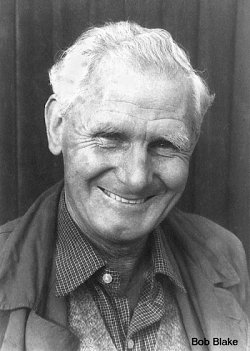

This short article was written a couple of years ago, though updated recently. It has remained, unpublished, on my computer for a number of reasons, the chief of which is the chance that some readers could misinterpret my reasons for writing the piece in the first place. Basically, the article concerns the Sussex singer Bob Blake, whom I met and recorded in the early 1970s. When we first met I assumed that Bob was a traditional singer, similar to the other Sussex singers, such as George Spicer and Harry Upton, that I was recording at the same time. Following Bob's death, his daughter sent me some manuscripts which indicated that Bob, unlike George and Harry, had learnt all of his songs from printed sources and that I, in my naïveté, had unwittingly helped to present Bob as a 'traditional folk singer, rather than as a singer of traditional songs. I cannot stress enough that this article is not meant as a condemnation of Bob Blake, a charming and generous man, but rather is meant to be a re-evaluation of Bob, his songs and my approach to him. It is as much a critique of myself as it is of Bob.Writing in his new book, Victorian Songhunters, E David Gregory has this to say about the word folksong:Mike Yates

The term folksong is problematic, in part because there is no consensus on how to define it, and in part because it has been claimed that the concept is an ideological construction and that most or all folksongs are in fact fakesongs (i.e., either composed songs masquerading as folksongs or traditional songs modified by their middle-class collectors).Gregory then goes on to offer various definitions of the word, most of which 'assume that folksong is traditionally a form of lower-class music, i.e., that it is in some sense a music of ordinary people and not that of professional musicians, the highly educated, or wealthy members of the middle or upper classes.'1

The source of the expressive culture which folksong collectors wished to see more fully appreciated, however, did have certain problematic implications. It comprehended modal music with impressive historical and cultural associations and had notable academic and artistic possibilities. It existed, however, almost entirely in the performance of the semi-literate working class. This apparent paradox was explained in terms which both reinforced the status of the music whilst distancing it from its performers. It was proposed that generally, traditional art forms, especially narrative and music, did not originate with the 'folk', but in fact derived from a gesunkenes Kulturgut (sic) of materials created by the upper classes. These aesthetically superior creations had then, over time, been passed on to or adopted by the lower class folk.Another problematical term is the word folksinger, though here Dr Gregory remains silent when it comes to definitions. And he is not alone in this matter. Very few scholars, it seems, have bothered to spend their time defining who is, or who is not, a folksinger. It seemed to be that if you sang a folksong, then you were a folksinger. At one time we all knew that traditional singers had learnt their songs at their mother's knee, whilst revival singers had come to folk music via books and records. Things changed for me in 1964 when I happened to see a copy of Lucy Broadwood's English County Songs jutting out from underneath Fred Jordan's bed. 'Hang on,' I thought. 'Fred's a traditional singer. So why does he have a copy of a song book under his bed?' The answer, of course, is that singers, traditional or otherwise, pick up songs wherever they can. It might worry a scholar where a song comes from, but, to a singer, a good song is a good song.3

Something else happened in 1964 that made me change my fledgling ideas about just what it was that made a singer a folksinger. Tony Wales, then running the Folk Shop at Cecil Sharp House, invited me down to that year's annual Horsham Folk Day. The event was held on a Saturday and I was quite knocked out when I realised just how many fine singers there were left in Sussex. One singer, and an excellent one at that, was a bee-keeper by the name of Bob Blake, and I remember him singing The Grey Hawk on that occasion. There was, I recalled, something distinctly odd about the tune, which changed key somewhere in the middle of the verse, before returning to the original key in the last line. At the time I had never heard of the term modulation and was unaware that English singers did not usually do such things. The following year I moved north to live in Manchester and it was to be almost ten years before I met Bob again. I was then living in Biggin Hill, Kent, and was looking for traditional singers to record for a series of LP's that Topic Records wished to issue.

Something else happened in 1964 that made me change my fledgling ideas about just what it was that made a singer a folksinger. Tony Wales, then running the Folk Shop at Cecil Sharp House, invited me down to that year's annual Horsham Folk Day. The event was held on a Saturday and I was quite knocked out when I realised just how many fine singers there were left in Sussex. One singer, and an excellent one at that, was a bee-keeper by the name of Bob Blake, and I remember him singing The Grey Hawk on that occasion. There was, I recalled, something distinctly odd about the tune, which changed key somewhere in the middle of the verse, before returning to the original key in the last line. At the time I had never heard of the term modulation and was unaware that English singers did not usually do such things. The following year I moved north to live in Manchester and it was to be almost ten years before I met Bob again. I was then living in Biggin Hill, Kent, and was looking for traditional singers to record for a series of LP's that Topic Records wished to issue.

Bob lived with his wife in a country cottage and, while willing to sing and record, was extremely quiet and reserved. He had little to say about his life and even less to say about his songs. He did tell me that he had picked up The Grey Hawk in 'the west-country' in the 1930s whilst on a cycling holiday. His father, a former sailor, had taught him some sea shanties and a couple of other songs came from an uncle (his father's brother) who farmed in Gloucestershire. Bob, it seems, would visit the uncle during school holidays and it was there that he learnt We Shepherds are the Best of Men and Our Sheepshearing's Done. At least, that's what I thought he said at the time. Rechecking my notes I find that Bob did not exactly say that he had learnt these songs from his uncle. Rather, he implied that he had learnt these songs from his uncle by saying that his uncle was a singer who 'knew a number of songs such as We Shepherds are the Best of Men and Our Sheepshearing's Done'. Of John Barleycorn he had nothing to say, beyond that he had known it 'for a long time'. Bob did tell me that he had been born in south London and had moved to Sussex when he was 'young'. But that, really, was all that he had to say about himself and his songs. To be honest, I have to say that I liked Bob and was completely won over by his gentle charm and fine singing. In the notes to the album Up in the North and Down in the South![]() 7 I said that Bob was, 'an immensely likeable man (who) was nevertheless extremely shy.' I also said that, 'I never felt that he was totally relaxed in my presence.' On one occasion I mentioned to Peter Kennedy that I knew Bob and was surprised to find that Peter did not share my enthusiasm for Bob's singing. It never entered my mind that Peter may have known something about Bob that was unknown to me.

7 I said that Bob was, 'an immensely likeable man (who) was nevertheless extremely shy.' I also said that, 'I never felt that he was totally relaxed in my presence.' On one occasion I mentioned to Peter Kennedy that I knew Bob and was surprised to find that Peter did not share my enthusiasm for Bob's singing. It never entered my mind that Peter may have known something about Bob that was unknown to me.

In fact Bob Blake was born in Tooting, south London, in 1908, and did not move to Sussex until he was nineteen years old. He had trained as a leather trimmer and found work repairing vehicle upholstery in a Horsham garage. To start with he lodged with an elderly couple at a farm outside Horsham and he would cycle to work each day from the farm. Bob fell in love with the countryside, and with a local girl, and soon made Sussex his permanent home. If we accept what little Bob said, then he was already a traditional folksinger when he arrived in Sussex, having learnt songs from his father and uncle. (Or, at least, having implied that he had learnt songs from members of his family.) But, it may be that this was not quite true. It may be that Bob's stories of learning songs at home and in Gloucestershire were not exactly accurate and that, possibly hearing traditional singing in Sussex and not knowing any songs himself, he felt that he would like to be able to join in. But where could he find some of his own songs? I don't know whether or not Bob made a conscious decision to 'become' a folksinger. I doubt if he set out to deceive anybody when he moved to Sussex. Perhaps he just wanted to have a few songs of his own that he could sing in the pubs when there were other singers around. After all, he never claimed to be a traditional folksinger. He was a singer of old songs who, when approached by people like myself, retired behind his apparent shyness. And, if I wanted to see him as a traditional folksinger, then that seems to have been fine by him.

When I first met Bob I was quite happy to accept what he said, even though he did not offer too much by way of explanation as to where his songs came from. As I started to record some of his songs I did begin to wonder just why Bob was so unwilling to talk about the songs, and why he seemed nervous when I asked him about them. Seeking out other versions of The Grey Hawk I was surprised to find how similar Bob's set was to a version collected in 1905 from Robert Barrett of Puddletown in Dorset - a version that had been printed in A Dorset Book of Folk Songs by Brocklebank & Kindesley (London, 1948).![]() 8 I was also surprised to find that 'his uncle's' two shepherding songs were both printed in Lucy Broadwood's English County Songs - the very same book that Fred Jordan had once owned. And things may have stayed there, had it not been for the fact that Bob's daughter kindly contacted me following Bob's death asking me whether or not I was interested in seeing some song manuscripts that her father had compiled during his life. Of course I said 'Yes' and the collection, comprising some notebooks and a few loose sheets, soon arrived through the post. Much of the material had been written by Bob, although some of the loose sheets were in different handwritings and, as some included dedications such as 'To Bob', we may surmise that these were song texts given to Bob by other people.

8 I was also surprised to find that 'his uncle's' two shepherding songs were both printed in Lucy Broadwood's English County Songs - the very same book that Fred Jordan had once owned. And things may have stayed there, had it not been for the fact that Bob's daughter kindly contacted me following Bob's death asking me whether or not I was interested in seeing some song manuscripts that her father had compiled during his life. Of course I said 'Yes' and the collection, comprising some notebooks and a few loose sheets, soon arrived through the post. Much of the material had been written by Bob, although some of the loose sheets were in different handwritings and, as some included dedications such as 'To Bob', we may surmise that these were song texts given to Bob by other people.

To begin with there was a small notebook which contained a listing of song titles. These were divided into four groups: 'Country', 'Sea', 'General' and 'Australian'. I would suggest that these were the titles of songs that Bob liked to sing and that the notebook was carried to remind him of song titles when he was out singing. The titles were as follows:

CountryMany of the other sheets and books contained songs and music from named sources. For example eight songs, The Ploughboy, The Dumb Wife, Guy Fawkes, The Kerry Recruit, The Jolly Waggoner, Gossip Joan, The Ringers of Egloshale and a Wassail Song, were copied from the 1963 edition of volume 2 of The Oxford Song Book. There were nine songs copied from Broadwood's English County Songs.

Our Sheepshearings done

We shepherds are the best of men

Crafty Ploughboy

I likes a drop of Good Beer

Basket of Eggs

John Barleycorn (Gloucester)

John .. .. (Sussex)

Fare thee well my dearest dear

Grey Hawk

Marrian went to Mill (French)

Crabfish

I'll tell you of a fellow

Loyal Lover

Through all the country round

Nightingale

Sun was just setting

Little red fox (Irish)

(I've travelled about a bit in my time) - this title is scored through.

I have been travelling

My father died

Dorsetshire George

Devil & Ploughman

West Country band

(I'll weave my love a garland) - this title is scored through.

Lord Thomas

Deserter from Kent

Sea

Chinese Bum boat Man

Tom Bowline

Crocodile

North Pole (Whaling)

Lanagaro Log

Blow ye Winds

Gallant Frigate Amphritite

Pretty Ploughing Boy

Oyster girl

Tinker & Tailor

Fiddlers Green

Nursing Mother

Heave away my Johnies

General

Linden Lee

Ferry ahoy

Who is Sylvie

Londonderry Air

Drink to me only

Simon the cellarer

Butlins

McPhersons Lament

Australian

Bishop & Bullocky

Overlander

Come all you jolly Drovers

In the year 58

These were Adam & Eve, The Loyal Lover, The Crocodile, Turmut Hoeing, I'll Tell You of a Fellow,

These were Adam & Eve, The Loyal Lover, The Crocodile, Turmut Hoeing, I'll Tell You of a Fellow,Now, it may be that, in some cases, Bob was writing out other versions of songs that he already knew, although I find this unlikely, and I am left with the conclusion that Bob probably learnt most, if not all, of his songs from print. The mention of two versions of the song John Barleycorn (one from Gloucestershire, the other from Sussex) is also a bit of a give-away, as Edwardian collectors often emphasised which part of Britain a song came from when they published their collections.

