Rounder 1504/1505

As one who occasionally pokes his nose into the hallowed halls of academe, I find myself assailed by questions of function and meaning. What significance did the carriers of folk tradition place on their songs and music and stories and other artefacts of oral culture? What part did these things play in their lives? How did the people who have pontificated on that tradition over the past couple of centuries interpret the stuff? How do these things affect the way we conceptualise and contextualise what we hear? And how do all these factors affect the kinds of questions we have come to ask? Such ruminations are normally kept apart from private listening, for in modern society we typically compartmentalise music into well defined sections of our lives; except that we also get drenched in it by background sound systems and disco bars and other people's radios. Either way, music nowadays seldom forms an integral part of communal existence. So when I was sent the above release for review, my first reaction was to close the door on the world and just dig the sounds. Well, the sounds are eminently diggable, but the project which resulted in their emergence on disc has questions of function and meaning as pivotal issues.

Before I go any further, let me feed you some raw data, and some familial history. The Hammonses were a migratory family of poor whites, who had lived in various locations in the mountains of the Southern Appalachians for around two centuries, and were noted for fiddling, banjo picking, storytelling and singing. Beginning at Pittsylvania, in the 1770s, their peregrinations took them from the eastern side of Virginia, to Kentucky and then to Tennessee and finally to West Virginia. Always, we are told, their migrations represented a retreat from the advancement of settled communities.![]() 1 I have put that in past tense for the protagonists on this release have regretfully all passed on. I suspect their way of life has passed on also. They first came to the notice of the outside world via agricultural student and old time musician, Dwight Diller, who discovered them in 1968. It appears to have been way of life, rather than music, which drew Diller to the family, for they hadn't played or sung much in nearly four decades.

1 I have put that in past tense for the protagonists on this release have regretfully all passed on. I suspect their way of life has passed on also. They first came to the notice of the outside world via agricultural student and old time musician, Dwight Diller, who discovered them in 1968. It appears to have been way of life, rather than music, which drew Diller to the family, for they hadn't played or sung much in nearly four decades.![]() 2

2

Their home produced entertainment had been terminated partly by changes within the family, but also by the radio and records which carried into the mountains the serpent of hillbilly music, as Maud Karpeles put it.![]() 3 There are those who would accuse Karpeles of narrow mindedness, but we may note that the music of the Hammonses became frozen less than twenty years after she and Sharp had scoured the Southern Appalachians in search of cultural and ethnic purity. This release therefore affords an opportunity to consider the validity of arguments concerning the so called British ancestry of Appalachian folk music.

3 There are those who would accuse Karpeles of narrow mindedness, but we may note that the music of the Hammonses became frozen less than twenty years after she and Sharp had scoured the Southern Appalachians in search of cultural and ethnic purity. This release therefore affords an opportunity to consider the validity of arguments concerning the so called British ancestry of Appalachian folk music.

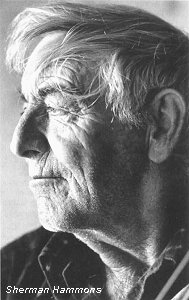

Diller encouraged the Hammonses to start performing again and brought them to the notice of Carl Fleischauer and Alan Jabbour of the Library of Congress. This led Fleischauer and Jabbour to conduct an intensive investigation of the family. It was, to borrow a term from philosophy, a holistic study. That is, rather than concentrate on conventional modes of folklore, they probed every aspect of the Hammonses existence; their songs and stories, their agricultural and house building techniques, their family history, word lore and cuisine; I gather that Maggie, the matriarch of the family, could make a tasty groundhog stew. The study was conducted over a two year period from 1970 to 1972 and the recordings which came out of it yielded three LPs. There was a double header from the Library of Congress, featuring Sherman Hammons on fiddle and banjo, Burl, who likewise played banjo, and Maggie Hammons Parker, who sang. Besides music, all three members could tell a good story. The L of C issue was complemented by a single Rounder disc, called Shaking Down the Acorns, on which the Hammonses received a little help from their friends, Mose Coffman and Lee Hammons. As far as is known, the latter is no relation.

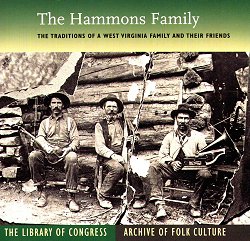

The three LPs are now combined in a single, most elegant piece of hardware. It consists of a double CD, total playing time 134 minutes and 40 tracks, which comes in a slip case together with a 120 page book.  The notes and illustrations of the original issues are left fairly intact and I was particularly taken by the cover photograph, which was taken around the year 1900. It shows three of the Hammonses holding three indispensable items of backwoods life; a rifle, a fiddle and a phonograph. There are detailed notes for each track, plus song and story transcriptions where appropriate. There is a family history and genealogy by Carl Fleischauer, which combines oral testimony with historical records, and there is an introductory essay by Alan Jabbour.

The notes and illustrations of the original issues are left fairly intact and I was particularly taken by the cover photograph, which was taken around the year 1900. It shows three of the Hammonses holding three indispensable items of backwoods life; a rifle, a fiddle and a phonograph. There are detailed notes for each track, plus song and story transcriptions where appropriate. There is a family history and genealogy by Carl Fleischauer, which combines oral testimony with historical records, and there is an introductory essay by Alan Jabbour.

I wish I didn't have to carp at such a lavish production, but I also wish that Jabbour's essay could have been brought up to date. In the process of researching the Hammonses' history Jabbour has reached some fascinating and important, but maddeningly tentative conclusions about the nature of Appalachian music. His words are brief, but too central to the concept of these discs not to need summarising here. He says that the Southern Appalachians, or that part occupied by the Hammonses, was populated by two classes or culture groups. One group consisted of small farmers, descendants of the Scots, Ulster Scots and Germans, who settled the arable river valleys in the eighteenth century, but there is a second and poorer class of migrants who occupied the higher, less fertile ground, and whose roots in America go back further. This latter group are subsistence hunters, trappers, gatherers, gardeners and animal husbanders, and it is with these that the Hammonses belong. In the case of the Hammonses they are also loggers.

For Jabbour the discovery of this migrant class has serious implications in terms of our understanding the origins of Appalachian music. Appalachian music is generally held to be a late eighteenth century British importation, with a few modifications from other groups, mainly the Negro population. Now we find its genesis pushed back by a good half century. The time scale is crucial for two reasons. Firstly, it is all the longer for Appalachian music to develop its own dynamic. Secondly, a revolution appears to have taken place in British folk music of the late eighteenth century, the effect of which has been to obscure our knowledge of what went before.

I am sorry if I've missed the revolution and I must confess myself confused by what he says. I am also confused by his use of the term Britain. Elsewhere, he stretches it to embrace Ireland and I suspect he is doing so here. Ireland is a separate self governing country and many Irish people find it offensive to be identified with the Union of Great Britain. At the time of which we speak, Ireland was politically under the domination of Britain, but it was culturally, socially and, to a large extent, linguistically quite separate. True, the Irish dance tradition was heavily influenced by English models imported by the Protestant ascendancy. However, it was, like the Appalachian tradition, developing a dynamic and a cultural identity of its own.

Regarding the revolution, there was a large increase in printed music sources for country dances in the late eighteenth century and I presume this is what Jabbour means. However, an increase in printed sources suggests an explosion of interest in dancing among the affluent elite, rather than a revolution among the folk. It begs the question, who was playing music off the printed page, and for whom?

I need to object. If the purpose of the study was to understand the culture of the Hammonses in the round, so to speak, why do we feel we have to look for origins? Surely the aim was to understand the music of the Hammonses as an integral part of their way of life, rather than where they got it from? As far as Appalachian music is concerned, the search for origins is traceable back to the door of Cecil Sharp. However, Sharp was merely using a theoretical approach which had far wider applications than folklore and folksong studies, which had been around long before his own era, and which it has taken folklorists a long time to grow out of. I suspect Jabbour may be trying to debunk that approach. If so, I can only agree, for I do not feel that explaining music in terms of where it came from will, on its own, tell us very much.

I am not sure either what to make of the geographical implications of this music, or how it may be compared with the rest of Appalachia. As far as repertoire is concerned their wandering through the backwoods appears to have endowed the family with a distinctive set of tunes, some of which appear unique. One wonders whether titles like Three Forks of Cheat and Cranberry Rock, might reflect landmarks on their wanderings. Of the more common items, Old Joe Clark seems to be lurking about in the tune Muddy Roads, and the ubiquitous Sugar Babe crops up twice. Otherwise, there is only an odd Turkey lurking in the Straw. Old time musicians in search of fresh material could certainly do a lot worse than pick their way through this lot.

However, if migratory existence has affected the tunes they play, I am less clear about its effects on the way that they play them. There is no suggestion from the editors, or from anywhere else I've looked, that their way of playing differs significantly from the rest of West Virginia. This is surprising for we could expect a patchwork of influences encompassing all the places the Hammonses stopped off at. I must confess myself at a disadvantage here, for West Virginia is one part of the Southern Appalachians whose music I have not listened to a great deal.  Whether it is typical of that State or no, the playing on these discs is stamped with its own sound.

Whether it is typical of that State or no, the playing on these discs is stamped with its own sound. ![]() It is less frenetic than Appalachian music generally and it is interesting that Burl Hammons makes extensive use of scordatura, or dissonant tuning. (sound clip - Three Forks of Cheat) This is a trait I have noticed among other Appalachian fiddlers. It was also a trait among seventeenth and eighteenth century classical violinists of the Viennese school, and we may chance to wonder if it came into the mountains with the same German settlers who introduced the Appalachian dulcimer to the region. Folklorists are great cataloguers and classifiers and, although I feel that indices based on aural impressions alone are of limited facility, I am surprised that more has not been done to classify American playing styles on a regional basis. In any case, a degree of confusion reigns, since the book claims scordatura as a trait of Central West Virginia. On the other hand, Burman-Hall's typology of Southern American fiddle styles identifies it as a part of what she calls a Blue Ridge style. The geographic boundaries of this style are not made very clear, but she appears to be referring to the land mass east of the Blue Ridge mountains, which separate Virginia from North Carolina, rather than to the Blue Ridge proper.

It is less frenetic than Appalachian music generally and it is interesting that Burl Hammons makes extensive use of scordatura, or dissonant tuning. (sound clip - Three Forks of Cheat) This is a trait I have noticed among other Appalachian fiddlers. It was also a trait among seventeenth and eighteenth century classical violinists of the Viennese school, and we may chance to wonder if it came into the mountains with the same German settlers who introduced the Appalachian dulcimer to the region. Folklorists are great cataloguers and classifiers and, although I feel that indices based on aural impressions alone are of limited facility, I am surprised that more has not been done to classify American playing styles on a regional basis. In any case, a degree of confusion reigns, since the book claims scordatura as a trait of Central West Virginia. On the other hand, Burman-Hall's typology of Southern American fiddle styles identifies it as a part of what she calls a Blue Ridge style. The geographic boundaries of this style are not made very clear, but she appears to be referring to the land mass east of the Blue Ridge mountains, which separate Virginia from North Carolina, rather than to the Blue Ridge proper.![]() 4 I cannot act as arbiter.

4 I cannot act as arbiter.

However, the geographical delineation reminded me that shortly after these recordings were made, Tom Carter and Blanton Owen carried out a survey of playing styles in the Blue Ridge, which showed the area broken down into five sub-regions.![]() 5 Of these, the musicians they chose as representatives of the area surrounding Galax, Virginia, sound to my ears, the most archaic and the least 'Appalachian'.

5 Of these, the musicians they chose as representatives of the area surrounding Galax, Virginia, sound to my ears, the most archaic and the least 'Appalachian'. ![]() In fact they sound a bit like the Hammonses. (sound clip - Fanny Hill. John Rector, Galax. Rec 31/1/74.)

In fact they sound a bit like the Hammonses. (sound clip - Fanny Hill. John Rector, Galax. Rec 31/1/74.)![]() 6 This is not a hobby horse I wish to ride very hard. So far as I know, the Hammonses were never in Galax and I am not trying to infer any direct influence. Nor do I think it necessarily the case that the Hammonses - insulated from outside communities - and Galax musicians - buried deep in the Blue Ridge - are fellow custodians of an archaic music which survived both the Atlantic passage and the passage of time. What I do wish to do is throw doubt on the idea that regional typologies and/or 'origin gazing' can tell us very much.

6 This is not a hobby horse I wish to ride very hard. So far as I know, the Hammonses were never in Galax and I am not trying to infer any direct influence. Nor do I think it necessarily the case that the Hammonses - insulated from outside communities - and Galax musicians - buried deep in the Blue Ridge - are fellow custodians of an archaic music which survived both the Atlantic passage and the passage of time. What I do wish to do is throw doubt on the idea that regional typologies and/or 'origin gazing' can tell us very much.

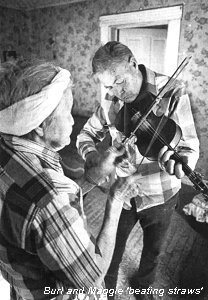

The discs are arranged segmentally, so that Burl gets the first 18 tracks of disc 1, while Sherman gets the rest, with most of disc 2 being given over to Maggie. The set is rounded off with two tunes from Lee Hammons and three from Mose Coffman. I would have preferred it had the tracks been intermixed, to give the production more of a family feel. Incidentally, with the exception of one track, Jimmy Johnson, where Maggie beats an accompaniment to Burl's fiddle, these are all solos. I wondered whether this was just the way the L of C had recorded the family, but it isn't. The Hammonses appear to be an exception to the rule which says, 'The family that plays together stays together'.

For seekers after virtuosoity, these discs may prove somewhat limiting. This is down home, front porch music, as plain and unpretentious as one of Maggie Parker's groundhog stews. However, to look for pyrotechnics in this sort of music is to misunderstand it. Folk music is not about virtuosity, it is about satisfying a fundamental human requirement. I believe the need for artistic expression is inherent to our species and that, for the vast majority of human beings, it has been stifled by technology, progress, mass society, and a belief that art is for the gifted few. I do not intend to rehearse the arguments put forward by the late John Blacking, except to say that he regarded the human race as innately musical; that the need to say who we are via music is in our genes.![]() 7

7  Blacking confined his argument to music, but I believe we can expand it to include dance and storytelling and all the other arts which make up folk tradition.

Blacking confined his argument to music, but I believe we can expand it to include dance and storytelling and all the other arts which make up folk tradition.

Recognition of this need may help explain the custom of 'beating the straws'. This is the habit of using a pair of straws, sticks or knitting needles to hammer out a rhythm against the strings on the neck of a fiddle, while the fiddler plays the melody. It is not a practice I have come across with British or Irish fiddlers and it does not seem all that common among white American musicians. There are however numerous references to the habit in plantation literature.![]() 8 From this I'd deduce that the practice developed among slaves, not as an African survival, although African mouth bow players do sometimes produce a melody by beating the string of the mouthbow.

8 From this I'd deduce that the practice developed among slaves, not as an African survival, although African mouth bow players do sometimes produce a melody by beating the string of the mouthbow.![]() 9 Rather, I feel that it arose as a response to restrictions in musical usage. That is, when the planters suppressed African instruments they denied the slaves cultural rhythmic expression. The need to express rhythm found an outlet in a number of different ways. It surfaced as syncopation and swing and as body percussion and straw beating.

9 Rather, I feel that it arose as a response to restrictions in musical usage. That is, when the planters suppressed African instruments they denied the slaves cultural rhythmic expression. The need to express rhythm found an outlet in a number of different ways. It surfaced as syncopation and swing and as body percussion and straw beating.

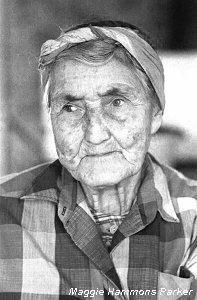

Maggie is much more than just a beater of straws. For me she is the star of the show. True, her voice sounds impaired with age, and there are some startling gear shifts as she grapples with the high notes.  Yet enough style and passion have survived to show that she must have once been a devastating singer. Alan Lomax has commented that the two finest singers he heard in America were Aunt Molly Jackson and Texas Gladden.

Yet enough style and passion have survived to show that she must have once been a devastating singer. Alan Lomax has commented that the two finest singers he heard in America were Aunt Molly Jackson and Texas Gladden.![]() 10 Had the Library of Congress recorded Maggie Hammons Parker in the 30s, he would surely have added her name to the list.

10 Had the Library of Congress recorded Maggie Hammons Parker in the 30s, he would surely have added her name to the list.

The songs are almost as interesting as the singer. She offers ten here, plus a couple of tales and one or two riddles. Yet I gather her song repertoire ran to several hundred items. Dare we hope that some future publication will feature more of this fascinating lady? Of the present selection, there is run of the mill Appalachia in the forms of Young Hunting, Little Omie and The Lonesome Pines, ![]() but there is also a rare version of Hind Horn, a delightful Marrowbones and what I consider the gem of the whole set; Ireland's Green Shore. (sound clip). This beautiful composition is Irish, not British as the book has it. It is a nineteenth century broadside ballad, and an English language crossover from an earlier Gaelic political tradition of aisling or vision poetry. In most versions of the song, indeed in most songs of the aisling form, the poet dreams of a mournfully handsome woman who reveals herself to him as the soul of Ireland, or the daughter of some legendary Irish personage, and the two of them lament the sorrows of Erin. Maggie's version is shorn of the political references and it emerges as a straightforward love song. Nevertheless, the song appears in many American collections and it may seem strange that something bemoaning the sufferings of Ireland should have taken such a strong root in America. However, at least one version exists under the title Dixie's Green Shore and that may provide us with a clue.

but there is also a rare version of Hind Horn, a delightful Marrowbones and what I consider the gem of the whole set; Ireland's Green Shore. (sound clip). This beautiful composition is Irish, not British as the book has it. It is a nineteenth century broadside ballad, and an English language crossover from an earlier Gaelic political tradition of aisling or vision poetry. In most versions of the song, indeed in most songs of the aisling form, the poet dreams of a mournfully handsome woman who reveals herself to him as the soul of Ireland, or the daughter of some legendary Irish personage, and the two of them lament the sorrows of Erin. Maggie's version is shorn of the political references and it emerges as a straightforward love song. Nevertheless, the song appears in many American collections and it may seem strange that something bemoaning the sufferings of Ireland should have taken such a strong root in America. However, at least one version exists under the title Dixie's Green Shore and that may provide us with a clue.![]() 11 Perhaps, in the post bellum South, with a broken economy, an army of occupation, and a legacy of carpetbaggers, the condition of the poor Whites was not so very different from that of the downtrodden Irish. As a bonus, Maggie sings the song to a variant of the handsome Gaelic air, Bean an Leanna, rather than Rosin a Bow, with which it is sometimes associated. Maggie Parker may have been a purveyor of handsome airs.

11 Perhaps, in the post bellum South, with a broken economy, an army of occupation, and a legacy of carpetbaggers, the condition of the poor Whites was not so very different from that of the downtrodden Irish. As a bonus, Maggie sings the song to a variant of the handsome Gaelic air, Bean an Leanna, rather than Rosin a Bow, with which it is sometimes associated. Maggie Parker may have been a purveyor of handsome airs. ![]() The melody of Ireland's Green Shore has a much greater range than is usual in America and its width is echoed in her tune for The Lonesome Pines (sound clip). The latter is part of the complex of melodies which we associate with this song, but it is altogether bigger and more handsome than most of its associates, and it goes off in some very interesting directions.

The melody of Ireland's Green Shore has a much greater range than is usual in America and its width is echoed in her tune for The Lonesome Pines (sound clip). The latter is part of the complex of melodies which we associate with this song, but it is altogether bigger and more handsome than most of its associates, and it goes off in some very interesting directions.

Back to the roots. My gut feeling is that white American traditional music is traceable to English and Scottish country dance of the early eighteenth century and before, but only in an attenuated form. I suspect that, in the times of which we speak, few musicians made it to America, that the few who did passed the music onto the Negro slave population,![]() 12

12  and that it was the slaves who were the initial catalyst in moulding what we now regard as the traditional music of White America. To reach that conclusion a little deductive reasoning is required.

and that it was the slaves who were the initial catalyst in moulding what we now regard as the traditional music of White America. To reach that conclusion a little deductive reasoning is required.

In colonial America, the provision of music was a servant's task, rather than a pastime of masters. This echoes contemporary music making practices on this side of the Atlantic. Reg Hall's estimable study of Irish dance music shows that, in pre-famine Ireland, the tradition was far from being the mass popular phenomenon we know today. In fact it was almost exclusively in the hands of a small number of professional artisans, most of whom were either crippled or blind.![]() 13 From this Reg concludes that Irish musicians can have had only a minimal effect upon American music, for few would have been able to travel to America.

13 From this Reg concludes that Irish musicians can have had only a minimal effect upon American music, for few would have been able to travel to America.![]() 14 I think he's right and I appear not to be the only one who hears more English influence than Irish in this music. Samuel P Bayard apparently once claimed that American fiddle tunes are closer to the straightforward English way of playing than to the more ornate Gaelic tradition.

14 I think he's right and I appear not to be the only one who hears more English influence than Irish in this music. Samuel P Bayard apparently once claimed that American fiddle tunes are closer to the straightforward English way of playing than to the more ornate Gaelic tradition.![]() 15 I have not had the opportunity to check Bayard's words and I do not know whether he based them on anything more than that folkloristic standby, aural evidence. I can only observe that, if, among the wide variety of Irish fiddle techniques, such a thing as a Gaelic style of playing exists I have yet to unearth it. The trouble with aural impressions is that they are subjective; we hear in music the sounds and influences that we want to hear. But if we cannot trust the aural record, does the historical record say or suggest that English settlers, or the Scots, or Ulster Scots were of greater consequence than the Irish in the shaping of American folk music?

15 I have not had the opportunity to check Bayard's words and I do not know whether he based them on anything more than that folkloristic standby, aural evidence. I can only observe that, if, among the wide variety of Irish fiddle techniques, such a thing as a Gaelic style of playing exists I have yet to unearth it. The trouble with aural impressions is that they are subjective; we hear in music the sounds and influences that we want to hear. But if we cannot trust the aural record, does the historical record say or suggest that English settlers, or the Scots, or Ulster Scots were of greater consequence than the Irish in the shaping of American folk music?

My knowledge of English and Scottish country dance is slender to put it mildly.![]() 16 However, the tradition of artisan produced music in Ireland was supported, if not actually initiated, by a Protestant ascendancy who had acquired their lands and titles as the result of Cromwellian subjugation of that country. It comes as no surprise therefore to learn that similar systems for the provision of dancing prevailed in England and Scotland.

16 However, the tradition of artisan produced music in Ireland was supported, if not actually initiated, by a Protestant ascendancy who had acquired their lands and titles as the result of Cromwellian subjugation of that country. It comes as no surprise therefore to learn that similar systems for the provision of dancing prevailed in England and Scotland.![]() 17 Reg's rationale for this tradition of professional Irish musicians comes down to the backward economy of Ireland and the fact that, although the lower orders were glad to join the dance, they were too poor to buy instruments. Hence they were unable to make music for themselves. This situation changed after the potato famine of the mid 1840s, when death and emigration resulted in the massive depopulation of a previously overcrowded Irish countryside. Depopulation led to a rise in affluence for the ones who were left, which meant that for the first time Irish country people could afford the luxury of home produced music. The argument is compatible with the economic history of Ireland.

17 Reg's rationale for this tradition of professional Irish musicians comes down to the backward economy of Ireland and the fact that, although the lower orders were glad to join the dance, they were too poor to buy instruments. Hence they were unable to make music for themselves. This situation changed after the potato famine of the mid 1840s, when death and emigration resulted in the massive depopulation of a previously overcrowded Irish countryside. Depopulation led to a rise in affluence for the ones who were left, which meant that for the first time Irish country people could afford the luxury of home produced music. The argument is compatible with the economic history of Ireland.![]() 18 But if, in Ireland, poverty and patronage kept the music in the hands of a small number of professionals, I find it hard to believe that the situation would have been hugely different in contemporary England or Scotland. I doubt also that a significant proportion of the musicians who did exist would have found their way to America.

18 But if, in Ireland, poverty and patronage kept the music in the hands of a small number of professionals, I find it hard to believe that the situation would have been hugely different in contemporary England or Scotland. I doubt also that a significant proportion of the musicians who did exist would have found their way to America.

Planters, both of Ireland and America, attempted to establish their new social position by emulating customs of the elite which they had been aware of at home. Country dance was a pastime of that elite, and it was an important status marker for the planters. In both countries the desire to show off status appears to have outstripped musical resources. In Ireland the problem was solved by setting disabled youths to a musical apprenticeship. In early colonial America the most likely musical resource would appear to have been such European indentured servants as could play instruments. However, servants were recruited for their capacity to work rather than for their capacity to play music and the indentured servant system does not seem a likely route of entry to America for professional musicians. Either they came in by some other route, or they did not come in significant numbers.

In any event, by the late seventeenth century, indenture was on the way out and was becoming displaced by the much larger slave trade. A number of factors affected the decline, but Kolchin's study of slavery demonstrates that, by this time, the numbers of servants willing to sell themselves into indenture had fallen off badly. Hence, planters felt the need to engage in the slave trade.![]() 19 We may observe also that the American economy was expanding geographically as the frontier was pushed back. That means a greater number of planters. That means a greater demand for musicians. The slave trade was a Godsend to expatriate country dancers. As the extensive documentation presented by Dena Epstein shows, planters were quick to discover what they thought to be traits of innate musicality in their African charges. To quote John Blacking, "In primitive societies, everybody sings. In agrarian societies, most people sing. In modern societies, hardly anybody sings".

19 We may observe also that the American economy was expanding geographically as the frontier was pushed back. That means a greater number of planters. That means a greater demand for musicians. The slave trade was a Godsend to expatriate country dancers. As the extensive documentation presented by Dena Epstein shows, planters were quick to discover what they thought to be traits of innate musicality in their African charges. To quote John Blacking, "In primitive societies, everybody sings. In agrarian societies, most people sing. In modern societies, hardly anybody sings".![]() 20

20

Whether their owners were misled or no, slave musicians became the major source of plantation dance music, and its earliest and most crucial mediating force. They did not simply reproduce European dance music as they had been taught it. Rather they refashioned the material over time into their own image.![]() 21 That image was neither African, nor European, nor, strictly speaking, was it even American. It drew on elements from all three continents, but it represented the acculturative processes of slavery; the adaptation of various cultural elements to the peculiar social conditions the slaves found in the New World.

21 That image was neither African, nor European, nor, strictly speaking, was it even American. It drew on elements from all three continents, but it represented the acculturative processes of slavery; the adaptation of various cultural elements to the peculiar social conditions the slaves found in the New World.![]() 22 Subsequent generations of European immigrants doubtless brought their own musics to the melting pot of the American South, but these would have been additional to the ingredients already in place.

22 Subsequent generations of European immigrants doubtless brought their own musics to the melting pot of the American South, but these would have been additional to the ingredients already in place.

If we cannot assign a British or Irish pedigree to the music can we do any better with the songs? So many unanswered questions are thrown up by this project. The migratory existence of families like the Hammonses presumably arose out of resource depletion; the extermination of game perhaps, or changes in the economy of logging. But why did they move over such huge distances and why did they always stick to the higher ground? Why, in a land where Alan Lomax claims that fifty per cent of the national repertoire is religious, do the Hammonses have so few religious songs?![]() 23 Why did this family, locally popular as entertainers, not try and emulate the commercial success of other kinship groups, such as the Stonemans or Fiddlin' John Carson and Moonshine Kate? Were they too poor to afford transportation to the recording units? Were they too estranged socially and geographically from the urban centres where the units were set up, and where they would have found audiences willing to pay them for their talents? A picture begins to emerge of a family scrabbling about in a back country so remote from the rest of humanity as to remain untouched by progress, or by religious awakenings, or by any of the normal machinations of plain folk America. Country music specialists, Bill Malone among them, have been quick to remind us that the Southern Appalachians were not quite the safe haven of "Old English" songs and ballads, which the settlement schools and Olive Dame Campbell and Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles claimed.

23 Why did this family, locally popular as entertainers, not try and emulate the commercial success of other kinship groups, such as the Stonemans or Fiddlin' John Carson and Moonshine Kate? Were they too poor to afford transportation to the recording units? Were they too estranged socially and geographically from the urban centres where the units were set up, and where they would have found audiences willing to pay them for their talents? A picture begins to emerge of a family scrabbling about in a back country so remote from the rest of humanity as to remain untouched by progress, or by religious awakenings, or by any of the normal machinations of plain folk America. Country music specialists, Bill Malone among them, have been quick to remind us that the Southern Appalachians were not quite the safe haven of "Old English" songs and ballads, which the settlement schools and Olive Dame Campbell and Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles claimed.![]() 24 The remoteness of Appalachia, Malone tells us, had long been penetrated by sheet music and phonographs and by vaudeville and music hall and medicine shows and blackface minstrelsy. Yet these things would have worked their way into the region first through the urban settlements, then through the arable valleys, before reaching the higher backwoods little and late if at all.

24 The remoteness of Appalachia, Malone tells us, had long been penetrated by sheet music and phonographs and by vaudeville and music hall and medicine shows and blackface minstrelsy. Yet these things would have worked their way into the region first through the urban settlements, then through the arable valleys, before reaching the higher backwoods little and late if at all.

For the moment let's leave the photographic evidence on one side. Let's forget that the Hammonses had access to a phonograph, and presumably a camera, at least a decade before anyone might have asked them whether they had any folk songs, and a quarter century before their kind of music began to appear on record.![]() 25 Do any factors in their way of life - remoteness, isolation, pre-literacy, or whatever - provide a justification for Sharp's belief in a pure English Appalachian folk tradition? Much recent criticism of Sharp has been more in the nature of character assassination than serious scholarship and I have no wish to fuel the conflagration. I feel that Sharp made an invaluable contribution to folk song scholarship, which needs to be understood and assessed not just against the march of progress and changing intellectual ideas, but also against the intellectual climate of his own time.

25 Do any factors in their way of life - remoteness, isolation, pre-literacy, or whatever - provide a justification for Sharp's belief in a pure English Appalachian folk tradition? Much recent criticism of Sharp has been more in the nature of character assassination than serious scholarship and I have no wish to fuel the conflagration. I feel that Sharp made an invaluable contribution to folk song scholarship, which needs to be understood and assessed not just against the march of progress and changing intellectual ideas, but also against the intellectual climate of his own time.![]() 26 Nevertheless, I feel that to call Appalachian folk music English is to grossly distort the evidence. Even Sharp was aware that Southern Appalachian melodies do not sound like the ones he had been used to collecting in Southern England. Correspondence with J C Campbell, the husband of Olive Dame Campbell, shows that he acknowledged the presence of a large number of Scots and Ulster Scots descendants among the Appalachian population and that he was aware of their musical influence.

26 Nevertheless, I feel that to call Appalachian folk music English is to grossly distort the evidence. Even Sharp was aware that Southern Appalachian melodies do not sound like the ones he had been used to collecting in Southern England. Correspondence with J C Campbell, the husband of Olive Dame Campbell, shows that he acknowledged the presence of a large number of Scots and Ulster Scots descendants among the Appalachian population and that he was aware of their musical influence.![]() 27 In his major work on the subject Sharp, in pointing to the existence of a large number of gapped scales in Appalachia, offers two possible explanations.

27 In his major work on the subject Sharp, in pointing to the existence of a large number of gapped scales in Appalachia, offers two possible explanations.![]() 28 Firstly he suggests that they may indicate a Northern English or Lowland Scots ancestry. This apparently does not undermine his theory of Engishness because, Sharp claims, England and Scotland are all one culture area. He also toys with the possibility that the people and the melodies are the equivalents of living fossils, isolation having kept both in states of suspended evolution since the region was opened up. As Maud Karpeles, talking about the melodies, put it, 'Whether they have suffered a sea change, or whether they represent English folk music of an earlier period is open to argument.'

28 Firstly he suggests that they may indicate a Northern English or Lowland Scots ancestry. This apparently does not undermine his theory of Engishness because, Sharp claims, England and Scotland are all one culture area. He also toys with the possibility that the people and the melodies are the equivalents of living fossils, isolation having kept both in states of suspended evolution since the region was opened up. As Maud Karpeles, talking about the melodies, put it, 'Whether they have suffered a sea change, or whether they represent English folk music of an earlier period is open to argument.'![]() 29

29

The first of these pronouncements makes no more sense than does lumping Ireland in with Britain. The second is a negation of Sharp's theories on the development of folk melody. Sharp was an evolutionist who applied the theories of Charles Darwin to folk music. He believed that the melodies acquired their folk-like characters, and their handsome shapes, via the selective processes of the community, just as living species acquired their animal characteristics from the selective processes of nature.![]() 30 If he was correct, the music of the Southern Appalachians would not have stood still. Like the famous turtles of the Galapagos Islands, songs and melodies would have taken on distinctive shapes to match the local conditions. That is pretty much what happened.

30 If he was correct, the music of the Southern Appalachians would not have stood still. Like the famous turtles of the Galapagos Islands, songs and melodies would have taken on distinctive shapes to match the local conditions. That is pretty much what happened.

Besides the Scots there were other population groups, Negro and German, which Sharp and Karpeles don't mention. The effects of these on the local music are impossible to quantify, but they must be in there somewhere. What is at issue though is not where the stuff came from, but how songs and melodies and repertoires and performance styles were shaped and moulded by the frugality of life on the American frontier and by its harshness and uncertainties. Examination of Appalachian song bears this out. There are few of the lyrical conventions which preoccupied the writers of English folk songs, and there is far more wrongdoing and violence and murder. You won't find many sweet maids in the month of May, but you'll find a lot of jealousy and shame and a lot of "false true lovers". If the harshness of life is mirrored in the texts it is also mirrored in the melodies which supported them, and in the harsh way in which Southern mountaineers frequently sang. Like the slaves of plantation America, the settlers of the Appalachian mountains took pre-existing cultural forms and changed and moulded them to suit new conditions. Folksongs of the Southern Appalachians are not English or British, or even American. They are Southern Appalachian.

The world of folklore studies has changed beyond all recognition since the days when Sharp and Karpeles trekked these mountains. In Sharp's time all folkloristic enquiry ended up as a trek for origins.![]() 31 In some cases the motives were anthropological; the tracing of Western man's currently elevated state back to a simpler brutish existence. In some cases they were antiquarian, and in Sharp's case they were nationalistic; he sought to invest the English people with a corporate national musical identity. Whatever their motivation, such quests invariably ran into problems of accuracy and verification and empiricism and utilisation. Regarding folklore elements as survivals of a former savage existence does not tell us why they survived into a more urbane landscape. Labelling a musical culture as British expatriate doesn't tell us why it survived in America, or in what ways it might have changed, or why it changed. For that we need to understand folklore as part of the lives of the people who carried it. We need to appreciate folklore as a mechanism for coping with the exigencies of life.

31 In some cases the motives were anthropological; the tracing of Western man's currently elevated state back to a simpler brutish existence. In some cases they were antiquarian, and in Sharp's case they were nationalistic; he sought to invest the English people with a corporate national musical identity. Whatever their motivation, such quests invariably ran into problems of accuracy and verification and empiricism and utilisation. Regarding folklore elements as survivals of a former savage existence does not tell us why they survived into a more urbane landscape. Labelling a musical culture as British expatriate doesn't tell us why it survived in America, or in what ways it might have changed, or why it changed. For that we need to understand folklore as part of the lives of the people who carried it. We need to appreciate folklore as a mechanism for coping with the exigencies of life.

Which brings me to the stories, arguably the most important element in this release. Here, I need to pause and qualify the use of the term family. I suspect that in the old days the Hammons family would have taken the form of an extended kinship network, with several different branches loosely hung together. In the Appalachian wilderness such a network would have had serious problems in terms of stability and integration and I think this is the reason why the stories existed. They are not the traditional wonder tales or hausmarchen which folklorists used to pore over for evidence of latent savagery or linguistic diffusion. Instead the Hammonses relate various incidents stretching back to the time of their arrival on the frontier, and which invoke memories of civil war and feuds and fights with witches and threats from Indians and wild animals. These are episodes in the family chronology which have stuck in the collective mind, so that they constitute a patchwork history in the form of a discontinuous series of nodes. Where, in the field of intellectual enquiry, would we situate such a narrative? It is of interest to the Hammonses, but is it of interest to historians? Oral history has an uneven reputation because of difficulties of verification and faulty memory. Here we have an oral history which is subject not only to the vagaries of the individual, but to the vagaries of transmission. The stories moreover present neither a continuous record, or a coherent one. However, to look for continuity or coherence or accuracy is to miss the point. Firstly, if Jabbour and Fleischauer were able to produce a historical account by combining oral and written sources, then the oral record must count for something. Secondly, history is not just about the objective chronicling of verifiable fact. It is, or ought to be, also about chronicling impressions; about the way people felt and about the lives they led and about how the forces of history shaped and moulded the world around them. Finally, one of the functions of history is to invest its inheritors with a sense of unity and a common identity. That need is prevalent in all societies, whether literate or pre-literate, and it is a need which the Hammons family history achieves.

Mody Boatright was one of the few folklorists who paid any attention to these family sagas as he called them.![]() 32 Boatright saw them as folklore in the form of sagas because of the way they are constructed and because of their modes of transmission and ownership. They are sagas because they are built from clusters of incidents which form a cogent whole without forming a continuous narrative. They are folklore because they are transmitted via the oral process, and are subject to collective selection and alteration so that they form part of the collective consciousness of the group; part of the group culture. No segment of the group has any special rights to the stories, or any special control over their development. They are owned by the group and each member has access to them and takes a part in shaping them by virtue of his or her membership.

32 Boatright saw them as folklore in the form of sagas because of the way they are constructed and because of their modes of transmission and ownership. They are sagas because they are built from clusters of incidents which form a cogent whole without forming a continuous narrative. They are folklore because they are transmitted via the oral process, and are subject to collective selection and alteration so that they form part of the collective consciousness of the group; part of the group culture. No segment of the group has any special rights to the stories, or any special control over their development. They are owned by the group and each member has access to them and takes a part in shaping them by virtue of his or her membership.

From Boatright's account, family sagas seem to have been an endemic feature of frontier life and it is strange that they do not appear in other family settings. This may be because no-one has asked. My feeling is though, that investigation of the lore of other kinship networks would reveal collections of disparate family traditions, rather than the complex of events to which we could apply the term saga.

Boatright's analysis does not penetrate much beyond his identification of the sagas as folklore. However, he opens up two avenues of thought. Firstly, there is his claim that the sagas took shape in the collective mind because they relate to incidents which group members find appealing and unusual. Looking at the Hammonses saga it seems to be made up of occurrences which have, at one time or another threatened the well-being of the family. Secondly, the notion of group ownership affords a clue as to why the sagas existed, and why I think they would be peculiar to families like the Hammonses.

Ben Botkin once observed that, in a purely oral culture, everything is folklore.![]() 33 What he meant was that, if a society is entirely preliterate, then oral tradition is the sole agent of cultural transmission. Therefore, everything has to be held in the collective memory of the group. Therefore, everything is folklore and folklore is the sole agent for the fulfilment of social need. Botkin's reasoning sounds a bit like the doctrine of original sin, but it forces us to reconsider our terminology and to look at folklore in terms of its social significance. Not so long ago the "knowledge of the folk" was thought of as a sort of shopping list of savage survivals, confined chiefly to ignorant peasants in isolated communities. We now consider that, in one form or another, it is endemic to all human society. That is because there has been a shift of emphasis, from considering folklore in terms of its constituent materials, to considering it as popular culture generated autonomously from within the social group.

33 What he meant was that, if a society is entirely preliterate, then oral tradition is the sole agent of cultural transmission. Therefore, everything has to be held in the collective memory of the group. Therefore, everything is folklore and folklore is the sole agent for the fulfilment of social need. Botkin's reasoning sounds a bit like the doctrine of original sin, but it forces us to reconsider our terminology and to look at folklore in terms of its social significance. Not so long ago the "knowledge of the folk" was thought of as a sort of shopping list of savage survivals, confined chiefly to ignorant peasants in isolated communities. We now consider that, in one form or another, it is endemic to all human society. That is because there has been a shift of emphasis, from considering folklore in terms of its constituent materials, to considering it as popular culture generated autonomously from within the social group.![]() 34 In the kind of society envisaged by Botkin, folklore meets all the functions of social life. Therefore it is synonymous with "that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society", as E B Tylor once defined social culture.

34 In the kind of society envisaged by Botkin, folklore meets all the functions of social life. Therefore it is synonymous with "that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society", as E B Tylor once defined social culture.![]() 35 However, such a society can only exist at the very simplest level, with a complete absence of specialism or a division of labour. In societies of any complexity two things happen. Firstly, the functions of folklore become distributed among various social groups within the community at large. Secondly, folklore itself becomes marginalised. Its functions become increasingly supplemented and displaced by specialist institutions of the wider social culture.

35 However, such a society can only exist at the very simplest level, with a complete absence of specialism or a division of labour. In societies of any complexity two things happen. Firstly, the functions of folklore become distributed among various social groups within the community at large. Secondly, folklore itself becomes marginalised. Its functions become increasingly supplemented and displaced by specialist institutions of the wider social culture.![]() 36

36

Families like the Hammonses come very close to emulating this model of Botkin's. They were self-sustaining social units, through whose resources practically every human need had to be met. True, the photographic evidence indicates that the Hammonses were to some extent part of a monetary economy. Their clothes look store bought, so do their musical instruments and house furniture and they seem to have raised money for these things by their logging activities. But interaction with the monetary world formed only a small part of their total economic activity. True also that, like agrarian peoples generally, backwoods Americans shared their labour in the fulfilment of one another's tasks. When corn wanted shucking, the neighbours would help out at shucking it. When a barn wanted building, the neighbours would help to build it. Yet the hand to mouth existence of the Hammonses suggests that they would not have had much corn to shuck, or much need to build space to store it. They may not therefore have had the same need for neighbours as people farther down the valleys. If so, they would have had even greater need of the family. In the remote American backwoods, take the family away and there is nothing between the individual and the wilderness. It follows then that there was an extraordinary need, over and above normal familial and communal ties, for such a unit to stay in existence. Other social units in other parts of the world can break up and fall apart and the individual members can be absorbed into new ones. Where do the members go if the backwoods family gets broken up?

I'm suggesting therefore, that these stories existed as a means of preserving family stability and identity. In a migratory existence, across an uncertain wilderness populated by Cherokee Indians and hostile animals, the saga was the means of integrating and stabilising and identifying the family and its relationships; the family which says together stays together. The family saga identified the family as a corporate entity and gave the members a corporate identity.

This explains why the Hammonses saga only goes back as far as their arrival on the frontier. They are not a self sustaining social unit before that point. It also explains why I think other families would possess traditions rather than sagas. The need for a corporate identity is a universal fact of family life and every family finds an expression of identity via its kinship lore, but seldom would we find the need quite so pressing as here.

The issues I have raised are not idle ones. Folklore is an integral part of a cultural whole which cannot be understood as a collection of individual elements in isolation from the rest of culture. That is something for which the academic world still has to develop an adequate theoretical framework. Come to that, the academic world has yet to develop an adequate framework with which to apprehend the theories of Cecil Sharp. Among the less cerebrally committed, casual imbibing of Sharp's theories, and those of other evolutionary folklorists, has led to a folk revival ideology which is both chauvinistic and antiquarian. Folklore is not about old English maypoles and morris bells, or about old English Appalachia. It is that part of our culture which we as ordinary people can call our own. Digging the sounds on this release would be a small but worthwhile step in realising that assertion. Understanding them as part of people's lives would be a much bigger one.

Fred McCormick - 20.9.98

Article MT023