Note: place cursor on red asterisks for footnotes.

Place cursor on graphics for citation and further information.

Article MT288

Blues Jumped a Rabbit

Blues jumped a rabbit and he ran a solid mile.

Blues jumped a rabbit, and he ran a solid mile.

The rabbit sat down and cried just like a little child.

Rabbit-Foot Blues - Blind Lemon Jefferson (1926)

The blues grew out of suffering. They grew out of poverty and out of hopelessness. They grew from the mouths of people whose ancestors had been forcibly removed from their homelands in Africa and who were forced to work as slaves. The blues became the music of the dispossessed.

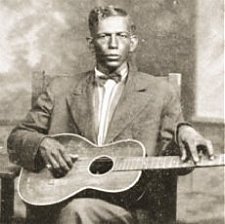

I don't know when I first heard the blues, but in 1959, when I was 16, I bought a copy of Sam Charter's book The Country Blues, possibly because I had already listened to singers such as Big Bill Broonzy on the radio. It must have been around that time that I also came across the Origin Jazz Library set of LPs. The label had been founded by Bill Givens and Pete Whelan and there were a dozen or so albums, each comprising tracks taken from early 78's. They featured singers such as Charlie Patton, Son House, Crying Sam Collins, Skip James, and many other Mississippi greats.  At that time these were just names, but during the '60s a handful of enthusiasts started to scour the American South, rooting out the singers who were still left and discovering the untold story of the blues. And the story was quite simple. The blues, we were told, had begun on the Dockery Plantation in Sunflower County, Mississippi, and Charlie Patton was in there right at the beginning.

At that time these were just names, but during the '60s a handful of enthusiasts started to scour the American South, rooting out the singers who were still left and discovering the untold story of the blues. And the story was quite simple. The blues, we were told, had begun on the Dockery Plantation in Sunflower County, Mississippi, and Charlie Patton was in there right at the beginning. 1

1

When African slaves were taken to America vestiges of their beliefs survived in the minds of the slaves. Many West African villages have shrines devoted to Legba, the person who watches over crossroads, those tricky places where one's life could so easily change. When early Christian missionaries first met Legba they soon decided that he was the equivalent to the Christian Devil. This belief was taken to the Americas by West African slaves and it was said that the bluesman Robert Johnson had met the Devil at the crossroads, where he exchanged his soul for his newly found musical skills.

Went down to the crossroad, fell down on my knees ...

Robert Johnson  2

2

This was recorded on Friday, November 27, 1936. In another song, Hellhound On My Trail, recorded a year later, Johnson mentioned other survivals from Africa:

I've got to keep movin', blues fallin' down like hail

And the days keep on worrying me, there's a hellhound on my trail

And:

You sprinkled hot foot powder, around my door

It keep me with ramblin' mind, every old place I go. 3

3

Voodoo magic can also be found in the lyrics of other Mississippi blues singers, including "Muddy Waters" (McKinley Morganfield) who sang of "mojo hands" "John the Conqueror roots" and "black cat bones" in his songs. 4

4

African slaves, it seemed, had taken their own musical scales to the Americas. These were different from Western scales, and when the two scales met there were sound clashes, which produced so-called 'blue' notes. Many of the slaves also had their own way of coping with their situation. They did this by singing 'hollers', personal songs that spoke of the injustices of life in the American South. 5 This, according to some experts was how the blues began:

5 This, according to some experts was how the blues began:

Mmm - hmm - mmm - ho, ho, Lord

Well, I wonder will I ever get back home?

Hey, hey, oo-hoo, O, Lawd,

Well, it must have been the devil that fooled me here,

For I'm all down and out. 6

6

According to Stephen Calt and Gayle Wardlaw:

The first musician Charlie Patton probably heard was … Lem Nichols. He was forty or fifty at the turn of the century and was noted for "rag" ditties like Spoonful (which Patton would convert into a personal showpiece) and Pearlee, played with a pocket knife. 7

7

This suggests that some of this music, possibly including the blues, had been around for some time before Patton began playing. Calt and Wardlaw again:

The exaltation of Patton as a pioneer blues singer involves a curious deafness to the history his own music proclaims. From a musical standpoint Patton is more sophisticated than the blues form he employed. He is simply too skilled and too given to embellishments to pass muster as a pioneer blues player. Had blues been an entirely new musical word when he took up the form he would have had no reason to impose his individuality on it. His music assumes that his listeners are jaded by blues, and will this applaud the novelties he brings to the idiom. 8

8

But did the blues, as a distinct musical form, actually begin in Mississippi? Alan Lomax seemed to think so when he titled his book about Mississippi and its music The Land Where the Blues Began. 9 Lomax spent a great deal of time travelling throughout the American South and was one of the most perceptive people to have visited the area.

9 Lomax spent a great deal of time travelling throughout the American South and was one of the most perceptive people to have visited the area. 10

10  He was responsible for recording field hollers, such as the one above that had been sung to him by the convict simply known as "Tangle Eye", as well as for stunning blues from any number of performers. He discovered and promoted the man who was to become "Muddy Waters" and recorded such gems as the following from Son House.

He was responsible for recording field hollers, such as the one above that had been sung to him by the convict simply known as "Tangle Eye", as well as for stunning blues from any number of performers. He discovered and promoted the man who was to become "Muddy Waters" and recorded such gems as the following from Son House. 11

11

Well, I got up this mornin', jinx all around, jinx all around, 'round my bed

And I say I got up this mornin', with the jinx all around my bed

Know I thought about you, an' honey, it liked to kill me dead

Oh, look-a here now baby, what you want me, what you want me, me to do?

Look-a here, honey, what you want poor me to do?

You know that I done all I could, just tryin' to get along with you

You know, the blues ain't nothin' but a low-down shakin', low-down shakin', achin' chill

I say the blues is a low-down, old achin' chill

Well, if you ain't had 'em honey, I hope you never will. 12

12

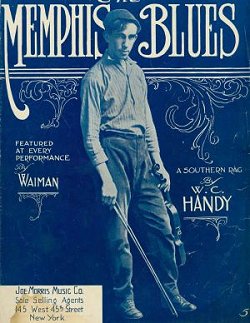

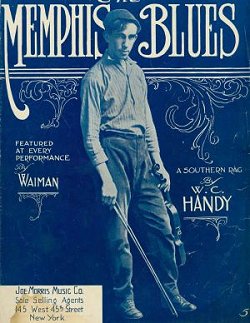

Sometime about 1902 a black American musician and composer, W C Handy (1873 - 1958), took some time out to travel around Mississippi. The following year, in 1903, Handy was waiting for a train in Tutwiler, Mississippi, when he heard:

A lean loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept ... As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars ... The singer repeated the line three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard.

We don't know what the singer was singing, but it has been suggested that it could have been something along the lines of:

I'm a poor boy, a long, long way from home

A poor boy, a long, long way from home

Just a poor boy, a long, long way from home. 13

13

If so, then Handy had heard a 12-bar blues, a format that was to sweep the musical South of America. He also heard "blind singers and footloose bards" in and around Clarksdale, Mississippi, where he was living. They were, he said, "Surrounded by crowds of country folks" and they would "pour their hearts out in song". In 1909 Handy moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he organized a band which played in some of the Beale Street clubs. At that time Edward Crump was the mayor of Memphis and Handy took one of Crump's re-election campaign tunes and turned it into a piece which he called The Memphis Blues, though, in truth, it is a blues in name only. It begins:

Folks I've just been down, down to Memphis town,

That's where the people smile, smile on you all the while.

Hospitality, they were good to me

I couldn't spend a dime, and had the grandest time.

I went out a dancing with a Tennessee dear,

They had a fellow there named Handy with a band you should hear

And while the folks gently swayed, all the band folks played Real harmony.

I never will forget the tune that Handy called the Memphis Blues.

Oh yes, them Blues.

Interestingly, W C Handy also claimed to have written the original campaign song, although others have speculated that it was more likely written by another member of his band. In September, 1927 Memphis singers Frank Stokes & Dan Sane recorded a version of the campaign song for Paramount Records. 14 Their version begins:

14 Their version begins:

Now, Mr Crump don't like it, ain't going to have it here

Now, Mr Crump don't like it, ain't going to have it here

Now, Mr Crump don't like it, ain't going to have it here

No Barrelhouse women, goin' drinkin' no beer

Mr Crump don't like it. He ain't goin' to have it here.

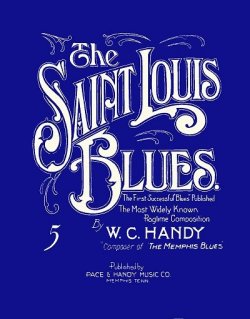

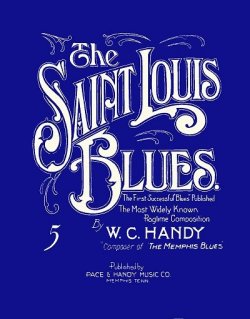

W C Handy continued to compose blues pieces, such as Beale Street Blues, Yellow Dog Blues (originally titled Yellow Dog Rag) and his most famous piece St Louis Blues, which, according to Handy, had been composed after hearing a woman on a St Louis street singing the line 'Ma man's got a heart like a rock cast in de sea'.

Handy was clearly aware of blues singers at the time when his was composing his blues.

The primitive southern Negro, as he sang, was sure to bear down on the third and seventh tone of the scale, slurring between major and minor. Whether in the cotton field of the Delta or on the Levee up St. Louis way, it was always the same. Till then, however, I had never heard this slur used by a more sophisticated Negro, or by any white man. I tried to convey this effect … by introducing flat thirds and sevenths (now called blue notes) into my song, although its prevailing key was major … , and I carried this device into my melody as well … This was a distinct departure, but as itturned out, it touched the spot. 15

15

Here, Handy is describing the 'blue' notes that I mentioned above. He is also quite clearly saying that these notes were being sung by southern Negroes before he began to compose, and popularize, blues music.

W C Handy liked to call himself "the Father of the Blues", but perhaps this was not strictly accurate, because the blues had been born some time before Handy encountered the term. So how do we find out just what it was that the people were singing before Handy began to compose? Well, one way is to examine the recordings that exist of singers who probably picked up some of their repertoire before 1900, and one such singer was Henry Thomas, better known as "Ragtime Tex".

Henry Thomas is believed to have been born in a place called Big Sandy in Texas in 1874. He was a singer who accompanied himself on the guitar and the "quills" - a set of pan-pipes that were carried just under the mouth. During the period 1927 - 29 he recorded a total of twenty-three sides.

Henry Thomas is believed to have been born in a place called Big Sandy in Texas in 1874. He was a singer who accompanied himself on the guitar and the "quills" - a set of pan-pipes that were carried just under the mouth. During the period 1927 - 29 he recorded a total of twenty-three sides. 16 Three songs, Arkansas, Honey, Won't You Allow Me One More Chance? and Woodhouse Blues, can probably be traced back to the Minstrel or Vaudeville traditions, while a further eight songs seem to come from an early tradition where verses were shared between both black and white singers. These are John Henry, The Fox and the Hounds, The Little Red Caboose, Run, Mollie Run, Fishing Blues, Old Country Stomp, Charmin' Betsy and Railroadin' Some.

16 Three songs, Arkansas, Honey, Won't You Allow Me One More Chance? and Woodhouse Blues, can probably be traced back to the Minstrel or Vaudeville traditions, while a further eight songs seem to come from an early tradition where verses were shared between both black and white singers. These are John Henry, The Fox and the Hounds, The Little Red Caboose, Run, Mollie Run, Fishing Blues, Old Country Stomp, Charmin' Betsy and Railroadin' Some.

Take, for example, the song Run, Mollie Run which contains verses from a number of songs, including Poor Liza Jane (Roud 825).

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

Liza was a gambler, learned me how to steal

Learned me how to deal those cards, to hold that jack a trey

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

Music in the kitchen, music in the hall

If you can't come Saturday night, you need not come at all

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

Whoa Liza, poor girl

Whoa Liza Jane

Whoa Liza, poor girl

Died on the train

Miss Liza was a gambler, she learned me how to steal

She learned me how to deal those cards, to hold that jack a trey

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

I went down to Huntsville, I did not go to stay

Just got there in the good old time to wear them ball and chain

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

Cherry, cherry, cherry like a rose

How I love that pretty yellow gal

God almighty knows

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

Poor Liza

Poor Liza Jane

Poor Liza, poor girl

Died on the train

I went down to Huntsville, did not go to stay

Just got there to do old time, to wear them ball and chain

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

Miss Liza was a gambler, she learned me how to steal

She learned me how to deal those cards, a-hold that jack a trey

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

She went down to the bottom (field), did not go to stay

She just got there in the good old time to wear that rollin' ball

Run Mollie run (x3)

Let us have some fun

(According to folklorist Mack McCormick, a dealer who holds out a jack and three seriously reduces his opponent's chances of laying down a sequence in Coon Can or similar card games.)

Henry Thomas also recorded a number of what we might call "Rag Ditties", songs which seem to be the forerunners of blues. These are Red River Blues, Bob McKinney, Don't Ease Me In, Lovin' Babe and Don't Leave Me Here. Lovin' Babe includes the following lines and verses:

Lovin' babe i'm all out and down (x3)

I'm laying close to the ground

Look where the evening sun has gone (x3)

Gone, God knows where

The longest day that ever I seen (x3)

The day Roberta died

Just make me one pallet on your floor

I'll make it so your husband never knows

That eastbound train come and gone (x3)

Gone to come no more.

There are also four songs that could properly be called blues, Cottonfield Blues, Bull Doze Blues, Texas Easy Street Blues and Texas Worried Blues. Looking at Bull Doze Blues we can see that most of the stanzas comprise a single line that is repeated three times, as in the song Poor Boy, a Long, Long Way from Home mentioned above.

I'm going away, babe, and it won't be long

I'm going away and it won't be long

I'm going away and it won't be long

Just as sure as that train leaves out of that Mobile yard

Just as sure as that train leaves out of that Mobile yard

Just as sure as that train leaves out of that Mobile yard

Come shake your hand, tell your papa goodbye

Come shake your hand, tell your papa goodbye

Come shake your hand, tell your papa goodbye

I'm going back to Tennessee

I'm going back to Memphis, Tennessee

I'm going back to Memphis, Tennessee

I'm going where I never get bull-doosed

I'm going where I never get the bull-doosed

I'm going where I never get bull-doosed

If you don't believe I'm sinking

Look what a hole I'm in

If you don't believe I'm sinking

Look what a hole I'm in

If you don't believe I'm sinking

Look what a fool I've been

Oh, my babe, take me back

How in the world …

Lord, take me back.

(This song should be titled Bull Dose Blues, the term being a "Southern colloquialism meaning to bullwhip a black person, or to intimidate through threats of violence". 17

17

Readers who have got this far may have noticed a slight reticence on my part to go along with the "blues began at the Dockery Plantation, on the lips of Charlie Patton" theory. Here is part of a recorded conversation between two American folklorists, Dick Spottswood and Kip Lornell:

KL: So you think the blues started in the Piedmont and not the Delta, huh?