Over the years some people have take the line that the English folksong tradition is an oral tradition, forgetting, in the process, all those thousands of broadsides that were published and sold to generations of singers. Others have argued that this has not always been the case and that the importance lies in where and why singers were singing their songs. And, I suppose, some would ask whether or not all this really matters. My own view is that the tradition of singing English folksongs is, and always has been, a far more complex situation than people like Cecil Sharp and Lucy Broadwood liked to imagine. And the same could also be said for singing in Scotland. In 1956 the late Hamish Henderson was directed to a singer called Willie Mitchell who lived in Campbeltown on the Mull of Kintyre. Willie was a butcher by profession and a singer by inclination. He was also an amateur song-collector who noted songs from his friends and neighbours so that he, and his family, could sing the songs. According to Hamish:

In December, 1956, at his home in Smith Drive, Campbeltown, I found Willie Mitchell - a relaxed, friendly, obviously very fit wee man; a face full of humour and sympathetic intelligence, and with that familiar ruddy sheen which seems the cachetic birthright of all butchers. His charming family (wife Agnes, and daughters Agnes, Mary and Catherine) all seemed to share his enthusiasms in full measure … He showed me his manuscript song-book, which he had started in 1945, and it proved to be an exemplary - and quite fascinating - specimen of its kind. The book contained (in 1956) 49 items, of which 23 were songs obtained from oral tradition in Kintyre; the remained consisted of 12 songs copied from print (e.g. old numbers of the Campbeltown Courier); 9 poems and song-texts obtained from Campbeltown residents and people living in the area; 4 songs composed by Willie himself, and one sentimental nostalgic 'homeland song' (Oor Ain Glen), with the composer and the writer of the lyric both duly credited … The songs from local tradition in Willie Mitchell's books are all painstakingly documented; the source-singer is given in every case, and detailed notes relating to the song are usually appended.Another Scottish singer that Hamish Henderson met and recorded was Willie Mathieson who, over the years, had filled three ledgers with the texts of several hundred songs that he had heard sung by fellow farm labourers.10

In some ways we may say that the manuscript books created by Willie Mitchell and Willie Mathieson were similar to the one held by the Copper Family of Rottingdean in Sussex.![]() 12

12

'In 1922 James (Copper) was persuaded to write down the words of some of his songs by the daughter of the farmer for whom he had worked for over forty years. These were the old songs that he had loved all his life, songs that he remembered hearing as a boy in the 1840s and '50s. At the foot of one “The Shepherd of the Downs”, he wrote, “My Grandfather used to sing this song.” His grandfather on the paternal side was George Copper who was born in Rottingdean in 1784.The Copper Family continue to refer to their song-book, even when singing on stage, although I suspect that they all know the texts off by heart. And Bob Copper was certainly not averse to learning new songs during his life.

At the end of the day it doesn't really matter whether or not Bob Blake was a 'traditional singer'. Bob, I'm sure, was true to himself, and if a young, inexperienced song collector (i.e. me) was willing to impute a label onto Bob that, with hindsight, was probably inaccurate, then the egg is surely on my face! What really matters is the fact that Bob was a fine singer and luckily we did manage to record him singing some of the songs that he knew. Also, many people today want a world of certainties, a world where our every thought and desire can be seen in terms of black and white. But, of course, life is not like that and, kicking against this, we so often find ourselves suffering from the unsatisfactory nature of things. Bob Blake gave pleasure to many people by singing his songs. Singers like the Coppers, Bob Lewis and George Belton became his friends and accepted him as their equal. I'm glad that I met him and heard him sing, and, at the end of the day, that's what really matters to me.

Mike Yates - 8.8.06

Article MT184

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |