Who was the Female Drummer?

Abstract

The autobiography of Mary Anne Talbot (in some publications her name is given as Mary Ann Talbot) has been the subject of speculation regarding the veracity of her account and whether it was an autobiography or written by someone else. That Talbot was a real person is not in dispute and the account she gives of her adventures as a sailor and soldier is full of factual detail regarding people, events and places, and while there is some evidence to support her claims her alleged involvement in every case cannot be corroborated. Nonetheless, it is probable that her biography was the inspiration for the broadside ballad The Female Drummer.

Ménie Muriel Dowie edited a book titled Women Adventurers (1893). This book reprinted the autobiographies of four women who served in the armed forces masquerading as men. The women concerned are Madame Velazquez, Hannah Snell, Mrs Christian Davies and Mary Anne Talbot. In her introduction to the book Dowie says of Talbot that; 'The nobleman's daughter, Mary Anne Talbot, has a touch of the mysterious about her history, and it would be very hard to measure the proportion of fact and fiction which made up her career'.![]() 1 On the other hand Suzanne J Stark, in her book Female Tars (1996) has no problem in 'measuring' between fact and fiction when she states that 'Talbot was a well known character in London in the early years of the nineteenth century, but her claim to have served in the navy and in French and American ships was fabricated.' She goes on to say that; 'The most surprising thing about the Life and Surprising Adventures of Mary Anne Talbot is that it has for so long been accepted as a historical account.

1 On the other hand Suzanne J Stark, in her book Female Tars (1996) has no problem in 'measuring' between fact and fiction when she states that 'Talbot was a well known character in London in the early years of the nineteenth century, but her claim to have served in the navy and in French and American ships was fabricated.' She goes on to say that; 'The most surprising thing about the Life and Surprising Adventures of Mary Anne Talbot is that it has for so long been accepted as a historical account.![]() 2 American historian Debbie Lee is in general agreement with Stark and states 'Although Mary Ann Talbot played an impostor, her tale of imposture may have been a hoax.

2 American historian Debbie Lee is in general agreement with Stark and states 'Although Mary Ann Talbot played an impostor, her tale of imposture may have been a hoax.![]() 3 Lee states that Stark, in her book Female Tars:

3 Lee states that Stark, in her book Female Tars:

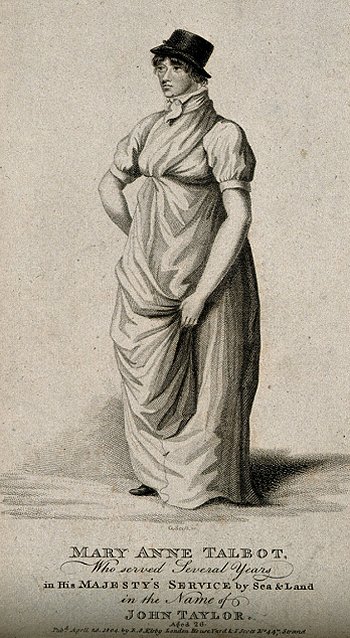

Mary Anne Talbot in her autobiography![]() 9 provides us with a colourful and remarkable account of her life but, as Stark has shown, many of her claims cannot be corroborated. She claimed that she was the youngest of sixteen 'natural' children born to the same mother and fathered by Lord William Talbot, (1710 - 1782).

9 provides us with a colourful and remarkable account of her life but, as Stark has shown, many of her claims cannot be corroborated. She claimed that she was the youngest of sixteen 'natural' children born to the same mother and fathered by Lord William Talbot, (1710 - 1782).![]() 10 Mary Anne was born in 1778 and tells us that; 'The hour which brought me into the world deprived me of the fostering care of a mother [...]

10 Mary Anne was born in 1778 and tells us that; 'The hour which brought me into the world deprived me of the fostering care of a mother [...]![]() 11 Her alleged father died when she was four and this tallies with the date of Lord Talbot's death. However, there is no record of Lord Talbot ever having a mistress that bore him sixteen children and it is more than reasonable to assume that such a long standing, productive, affair would have been very difficult to keep secret.

11 Her alleged father died when she was four and this tallies with the date of Lord Talbot's death. However, there is no record of Lord Talbot ever having a mistress that bore him sixteen children and it is more than reasonable to assume that such a long standing, productive, affair would have been very difficult to keep secret.

From the age of five to fourteen (1783 to 1792) Talbot says she attended Mrs Tapperly's Boarding School in Forgate Street, Chester. There is no record of a boarding school run by Mrs Tapperly, but there was a Mrs Tapley who ran a boarding school in Newgate Street, Chester. Derek Robson states that 'Mrs Tapley at her boarding school in Newgate Street furnished paints, silks and muslins for those pupils prepared to pay for instruction in this art' [embroidery and needlework].![]() 12 Anthony Fletcher states that her school was operational in 1775

12 Anthony Fletcher states that her school was operational in 1775![]() 13 but does not tell us how long the school existed. Newgate Street is a short distance from Forgate Street and Newgate Row is just off Forgate Street. It is possible, therefore, that Talbot did attend a boarding school in Chester and, with the lapse of time, was unable to recall the exact address and the correct spelling of the proprietors name.

13 but does not tell us how long the school existed. Newgate Street is a short distance from Forgate Street and Newgate Row is just off Forgate Street. It is possible, therefore, that Talbot did attend a boarding school in Chester and, with the lapse of time, was unable to recall the exact address and the correct spelling of the proprietors name.

Upon leaving boarding school in 1792 Talbot says that she was put in the care of a guardian, Mr Sucker in Newport. The only record of anyone by the name of Sucker at that time is of a Richard Sucker born in 1717 at Edgmond, one mile north of Newport. If Richard Sucker was her guardian he would have been seventy five years old when she was sent to him, which, on the face of it, seems an unlikely choice but nevertheless possible.![]() 14 Talbot claims that very soon after being put in his care he placed her under the care of Captain Essex Bowen of the 82nd Regiment of Foot who agreed to take her to London and arrange for her to continue her schooling. However, the 82nd Regiment of Foot was disbanded in 1784 and a regiment of that name, also known as the Prince of Wales Volunteers, was not reinstated until 1793.

14 Talbot claims that very soon after being put in his care he placed her under the care of Captain Essex Bowen of the 82nd Regiment of Foot who agreed to take her to London and arrange for her to continue her schooling. However, the 82nd Regiment of Foot was disbanded in 1784 and a regiment of that name, also known as the Prince of Wales Volunteers, was not reinstated until 1793.![]() 15 Furthermore, there is no record of a Captain Essex Bowen serving in that regiment, but there is a record of a Lieutenant Essex Bowen serving in the Royal Navy in 1758.

15 Furthermore, there is no record of a Captain Essex Bowen serving in that regiment, but there is a record of a Lieutenant Essex Bowen serving in the Royal Navy in 1758.![]() 16

16

She tells us that she arrived in London with Bowen in January 1792, in which case she would have been thirteen years old but only a month away from her fourteenth birthday. It may be that in giving the above account of leaving school and going to live with Mr Sucker she rounded up her age. Bowen, we are told, took her to the Salopian Coffee House at 42 Charing Cross which was run by a Mrs Wright. The Salopian Coffee House is listed in The Survey of London, Volume 16 where we read that; 'It is referred to in a deed of 1784 relating to the property on the site of Kirke House (immediately on the north) which is said to be bounded on the south by "A Messuage [a dwelling house with outbuildings] ... in the occupation of Mrs Wright, commonly called [...] the Salopian Coffee House".![]() 17 Ratebooks for the period show 'Ann Wright' at No. 42.

17 Ratebooks for the period show 'Ann Wright' at No. 42.![]() 18

18

Bowen reneged on his promise and instead of sending her to school he forced her to become his mistress, dress as a male and accompany him to the West Indies as his foot boy using the name of John Taylor.![]() 19 According to Talbot they travelled to Falmouth in March 1792 and boarded the Crown transport.

19 According to Talbot they travelled to Falmouth in March 1792 and boarded the Crown transport.![]() 20 Falmouth was a base for scheduled government mail routes. The Falmouth packets, or transports, were Royal Navy ships and commanded by Royal Navy officers, usually a lieutenant. Lauren Hogan writes that:

20 Falmouth was a base for scheduled government mail routes. The Falmouth packets, or transports, were Royal Navy ships and commanded by Royal Navy officers, usually a lieutenant. Lauren Hogan writes that:

There is no record of the Crown sailing from Falmouth, nonetheless Talbot tells us that they arrived in Port-au-Prince in June 1792, but their stay was cut short by the arrival of another packet ship from England which had been ordered to overtake the Crown to give new orders to join the Duke of York's troops in France. Bowen wanting Talbot to continue as his 'foot boy' and general drudge, threatened to have her sold into slavery unless she agreed to be enrolled as a drummer. She reluctantly agreed and '[...] learnt the art of beating the drum from the instructions of Drum Major Rickardson.

There is no record of the Crown sailing from Falmouth, nonetheless Talbot tells us that they arrived in Port-au-Prince in June 1792, but their stay was cut short by the arrival of another packet ship from England which had been ordered to overtake the Crown to give new orders to join the Duke of York's troops in France. Bowen wanting Talbot to continue as his 'foot boy' and general drudge, threatened to have her sold into slavery unless she agreed to be enrolled as a drummer. She reluctantly agreed and '[...] learnt the art of beating the drum from the instructions of Drum Major Rickardson.

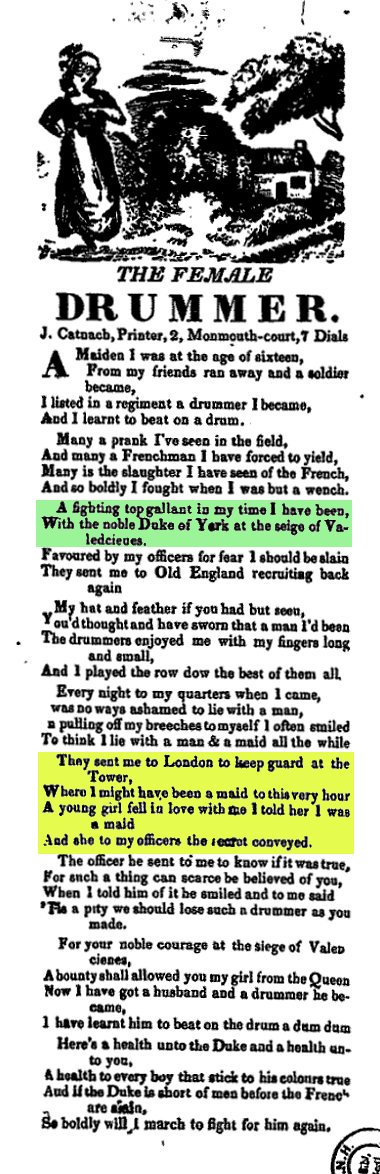

Talbot and Bowen set sail and arrived at a port in Flanders. Upon disembarkation they immediately marched off to join the main army. She was forced to continue in her duties as a drummer and during the Siege of Valenciennes![]() 24 (See graphic, right, verse 3, in green) she records that, 'I was obliged to keep up a continual roll to drown the cries and confusion of the various scenes of action.

24 (See graphic, right, verse 3, in green) she records that, 'I was obliged to keep up a continual roll to drown the cries and confusion of the various scenes of action.![]() 25

25

During the fighting she tells us that she sustained two wounds, one from a musquet [sic] ball which '... glancing between my breasts and collar bone, struck my rib: the other on the small of my back, from the broad sword of an Austrian trooper, which I imagine rather proceeded from accident than design, the marks of which two wounds I still bear. I carefully concealed them from the dread of their discovering my sex and affected a perfect cure by the assistance of a little basilicon, lint, and a few drops of Dutch drops.![]() 26 She goes on to tell us that, 'These accidents occurred the same day the Hon. Mr. Tollemache was killed by a musquet ball.

26 She goes on to tell us that, 'These accidents occurred the same day the Hon. Mr. Tollemache was killed by a musquet ball.![]() 27 Tollemache was commissioned as an Ensign in the Coldstream Guards and it was reported that he '[...] fell honourably in the trenches before Valenciennes.'

27 Tollemache was commissioned as an Ensign in the Coldstream Guards and it was reported that he '[...] fell honourably in the trenches before Valenciennes.'![]() 28 The date given for his death is 14 July 1793.

28 The date given for his death is 14 July 1793.![]() 29 Captain Bowen was also killed in the battle and this provided her with the opportunity to escape and return to England. To do so she made her way towards the coast by a circuitous route to avoid detection. Her biography relates many adventures before she arrived in England.

29 Captain Bowen was also killed in the battle and this provided her with the opportunity to escape and return to England. To do so she made her way towards the coast by a circuitous route to avoid detection. Her biography relates many adventures before she arrived in England.

She arrived in Luxemburg and in need of the means to support herself she engaged with a Captain Le Sage on the 17th September 1793 and states that; 'Soon afterwards we dropped down the Rhine, and sailed on a cruise.'![]() 30 However, she soon discovered that Le Sage captained a privateer and not, as she had thought, a merchantman. Having cruised for about four months (until January,1794) they met with the British fleet in the Channel under the command of Admiral Howe. She wrote that she refused to act against her countrymen and after a short encounter the French ship was captured. She was taken on board the Queen Charlotte to give account before Lord Howe. Le Sage confirmed that she had been unwilling to act against the British and Lord Howe put her on board The Brunswick under Captain John Harvey.

30 However, she soon discovered that Le Sage captained a privateer and not, as she had thought, a merchantman. Having cruised for about four months (until January,1794) they met with the British fleet in the Channel under the command of Admiral Howe. She wrote that she refused to act against her countrymen and after a short encounter the French ship was captured. She was taken on board the Queen Charlotte to give account before Lord Howe. Le Sage confirmed that she had been unwilling to act against the British and Lord Howe put her on board The Brunswick under Captain John Harvey.![]() 31 She records that she made a good impression on him and he appointed her as his cabin boy. She goes on to describe how The Brunswick engaged with the French ships The Vengaur and The Achilles on 1 June 1794 (the 'Glorious First of June') and describes how Harvey was wounded and later died at Portsmouth on the 30th June 1794. These encounters and events are confirmed by Edward Hawker Locker,

31 She records that she made a good impression on him and he appointed her as his cabin boy. She goes on to describe how The Brunswick engaged with the French ships The Vengaur and The Achilles on 1 June 1794 (the 'Glorious First of June') and describes how Harvey was wounded and later died at Portsmouth on the 30th June 1794. These encounters and events are confirmed by Edward Hawker Locker,![]() 32 but there is no record of Talbot ever having been on board the Brunswick. Talbot claims she was also wounded, she was hit by grapeshot in her ankle and when the ship reached port she was admitted to Haslar hospital in Gosport but due to lack of room was treated as an out-patient. She was discharged after four months of treatment (approx. end of October 1794) having, as she puts it, 'obtained a partial cure'. There is no record of John Taylor being treated at Haslar Hospital, perhaps the records for out-patients were less detailed than for those patients who were confined to the hospital.

32 but there is no record of Talbot ever having been on board the Brunswick. Talbot claims she was also wounded, she was hit by grapeshot in her ankle and when the ship reached port she was admitted to Haslar hospital in Gosport but due to lack of room was treated as an out-patient. She was discharged after four months of treatment (approx. end of October 1794) having, as she puts it, 'obtained a partial cure'. There is no record of John Taylor being treated at Haslar Hospital, perhaps the records for out-patients were less detailed than for those patients who were confined to the hospital.

She then joined a ship's company, The Vesuvius under the command of Captain Tomlinson. However, there is no record of a John Taylor serving on this ship at this time.![]() 33 The Vesuvius was in the squadron commanded by Sir Sydney Smith. According to The Naval Chronicle, 'Tomlinson ... was appointed to the Regulas, on board of which, he continued as First Lieutenant during the space of eight months. At the end of that period he left her and was soon after appointed to the command of the Pelter gun-vessel, at the recommendation of Captain, now Admiral Sir Sydney Smith.' In October, 1795 'Mr. Tomlinson was appointed First Lieutenant of The Glory, whence he removed into the V'esuve gun vessel ...'

33 The Vesuvius was in the squadron commanded by Sir Sydney Smith. According to The Naval Chronicle, 'Tomlinson ... was appointed to the Regulas, on board of which, he continued as First Lieutenant during the space of eight months. At the end of that period he left her and was soon after appointed to the command of the Pelter gun-vessel, at the recommendation of Captain, now Admiral Sir Sydney Smith.' In October, 1795 'Mr. Tomlinson was appointed First Lieutenant of The Glory, whence he removed into the V'esuve gun vessel ...'![]() 34 While serving on the Vesuvius the ship met with two French privateers and Talbot, using the name Taylor, along with a midshipman, William Richards, was taken prisoner and imprisoned at Dunkirk for 18 months. She was released in June or July 1796, (her account is not specific regarding the actual dates of these events). Following a chance encounter she engaged with Captain John Field on the American merchant ship the Ariel and set sail for New York in August. She served first as a steward then as mate.

34 While serving on the Vesuvius the ship met with two French privateers and Talbot, using the name Taylor, along with a midshipman, William Richards, was taken prisoner and imprisoned at Dunkirk for 18 months. She was released in June or July 1796, (her account is not specific regarding the actual dates of these events). Following a chance encounter she engaged with Captain John Field on the American merchant ship the Ariel and set sail for New York in August. She served first as a steward then as mate.

They arrived at New York, September 1796 and she accompanied Captain Field to his home in Providence, Rhode Island. Records confirm that a John Field was resident in Rhode Island in 1796 and had six children. The oldest was born in 1767 and would be 29 years old; the second was born in 1770 and would be 26 years old. Presumably these two eldest children were not living at home because Talbot says that at his house there were four children and his niece. The other children are listed as: Roxanne aged 18 years old; John aged 16 years old; Jerimiah aged 14 years old and Elizabeth aged 12 years old.![]() 35

35

During her stay with Captain Field and his family the captain's niece became very attached to her, taking her to be a young man. Shortly before Talbot was due to sail back to England with Field his niece proposed marriage to her. To extricate herself from this predicament she had to promise to make a speedy return from England.![]() 36 When the Ariel arrived at Rotherhithe in October 1796 Talbot revealed her true identity to Captain Field. (See verse 6 in the graphic, right, in yellow).

36 When the Ariel arrived at Rotherhithe in October 1796 Talbot revealed her true identity to Captain Field. (See verse 6 in the graphic, right, in yellow).

Talbot was now living in London and continued to have serious problems with her leg wound. She spent time in St Bartholomew's Hospital followed by a seven month stay in St George's hospital and claims to have been treated by surgeons Keate![]() 37 and Griffiths.

37 and Griffiths.![]() 38 She later spent time in Middlesex Hospital and during her stay was interviewed by a journalist and her story appeared in the Times November 4th, 1799 edition. This newspaper article was cited by John Ashton in his book Old Times and reported that:

38 She later spent time in Middlesex Hospital and during her stay was interviewed by a journalist and her story appeared in the Times November 4th, 1799 edition. This newspaper article was cited by John Ashton in his book Old Times and reported that:

According to Stark, Talbot's narrative detail simply does not match with contemporary records, yet naval historian David Cordingly takes issue with her over this. He says that part of Mary Ann's narrative might still be 'true'. She may have served under a different name, or she may have cross-dressed once or twice and served on less important military operations:

According to Stark, Talbot's narrative detail simply does not match with contemporary records, yet naval historian David Cordingly takes issue with her over this. He says that part of Mary Ann's narrative might still be 'true'. She may have served under a different name, or she may have cross-dressed once or twice and served on less important military operations:

After her discharge from hospital Talbot tells us that she spent time in Newgate prison for debt. During her time in prison she met the keeper Robert Kirby![]() 45 and told him her story. Following her release from prison she spent the last three years of her life as a domestic servant in the house of Robert Kirby who published her autobiography.

45 and told him her story. Following her release from prison she spent the last three years of her life as a domestic servant in the house of Robert Kirby who published her autobiography.

Mary Anne Talbot's account of her life cannot be fully corroborated. Nonetheless, the account of her several adventures is embellished with factual details of the actions of ships and their captains and the host of prominent historical characters she is alleged to have had contact with were around at that time. However, as we have seen, the chronology of events does not always tally. As Stark has shown, for each of the Royal Navy ships she claims to have served on there is no record of a member of the ship's company who could have been Talbot/Taylor but these records were not always reliable. Whether or not Talbot's account of her life was fabricated to gain notoriety or, as Cordingly suggests, is true in parts is a moot point. However, her leg wound does add weight to Cordingly's proposition. Alternatively if Dowie's doubts and Stark's assertion that her account is fabricated are well founded it may be that Talbot took the idea for such a story from the records of other women who served in the army or navy disguised as men. Nonetheless, it is highly likely that Talbot's account of her adventures, whether factual, a mixture of fact and fiction or entirely fabricated, provided the inspiration for the broadside writer to compose the song The Female Drummer. Her claim to have been at the Siege of Valenciennes and the specific mention of this battle in verse three of all the broadsides in the Bodlean library collection is compelling. It is interesting to note that the reference to Valenciennes does not feature in any of the versions of the song that have been collected from oral tradition that I have located.

There is nothing which links Talbot conclusively to the incidents she describes or the people she mentions in her autobiography. Nevertheless, unpacking Talbot's story to check its validity has resulted in the discovery of some tantalising pieces of information about events, places and people which correspond to her story. Although her account is fanciful and hard to believe in places, it may well, as Cordingly suggests, have some factual basis. If it does not, then it is a very well constructed 'ripping yarn'.

Arthur Knevett - 20.4.18

Article MT320

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |