Although he died some thirty years ago, Edden Hammons has not been forgotten. He is considered by many to have been one of the finest traditional West Virginia fiddlers of all time, and tales of his musical exploits and eccentric lifestyle flourish among the inhabitants of mountainous east central West Virginian, where he lived from about 1874 to 1955. As Fleischhauer and Jabbour's study The Hammons Family ![]() 1 has revealed, Edden was just one of an extremely dynamic mountain clan that migrated into West Virginia from Kentucky at the advent of the Civil War.

1 has revealed, Edden was just one of an extremely dynamic mountain clan that migrated into West Virginia from Kentucky at the advent of the Civil War.  Like nearly all of the Hammons men, Edden's father, Jesse, was a renowned 'woodsman', as he was labelled by a 1900 federal census taker, and vivid descriptions of his lifestyle and exploits survive in both memory and print. To neighbour and journalist Andrew Price, old Jesse epitomised mountaineer life.

Like nearly all of the Hammons men, Edden's father, Jesse, was a renowned 'woodsman', as he was labelled by a 1900 federal census taker, and vivid descriptions of his lifestyle and exploits survive in both memory and print. To neighbour and journalist Andrew Price, old Jesse epitomised mountaineer life.

In West Virginia, the fur [far] Mountains are the ones that rise to majestic heights and are clothed in the sombre hues of the spruce. Some idea of this wilderness can be obtained from the experience of Jesse Hammonds, a patriarchal hunter and trapper living in this forest.Jesse's wife, Nancy Hicks, was a native of Indiana. According to family legend she had travelled to Kentucky in a covered wagon at age eleven, the child bride of a forty-three-year-old man whose name can no longer be recalled. It is presumed that this man died prior to Nancy's marriage to Jesse about 1852. Jesse and his wife had seven children who survived infancy- four boys, Paris, Peter, Cornelius (Neal), and Edden, and three girls, Dice, Jane, and Mary. Like their father, the three elder boys gained considerable fame for their skill in the forest, and phrases like 'famous woodsman and hunter' garnish the obituaries of all. The three are also remembered among their descendants as being fine fiddlers, though there is little doubt that in this regard, the youngest boy, Edden was superior to the rest. Family tradition holds that young Edden's ability was recognised and encouraged at an early age and that the boy was largely spared his share of the burdens of frontier living as a result. Edden's daughters, Alice and Emma, agree with Andrew Price's depiction of their father as a consummate fiddler and an idle 'dreamer'. They consider his status as the youngest, 'the baby of the family,' to have been at least partially responsible.When the war clouds began to lower on his house in the fifties, Hammonds refugeed from Kentucky, seeking a safe retreat, and settled on Williams River, and for thirteen years not a stranger darkened his door. The great Civil War was fought without his knowing anything about it. The county, Webster, in which he lived, formed an independent government, neither recognising the North nor the South, and elected a governors and is still referred to in State conventions as the 'Independent State of Webster'.

Old Jesse raised a large family of sons, who took to the woods and lived the life of the Indian. Their wives and children raised a little corn, but the men pride themselves on the fact that they never worked and never will. They know the woods thoroughly and are the best of hunters and fishers, dig ginseng and find bee trees. They are a thorn in the flesh of the sportsmen, for they kill to sell, and last year when the headwaters of Williams River showed good results from the planting of a hundred thousand Government trout, they spent the summer fishing for these small trout to sell to the lumber camps. They owe their immunity to the fact that they have held possession of the lands of a big land company and know the corner trees and would be invaluable were its titles ever attacked.

Like the Indians the Hammonds of Bug Run have been forced on until they are now located in the fringe of woods in the south side of the tract and can go no farther.

I one time saw Neal Hammonds kill a deer. We were walking down the river from our camp at the mouth of Tea Creek deer hunting. Just as we reached the stand at the Big Island a fawn jumped into the river in a panic of fear, fleeing from its stepfather, no doubt, and once on the other side the little fellow hit the runway as fair as if a pack of hounds were after it. I took no action, but Neal threw his rifle into position and shot the top of the fawn's head off as it ran. It fell dead and proved to be an unusually large buck fawn.

The Hammonds are not educated, except in woods lore. They may know that there are such accomplishments as reading or writing, but these they have never hankered after. Yet one of the boys, Edn, is a great musician. His artistic temperament has made more or less a dreamer of him and detracted from his ability as a bear hunter. He takes to the calmer joys of fishing and 'sang' digging, and he repudiates the idea that his name is Edwin or possibly Edmund and gravely informs you that his name is simply 'Edn, an' nothin' elst'.

Edn's first attempt in music was with a fiddle made from a gourd. He progressed and he secured a store bought fiddle and there is no disputing the fact that he can draw exquisite harmonies from this. He has composed several melodies and he has given them names, the most notable one being called 'Hannah Gatting fish!' He explained the music to me one time and I must confess that it seemed as real to me as any high grade composition. I recorded it, one day when Edn came to my house on a blank wax gramophone disc and have reproduced it often since, down to the resounding patting of the violinist's foot on the floor. A man from Pittsburg told me it was very fine and expressive, and that he believed it to be an entirely new and original piece of music.

2

Emma: No responsibility. He was cared for and looked after and petted by the older ones, you know, his siblings. Everybody just took care of him and petted him, and didn't teach him responsibility at all.Whether because of immaturity or musical passion, Edden refused to lay his fiddle down 'like most men did' as he grew older and was faced with supporting a family. Coupled with his inherited sense of restlessness and the increasing difficulty of foraging to survive, Edden's values and goals made life somewhat difficult for those around him. His first wife, Caroline Riddle, whom Edden married in 1892, left her husband after only three weeks of marriage. His unwillingness to support her is generally deemed responsible. Family members humorously repeat Edden's alleged response to her ultimatum to quit playing the fiddle and go to work: ' 'Pon my honour, I'll lay my fiddle down for no damn woman.'

