his head upon his knapsack, gently lay.

'If you live to get home, you can tell them I am gone

And I'm lying in a British soldier's grave.

'Don't you remember that dear old oak tree?

With my knife I cut my name out in the bark.

And early in the morn when I reap the golden corn

And listen to the warbling of the lark.

'And that dear old country spot that will never be forgot

For that was where I used to meet the girl I loved.

Tell her not to cry, for I will meet her bye and bye

In that beautiful and happy land above.

'Tell my darling mother not to wait for me,

For in the battle I nobly took a part.

Break the news to her gently, my comrade.' he cried

'For I'm sure it will almost break her heart.

'Tell my only sister that I've kept this gift so rare,

That on parting she fondly gave to me.

Although now caressing, 'tis stained with my life's blood,

Dear comrade, this locket I'll give thee.'

He whispered 'Goodbye' to his comrades so dear.

With his head upon his knapsack, gently lay.

'If you live to get home, you can tell them I am gone

And I'm lying in a British soldier's grave.

'I feel that I am dying, my breath is going fast,

Raise me up dear comrade that I may see

The moon that gives us light and the watch-fires burning bright,

And our comrades as happy as can be.'

Then he heaved a sigh, and then fell back and died

Loved by all with hearts so gentle and so brave.

And at the break of day his corpse they gently laid

In a crude, but, a British soldier's grave.

Roy Palmer has traced a broadside of this song to the printer F Jones, of 55, Lamaert Street, Sheffield, who was working at the address during the period 1894-98. The song could, of course, predate this period. As ever, Britain was fighting in various parts of the Empire at that time and there are plenty of battlefields that could have provided the inspiration for the song. Gavin Greig seems to have been the only collector to note down the song, and there are two versions in his collection.

19. Billy Brown (Roud 3354)

Freda Palmer, Witney, Oxon, 1974.

Billy Brown was a worn-out clown

And a careful clown was he.

He'd saved enough to open a pub,

Somewhere in Kensal Green.

You never could forget the tricks

By which he earned his daily bread,

And now and then, when the fit came on,

He'd stand upon his head.

All the people shouted out, 'Oh, my'.

All the people they did stare.

For there was Brown, he was upside down,

With his legs sticking up in the air.

Now the nearest neighbour to old Brown,

Was a widow, Mrs Birch.

He proposed to her. She answered 'Yes',

So they toddled off to church.

'Will you love and obey this man?'

The worldly parson said.

She blushed and screamed, for there was Brown

A-standing on his head.

The parson gave a scream, and shouted out 'Oh, my'

And all the people they did stare;

For there was Brown, he was upside down,

With his legs sticking up in the air.

A-twelve month after a child was born,

To the great delight of Brown.

It was the image of himself

And a regular little clown.

Before the child was six weeks old

It scrambled out of bed,

And to the nurse's great surprise

Was standing on his head.

The nurse she gave a scream and shouted out 'Oh, my'

As she fainted away in the chair;

For there was young Brown, he was upside down,

With his legs sticking up in the air.

Arthur Howard, of Hazlehead, Yorkshire, sang this as Old Jepson Brown on the LP Merry Mountain Child (Hill & Dale HD 006). The song is clearly from the Music Halls, where singer Harry Fragson recorded a song called Billy Brown of London Town in 1909 (issued on either Pathe 5104 or 5333) which is likely to be the same song, and Will Bint sang Brown Upside Down, which almost certainly is - although it could equally, I suppose, be another title for The Old Dun Cow.

20. The Old Drunken Man (Roud 114, Child 274, Greig 1460, Sharp 39)

Alice Francombe, Cam, Dursley, Glos, 1980.

Late home came I one night,

And late home came I,

And o'er there on my table

Another man's hat did lie.

'Whose hat is this, my love,

Or whose might it be?'

'My love it is a band-box

Your mother have left for thee.'

'Oh, I have travelled,

Ten thousand miles or more,

But never have seen a band-box

With ribbon round before.'

Late home came I one night,

And late home came I,

And o'er there on my door

Another man's coat did lie.

'Whose coat is this, my love,

Or whose might it be?'

'My love it is a blanket

Your mother have left for thee.'

'Oh, I have travelled,

Ten thousand miles or more,

But never have seen a blanket

With button-holes down before.'

Late home came I one night,

And late home came I,

And o'er there in my corner

Another man's stick did lie.

'Whose stick is this, my love,

Or whose might it be?'

'My love it is a poker

Your mother have left for thee.'

'Oh, I have travelled,

Ten thousand miles or more,

But never have seen a poker

With notches down before.'

Late home came I one night,

And late home came I,

And o'er there by the bed

Another man's boots did lie.

'Whose boots is this, my love,

Or whose might it be?'

'My love it is coal-boxes

Thy mother have left for thee.'

'Oh, I have travelled,

Ten thousand miles or more,

But never have seen coal-boxes

With lace-holes down before.'

Late home came I one night,

And late home came I,

And o'er there in my bed

Another man did lie.

'What man is this, my love,

Or who might it be?'

'My love it is a baby

Thy mother have left for thee.'

'Oh, I have travelled,

Ten thousand miles or more,

But never have seen a baby's face

With whiskers round before.'

Versions of this well-known ballad are found all over Europe. The story seems simple enough. A man returns home to find another man's horse, dog, boots etc, where his own should be. There follows a formulaic exchange between the man and his wife, who explains that her husband's eyes are deceiving him, and the story ends without rancour, revenge or remorse. It's a bit of a joke, to be sung in the pub on a Saturday night, although a version collected from George Spicer of Sussex ends with the spoken comment, 'I stayed home Saturday night!' And yet, there seems to be something unsaid. A L Lloyd, quoting the Hungarian folklorist Lajos Vargyas, mentions a possible connection between this ballad and one from Hungary, Barcsai (which has parallel versions in the Balkans, France and Spain). Here a couple are caught in an adulterous act by a returning husband, who promptly kills both his rival and his wife. There are even Mongol versions of Barcsai, so who can say where the story really come from?

George Spicer's version is available on the Topic CD They Ordered their Pints of Beer and Bottles of Sherry (TSCD663) and the Mainer Family from North Carolina sing an American version on Voices from the American South (Rounder CD 1701). This is one of the few Child ballads to have entered the Black American musical tradition - see, for example, Cat Man Blues by Blind Boy Fuller (Document DOCD 5091 & 5092), or Blind Lemon Jefferson's Cat Man Blues (JSP 7706D).

21. Feyther Stole the Parson's Sheep (Roud 2498, Greig 309)

George Fradley and Tufty Swift (melodeon). Sudbury, Derbyshire, 1984.

There was a little boy walking down the street one day and he was singing at the top of his voice … this is what he was singing …

There was a little boy walking down the street one day and he was singing at the top of his voice … this is what he was singing …

Me feyther stole the Parson's sheep,

And a merry Christmas we will keep.

Me feyther stole the parson's sheep,

And I'll say nowt abaat it.

And I'll say nowt abaat it.

Well…he was…he was overheard by the church warden and this church warden said to him, 'Hey John come here.' He said, 'Will you come to church on Sunday morning and sing that song for us?' He says, 'Well, I can't come (to) church.' He says, 'I've got no clothes. I've got no Sunday clothes to come in.' 'If you'll come and sing that song I'll give you a suit of clothes.' So, er, 'All right!' So, er, he went home, told his dad. 'Ee,' dad said, 'you mustn't sing that.' He says, 'You'll have me sent quod.' And, er, little boy thought to hisself, 'Alright, then'. And he was thinking about his new suit of clothes. Anyway, Sunday come and by that time he'd got his new suit, new pair of shoes, and a hat…and off he went to church. It was something different for him. Anyway, during a certain time… during the service the parson said, 'Now, ladies and gentlemen I'm going to call on a little boy to sing a song and I want you to take note of everything he says, because it is the truth. Anyway… 'Come on, Johnny' and Johnny went up and he started … He says:

As I was walking out one day,

Parson Green was rather gay.

He was romping Molly on the hay,

And he tippled (dippled?) her upside down, sir.

And he tippled (dippled?) her upside down, sir.

He said, 'Was his face red!' He said it was the truth, didn't he.

quod = prison.

Several 19th century broadside printers issued this cante-fable, under the title Parson Brown's Sheep. Fortey, Such, Johnson and Ryle issued the song in London, while Harkness of Preston, Pearson of Manchester and Sanderson of Edinburgh also included it on their respective sheets. According to the English folktale scholar Katharine Briggs, The Parson's Sheep 'is scattered throughout Europe.' It is listed as type 1735A in A Aarne's Types of the Folktale (Helsinki, 1961) and Stith Thompson assigns it motif K1631 in his monumental Motif Index (Bloomington, Indiana. 1955). English song collectors such as Ralph Vaughan Williams and George Gardiner noted versions at the beginning of the 20th century. In Scotland the tale exists as a song, The Minister's Wedder, and as a cante-fable. See the version in Scottish Traditional Tales (Edinburgh, 1994) by Bruford & MacDonald, for an example of the latter from Orkney.

22. The Oyster Girl

Harry Cockerill. Askrigg, Yorkshire, 1972.

This is quite a popular and well-known tune. There are a number of songs bearing the title, the best known being the one sung by singers such as Phil Tanner (Veteran VT145CD) and George Dunn (MTCD317-8) - which is listed as Roud 875 and Laws Q13. The present tune probably comes from one of the other Oyster Girl songs that was printed on Victorian broadsides. Arthur Marshall, a Yorkshire melodeon player, can be heard playing his version of The Oyster Girl on the Topic CD Ranting & Reeling - Dance Music from the North of England (TSCD669).

23. Johnny o' Hazelgreen (Roud 250, Child 293)

Packie Manus Byrne. Donegal, though living in Manchester when this was recorded. 1964.

One night as I rode o'er the lea,

With moonlight shining clear;

I overheard a fair young maid,

Lamenting for her dear.

She did cry as I drew nigh,

The better it might have been;

For she was letting the tears roll down,

For Johnny o' Hazelgreen.

'What is your trouble, my lovely maid,

Or what caused you to roam?

Is it your father or mother that's dead,

Or have you got no home?'

'My parents they are both alive,

And plainly to be seen;

But I have lost my own true love,

Called Johnny o' Hazlegreen.'

'What sort of boy is your Hazelgreen?

He's one I do not know.

He must be a braw young lad,

Because you love him so.'

'His arms are long, his shoulders broad,

He's comely to be seen,

And his hair is rolled like chains of gold,

He's Johnny o' Hazlegreen.'

'Dry up your tears my lovely maid,

And come along with me.

I'll have you wed to my only son,

I never had one but he.

Then you might be a bride,' I said,

'To any Lord or King.'

'But I'd far rather be a bride,' said she,

'To Johnny o' Hazlegreen.'

'She got on her milk-white steed,

And I got on my bay.

We rode along that moonlight night,

And part of the next day.

When we came up to the gate,

The bells began to ring.

And who stepped out but the noble knight,

They called Johnny o' Hazelgreen.

'You're welcome home, dear father' he said.

'You're welcome home to me.

You've brought me back my fair young maid,

I thought I'd never see.'

The smile upon her gentle face,

As sweet as grass is green.

So I hope she's enjoying her married life,

With Johnny o' Hazlegreen.

When I first got to know Packie he asked me to record some of his whistle tunes so that he could send a tape to a relative in Canada. Accordingly, he came round to my home one evening and we recorded the tunes. I had been reading Evelyn Wells' book The Ballad Tree at the time and, knowing that Packie knew some songs, I followed Evelyn's advice and asked Packie if he knew the one 'about the milk-white steed'. 'God, yes.' He said. 'But I haven't sung that in years.' I switched on the tape machine and Packie's sang me a version of Johnny o'Hazelgreen. It was possibly the first version to come from an Irish singer and I was just about knocked out. This is that early recording, and not the one that appeared on Packie's Topic LP Songs of a Donegal Man (12TS257).

Professor Child included five Scottish versions of Johnny o Hazelgreen in his collection, all of which date from the early part of the 19th century and, in the form rewritten by Sir Walter Scott, the ballad has proven especially popular in Scotland. Versions have also turned up in North America. Packie believes that the ballad was taken to Donegal by his grand-uncle, who had learnt it whilst working in Scotland, and who had taught the song to Packie's aunt, 'Big' Bridget Sweeney of Meenagolin, County Donegal, who in turn taught it to Packie.

24. Nowt to do wi' Me (Roud 5315)

George Fradley & Tufty Swift (melodeon). Sudbury, Derbyshire, 1984.

Some folks are always talking,

Of other folk's affairs,

I think it would be better

If they'd concentrate on theirs.

They talk of where they're going,

Or of whom they're going to see,

But let other folk do what they like,

That's nowt to do wi' me.

Cause I never interfere wherever I may be,

Let other folks do what they like,

That's nowt to do wi' me.

Mrs Green, our next door neighbour,

She's lodgers four or five,

To make a tidy job of it

I'm sure she does contrive.

And now they all complain and say

That they'll lose their LSD.

But whether she gets it or not,

That's nowt to do wi' me.

There's Mr Jones, the bobby,

He's dressed so very fine,

His wage is only eighteen bob

While mine is twenty-nine.

He wears a great gold watch and chain

And wins one, two, or three,

But ... where the deuce he get's 'em from,

That's nowt to do wi' me.

There is a smart young lady,

Her age is twenty-four;

She wed a fine old gentleman

Of ninety-five or more.

Just lately they've been blessed with a son

And the old man's filled with glee,

They say it's not much like him,

But that's nowt to do wi' me.

The Queen come up from London

It was on a summer's day,

The little brids were singing

And the kids were all so gay.

The object of her visit was

For her to come and plant a tree,

But if her set it right road up or not,

That's nowt to do wi' me.

There's Mr Edgar Merry,

He sells mutton, beef and pork;

His beef is always tender

You can cut it with a fork.

And now with the rising prices,

'A pound, a pound', they say.

But if he's out to make his fortune quick,

That's nowt to do wi' me.

Nothing to Do with Me was printed on a broadside by Sanderson of Edinburgh. I only know of one other recording, by Bill House of Beaminster, Dorset. Bill had the song from his father, George House, who sang songs to the Edwardian collectors Robert & Henry Hammond. Bill's version appeared on the cassette Gin and Ale and Whiskey that was issued by Nick Dow in 1985. Edgar Merry, who is mentioned in the final stanza, was a one-time neighbour of George Fradley.

25. What is the Life of a Man (Roud 848)

Archer Goode. Cheltenham, Glos, 1975.

As I was out walking one morning at my ease,

A-viewing the leaves as they fell from the trees,

They were all in full motion, appearing to be,

And those that were withered; they fell from the trees.

Chorus:

What is the life of a man, any more than the leaves?

A man has his season - so why should he grieve?

Although for a time, he appears blythe and gay,

Like the leaves, he must wither and soon fade away.

Now don't you remember, a short while ago,

The leaves were in full motion, apparently so,

A frost came upon them, and withered them on (up?)

A rain came upon them - and down they did drop.

Chorus.

If you go in yonder churchyard, many names there you will find,

Old friends have left this wide world, like leaves in the wind,

Old age and affliction on them it did call,

And those that were withered, oh, down they did fall.

Chorus.

The following lines, from a blackletter broadside of c.1570, are typical of a period when the Church controlled all things moral. If you lived a good life on earth, then you would go to Heaven. If not, then the doors of Hell were beckoning.

Young Men, remember! Delights are but vain,

And after sweet pleasure comes sorrow and pain.

Writing about this period, Tessa Watts says, 'The memento mori ballads were based on the assumption ... that ordinary people could turn the objects of daily life into visual allegories for death and the world beyond.' (Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550 - 1640. Cambridge, 1991. p.138.) Plants, especially flowers, were extremely popular in this respect.

The life of a man it is but a span,

It's like a morning flower;

We're here today, tomorrow we're gone,

We're dead all in one hour.

(from The Moon Shines Bright collected by Cecil Sharp from Mrs Gentie Phillips of Birmingham. 26.9.1910).

It was the Greek poet Homer, however, who first compared man's death to the fall of the leaf. 'As leaves on trees, such is the life of man', and several blackletter broadsides are based on this idea. Our present song, however, probabaly began life in the early 1800's when it was printed, as The Fall of the Leaf, by a handful of northern broadside printers, including Sanderson (Edinburgh), Ross and Walker (both of Newcastle), Stewart (Carlisle), Dalton (York) and Harkness (Preston). Surprisingly, most collected sets have come from the south-east of England. These include versions by George Townshend (Musical Traditions MTCD304) and Harry Holman (MTCD 309-10).

26. Wassail Song (Roud 209. Sharp 373)

Alice Francombe, Cam, Dursley, Glos.1980.

Waissail, waissail, all over the town,

Our bread it is white and our ale it is brown.

Our bowl it is made of the maypole and tree,

And a wassailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Drink unto thee, drink unto thee,

Our waissailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Now here's to the ox and its too long tail,

May God send our master a fine keg of ale.

A fine keg of ale as we may all see,

And a waissailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Now here's to the ox and to its hind leg,

May God send our master a fine christmas peg.

And a fine christmas peg as we may all see,

And a wassailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

And here's to the ox and to its long horn,

May God send our master a fine crop of corn.

A fine crop of corn as we may all see,

And a waissailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Drink unto thee, drink unto thee,

Our waissailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Now here's to the ox and to its right eye,

May God send our Mrs a fine christmas pie.

A fine christmas pie that we may all see,

And a wassailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Drink unto thee, drink unto thee,

Our waissailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Now here's to the ox and to its right ear,

May God send our master a happy new year.

A happy new year that we may all see,

And a wassailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Drink unto thee, drink unto thee,

Our wassailing bowl we'll drink unto thee.

Now, Landlord, come fill us a bowl of your best.

We hope that Christ's sake in heaven will bless.

But if you should fill us a bowl of your small,

Then down shall go landlord, bowl and all.

'The midwinter carolling custom', according to A L Lloyd, 'is very ancient. We know it existed in ancient Greece. And today from western Europe to the Balkans it still persists, whether the songs have pagan or Christian words, and whether the singers are in disguise or not.' (Folk Song in England. London, 1967). Cecil Sharp collected no fewer than twenty-seven versions, many of which are echoes from olden times. Take, for example, the set from Bratton in Somerset. 'The wassailers used to meet in the orchard about seven or eight o'clock in the evening, join hands, and dance in a ring round an apple tree singing the song. At the conclusion they stamped on the ground, fired off their guns, and made as much noise as they could while they shouted in unison the words appended to the song. Having placed some pieces of toast soaked in cider on one of the branches, they proceeded to another tree, around which they repeated the ceremony. When Cecil Sharp asked the singer what happened to the toast, he replied: "All gone in the morning; some say the birds eat it, but…" (Cecil Sharp's Collection of English Folk Songs edited by Maud Karpeles. London, 1974. Volume 2, p.635).

Alice Francombe's text combines both Christian and Pagan elements and has God and Christ rubbing shoulders with the ritual ox, a descendant of both the sacred Apis Bull of Egypt and the Bull Kings of ancient Turkey and Greece.

Three wassailing songs are included on the Topic CD You Lazy Lot of Bone Shakers (TSCD666) and another version that I collected in Gloucestershire will soon be issued by Veteran Records.

27. Barbara Allen (Roud 54, Child 84, Sharp 29)

Debbie and Pennie Davis. Near the Northfields housing estate, Tewkesbury, Glos.

In Scarlet Town where I was born,

There was a fair maid dwelling,

And all the lads cried 'Well-a-day'

For love of Barbara Allen.

Look over, look over to yonder hill,

You'll see some cows a-feeding,

For they are mine, they are left for thine,

They are left for Barbara Allen.

Look down, look down to the foot of my bed,

You'll see a waistcoat hanging,

And in the pocket a watch and chain,

It's left for Barbara Allen.

Look down, look down to the foot of my bed,

You'll see a basin standing,

A basin of blood from my heart has shed,

It's left for Barbara Allen.

Oh, mother dear make me a bed,

Make it soft and narrow.

For Johnny died/dies for me today,

I'll die for him tomorrow.

Oh, parson dear, dig me a grave,

Dig it deep and narrow,

And on my bosom place a red rose,

For Johnny's a sweet briar.

They grew and grew to the top of the church,

'Til they couldn't grow any higher'

They turned back down in a true love knot,

The rose around the briar.

This has to be the ubiquitous ballad, with versions turning up all over the English-speaking world. The two singers, granddaughters of gypsy singers, learned the piece from their mother who, in turn, had picked it up from her mother. Their style of singing, however, is totally different from the way their grandparents sang and has probably been influenced by listening to recordings of Country & Western singers. It has been suggested to me that the girls actually learnt the song from a Country & Western recording, but this is not the case.

Barbara Allen was first mentioned by Samuel Pepys in his diary entry for January 2, 1666, when he said that he was pleased to hear Mrs Knipp (an actress) singing her little Scotch song of Barbary Allen, and some scholars have interpreted Pepys' comment as meaning that the song originated on the stage. Others, probably with less evidence, have suggested that that the song was originally a libel against Charles II and his mistress Barbara Villiers.

Steve Roud lists over 170 recordings, including versions from Texas Gladden (Rounder CD 1800),Fred Jordan (Veteran VTD148CD), Phil Tanner (Veteran VT145CD), Joe Heaney (Topic TSCD518D), Garrett & Norah Arwood (Musical Traditions MTCD323-4) and Jim Wilson (Musical Traditions MTCD309-10). The Library of Congress previously issued a full LP - Versions and Variants of the Tunes of Barbara Allen (AAFS L54) - devoted to this single ballad.

For some reason, the girls' surname was wrongly given as Harris in the notes to the Topic LP where this recording first appeared.

Acknowledgements:

Firstly, my thanks to all the performers and their families. On a number of my collecting trips I was accompanied by other enthusiasts and I would especially like to thank John Browell, Gwilym Davies, John Howson, Ken Langsbury, Ken Stubbs, Tufty Swift and Andy Turner who helped out with some of the recordings heard on this CD. I would also like to thank Malcolm Taylor, of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, and Roy Palmer, my colleague on the editorial Board of the Folk Music Journal, for help in identifying some of the songs.

Credits:

All these recordings were made, many of the photos were taken, and the introduction, transcriptions and song notes were written, by Mike Yates. My sincere thanks to Mike and to everyone else who has contributed their time and expertise so willingly:

• Doc Rowe, Brian Shuel, Jacquey Gabriel, Derek Schofield - for other photos.

• Roy Palmer - for the broadside example.

• Danny Stradling - for proof-reading.

• Steve Roud - for providing both MT and Mike Yates with a copy of his Folk Song Index, whence came some of the historical information on the songs. Also for help with finding songs and allocating Roud numbers to new entrants to the Index.

• Clare Gilliam and the BLSA - the complete Yates Collection of original pre-2000 recordings are now housed in the British Library Sound Archive. All the recordings used here are taken from digital transfers of those originals, done by Clare at the BLSA and funded by the National Folk Music Fund.

Booklet: editing, DTP, printing

CD: editing, formatting, production

by Rod Stradling

A Musical Traditions Records production © 2004

[Track Lists]

[Introduction]

[The Performers]

[The Songs]

[The CD]

[Credits]

Article MT143

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 8.9.04

As I walked out one morning,

As I walked out one morning,

originally issued on a 78 rpm disc, can be heard on another Topic album - Come All My Lads that Follow the Plough (Topic TSCD655). There is also a recording by Tony Harvey of Suffolk on the Veteran CD Songs Sung in Suffolk (VTC2CD).

originally issued on a 78 rpm disc, can be heard on another Topic album - Come All My Lads that Follow the Plough (Topic TSCD655). There is also a recording by Tony Harvey of Suffolk on the Veteran CD Songs Sung in Suffolk (VTC2CD).

Chorus:

Chorus: 'Where have you been all day, Henry my son?

'Where have you been all day, Henry my son? On the green banks of Shannon,

On the green banks of Shannon, Now Jack he heard the squire say,

Now Jack he heard the squire say, All you maidens, wives and widows,

All you maidens, wives and widows, As I was going to Shrewsbury Town

As I was going to Shrewsbury Town The battle was over; the stars were shining bright,

The battle was over; the stars were shining bright, There was a little boy walking down the street one day and he was singing at the top of his voice … this is what he was singing …

There was a little boy walking down the street one day and he was singing at the top of his voice … this is what he was singing …