DS: (laughs)

KL: Why's that?

DS: 'cause of that particular phraseology. I'm looking at pieces like Lonesome Road Blues and Careless Love and some of those as being sort of early transitional lyric songs that have complaining elements to them.

KL: "... going down that road feeling bad"?

DS: Well, that's Lonesome Road Blues.

KL :Okay

DS: Lonesome Road Blues I guess is the revisionist title. And I think in the 19th century a lot of those songs were in three quarter time a la Down In The Valley or Birmingham Jail and that they began being in four quarter time, and once you drop the third line of the stanza, instead of singing "Going down the road feeling bad" three times, you only sing it twice. Or Takes a worried man to sing a worried song which you always have to sing that line three times too, right? As soon as you drop that third line you've got something approaching the classic blues stanza.

KL: I also think of those songs as having roots in white culture too.

DS: Sure.

KL: I think there was a very strong shared repertoire in the nineteenth century between blacks and whites, especially in the rural South, and a lot of songs we think of as blues songs now, and certainly that's true of black fiddle and banjo playing, they have common ancestry in both black and white rural traditions. 18

18

DS: Yeah, it almost seems as though those two worlds sort of split apart and became the musics that we know them around the twentieth century. Ma Rainey telling John Work that she encountered the blues in southwest Missouri in 1902. She maybe had heard something like that before but clearly she encountered something at that point that she experienced as something entirely new musically. 19

19

KL: And I think a lot of that has to do with the Jim Crow laws of the 1890's kind of reinforcing what was once freedom or a semblance of freedom for blacks, all of a sudden the Jim Crow laws come in in the mid 1890s and zap, it's like being back towards slavery again. I think that really signals a seachange in American culture.

DS: Well the desired effect was to push the races apart physically and it certainly had that effect. Maybe that gave black culture the chance to put some flesh on those skeletal blues bones.

KL :It certainly happened right around the turn of the century and that seems to be the main legal and social impetus for that happening at that time.

DS: But even after that blues was always sort of crossing the street of the racial divide. Hart A Wand's Dallas Blues and all the Handy's Memphis Blues and Beale Street Blues of the teens kept pushing those songs back towards white culture again still even with the earliest recordings that we know, which is actually all that we can still hear. Mamie Smith is still singing something that has a distinctively racial component and it's not really until you get to Jimmie Rodgers in 1927, and this time exclusively via phonograph records, that you have somebody deliberately dragging blues back across the racial street again. 20

20

KL: Yeah, there are a few earlier examples but Jimmie Rodgers was the one who put blues in the American mainstream.

DS: I think you'd have to say Handy and Rodgers both.

KL: And Handy especially through the publishing ... the sheet music starting about 1912, 1913, really helped, for people who could afford sheet music, who were interested in sheet music and I'm willing to guess that was many, many more white people than black people.

In truth, it seems almost impossible to tie the blues down to any one place or person. In 2010 Peter C Muir showed that while the term "blues" became especially popular in the period 1912 - 1920, the term had existed long before these dates. 21 And one writer, Max Haynes from Lancaster University, managed to show that many blues singers actually used phrases, lines and even whole songs which had originally come from, of all places, the 19th century British Music Hall.

21 And one writer, Max Haynes from Lancaster University, managed to show that many blues singers actually used phrases, lines and even whole songs which had originally come from, of all places, the 19th century British Music Hall. 22

22

Peter Muir's cut-off date of 1920 is an interesting choice, because shortly afterwards the first recordings of blues singers began to be heard across America. This also means that recordings, which had been made from singers all over the American South and East Coast, are still available today for us to listen to. And what recordings these are!

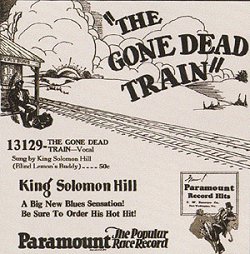

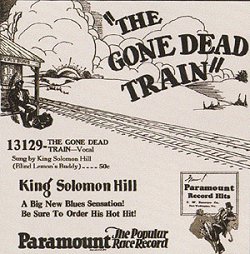

One of my favourite singers was a man who recorded under the name of 'King Solomon Hill', and who sometimes billed himself as 'Blind Lemon's Buddy' - presumably after Blind Lemon Jefferson.

One of my favourite singers was a man who recorded under the name of 'King Solomon Hill', and who sometimes billed himself as 'Blind Lemon's Buddy' - presumably after Blind Lemon Jefferson.

'Hill' recorded eight songs for Paramount Records in 1932, a time when Paramount was about to go under, and it is doubtful if the company pressed many of Hill's records. Copies are certainly rare today. The titles recorded are as follows: Down on My Bended Knee (Take 1), Down on My Bended Knee (Take 2), The Gone Dead Train, My Buddy Blind Papa Lemon, Tell Me Baby, Times Has Done Got Hard, Whoopee Blues (Take 1) and Whoopee Blues (Take 2).

At first it was thought that the singer Big Joe Williams had used the 'King Solomon Hill' name for some of his recordings, though, aurally, the singers were dissimilar. There then followed a disagreement between an academic, Professor David Evans, and an amateur (in the best sense of the word) blues aficionado called Gayle Dean Wardlaw. Evans claimed to have discovered the true identity of 'King Solomon Hill', without, it seems, ever having presented his findings in public. Wardlaw, on the other hand, identified 'Hill' as one Joe Holmes (1897-1949) who came from Sibley, near Minden, in Louisiana, and he published the facts as early as 1967. Evans replied by calling Wardlaw's findings 'a fiasco'. Wardlaw continued to beaver away on the 'King Solomon Hill' story, before publishing a second set of findings in 1987. This time Wardlaw showed that Joe Holmes had lived at a place in Sibley called King Solomon Hill, a hill where the King Solomon Hill Baptist Church once flourished. All the people in Sibley who remembered Joe Holmes, and who were certain that the recordings were indeed by Holmes, had never heard him use the name 'King Solomon Hill', which was actually Holme's mail address. So had the people at Paramount become confused with Joe's deep-south accent, or had they just thought that the name 'King Solomon Hill' might sell more records? 23 Surprisingly, David Evans continues to deny that Joe Holmes and 'King Solomon Hill' were one and the same. In 2008 Evans wrote a paper, 'Nicknames of Blues Singers' where he said, 'A couple of these examples, King Solomon Hill and Prince Moore, may not be nicknames at all but simply given names'.

23 Surprisingly, David Evans continues to deny that Joe Holmes and 'King Solomon Hill' were one and the same. In 2008 Evans wrote a paper, 'Nicknames of Blues Singers' where he said, 'A couple of these examples, King Solomon Hill and Prince Moore, may not be nicknames at all but simply given names'. 24

24

Perhaps my favourite King Solomon Hill recording is that of The Gone Dead Train, with its almost surreal title.

And I'm goin' way down (or going Minden)

And I'm goin' way down (or going Minden)

Lord, I'm gonna try to leave here today

Tell 'em I believe I'll find my way

And that train is just that way

Gotta go on that train

I said I'd even broke my jaw

Boys, if you out and runnin' around in this world

This train will wreck your mind

(Spoken: Your life, too)

Lord, I once was a hobo

I crossed a many a point

But I decided I'd go down to Fryeberg light

And take it as it comes

(Spoken: I reckon' you know the fireman and the engineer would, too)

There are so many people have gone down today

And this fast train north and southern traveling light and clear

Oooo-ooh, I wanna ride your train

I said, "Look here, engineer, can I ride your train?"

He said, "Look here, you oughta know this train ain't mine

And you're asking me in vain"

Said, "You go to the Western Union, you might get a chance"

(Spoken: I didn't know the Western Union run no train)

Said, "You go to the Western Union, you might get a chance"

You might get wire to some of your people and your fare will be sent right here

(Spoken: Hadn't thought that's the way it is)

I wanna go home, and that train is done gone dead

I wanna go, that train is done gone dead

I done lost my wife and my three little children

And my mother's sick in bed

Oooo-ooh please, help me win my fare

'Cause I'm a travelin' man, boys I can't stay here. 25

25

The Gone Dead Train depicts the life of the hobo. It is the world of the rambler and of the dispossessed. And this is surely central to the blues, which is, after all, the music of a people stolen in the first place from Africa and, subsequently, treated as no more than chattels, objects to be bought and sold at will. It is the music of people living in a world of insecurity, one where men and women, who might have managed to form some kind of stable relationships, could, at any moment be split apart and separated. And that is probably why so many blues deal with insecure relationships between couples. The blues were a legacy of all the injustices that had befallen hundreds of thousands of people.

And yet, despite all that had gone before, illiterate and semi-illiterate blues singers were able to express themselves with a poetry that almost defies definition. Take this piece written by one of the most prolific singers, Blind Willie McTell of Georgia, a man who was himself no stranger to the rambling life:

Wake up mama don't you sleep so hard

Wake up mama don't you sleep so hard

For its these old blues walkin' all over your yard

I've got those blues, I'm not satisfied

I've got those blues, I'm not satisfied

That's the reason I'm sure long way to cry

Blues arrived at midnight, won't turn me loose 'till day

Blues arrived at midnight, won't turn me loose 'till day

I didn't have no mama to drive these blues away

The big star fallin', mama t'ain't long (be)fo'(re) day

The big star fallin', mama t'ain't long (be)fo'(re) day

Rain or sunshine drive these blues away

Oh come here quick, come on mama, I got you ...

Mmm ... 26

26

In 1940 John Lomax and his wife, Ruby, encountered McTell in Atlanta. They persuaded him to call round to their hotel room, where they recorded some of his songs for the Library of Congress. They also recorded some short interviews; including one which Lomax titled "Monologue on Accidents". Lomax was seeking "any songs about coloured people having hard time here in the South", but Willie denied knowing any such pieces. "Are there any complaining songs, complaining about the hard times? Sometimes mistreatment by the white, have you any songs that talk about that?" to which Willie replies, "Not at the present time, because the whites is mighty good to the southern people, as far as I know." This seems to throw Lomax, who, nevertheless presses on. "You don't know any complaining songs at all? Ain't It Hard to be a Nigger, Nigger - do you know that one?" After a short pause, Willie replies, "That is not in our time … there's a spiritual It's a Mean World to Live In, but that don't have reference about hard times." So Lomax asks, "Why is it a mean world?" to which Willie answers, "It has reference to everybody." Lomax, who seems to be slowly cottoning on, continues, "Is it as mean for the whites as it is for the blacks? Is that it? And Willie replies, "That's 'bout it." At this point Lomax notices that Willie is moving his body about. "You keep moving around, like you are uncomfortable?" Doubtless Willie was, indeed, uncomfortable, having been asked by a white man if he knew any songs about coloured folk being mistreated by the whites, but he gets round this by quickly answering that he had been involved in a motor accident the previous night, which had left him "a little shook up"!

"Monologue on Accidents" tells us as much about the white John Lomax as it does about the black Willie McTell. Lomax, a man previously unknown to McTell, clearly believed that McTell would sing "protest" songs to a complete stranger, and this at a time when black people, who "stepped out of line", were being lynched in the South. Lomax's naivety is truly remarkable. And yet, a few years before John Lomax met Blind Willie McTell, another white man, Lawrence Gellert, did manage to record a whole batch of protest songs from black singers in the South.

Gellert, unlike John Lomax who was a southerner from Texas, was born in Hungary in 1898, but moved to New York when he was seven. And, again unlike Lomax, he was, politically, well to the left, often writing for the communist magazine Masses (later New Masses). In the early 1920s he settled in Tryon NC, because of poor health. During the period 1933 - 37 Gellert made field recordings of black singers and musicians in both North and South Carolina, Mississippi and Georgia. In total he made 221 aluminium, zinc and lacquer discs - containing some 600 songs, half of which might be called "protest songs" - which are now housed in Indiana University. Lawrence Gellert produced the book Negro Songs of Protest in 1936, much to the surprise of many people who were unaware that such songs existed. One notable critic was John Lomax! Me and My Captain, Negro Songs of Protest Volume 2 appeared in 1939. Although Gellert's death is given as 1979, it seems that he "just disappeared" sometime around this date.

In 1973 Rounder Records issued the first of two LPs of material from the Gellert collection, Negro Songs of Protest (Rounder LP 4004), while volume 2, Cap'n You're So Mean - Negro Songs of Protest, Volume 2 (Rounder 4013) appeared in 1982. Sadly, they have not been reissued on CD format. However, a further sixteen of Gellert's recordings can be heard on the Document CD Field Recordings - Volume 9 (DOCD-5599). 27 All the performers heard on these three albums are "anonymous". Earlier this year, Bruce Conforth of the University of Michigan produced a biography of Lawrence Gellert, African American Folksong and American Cultural Politics: The Lawrence Gellert Story (Scarecrow Press - an imprint of Rowman and Littlefield).

27 All the performers heard on these three albums are "anonymous". Earlier this year, Bruce Conforth of the University of Michigan produced a biography of Lawrence Gellert, African American Folksong and American Cultural Politics: The Lawrence Gellert Story (Scarecrow Press - an imprint of Rowman and Littlefield).

I once got into a heated debate with a Scottish academic when I suggested that Robert Burns was steeped in a folksong tradition and that Burns used much of this tradition in his poems. The academic, who seemed to think that Burns's every word had been composed by Burns himself, just could not accept what I was saying. And the same, I think, may be said of the blues. The early blues developed in a tradition, with lines and verses passing from mouth to mouth. But, as with Burns, there were extremely talented individuals within this tradition, singers such as Charlie Patton, Son House, Henry Thomas, King Solomon Hill or Willie McTell, who had the ability to transcend other singers with their individual genius.

Today we may sit back and listen to these voices, voices that are removed in time, but not in substance. Willie McTell's Mama T'ain't Long Fo' Day is as fresh and relevant today as it was on 18th October, 1927, when Willie sat down in front of a recording machine in Atlanta, GA. Close your eyes and you are with him in the room, listening to a man who had the same feelings and desires as us; a man who wanted justice, both for himself and for his people, yet who had suffered from the indignity of a system that had denied him those basic rights. How, I keep wondering, could a system like that throw up such superb musicians, poets and dreamers? How could so many people survive - because that is what they did - in such harsh circumstances? The answer, I guess, is there to be heard, in the thousands of blues that were sung for so many, long years.

Mike Yates - 11.11.13

Notes:

1. See Gayle Dean Wardlaw, Chasin' That Devil Music Miller Freeman Books, San Francisco, 1998, and Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlaw, King of the Delta Blues. The Life and Music of Charlie Patton Rock Chapel Press, Newton, New Jersey, 1988, for the Mississippi roots of the blues. It should be pointed out that they do not go along with the idea of Charlie Patton being the 'founder' of the blues.

2. Robert Johnson Crossroad Blues Recorded 1936 and reissued on several CDs.

3. Robert Johnson Hellhound On My Trail Recorded 1937 and reissued on several CDs.

4. These Afro-American phrases, which relate to Voodoo, can be found in songs such as Muddy Waters' I'm a Hoochie Coochie Man which has been reissued on several CDs. Other examples include, 'I believe my good gal have found my black cat bone/I can leave Sunday mornin' Monday mornin' I'm tippin' 'round home' (Blind Lemon Jefferson Broke and Hungry,1926). A black cat bone is believed to make its owner invisible and increase the owner's sexual prowess. 'I'm gonna sprinkle a little goofer dust all around your nappy head/You wake up some of these mornings, find your own self dead' (Charlie Spand Big Fat Mama Blues,1929). Goofer dust is collected from a graveyard. It can cause sickness and death in an enemy, and probably comes from an African KiKongo word, kufwa, which means 'to die'. 'My rider's got a mojo, she's tryin' to keep it hid/But papa's got somethin' for to find that mojo with' (Blind Lemon Jefferson Low Down Mojo Blues, 1928). Mojo, or jomo , is a collection of magical substances held about the person in a small pouch. It enhances luck and is similar to a Gullah term for witchcraft, moco, which, in turn, may come from an African Fula word, moco'o, which means a witchdoctor. Finally, 'I'm going to New Orleans, to get this toby fixed of mine/I am havin' trouble, trouble, I can't keep from cryin'' (Hattie Hart Spider's Nest Blues, 1930). A toby is a charm (often a rabbit's foot). It is related to the Caribbean word obeah, an idiom for conjuring. According to the OED an obeah can make the bearer invisible. It would seem likely that toby/obeah comes originally from an African word.

Other examples of American retentions of African beliefs can be found in several of Robert Thompson's books, including The Four Moments of the Sun. Kongo Art in Two Worlds (1981), Flash of the Spirit. African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (1984), Face of the Gods. Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas (1993) and Aesthetic of the Cool. Afro-Atlantic Art and Music (2011).

5. Recorded examples of 'hollers' can be heard on a number of recordings, including: Prison Songs. Historical Recordings from the Parchman Farm, 1947 - 48. Volume One: Murderer's Home. Prison Songs. Historical Recordings from the Parchman Farm, 1947 - 48. Volume Two: Don'tcha Hear Poor Mother calling? Rounder CD 1715. Sounds of the South: A Musical Journey from the Georgia Sea islands to the Mississippi Delta Atlantic 7 82496 - 2 (4 CD set).

6. Tangle Eye Blues sung by Walter 'Tangle Eye' Jackson. Rounder CD. Prison Songs. Historical Recordings from the Parchman Farm, 1947 - 48. Volume One: Murderer's Home. Rounder CD 1714. Also available on Rounder CD 1866. Alan Lomax - Blues Songbook. Disc 1.

7. Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlaw, King of the Delta Blues. The Life and Music of Charlie Patton Rock Chapel Press, Newton, New Jersey, 1988. For the Mississippi roots of the blues, see p.46.

8. Ibid p.47.

9. Alan Lomax, The Land Where the Blues Began 1993. The New Press (New Edition), 2002.

10. For a biography of Alan Lomax, see John Szwed's The Man Who Recorded the World Arrow Books, London. 2010.

11. For the Lomax/ Muddy Waters recordings, see The Complete Plantation Recordings. Muddy Waters, the Historic 1941 - 42 Library of Congress Field Recordings Chess/MCA MCD09344/CHD-9344.

12. John Szwed's The Man Who Recorded the World Arrow Books, London. 2010. p.181.

13. For some recorded versions of Poor Boy a Long Way from Home see John Dudley (Rounder CD 1703. Southern Journey. Volume 3 - Delta Country Blues, Spirituals, Work Songs & Dance Music). Gus Cannon (Document Records DCOD-5032 Gus Cannon, Volume 1, 1927 - 1928). Bo Weavil Jackson (Document Records DOCD-5036 Backwoods Blues (1926 - 1935). Barbecue Bob (Robert Hicks) (Document Records DOCD-5046. Barbecue Bob - Complete Recorded Works. Volume 1. 25 March, 1927 - 13 April, 1928). Buell Kazee ( JSP Records JSP77100 - 4 CD set - Mountain Frolic).

14. Reissued on Document CD DOCD-5012 The Beale Street Sheiks (Stokes & Sane) 1927-1929.

15. Quotes from W C Handy are in W C Handy, Arna Wendell Bontemps, Father of the Blues: An Autobiography, Da Capo Press, 1991.

16. All of Henry Thomas's sides are available on a Yazoo CD Henry Thomas. Complete Recorded Works, 1927 - 1929 (Yazoo 1080/1). I am indebted to Stephen Calt, who wrote the CD's booklet notes, for what is said about Henry Thomas above.

17. Stephen Calt, Barrelhouse Words. A Blues Dialect Dictionary University of Illinois Press, Urban & Chicago, 2009, p.40.

18. For recordings of black musicians playing tunes from a common black/white repertoire, see Black Fiddlers (Document DOCD-5631), Black Banjo Songsters of North Carolina and Virginia (Smithsonian-Folkways SFW 40079, Altamon - Black Stringband Music (Rounder 0238) and Deep River of Song - Black Appalachia. String Bands, Songsters and Hoedowns (Rounder 1823).

19. As previously mentioned, 1902 was the year when W C Handy started travelling around Mississippi.

20. Jimmy Rodger's recordings are available on several reissue CD sets.

21. Peter C. Muir Long Lost Blues. Popular Blues in America, 1850 - 1920 University of Illinois Press, Urbana & Chicago. 2010.

22. Max Haymes's The English Music Hall Connection can be found, in several parts, on: www.earlyblues.com

23. For both of Gayle Dean Wardlaw's articles, see his book Chasin' That Devil Music - Searching for the Blues Miller Freeman Books, San Francisco, 1998. pp.2 - 7 & 208 - 218.

24. David Evans (editor) Ramblin' on my Mind . New Perspectives on the Blues University of Illinois Press, Urbana & Chicago. 2008. p.200.

25. Six of King Solomon Hill's recordings, including The Gone Dead Train, can be heard on Document CD Backwood Blues (DOCD-5036). The two remaining tracks, My Buddy Blind Papa Lemon and Times Has Done Got Hard can be heard on 2 CDs Times Ain't Like They Used to Be (Yazoo 2067 & 2068). It should be noted that Hill's recordings can be hard to understand at times and the transcription given above may contain some mistakes.

26. Blind Willie McTell's Mama T'ain't Long Fo' Day, recorded in 1927, has been reissued as part of the 4 CD set Blind Willie McTell - 1927 - 1940, The Classic Years JSP 7711.

27. The songs of Rounder LP 4004 are: Cold Iron Shackles, Two Hoboes, Negro Got No Justice, Mail Day I Gets A Letter, Rocky Bottom, Come Get Your Money, Joe Brown's Coal Mine, You Ask For Breakfast, On A Monday, There Ain't No Heaven, In Atlanta, Georgia, Cap'n Got A Lueger, When Sun Go Down, Give Me Fifteen Minutes And You Calls It Noon, Lawdy Mamie, Cap'n Got A Pistol, Cap'n What Is On Your Mind?, Mr Tyree.

The songs on Rounder LP 4013 are: Cap'n You're So Mean, Don't Go To Georgia, Listen Here Cap'n, This Ol' Hammer, Joe Brown, Nine Pound Hammer, You Don't Know My Mind, Cap'n You Oughta Be Shamed, Standin' On The Streets Of Birmingham, Trouble, Trouble, 30 Blows From Time, Gonna Leave Atlanta, Chain Gang Blues, Red Cross Store, Annie Lee, Why Didn't Somebody Tell Me, Please Bossman Tell Me, Cap'n Hide Me, Delia, White Folks Ain't Jesus (How Long), I went On Down To Okalonda, Trouble In Mind, Cap'n Cap'n.

The Document recordings (DOCD-5599) are: Boogie Lovin', 30 Days In Jail, Ding Dong Ring, Pick & Shovel Cap'n, 6 Months Ain't No Sentence, Hard Times Hard Times, Trouble Ain't Nothin But A Good Man Feelin Bad, Down In The Chain Gang, Prison Bound Blues, Georgia Chain Gang, Gonna Leave From Georgia, Black Woman, Shootin' Craps & Gamblin, Nobody Knows My Name, I Been Pickin' & Shovellin'.

Article MT288

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 11.11.13

At that time these were just names, but during the '60s a handful of enthusiasts started to scour the American South, rooting out the singers who were still left and discovering the untold story of the blues. And the story was quite simple. The blues, we were told, had begun on the Dockery Plantation in Sunflower County, Mississippi, and Charlie Patton was in there right at the beginning.

At that time these were just names, but during the '60s a handful of enthusiasts started to scour the American South, rooting out the singers who were still left and discovering the untold story of the blues. And the story was quite simple. The blues, we were told, had begun on the Dockery Plantation in Sunflower County, Mississippi, and Charlie Patton was in there right at the beginning. He was responsible for recording field hollers, such as the one above that had been sung to him by the convict simply known as "Tangle Eye", as well as for stunning blues from any number of performers. He discovered and promoted the man who was to become "Muddy Waters" and recorded such gems as the following from Son House.

He was responsible for recording field hollers, such as the one above that had been sung to him by the convict simply known as "Tangle Eye", as well as for stunning blues from any number of performers. He discovered and promoted the man who was to become "Muddy Waters" and recorded such gems as the following from Son House.

Henry Thomas is believed to have been born in a place called Big Sandy in Texas in 1874. He was a singer who accompanied himself on the guitar and the "quills" - a set of pan-pipes that were carried just under the mouth. During the period 1927 - 29 he recorded a total of twenty-three sides.

Henry Thomas is believed to have been born in a place called Big Sandy in Texas in 1874. He was a singer who accompanied himself on the guitar and the "quills" - a set of pan-pipes that were carried just under the mouth. During the period 1927 - 29 he recorded a total of twenty-three sides. One of my favourite singers was a man who recorded under the name of 'King Solomon Hill', and who sometimes billed himself as 'Blind Lemon's Buddy' - presumably after Blind Lemon Jefferson.

One of my favourite singers was a man who recorded under the name of 'King Solomon Hill', and who sometimes billed himself as 'Blind Lemon's Buddy' - presumably after Blind Lemon Jefferson.

And I'm goin' way down (or going Minden)

And I'm goin' way down (or going Minden)