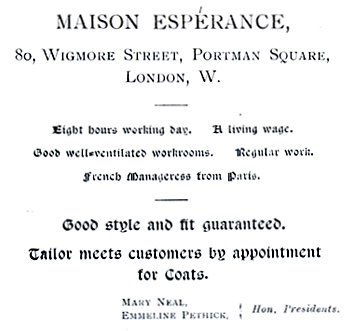

The pamphlet was dedicated to Emmeline Pethick. Maison Espérance was opened in 1897 in response to the poor working conditions and 'infringements of factory and workshop acts' that the girls reported to them.10

The advert emphasised the good working conditions, in contrast to those that the girls had described to them, which implied that the quality of the garments produced would be of a much better standard.11The settlement movement provided members of the middle-classes the opportunity to engage in some form of social work and this was also the driving force behind Mary Neal's and Emmeline Pethick's involvement with the Espérance Club. However, for Neal and Pethick there was also a political dimension to their work. This is summarised by Neal in her autobiography when she wrote:

The Morris dances and folk-songs the girls had learnt were performed at the Christmas Party and were a great success with the audience. MacIlwaine gave an account of the performance and said:

Sharp was a committee member of the FSS but was in dispute with nearly all his fellow committee members over the society's endorsement of the song list prepared by the Board of Education to be used in elementary schools.23

The song list included national as well as folk songs and Sharp was firmly of the opinion that only folk-songs should be included. Folk songs had been created and perpetuated by 'the common people', they were communal and reflected their feelings and tastes. National songs which had been composed by an individual for the people expressed the personal ideals and aspirations of the composer.Although he was in disagreement with the FSS committee Sharp gave his support to the burgeoning dance movement and seems to have been content, at this time, to let Mary Neal take the lead. The reputation of the Espérance dance team was growing and requests for team members to perform and teach others the dances were beginning to grow. The girls had learnt the dances from members of traditional morris sides that Neal had located and subsequently invited to the club to teach the girls. At the request of organisers of village fetes and celebrations they were travelling all over the country teaching the dances to groups who would then perform locally. As MacIlwaine explained; 'Neither tunes nor instructions for dancing existed anywhere in print. So far as it was possible the girls who had learned them were sent out to teach others. Since April last [1906] they have taught in several counties and in London and yet not a tenth of the demand has been met.'24

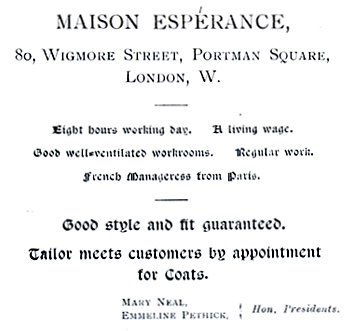

Indeed, Sharp helped in this, a request came from the Rev Francis Etherington, who was the vicar at Minehead (Somerset) and a friend of Sharp. He wanted to put on a show for a visit by the Somerset Archaeological Society and wanted to include morris dancing as a part of it. In response to this request Sharp wrote to him and told him that 'the men from Oxford (the Headington Quarry Morris Dancers) were all in full work and would find it difficult to attend.' He went on to say:It is clear that at this time Sharp was on good terms with Mary Neal. Indeed, Neal had dedicated her fund raising pamphlet, Set to Music, to Cecil Sharp.27

In the pamphlet she wrote of folk-song that; 'The songs are full of the love of the land, of the flowers and of healthy joyous life.' and contrasted them to the songs written by 'The decadent verse-writers of to-day ...'28

Featherstone wrote that both Sharp and Neal advocated a 'restorative primitivism' through the introduction of folk dance and song and that they '... argued that the decay of character, physique and traditional knowledge in English youth was due to the destructive effects of industrial and urban modernity.'29 Sharp was a romantic nationalist and, as Vic Gammon has stated, drew on ... 'a tradition of romantic thought that stretches back to the eighteenth century ...'30. He saw both folk song and folk dance as racial products, rooted in the countryside and handed down from generation to generation. In the case of song this would be through an oral/aural process and in the case of dance by practical demonstration, oral instruction and practice. Sharp's involvement with the Espérance Club provided him with the opportunity to have influence and practical involvement in the folk movement outside of the FSS.With all the increased interest in morris dancing there was a perceived need, as MacIlwaine had intimated, to provide instruction books and this need was met by Sharp and MacIlwaine. Together they located traditional morris teams and collected their dances from them. In an interview with a Morning Post correspondent Sharp said; 'You must understand that the noting of dances is far more difficult than that of music. Choreography, as the art of dance-notation is called is a much more complex science than music notation. Indeed, without Mr MacIlwaine's assistance I do not think I could have evolved the system we now use.'31

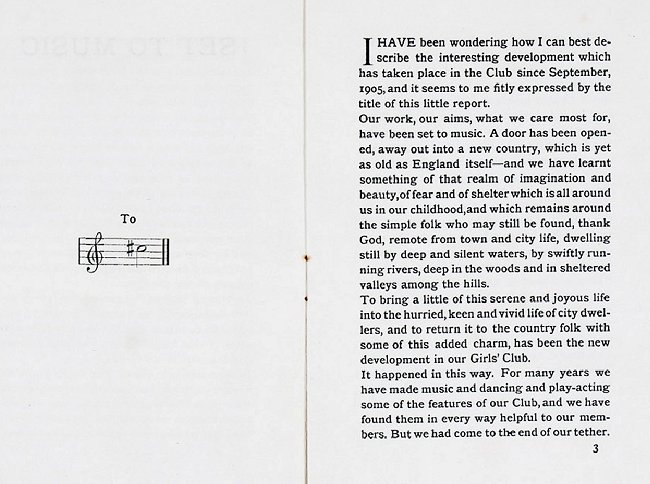

The results of their labours were published in the first four parts of The Morris Book. Part 1 appeared in 1907 and in the introduction Sharp complimented and acknowledged Mary Neal as the originator of the morris dance revival. He wrote that:On the day before the conference the event received some unexpected publicity. A cartoon and a brief, but positive, article on the revival of folk dances together with a notice of the forthcoming conference appeared in the magazine Punch. Mary Neal recorded in her autobiography that she knew nothing about it until she received a telegram from a friend congratulating her on the publicity. She wrote: 'I went out and bought a copy of Punch and was much thrilled to find the cartoon.' She went on to record that she and Herbert MacIlwaine took the copy of Punch to show it to Sharp. They were somewhat dismayed by his reaction:

Copy of cartoon 'Merrie England Once More' by Bernard Partridge that appeared in Punch on 13 November 1907, p.345 in Vol. 133. 35

What it was about the cartoon and short article that appeared in Punch that provoked Sharp to react in this way is unclear. Perhaps it was the caption 'Merrie England Once More'. Vaughan Williams had criticised his use of the term 'Merrie England' in the draft of his book Folk Song: Some Conclusions, or he may have considered that the cartoon, which depicted Mr Punch leading a group of dancers, trivialised, or even mocked, the dance movement, or perhaps it was the note under the cartoon and the article that mentioned that the movement had the excellent object of 'a return to the land' and had originated with The Espérance Club for Working Girls and went on to state that, 'We refer to the revival of Folksongs. Games and Morris Dances which under the direction of Miss Neal and Mr H C MacIlwaine, of the Espérance Club, and Mr C J Sharp, the musician has led to many charming performances at the Queen's Hall ....'36

Or it may be that Sharp thought that the article relegated his role to that of a helper, it is possible that it was all of these things. Whatever it was that caused his dismay Sharp had second thoughts and did attend the conference. When he addressed the assembly he alluded to the cartoon and the article and said that:Following Sharp's resignation Mary Neal gathered together a few of her friends and a small association was started with the idea of getting the movement outside the Espérance Girls' Club. The association grew in strength throughout the next year and Sharp grew increasingly disturbed by Neal's public portrayal of the role of the Espérance initiative. In a letter he wrote to Lucy Broadwood, the FSS Hon. Secretary, he stated:

In essence this is true but at the meeting Sharp was more restrained in expressing this view. A verbatim transcript of the meeting records that he said:

Neal commented that prior to the proposal for the establishment of the Association:

Sharp was now formulating his own ideas as to how traditional dances should be taught. In 1908 MacIlwaine resigned from his position as musical director for the Espérance Club but continued in his collaboration with Sharp in collecting and publishing morris dances. MacIlwaine's position was taken up by Clive Carey. Carey had attended Clare College, Cambridge as an organ scholar in 1901 and during his time there he combined his undergraduate studies with a Grove Scholarship in Composition at the Royal College of Music. He was a singer, a baritone, and later was to become 'singer and director of operas at the Old Vic Opera Company'.43

He was very keen on morris dancing and following his appointment as musical director for the Espérance Club he assisted Neal in collecting dances, Carey later turned his attention to song collecting.In 1910 Sharp and Herbert MacIlwaine published Part 3 of the Morris Book. Sharp was becoming concerned that Neal was, in his view, diluting the tradition through the practice of inviting traditional morris dancers to teach her girls who would learn the dances in a purely practical and visual way (one might say, a traditional way). The Morris Books were now viewed by Sharp as handbooks to be used by experts for teaching the dances. Sharp was firmly of the opinion that learning the dances solely by observation, no matter how skilled the demonstrators were, would lead to inaccuracy in performance. Moreover, if dance steps were forgotten it would be difficult to organise repeat demonstrations since the traditional dancers did not live nearby and due to work and family commitments they would not be readily available. Sharp, in his introduction to the Morris Book Part 3, insisted on the importance of using a handbook (and having a qualified teacher, where possible) to ensure accuracy and to maintain what he described as 'the traditional character' of the dance and he went on to say that; 'On this point we feel it necessary once more to offer a word of advice and warning, for we have seen again and again how easily the Morris may degenerate into a disorderly romp.44

This is in stark contrast to the compliment he paid to Mary Neal in the introduction to the Morris Book Part 1. Indeed, when a second edition of the Morris Book Part 1 was published in 1912 Sharp had removed any mention of Mary Neal and the Espérance dancers. Neal was incensed and she wrote to Clive Carey that Cecil Sharp had; '... re-written his first book with not any new mention of me and Florrie. ... my temper has its limits.45Sharp's differences with Mary Neal centred on how folk dance should be taught and performed. Sharp favoured an analytical approach in which every step is learnt exactly as recorded from the traditional dancers. Neal, on the other hand, favoured the 'intuitive method'. The vital factor in this method is demonstration by traditional performers to show the learners the rhythm, style and fluency of the movements and the resulting combined action.47

In spite of the fact that traditional dancers had learnt the dances in this way Sharp felt that 'revival' dancers who learnt from demonstration would not be able to accurately reproduce the dance steps and that this would detract from the quality of the performance. Both Neal and Sharp wanted to popularise folk dancing but for Sharp it must be taught by 'expert teachers' to ensure that the accuracy and quality of performances was in no way diluted, whereas Neal was more interested in perpetuating the spirit and joy of the dance. Georgina Boyes has stated that; 'The 'thoroughly vulgar movement' envisaged by Mary Neal formed no part of Sharp's agenda. Through the English Folk Dance Society, the Folk Revival was organised, staffed, trained and recruited among the middle classes.'48 Neither Sharp or Neal were dancers but Sharp became the self-appointed expert on morris dancing. He had no more experience than Neal but he was a musician and perhaps better able to choreograph the dances.Ironically, in the case of folk-song, it was Sharp's critics who thought that the introduction of folk-songs into the elementary school curriculum would result in performances that would be neither accurate or of good quality. Furthermore, many songs were deemed to be unsuitable and would have to be either omitted or bowdlerised and therefore a distorted view of the folk-song repertoire would be presented. National songs, however, needed no such alteration and Sharp, with the support of Ralph Vaughan Williams, were the only members of the FSS committee to object to their inclusion for use in schools. Sharp thought that folk-songs in schools was the best way to get them back into wider circulation and get them sung once more by the descendants of those that created them even if some of the school versions were not as they were originally collected and he was convinced that they would instil into the children patriotism and national pride.49

Consequently Sharp was out of step with most of his fellow FSS committee members and with Neal and her supporters in the dance movement. Nonetheless Sharp was convinced that he was right and he continued to put forward 'expert opinion' in his efforts to 'legislate' and get things done his way. By 1910 the dance movement was split between those that followed Mary Neal and the philanthropic philosophy that underpinned her organisation now known as the Espérance Guild of Morris Dancers and those that followed Sharp's ideas.Physical education in schools was not a new development, military drill had been introduced in 1871 and was a part of the secondary school curriculum, however entry to secondary school was limited and most children left school only having attended elementary school. To address the lack of physical training in elementary schools the Board of Education in consultation with the War Office issued a document entitled A model course of Physical Training for use in the Upper Departments of Public Elementary Schools. This was also based on the army methods of training and used military drill together with dumbbell and barbell exercises.51

The educational historian H C Barnard wrote that 'more sensible methods of physical education were suggested in a syllabus issued by the Board of Education in 1909. This was based largely on the practice of Sweden and Denmark ...' According to Barnard these practices had transformed the teaching of gymnastics.52 The 1909 National Syllabus stated that:Sharp was able to train, examine and grant certificates to teachers for teaching morris dancing.55

The Folk-Song Society in the 'Annual Report, June 1908-9' acknowledged Sharp's involvement in the dance movement and it was stated in the report that:

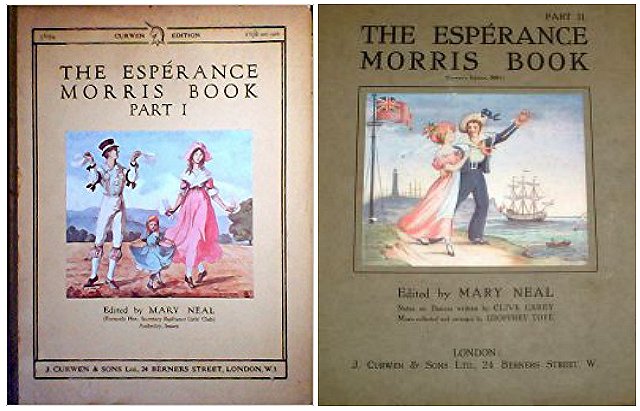

Mary Neal, The Espérance Morris Book Part I (London: Curwen, 1910).

Mary Neal, The Espérance Morris Book Part II (London: Curwen, 1911).

Neal saw them as reference manuals to be used by everyone. In this respect she was at variance with Sharp in that the books could be used by non-experts. These events brought the differences between Neal and Sharp to a head and they were aired in public. Sharp's biographer, Fox Strangways, wrote that Sharp had written to the Morning Post on 1 April 1910 to let it be known that he was disclaiming any connection with the Guild. Neal countered this by writing to Vanity Fair on 14 April 1910.59

Sharp gave an interview which was published in the Morning Post on 3 May 1910 in which he responded to the content of her letter and said that:Sharp was in broad agreement with the philanthropic motives and views of Mary Neal and the potential social effects her organisation could have, but he was in complete disagreement about the methods of teaching. He was appalled at what he now perceived as the lax standards of accuracy of the Espérance dancers. He thought that their performance and teaching would trivialise the dances and turn people away from them and thus, in due course, kill the revival. Indeed, Sharp had written to Neal telling her that she had 'deliberately isolated' herself from those who were 'better acquainted with the subject than yourself and animated by higher artistic ideals.'65

The essential difference between Sharp's approach to traditional dance and that of Neal's was that Sharp wanted precision which required expert teachers, trained under his supervision, and recognition of their achievement through certification given by him.66 Neal on the other hand was more interested in getting as many people to participate as possible and in capturing the 'spirit'. In a letter to Michael Barlow, Douglas Kennedy described Neal's approach to morris dancing as providing 'more colourful displays which we considered flamboyant'.67 In later years Kennedy admitted that Sharp may have put too much emphasis on technique and in so doing undermined the spontaneity and joy of the dance. He expressed his surprise and shock when both Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst told him that they preferred Sharp's demonstration team's performances better than those of the traditional teams.68 On reflection this is perhaps not so surprising since both men, given their musical training, would have been more attuned to the strict synchronisation of the movements rather than the more exuberant and freer style of the traditional dancers.Neither Flower nor Benson had any qualms about the relevance of folk dancing, and in particular morris dancing, to the festival since Shakespeare made reference to it in a few of his plays.79

In an article on Shakespeare and morris dancing Alan Brissenden wrote that:Sharp saw his appointment as Director of the Vacation School of Folk Song and Dance as an opportunity to bring folk dancing before a wider public and further popularise the dances which, in his view, would be for the public good. Regarding the addition of the vacation school to the festival he wrote that ' […] if the art of a country is to reflect national ideals, […] it must be deep rooted in and intimately related to the primitive art of the unlettered folk.' He went on to say 'Shakespeare is called our greatest national poet […] he was the spokesman of our race the mouthpiece, as it were, of the English folk, […] It is here that the link between the two movements, now associated with Stratford, is to be found.'88

It is clear from this that Sharp believed that greater awareness of traditional heritage would instil in people a greater sense of national identity and patriotism and thus contribute to the establishment of social cohesion. Ross Terrill in his biography of R H Tawney said, '... the problem that preoccupied social critics was the apparent loss of social cohesion.' He went on to argue that the Edwardian years 'brought mounting industrial unrest.'89 Sharp promoted folk-song and dance, particularly in education, as a means of establishing social cohesion and producing model citizens. For Sharp the way to combat such alienation and apathy among the working-classes was to introduce folk-song and dance into the elementary school curriculum. In 1910 he had written:The Society's mission was to 'disseminate a knowledge of English Folk Dances, Folk Music and Singing Games, and to encourage the practice of them in their traditional forms.' Douglas Kennedy in an article on the early years of the EFDS summarised the main activities of the Society as:

(a) The instruction of members and others in folk dancing.

(b) The training of teachers of folk dancing and the granting of certificates of proficiency.

(c) The holding of public demonstrations of folk dancing.

(d) The holding of dance meetings for members at which dancing will be general (Country Dance Parties) and at meetings at which papers will be read and discussed.

(e) The publication of literature dealing with folk dancing and kindred subjects.

(f)The foundation, organisation and artistic control of local branches in London, the Provinces and elsewhere.93

The constitution of the new Society was similar to that of the Folk-Song Society but only one third of the committee retired each year whereas it was half the committee of the FSS that retired each year. However, in both cases the retiring members could stand for re-election. Those with official roles, such as Honorary Secretary, were obliged to stand for election each year at the Annual General Meeting. On the face of it this presents a very democratic structure. Christopher Bearman considered that the EFDS compared well with the FSS in terms of 'democracy and openess [sic] of management'.94

However, all the committee members had, in the first instance, been appointed rather than elected and all were known personally to Cecil Sharp. Maud and Helen Karpeles demonstrated dances at his lectures; Ralph Vaughan Williams was a close friend and a fellow committee member of the FSS as was Alice Gomme; Sir Archibald Flower was the Chair of the Board of Governors of the Stratford Festival; Hercy Denman, was a morris dance enthusiast who had informed Sharp of traditional dances in his area of Nottinghamshire. Charlotte Sidgwick95 was a founder member of the Oxford Society for the Revival of the Folk-Dance and this was later to become a branch of the EFDS.96 Percival Lucas, a morris dance enthusiast, was the younger brother of E V (Edward Verrall) Lucas97 the noted travel writer and biographer of Charles Lamb. Percival was a genealogist and writer and he would later edit the first two numbers of the English Folk Dance Society's Journal (EFDSJ). There would be no further editions until 1927.

Front cover of the first EFDS Journal, Vol. 1 no.1, May 1914 (pp.1-32).

Vol. 1 no.2 was published April 1915 (pp.33-64).

Percival Lucas was married to Madeleine Maynell, the daughter of William Maynell the writer and critic, her mother was Alice (née Thompson) the poet and essayist.98

Madeleine's sister, Viola, was a friend of the writer D H Lawrence and in early 1915 the Lawrence's lived in her cottage. Roger Ebbatson wrote that:The remaining member of the committee was George Jerrard Wilkinson, he was a professional musician and had succeeded Sharp as music teacher at the Ludgrove preparatory school, which prepared pupils for public schools, mainly Eton. Sharp had held this position from 1893 to 1910 when, according to Fox Strangways, he was persuaded by his wife to resign his post and give his time fully to folk music. Alongside this post from 1896 to 1905 Sharp had been the Principal of the Hampstead Conservatoire, owned by Arthur Blackwood, whom Sharp had met during his time in Australia. He was also the music teacher '... to the royal children at Marlborough House'. This was a part-time appointment, the lessons were held twice a week during the summer from 1904 to 1907.104

Lucy Broadwood wrote and congratulated him on his appointment, she said; 'I was charmed with your account of your Royal folk-song singers ... I think it rests with you to raise up a musicianly king who (like Charles II) really knows what is what and encourages it!'105 The two main posts amounted to full-time work and Sharp had used the school holidays for collecting dances and songs and evenings and weekends for lectures, teaching dancing and adjudicating for exams and competitions. After 1905, Ludgrove was his only source of regular income so to give it up was something of a 'leap of faith' since he was left with only lecture fees and royalties from book sales to live on.106Dorrette Wilkie, the Head Mistress of the South Western Polytechnic in Chelsea, and George Butterworth were subsequently added to the committee membership. George Butterworth was introduced to folk-song by his friend Ralph Vaughan Williams. He had joined the FSS in 1906 and actively collected songs over the next seven years. He became a close friend of Cecil Sharp and developed a keen interest in morris dancing. He had attended the 1911 December school at Stratford as a student and Fox Strangways wrote that George Butterworth said of the experience that 'it was one of the few occasions when he felt he had lived in a really musical atmosphere.'107

The first President of the Society was Lady Mary Trefusis who accepted the appointment in 1912. Sharp had known her during his time in Australia where she was known as Lady Mary Lygon before her marriage to Colonel Trefusis. She was the 'eldest daughter of the Earl of Beauchamp, and, ... Woman of the Bedchamber to Queen Mary.'108

She was very enthusiastic about dance and worked tirelessly in her home county of Cornwall to bring folk dancing to as wide a public as possible. It is interesting to note that both the FSS and the EFDS attracted as members people who believed that in some way the promotion of folk-song and dance would enhance and make more tolerable the daily lives of working people. The promotion of social reform did not seem to be considered.The original side of six morris dancers gave its first public performance on 27 February 1912 at the inaugural 'At Home' event organised by the newly formed EFDS. From that time on they were frequently, often with the addition of R J E Tiddy, called upon by Sharp to provide practical demonstrations at his lectures. However, in December 1912 they made their first appearance on a London stage at the Savoy Theatre. The venue had been 'lent for a matinee performance by the actors Miss Lillah McCarthy and Mr Granville Barker'. Lillah McCarthy was married to Harley Granville Barker and they jointly managed the Savoy Theatre at that time. Granville Barker was presenting a series of Shakespeare's plays during 1912 at the Savoy. It may be that Sharp's association with the Stratford festival prompted Granville Barker and his wife to offer the use of the Savoy for a display of morris dancing. Presenting morris dancing at the theatre alongside Shakespeare's plays served to further reinforce the connection between the two.

Claude Wright and James Paterson were trained as physical education teachers and as such brought to the morris team a more energetic performance than the other four. In due course, as the team became established this difference in approach started to cause a rift in the ranks. James C Brickwedde quotes from an interview he had with Douglas Kennedy about the team and these differences, Kennedy told him that, 'We [Sharp, Kennedy, Butterworth, Wilkinson, et al.] were really more musicians than physical people ... Paterson and Wright ... stood out like sore teeth [sic] in our eyes because they were doing things from a physical point of view.'113

Nonetheless, in the early years Wright was a key dancer for Sharp and was often called upon to demonstrate solo morris jigs. At the 1912 Stratford-Upon-Avon festival Sharp had appointed him as one of the instructors.The invitation to Wright and his subsequent acceptance resulted in a definite cooling of Sharp's relationship with Wright. In Sharp's view protocol had been breached since the invitation had been sent straight to Wright and not through Sharp who felt that, as Director of the dance school at the festival, any invitation to one of his instructors should be through him. Wright accepted the invitation and went to America as a 'free agent' and not as a representative of Sharp's dance school. However, upon his return he found that his place in the demonstration team had been filled and from then on he was effectively 'sidelined' from Society activities.

The invitation to Claude Wright to go to America to teach dance had resulted from the enthusiasm for morris dancing that had been engendered by Mary Neal and Florence Warren during their visit to America. Neal's account of the visit highlights the growing antipathy between her and Sharp. Neal had been approached by an American lady who had attended the concert that Neal and her dancers had given at Lord Ellesmere's Bridgewater House and she and Florence Warren were invited to go to America to lecture on and teach the dances. Neal agreed to go and she recorded that:

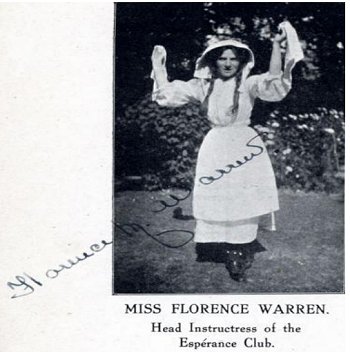

Signed Photograph of Miss Florence Warren, from the Espérance Club Book Part 1 118

The conclusion to be drawn from Sharp's attempt to sabotage Neal's American trip is that he wanted complete control of the dance movement and saw Neal as a threat to that. In the case of Claude Wright it appears that he regarded his behaviour as insubordinate to his authority and did everything in his power to undermine his activities in America. While Sharp maintained control of the EFDS affairs and members 'towed his line' then he was generous and magnanimous in his dealings with them but, as far as Sharp was concerned, Wright had crossed the rubicon. Furthermore, Kennedy's account of the treatment Wright received from other members of the team suggests that Sharp's animosity towards Wright was taken up by them.

Brickwedde quotes from a letter Wright wrote to Baker after his trip to America in which he said 'I talked to Sharp of the trip and it was curious the way he took it. Since then the old jealous attitude of the Wilkinsonites is very marked and I almost wonder if Sharp is very happy that I have been so successful.'119

In addition to this, in Fox Strangeways and Karpeles biography of Sharp both Wright and Peterson are only mentioned by name, no detail about them is provided as it is for the other members of the dance team and there is no mention of Wright's activities in America. This is hardly surprising, Fox Strangways and Karpeles were both close friends of Sharp, greatly admired his work and accepted him as the leader of the folk-song and dance movement.Sharp continued his involvement with the Stratford Festival and the Stratford-Upon-Avon Herald reported on the 1913 festival. The dance school attracted 'nearly 450 students'.120

The report stated that:

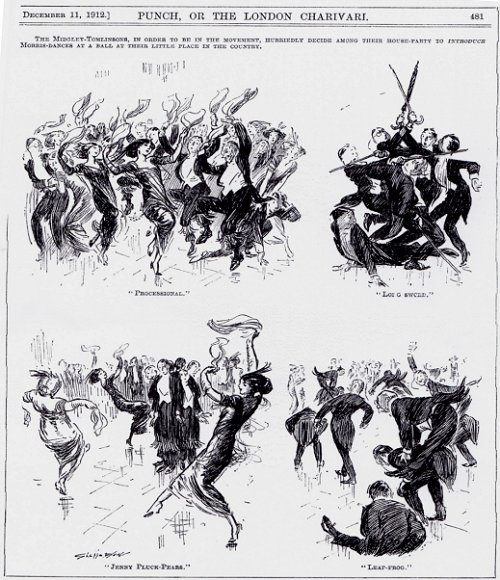

Copy of cartoon by Claude Allin Shepperson that appeared in Punch magazine December 11 1912, p. 481, Vol 143.

The heading reads 'The Midgley-Tomlinsons, in order to be in the movement, hurriedly decide among their house-party

to introduce Morris dances at a ball at their little place in the country.' The captions for each illustration read

(from top left and working clockwise) "Processional", "Long Sword", "Leap Frog" and "Jenny Pluck-Pears".122

Sharp's energy and commitment to all things folk was un-bounding. This was in spite of his continual health problems, he was a chronic asthmatic and suffered from severe arthritis which affected his eyes (iritis) and gave him periodic acute headaches and temporary loss of sight. As well as building up the English Folk Dance Society and collecting new dances he still found time to add another three hundred and fifty songs to his collection in the three year period 1912 to 1914.123

Sharp's tactics were so effective that Mary Neal's contribution to the dance movement was for many years ignored or unknown to many people. Margaret Dean-Smith clearly believed that information about her involvement had been deliberately excluded from the history of the movement. In a letter to Clive Carey she wrote:

Arthur Knevett - 10.5.19

Notes:

1

Jose Harris, 'Social Evils and Social Problems in Britain, 1904-2008' (June, 2009), available at http://jrf.org.uk/social-evils [Accessed 19 February 2018]

Article MT322

2

Simon Featherstone, Englishness: Twentieth Century Popular Culture and the Forming of English Identity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009) p.28.

3

Mary Neal, As a Tale That is Told, pp.14-15 unpublished autobiography available at http://www.maryneal.org/object/6386/ [accessed 27 February 2018].

4

Ellen Ross, "Disgruntled Missionaries": The Friendship of Mary Neal and Emmeline Pethick Lawrence at the West London Mission. Available at http://www.maryneal.org/file-uploads/files/file/MNPellen-ross-essay.pdf [accessed 3 May 2018].

5

Mary Neal, As a Tale That is Told p.48. The Bitter Cry of Outcast London: An Inquiry Into the Conditions of the Abject Poor was written by Andrew Mearns and publishes as a penny pamphlet in 1883.

6

Roy Judge, 'Mary Neal and the Espérance Morris' Folk Music Journal, 5.3 (1989), 545-592. (p. 547).

7

Espérance meaning hope, a word used several times by Shakespeare, see for example King Henry the Fourth Part 1, Act 5, scene 2. Hotspur addressing Percy.

8

Mary Neal, As a Tale That is Told p.88 .

9

Mary Neal, Dear Mother Earth (London: Headley Brothers, Printers, nd. [1901])

10

Mary Neal, As a Tale That is Told p.88 .

11

Mary Neal, Dear Mother Earth, one of the adverts printed on the back cover of the pamphlet.

12

Mary Neal, My Pretty Maid: The Story of a Girls Club (London: Headley Brothers, nd [1905]), p.4.

13

Mary Neal, My Pretty Maid . p.6.

14

Mary Neal, Hon.Sec. Espérance Working Girls' Club, Set To Music (London: Keigate Press for the Espérance Club, nd [1907]), p.3.

15

Roy Dommett, 'How do you think it was?', available at http://www.maryneal.org/artist/6284/ [accessed 28 February 2018].

16

Mary Neal, As a Tale That is Told p. 88.

17

London, Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML), Cecil J. Sharp MSS, Correspondence, Biographical information on Herbert MacIlwaine sent to A. H. Fox Strangways for his biography of Cecil Sharp. Hand-written note, writer not identified. CJS1/12/13/2/6.

18

Mary Neal, Set To Music (London: Reigate Press for Espérance Club, nd [1905]), p.4. See also, Roy Judge, 'Mary Neal and the Espérance Morris', p.549

19

Mary Neal, Set To Music, p.4.

20

Mary Neal, Set To Music, p.6. Also, for an account of Sharp's meeting with the Headington Morris Team see A.H. Fox Strangways in collaboration with Maud Karpeles Cecil Sharp (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933), pp.26-27.

21

H C MacIlwaine, 'The Revival of Morris Dancing' Musical Times, 47.766 (1 December 1906), 802 -805, (p.804).

22

Mary Neal, Set To Music, p.6. See also, Roy Judge, 'Mary Neal and the Espérance Morris',

p. 550.

23

See Arthur Knevett, 'Folk Songs for Schools: Cecil Sharp , Patriotism and The National Song Book', Folk Music Journal, 13.3 (2018), 47-71.

24

H C MacIlwaine, 'The Revival of Morris Dancing', p.805.

25

London, VWML Cecil J Sharp MSS, Correspondence Letter from Cecil Sharp to Rev Francis Etherington, dated 25 May 1906. CJS1/12/5/2/3.

26

Roy Judge, 'Mary Neal and the Espérance Morris', p.550.

27

Mary Neal, Set To Music, p2.

28

Mary Neal, Set To Music, p.5.

29

Simon Featherstone, Englishness, p.28.

30

Vic Gammon, 'Cecil Sharp and English Folk Music' in Still Growing compiled and edited by Steve Roud, Eddie Upton and Malcolm Taylor (London: English Folk Dance and Song Society in association with Folk South West, 2003), pp.2-22 (p.11).

31

London, VWML, Clive Carey MSS Collection.. 'The Revival of English Folk-Dance, Mr Sharp's Views (From a Correspondent)'. Press cutting from The Morning Post, 3 May 1910. CC/3/3.

32

Cecil J Sharp and Herbert C Macilwaine The Morris Book : with a Description of Eleven Dances as Performed by the Morris-Men of England The Morris Book Part I (London: Novello,1907) p.4.

33

Roy Judge, 'Mary Neal and the Espérance Morris', p.551.

34

Mary Neal, As a Tale That is Told p. 88.

35

Cartoon 'Merrie England Once More' from Punch magazine 13 November 1907, p.345 in Vol.133 .

36

'Come Lasses and Lads', Punch, 13 November 1907, p.347.

37

English Folk-Music in Dance and Song' transcript of the Conference held at the Goupil Gallery 5 Regent Street, Thursday 14 November 1907, at 8.30pm. available on-line at http://www.maryneal.org/object/6193/chapter/1004/ [accessed 27 February 2018]

38

Morning Post 15 November 1907.

39

Mary Neal As a Tale That is Told, p.159.

40

London, (VWML), Cecil J Sharp MSS, Correspondence Letter from Cecil Sharp to Lucy Broadwood dated 10 November 1908, Sharp Correspondence Box 5 Folder F.

41

'English Folk-Music in Dance and Song' transcript of the Conference held at the Goupil Gallery 5 Regent Street, Thursday 14 November 1907, at 8.30pm, sheet 4. Available at maryneal.org/file-uploads/files/file/1907s1b.pdf [accessed 27 February 2018].

42

Mary Neal As a Tale That is Told, p.159.

43

Carey, Francis Clive Savill (1883-1968) available at

janus.lib.cam.ac.uk>janus>Repositories>Kings>PP [accessed 2/10/2017]

44

Cecil J Sharp and Herbert C MacIlwaine, The Morris Book Part 3: with a Description of Dances as Performed by the Morris-Men of England (London: Novello, 1910), p.8.

45

VWML, Clive Carey Manuscript Collection, Postcard from Mary Neal to Clive Carey, n.d [Sept, 1912?] CC/2/2/40.

46

Zygmunt Bauman, Legislators and Interpreters: On Modernity, Post-Modernity and Intellectuals (Cambridge, Polity Press,1987.), p.4.

47

Douglas Kennedy, 'The Educational Element in Folk Music and Dance' Journal of the International Folk Music Council, 5 (1953), 48-50 (p. 49).

48

Georgina Boyes, The Imagined Village: Culture, Ideology and the English Folk Revival (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993), p.107.

49

For a full account of the controversy see; Arthur Knevett, 'Folk Songs for Schools: Cecil Sharp, Patriotism and The National Song Book' , Folk Music Journal, 11,3 (2018), 47-71.

50

Alfred Perceval Graves, To Return to All That: An Autobiography (London: Jonathan Cape, 1930), p.289.

51

Peter C McIntosh, Physical Education in England since 1800 (London: G. Bell, 1952), p.139.

52

H C Barnard, A History of English Education from 1760 2nd edition (London: London University Press,1961) ,p.226.

53

Board of Education, 'Prefatory Memorandum', The Syllabus of Physical Education for Public Elementary Schools (London: HMSO, 1909).

54

Anne Bloomfield 'The Quickening of the National Spirit: Cecil Sharp and the Pioneers of the Folk-Dance Revival in English State Schools (1900-26)', History of Education, 30, 1 (2001), 59-75 (p.69).

55

Fox Strangways and Maud Karpeles, Cecil Sharp, p.78.

56

'Annual Report June 1908-9', Journal of the Folk-Song Society, 4, 1 (1910), pp.iii - vi (p.iv).

57

'Physical Education' in Board of Education: Annual Report for 1912 of the Chief Medical Officer (London: HMSO,1912)

58

Frank Kidson and Mary Neal, English Folk-Song and Dance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1915), p.160.

59

Fox Strangways and Karpeles, pp.81-82.

60

London, VWML, Clive Carey Manuscript Collection, 'The Revival of English Folk-Dance, Mr Cecil Sharp's Views (From a Correspondent)', Morning Post 3 May 1910. CC/3/3

61

VWML, Cecil Sharp Manuscript Collection, Letter from Cecil Sharp to Percy Grainger dated 23 May 1908, CJS1/12/7/7/2.

62

Vic Gammon, ''Many Useful Lessons': Cecil Sharp and the Folk Dance Revival, 1899-1924' Cultural and Social History, 5.1 (2008) 75-98 (p.91). p.91

63

Douglas Kennedy, 'The Educational Element in Folk Music and Dance', p.49. Douglas Kennedy was a member of Sharp's demonstration Morris Team and succeeded Sharp as Director of the EFDS

64

Douglas Kennedy, 'Folk Dance Revival' Folk Music Journal, 2, 2 (1971), 80-90 (p.84).

65

London, Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, Cecil J Sharp MSS, Correspondence Letter from Cecil Sharp to Mary Neal, dated 26 July 1909, CJS/13/2/6.

66

For a list of 'Positive and Negative terms' used by Sharp when observing dancing by student teachers see Vic Gammon , 'Many Useful Lessons' p.89. The list of negative terms greatly exceeds the list of positive terms used.

67

Letter from Douglas Kennedy to Michael Barlow, cited in Michael Barlow, Whom the Gods Love, p.75

68

Douglas Kennedy, 'Folk Dance Revival', p.86.

69

Mary Neal, 'Folk Art: The Stratford-upon-Avon Festival Movement and its Developments' in Reginald R Buckley, The Shakespeare Revival and the Stratford-Upon-Avon Movement (London: George Allen & Son, 1911), pp.191-213. (pp.203-204).

70

Mary Neal, 'English Folk-Dance' in English Folk-Song and Dance, Frank Kidson and Mary Neal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1915), p.166.

71

Mary Neal 'Folk Art' pp.204-205

72

Mary Neal, The Espérance Morris Book Part 1: A Manual of Morris Dances, Folk-Songs and Singing Games 3rd edition, (London: J Curwen & Sons, nd. [1911]), p .2.

73

W R Powell (editor), 'West Ham Philanthropic Institutions' in A History of the County of Essex Volume 6 (1973) pp.141-144, available on-line at http://www.britishhistory.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42763 [accessed 08 January 2018]

74

Martha Vicinus, Independent Women: Work and Community for Single Women, 1850 - 1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), p.235.

75

Margaret Dean-Smith (1899-1997), Librarian at Cecil Sharp House, 1945-1950, Member of the JEFDSS Editorial Board, 1947-1951.

76

Margaret Dean-Smith, 'Dr Maud Karpeles, O.B.E.: 12 November 1885 - 1 October 1976' Folklore, 88,1 (1977), 110-111 (p. 110).

77

David Atkinson, 'Resources in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library: The Maud Karpeles Manuscript Collection' Folk Music Journal, 8, 1 (2001), 90-101 (p. 90).

78

David Atkinson, 'Resources in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library: The Maud Karpeles Manuscript Collection', p.198.

79

Morris dancing is mentioned in three of Shakespeare's plays: All's Well that Ends Well (Act II, scene II), Henry V (Act II, scene IV), Henry VI (Act III, scene I).

80

Alan Brissenden, 'Shakespeare and the Morris', The Review of English Studies. n..s, 20, 117 (1979), 1-11 (p. 1).

81

London, VWML, Clive Carey Manuscript Collection, 'English Folk-Dances', letter sent by Cecil Sharp to the Morning Post dated 25May, 1910, CC/3/4/1.

82

London, VWML, Cecil J Sharp MSS, Correspondence, Letter from Frank Benson to William [probably Hutchings] dated 11 November 1910, Sharp correspondence Box 6, folder C.

83

Mary Neal, 'English Folk-Dance' in English Folk-Song and Dance, p.167.

84

Paul Oppé was an art scholar and collector. In 1905 he worked for the Board of Education and specialised in teacher training standards. It is probable that Sharp met Oppé at that time through his dealings with the Board and the two became firm friends. However, at the time of writing Oppé was the Deputy Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum. He returned to the Board of Education in 1913. Paul Oppé's wife, Lyonnetta, shared both her husband's and Sharp's interest in folk dance and she later joined the EFDS in 1912.

85

London, VWML, Cecil J Sharp Manuscript Collection Letter from Cecil Sharp to Paul Oppé dated 3 May 1911. CJS1/12/15/2/1.

86

Mary Neal, 'English Folk-Dance' in English Folk-Song and Dance, pp.166-167.

87

Letter from Mary Neal to A. H. Fox Strangways dated 31 December 1933 available on-line at http://www.maryneal.org/object/6169/character/6030/ [accessed 28 February 2018]

88

Cecil J Sharp, 'The Stratford-Upon-Avon Vacation School of Folk Song and Dance' in A Handbook to the Stratford-Upon-Avon Festival, with Articles by F R Benson, Arthur Hutchunson, Reginald R Buckley, Cecil J Sharp. And Shakespeare Memorial Council (London: G Allen, 1913), pp.31 - 32.

89

Ross Terill, R H Tawney and His times: Socialism as Fellowship (London: André Deutsch, 1974) pp.200 - 201.

90

C J Sharp, cited in Anne Bloomfield 'The Quickening of the National Spirit', p.12.

91

Anne Bloomfield 'The Quickening of the National Spirit', p.90. and Derek Schofield, ''Revival of the Folk Dance: An Artistic Movement': The Foundation of the English Folk Dance Society in 1911' Folk Music Journal, 5, 2(1986), 215-219 (p.217).

92

Fox Strangways and Karpeles, p.88.

93

Douglas Kennedy, 'The Folk Dance Revival in England', Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, 2 (1935), 72-79. (p.74)

94

Christopher James Bearman, 'The English Folk Music Movement 1898-1914' (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Hull, 2001), p.98.

95

Charlotte Sidgewick was also an active member of the Association for Promoting the Higher Education of Women (AEW) and a supporter of the suffragette movement. She was supported in both these movements by her husband Arthur Sidgwick who was a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Janet Howarth surmises that his support for the AEW, and particularly his 'activities as Chairman of the Oxford City Liberal Association (1886-1910) may have cost him the presidency of Corpus in 1904.' in. 'The Self Governing University 1882-1914' in Volume VII The History of The University of Oxford: The Nineteenth Century Part II ed. by M G Brock and M C Curthoys (Oxford University Press, 2000), pp.599-644 (p.624).

96

Roy Judge, 'A Branch of May' Folk Music Journal, 2, 2 (1971), 91-95 (p.91).

97

It is interesting to note that E V Lucas wrote a review article for The Country Gentleman of a performance given by The Espérance Girls Club and this provided the Introduction to The Espérance Morris Book Part I.

98

'Lucas Family', http://www.manfamily.org/Lucas_Family.htm [accessed 14/11/2017]

99

Roger Ebbatson, ''England, My England': Lawrence, War and Nation', Literature and History, 9, 1 (2000), 67-81 (p.68).

100

Roger Ebbatson, ''England, My England' p.68.

101

Roger Ebbatson, ''England, My England' p.68.

102

D H Lawrence, 'England, My England' pp.286-313, in The Collected Short Stories of D H Lawrence (London: Wm. Heinemann, reprinted by arrangement by Book Club Associates, 1974) p.288.

103

Roger Ebbatson, ''England, My England' , p.71.

104

Fox Strangways and Karpeles, p.52.

105

London, VWML, Cecil J Sharp Manuscript Collection Letter from Lucy Broadwood to Cecil Sharp dated 16 July 1904, CJS1/13//1/13/4.

106

Fox Strangways and Karpeles, p.80.

107

Fox Strangways and Karpeles, p.87. See also Michael Barlow, Whom the Gods Love, p.77

108

Fox Strangways and Karpeles, pp.115-116.

109

English Folk Dance Society Annual Report, presented 21 May 1914.

110

'Members', Journal of the Folk-Song Society,5.1 (No.18, 1914), 97-102.

111

James C. Brickwedde, 'A Claude Wright: Cecil Sharp's Forgotten Dancer', Folk Music Journal, 6, 1 (1990), 5-36 (p.14).

112

Michael Barlow, Whom the Gods Love, p.75.

113

James C Brickwedde, p.11.

114

James C Brickwedde, p.16.

115

Mary Neal, As a Tale That is Told pp.160-161, [accessed 28 February 2018]

116

London, VWL, Letter from Mary Neal to Clive Carey dated 30 December 1910, Clive Carey Manuscript Collection, CC/2/207. I am grateful to Laura Smyth (VWML, Library & Archive Director) for deciphering the underlined part of the sentence.

117

'Americans Learning English Folk Music' An interview in "The Musical Herald", reprinted in The Esperance Morris Book Part 2: Morris Dances, Country Dances, Sword Dances and Sea Shanties ed. by Mary Neal, Notes and Steps by Clive Carey, Music Collected and Arranged by Geoffrey Toye and Clive Carey (London: J Curwen & Son, 1912), p.49

118

Signed photograph of Florence Warren available at www.maryneal.org/object/6209/chapter/1004/ [accessed 27/07/2018]

119

James C Brickwedde, p.23.

120

English Folk Song and Dance. Growth of the Movement.' Stratford-upon-Avon Herald, September 5 1913, p.2.

121

Ibid. p.6.

122

Cartoon 'The Midgley-Tomlinsons, in order to be in the movement, hurriedly decide among their house-party to introduce Morris dances at a ball at their little place in the country.' from Punch magazine December 11 1912, p.481 in Vol.143.

123

Fox Strangways and Karpeles, p.116.

124

London, VWML, Letter from Margaret Dean-Smith to Clive Carey dated 12 September 1962, Clive Carey Manuscript Collection, CC/2/4

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |