Article MT256

Winston Fleary

Carriacou's Cultural Ambassador

Winston Fleary, a tall, distinguished, grey-bearded man, wearing a light purple traditional African Dashiki shirt and a colorful red, gold and green Kufi skull cap, sits on a folding chair, a drum between his legs. He looks out smiling at the group of young people standing formed in a ring before him. They have come to the Belair Heritage Park Maroon Village to listen to stories and experience the music of their island ancestors of Carriacou. No one has done more to keep alive Carriacou's rich cultural heritage than Winston Fleary.

Located in the southeast Caribbean, Carriacou is one of the tri-islands of the nation of Grenada. Carriacou's name is derived from the Amerindian word meaning 'Island of many reefs'. Amerindians were the first inhabitants of Carriacou, paddling in dugout canoes from the Oronoco River Valley in present day Venezuela to Carriacou in the fourth century. For 1300 years Amerindians inhabited Carriacou, until they were displaced by the French in the 1700s. The French brought enslaved Africans to Carriacou, transforming the heavily forested thirteen square mile island into vast fields of sugar cane and cotton. In 1763, through the Treaty of Paris, Carriacou, along with much of the French West Indies, was ceded to Britain. Besides a few years of French rule in the 1780s, Carriacou has remained a part of the British Realm ever since.

Though French and British, as well as Spanish, Amerindian and American cultures are present in the culture of Carriacou, it is best known as being the most African island in the Caribbean, and for its Big Drum Nation Dance, the most authentic African drumming, songs and dances in the Caribbean. Big Drum came to Carriacou with enslaved Africans in the mid 1700s. In the late 1700s when the British took control of much of the West Indies, an ordinance was established throughout the British West Indies which forbad slaves from playing the drum. The British feared that the drum, songs, and dances would bring a resolute pride to the enslaved; a valiant and vigilant pride which could lead to insurrection and revolt. It was not until the 1830s, near the end of slavery (1838), that Big Drum was allowed on Carriacou. Yet, it is said, during the slavery years when drumming was forbidden on Carriacou, in the silence of night, off in the unknown distance, the heartbeat of the drum echoed throughout the island.

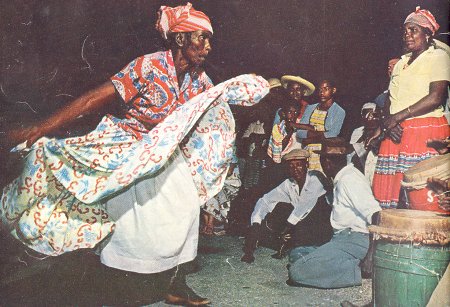

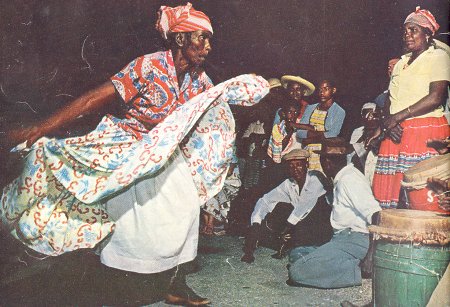

For Carriacouans, Big Drum celebrates their African identity, while at the same time commemorates their enslaved ancestors who suffered lives of bondage; the ancestors' freedom and bondage giving meaning, pride and hope to their present lives.  Big Drums are held at life gatherings such as weddings, wakes, boat launchings, house dedications, stone feasts (the laying of a deceased head stone usually two to three years after burial), and at Maroons, which are large gatherings most usually held in spring to cry out to the gods for rain. At a Big Drum spectators form a large ring. At the top of the ring are three male drummers. The lead drummer plays the cutter drum, and is accompanied by two boula drums, one on either side. The boulas drums act as bass drums, which beat out the rhythm of the song, while the lead drummer improvises and interprets the movement of the dancer. Standing beside the drummers are the singers, usually women comprising a chorus of five to twelve. Beside the singers are the dancers, the majority of them women, barefoot; dressed in traditional African head scarves and white dresses with colorful winged skirts; male dancers wear white shirts with dark slacks.

Big Drums are held at life gatherings such as weddings, wakes, boat launchings, house dedications, stone feasts (the laying of a deceased head stone usually two to three years after burial), and at Maroons, which are large gatherings most usually held in spring to cry out to the gods for rain. At a Big Drum spectators form a large ring. At the top of the ring are three male drummers. The lead drummer plays the cutter drum, and is accompanied by two boula drums, one on either side. The boulas drums act as bass drums, which beat out the rhythm of the song, while the lead drummer improvises and interprets the movement of the dancer. Standing beside the drummers are the singers, usually women comprising a chorus of five to twelve. Beside the singers are the dancers, the majority of them women, barefoot; dressed in traditional African head scarves and white dresses with colorful winged skirts; male dancers wear white shirts with dark slacks.

Big Drum begins with the ceremony of the Opening of the Ring. As the drums and voices of the chorus fill the ring and heaven with prayers and petitions, the old heads (elders) come into the ring and perform the ritual of the Wetting of the Ground. Libations of rum and water are poured in the center of the ring where the dancers will dance. The Wetting of the Ground is an invocation to the gods and ancestors, asking for their blessing and guidance, as well as an invitation to the spirits to come into the ring and join the dance.

The majority of the one hundred and twenty-nine songs and twenty-six types of dances of the Big Drum Nation Dance are from the nine different West and Central African nations of their ancestors: Cromanti, Igbo, Manding, Arada, Chamba, Kongo, Temne, Moko, and Banda. Carriacouans' national/tribal pride and heritage run so deep that the majority of Carriacouans can state their African national identity. There are three different eras of songs and dances of Big Drum Nation Dance. The Nation Songs are the oldest, and are the first dances and songs performed at a Big Drum. These songs are primarily from the three largest nations represented on Carriacou: Cromanti, Igbo and Manding. These songs and dances are invocations to the gods and spirits, asking for their blessings, as well as begging for their pardon from sin, hence the name 'Beg Pardon' songs. The songs and dances of the second era are from the days of slavery, and are sung in Creole. Creole songs are accompanied by secular dances such as the bele and hallecord, which exhibit European dance qualities such as ballroom footwork. The third type of songs is called 'Frivolous Songs'; fun-loving songs, borrowed from the neighboring islands of Grenada, Trinidad, Union Island, and Antigua.

The first dance of a Big Drum Nation Dance is always from the Cromanti nation, which was the largest group of enslaved persons sent to Carriacou, and were most likely the originators of Big Drum Nation Dance on the island (Cromanti is not the name of a nation, but is taken from Kormantin, a Dutch-built Gold Coast slave castle in present day Ghana, where enslaved people were imprisoned to await the slave ships. The Cromanti nation is made up of the tribal nations of Akan, Fanti, Ashanti and Akwapim.).

The first dance of a Big Drum Nation Dance is always from the Cromanti nation, which was the largest group of enslaved persons sent to Carriacou, and were most likely the originators of Big Drum Nation Dance on the island (Cromanti is not the name of a nation, but is taken from Kormantin, a Dutch-built Gold Coast slave castle in present day Ghana, where enslaved people were imprisoned to await the slave ships. The Cromanti nation is made up of the tribal nations of Akan, Fanti, Ashanti and Akwapim.).

It is the 'Chantwell' who initiates the song. The Chantwell, the soloist of the troop, sings the initial words of the song, which is taken up by the chorus in a call and response form. All songs are sung in their traditional national dialect. As the chorus sings, the drums enter. The two boulas drums are the first to enter into the music, laying the foundation of rhythm. The dancer, barefoot, comes into the rings, and dances before the lead drummer, who closely focuses on the dancer's feet: the beat of the lead drum converting the movement of the dancer's steps into audible rhythmic patterns. The dancers, usually females, wear traditional African head-ties, earrings, and white dresses with colorful traditional winged skirts, which the dancers hold at the ends with the tips of their fingers, the dancers arms outstretched, giving life and flight to the dances of their people.

As stated earlier, the first dances of a Big Drum are more serious, reverent dances from their African past, invoking the gods and ancestors for their blessings and begging for the pardon of sins. As the songs and dances continue into the night, Creole and Frivolous fun dances are taken up. A favorite dance of dancers and audience alike is the Bele Kawe or Hen Dance. Two women in all their beauty and fury dance against one another, their colorful winged skirts flowing and flapping, their heads bobbing and weaving,  trying to out-dance the other for the approval and affection of the cock, who joins the women in their wanton dance, strutting, prancing, dancing with each and both of the women until he chooses his hen, who he merrily dances with to the smiles and applause of everyone.

trying to out-dance the other for the approval and affection of the cock, who joins the women in their wanton dance, strutting, prancing, dancing with each and both of the women until he chooses his hen, who he merrily dances with to the smiles and applause of everyone.

Winston Fleary, sixty-seven years old, has been drummer, dancer, singer and leader of countless Big Drums throughout his life. He says the first time he consciously "came into the presence of the drum" was when he was five years old at the Big Drum held at a relative's boat launching. The lead drummer of the Big Drum was Sugar Adams, and the Chantwell, Sugar's wife, Mary Fortune, both true masters of the Big Drum Nation Dance. Carriacou's Big Drum Nation Dance was so unique that, in 1962, the world renowned American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, came to Carriacou and made field recordings of Carriacou's cultural music. Besides recording the songs of Big Drum, Lomax also recorded traditional chanteys and spirituals, as well as another musical genre unique to the island, Carriacou Quadrille.

Quadrille music and dance was introduced in the court of France around 1760. The popular dance made its way to Britain by way of British soldiers coming home from the Napoleonic wars in the early 19th century. British and French plantation owners took Quadrille with them to the West Indies. Because of the very limited number of whites on many of the plantation islands, many plantation owners used house slaves to play the fiddle and other instruments, and to fill out the dance squares of four couples per square. As the house slaves learned the stately music and dances of their 'masters', they taught Quadrille to the field slaves. In the beginning, the slaves used the European dances to mimic and poke fun at their masters; however, as time went on, especially after emancipation (Britain 1838, France 1848), the former slaves of many of the West Indies islands made Quadrille their own: each island developing its own unique style of Quadrille music and dance, a syncretic blend of European and African influences.

On Carriacou, especially in the village of L'Esterre, Quadrille became the unofficial music and dance. Carriacou Quadrille is played with a fiddle, steel (triangle) and hand held bass drum (though cuatro, guitar, banjo, tambourine and other percussion instruments may be added). Traditional Carriacou Quadrille is raw and raucous: the European derived fiddle melodies ever-flowing to the driving Afro beat of the steel (triangle) and the bass drum. The true master of the Carriacou Quadrille was fiddler Canute Caliste, who up until his death in 2005 at the age of 91 was one of the leading Quadrille fiddlers in the Lesser Islands. Caliste was also a world renowned folk artist, with some of his paintings making it to the art collections of former American president George Bush senior and Queen Elizabeth II. But it is the Quadrille Canute Caliste was most famous for: the long renowned fiddle master playing concerts in England and North America.

One such concert Canute, as well as Sugar Adams and Mary Fortune performed at was at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, in 1975. Alan Lomax and Winston Fleary, who was living in New York City at the time, were in attendance. Winston was about to enter medical school, but at the concert his vocation suddenly changed. As Winston Fleary states, "Alan was all over me, changing my perception of cultural heritage, and influencing my decisions to abandon medical school in favor of setting up a folklife program for the Big Drum Nation Dance and the music of the people of Carriacou." Throughout the 1970s, '80s, and '90s, Winston Fleary was the Director of the Folklife Institute of Grenada. He wrote the plays, Come to the Village, and The Year in the Life of Say Baba, both of which celebrate Carriacou's rich culture through song, dance, storytelling, music, and traditional crafts and food. The company performed throughout North America, Europe and the Caribbean.

Today, Winston Fleary, retired, makes his permanent home on his homeland of Carriacou. And though he lost a foot to diabetes and wears a prostheses, anytime a Big Drum is held, he is there: playing drum, leading singing (if there is no chantwell), and dancing the dances of the ancestors.  And this is the reason why the group of college students from Grenada's St George's University has traveled from the mainland of Grenada to Carriacou, to learn the stories, sing the songs and dance the dances of the ancestors. Winston Fleary looks out at the young people formed in a ring before him. He tells the students of Carriacou's most famous Big Drum dancer, Collie Landore, who danced before Queen Elizabeth II at the Queen's state visit to Grenada in 1965. The same year a photograph of Collie Landore dancing the Hen Dance at a Carriacou Big Drum was featured in National Geographic (Finisterre Sails the Windward Islands, National Geographic December 1965).

And this is the reason why the group of college students from Grenada's St George's University has traveled from the mainland of Grenada to Carriacou, to learn the stories, sing the songs and dance the dances of the ancestors. Winston Fleary looks out at the young people formed in a ring before him. He tells the students of Carriacou's most famous Big Drum dancer, Collie Landore, who danced before Queen Elizabeth II at the Queen's state visit to Grenada in 1965. The same year a photograph of Collie Landore dancing the Hen Dance at a Carriacou Big Drum was featured in National Geographic (Finisterre Sails the Windward Islands, National Geographic December 1965).

When he finishes his story, Winston Fleary rises from his seat behind the drum in order for his son Dywane, a student at St George's University, to take his seat behind the drum. As the beat of the drum fills the ring, Winston Fleary's steps come alive. He calls into the ring Donna Landore, also a student at SGU, and the great-great granddaughter of Collie Landore, to come into the ring. As Donna dances, the beat of her flowing steps dictating the beat of the drum, she reaches out and brings another young woman into the ring, and teaches her the dance. When the dance is finished, Donna touches the drum with her hand for the drumming to stop. Winston Fleary smiles approvingly at the dancers; then motions to his son to begin drumming again. He reaches out his hand to the newly initiated dancer, and leads his new protégé in a formal Quadrille Waltz; the teacher and student smiling and laughing as they dance to the heartbeat of the drum.

If you would like to learn more about Carriacou's unique cultural music, I invite you to read Rebecca Millers, Carriacou String Band Serenade: Performing Identity in the Eastern Caribbean, and Lorna McDaniel's The Big Drum Ritual of Carriacou: Praisesongs in Rememory of Flight. Alan Lomax's 1962 field recordings, Caribbean Voyage: Carriacou Calaloo, are on CD (see review), and may be obtained through Rounder Records.

Jack Russell - 16.9.10

Article MT256

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 16.9.10

Big Drums are held at life gatherings such as weddings, wakes, boat launchings, house dedications, stone feasts (the laying of a deceased head stone usually two to three years after burial), and at Maroons, which are large gatherings most usually held in spring to cry out to the gods for rain. At a Big Drum spectators form a large ring. At the top of the ring are three male drummers. The lead drummer plays the cutter drum, and is accompanied by two boula drums, one on either side. The boulas drums act as bass drums, which beat out the rhythm of the song, while the lead drummer improvises and interprets the movement of the dancer. Standing beside the drummers are the singers, usually women comprising a chorus of five to twelve. Beside the singers are the dancers, the majority of them women, barefoot; dressed in traditional African head scarves and white dresses with colorful winged skirts; male dancers wear white shirts with dark slacks.

Big Drums are held at life gatherings such as weddings, wakes, boat launchings, house dedications, stone feasts (the laying of a deceased head stone usually two to three years after burial), and at Maroons, which are large gatherings most usually held in spring to cry out to the gods for rain. At a Big Drum spectators form a large ring. At the top of the ring are three male drummers. The lead drummer plays the cutter drum, and is accompanied by two boula drums, one on either side. The boulas drums act as bass drums, which beat out the rhythm of the song, while the lead drummer improvises and interprets the movement of the dancer. Standing beside the drummers are the singers, usually women comprising a chorus of five to twelve. Beside the singers are the dancers, the majority of them women, barefoot; dressed in traditional African head scarves and white dresses with colorful winged skirts; male dancers wear white shirts with dark slacks.

The first dance of a Big Drum Nation Dance is always from the Cromanti nation, which was the largest group of enslaved persons sent to Carriacou, and were most likely the originators of Big Drum Nation Dance on the island (Cromanti is not the name of a nation, but is taken from Kormantin, a Dutch-built Gold Coast slave castle in present day Ghana, where enslaved people were imprisoned to await the slave ships. The Cromanti nation is made up of the tribal nations of Akan, Fanti, Ashanti and Akwapim.).

The first dance of a Big Drum Nation Dance is always from the Cromanti nation, which was the largest group of enslaved persons sent to Carriacou, and were most likely the originators of Big Drum Nation Dance on the island (Cromanti is not the name of a nation, but is taken from Kormantin, a Dutch-built Gold Coast slave castle in present day Ghana, where enslaved people were imprisoned to await the slave ships. The Cromanti nation is made up of the tribal nations of Akan, Fanti, Ashanti and Akwapim.).

trying to out-dance the other for the approval and affection of the cock, who joins the women in their wanton dance, strutting, prancing, dancing with each and both of the women until he chooses his hen, who he merrily dances with to the smiles and applause of everyone.

trying to out-dance the other for the approval and affection of the cock, who joins the women in their wanton dance, strutting, prancing, dancing with each and both of the women until he chooses his hen, who he merrily dances with to the smiles and applause of everyone.

And this is the reason why the group of college students from Grenada's St George's University has traveled from the mainland of Grenada to Carriacou, to learn the stories, sing the songs and dance the dances of the ancestors. Winston Fleary looks out at the young people formed in a ring before him. He tells the students of Carriacou's most famous Big Drum dancer, Collie Landore, who danced before Queen Elizabeth II at the Queen's state visit to Grenada in 1965. The same year a photograph of Collie Landore dancing the Hen Dance at a Carriacou Big Drum was featured in National Geographic (Finisterre Sails the Windward Islands, National Geographic December 1965).

And this is the reason why the group of college students from Grenada's St George's University has traveled from the mainland of Grenada to Carriacou, to learn the stories, sing the songs and dance the dances of the ancestors. Winston Fleary looks out at the young people formed in a ring before him. He tells the students of Carriacou's most famous Big Drum dancer, Collie Landore, who danced before Queen Elizabeth II at the Queen's state visit to Grenada in 1965. The same year a photograph of Collie Landore dancing the Hen Dance at a Carriacou Big Drum was featured in National Geographic (Finisterre Sails the Windward Islands, National Geographic December 1965).