Article MT021

Play Me Something Quick and Devilish

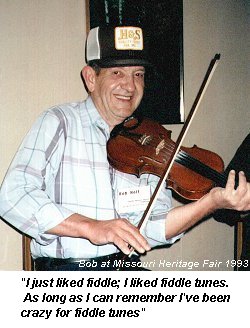

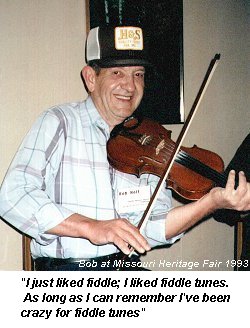

Bob Holt - Old-Time Square Dance Fiddler

"When they think of a dance", Ava guitarist Alvie Dooms once told me, "they think of Holt - in this country, anyhow." "This country" is the southwestern Missouri Ozarks, and 'Holt' is Bob Holt,  whose fiddle playing has become synonymous with dance music in a part of the Ozarks where (despite the proximity of the country music mecca of Branson) traditional square dancing has managed to hold its own as a community recreation. Throughout the winter there is at least one square dance a weekend, either in Douglas County or neighboring Taney County; and the fiddle player is nearly always 'Holt'.

whose fiddle playing has become synonymous with dance music in a part of the Ozarks where (despite the proximity of the country music mecca of Branson) traditional square dancing has managed to hold its own as a community recreation. Throughout the winter there is at least one square dance a weekend, either in Douglas County or neighboring Taney County; and the fiddle player is nearly always 'Holt'.

Bob Holt was born in 1930 near Ava, Missouri, into a family of musicians and dancers which included his paternal grandmother, two uncles, and his father John, who, although unable to play an instrument, was (by Bob's account) a first-rate whistler. "He could whistle a perfect fiddle tune, bow shuffles and all. He had it. And he knew every fiddle tune, just about, he ever heard." In fact, Bob learned a number of tunes from his father's whistling, and even recalls his father correcting him when he went astray. The elder Holt was also an extremely avid dancer - "dance crazy," according to Bob.

When I lived in Ioway, I'd usually come home at night. I'd leave up there after work, and I'd get home about three-thirty or four o'clock in the morning - and get down here, you know, on vacations and weekends. And even in the middle o' the night like that, when I'd come in, he'd say, "Get that old fiddle, boy, and play me a tune!" He liked fiddle music better than anybody I ever seen.

John Holt (whose family had moved from Tennessee to a farm near Ava in 1889, when John was seven) sought to impart his enthusiasm for dance music to his children, and bought Bob (who showed the greatest interest) his first fiddle when he was fifteen. But Bob, who had played harmonica since he was four and later played the mandolin (as well as the baritone horn and trumpet in the school band) "didn't really care much about [the fiddle]" at first, although eventually he "just got to playing it more and more and let the mandolin go." He began playing for local dances - which at that time were still usually held in houses - when he was sixteen or seventeen, shortly after World War II. "And, o' course, there wasn't very many fiddlers around. The old-time fiddlers had mostly got too old. And there just wasn't any young fiddlers around much. And I played practically every Saturday night - you know - in a house dance. That was in, like, early '50s."

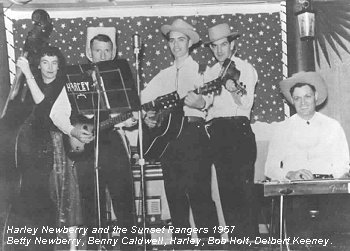

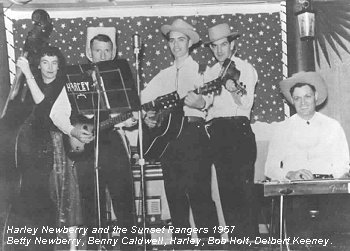

In 1953, due to drought and a farming depression at home,Bob and his young family moved to Buffalo, Iowa, near the Quad Cities, where they remained until 1965.  During this period, Bob worked in a cabinet factory and later attended barber school, playing on weekends for dances or at nightclubs in a country band. Here he began his long-time association with guitarist and singer Harley Newberry (whom Bob calls the best country singer he's ever heard "runnin' around loose") and his wife Betty, who played bass with the band. According to Bob, the only thing that "justified" his presence in the band were the several square dances he would play during the course of each performance. Later, when bluegrass had begun to supersede the older country bands, Bob joined a group which played bluegrass and "a little folk." But while he appreciated the skills of his fellow musicians and enjoyed performing with them, such contexts had their drawbacks for Bob.

During this period, Bob worked in a cabinet factory and later attended barber school, playing on weekends for dances or at nightclubs in a country band. Here he began his long-time association with guitarist and singer Harley Newberry (whom Bob calls the best country singer he's ever heard "runnin' around loose") and his wife Betty, who played bass with the band. According to Bob, the only thing that "justified" his presence in the band were the several square dances he would play during the course of each performance. Later, when bluegrass had begun to supersede the older country bands, Bob joined a group which played bluegrass and "a little folk." But while he appreciated the skills of his fellow musicians and enjoyed performing with them, such contexts had their drawbacks for Bob.

I played Orange Blossom Special as many as ten times in one night. Night after night after night. I played it till I got sick every time I thought of it. I didn't ever like the tune to begin with; but when you play like that, you've got to play it. Even down here at Branson ... anywhere you play, if you're playin' requests, you know that's gonna be your every other request. There's just no way around it. That's why I'd rather milk cows for a livin' and then play for fun. Then I can play what I want to!

After Bob returned to Ava - and eventually to full-time farming - he continued to play music. He even appeared on the Slim Wilson Show (broadcast from Springfield, Missouri) in 1968, along with Bolivar, Missouri, fiddler Buster Fellows, with whom he occasionally performed in area clubs. Locally, he "played with all these different groups," but experienced a growing sense of musical frustration as time went on. "I couldn't get anybody interested in learnin' any tunes or doin' anything different. They just wanted to play these same old things - mostly bluegrassy type stuff. And I just got tired of it, and kinda quit. Because that wasn't really what I wanted to play."

Bob's enthusiasm was rekindled in the mid-'70s, however, by visiting members of the Missouri Friends of the Folk Arts and by his subsequent involvement in the Frontier Folklife Festival in St Louis, at which he performed for four consecutive years.  "That got me started up again," says Bob, "When I found out there was still some real music in the world - and people interested in it." (sound clip - Bull at the Waggon) Since then, he has also performed at such events as the National Folk Festival, the Wheatland Music Festival, and the Chicago Folk Festival. After he began playing in festivals, Bob played more at home too, first with guitarist and friend Alvie Dooms (occasionally assisted by fiddler and bassist H K Silvey), then (after Harley and Betty Newberry's return from Iowa) more and more frequently as a part of a larger dance band consisting of Bob, Alvie, the Newberrys, and rhythm banjo-player/guitarist/fiddler Jim Beeler and his wife Patty, who shares singing duties with Harley. "But always before that I've played the annual big dances, like Hootin' and Hollerin' and Glade Top Trail, and those things. Me and Alvie's played them for years, pretty much."

"That got me started up again," says Bob, "When I found out there was still some real music in the world - and people interested in it." (sound clip - Bull at the Waggon) Since then, he has also performed at such events as the National Folk Festival, the Wheatland Music Festival, and the Chicago Folk Festival. After he began playing in festivals, Bob played more at home too, first with guitarist and friend Alvie Dooms (occasionally assisted by fiddler and bassist H K Silvey), then (after Harley and Betty Newberry's return from Iowa) more and more frequently as a part of a larger dance band consisting of Bob, Alvie, the Newberrys, and rhythm banjo-player/guitarist/fiddler Jim Beeler and his wife Patty, who shares singing duties with Harley. "But always before that I've played the annual big dances, like Hootin' and Hollerin' and Glade Top Trail, and those things. Me and Alvie's played them for years, pretty much."

For the past several years Bob has also been a regular participant in the weekly music parties at McClurg, Missouri, where he indulges in his second favorite musical format, "a good jam session." He has taught fiddle since1987 as a part of the Missouri Arts Council Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program, an activity he has come to enjoy, in spite of initial reservations: "I didn't think I could teach - because I didn't know what I was doin' anyway. In fact, it's prob'ly the first time I gave any conscious - just hard thought - to what I was doin' or how I was doin' it."

Several years ago, Bob met the late Larry McBride, who expressed a desire to record Bob's music for release on his Marimac label. Unfortunately, Larry was never able to complete this project; but the idea, along with the urgent requests of local dancers, prompted Bob in 1993 to record a locally produced tape of square dance music called Rabbit in the Pea Patch. The tape features his regular dance group, the State of the Ozarks String Band, a name he also uses for a concert trio consisting of himself, Alvie Dooms, and banjo-player Karen Kraft. He also appears on Jump Fingers, a tape of Missouri dance music released in 1993 by the Childgrove Country Dancers of St Louis. He still hopes to make a professional recording of some the more unusual tunes in his repertoire, however - one made more for listening than for dancing.

Bob's musical influences are many and varied, and include both his father and his father's brother Noah (or Uncle Node, as he was known to the family), who played five-string banjo.  At a time when clawhammer players were already becoming rare in the Ozarks (the majority played chordal backup), Node Holt played (according to Bob) "just as near note for note as you could possibly play with a banjo. I learned a lotta tunes from his banjo playin', and when I later heard 'em played on the fiddle, I didn't have to change 'em much." Although his mother's brother, Bill Thompson, also played fiddle, Bob learned few tunes from him because he lived too far away for frequent encounters, in Rogersville, Missouri. He did, however, "get the basics" of several tunes from him - as well as "the idea for" cross-key fiddling.

At a time when clawhammer players were already becoming rare in the Ozarks (the majority played chordal backup), Node Holt played (according to Bob) "just as near note for note as you could possibly play with a banjo. I learned a lotta tunes from his banjo playin', and when I later heard 'em played on the fiddle, I didn't have to change 'em much." Although his mother's brother, Bill Thompson, also played fiddle, Bob learned few tunes from him because he lived too far away for frequent encounters, in Rogersville, Missouri. He did, however, "get the basics" of several tunes from him - as well as "the idea for" cross-key fiddling.

Bob also learned tunes from two families of musicians, the Deckards and the Potters, with whom, however, he had little contact,  as they were by then becoming too elderly to attend social events. (sound clip - The Old Stillhouse, learned from his father's whistling and Uncle Node's banjo plying, which they in turn had learned from the Deckards and the Potters.) In fact, he says, most of the other old-time fiddlers in the area at the time were also "real old." He learned "a tune or two" from each, but "never played with anybody enough - or listened to 'em enough - for them to have any particular influence on me." Still, some of his most distinctive tunes - ones he considers indigenous to (or at least typical of) the Ozarks - are those he learned from such sources: tunes like Rabbit in the Pea Patch, Wolves A-Howlin', Hop Up Kittypuss (not to be confused with the Buddy Thomas tune of the same name), Brown's Dream (which the late Art Galbraith called McCraw's Ford), and an unusual version of The Eighth of January which Bob has dubbed The Ninth of January to distinguish it from the more common version. "O' course," he comments, "all those tunes I learned back early - you know, you add to 'em, you change your tunes; and I wouldn't say I played 'em just exactly like I learned 'em back then." "They just evolve ... as you progress, they progress."

as they were by then becoming too elderly to attend social events. (sound clip - The Old Stillhouse, learned from his father's whistling and Uncle Node's banjo plying, which they in turn had learned from the Deckards and the Potters.) In fact, he says, most of the other old-time fiddlers in the area at the time were also "real old." He learned "a tune or two" from each, but "never played with anybody enough - or listened to 'em enough - for them to have any particular influence on me." Still, some of his most distinctive tunes - ones he considers indigenous to (or at least typical of) the Ozarks - are those he learned from such sources: tunes like Rabbit in the Pea Patch, Wolves A-Howlin', Hop Up Kittypuss (not to be confused with the Buddy Thomas tune of the same name), Brown's Dream (which the late Art Galbraith called McCraw's Ford), and an unusual version of The Eighth of January which Bob has dubbed The Ninth of January to distinguish it from the more common version. "O' course," he comments, "all those tunes I learned back early - you know, you add to 'em, you change your tunes; and I wouldn't say I played 'em just exactly like I learned 'em back then." "They just evolve ... as you progress, they progress."

Radio and records were also an important influence on Bob's playing. "My grandma had most every new record that come out. And I played them: they was babysitters when I was little and would go to her house. And those tunes was just ingrained in my consciousness, you know. I knew them a long time before I could play anything." He also recalls when "me and my two brothers rode an old mule across the hill over here to a neighbor's house in 19 - be '35 or '6 - the first time I ever heard the Grand Ole Opry." His favorite performers included the Skillet Lickers, Doc Roberts, Lonnie Robertson, Arthur Smith, and Buster Fellows. And while he says he didn't consciously imitate anyone ("sound was all I had to go on") he admits being particularly influenced by the drive of Buster Fellows (whom he calls "the best square dance fiddler I've ever heard") and the smooth bowing style of Arthur Smith. "Now, our old, old fiddlers that I heard play when I 'as a kid, they 'as much more like the Appalachian style. But you've gotta remember that I come up since Arthur Smith days; and Arthur Smith was kinda the turnin' point, and got into more rollin' fiddlin'."

Thus, while he subscribes somewhat to the geographical theory of American fiddle styles ("chopped" and angular in the Appalachians, but becoming increasingly smooth - with "less of the real jig bow" - with each western remove), he also believes that "... time has done a lot, too. Now, there's no way that radio and records hasn't influenced music in a big way - you know. I know it has. And it couldn't help but done mine, because I've heard radio most o' my life." Yet Bob has a distinctive style which is very much his own - though, like most styles, it eludes easy definition. "You can't take away your own personal touch. It'll be there; there's nothin' you can do about that. That's just your whole style. It's a number of things: it's the way you hear, and the way you bow, and the way you note. Your accents and all that." Bob is also an identifiably Ozarks fiddler, though again definition is problematic, particularly given the variety of individual styles encompassed by that designation. As he once commented aptly, fiddle styles, like regional accents, are much easier to recognize than to define.

While Bob's repertoire includes waltzes, schottisches, blues, and rags, he plays few of the hornpipes so popular in the middle and northern part of the state - partly because they were not common in the Ozarks when he was growing up and partly because of what he views as their limited local appeal.

There never was - other than Lonnie Robertson playing on the radio - there never was that many hornpipes around. A few of the real old-timers that was mostly about done before I come along, played some o' the old hornpipes in B flat and F. But in my time there wasn't any of 'em around, other than, like I say, hearin' Lonnie play 'em. 'Course he played Bob Walters; he'd learned all o' his tunes from Bob Walters, about. And that was the only hornpipe influence that we had. And they're just not that appealing to this part o' the country. They've got some intricate stuff in 'em and they're difficult tunes to play; but they just don't have the foot-stompin' ability - you know, to get people movin' - that our people want to hear. They'd rather hear just any simple little old tune you can think of than to hear the High Level Hornpipe, and that's the truth. So you'd just be wastin' all that good effort.

Of course, some of this is also a matter of personal taste, for Bob himself prefers tunes which "stir the blood," adding, "And it doesn't have be that fast, if it's got the right beat to it - got the right rhythm to it."

Bob is "not a great fan of contest fiddling," which he sees as exerting a conforming influence on old-time styles, because, as he comments:

Whatever wins a contest is gonna be what the young people's gonna pick up and play. And it's got the power of changin' the whole - nowadays, with the tape recorders and television and everything, it can change the whole country and make the whole country sound as one; there'll be no such thing as regional fiddlin' anymore, because whatever's winnin' on the contest circuit is what the young kids is gonna try to play. And what they seem to all be doin' is just gettin' more and more and more progressive all the time - until they're gettin' completely out of what we call old-time music.

Bob also complains that the vogue of "progressive styles" - or simply the desire to sound distinctive - is distorting the old- time repertoire:

People make such a big deal out of havin' so much license with tradition, but, you know - oh, everybody needs to do everything that they possibly can in order not to play a tune like somebody else. And they go to such lengths and put so much improvisation to it that, hell, you lose the tune completely. And you go through two or three generations like that, then where's the tune? The tune'll be completely gone.  A lotta the simpler things is the pretty things. Things that fit so well - I always think, every time I hear Fiddlin' Doc Roberts's version of New Money (sound clip) - it's the only version I've ever heard - from back then. That thing fits so perfectly that what can you do to a tune like that to make it better? When somethin' fits perfect, anything you do to it then can't do anything but make it worse. So I don't go along with this school o' thought of - I don't try to play different than somebody else. If I hear somebody that's playin' a tune that I consider logical, I try to play it just as near like that as I can, because I know when I get done I'm gonna be playin' it different anyway. So there'll be enough of a change there without me workin' at it - and losin' the soul of the tune.

A lotta the simpler things is the pretty things. Things that fit so well - I always think, every time I hear Fiddlin' Doc Roberts's version of New Money (sound clip) - it's the only version I've ever heard - from back then. That thing fits so perfectly that what can you do to a tune like that to make it better? When somethin' fits perfect, anything you do to it then can't do anything but make it worse. So I don't go along with this school o' thought of - I don't try to play different than somebody else. If I hear somebody that's playin' a tune that I consider logical, I try to play it just as near like that as I can, because I know when I get done I'm gonna be playin' it different anyway. So there'll be enough of a change there without me workin' at it - and losin' the soul of the tune.

Nor is Bob a fan of bluegrass styles, even when he admires the technical ability of individual musicians. For example, while he calls Scotty Stoneman a "great fiddler," he also found him "too much of an exhibitionist." "I've always liked just clean,straight fiddling," he explains. "I don't particularly care for bluegrass style, per se. But when they play just straight old mountain music, I like that. Which is where it all came from anyway, you know, to begin with: it's just jazzed up, souped up mountain music."

But while Bob has a very well defined aesthetic sense, he places no restrictions on his sources and is constantly adding new tunes to his repertoire from recordings or from tapes made at festivals. He has even been known, on occasion, to play an Irish polka.

I don't care where it's from. From Timbuktu or wherever; if it sounds good to me - if I like the way it sounds and like the rhythm and the structure of the tune - I'm only too happy to play it, if I can. But I like 'em all. And there's some great tunes from ever where. But, now, that doesn't mean that they'll sound like ... if I learn a Cajun tune, it won't sound like a Cajun tune: it'll sound like ... an old hillbilly playin' a Cajun tune is what it sounds like!

But it is as a square dance player that Bob is principally known, and he wouldn't have it any other way. "It's really not appreciated anywhere like it is here," he says, recalling compliments paid to him by visitors at a recent dance:

Now, they 'as honest enough, they didn't tell me I played the prettiest fiddle in the world or anything like that - but they did say there was no better to dance to. And that's the only accolades I'm after. If I can just make people dance - just make it to where they can't possibly sit still - that's my pay.

Bob has occasionally been criticized for playing too fast, although, as Alvie Dooms points out, it is the local dancers who dictate the tempo: "The square dancers used to just keep hollerin', 'Faster' and 'faster,' you know. And they wasn't half keepin' up then; but they wanted the music fast." Bob admits to setting a faster dance tempo than was common in his father's generation, when the dance style involved more of a shuffle than a clogging step. "But other than that, [my father] liked fast music. As he always said - Play me somethin' quick and devilish!" Bob ascribes the local preference for hard-driving music to the predominantly Scots-Irish ancestry of the area's inhabitants.

They're a passionate people. They work hard and they play hard - and if they dance, they want to dance hard. They want, like I said, the good, hard-drivin', foot stompin' rhythm: somethin' that winds 'em up, somethin' that stirs the blood up. As Alvie always says, "The fiddle wouldn't'a been called a devil's box if they hadn't a played anything but waltzes." But when you get these old foot-stompin' tunes, you see people start pattin' their feet, and they kinda get wound up. It's the very same thing on a lesser scale than voodoo - and voodoo drums - or religion. You take anything, and build it and build it and build it, and you get people wound up tighter 'n an eight-day clock. Like these old voodoo guys workin' up into hyperventilatin' and all that stuff. Or like a holy roller meetin', where they all get happy and go to shoutin' and rollin' on the ground and talkin' in unknown tongues.

Not surprisingly, the passion Bob attributes to the Scots-Irish temperament is one of his own most characteristic traits, evident in his independence of mind (he is a rare Democrat in a strongly Republican region) and the strength of his views on everything from music to world affairs. And it is his ability to communicate this passion to his listeners that makes his music so infectious. Ailene Adams, jig dancer and host of the McClurg music parties, comments:

One thing on Bob's music: if your feet's got any rhythm at all in 'em, there's just no way you can be still and not get up and move - because it's so perfect. And there's just no way you can sit and be still when you hear that: if your feet's got any rhythm at all, it just inspires you to get up and dance.

Such inspiration, of course, works both ways: "If you can buzz the dancers," says Bob, "then in return they buzz you.  Each feeds off the other ... It's a high that builds up." Yet it is not simply Bob's ability to inspire dancers which makes him such a highly respected fiddler. Long-time music partner Alvie Dooms praises Bob's playing for being "very easy to follow - and to hear." (The development of Alvie's guitar style seems to have fortuitously converged with Bob's fiddling: "When I got it to sound like I wanted it for rhythm, why, it's what he wanted.") Younger musicians especially admire the combination of lift and drive which Bob incorporates into his playing, and the subtle backbeat of his rhythmic style. St Louis fiddle player and maker Geoff Seitz notes that Bob's playing is remarkably "smooth," concluding that there is just "something special" about it. Other younger admirers include Chirps Smith, Chris Germain,and Gail Heil, who, not surprisingly, are all Midwestern fiddlers themselves, both in background and in style. Banjo-players find Bob a joy to play with because of the clarity of his rhythm and his contagious excitement for the music. In turn, Bob encourages revival musicians from the area, such as banjo-player Karen Kraft and fiddler Barbara Weathers, whom he appreciates for their interest in and feel for the music he loves. (Although two of Bob's three children play instruments, and one is an excellent church singer, none shares his passion for old-time music.)

Each feeds off the other ... It's a high that builds up." Yet it is not simply Bob's ability to inspire dancers which makes him such a highly respected fiddler. Long-time music partner Alvie Dooms praises Bob's playing for being "very easy to follow - and to hear." (The development of Alvie's guitar style seems to have fortuitously converged with Bob's fiddling: "When I got it to sound like I wanted it for rhythm, why, it's what he wanted.") Younger musicians especially admire the combination of lift and drive which Bob incorporates into his playing, and the subtle backbeat of his rhythmic style. St Louis fiddle player and maker Geoff Seitz notes that Bob's playing is remarkably "smooth," concluding that there is just "something special" about it. Other younger admirers include Chirps Smith, Chris Germain,and Gail Heil, who, not surprisingly, are all Midwestern fiddlers themselves, both in background and in style. Banjo-players find Bob a joy to play with because of the clarity of his rhythm and his contagious excitement for the music. In turn, Bob encourages revival musicians from the area, such as banjo-player Karen Kraft and fiddler Barbara Weathers, whom he appreciates for their interest in and feel for the music he loves. (Although two of Bob's three children play instruments, and one is an excellent church singer, none shares his passion for old-time music.)

Bob now lives on the farm where he was born (on land adjacent to where his father was raised), and is presently changing his operation over from dairy to beef production. While he finds farming "a hard life, in a way - and certainly not a get-rich-quick scheme," he prefers the independence it affords him, as well as the rural environment, whose peace and solitude accords well with the more contemplative side of his nature. (He once remarked that he got some of his best practicing accomplished when he was milking his cows, going over tunes in his head as he worked.) He also simply feels a strong attachment to his home and to his community: explaining his return from Iowa, he remarked, "I'd always been homesick, ever since the day I left." Bob is an avid outdoorsman, having hunted and fished since early childhood. Less predictably, perhaps, he is also a voracious reader, whose literary taste runs from Len Deighton to James Joyce. "I get hungry and thirsty when I see a new book," he explains, "I can't stand it till I see what's in it." More facetiously, he adds, "If I had the chance and the money to do just what I wanted to do, it would be hunt and fish, and play music, and read, and chase girls. Not necessarily in that order!"

Independent and self-sufficient on the one hand, Bob is also gregarious, articulate, possessed of a ready wit and a mischievous sense of fun, seeming to derive equal pleasure from his solitary and social pursuits, which, in the case of his music, happily converge. For Bob, that which makes life worth living is reflected not only in his musical activities (the social events upon which he thrives) but also in the music itself, which is so much a part of his identity. As he once commented, when asked how music fitted into his life, "Well, it would prob'ly be easier to say how does my life fit into music!"

Julie A Henigan - 15.6.98

Article MT021

The sound clips are taken from Bob's latest cassette The Way I Heard It, which, together with the earlier Rabbit in the Pea Patch, is available from: Bob Holt, HCR 71, Box 318, Ava, MO 65608, USA.

For the geographically challenged among us - the area in which Bob lives can be found by heading due West from Richmond, Virginia: cross the Appalatians, the whole of Kentucky and most of Missouri. The Ozarks lie SW to NE across the state. You are almost half way across the USA.

This article first appeared, in very similar form, in the American magazine Old-Time Herald:

P.O. Box 81812, Durham, North Carolina 27707, USA. E-mail: oth@mindspring.com

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 18.10.02

whose fiddle playing has become synonymous with dance music in a part of the Ozarks where (despite the proximity of the country music mecca of Branson) traditional square dancing has managed to hold its own as a community recreation. Throughout the winter there is at least one square dance a weekend, either in Douglas County or neighboring Taney County; and the fiddle player is nearly always 'Holt'.

whose fiddle playing has become synonymous with dance music in a part of the Ozarks where (despite the proximity of the country music mecca of Branson) traditional square dancing has managed to hold its own as a community recreation. Throughout the winter there is at least one square dance a weekend, either in Douglas County or neighboring Taney County; and the fiddle player is nearly always 'Holt'.

During this period, Bob worked in a cabinet factory and later attended barber school, playing on weekends for dances or at nightclubs in a country band. Here he began his long-time association with guitarist and singer Harley Newberry (whom Bob calls the best country singer he's ever heard "runnin' around loose") and his wife Betty, who played bass with the band. According to Bob, the only thing that "justified" his presence in the band were the several square dances he would play during the course of each performance. Later, when bluegrass had begun to supersede the older country bands, Bob joined a group which played bluegrass and "a little folk." But while he appreciated the skills of his fellow musicians and enjoyed performing with them, such contexts had their drawbacks for Bob.

During this period, Bob worked in a cabinet factory and later attended barber school, playing on weekends for dances or at nightclubs in a country band. Here he began his long-time association with guitarist and singer Harley Newberry (whom Bob calls the best country singer he's ever heard "runnin' around loose") and his wife Betty, who played bass with the band. According to Bob, the only thing that "justified" his presence in the band were the several square dances he would play during the course of each performance. Later, when bluegrass had begun to supersede the older country bands, Bob joined a group which played bluegrass and "a little folk." But while he appreciated the skills of his fellow musicians and enjoyed performing with them, such contexts had their drawbacks for Bob.

At a time when clawhammer players were already becoming rare in the Ozarks (the majority played chordal backup), Node Holt played (according to Bob) "just as near note for note as you could possibly play with a banjo. I learned a lotta tunes from his banjo playin', and when I later heard 'em played on the fiddle, I didn't have to change 'em much." Although his mother's brother, Bill Thompson, also played fiddle, Bob learned few tunes from him because he lived too far away for frequent encounters, in Rogersville, Missouri. He did, however, "get the basics" of several tunes from him - as well as "the idea for" cross-key fiddling.

At a time when clawhammer players were already becoming rare in the Ozarks (the majority played chordal backup), Node Holt played (according to Bob) "just as near note for note as you could possibly play with a banjo. I learned a lotta tunes from his banjo playin', and when I later heard 'em played on the fiddle, I didn't have to change 'em much." Although his mother's brother, Bill Thompson, also played fiddle, Bob learned few tunes from him because he lived too far away for frequent encounters, in Rogersville, Missouri. He did, however, "get the basics" of several tunes from him - as well as "the idea for" cross-key fiddling.

Each feeds off the other ... It's a high that builds up." Yet it is not simply Bob's ability to inspire dancers which makes him such a highly respected fiddler. Long-time music partner Alvie Dooms praises Bob's playing for being "very easy to follow - and to hear." (The development of Alvie's guitar style seems to have fortuitously converged with Bob's fiddling: "When I got it to sound like I wanted it for rhythm, why, it's what he wanted.") Younger musicians especially admire the combination of lift and drive which Bob incorporates into his playing, and the subtle backbeat of his rhythmic style. St Louis fiddle player and maker Geoff Seitz notes that Bob's playing is remarkably "smooth," concluding that there is just "something special" about it. Other younger admirers include Chirps Smith, Chris Germain,and Gail Heil, who, not surprisingly, are all Midwestern fiddlers themselves, both in background and in style. Banjo-players find Bob a joy to play with because of the clarity of his rhythm and his contagious excitement for the music. In turn, Bob encourages revival musicians from the area, such as banjo-player Karen Kraft and fiddler Barbara Weathers, whom he appreciates for their interest in and feel for the music he loves. (Although two of Bob's three children play instruments, and one is an excellent church singer, none shares his passion for old-time music.)

Each feeds off the other ... It's a high that builds up." Yet it is not simply Bob's ability to inspire dancers which makes him such a highly respected fiddler. Long-time music partner Alvie Dooms praises Bob's playing for being "very easy to follow - and to hear." (The development of Alvie's guitar style seems to have fortuitously converged with Bob's fiddling: "When I got it to sound like I wanted it for rhythm, why, it's what he wanted.") Younger musicians especially admire the combination of lift and drive which Bob incorporates into his playing, and the subtle backbeat of his rhythmic style. St Louis fiddle player and maker Geoff Seitz notes that Bob's playing is remarkably "smooth," concluding that there is just "something special" about it. Other younger admirers include Chirps Smith, Chris Germain,and Gail Heil, who, not surprisingly, are all Midwestern fiddlers themselves, both in background and in style. Banjo-players find Bob a joy to play with because of the clarity of his rhythm and his contagious excitement for the music. In turn, Bob encourages revival musicians from the area, such as banjo-player Karen Kraft and fiddler Barbara Weathers, whom he appreciates for their interest in and feel for the music he loves. (Although two of Bob's three children play instruments, and one is an excellent church singer, none shares his passion for old-time music.)