Alice: That was his byword, ' 'Pon my honour', and he was serious when he'd say that you know. He was an old guy that, that, he didn't lie now, he was pretty truthful - but I guess you know at that danged time, there wasn't too much work for anyone. Somebody may have had a job like logging job or something ... see he was the baby one of their family and they even after he was married he'd go back home and they'd keep candy and stuff for him you know. They babied him and he didn't have to work, I guess. They didn't make him. So I guess that he put in his time playing the violin, fishing and hunting.According to original case records in the Webster County courthouse, Edden's and Caroline's marriage was not legally dissolved until 1897. On April 1 of that year Edden was granted a divorce on the grounds that his wife left him after three weeks of marriage for no apparent reason. Caroline was not present to contest or provide another explanation. Ten days after the divorce was granted Edden married Elizabeth Shaffer. Emma reports that Edden's second wife received fair warning of her father's shortcomings.

I remember Mom telling me that my father's grandmother ... she'd get my mother by the hand and pull her over and whisper to her and she'd say, 'Now Bett,' it was my dad's grandmother, 'cause she'd say, 'Now don't marry Edden, he ain't no good.' She'd whisper to my mother, 'He won't make you a good husband.'Despite such warnings Betty married Edden on April 10, 1897. By all accounts their marriage proved to be one of great love and devotion which endured until Betty's death in 1954.

While Betty bore the surname Shaffer, Emma explains that she was actually a Hammons:

While Betty bore the surname Shaffer, Emma explains that she was actually a Hammons:

Her father, John Hammons, was a brother to my father's father, Jess Hammons. They were brothers, and my grandmother, my maternal grandmother, and my grandfather John separated, for what reason I don't know, but she raised my mother and my Aunt Martha by her maiden name Shaffer, and they grew up that way and didn't use the name Hammons.Edden and his new wife raised seven children: Nancy Rebecca (b. 1898), William Smith (b. 1902), Jesse James (b. 1904), Sarah Irene (b. 1906), Henry (b. 1908), Martha Alice (b. 1914), and Emma (b. 1918). Three are presently living: Smith, Alice, and Emma.

Like their forebears, Edden and his family led a somewhat nomadic existence, generally settling in one place only long enough to raise a crop. Smith recalls living at several locations along the Williams River from his birth in 1902 until about 1914, when the family moved up into Randolph County, occupying several residences over six or seven years. Emma, born in 1918 recalls no fewer than fourteen moves during the eighteen years she lived at home, beginning in l922 with the family's return to Webster County, where they took up residence at the White Oak fork of the Williams River. Two years later the family was living at Tom Myer's farm in Bolaire, five miles south of Webster Springs. The following year they removed to Chillicothe, Ohio, where daughter Nancy Rebecca and her husband had settled down and reported favourable economic conditions. Edden's surviving children remember Ohio as being generally 'too flat' for their father's tastes. They consider the family's five or so years there to have been inordinately restless, with changes in residency 'every six months or so'. About 1930 the family returned to West Virginia and settled for two or three years on Hills Creek near Hillsboro in Pocahontas County. A series of annual moves within the same county took them to Stamping Creek, Viney Mountain near Bald Knob, Greenbrier River near Watoga, Woodrow, Dunmore, Blue Lick Creek, back to Hills Creek, and then back to Stirling Creek about 1940. The following year Emma was able to buy her parents a home in Webster County between Webster Springs and Bolaire, a sort of retirement present, as she explains it. The two stayed there a while, but the area proved a little too urbanised for Edden's taste, and when people began to stop by 'all hours of the night' to hear him play the couple traded the property for a cabin situated on a remote thirty-acre tract of land on Grassy Creek. In the early fifties they vacated this property in favour of the Pocahontas County home of Fred Ruckerman on Blue Lick. It was here that Betty died in 1954. Edden's final year was spent with daughter Alice in Rennick. His death on September 7, 1955, is attributed to congestive heart failure.

Edden managed to support a large family through a variety of means. Food for the table was provided by subsistence farming, hunting, fishing, and to a lesser extent animal husbandry. Nuts, berries, and other fruits of the forest provided an important supplement. Emma explains that while her father looked after field crops - generally corn and hay- the vegetable garden which provided over half the family 's sustenance was her mother's responsibility. Produce for winter consumption was canned, dried, or preserved in other ways. Apples and potatoes were either pared, quartered and strung up to dry, or holed in a shallow pit lined and covered with hay or leaves in which they remained fresh for several months . The family found shelter in vacant dwellings belonging to relatives or local farmers who eagerly offered a roof to anyone willing to feed the livestock or just 'keep an eye on the place'. Cash for kitchen supplies, hunting equipment, fiddle-strings, and other 'store-bought goods' was derived from a variety of activities.

Emma: He whittled axe handles, he played for dances, different things. He picked up money that way. Ginseng, he'd get money that way. It was against the law but he would kill squirrels, turkeys and sell them, or fish - he always had a couple of dollars in his pocket somehow.Emma disputes Andrew Price's claim in his sketch of Jesse Hammons that the family was exempt from fish and game laws and recalls that her father's only immunity rested in his cleverness.

There was a game warden named Gay, in Pocahontas County, and my father, he knew my father well, and he would try his best to catch my father fishing, and my father could catch more trout than anybody I ever saw. I mean you could go and fish before my father got to the stream and maybe you couldn't catch a fish, and my father could come right along behind you and catch, he never fooled about the limit or size of the fish, but he just - now trout now, he wouldn't fool with anything else.Despite their disregard of regulations, Emma is quick to point out that her family's wildlife harvest was governed by a strict code of 'natural' laws and a profound respect for their habitat.But this Lewis Gay, he tried to catch my father, and you know how he would outsmart Gay, he ginsenged, and he fished and he combined this, maybe hunt, all three at the same time, and he would have his line wrapped around just a little stick, his hook and line, he'd wrap it around and stick it in his pocket, take his gun and his ginseng bag and away he'd go, maybe stick a biscuit or two in the bag, and he'd get along a good fishing spot and he'd cut him a pole, a green pole, find him a lizard or a hellgrammite or whatever, and he'd bait his hook, and he'd set his pole, hide it in the bushes like, and set his pole and then he'd go sanging and hunting, and then he'd come back to his pole, he'd sneak back you know, in the woods and peep around and if he saw that line wiggling, he knew he had a fish on there. So he'd look all around and nobody's around, he'd go and take that fish off and put it on a string and put it in the water, set his pole and go on about fishing. And Lew Gay tried for years. He said, 'Honest to God,' he said, 'I'd be coming up over one mountain, and Edden would be going over the next one.' He said, 'I couldn't catch that man for nothing!' And he would, I mean, that was his life's desire to catch my father.

So he said finally he was going up this creek - out of season, fishing was - he was going up this creek and he saw this pole setting and he said, he said to himself, 'That is Edden's just as sure as shooting.' So he hid and sure enough he heard a little rattle in the bushes and he - had himself real hid - and here comes Dad, and Dad was looking all over - nobody in sight and he goes up and picks his pole up to take off the fish and Gay walks out with his gun trained right on him. 'Well, Edden,' he said, 'this took me,' I believe he said, 'nine years, but,' he said, 'I finally got you ... This is a big day in my life.'

When they dug the sang they would always plant the berries back, they didn't just throw 'em away, and they never killed a deer that was pregnant, they could always tell and then usually the time of year - or squirrels, they would never shoot a squirrel in the time when they'd be carrying their young, the females - they were careful about that ... My father one time didn't know it but he killed a, a bear, ah, they call 'em 'she bears', a female, and she had two cubs, and he didn't know it until after he'd killed the bear and he saw the little cubs coming around to where he was skinning the bear. So he brought the cubs home and we raised them - well, I don't think I was born yet - and those cubs were like dogs, I mean they grew right good size, and ah, they, my father and mother, they got so big they got a little concerned about the children, you know, and they gave them away and finally the two bears wound up in the zoo, they'd been passed from one to the other ... And then I remember them telling one story, I, I don't believe it was my grandmother, but it was an aunt. Her husband killed a deer and it had a little fawn and they didn't know it and when they found it out they brought it home, and they didn't have milk. They didn't have a cow to feed the little fawn, and my grand, it wasn't my grandmother, it was an aunt or somebody, she nursed it, breast fed it and it grew up ... They said that fawn would try to kill the baby. The baby would be nursing and it would come up and paw it with its hoof. Fight it away from the breast.Some of Edden's fish and game catch may have gone to wholesale grocery dealers such as Myers Provision Company of Wheeling, West Virginia, which advertised each fall in the Webster Springs Webster Echo from 1904 -1908 that 'we will buy all kinds of game, bear, deer, turkey, pheasant, quail, rabbit, squirrel, racoon, opossum and anything else in the game line ... 75c each for choice pheasants.'

About the same time the Webster Echo also reported that 'The Hammonds, who make their living by catching fish and selling them for 35 cents a pounds had recently assisted a trio of Maryland 'sportsmen(?)' in securing over 1,000 trout. ![]() 4

4  Itinerant camps formed by labourers employed by the logging operations which converged upon the region shortly after the turn of the century afforded another handy market, not only for food but for commodities like axe handles and even music.

Itinerant camps formed by labourers employed by the logging operations which converged upon the region shortly after the turn of the century afforded another handy market, not only for food but for commodities like axe handles and even music.

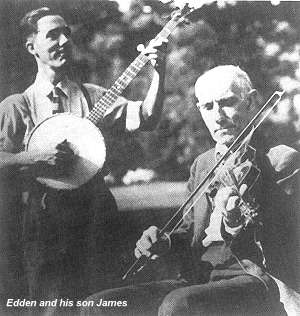

Fred Roberts, a relative to the Hammonses through Edden's uncle Cornelius Roberts, remembers regular visits by Edden and his son James to camps in which he lived and worked in the 1920s. He recalls that on rare occasions a fiddler was hired to play for a dance or celebration, but more often than not they would come around in the evening, play awhile and pass the hat. Edden's nephew Sherman remembers his uncle's visits to the crude camp taverns.

Well, you know, Edden, that was when Camp Four was in here, you know, and just built up old pens, that's the way they lived, and daub it up with moss and part of the time didn't have no floor in it, you know, and then you could order whiskey, you see you could order whiskey ... so Edden would go around the camp up there you know and play.Alice reports that her father's fee for playing at dances or weddings ranged from five to ten dollars, payable in cash or some other commodity - coffee or perhaps a ham. Fiddle contest winnings also contributed to Edden's substantial but sporadic musical income.

Emma describes yet another lucrative source of hard money.

John Cuthbert: Now, how much could have moonshining contributed to ... ?Emma says that her father was generally clever enough to stay ahead of the revenuers, but both she and Sherman remember one occasion when he was arrested for 'transporting'.Emma: Well, that did a lot ...

How many jugs, how many gallons could he make in one run?

I think, it seems to me like fifteen gallons, and the way he hid it, see, as I told you earlier, my father was uneducated but he wasn't dumb by a long shot. And he'd be a, catch the time when the wind would blow away from the neighbourhood, where, you know, mash can be smelled a long ways ... Well, it's got an odour that you can't mistake - not a bad odour, but you know what it is when you smell sour mash - and he would build a fire like he was clearing off new ground for a corn field or planting of some kind. He'd pile that brush on top of his mash barrel, to heat. you know it has to get hot ... and nobody knew that he was making whiskey, while he was clearing off, he cleared a lot of the ground for the farmers just a-making moonshine.

Now where would he sell most of this?

People would come ...

People that lived in the county?

Right, or counties away. But they knew where to get the good, you know a lot of people, well, I'm sure you're aware of, ah, they put lye in it just to make it hot, just to sell it, and it would kill you. I know a lot of people died from it. But my father would double it couple or three times, you know, run it through, that's called doubling it.

To improve the alcohol content?

And you know how you can tell if you're drinking good moonshine from bad ... pour it in a teaspoon, then strike a match and light that, and if all that burns then you've got pure whiskey. But if only a little bit of it burns and the rest you got in that spoon is green, stay away from that, it's poison.

Well, he had a carrying case, I guess he had five or six gallon in it, and he had my brother James along, and they were on the train, on their way to Cumberland - I, I don't remember if it was the conductor or who, tipped him off that the revenuers had boarded the train, and he gave the suitcase to my brother, who was about seven years old - I don't know why he thought they would buy that, but they got him and took him to jail and they, I guess he had to lay the fine out or something. But he was in there one hundred thirty-seven days, he told me that many times, 'one hundred thirty-seven days and nights.'Despite diverse sources of income the family experienced plenty of hard times which are perhaps a bit too hastily blamed on Edden's general distaste for working.J C: And this was in Elkins?

I'm sure it was Elkins.

So what was his jail stay like?

Well, he entertained all the prisoners with his fiddle. They brought his fiddle in and he played for the inmates, kept them all entertained, till he, just about a week or two weeks before his release they made him trustee and he was out cutting the grass and taking care of things, and one of the prisoners called down to him and told him to run and he said 'No, I've only got a little while left, I think I'll just stay,' and he [the prisoner] said, 'I'm gonna put a dollar in your hat and drop it down if you'll go,' and they dropped it down and my father took off. Then he realised how foolish he was and so he came back and I don't suppose he got fined for it or, you know, had his sentence increased ...

What do you suppose his motive was in asking him to run?

He needed him around there to entertain them, is all I can figure out.

According to turn-of-the-century reports of the West Virginia Department of Agriculture, some 80 per cent of the county's wage earners claimed agriculture as their principal occupation about 1900, yet these reports indicate that most farming was conducted on a small scale which is more accurately considered subsistence than commercial. ![]() 6 Indeed, the fact that the department reported the existence of well over 1,000 farms in 1900 in a county with fewer than 9,000 inhabitants suggests that the term 'farm' was applied broadly enough to include the many households that lived off the land in one way or another as the Hammonses did.

6 Indeed, the fact that the department reported the existence of well over 1,000 farms in 1900 in a county with fewer than 9,000 inhabitants suggests that the term 'farm' was applied broadly enough to include the many households that lived off the land in one way or another as the Hammonses did. ![]() 7 Edden himself is listed as a farmer in the 1910 census.

7 Edden himself is listed as a farmer in the 1910 census. ![]() 8 His children recall that annual corn crops, eggs, young livestock, and occasionally other surpluses provided an important source of barter for supplies and other store goods . Yet most of what the family raised was consumed on the premises. Reports of the state extension service indicate that although off-farm income became increasingly important, subsistence farming on this level, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and foraging, remained a generally viable and popular means of provision until well into the twentieth century.

8 His children recall that annual corn crops, eggs, young livestock, and occasionally other surpluses provided an important source of barter for supplies and other store goods . Yet most of what the family raised was consumed on the premises. Reports of the state extension service indicate that although off-farm income became increasingly important, subsistence farming on this level, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and foraging, remained a generally viable and popular means of provision until well into the twentieth century. ![]() 9

9

Such a lifestyle afforded ample time for leisure activities. Pocahontas Times editor Calvin Price believed that the average person on farms in neighbouring Pocahontas County worked no more than sixty days per year. ![]() 10 In regard to farming, Edden's restlessness might well have proved more detrimental to the family's welfare than his laziness. Clearing ground and establishing farm land is difficult work, and rather than enlarging and improving his farm as the years went by, Edden apparently kept starting over as the family moved from place to place.

10 In regard to farming, Edden's restlessness might well have proved more detrimental to the family's welfare than his laziness. Clearing ground and establishing farm land is difficult work, and rather than enlarging and improving his farm as the years went by, Edden apparently kept starting over as the family moved from place to place.

It was perhaps his reluctance to seek seasonal day-work off the farm as others did which lies at the root of his reputation for laziness. Few of his neighbours could entirely resist the cash afforded by work in the lumber industry, which gradually grew in importance to local economics as the region's primordial bounty subsided in its path. Edden's refusal to participate in this work likely confirmed the logging community's stereotypical view of all fiddlers and contributed heavily to this aspect of the Hammons legend. ![]() 11 Indeed, Edden's laziness is just one of many alleged quirks and idiosyncrasies which form the nucleus of a rich store of colourful anecdotes traded back and forth among family and friends with great pleasure. Along with his shortcomings as a provider, Edden's backwoods naïveté and 'therapeutic' excuses for drinking are common themes. Emma tells a searing anecdote about the time her father applied mustard salve to his haemorrhoids. Cousin Dona Gum remembers Edden's response one time when asked if he could sit and fiddle awhile on the davenport: ' 'Pon my honour, let me see it, how many strings has it got?' Such stories invariably include emphatic impressions of their subject's gestures and speech - ' 'Pon my honour, I can't use the bow without I get a drink.' Altogether, such stories depict a character who fits perhaps a little too neatly into the 'hillbilly' mould to be real, yet those who remember Edden insist that there is at least a kernel of truth in every one of them. Emma questions the veracity of her cousin Dona Gum's 'davenport' incident - 'It's sort of like that one, 'Why, Mr Hammons, do you know your fly is down?' 'No, but if you can hum a few bars maybe I can play it.' A person could tell a story like that on anybody.'

11 Indeed, Edden's laziness is just one of many alleged quirks and idiosyncrasies which form the nucleus of a rich store of colourful anecdotes traded back and forth among family and friends with great pleasure. Along with his shortcomings as a provider, Edden's backwoods naïveté and 'therapeutic' excuses for drinking are common themes. Emma tells a searing anecdote about the time her father applied mustard salve to his haemorrhoids. Cousin Dona Gum remembers Edden's response one time when asked if he could sit and fiddle awhile on the davenport: ' 'Pon my honour, let me see it, how many strings has it got?' Such stories invariably include emphatic impressions of their subject's gestures and speech - ' 'Pon my honour, I can't use the bow without I get a drink.' Altogether, such stories depict a character who fits perhaps a little too neatly into the 'hillbilly' mould to be real, yet those who remember Edden insist that there is at least a kernel of truth in every one of them. Emma questions the veracity of her cousin Dona Gum's 'davenport' incident - 'It's sort of like that one, 'Why, Mr Hammons, do you know your fly is down?' 'No, but if you can hum a few bars maybe I can play it.' A person could tell a story like that on anybody.'

Still she admits with a chuckle that such jokes make good stories and certainly do fit the pattern, and it is clear that she takes great pride in her father's position in local folklore.

Several tales centre on Edden's belief in superstitions and the supernatural. Alice reports that her father, while not a deeply religious man, faithfully observed the Sabbath in his own way: the fiddling stopped when the clock struck midnight on Saturday evening. Currence Hammonds of Huttonsville, West Virginia, Edden's nephew and musical protégé while the family was living in Randolph County, recalls the consequences of one prolonged Saturday-night performance.

Currence: You know the last time I played with that feller, my uncle, at a dance, was me and him and old Ed Long, and ah, that, oh I can't think of his name. They lived down there right up from that old Ed Long. We went over to Father's Creek. There was a fellow that lived there. I forget their name. They lived there. I never was over but oncet or twicet. And we played a piece there. We went over on Saturday night, to play for a dance. But now Edden, he never would play till twelve o'clock on Saturday night. Twelve o' clock come and Edden quit. Yes sir, he wouldn't play. But they kept on to play for another set, you know, it was after twelve o' clock. And now Edden said, 'Listen,' he said, 'I don't play after twelve o'clock for dances.' He said, 'Just to sit and listen at I'll play some.' 'Oh, it won't hurt you tonight, play for another set, we'll give you an extra dollar!' 'Well,' Edden said, 'I'll play for another set.' He played for it, me and him, I was playing the banjo.We was coming back home, and was all a-riding horses, horseback, from old Father's Creek back to Ed Long's. And we got right on top of the mountain, there's an old skidder there that they skidded logs from down in there up the top of the hill. Well, just as we got to the top of that, right on top of the mountain - I can show just right where it was at - Edden, him and Ed, was in front of me with Worthy Dicks, that's who it was, Worthy Dicks. Me and Worthy was behind them a-riding, you know. Edden all at once just stopped and said, 'Looky there! ' Ed Long he was about drunk. Oh, he was so drunk, he couldn't hardly set on the horse. 'Now a what do you see, Edmund?' He called him Edmund all the time. Edden said, 'Look back yonder.' And I'd swear that there was a red streak went right through the sky, but it went thisaway, right across like that. And it wasn't over the wide, when we saw it. And it kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger and just now, I'm a-telling you it widened out as wide as this house. Clear across the sky. And you could see anything in that strip that you looked for ... you could see people there, you could see anything, in that light. And we just set there. Nobody never said a word. Just set and looking at it. And just now it just started, like that and it went clear back together, and when it went together, something went 'Boom!' Just like you know, thunder, low thunder. Nobody never said a word. We just started on with the horses and going down the hill. We wasn't a-talking any. And this fellow said, 'Edmund, did you ever see anything like that?' 'No my honour,' he said, 'I told you fellers to not play for a dance on Sunday night.' Now he said, 'Now I don't care if you give me twenty-five dollars the next time, I'll never play.'

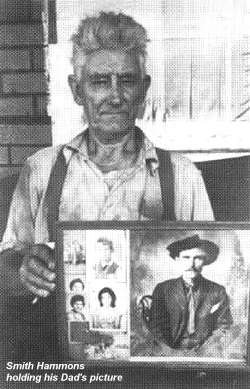

Edden's children find it difficult to think of a member of the family who was not musically inclined in one way or another. Virtually all of the Hammons men played the fiddle to some degree. Edden's uncle Pete Hammons, who moved to Montana about 1910, is considered to have been about the best of his generation of family fiddlers, which included all of his brothers, one of whom was Edden's father, Jesse. Smith credits his grandfather with having provided Edden's earliest instruction as well as his first fiddle - a crude instrument fashioned out of a crookneck gourd.

Edden's children find it difficult to think of a member of the family who was not musically inclined in one way or another. Virtually all of the Hammons men played the fiddle to some degree. Edden's uncle Pete Hammons, who moved to Montana about 1910, is considered to have been about the best of his generation of family fiddlers, which included all of his brothers, one of whom was Edden's father, Jesse. Smith credits his grandfather with having provided Edden's earliest instruction as well as his first fiddle - a crude instrument fashioned out of a crookneck gourd. Smith: Why, he made the fiddle for him when he was just a boy, I don't know how old he was, just a boy, and anyhow he learned him to play what he knew, for he didn't have nobody to learn him much, you know, well my Grandfather could play a little but not that good. But old Uncle Pete was good you know, he's my grandfather's brother, and he was good, so he taught him how to play and learned him a lot of different tunes - old-timers, and he got pretty good on that gourd fiddle, I reckon. He must have been, so that this man come along one day and I reckon my grandfather knew him, I don't know, so he stopped in and he said, 'Well, play us a tune on your fiddle,' he said, 'I see you got one.' Well he got it out and played him a tune or two. 'Now' he said, 'Edden,' Grandpa said, 'now Edden get your fiddle and play him a tune.' Dad, he went and got his old gourd fiddle and played him a tune or two on it and he said, 'Let's see that.' Well, Dad handed it over to him and he looked it over, you know, just wasn't over that long, an old crookedneck gourd, you know, he made it out of. 'Well,' he said, 'I don't have any more use for a fiddle,' he said, 'here you can have mine,' and he just reached it to him. That was the first factory one he ever owned.The Hammonses can no longer remember the older fiddler's name, yet West Virginia author Sampson Newton Miller recalls a similar encounter between the youthful Hammons and a man named Bernard Hamrick; the setting is somewhat different but the outcome appears to have been about the same.

About 1899 on the Fourth of July at Webster Springs, there was scheduled a platform dance and picnic near the old Salt Sulphur Spring.Smith believes that it was his great-uncle Pete who taught Edden more about fiddling and fiddle tunes than anyone else, though the art is far too prevalent among the Hammonses to attribute any family member's musical education to one individual. Family members also recognise the influence of various other east-central West Virginia fiddlers whom Edden knew and often encountered at dances, festivals, and other public events. Smith recalls that fiddle contests in particular provided an important forum for the exchange of tunes and techniques among regional fiddlers. He estimates that his father participated in perhaps five or ten contests a year, and rarely came away with less than the first prize.As a boy, I distinctly remember this event. Whoever had charge of the dance had employed Bernard Hamrick to play for it. 'Burn', as he was familiarly known, brought his violin to the platform about two hours before the dance was to start. He tuned his fiddle and began to play. People flocked in from everywhere. 'Burn' played on a few pieces and quit. People cheered and cheered, but 'Burn' wouldn't play any more.

Jesse Hammons, father of Edden, said 'Mr Hamrick, let my son play a tune or two.' After a great deal of persuasion, 'Burn' let the lad of nine have the violin. Edden tuned it and started playing the fiddle on his left shoulder. He played so well and the people began to cheer till you could scarcely hear anything else. 'Burn' got peeved at what had happened and he gave Edden his violin and went home. So there was no dance that afternoon.

13

Newspaper clippings in the possession of family members and friends or gleaned from local newspapers bear out such claims and provide hard evidence of Edden's contest successes against a notable list of talented performers - Tom Dillon, Gander Digman, Gus McGee, Jasper Trent, Woody Simmons, Oscar Wright, and Jack McElwain to name a few. Perhaps Edden's most distinguished adversary was Lewis 'Jack' McElwain (1856-1938), regarded by many as the premier fiddler in the state of West Virginia around the turn of the century. McElwain was a self-taught lawyer and a justice of the peace in and around Erbacon, West Virginia. His contest credits included a first-place finish at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893.

Newspaper clippings in the possession of family members and friends or gleaned from local newspapers bear out such claims and provide hard evidence of Edden's contest successes against a notable list of talented performers - Tom Dillon, Gander Digman, Gus McGee, Jasper Trent, Woody Simmons, Oscar Wright, and Jack McElwain to name a few. Perhaps Edden's most distinguished adversary was Lewis 'Jack' McElwain (1856-1938), regarded by many as the premier fiddler in the state of West Virginia around the turn of the century. McElwain was a self-taught lawyer and a justice of the peace in and around Erbacon, West Virginia. His contest credits included a first-place finish at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. The Old Fiddlers contest at the opera house last night drew forth a very good crowd considering the fact that a night session of court was being held. There were only three contestants for the prizes offered. Those contesting were L J McElwain, of Erbacon, Webster County, who walked 75 miles through the country to get here in time, Edmond Hammonds, of the Three Forks of Williams river, and W S Darnell, of Bartow. The judge selected by McElwain was ruled out because he arrived a few minutes late, but before time for the contest to begin, and another judge was selected in his stead. The contestants appeared in the order named above and each one played three selections. For a time the hall rang with the familiar strains of Money Musk, Birdie, Soldier's Joy, Forked Deer and other old time airs. At the conclusion of the contest the judges decided a tie between Hammond and McElwain and the money was divided evenly between them. - Marlinton Messenger.Smith tells a story about a pair of later encounters between the two.15

He had, ah, some friends over there where he lived, he lived over on, ah, it was over from town, on a creek there and I can't think of the name of the creek, but anyway, where he lived the neighbourhood he lived in was mostly his friends, you know, and they'd been around him for years so he picked him out three judges so when he went to the contest they'd be in his favour, you know. Well anyhow, he went on to the contest and this, them judges all give it to Jack that time and beat Dad, so they said, and Alvin Wayne, he was Dad's main head leader, you know, he came around again later on, he said, 'Well, we're gonna have another contest, Edden,' he said, 'you a-going?' 'Well,' he said 'under one condition,' and he said 'What's that?' He said, 'If you'll have them to leave the judging up to the majority of the people I'll go,' he said. 'All right. I'll see that they do that.' Well they went and that time they left it up to the majority of the people to judge the fiddling and they give it to Dad, and Jack he never did go to no more contests ... He played around for dances over there where he lived in the neighbourhood around here and yonder but he never went to no more contests. He played a tune he called Old Sledge. Now that was a good old tune. Dad learned it off him ... He knew a lot of old-time tunes, Jack did, and he was good on them.Alice remembers another rare loss to a different fiddler which she believes is attributable to the officiating rather than the playing.

I know he went one time and he played this contest and they come to him and asked him to let them give him second, they said, you know he'd been taking the first prize all the time, he said they was gonna get all mad and not come back. So they gave him second prize ... That was when we lived in Greenbrier County or somewhere, he went to this contest.Alice believes that this explanation might well refer to her father's 1941 loss to a youthful Oscar Wright in the Greenbrier Valley Championship, an event which Edden won in both the preceding and following years.

Of all Edden's musical acquaintances the Hammonses speak most vividly of the notable Randolph Countian Wren McGee, who died in the 1930s. The undisputed champion of his region, McGee reportedly held the Elkins championship for many years running before relinquishing the crown to his nephew and understudy, Gus McGee. Smith remembers several visits to the McGee home on Riffles Creek about 1915 or so and states that his father learned 'Birdie' among other tunes from the elder fiddler. Currence Hammons, Edden's musical sidekick during his stay in Randolph County, corroborates Smith's belief in telling his eyewitness version of the first meeting between the two champions.

Currence: Mike was Wren McGee's uncle but he [Wren] come down there to play the fiddle for Mike, you know. They'd get together and play together. But Edden lived right across the hill from Mike's and Wren didn't know Edden or Edden didn't know Wren. But they wanted them to get together to hear 'em play. Well Gerald Harris lived right below my dad, he lived on Light Run. And Gerald had told Mike McGee and all of them if Edden Hammons ever got stuck with Wren McGee and went to playing that he'd beat Wren McGee so far that Wren wouldn't play anywhere he was at. Oh, Mike, it made Mike about half mad, you know, but they sent over and got Ed.Currence notes that his uncle routinely toted his instrument around in a flour sack, much to the amusement of those around him.Here come Edden, a-carrying his fiddle in a flour poke - oh be one of those twenty-five pound flour pokes, you know, and the bow would stick up about that high out of the top of the poke ... He come there, 'Come in,' it was a-sprinkling rain and Wren was a-setting there playing the fiddle, you know. Oh, Wren was a good fiddler, there's no question to it, but he's a tall slim feller. I'll bet you his fingers, was way oh, my Lord, not much longer than mine. Just little old peaked things. Well, he was a-playing, Edden came in. Well, when Edden come in, Wren kinda quit playing a-standing there. Edden said 'Now don't quit playing, I want to hear that music.' And Wren, he got in to play one, and finally they said to Wren, said, 'Ah, Mr. McGee, play that 'Birdie.' ' Edden said, ' 'Birdie'? 'Pon my honour I never heard that.' And now I never'd hear'd it. I never did hear till I hear'd Wren play it. And I was sitting there by him and I said, 'No, I never hear'd it.' ' 'Pon my honour,' Edden said, 'Play it, I want to hear that.' Well Wren, he played 'Birdie', Edden said to him, he said, 'Play 'Be All Smiles Tonight' ' and Edden could play that. He played that, he played it.

And now he said, 'Mr Hammons, I've heard a lot of talk about you. I want to hear you play one.' ''Pon my honour,' Edden said, 'I can't play. But,' he said, 'I'll try.' He went to get his fiddle, you know, and Wren said, 'Here, play on mine.' Edden looked over, 'Oh no, on my honour, I'll get mine.' He just went over and pulled her out of the flour sack. And the flour sack was wet, you know. It'd rained on it, it was really sprinkling rain when he'd come in. Pulled her out and tucked the fiddle and knocked the old flour out of it and blowed it off. Wren just stood and looked at him. Now, he never took his eyes off him. Indeed that fiddle was white of flour all over it. Took an old handkerchief out of his pocket and knocked it off of the strings and swept it off. Well, he played, 'Be All Smiles Tonight', the first one Edden played. Wren stood and listened at him. Wren never said a word. But Edden, Edden said to him, he said, 'Mr. McGee I want to hear you play that 'Birdie' again.' He said, 'I never heard that piece and my honour that's a good one.' Well Wren got his fiddle. He went to playing it, you know. Edden a-standing there and listened at him. After he played it, Edden said 'On my honour, I wonder if I can start it?' He went to fooling over the fiddle, trying to get the notes to 'Birdie', and he found them.

I'm a son-of-a-gun if he didn't show Wren McGee how to play 'Birdie'. Wren just stood and listened at him and when he got done playing it, Wren took his fiddle and put it in the case and shut it up. He would not get his fiddle out of the case anymore that night. He said, 'He's got me beat,' he said, 'I don't know how to play the fiddle.'

The violin had a weasel head on it, you know, at the end of the neck over here where the keys was - a weasel head and ah, had its tongue a-sticking out ... that's the one he carried in the flour poke. That's the one that me and him played down here at Elkins for the first prize we won first prize with. I never hear'd such hollering and laughing as people [did] in my life. Edden, oh they had them nice one hundred dollar fiddles and them they said was cheap, and they said, well, it come Edden's turn he just walked over to the corner and picked up the flour poke and they all got to looking to what he was getting. He pulled that old fiddle out and flour was all over it. He dusted it off, blowed it off, you know. Some of them went to laughing and hollering about that flour. 'Upon my honour,' Edden said, 'that's just as good as the best cases made,' he said, 'that flour makes her play good.' I never will forget that.Most of Edden's fiddle playing of course did not take place in fiddle contests and private showdowns, but was done around the house and at dances in the homes of friends and neighbours. On weekends the Hammons household became a gathering place of musicians and musical enthusiasts from all over. Yet his children remember Edden as a shy man who basically disdained crowds and insisted upon silence when he played. He viewed his popularity as a mixed blessing - more favourably in his younger days than in his older ones. Frequent unwelcome visitors to his home caused him to pick up and move on at least one occasion. A less drastic solution took the form of camping trips or visits to relatives.

Alice: I can remember growing up that on the weekends there'd be so many people come in to hear them play the fiddle, guitar, and banjo. He'd get up some weekends and he'd say, 'Betty, let's get away from the house. I don't want to play the fiddle for 'em.' He'd take us fishing and stay all day or go to, ah, some of their houses and stay all night, to get out of playing the fiddle. Manys, manys of times that would happen. He'd tell us to go somewhere, and you know that was after we was up big enough, you know, to go and he'd say, 'You girls go and stay somewhere and Betty and me's going to so and so's and I'm not playing the violin.' But they just came, so many people, that they'd just fill the house up.Emma explains that the telephone offered an often-tapped means of access to her father's music (as well as being a vital link to the local sheriff's office, from which Edden received advance warning of the presence of revenuers in the proximity).

They'd call him up and tell him to play such and such a tune that somebody wanted to hear him that were visiting and would he play it, and my father would take the receiver off and let it hang down and he'd play tune after tune for them, and all the people who owned a telephone, I suppose, would listen in ... usually in the evening when everybody was home ... As I say, it was a party line and everybody had his own ring, like ours, I believe, and I was only about four or five or something, but it seems to me ours one and a half rings, and other people's were one and others two and so on, and when you'd hear the phone ring you'd know exactly whose phone they were calling, and if it was ours, I'm sure everybody took the receiver off to listen to what was going on.Edden had several opportunities to share his talent with a wider audience. His children vaguely recall propositions by an 'east coast' record company in the 1920s or '30s, and have firm memories of attempts by Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb, and others to lure their father to Nashville in the 1940s. They agree that Edden's reluctance to leave home, coupled with a wariness of city folk, caused him to spurn such offers with little thought. Nevertheless, some relatives insist they heard Edden play over the radio on various occasions. Emma also recalls that he once appeared in a wartime newsreel playing before President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the Greenbrier resort in White Sulphur Springs. By and large, however, Edden Hammons was a local phenomenon without outside influence or impact.18

Best known for his important book John Henry: A Folklore Study, ![]() 19 which established the factual basis and West Virginia roots of the John Henry legend, Chappell was at the time conducting an ambitious field recording project to document West Virginia's fading musical traditions.

19 which established the factual basis and West Virginia roots of the John Henry legend, Chappell was at the time conducting an ambitious field recording project to document West Virginia's fading musical traditions.  Aided by a grant from the American Philosophical Society, he had purchased a handmade disc recorder in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1937 at the suggestion of friend and colleague John A Lomax. He devoted whatever time he could muster over the ensuing decade scouring the rugged West Virginia countryside in search of traditional music and musicians. By the end of 1947 he had amassed an archive of 647 recordings embracing over 2,000 folksongs and tunes.

Aided by a grant from the American Philosophical Society, he had purchased a handmade disc recorder in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1937 at the suggestion of friend and colleague John A Lomax. He devoted whatever time he could muster over the ensuing decade scouring the rugged West Virginia countryside in search of traditional music and musicians. By the end of 1947 he had amassed an archive of 647 recordings embracing over 2,000 folksongs and tunes. ![]() 20 Edden Hammons was one of the last and most skilled of the 100 or so performers he recorded. The late Patrick Gainer, a colleague of Chappell and a noted folklorist in his own right, recalls the circumstances which led to the Hammons recordings:

20 Edden Hammons was one of the last and most skilled of the 100 or so performers he recorded. The late Patrick Gainer, a colleague of Chappell and a noted folklorist in his own right, recalls the circumstances which led to the Hammons recordings:

Patrick Gainer: I taught a class in extension at Richwood and, ah, one of my students mentioned that this old time fiddler lived up, oh, some miles from Richwood, I forget exactly where Edden lived at that time, and he said he would bring him into the class and so he brought Edden with his fiddle in, and the car was parked outside the school building and Edden played a little bit and then he'd say 'I have to go get a little bit of my medicine,' and, ah, he, I would go out with him to the car and he'd get a little nip of whiskey - you never knew though, he, ah, I never saw him drunk, but oh he liked a little bit now and then, and then I brought Edden into Morgantown. He stayed all night one night with Chappell. I brought him in, and then the next day I took him to Arthurdale where they were having a folk festival and I had arranged the folk festival and, ah, part of this Arthurdale meeting, and we had there, we had Jean Thomas, and, oh, who's the editor, the famous editor of the Pocahontas Times ... Calvin Price, and Felix Robinson and several others, and I had formed them around a half circle and it was a bean-stringing and we were stringing beans and so we would sing songs and tell stories, and then I had instructed Edmund to come in at a certain time and we had just sung a hymn. Edden came to the door and he said, 'Well, I was coming down the road and I a-heard you singing hymns - I didn't know whether I was coming to a meeting or a bean stringing.'Newspaper accounts of the Arthurdale festival place the event on the 23rd of August 1947.J C: What sort of man was he?

Well, he was of even temperament as far as I know ... He was very friendly and, ah, he would tell stories and in his speech he reminded me of Tennyson's poem 'Northern Farmer Old Style.' ... He'd say, 'Well, he's a better fiddler nor me,' he'd say. That's the way he talked ... That 'better nor' is, is old middle English, you know.

In the mid-1970s Chappell donated his archives to West Virginia University's West Virginia and Regional History Collection. The donation prompted a close relationship between the folklorist and curator George Parkinson, who was eager to hear Chappell's reminiscences. While Chappell declined to be recorded, Parkinson's recollection of their conversations affords a colourful view of Chappell's encounters with the ageing Hammons.

George Parkinson: Now, the way Chappell worked was he'd set his machinery up in a local hotel and then go out and pick up the singers, folk artists, and bring them to the hotel. The first time he recorded Ed Hammons he said he took him to the hotel in Richwood. He had his recorder set up in one of the rooms facing the streets and Ed, this is how Chappell refers to him, as 'Ed', and his son James were along, both of them. Ed and James didn't bring their instruments with them. They borrowed some in town and Chappell says that during this first recording session the fiddle was a new fiddle which Ed borrowed and it didn't quite work too well, so in between recording sessions Ed would take out his pocket knife and whittle on the bridge to get it down to the right size. As Chappell tells it, Ed had a reputation because he played so well, that whenever he would play, crowds would gather. Chappell claims that there was a law of some sort passed that Ed should not play in any towns at all - evidently he was that much of a nuisance. In this particular recording session in Richwood, Chappell says the people gathered all the way up the stairs of the hotel, in the lobby of the hotel and out in the street, and he had to quit recording. But later on he went back and had a second recording session with Ed where he took Ed to a hotel, no it was a motel out in the country someplace - not only was it out in the country but one of the cabins was back off the main road where nobody could hear the playing.According to Chappell's notes the two sessions mentioned above occurred on August 14th and 15th, 1947. A third session took place on the 23rd in Chappell's Morgantown home where Hammons spent the nights surrounding the Arthurdale festival. Parkinson recalls Chappell's account of Edden's visit to Morgantown.

During the New Deal there was some sort of folk festival out at Arthurdale, which was one of Eleanor Roosevelt's pet communities, and they wanted Ed Hammons to play, Pat Gainer did, and Chappell arranged so that Ed was able to get up to Arthurdale. As Chappell tells the story, he wasn't going to get involved until he knew exactly what Ed was going to be paid, and he got from Gainer a fixed offer of thirty-five dollars. So Chappell went down and picked Ed up on a Friday and kept Ed in his house on Friday night ... Ed played the next day, which was a Saturday, at the festival. Afterwards he was paid by check, thirty-five dollars. Chappell says Ed just didn't know what a check was. It just didn't mean anything to him so Pat Gainer took the check and gave Ed thirty-five dollars in cash, which seemed like a fortune at that time and especially to Ed. And Chappell said the plan was he was going to take Ed back the following Monday, but with all that cash Ed just couldn't wait around, he had to get back on Sunday, and he was ready to take off walking, so Chappell put him up Saturday night and drove him back the next Sunday.Altogether, Chappell's recordings of Hammons embrace variants of fifty-one different tunes on twenty-five ten-inch aluminium records. These discs provide the only extant record of Edden's playing. Fortunately, the recordings are of remarkably good quality, despite technical problems which posed a constant hindrance to Chappell's collecting efforts, and despite Edden's advanced age at the time. Several tunes show the effects of a shaky bowing arm, yet the recordings exhibit drive and intensity as well as a traditional style of playing which owes very little to the influential fiddlers of the early radio and recording industries. Sherman credits Edden's son James with keeping his Dad 'straight':

You know if it hadn't a been for James, he'd a got plum off of that, that old time music ... He could just hear a piece played - no wonder he learned them - and he'd just go ahead and play it, you see ... Now I'll tell you James was a good fiddler, too, don't think he wasn't. Edden was kind of jealous of him. But there was none of them had Edden beat - I've hear'd them all over this country, everywhere - for the old time way of playing.

John A Cuthbert

Article MT070

This essay is taken from the notes accompanying The Edden Hammons Collection (West Virginia Sound Archives 001), an LP featuring 17 recordings made in 1947 by Louis Watson Chappell. Grateful thanks are extended for permission to reproduce the article.

Harvey Sampson of Nicut, West Virginia, recalls that his father and other local fiddlers shaped maturing gourds on the vine for this purpose by placing them between a pair of boards (Sound Archives, West Virginia and Regional History Collection, Collections 82 and 250).

| Top of page | Articles | Home Page | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |