Article MT049 - from Musical Traditions No 11, Late 1993

Interviewed ...

Sad to report, Gordon Hall died on 24th January, 2000. An Obituary by Vic Smith is now also on this site - but this interview is re-published as a tribute to one of England's finest.

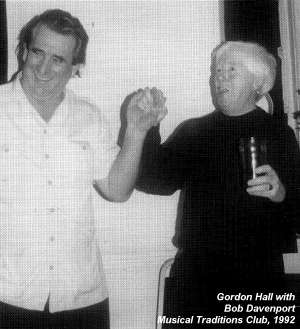

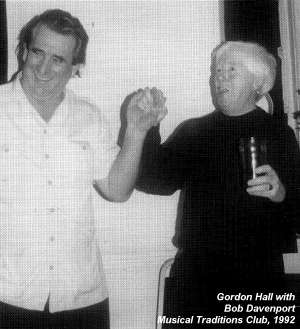

In March 1991, Gordon Hall came into the BBC Radio Sussex studios in Brighton to talk to Vic Smith and to record some songs for the programme, 'Minstrels Gallery'. He started on some fascinating stories as soon as he arrived at the studios, before the tape recorders were set in motion.  The conversation got round to what his songs mean to himself and his family, so, after a brief welcome and an introduction, that seemed to be a good point to start the interview ...

The conversation got round to what his songs mean to himself and his family, so, after a brief welcome and an introduction, that seemed to be a good point to start the interview ...

V S: I'm very pleased to be able to welcome as our studio guest on Minstrels Gallery today, Gordon Hall, who has one of the finest Sussex singing voices that you are ever likely to hear. I believe that you are one of our regular listeners?

G H: I am indeed, and not only do I listen to your lovely programme, but my eldest brother - who now lives in Normandy - he also listens to it.

We have asked you into the studio today to give us some background and an insight into yourself and your wonderful singing and the tremendous number of songs that you and your family sing. I'm going to throw you in at the deep end and ask you if can say what the songs that you have in your family mean to you.

Oh Gawd!

It seems difficult to a generation of people like me and other people growing up without songs in their family to get to know how much the songs mean to you.

It's a very difficult question to answer. All I could say is ... Well, I think the answer would be to ask you a question: what does your eyesight mean to you?

Well, everything.

Well, there you are!

It's the same with your songs?

It's the emotional involvement. With some of the songs, it's so intense that I wouldn't dream of singing them in public. In fact, the family understand if you break down, if you like, and you are sitting there singing with tears rolling down your cheeks, but I feel that it is an embarrassment for people outside the family. So certain songs, regardless of how much you love them, you wouldn't sing them outside the family context, where they understand it.

So the way that you've come to sing the songs in the way that you have been doing in folk clubs and festivals in the last few years, you must find it very different from singing them at home?

Well, as far as I'm concerned, the songs are the same for me, obviously. I'm not too sure about people in an audience outside of the family, how they would react to them. I really don't know. In fact, I remember at the National Folk Festival, I was singing Lord Beckett and I think I got to about the twentieth verse and I opened my eyes because there was absolute stillness, complete hush, and I was so surprised to find the audience still there that I promptly forgot the last two or three verses. That's absolutely true! I couldn't believe that there would be that many people, a whole roomful, that would be that interested to stay there. And, of course, there was a complete hush, which I've found most audiences are kind enough to give you when you are singing is quite foreign to me. At home nobody bothers to ... well, they are not listening for your every word. People are carrying on with their conversations, the meal's being served, the drinks are being passed around and our people would think it was quite pretentious to expect anybody to listen, in the senseŠ that nothing else was allowed to go on. you might have somebody dancing up in that corner, well, if it was a lively sort of song. Certainly no-one would bother to hush their conversation. They'd just carry on living, if you like. So it does come as something of a surprise, a very welcome surprise in a sense, but it takes a bit of adjusting to. You are not used to it.

Does it make you a bit protective about your songs? The fact that people are hanging on your every word.

What do you mean? The sense of ownership? I don't feel I own the songs. I feel they belong to all of us.

No, I was wondering, do you ever feel that you do not want to sing them because you feel they might not be well received?

To be absolutely honest, once I've shut my eyes, I'm not really interested if there is an audience there. I would enjoy it as much if I was singing at home or walking around the garden, or whatever. What I do find particularly rewarding, and it has happened to me on a few occasions, because as I tried to explain earlier, I don't really have much experience singing outside the family, is when an old - and it generally is an elderly person - comes up to you after you have sung a particular song. Say, for instance, if you sang Sam Hall and you raise the query in the song, by saying (sings):

Oh I killed a man they said, so they said, (spoken) so they said ...

And then to have an old chap come up at the end of the night and say 'You don't think he did that, do you?' Now, that is rewarding, because it means that they have followed the song, or the story. They are not necessarily interested in the way I sing it. They are interested in the story.

And the message of the song?

Well, exactly. And on one memorable occasion I was with Mr and Mrs Penfold - Mrs Alice Penfold has been recorded, I think, by Mike Yates - and we were talking about the old songs, Her husband, Eddie, said that he had, in his time, sung Lord Bateman and did I know it? Well, I said Lord Bateman to us was Lord Beckett and I started to sing the song. This was in the context of a business. we were looking after a business for someone who was ill and they were visitors. The set-up in this business was that people just wandered through the room where I'd sat down to sing and Eddie and his wife Alice were interested in the song. That virtually drove the customers away! Now I found that very rewarding. They follow every word. And I had one occasion, with Lord Randolph or Lord Rendell, or whatever you call it, you know, where she 'hangs from yonder's tree', and an old man came up to me and and said, 'Well, good enough for her!' Now, that was a man that had followed the song. He knew what it was all about.

Well, could we hear that song now?

Sings Lord Randolph ............

A tour de force! Can you remember learning that song consciously or was it something that came ...

You don't learn them, old son, when you've been brought up like I have - you absorb them. I'm still learning from my brother. If I live to be, whatever, a hundred and fifty, and Mum lives to be three hundred, I will never know every song my mother knows and has sung.  It's incredible. I've got to explain to you ... Mother is not the best scholar in the world. If you put a written version of a song she'd sang all her life in front of her, it doesn't mean anything to her at all.

It's incredible. I've got to explain to you ... Mother is not the best scholar in the world. If you put a written version of a song she'd sang all her life in front of her, it doesn't mean anything to her at all.

In fact, there was an occasion at a lovely singaround at Sutton [West Sussex] when she stumbled over the words of a song that she was singing. It just so happened that Russ [Godfrey], who used to run the Chichester club had opened one of my books and was following the words of what mum was singing. Now, when mum stumbled over the words, he put a written version in front of her. It didn't mean a thing to her. In other words, if you put a version, the words, my mother would read it, painfully, but she wouldn't read it and sing it. Very often, she wouldn't realise it was the same thing as she had sung all her life.

So you obviously feel that she has absorbed the songs in the same way. So where from? Her mother? Where did Mabs learn her songs?

If you get to the history of how Mabs absorbed her songs ... My maternal grandmother, I was never lucky enough to meet, a wonderful woman, as I understand it, knew hundreds of songs. But according to Mother, she would only sing snatches. A woman so full of life that when I tell you she was still having children at fifty-odd. And died as a very elderly lady without a grey hair in her head. Really full of joie de vivre, if you like. This is how my mother explains it. She has done enough work to kill ten horses, my mum, but she says, 'Whatever I have done in my life would only be a fraction of the work that your grandmother did.'

Then, of course, we get to Jesse, my maternal grandfather. Jesse was something of a contradiction, if you like, in the traditional sense, in that he was, in brackets, 'educated' . He was a farmer's son. I don't know the way of business they was in, but he had a tutor. Now, that sounds very grand, doesn't it? I imagine what he was, was the local teacher that would supplement his income by giving some tuition to my grandfather. Now he, on the other hand, everything he sang, he sang full versions, if you like. I should explain that my grandmother was completely illiterate . You know, it's lovely to see, a copy of my mother's birth certificate, signed with my grandmother's cross. I mean, we don't think of things like that. And of course, when my mother picked up a book, you understand, this was in the days when candles had to go out and oil lamps had to go out at a certain time of night from sheer economic pressure. My grandmother would actually knock a book out of my mother's hand. she wouldn't allow her to read. This was the work of the devil - books! Now it might be simply that because she was illiterate herself, she was jealous of the fact that Mum could, after a fashion, read.

But the old man, Jesse ... Well, it's a family joke. When he was able to help somebody with some paper work, when my mother was a young woman. The chap - I hope you don't think I'm patronising when I say this -but the chap who obviously couldn't write that Jesse had helped out, said something like, 'If I'd have been as good a scholar as you, I'd have been in the Houses of Parliament years ago.' You know, that's how things were in the country, weren't they?

What part of the country would Jesse have been bringing his family up?

Well, I think they were fairly mobile. Mum was born at Cheel's Cottage at Wivelsfield. I haven't had time to research it, but I can't find Cheel's Cottage, Wivelsfield, in the general area of where Mum remembers that she lived. There is a Jenner's Cottage. Now, Jenner was the family name, so it may well be that it's been changed from Cheel's Cottage to Jenner's Cottage. I certainly wouldn't have disturbed the people that lived there with a question that they may not have had the answer to, if you take my meaning.

But, as a youngster, you lived in London, didn't you?

Well, I lived the first eight years of my life in London and all of us, and there were six of us, were all born in and around the Borough of Greenwich and we lived in Blackheath Road, which was my paternal grandfather's house; he being a musician who went to sea as a bandmaster, or if you like a musical director for the Union Castle Lines. I haven't had too much time to research, but I do have a cousin Frank, who lives locally and has some of the music that my grandfather left behind. All I can tell you is what my father used to say about his own father. He was something of a martinet, a very good musician, and when he held the auditions for the band that were going on the vessels, the Union Castle boats, he would literally snatch the instruments from the musicians and show them, whatever the instrument was, according to Dad, would show them how he wanted a particular passage of music played. In fact, my father, who was something of a rebel, used to say that had the old man done it to him, he probably would have ended up with the instrument across his nut! But that's the way me father was.

Was your father a musician as well?

No, but he was a singer in the sense that if I've ever heard anybody caress a word in the way my father did ... And of course, he was a Cockney.  So his voice lent itself to songs of the sea, shanties for want of a better word, music hall songs - because in his time he had been a 'Buttons' at one of the London theatres - comic songs and, of course, parodies, and the old army songs were his favourites. A lot of which we learned from Dad, when he was in the mood to sing them.

So his voice lent itself to songs of the sea, shanties for want of a better word, music hall songs - because in his time he had been a 'Buttons' at one of the London theatres - comic songs and, of course, parodies, and the old army songs were his favourites. A lot of which we learned from Dad, when he was in the mood to sing them.

You've talked to me before about what these songs mean to you, how special they are You've been asked to sing them at festivals ...

It's very, very difficult, because it can be embarrassing, not necessarily for me, because I'm used to being stirred emotionally,but the effects on other people, outside the family. A grown man weighing nearly twenty stone sitting there with tears

coursing down his cheeks, and very often getting so choked up that you cannot carry on. That is, in a sense, an imposition on my part on the people that are listening . People don't necessarily understand and you can't ... well I can't fake that.

You know, I can see those boys, I can see my Uncle Fred, you know, being captured. One of only 38 men that were captured out of the Sussex Regiment that the Germans called 'The Iron Regiment.' Only 38 of them. Now if that's not a personification of the 'We Won't Be Druv' which Sussex is all about. They got killed in their thousands - 1,723 of them from the 2nd Regiment alone. That was my uncle's and my father's regiment. It's just incredible to think that there they were. They had that stoicism in spite of what was thrown at them. And, not to put too fine a point on it, they were very badly led and they weren't that well kitted out. You could argue that this was the first modern war of its kind. The first modern war, but it infuriates me to think that perhaps, if circumstances had been slightly different, many of those poor souls that died would have come back to us.

So, if your father was in a Sussex regiment, had the family moved back to Sussex or had he joined the Sussex Regiment in London?

Well, what in fact happened, and it's quite an unusual story ... My father was in the army at the age of 14. I think he was wounded before he was 15 years of age. And then, as a result of his other brothers - he was from a fair-sized family - my uncle Bill, I believe he was an early despatch rider, and somewhere or other he came across his younger brother, who, as in the words of the song, he thought was safe back home. Well, he made it his business to see that Dad was sent safe back home.

So then Dad waited until he was 16 years of age. I beg your pardon, I should have said that at 14 he joined one of the Lancer Regiments. And to the day that he died he talked about the screams of the horses as they were cut to pieces by shrapnel. That was something that was burned into his memory. Anyway, he then rejoined the army at the age of 16, this time in the Sussex Regiment, and he served alongside other people, for example, my Uncle Fred, Mum's brother, the next one up in the family from Mum. They was from a big family, but mainly girls, just two sons: Uncle Fred, slightly older than Mum, he died fairly recently, he was well into his eighties, and Uncle Will, who was killed on a motorbike on Clayton Hill about 1926. I've never been able to confirm that, but that's the family story.

So Dad was in the Sussex in the second battalion, of course, it was a terrible business. You would not believe this, but at the time when my father ... we always had a huge table because there was a crowd of us ... at a certain time of an evening, my father would adjust his chair at the head of a big old refectory table, because he dealt in furniture, to a certain angle and you knew then that we were going to be on the receiving end of all those, wonderful to us, war stories. Obviously, after a while, you could have told the stories in exactly the way that Dad was telling it, except that he was a wonderful raconteur, me father, arguably the finest teller of a story that I have ever heard in my life. Now, when I say that, I don't want you to get the impression that he changed his dialect or his accent. He was always the loveable Cockney. That's the way he was made. But he had a feel for language. He could make himself understood in any company without altering his accent and, I mean, you lived through it with him. If Dad talked about, in his rather colourful language, when they retreated from wherever, we'll say Mons: 'There we were, the rags of our arse flogging us to death.'

And they put the regimental band in front of them. Well, of course, by this time the lift that you are supposed to get from the regimental music that conjures up the Jingoism or whatever, they'd got over that, you know, and in fact they used to sing Sussex By The Sea which was their regimental march:

Dear Old Sussex by the Sea - I've shit'em.

Nothing against the people in Sussex, except that they knew that nobody over here, be it in Sussex or in any other county, knew what was going on at the Front.

You know, girls were walking about giving people white feathers, weren't they? That kind of thing. They had no idea of the hell it was. No idea at all. And of course, there it was. In fact, I did add that one experience along with others into one of the old army songs that we sing:

No more army bands a-playing,

Dear Old Sussex By The Sea,

While your legs and feet are rotting,

With trench feet up to your knee.

Oh ... [long pause]

Let's bring you back to some happier times, Gordon, because I can see you are being affected by an this ... When did you move down here to Sussex?

Now, we left London as a result of the Blitz. I can remember picking up shrapnel. In fact, it was my introduction to the scrap trade, as a little boy. I could only have been about eight years of age, I and the local lads, the hounds, if you like. We had an old doll's pram that we used to fill up with the shrapnel which was laying all about your garden, the pavements, the roads, etc., and we'd run it down to the local scrapman and we'd get a few coppers for it and back for another load and that was my introduction to the scrap business, as it was everywhere. And, of course, there were the odd mornings when you went running around for a pal and the houses that we were living in at the time were surrounded by fairly high privet hedges, not too many gardens in that part of the world, and you'd be through the hedge - I mean, I was quite tiny - before you'd realise that the house that had been there the night before was no longer there and your dear old pal at school was no longer with us.

But we went on our travels rather, then. We were briefly in Wales. Leeds for a little while, a lovely warm place, it really was. That was really marvellous for me because I heard people speaking Elizabethan English. The 'thee' and the 'thy' that I'd had problems with when I was singing the old songs, there it was. And it came out so easily and so beautifully. 'Thou art afoot!' - the first thing that anybody ever said to me in Yorkshire because I'd transgressed some little thing at school. And it rolled off the tongue and it was beautiful to me, and I can never understand to this day why the educationalists tried to suppress the lovely dialect and accent. When you think what a beautiful language and accent you've got, and how much more varied it is as a result of all these lovely nuances, even down here in Sussex.

At one time when I was dealing with two or three hundred people in a day in business, I would take it upon meself to tell a fellow where he came from by the way he talked. And Brighton was the favourite. I'd say 'You come from Brighton'. And the chap would say, 'Yea, I know I come from Brighton'. Then I'd tell him what side of the pier he was born on. You could pick it up with your ear - you know, from the way he said his 'a's. I'm not a mimic but I could tell from the voice. And with the Midlanders. Sometimes, when I was in the coal business, I would tell the drivers that brought the coal down from Nottingham or Leicester or wherever they came from - Derbyshire - what village they lived in or whatever county, only from hearing another fellow from the same place. Look at the name on the side of the lorry, you see, and this fellow would sound exactly the same in some words and I'd say, 'Well, you are not very far from so and so', and very often they'd think there was something strange about you, being able to tell them this.

So it sounds like you've really got the mind for picking up what voices are doing. It must be relatively easy for you to pick up songs?

Well, if you are talking musically, probably not. My mother, she says that I sound like a pig chewing cinders!

As good as that, eh?

But there are certain nuances of tune that I could never get the way my mother sings them. It's been a source of great frustration to me over the years. I might be within a twopenny bus-ride of the tune but, as I said to you before, I think my link with the tune is somewhat tenuous anyway.

I've always thought that you carried a tune well.

Well, I'm very pleased to hear that, but all I can say is, if you had been fortunate enough, and I'm going to use the word fortunate, privilege almost, to hear my mother sing when she was a young woman and to hear my brother sing, even to this day ...

This is Albert?

Albert [French pronunciation] because he lives in Normandy. He sings so many French songs, you would not believe it. Since 1945 I've been parroting alongside him and it's only since I've got the translations that I've now dried up because I'm quite convinced that the written words cannot correspond to what I've been singing for, well, whatever, since 1945. It's lovely. Lovely links, you know, wonderful links between some French songs and our old English songs. You know, you think of: You seamen bold, that plough the ocean, know dangers landsmen never know.

And the French song tells exactly the same story, somewhat embellished, because being Frenchmen it's not enough to cook a man, you've got to decide how you are going to cook him and what sauce you are going to use. But the same French song is:

Il tait un petit navire

Il tait un petit navire

Qui n'avait ja- ja- jamais navigu

Qui n'avait ja- ja- jamais navigu

O-h! O-h! O-h! O-h! Matelots,

Matelots naviguent sur le flot,

O-h ! O-h! Matelots naviguent sur le flot

And so on, lovely song. When you get a crowd of us singing that, it's one for the neighbours, you know what I mean?

Let's have You Seamen Bold in full now.

Oh no, I couldn't. I'm not sure I could sing it all. it's just little phrases that have stuck in your mind as a kid, you know. I'd like to, it's a lovely song. It's interesting too, because although the version that me brother sings of Petit Navire centres on the Mediterranean - that's where they are headed for, which is quite a voyage, because apparently it's quite a small vessel that the Frenchmen set sail in - they finish up on the coast of Guinea. And I was fortunate enough to have an old pal of mine sent me a version from a French aunt of his where they were headed for the coast of Guinea. It's lovely stuff.

You mentioned working in the scrap metal trade. You must have been in that trade for quite a number of years.

Well, off and on. You see - if you had a big family like Dad did, see, you had to keep your eyes open and earn the best way you could. I've known my father work 24 hours a day as a regular thing. He'd work all night at the Woolwich Arsenal, for instance, tempering gun barrels and then up to Hounds Ditch, fill up his little van, out to Maidstone market for the rest of the day. If he was lucky, he'd get an hour in the chair before he went back on shift at the Woolwich Arsenal. He kept that up for quite a while but he finally succumbed to gallstones, which was a massive operation in those days. Of course, he was as tough as old boots, I mean, really. Dad came home, put his suitcase down and his tummy burst open. It never went back for the rest of his life. When he stripped to have a shave - he was a very stiff built man, solidly built; not as tall as us in the main, but very, very heavily made, arms like legs ... and one side of his tummy ... you know how your tummy muscles are, or at least how mine were not too long ago, the division between them, well, that's roughly corresponded with the cross of Lorraine, if you like, it was the cut for that operation in them old days - and one side, I suppose it stood out two inches from the other. It never went back. He was told he would never ever work again. Shortly afterwards, of course, he was humping two hundredweights of coal, which was another business we used to get involved in.

But most of the work that I've done has been heavy manual work. Some of it unpleasant, because, generally speaking, it was either piece work or there was a bit more money involved than with normal work. Generally, I've worked freelance. I've run a scrapyard as a freelance. I've done navvying piecework. I've drawn bricks piecework as a youngster, drawing them out of the fire, that kind of thing.

I've loaded boats at Newhaven. I've worked with every race in the world including the Greenland Eskimo. A wonderful little man - I can't remember his name - was with a vessel that we were loading and there was this lovely little fellow, continually smiling, and he was orange, he wasn't red. you hear people say 'Red Indian' but he was a marvellous little fellow. I think the story was that the owners of the vessel were Italian. They have been doing some work associated with the development of the oil in Alaska and whether they picked him up there I don't know, but he was a Greenland Eskimo. So I can justifiably say that, though of course they were only for a day or so, it didn't take long to load them. I can say that I have worked with every race in the world. It was my proud boast, at one time, that I could say 'hello' to most people in their own language, but most of that's gone. I can't even speak English now!

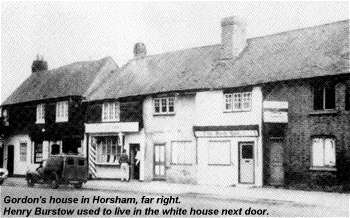

I've heard you talk a lot in the past about Horsham being a place that's very close to your heart. That's a place that's had a strong association with traditional singers.

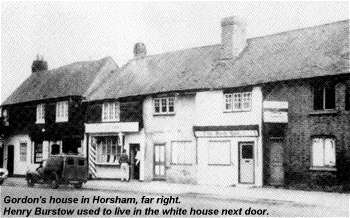

Well, that's true. We came to Horsham first to live with my Uncle Fred, my mum's older brother, and we lived under the same roof that Henry Burstow lived under.  We didn't realise that at the time, of course, but my younger brother Lester and I were asked by the landlord of the whole property. It had been in its time a pub called the Jolly Ploughboy. By this time it was five separate dwellings including one front room that was used as a barber's. I can't remember his surname but his given name was Jack. He was a splendid fellow. It was five or six doors opening on to the Bishopric. Now, one of these front doors didn't open and thereby hangs a tale, because me younger brother Lester and I were asked by the landlord, Mr Walter Etheridge, would we knock down a nailed up door on the inside of the building. We did that and it opened on to this little front room which was, in fact, a tiny little shop and for years we could never figure it out. The shop was later rented by a Mr Sears, who was an antique dealer. This shop had shelves all around it, but very shallow shelves - they were only about two inches apart - and it was only when I read in the reminiscences of Henry Burstow that I realised that that was the pipe shop that Mr and Mrs Burstow raised the eleven or twelve kids in. Most incredible. I could tell you a story about what happened to me when I lived there but you'd probably think I was a raving lunatic. For the duration of the time we stayed there with Uncle Fred and Auntie Ruth, I drove everybody mad with a tune, not the song, but a tune - [hums] - 'til everybody in the family said to me. 'Oh! For God's sake, either put some words to it or shut up! ' Now, I privately think that was old Henry trying to tell me something.

We didn't realise that at the time, of course, but my younger brother Lester and I were asked by the landlord of the whole property. It had been in its time a pub called the Jolly Ploughboy. By this time it was five separate dwellings including one front room that was used as a barber's. I can't remember his surname but his given name was Jack. He was a splendid fellow. It was five or six doors opening on to the Bishopric. Now, one of these front doors didn't open and thereby hangs a tale, because me younger brother Lester and I were asked by the landlord, Mr Walter Etheridge, would we knock down a nailed up door on the inside of the building. We did that and it opened on to this little front room which was, in fact, a tiny little shop and for years we could never figure it out. The shop was later rented by a Mr Sears, who was an antique dealer. This shop had shelves all around it, but very shallow shelves - they were only about two inches apart - and it was only when I read in the reminiscences of Henry Burstow that I realised that that was the pipe shop that Mr and Mrs Burstow raised the eleven or twelve kids in. Most incredible. I could tell you a story about what happened to me when I lived there but you'd probably think I was a raving lunatic. For the duration of the time we stayed there with Uncle Fred and Auntie Ruth, I drove everybody mad with a tune, not the song, but a tune - [hums] - 'til everybody in the family said to me. 'Oh! For God's sake, either put some words to it or shut up! ' Now, I privately think that was old Henry trying to tell me something.

A Blacksmith Courted Me?

Yes, or Our Captain Cried All Hands. You see, I'm firmly of the opinion that those two are the same song. Not everybody's prepared to listen to my theory on that.

Could you sing that for us now?

[Long pause.] No, I think I'll give that one a miss. You see,I'm not entirely convinced about the way people sing that these days. But,of course, I've got to say this. It's only since - Mum's 84 - so since 1984 that I'm so interested in the old songs . I want to find out as much as I can about every song I've ever heard and trying to delve into them. In the case of some of the big ballads, to try and find out how true they are to the living history . I mean I sang earlier Lord Randolph. Well, I'm given to understand that Lord Randolph was from your part of the world and so the scholars tell us that he may well have been Thomas Rendell or Randall or Randolph, nephew of Robert the Bruce, who died in 1332 or something like that. Now, I find that fascinating. It might be quite wrong, but I do find it fascinating, that kind of thing.

So the ballads hold a particular fascination for you?

Yes, because... I've got to say this. Somebody once said to me after I'd sung twenty or thirty verses or whatever. I think it was Lord Beckett in this case, when someone said to me afterwards. 'Do you tell stories?' And I said 'Well, I thought I'd just told one!'

That's what a ballad does.

Well, hopefully, yes.

You perhaps don't like to trade in numbers, but how many songs would you say you know? How many songs in your repertoire?

I can't say that for two reasons: (a) I don't honestly know how many songs I know, and (b) if I told you, you probably wouldn't believe me anyway. Let's put it this way. When I read about the singing machines, etc., that whoever wrote about them thought they were unusual, I wouldn't think they were unusual the number of songs they knew. Is that a good enough answer?

Henry Burstow certainly knew hundreds. Do you?

In fact, I've recorded over 200 hundred songs that I sing. When I say recorded, it sounds very grand. What I've done, I've sung into a microphone in me own front room and rushed across to switch it off and generally made a complete balls of it, but then I know lots more. In fact, I passed on to dear old Keith Chandler, a hundred and odd songs to see what he thought of them and really, he ought to have a medal struck for him that he's sat and listened to them, I believe all of them! But I do know a lot of songs but I don't think there's anything unusual about that to someone like myself. I mean, we are not dealing in numbers. It's not important, but since I've begun, if you like, to expose myself - now that sounds mildly wrong, doesn't it? - to what's going on in the scene that you realise there are a lot more songs, some of which you didn't bother too much about. I mean I'm only just beginning to realise that the songs we sang as school children ... bear in mind, I've got three elder brothers ... that we sang at parties when we were young because we thought they were 'go-y', in fact were quite highly regarded sea shanties Now, we obviously didn't see them as work songs, they were just damn good songs, you see, but there it is. They were fun songs to us.

So the songs would come up at parties at home. Would they be sung the rest of the time as well?

Well, perhaps I ought to have explained earlier that as a family we are compulsive singers. Mum, even today, ninety-plus, as she walks down the street ... When we worked as a family delivering coal, we would sing, running with two hundredweight of coal on our backs. You might have me eldest brother doing one of the arias or Pretty Polly Perkins whilst we were unloading coal trucks. Everyone thought we were quite mad. I'm sure that when Mum goes along singing to herself, along the road, because she still steps out quite briskly, I'm sure that when people can't hear, but they can actually see her lips moving that they probably think she is talking to herself, ga-ga, and she's far from that, you can take it from me. You cannot expose my mother to an air, a bit of music, but she's either got a parody or a set of words to it. I listened to her the other day. I crept into the room, because I thought she was asleep and it just so happened that Mr McPeake's son was on the telly. Frank McPeake, I think he's called, from Belfast, a wonderful musician, and I think he was playing what I now know to be the Valse Vienne, and I only know this because I rung Reg Hall about it, and there was me mother singing to herself:

Cock your leg up, Sal Brown, Let your waters run down.

Cock your leg up, my dear, Let your waters run clear.

As soon as she became aware of my presence, that was the finish of it. See now, I can't tell you if there's any more to that and I certainly won't learn it from mum! because she's still very ... very ...

So you learned that one by accident?

Absolutely. Never heard her sing it before. Whether there's more of it I shall never know. There was a thing in the family ... there'd be army songs or what people call rugby songs today. They were perfectly acceptable, provided there weren't any females about, so when the girls were doing the washing up, we generally lived in big old houses, they'd be out in the scullery or kitchen and then, of course, you'd have The Bastard King of England or whatever . Well, the girls had their risque songs, presumably, and the lads would have the same. Of course, if a girl got up and sang a risque song, well, she set the standard, of course, so then you'd carry on. Then you'd perhaps do the 'suspended chain' to leave out some words that were unacceptable. You still do it today.

It's rather strange that when I was asked to record a couple of songs for Roy Palmer's lovely book, I was insistent that they were printed as they were sung, but when it came to recording them, I found that I couldn't f..... and blind as I would in an all-male company, so you had to sort of substitute words, or suspend it and leave it out, whatever, and I can't really say why because one never had any compunction at ... one or two of us were rugby players and we would sing at beer-ups or whatever in the army and wouldn't think twice about it. But I just couldn't ... I think, in fact, that Roy Palmer said I was very gentlemanly about it, but I don't know if that is quite true.

So you sang at rugby clubs and in the army as well as at home. Did you also sing in pubs?

Very few. Well, I've sat through many a sing-song and I haven't contributed. Curiously enough, I did some work on the demolition of the railway from Lewes to Uckfield and the chaps that took that work on were from Gloucestershire and they all liked a good old sing-song and we went into the Talbot Arms in the bottom half of Lewes. I might be wrong about the name. And that was quite interesting because the job went on for a week or two and we spent most of the evenings in this pub. The landlord was an ex-Canadian bandsman and he'd rattle out a tune with his drumsticks on the counter and we used to sing there, much the same as a singaround, good old boozy sing-song, music hall songs, comic stuff, some very frankly rude songs, and on one occasion we did a thing that we sang to include everybody in the pub. I must admit that we cheated rather because we did in The Stores. So there was Jill, who was firmly on the pill, etc., etc., and then one or two other songs, What's Your Name, or whatever, and then a lovely lady came up to me and I think her name was a Mrs Carter and she said, 'I'll have you know,' in her lovely Sussex accent, she said, 'You ain't got a song for me.' And I said, 'What's your name, my dear?,' and she said 'My name's Cis'. Well, immediately you can imagine the lads from Gloucester, you can imagine what Cis was doing in the corner of the Stores, you see, and I said, 'Well, as a matter of fact, my dear, I might possibly have a song if you can tell me what Cis stands for.' And believe it or not, she said, 'My name's Cecilia.' Now Cecilia is arguably my favourite song of Mum's. The first song, possibly, that I ever heard and certainly the first that I can remember singing, having absorbed it - you don't learn them, you absorb them.

And how does it go?

Cecilia, on a certain day,

Did dress herself all in man's array.

With a brace of fine pistols hung by her side,

To meet her true love, to meet her true love,

To meet her true love away did ride ...........

Lovely. Now that would be a song that I've heard a lot of people singing but, like a lot of the songs that you sing, it's always a very full version. You always seem to have a very complete text. Now why ...

Jesse - Grandad - I'm convinced. Mum will say, mother never used to sing a song through. Dad did and often she shed a tear and that well may be because of the way I sing 'em but she'll still say 'That was Dad's song.' That's it for sure.

If you take the version of The Molecatcher that you sing. It starts before the story that most people have and goes on after most people have finished.

Yes, well, in the case of The Molecatcher there's a little bit which I tack on the end which Gillian's Uncle Phil is responsible for. Now, he's a Suffolk man and he knows all the old timers that you read about in the books. 'Shirt' Burrows, Oscar Woods, etc. He goes out even today with a washboard and whatever, a gigglestick. He's a good old tum, old Phil, and he gave me the little bit about the tomatoes.

When tomatoes are ripe, it won't break the skin,

But this bugger did, it was still in the tin.

But I do cheat slightly with The Molecatcher because, as I tried to explain earlier, you've got to have a way of putting it over without driving everybody mad. So if you can start with, what, for argument's sake, The Week After Easter:

The week after Easter, the weather somewhat thin,

I met an old 'omiker ugly as sin.

... and then you work into The Molecatcher, you see. You know what an 'omiker is don't you?

No, I don't

An 'omiker. Well, briefly I used to drag the bricks out of the kiln. It's a homiker, because as you know we don't use aitches in Sussex so it's an 'omiker. An 'omiker is the bloke what used to do the bearing off. Now, 'bearing off' is taking the handmade bricks that were dried initially in the sun on ... well, rather like a Chinese wheelbarrow, single wheel in the middle with two long planks either side and that's what you bore off the hand-made wet bricks ... and you stored them out briefly to get a bit of sun before you put them in the clamp to burn them. So he had a bearing off barrow and he was an 'omiker. So the 'omiker becomes part of The Molecatcher.

And, of course, I sometimes put several verses of Farmer Giles in front of it again, you know, to ring the changes, plus I like 'em. I like both songs.

So when you sing a song, the words aren't settled, The words will change according to what, your mood?

Well, I'm always more interested in the story. As long as you keep the story line ... I don't want to sound as though I'm making it up, but, in fact, it is possible when you know an awful lot of songs. I mean, I know that sounds as though I'm swanking, but I mean in the same way as people talk about 'floating verses', you don't really write a song, you see, if you know a lot of old songs, you just borrow, if you like. It's an unconscious plagiarism. As you know, many of the songs are made up of floating verses. They belong to a dozen different songs, some verses.

And some of the phrases are settled as well. Milk-white steed ... As white as snow ...

Well, you've got to get the metre of the song, but I mean, as a child I was very interested in one thing of Rudyard Kipling's, The Smuggler's Child, and I've sat down briefly and thought, 'Well, how would my old grandfather have sung that?' And I've added a couple of verses to bring in a bit of local knowledge about poor old Dan'l Scales who was shot at Patcham and he's in Patcham graveyard, where his epitaph is, I believe, 'Unfortunately Shot,' which gives you an idea about how the locals felt about the revenue men. I've sort of added that and roughly it's a few verses, if you like, added to Kipling's Smugglers Song. I've slightly altered it because I feel it's in the interests of historical accuracy. He says 'five and twenty ponies' ... I think I say 'five and forty ponies', things like that, you know. And I've made the story, it's an old grandfather, a fond grandfather telling his granddaughter how to go on so that she doesn't transgress the code and she doesn't get her two brothers suffering the same fate as Dan'l Scales. it's just a thing but I can't honestly say ...

I didn't sit down and write it. I just sang it. I have written it down now, obviously, but I was never conscious of writing it. It's just come out and I've done one or two things like that. I was in Eyam in Derbyshire walking around with a local guidebook and I started to sing the tragedy of the plague at Eyam; actually walking around. And then, believe it or not, we went back to the lovely hotel we were staying in, in Harrogate I think it was and wrote down the same night and then promptly lost the bit of paper. So I can only remember about the first four verses of it. Believe it or not, I used the old shanty tune of The Shaver.

I can't say that I wrote that song, it just occurred to me armed with the information in the guide book. Would you like to hear what I can remember of it?

I would do.

Well, I'm not sure you will when you've heard it, but there you are. Let's see if I can remember as much of it. I don't suppose I'll ever find it. I shall have to get the guide book out again.

In the village of Eyam, High Derbyshire,

Sixteen hundred and sixty-five was the year.

A dreadful sickness it did appear,

Singing ring-a-ring-a-roses, a-roses

Sing ring-a-ring-a-roses until we all fall down.

To the journeyman tailor, George Vickers by name,

A bolt of cloth from London came,

He stored it for to dry the same

When that wool was by the fire arrayed,

How those black rat fleas they skipped and played,

Then they jumped and buried both man and maid.

And then it goes on to George Vickers died first, George Hawksworth and so on and so on, about twenty verses. Unfortunately I've lost them.

But there's not a syllable there that wouldn't occur in a traditional song or a broadside. Obviously you've totally absorbed that.

As I say, I didn't write it. I sang it first and only after that did I write it down.

It wouldn't be the same song if you'd written it down before singing it?

Well, possibly. I don't believe anybody writes a song. How can anybody be responsible for what goes on in your brain. God puts it there, I mean, I think good luck to anybody that makes a fortune out of writing a song, but we don't write them. They are put there for whatever reason. Whatever the reason is.

This is what interests me about the reportage songs that actually tell of a historical happening. I mean, for argument's sake, the little old song that Mum sings about the loss of the Royal George. I think that's more historically accurate as regards the numbers of casualties than the written history. I'm convinced of that.

It's a great song. Could you give us that one?

It's a nice little song, but you've got to be in the right sort of mood to sing it. It's a song I'm very fond of. I was very surprised when I went to Greenwich museum trying to mug up on it. Of course, they didn't know anything about it, but they still insist that 1,200 was the top whack of people lost there and Mum, of course, sings about 1,400 men, women and children and only four got safe on shore. Well, historically, as far as I understand it, four, that was absolutely true, one of which was a little boy that they didn't even have a surname for so how could they possibly have known the size of the family that he was with, for argument's sake, but anyway, it would drive you mad talking about it.

There may have been a Political interest in not declaring the correct numbers?

Well, obviously they'd be a bit shy of that. But they should have been shy. you see, that vessel was as rotten as a pear.  I'm never sure how to pronounce it, but that vessel was infested by the teredo worm and it was literally ... well as you know, they tunnel longitudinally and the thing was falling apart and they put a copper bottom on that vessel, over the rotten timbers. And it really was ready to fall apart at one time.

I'm never sure how to pronounce it, but that vessel was infested by the teredo worm and it was literally ... well as you know, they tunnel longitudinally and the thing was falling apart and they put a copper bottom on that vessel, over the rotten timbers. And it really was ready to fall apart at one time.

And it's a matter of historical fact that they didn't want it to be salvaged. People made various attempts but it was the first time in our history that what we know as a diving suit was made. And, as a lovely offshoot of how that came about, as a result of a young man in Kent with the farmhouse on fire, he grabbed an old parliamentary helmet from the war and he used that to breathe within like a diving bell and rescued the horses from the stables or whatever, and then later on, as he got older, he made a diving suit of sorts, which he used to try to reclaim or salvage the Royal George.

And it was fairly obvious that the naval authorities at the time, they weren't too keen on having it salvaged and, in fact, they put various obstacles in his way and he gave up and when he gave up, the Navy, in their wisdom, briefed an old army captain, an artillery officer to blow it asunder to make sure that it couldn't be salvaged. Because there it was for anybody to see, lovely copper bottom over a rotten vessel. You know the story where they heeled it over to do some repairs and it just turned turtle ... I find that kind of thing interesting, but people think I'm just an old nut!

In the last few years, you've been singing in the company of other Sussex singers that have songs in their families. People like Bob Lewis and the Coppers and so on.

Lovely singers.

Over the years have you sung with many such people? People that have never or would never sing in clubs and festivals?

Well, I've been in the presence of them, not necessarily sung with them, but if ever I've heard something that I've identified with, naturally I've listened. I've heard some wonderful stuff. I mean, I'm firmly convinced that every family in the county had singers and a repertoire of songs and it's only when you uncover ...

I'll give you a for-instance. A very dear pal of mine, a schoolboy chum, in fact, I actually knew his father-in-law and he wouldn't necessarily know that as a family we sang the old songs, but he arguably ... well, his grandson salvaged a tape from a party, which should be required listening for every revivalist singer. Because there is this lovely old man, 84, I think, the year before he died, and it's absolute pandemonium, a wonderful family party with about three or four generations. The noise is chaotic. Nobody's lowered their voices. They are all going about their business yelling, 'You got any more beer?,' this kind of thing. And the old-timer is soldiering on. One of the funniest men I've ever heard in my life, a major singer in every sense of the word and I really mean it! Absolutely tremendous! And one of his songs, as I say, very difficult to decipher because he was elderly, but he had that lovely Sussex habit where he would speak a line, sing and speak, shout if it was called for, change from singing to speaking to shouting if it was a command, do you understand me? And, of course, overall the most marvellous, what I call North Sussex dialect and absolutely ... I mean, a privilege and yet I knew him for several years and he knew me for several years, the question of the old songs never came up between us. And I've still got this lovely tape which I'm so grateful to his grandson for, and it's a song that I sing now, one of the few that I sing that comes from outside the family, and it's a lovely song. It's sort of based on Oh! Dear, What Can the Matter Be?, and I can't pretend to do it as well as Mr Gates. Mr Arthur Gates, his name was. He was born in Faygate and he'd served in India, but it's a lovely old song. So that old song, I use our family chorus for Oh! Dear, What Can the Matter Be, and his verses.

Now, I can't do the song justice because I would have to be eighty-odd years of age and I would have had to have lived every minute of my life, apart from my army service, in Sussex. But it's most wonderful; well, I think so, anyway:

Sings Oh! Dear, What Can the Matter Be .......

Just imagine a man that had sung that song and dozens of others and nobody had heard of him as far as I'm aware although I think there was a link between him and Bill Agate who was busy in the Rusper area, because Mary, that's the daughter, the wife of my dear old pal, she talks about him going out around Colgate, Faygate, Rusper and places like that, when he came back from a long service in India. But wonderful.

Everywhere you went, as a for-instance, right down opposite where Henry Burstow finished his life, in Spencers Road in Horsham. Now, my mother- and father-in-law, Ted and Eva Daniels, lovely couple, when I first asked them, did they know Henry Burstow ... Now, they are both lovely Sussex people. Grandfather, Ted Daniels: 'Ole 'Ener'! Bloody sure I knowed 'im'. Because, of course, he would have been about sixteen years old when Mr Burstow died.

Now then, almost opposite in Spencers Road was Aunt Jessie. Now, Aunt Jessie had such a voice, the lady's voice that sounds almost like a man's and so powerful, it wasn't true! My wife, God rest her soul, and her sister who is still married to my younger brother, their job, when Aunt Jessie started singing, was to go to the gate, one to go up the road and one down the road and to come back and report how my streets away they could still hear Aunt Jessie. A wonderful voice in the true sense of the word. You know, an operatic voice.

And, you know, everybody had a song, a number of songs. I get a little bit peeved at the impression that the collectors gave that it was only by diligence that they dug out these people who sang the old songs. I don't believe it to be true. Even today, I'm convinced that there must be dozens of families like ours that are still about and nobody will ever hear them outside the family because it's not in them to sing outside. They are quite happy to sing at home as I am, to sing all day. That's the reason I've got no voice. Singing like that - driving everybody mad. We've had more neighbours than anybody on earth.

Vic Smith

Gordon Hall can be heard on the cassette In Horsham Town (Veteran Tapes VT 115)

Article MT049

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 10.10.02

The conversation got round to what his songs mean to himself and his family, so, after a brief welcome and an introduction, that seemed to be a good point to start the interview ...

The conversation got round to what his songs mean to himself and his family, so, after a brief welcome and an introduction, that seemed to be a good point to start the interview ...

It's incredible. I've got to explain to you ... Mother is not the best scholar in the world. If you put a written version of a song she'd sang all her life in front of her, it doesn't mean anything to her at all.

It's incredible. I've got to explain to you ... Mother is not the best scholar in the world. If you put a written version of a song she'd sang all her life in front of her, it doesn't mean anything to her at all.

So his voice lent itself to songs of the sea, shanties for want of a better word, music hall songs - because in his time he had been a 'Buttons' at one of the London theatres - comic songs and, of course, parodies, and the old army songs were his favourites. A lot of which we learned from Dad, when he was in the mood to sing them.

So his voice lent itself to songs of the sea, shanties for want of a better word, music hall songs - because in his time he had been a 'Buttons' at one of the London theatres - comic songs and, of course, parodies, and the old army songs were his favourites. A lot of which we learned from Dad, when he was in the mood to sing them.

We didn't realise that at the time, of course, but my younger brother Lester and I were asked by the landlord of the whole property. It had been in its time a pub called the Jolly Ploughboy. By this time it was five separate dwellings including one front room that was used as a barber's. I can't remember his surname but his given name was Jack. He was a splendid fellow. It was five or six doors opening on to the Bishopric. Now, one of these front doors didn't open and thereby hangs a tale, because me younger brother Lester and I were asked by the landlord, Mr Walter Etheridge, would we knock down a nailed up door on the inside of the building. We did that and it opened on to this little front room which was, in fact, a tiny little shop and for years we could never figure it out. The shop was later rented by a Mr Sears, who was an antique dealer. This shop had shelves all around it, but very shallow shelves - they were only about two inches apart - and it was only when I read in the reminiscences of Henry Burstow that I realised that that was the pipe shop that Mr and Mrs Burstow raised the eleven or twelve kids in. Most incredible. I could tell you a story about what happened to me when I lived there but you'd probably think I was a raving lunatic. For the duration of the time we stayed there with Uncle Fred and Auntie Ruth, I drove everybody mad with a tune, not the song, but a tune - [hums] - 'til everybody in the family said to me. 'Oh! For God's sake, either put some words to it or shut up! ' Now, I privately think that was old Henry trying to tell me something.

We didn't realise that at the time, of course, but my younger brother Lester and I were asked by the landlord of the whole property. It had been in its time a pub called the Jolly Ploughboy. By this time it was five separate dwellings including one front room that was used as a barber's. I can't remember his surname but his given name was Jack. He was a splendid fellow. It was five or six doors opening on to the Bishopric. Now, one of these front doors didn't open and thereby hangs a tale, because me younger brother Lester and I were asked by the landlord, Mr Walter Etheridge, would we knock down a nailed up door on the inside of the building. We did that and it opened on to this little front room which was, in fact, a tiny little shop and for years we could never figure it out. The shop was later rented by a Mr Sears, who was an antique dealer. This shop had shelves all around it, but very shallow shelves - they were only about two inches apart - and it was only when I read in the reminiscences of Henry Burstow that I realised that that was the pipe shop that Mr and Mrs Burstow raised the eleven or twelve kids in. Most incredible. I could tell you a story about what happened to me when I lived there but you'd probably think I was a raving lunatic. For the duration of the time we stayed there with Uncle Fred and Auntie Ruth, I drove everybody mad with a tune, not the song, but a tune - [hums] - 'til everybody in the family said to me. 'Oh! For God's sake, either put some words to it or shut up! ' Now, I privately think that was old Henry trying to tell me something.

I'm never sure how to pronounce it, but that vessel was infested by the teredo worm and it was literally ... well as you know, they tunnel longitudinally and the thing was falling apart and they put a copper bottom on that vessel, over the rotten timbers. And it really was ready to fall apart at one time.

I'm never sure how to pronounce it, but that vessel was infested by the teredo worm and it was literally ... well as you know, they tunnel longitudinally and the thing was falling apart and they put a copper bottom on that vessel, over the rotten timbers. And it really was ready to fall apart at one time.