In a paper on the song John Barleycorn in 2004 I traced the origin of the song from precursors

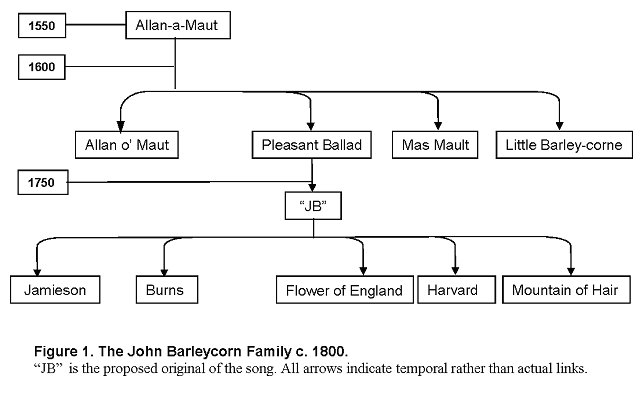

In a paper on the song John Barleycorn in 2004 I traced the origin of the song from precursors![]() 1. This established that the song we have sung in the current revival belongs to a family of songs on the same theme, and whereas the concept of Barley as a person dated back to the 16th century, it took a single event of great inspiration to create the character 'Sir John Barleycorn' in the early 17th century, and later another act of creation which resulted in the modern song, sometime about the mid 18th century. That song has stood the test of time over 250 years by proliferation of both text and tunes to make it one of the most popular folk songs in the English speaking world, the vast majority of which were found in England. As an ex-geneticist, I naturally draw parallels between the development of organisms and songs, and the study of John Barleycorn certainly was a great stimulus in this regard. However, much of the material I wrote at that time was considered too 'speculative' for Folk Music Journal. Whilst respecting the scholars' opinion, I did not agree with it, and having looked at it again, I thought it might be timely to publish it elsewhere, and I hope readers will agree. Let us first look at previous thoughts about evolutionism and folk song.

1. This established that the song we have sung in the current revival belongs to a family of songs on the same theme, and whereas the concept of Barley as a person dated back to the 16th century, it took a single event of great inspiration to create the character 'Sir John Barleycorn' in the early 17th century, and later another act of creation which resulted in the modern song, sometime about the mid 18th century. That song has stood the test of time over 250 years by proliferation of both text and tunes to make it one of the most popular folk songs in the English speaking world, the vast majority of which were found in England. As an ex-geneticist, I naturally draw parallels between the development of organisms and songs, and the study of John Barleycorn certainly was a great stimulus in this regard. However, much of the material I wrote at that time was considered too 'speculative' for Folk Music Journal. Whilst respecting the scholars' opinion, I did not agree with it, and having looked at it again, I thought it might be timely to publish it elsewhere, and I hope readers will agree. Let us first look at previous thoughts about evolutionism and folk song.

There are three essential features of Darwinian evolution, viz. continuity, variation, and selection. In living organisms, the first is provided by reproduction, the second by random mutation, and the third by 'survival of the fittest'. In traditional song, continuity is provided by the social performance of a song over a long period of time, perhaps hundreds of years. In other words, the song is a success, it survives. It is unfortunate that Sharp used continuity differently, to mean 'invariance'![]() 5, and more recent scholarship has put this right by using the word stability. Thus Russell makes the point that 'stability' and 'change' are more appropriate than 'continuity' and 'variation', since the latter terms imply 'wider relationships which cannot be proven.'

5, and more recent scholarship has put this right by using the word stability. Thus Russell makes the point that 'stability' and 'change' are more appropriate than 'continuity' and 'variation', since the latter terms imply 'wider relationships which cannot be proven.'![]() 6 In other words, there is no force at work, driving the songs in a particular direction, simply that we can get both stability and change at different points in time and place.

6 In other words, there is no force at work, driving the songs in a particular direction, simply that we can get both stability and change at different points in time and place.

Sharp's analysis of variation led to his assertion, by the use of a very few examples, that:

The analogy with species evolution starts to get limited at this point for the simple and obvious reason that whereas each song needs an original creator, living organisms do not. The chemical changes (mutations) which cause variation in living organisms are entirely random, and can be beneficial, neutral, or harmful in their effect. Natural selection then chooses between these. There is no consciousness at work here, either by a God or by the organisms themselves. In folksong, there are both accidental (random) changes and conscious (semi-random?) changes. Whilst it is obvious that in a purely oral culture, changes will accrue due to forgetfulness by the singers, it is equally clear that they have made alterations to the songs they had inherited for reasons of personal preference, artistic judgement, bringing an older song into a contemporary and/or local context, or in an effort to explain an otherwise incomprehensible phrase. Thus the variation by the singer has been twofold, accidental and conscious. The same is true of the other people who have been involved in a song's transmission through history. Collectors and editors have made errors in noting down the original, have made deliberate changes between collection and publication for reasons of artistic and/or moral judgement, or denied us a version considered too boring, because they were simply after yet another tune.

The kind of variation just described has been happening, I suspect, since language first evolved, and we are the better off culturally for it. It is conventional currently to call the process 're-creation', a term I find a touch strong, but will adopt in this paper. Even in the case of Chevy Chase, which bids fair to be the first authentic folk song to be recovered from the tradition (1550)![]() 18, where we have the name of the singer (Sheale), he is merely a re-creator of somebody else's earlier creation. Although the Thomson paper is entitled 'The Transmission of Chevy Chase', we are not able to glean much about the oral process, due to its having lost popularity after about 1830. However, in another paper by the same author, where the song The Foggy Dew is seen to have survived into the popular music of the mid-20th century, there is more to be learnt about the oral process, and there is a useful comparison of this with broadside transmission, including a 250 year pedigree.

18, where we have the name of the singer (Sheale), he is merely a re-creator of somebody else's earlier creation. Although the Thomson paper is entitled 'The Transmission of Chevy Chase', we are not able to glean much about the oral process, due to its having lost popularity after about 1830. However, in another paper by the same author, where the song The Foggy Dew is seen to have survived into the popular music of the mid-20th century, there is more to be learnt about the oral process, and there is a useful comparison of this with broadside transmission, including a 250 year pedigree.![]() 19

19

However, there are bigger, often more interventionist causes of variation we need to consider. Examples abound of early ballads recounting a real event, which have changed with the course of time. Thus The Gosport Tragedy has given rise to The Cruel Ship's Carpenter and the American Pretty Polly which whilst being good songs, have lost the specifics of the original![]() 20. It also has been adapted to suit a local event, as has The Captain's Apprentice.

20. It also has been adapted to suit a local event, as has The Captain's Apprentice.![]() 21 In the case of Bold Captain Avery there is evidence of changes introduced for political and moralistic reasons.

21 In the case of Bold Captain Avery there is evidence of changes introduced for political and moralistic reasons.![]() 22 It has been observed by many writers that when a song is first created, it often at first uses the tune of an existing song, and although many such songs have diverged to find their own tune by evolution thereafter, some have unashamedly stuck with the original. For example, The King of the Cannibal Islands created in the 1830s, has provided the tune for some 41 other songs

22 It has been observed by many writers that when a song is first created, it often at first uses the tune of an existing song, and although many such songs have diverged to find their own tune by evolution thereafter, some have unashamedly stuck with the original. For example, The King of the Cannibal Islands created in the 1830s, has provided the tune for some 41 other songs![]() 23 though it must be said that none of them appear to have been recovered from the tradition, and probably had only a transient broadside existence. The tune of a song will of course determine very largely its textual structure, and as a result we find families of songs related by structure. The 'Come-all-ye' format is an obvious example, but another one which has received detailed analysis is the Sam Hall/Captain Kidd grouping, where the structure of the song is apparently traceable back to Tudor times.

23 though it must be said that none of them appear to have been recovered from the tradition, and probably had only a transient broadside existence. The tune of a song will of course determine very largely its textual structure, and as a result we find families of songs related by structure. The 'Come-all-ye' format is an obvious example, but another one which has received detailed analysis is the Sam Hall/Captain Kidd grouping, where the structure of the song is apparently traceable back to Tudor times.![]() 24 Another cause of change is the 'siamesing' of several songs to make a new one. Burrison has shown how Child's James Harris arrived in the United States in about 1800, taking its title from the English The House Carpenter, but with its text a fusion of this and the Scottish The Demon Lover.

24 Another cause of change is the 'siamesing' of several songs to make a new one. Burrison has shown how Child's James Harris arrived in the United States in about 1800, taking its title from the English The House Carpenter, but with its text a fusion of this and the Scottish The Demon Lover.![]() 25 The versions collected in Britain since Child show either a similar fusion, or are firmly the Scottish version, or in one case appear to be a deliberate reworking of the original. Some of this has come about by geographical isolation, particularly with emigration to America, a situation analagous to the arrival of new species of organism by the 'founder principal'.

25 The versions collected in Britain since Child show either a similar fusion, or are firmly the Scottish version, or in one case appear to be a deliberate reworking of the original. Some of this has come about by geographical isolation, particularly with emigration to America, a situation analagous to the arrival of new species of organism by the 'founder principal'.

As stated previously, the term 'evolution' can mean the development of a complex form from a simpler original, or the proliferation of many forms, different, but not necessarily more complex. In living organisms, both meanings seem to apply, but in folksong, probably only the second meaning applies. There may be examples of songs that were born simple and got more complex by exposure to the people, but it seems that more commonly the process has been neutral in this respect, and in some cases we have inherited a 'decayed' version of a fine original. Thus Gilchrist has analysed the two distinct versions of Lambkin, Scottish and Northumbrian'![]() 26, showing how a fine song based on a real event can undergo a long period of degradation as it loses contact with the original story. Although she uses the term 'evolution' there seems no positive developmental period, only degradation, though it is not clear what part is played in this by 'creative re-working', oral transmission, or interference by collectors and editors. There must surely be a development before a decay period, but this might not happen if the song is based on a real event, as is suspected with Lambkin. In the case of John Barleycorn, a long elaborate original has been greatly simplified and shortened by positive action by an individual ('re-composition'), which has stood the test of time without further dramatic intervention.

26, showing how a fine song based on a real event can undergo a long period of degradation as it loses contact with the original story. Although she uses the term 'evolution' there seems no positive developmental period, only degradation, though it is not clear what part is played in this by 'creative re-working', oral transmission, or interference by collectors and editors. There must surely be a development before a decay period, but this might not happen if the song is based on a real event, as is suspected with Lambkin. In the case of John Barleycorn, a long elaborate original has been greatly simplified and shortened by positive action by an individual ('re-composition'), which has stood the test of time without further dramatic intervention.

The Dixon text links the 18th century English broadsides with a late Victorian recovery, in that it shows almost complete identity with the Flower of England broadside and a version collected from James Mortimore on behalf of Baring Gould in Princetown, Devon , in 1890.![]() 34 Sharp certainly recognised the importance of this link, and in the second edition of Songs of the West manipulated the Mortimore text to much more closely accord with that published by Dixon.

34 Sharp certainly recognised the importance of this link, and in the second edition of Songs of the West manipulated the Mortimore text to much more closely accord with that published by Dixon.![]() 35 A few years later in Folk Songs of England, Sharp did something similar with a version collected by Gardiner

35 A few years later in Folk Songs of England, Sharp did something similar with a version collected by Gardiner![]() 36, and in English Folk Songs he openly put Dixon's text to a splendid tune for which he only had one verse.

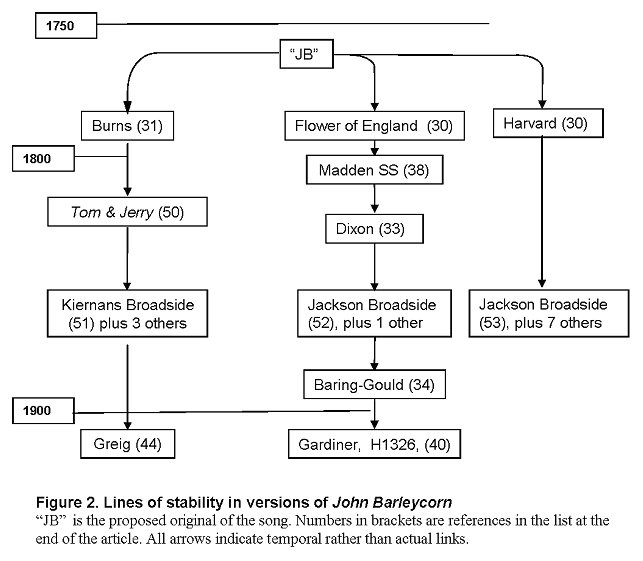

36, and in English Folk Songs he openly put Dixon's text to a splendid tune for which he only had one verse.![]() 37 Fig.2 shows this example of stability over a period of at least 140 years. There is also a hint of an older link with Allan-a-Maut, where the very last line runs: 'And it will cause a man to drink till he can neither go nor stand' in Dixon and Mortimore. The commoner final line is 'Put barleycorn in the nut brown bowl for he proved the strongest man'. The 'neither go nor stand' phrase is found twice in Allan-a-Maut, and though it is not found in the Flower of England broadside, is found in a slip-song version in the Madden collection

37 Fig.2 shows this example of stability over a period of at least 140 years. There is also a hint of an older link with Allan-a-Maut, where the very last line runs: 'And it will cause a man to drink till he can neither go nor stand' in Dixon and Mortimore. The commoner final line is 'Put barleycorn in the nut brown bowl for he proved the strongest man'. The 'neither go nor stand' phrase is found twice in Allan-a-Maut, and though it is not found in the Flower of England broadside, is found in a slip-song version in the Madden collection![]() 38 which is again undated, but almost certain to be before the Dixon publication, and is therefore included in Fig.2, which includes other examples of stability which will be discussed later.

38 which is again undated, but almost certain to be before the Dixon publication, and is therefore included in Fig.2, which includes other examples of stability which will be discussed later.

This remarkable example of stability in oral tradition is in contrast to a huge amount of change/variation amongst other versions. Only one further version saw print in books before 1900. Barrett published a version in 1891, markedly different from the Dixon text, with no information other than that it was English .![]() 39 The Edwardian collectors in southern England found John Barleycorn to be both abundant and highly variable in both text and tune.

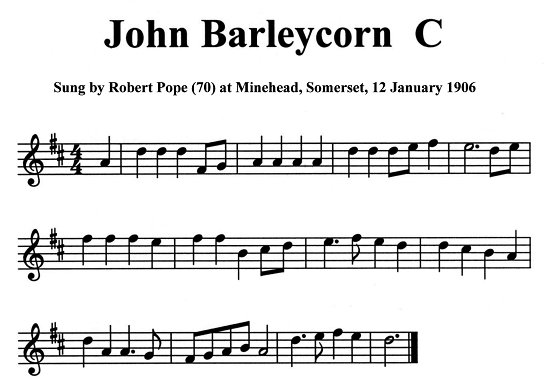

39 The Edwardian collectors in southern England found John Barleycorn to be both abundant and highly variable in both text and tune.![]() 40 Between June 1905 and December 1908, Sharp, Hammond, and Gardiner obtained 10 full texts, and 19 fragments of the song, almost all from Somerset, Dorset, and Hampshire. Other collectors garnered versions from Surrey and Sussex, with Vaughan Williams in the same period obtaining four tunes from Essex. Source singers continued to provide versions of the song up until the 1980s, adding most of the southern English counties and a couple from the north midlands to the song's distribution.

40 Between June 1905 and December 1908, Sharp, Hammond, and Gardiner obtained 10 full texts, and 19 fragments of the song, almost all from Somerset, Dorset, and Hampshire. Other collectors garnered versions from Surrey and Sussex, with Vaughan Williams in the same period obtaining four tunes from Essex. Source singers continued to provide versions of the song up until the 1980s, adding most of the southern English counties and a couple from the north midlands to the song's distribution.![]() 41

41

In species evolution, it is thought that a positive change happens say once, and is so advantageous that it spreads in a radial way geographically from the original, and is often traceable in the genes of today's organisms. Despite the debunking of the 'radial waves' concept in the spread of a tradition, notably by von Sydow![]() 42, it is important that the theory that should be regularly tested, and there are enough versions of our song for such a test. The county with the most full versions of the song is Hampshire with four. Neighbouring counties Somerset and Dorset have three and two versions respectively. Is there a discernible pattern here? Regrettably, the answer is negative. There is as much variation between the four Hampshire versions as between any two versions taken at random from the south of England. Thus the Devon version is closer to the Oxfordshire one than it is to any of the three Somerset versions next door, which themselves show no greater similarity to each other. The Sussex and Surrey versions are as different from each other as any other two, and so on. Overall, in the south of England there are nine adjacent counties providing some 42 versions, but no pattern emerges. In Northern Ireland, two quite different fragments have been collected from neighbouring villages.

42, it is important that the theory that should be regularly tested, and there are enough versions of our song for such a test. The county with the most full versions of the song is Hampshire with four. Neighbouring counties Somerset and Dorset have three and two versions respectively. Is there a discernible pattern here? Regrettably, the answer is negative. There is as much variation between the four Hampshire versions as between any two versions taken at random from the south of England. Thus the Devon version is closer to the Oxfordshire one than it is to any of the three Somerset versions next door, which themselves show no greater similarity to each other. The Sussex and Surrey versions are as different from each other as any other two, and so on. Overall, in the south of England there are nine adjacent counties providing some 42 versions, but no pattern emerges. In Northern Ireland, two quite different fragments have been collected from neighbouring villages.![]() 43 In this case, von Sydow was right-there is clearly no radial evolution of texts at work here!

43 In this case, von Sydow was right-there is clearly no radial evolution of texts at work here!

Despite its early appearance in Scotland, the song did not show particularly thereafter. Gavin Greig got one version![]() 44, with the Burns text and an indifferent tune, and later Scottish publications also tended to include the Burns version. The song has occurred patchily in Ireland, notably in O'Lochlainn

44, with the Burns text and an indifferent tune, and later Scottish publications also tended to include the Burns version. The song has occurred patchily in Ireland, notably in O'Lochlainn![]() 45 and Behan

45 and Behan![]() 46. Kennedy quotes a Tyrone singer who believed the song to be about whisky

46. Kennedy quotes a Tyrone singer who believed the song to be about whisky![]() 47, and Morton has a version from John Maguire.

47, and Morton has a version from John Maguire.![]() 48 (It is interesting to find the odd line in Irish texts seen in The Pleasant Ballad, but not in any other versions since, as in 'Some of them said drown him and the others said hang him high, for whoever sticks to the barley grain, a beggin he will die'). There are two versions from New England and one from Canada.

48 (It is interesting to find the odd line in Irish texts seen in The Pleasant Ballad, but not in any other versions since, as in 'Some of them said drown him and the others said hang him high, for whoever sticks to the barley grain, a beggin he will die'). There are two versions from New England and one from Canada.![]() 49 In all, this study has analysed some 43 separately collected full texts and a further 27 fragments, a total of 70. (There have been 46 repeats of some of the full texts, giving 116 versions in all).

49 In all, this study has analysed some 43 separately collected full texts and a further 27 fragments, a total of 70. (There have been 46 repeats of some of the full texts, giving 116 versions in all).

Here is a comparison of the 'Dixon' text and that of The Pleasant Ballad:

|

There came three men out of the West Their victory for to try And they have taken a solemn oath Poor Barleycorn should die. They took a plough and they harrowed him in, And harrowed clods on his head And then they took a solemn oath Poor Barleycorn was dead. There he lay sleeping in the ground Till rain from the sky did fall Then Barleycorn sprung up his head And so amazed them all. There he remained till Midsummer, And looked both pale and wan, Then Barleycorn he got a beard, And so became a man. Then they sent men with scythes so sharp To cut him off at knee; And then poor little barleycorn They served him barbarously. Then they sent men with pitchforks strong To pierce him through the heart And like a dreadful tragedy They bound him to a cart. And then they brought him to a barn A prisoner to endure And so they fetched him out again And laid him on the floor. Then they sent men with holly clubs To beat the flesh from his bones But the miller he served him worse than that For he ground him betwixt two stones. O! Barleycorn is the choicest grain That was ever sown on land It will do more than any grain By the turning of your hand. It will turn a boy into a man, And a man into an ass It will change your gold into silver And your silver into brass. It will make the huntsman hunt the fox That never wound his horn It will bring the tinker to the stocks That people may him scorn. It will put sack into a glass And claret in the can And it will cause a man to drink Till he neither can go nor stand. |

Yestreen, I heard a pleasant greeting A pleasant toy and full of joy, two noblemen were meeting And as they walked for to sport, upon a summer's day, Then with another nobleman, they went to make affray Whose names was Sir John Barleycorn, he dwelt down in a dale, Who had a kinsman lived nearby, they called him Thomas Good Ale, Another named Richard Beer, was ready at that time, Another worthy knight was there, called Sir William White Wine. Some of them fought in a blackjack, some of them in a can, But the chiefest in the black pot, like a worthy alderman, Sir Barleycorn fought in a boule, who won the victory, And made them all to fume and swear, that Barleycorn should die Some said kill him, some said drown, some to hang him high For as many as follow Barleycorn, shall surely beggars die Then with a plough they ploughed him up, and thus they did devise To bury him quick within the earth, and swore he should not rise. With harrows strong they combed him, and burst clods on his head A joyful banquet then was made, when Barleycorn was dead He rested still within the earth, till rain from skies did fall Then he grew up in branches green, which sore amazed them all And so grew up till midsummer, which made them all afeared, For he sprouted up on high and got a lovely beard Then he grew up till St James' tide, his countenance was wan, For he was grown unto his strength and thus became a man Then with hooks and sickles keen, into the fields they hied They cut his legs off at the knees, and made him wounds full wide Thus bloodily they cut him down from the place where he did stand And like a thief for treachery, they bound him in a band. And they took him up again, according to his kind And packed him up in several stakes, to wither in the wind And with a pitchfork that was sharp, they rent him to the heart, And like a thief for treason wide, they bound him in a cart. And tending him with weapons strong, it's to the town they hied And straight they mowed him in a mow, and there they let him lie There he lay groaning by the walls, till all his wounds were sore And at length they took him up again, and cast him on the floor They hired two with holly clubs, to beat him at once And thwacked so on Barleycorn that flesh fell from his bones And then they took him up again, to fulfill women's mind They dusted him and sifted him, till he was almost blind And then they knit him in a sack, which grieved him full sore And steeped him in a fat, Godwot, for three full days and more Then they took him up again, and laid him for to dry They cast him in a chamber floor, and swore that he would die They rubbed him and stirred him, and still they did him turn The maltman swore that he would die, his body he would burn They spitefully took him up again, and threw him on a kill, And dried him there with fire so hot, and there they wrought their will. |

Then they brought him to the mill, and there they burst his bones The miller swore to murder him, betwixt a pair of stones, Then they took him up again, and served him worse than that For with hot scalding liquor store, they washed him in a fat But not content with this Godwot, they did him mickle harm With threatening words they promised to beat him into barm And lying in this danger deep, for fear that he should quarrel, They took him straight out of the fat, and turned him in a barrel And then they set a trap to him, een though his death begin They drew out every drop of blood, whilst any drop would run Some brought jacks upon their backs, some brought bill and bow And every man his weapon had, Barleycorn to overthrow When Sir John Goodale he came with mickle might Then he took their tongues away, their legs or else their sight And thus Sir John in each respect, so paid them all their hire That some lay sleeping by the way, some tumbling in the mire Some lay groaning by the walls, some in the streets downright, The best of them did scarcely know, what they had done oernight All you good wives that brew good ale, God turn from you all teen But is you put too much liquor in, the Devil put out your een. | ||

In addition to these seven, there have been several creations which feature the name and character of John Barleycorn, including a late seventeenth century broadside entitled The Arraignment and Inditing of John Barleycorn, Knight ![]() 57, a broadside tract of 1785, A Hue and Cry after Sir John Barleycorn'

57, a broadside tract of 1785, A Hue and Cry after Sir John Barleycorn'![]() 58, a (presumed) nineteenth century broadside John Barleycorn Triumphant or The teetotallers in the dumps'

58, a (presumed) nineteenth century broadside John Barleycorn Triumphant or The teetotallers in the dumps'![]() 59, a parody of a Scottish song, John Barleycorn my Jo

59, a parody of a Scottish song, John Barleycorn my Jo![]() 60 and an interesting Suffolk chimaera of John Barleycorn with The Barley Mow

60 and an interesting Suffolk chimaera of John Barleycorn with The Barley Mow![]() 61. That the tale continues to fascinate cannot be denied. The Web gives three kinds of hits for 'John Barleycorn', one for either John Renbourne or the rock group Traffic, both of whom had albums of this title, another for one of the American early 20th century writer Jack London's characters, and the last for 'whole earth' cults who use the theme to support their philosophies. Plays have been written, and at least two 20th century poems, including one by a poet laureate.

61. That the tale continues to fascinate cannot be denied. The Web gives three kinds of hits for 'John Barleycorn', one for either John Renbourne or the rock group Traffic, both of whom had albums of this title, another for one of the American early 20th century writer Jack London's characters, and the last for 'whole earth' cults who use the theme to support their philosophies. Plays have been written, and at least two 20th century poems, including one by a poet laureate.![]() 62

62

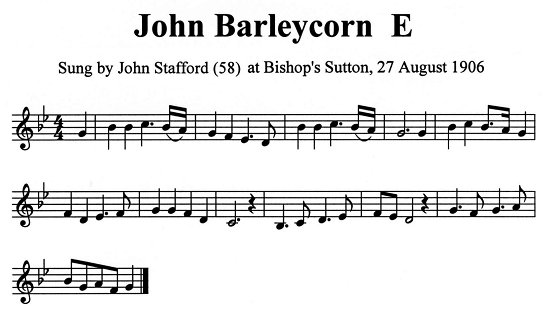

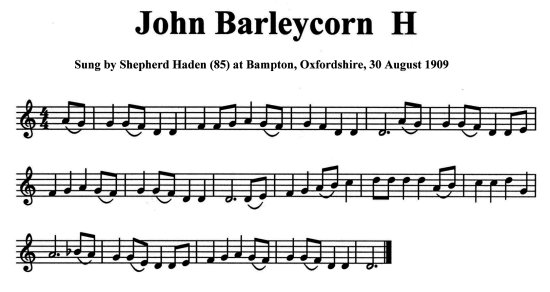

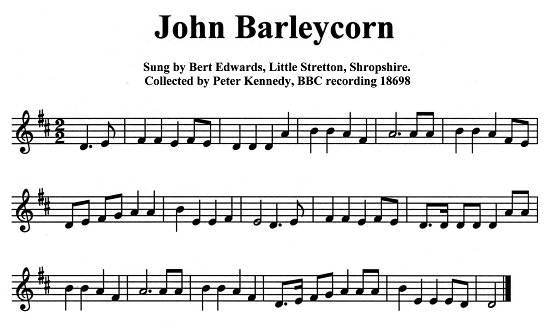

John Barleycorn has been sung to a wide range of tunes, some splendid, and some rather humdrum. The commonest tune is the one used by Vaughan Williams in his Folk Song Suite, and named by him in the score as John Barleycorn. Some 16 versions out of a total of 62 separate versions with tunes (24 per cent) have this tune or a close variant. Of the other 46, only the two Shropshire versions have the same tune. In other words, 45 different tunes have been used for this song. Some use well-known tunes, such as Dives and Lazarus, The Star of the County Down, Blow Ye Winds, and The Lincolnshire Poacher. Others, whilst not recognisable to this author, sound like hymn tunes (e.g. Christie![]() 69 and Dunston

69 and Dunston![]() 70). Other tunes are familiar to us through the intense exposure of the revival, such as a Shropshire version by Fred Jordan, a Bedfordshire version by Steeleye Span, a Lincolnshire version via the Haxey Hood ceremony, and the Dublin version by The Johnstones. Perhaps the best of this category is the Young Tradition's 1965 recording which used one of Sharp's Somerset fragments. (So taken was Sharp by the tune, that though the singer, John Stafford, could only recall one verse, the collector asked him to return a week later, when he still couldn't get beyond verse 1. But this didn't stop Sharp from using this tune in his English Folk Songs, to another text.

70). Other tunes are familiar to us through the intense exposure of the revival, such as a Shropshire version by Fred Jordan, a Bedfordshire version by Steeleye Span, a Lincolnshire version via the Haxey Hood ceremony, and the Dublin version by The Johnstones. Perhaps the best of this category is the Young Tradition's 1965 recording which used one of Sharp's Somerset fragments. (So taken was Sharp by the tune, that though the singer, John Stafford, could only recall one verse, the collector asked him to return a week later, when he still couldn't get beyond verse 1. But this didn't stop Sharp from using this tune in his English Folk Songs, to another text.

So attractive does the song remain, that it has continued to be set to different tunes or creative adaptations of existing ones in the last 50 years. Notable amongst these have been Martin Carthy, Pete Coe, and Ken Langsbury. Ken, formerly of the Gloucester group The Songwainers, tells how the rhythm of the machines in his printing shop seduced him into putting the song to the tune of We Plough the fields and Scatter, an event of singular inspiration, still recalled instantly by all those who heard the group performing the song in the late '60s.

Here are Sharp's notes about the song in his English Folk Songs:

No. 34. John Barleycorn

For other versions with tunes of this well- known ballad, see Songs of the West (No. 14 and note, 2nd ed.); Barrett's English Folk-Songs (No.8); Journal of the Folk-Song Society (volume i, p. 81; volume iii., p. 255); and Christie's Traditional Ballad Airs of Scotland (volume i., p.134).The earliest printed copy of the ballad is of the time of James I (i.e. The Pleasant Ballad). Versions with words only are given in Dick's Songs of Robert Burns (p.314); Roxburghe Ballads (volume ii., p. 327); and Bell's Ballads and Songs of the Peasantry of England (p.80). Chappell gives Stingo or Oil of Barley as the traditional air; while Dick says it is uncertain whether Burns intended his version of the ballad to be sung to that tune or to Lull Me Beyond Thee (Playford's English Dancing Master, 1st ed.).

It is not easy to express in musical notation the exact way in which the singer sang this song. He dwelt, perhaps, rather longer upon the double-dotted notes than their written value, although not long enough to warrant their being marked with the formal pause. The singer told me that he heard the song solemnly chanted by some street-singers who passed through his village when he was a child. The song fascinated him, and he followed the singers and tried to learn the air. For some time afterward he was unable to recall it, when one day, to his great delight, the tune suddenly came back to him, and since then he has constantly sung it. He gave me the words of the first stanza only.

The remaining verses of the text have been taken from Bell's Songs of the Peasantry of England [i.e. the Dixon text]. The tune, which is in the Aeolian mode, is such a fine one that I have been tempted to harmonize it somewhat elaborately. Those who prefer a simpler setting can repeat the harmonies set to the first verse.

We have no information about any oral transmission of the five ancestors of John Barleycorn, although different prints of The Pleasant Ballad show the sort of variation typical of orally-transmitted songs. We are also told by Jamieson that Alan-o-Maut was popular in north-east Scotland in the late 18th century.![]() 76 By contrast, as we have seen, we know a great deal about that of John Barleycorn, which since its arrival in the 18th century has undergone the process of 're-creation'. In this, each rendition can be seen as unique, and expected to show some variation, either of text or tune, which may be retained or rejected, consciously or unconsciously, at the next 'outing'. This aspect of John Barleycorn is explored a little later. However, the song's creation was in my view an altogether different process. The comparison of texts discussed earlier can leave no doubt that somebody methodically and skilfully reduced the length of The Pleasant Ballad, not by removing content, but by use of much more concise language more appropriate to the period. The brewing process has been removed, and the whole tone of the final part changed by inserting two verses from The Little Barley-corne and adding the 'toast' as a final verse. This is not the sort of small change described earlier as 're-creation', does not appear to happen very often with traditional songs, and should be distinguished by using a different term, such as 're-composition', a term according with at least one seminal paper on the subject of textual variation in folksong.

76 By contrast, as we have seen, we know a great deal about that of John Barleycorn, which since its arrival in the 18th century has undergone the process of 're-creation'. In this, each rendition can be seen as unique, and expected to show some variation, either of text or tune, which may be retained or rejected, consciously or unconsciously, at the next 'outing'. This aspect of John Barleycorn is explored a little later. However, the song's creation was in my view an altogether different process. The comparison of texts discussed earlier can leave no doubt that somebody methodically and skilfully reduced the length of The Pleasant Ballad, not by removing content, but by use of much more concise language more appropriate to the period. The brewing process has been removed, and the whole tone of the final part changed by inserting two verses from The Little Barley-corne and adding the 'toast' as a final verse. This is not the sort of small change described earlier as 're-creation', does not appear to happen very often with traditional songs, and should be distinguished by using a different term, such as 're-composition', a term according with at least one seminal paper on the subject of textual variation in folksong.![]() 77 Although the term 'rewrite' is inappropriate, this process is too complex a one to be achieved without its being written. It is my view that the process has created a new song, and references to The Pleasant Ballad as an 'early version' of John Barleycorn are misleading. Other scholars seem reluctant in such a case to agree with this

77 Although the term 'rewrite' is inappropriate, this process is too complex a one to be achieved without its being written. It is my view that the process has created a new song, and references to The Pleasant Ballad as an 'early version' of John Barleycorn are misleading. Other scholars seem reluctant in such a case to agree with this![]() 78, but I feel that such a quantal jump is not only quantitatively different from 're-creation', but is qualitatively different as well. It has lost the somewhat somber, dark tone of The Pleasant Ballad, and despite the beer aspect still being only a small part, it seems to be classified from this point on as a 'drinking song'. Its very sparseness and directness made it much easier for people to remember, which allowed it subsequently to become enormously popular. This conversion of long 17th century broadsides to shorter 19th century songs by re-composition as opposed to re-creation has happened with other popular folk songs such as The Nightingale and The Wild Rover.

78, but I feel that such a quantal jump is not only quantitatively different from 're-creation', but is qualitatively different as well. It has lost the somewhat somber, dark tone of The Pleasant Ballad, and despite the beer aspect still being only a small part, it seems to be classified from this point on as a 'drinking song'. Its very sparseness and directness made it much easier for people to remember, which allowed it subsequently to become enormously popular. This conversion of long 17th century broadsides to shorter 19th century songs by re-composition as opposed to re-creation has happened with other popular folk songs such as The Nightingale and The Wild Rover.![]() 79 With many songs, the record will not allow us to decide between re-creation (slow changes over a vast period of time) or re-composition (single act by one person) as responsible (compare for example Bonny Susie Cleland as a variant of Lady Maisry

79 With many songs, the record will not allow us to decide between re-creation (slow changes over a vast period of time) or re-composition (single act by one person) as responsible (compare for example Bonny Susie Cleland as a variant of Lady Maisry![]() 80).

80).

Given that somebody in the mid-18th century sat down and deliberately re-composed The Pleasant Ballad to create a new song we call John Barleycorn, do we know which was the original? Of the five 18th century versions discussed, none of them presents an overwhelming case for being the first, so the safer working hypothesis is that there is a 'missing link' from which all have derived. Putting the Burns version aside, the others show for the most part the kind of variation typical of oral transmission. However, the Jamieson and 'West' versions include verses from The Little Barley-corne which the other two lack. Either these were added later to add another dimension, as for example happened in some North American versions of Barbara Allen![]() 81, or were in an original and been dropped from the other versions. Some years before his 'antiquarian revivalist' idea, Lloyd appeared to support this view in saying that '... a song supremely beautiful, supremely dignified, and supremely candid ... taken for a drinking song ...'

81, or were in an original and been dropped from the other versions. Some years before his 'antiquarian revivalist' idea, Lloyd appeared to support this view in saying that '... a song supremely beautiful, supremely dignified, and supremely candid ... taken for a drinking song ...'![]() 82 In other words, an item of great cultural significance, nothing to do with ale, had been debased and usurped for frivolous pleasure. MacColl and Seeger also appear to support this theory, suggesting that '...the [Part C] verses had perhaps been taken from Mas Mault...' [although they manifestly meant The Little Barley-corne].

82 In other words, an item of great cultural significance, nothing to do with ale, had been debased and usurped for frivolous pleasure. MacColl and Seeger also appear to support this theory, suggesting that '...the [Part C] verses had perhaps been taken from Mas Mault...' [although they manifestly meant The Little Barley-corne].![]() 83 I prefer deletion, as it accords with my concept of an outstanding single act of re-composition, but the evidence will not allow a decision. If it was a later addition, then it happened very quickly after the first act of re-composition.

83 I prefer deletion, as it accords with my concept of an outstanding single act of re-composition, but the evidence will not allow a decision. If it was a later addition, then it happened very quickly after the first act of re-composition.

Another intriguing aspect is the first line, which has been used so far as a label to identify variants, but as argued earlier, first lines have special significance and so require some attention. If 'Three Knights North' was the original, then why such a rapid change to 'Three Kings East' in oral tradition in Scotland by the 1770s, and 'Three Men West' and 'Two Brothers on yonder Hill' in English broadsides at about the same time? As the introduction outlines, change can be subconscious mainly due to loss of memory on the part of a singer. (i.e. any point of the compass would do, did it matter if they were knights, kings, or men?, etc.), or deliberate. If the latter, can we detect reasons other than artistic preference? Speculation has suggested the West because it means sunset, or place of death, whilst the Wise Men came from the East (sunrise, place of life?) bringing promise of death to the infant Jesus. However, there seems to be little support for these ideas. 'Two brothers on yonder hill' has only occurred once again, in the Lincolnshire Haxey Hood version, but apart from the first verse, the version has no resemblance to the 18th century broadside.

As has already been pointed out, the 43 full versions of John Barleycorn considered here manifest both stability and change. What is clear from the analysis in this paper is that three of the '18th century five' led to lines of stability as shown in Fig.2. Two of these were print-based, leaving only 'Three Men West' featuring strongly in oral tradition, particularly in southern England. Although Fig.2 suggests a route by which the broadside and oral tradition of 'Three Men West' may have reinforced each other, the former is very limited, and further doubt is cast upon this idea by the fact that the commonest mid-19th century broadside text has not been recovered from the tradition.. The same is true of Hey John Barleycorn, which was very common as a broadside in the mid-19th century, but has rarely been found in oral tradition.

If broadsides in general have not played a significant part in the oral tradition of this song, it may well explain the vast amount of variation in the versions recovered in the early 20th century, in keeping with other studies.![]() 84 Interestingly, the variation does not show any of the decadence which has elsewhere been attributed to the lack of a printed version, such as Lamkin and The Foggy Dew

84 Interestingly, the variation does not show any of the decadence which has elsewhere been attributed to the lack of a printed version, such as Lamkin and The Foggy Dew![]() 85. This may be explained by our song being a metaphor whereas Lamkin is based on a real event whose details have been lost, and that the interpretation of the term 'foggy dew' is somewhat uncertain.

85. This may be explained by our song being a metaphor whereas Lamkin is based on a real event whose details have been lost, and that the interpretation of the term 'foggy dew' is somewhat uncertain.

It had been hoped that the tunes might have helped in the search for an evolutionary path. Whilst the 16 versions which use the John Barleycorn tune are located in the West country, most of them are fragments collected by Sharp in Somerset, which makes the search for textual similarity between them difficult, and the full texts using this tune show no greater kinship than do the population as a whole. However, the fact that there are so many reflects the song's great popularity.

Returning to the geography of the song, it is notable that it is absent from great swathes of the Midlands and North. Either nobody looked for it in these areas, or it wasn't there to be found. The former is supported by the fact that counties such as Suffolk, Gloucestershire, and Shropshire, which had not been collected in the first revival of the 1900s, yielded versions in the second revival after 1950. However, this probably does not apply to the northernmost English counties, which each had at least one notable 19th century collection of folksongs. There were also mid-19th century broadside versions in Birmingham, Preston, Manchester and Newcastle, and a print of Mountain of Hair in Newcastle, which perhaps reinforces the idea that for this song the later broadsides had very little influence over the oral tradition. In the case of the north-east, the area has had more printed versions of ballads and songs over the last two hundred years than any other area of England, and yet John Barleycorn does not show. This is particularly puzzling given its proximity to Scotland, which as we have seen had a thriving tradition of the song in the 18th century.

Of course, we should remind ourselves that working people did not generally travel much, unless they were drovers, journeymen, seasonal agricultural workers, merchants and the like. Although several people have suggested these as major transmitters of songs, this is not supported by our song; some of the most major droving routes being across the English/Scottish border. Perhaps the singers didn't drove? Why, if it was widespread in Scotland before 1800, and in Devon before 1846 was it not in Northumberland? One tempting possibility is maritime transfer by reason of war. One thing that the Napoleonic wars achieved, as did all wars, was to put men together from all over the Kingdom. The few who survived would probably have had to take their chance on repatriation, so that many Scots soldiers may have been discharged at the most convenient naval port, i.e. Plymouth or Portsmouth. They might have eventually got back home, or might have stayed down south. Either way, if John Barleycorn was a Scots song, here is a means by which it might have become a west country English song. Of course, it might have happened the other way, and anyway these men would have swapped songs whilst thrown together in barracks and holds all over Europe.

As discussed earlier, Hey John Barleycorn has demonstrated total stability since its creation in the mid 19th century, but John Barleycorn is more interesting. Here we find the widest variation in both text and tune. Whilst much of this has been due to conscious changes by singers and songwriters, it is also likely that, as argued in the introduction, many changes have been by forgetfulness or subconscious change of a word and these are much more like the randomness of mutations in DNA. But, whatever the causes of the changes, the third aspect of evolution, selection has played its part. If a singer makes a change on one occasion and prefers it, he'll keep it, if the audience prefers one version over another, it will be requested more, and so on. We have also seen a very good example of stability over about 120 years from Flower of England via the Dixon version to the Devon version of the 1890s. I like to see this as selection by the people rather than the professionals, though without evidence of course. But this line also shows selection by these people in what Sharp did to the Mortimore version when he published it.

Pete Wood - 11.2.10

using material written in 2004 but not previously published

peter@pwood49.fsnet.co.uk

2. Cecil J Sharp, English Folksong: some conclusions. (London: Barnicott and Pearce, 1907). 3rd Edn rev. Maud Karpeles (London, Methuen & Co., 1954) pp.17-31.

3. See for example Anne G. Gilchrist, ''Lambkin': A Study in Evolution', Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, 1(1932), 1-17; Robert S. Thomson, 'The Transmission of Chevy-Chase', Southern Folklore Quarterly, 39 (1975), 63-82.

4. Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection, (London: John Murray, 1859).

5. Sharp, pp.16-18.

6. Ian Russell, 'Stability and Change in a Sheffield Singing Tradition', Folk Music Journal, 5.3 (1987), 317-53.

7. Robert S Thomson, 'Development of The Broadside Ballad Trade……' Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 1975. No.9047, pp 17-21.

8. Bertrand H Bronson, 'Mrs Brown and the Ballad' in The Ballad as Song, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), pp 65-78; David Buchan, The Ballad and the Folk, (London:Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972) 2nd edn. (East Linton:Tuckwell Press, 1997) pp.62-73.

9. Bronson, p.67.

10. Eleanor R Long, 'Ballad Singers, Ballad Makers and Ballad Etiology', Western Folklore, 32 (1973), pp.225-36.

11. Gilchrist, p.17.

12. Sharp, pp.29-31.

13. Russell, pp.324-326.

14. Sharp p.20.

15. A L Lloyd, Folk Song in England, (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1967), p.15.

16. Lloyd, p.16.

17. Russell, p.335.

18. Thomson, 'Chevy Chase', pp.63-82.

19. Robert S Thomson, 'The Frightful Foggy Dew', Folk Music Journal, 4(1980), 35-61.

20. David C Fowler, 'The Gosport Tragedy': Story of a Ballad'. Southern Folklore Quarterly, 43 (1979), 157-196.

21. Elizabeth James, ''The Captain's Apprentice' and the Death of Young Robert Eastick of King's Lynn: A Study in the Development of a Folk Song'. Folk Music Journal, 7 (1999), pp.579-594.

22. Joel H Baer, 'Bold Captain Avery in the Privy Council: Early Variants of a Broadside Ballad from the Pepys Collection'. Folk Music Journal, 7(1995), 4-26.

23. Anthony Bennett, 'Rivals Unravelled: A Broadside Song and Dance', Folk Music Journal, 6.4 (1993), 420-45.

24. Bertrand H Bronson, 'Samuel Hall's Family Tree', reprinted in The Ballad as Song (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), pp.18-36.

25. John Burrison, ''James Harris in Britain since Child'. Journal of American Folklore, 80 (1967), 271-284.

26. Gilchrist, pp.1-17.

27. Bannatyne mss (1568) (reprint Glasgow: Scottish Text Society, 1928) p.306.

28. Pepys Black Letter Broadside Collection, Pepysian Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge University Vol.I p.426.

29. Mountain of Hair Garland, (Robert White Collection, Newcastle University Library, 17:77, nd; BL 1162, c4, c 1775).

30. 'John Barleycorn, The Flower of England', 18th Century broadside, nd, no printer, (Madden Collection, BL 26, 22); Houghton Library, Harvard University, Broadside Ballad Collection, 28:4.

31. Robert Jamieson, Popular Ballads and Songs, (Edinburgh: A Constable and Co.; Cadell and Davies; and John Murray, London, 1806) Vol.2, p 231-239.

32. Alexander Whitelaw, The Book of Scottish Ballads (Glasgow : Blackie, 1845) pp.284-285; William Christie, Traditional Ballad Airs (Edinburgh : Edmonston & Douglas, 1877) Vol.I, pp.134-135.

33. James H Dixon, Ancient Poems, Ballads and Songs of the peasantry of England, (London : C. Griffin and Co., 1846), p.120-122.

34. Baring Gould mss, Plymouth City Library, K2 p.92, No.157.

35. Sabine Baring Gould, Songs of the West (London: Methuen & Co., 2nd Edn, 1905) pp.5-6, 28.

36. G Gardiner, mss H293; Cecil J Sharp, Folk Songs of England, (Novello & Co. 1909), pp.24-25.

37. Cecil J Sharp, English Folk Songs, (London: Novello & Co. 1920), Vol.2, pp.82-87.

38. Slip Songs O-Y [VWML mfilm No.73] Item no.1717, Madden Collection, nd.

39. William Alexander Barrett, English Folk Songs, (London: Novello & Co., 1891), pp.14-15.

40. Examples of full texts collected between between June 1905 and December 1908 include the following: Cecil J Sharp, mss, pp.976-977, 1455-1456, and 1772-1773; H E D Hammond, mss D364 and D414; G Gardiner, mss H293, H651, H492, H1326. (A list of versions considered in this paper may be obtained from the author).

41. Examples of full texts collected after 1908 include: Alfred Williams, Folk Songs of the Upper Thames (London: Duckworth, 1923) pp.246-247; Peter Kennedy, Folksongs of Britain (London: Cassell,1975 (coll. Kennedy 1952)), pp.608, 627; John Howson, Songs Sung in Suffolk (Stowmarket: Veteran Tapes, 1992), pp.72-73; Roy Palmer, Everyman's Book of English Country Songs (London: Dent, 1979 (coll. M Yates, 1974)), pp.193-194.

42. Carl Von Sydow, 'On the Spread of Tradition' in 'Selected papers on Folklore', Copenhagen, Rosenkilde & Bagger, 1948 pp 11-43.

43. Robin Morton, Some Day Go Day, (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973), p.160.

44. Pat Shuldham-Shaw, et.al., The Greig-Duncan Collection (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1983) Vol.3 p.375.

45. Colm O'Lochlainn, Irish Street Ballads, (Dublin: The Three Candles Ltd.,1939), p.176.

46. Dominic Behan, Ireland Sings (London: Essex Music Ltd., 1965) p.89 .

47. Peter Kennedy, Folksongs of Britain (London: Cassell,1975 pp 627-628.

48. Morton, p.32.

49. Helen H Flanders, & George Brown, Vermont Folk-Songs and Ballads (Brattleboro: Stephen Daye, 1931; 2nd edn. 1932), pp.46-48; Helen H. Flanders, et. al., New Green Mountain Songster: Traditional Folk Songs of Vermont; (New Haven: Yale U.P., 1939), p.259; Edith Fowke, Traditional Singers and Songs from Ontario; (Hatboro: Folklore Assocs., 1965), pp.14, 161.

50. Tom & Jerry, garland for Theatre Royal Newcastle, printer J. Marshall Newcastle, Robert White Collection, Newcastle University Library, [1825-29].

51. Harding B36 (25), printer J Kiernans, Manchester, Bodleian Library.

52. Johnson Ballads 2847, printer Jackson, Birmingham, Bodleian Library, 1842-1855.

53. Johnson Ballads 1408, printer Jackson, Birmingham, Bodleian Library, 1842-1855.

54. Steve Gardham, personal communication.

55. Examples include: Harkness, Preston, in Harding B20, Bodleian Library,1840-66; Fortey London, in Harding, B11(3188), Bodleian Library, 1858-85, Disley, London, in Harding B15 (150), Bodleian Library, 1860-83.

56. Robert Ford, Vagabond Songs and Ballads of Scotland, (Paisley: Alexander Gardner, 1899), pp.227-229; Kennedy, p 609; Bob Copper, Songs and Southern Breezes, (London: Heinemann, 1973) pp.216-217; Flanders et. al. New Green Mountain Songster, p.259.

57. A chapbook printed by Thomas Robbins which includes a part-song-part prose item called 'The Arraignment and Inditing of Sir John Barleycorn, Knight', Olsen Index ZN3428. It is also in Roxburghe Ballads Vol.7, p.587, which cites 'earliest source' as a Thomas Passenger print of 1675. Also in Ashton's Chapbooks, p.314, and in Harvard University Houghton Library, Catalogue No.1728-32.

58. 'A Hue and Cry after Sir John Barleycorn ...' Halliwell-Phillips, Chetham's College Library, Manchester, No.3038.

59. 'John Barleycorn Triumphant or The teetotallers in the dumps', W & T Fordyce, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1837-38.

60. Shuldham-Shaw, p.448.

61. John Howson, Songs Sung in Suffolk (Stowmarket: Veteran Tapes, 1992), p.121.

62. George MacKay Brown, A Spell for Green Corn, (London: Hogarth Press, 1970); George MacKay Brown, 'The Ballad of John Barleycorn, the Ploughman, and the Furrow', in Penguin Modern Poets, Series No.21 (London: Penguin Books, 1972); Ted Hughes, 'The Golden Boy' in Season Songs, (London: Faber, 1976).

63. Pepys, p.426.

64. Claude Simpson, The British Broadside Ballad and its Music (New Brunswick, N.J : Rutgers University Press, 1966) p.688.

65. William Chappell, Popular Music of the Olden Time, (London: Cramer, Beale, and Chappell, 1858-59), Vol.1, p.305.

66. Roxburghe Ballads, (Hertford: Ballad Society, 1871-1897), 'The Pleasant Ballad' Vol.2 p.372, Vol.3, pp.360, 364. 'Mas Mault', Vol.2, pp.373 Vol.3, p.361, 365.

67. See Baring Gould, pp.6-7.

68. Euing Collection, (Glasgow: University of Glasgow Publications, 1971), 'Mas Mault' p.277.

69. William Christie, Traditional Ballad Airs (Edinburgh : Edmonston & Douglas, 1877) Vol.I, pp.134-135.

70. Ralph Dunston, The Cornish Songbook, (London: Reid, 1929) p.56.

71. Gilchrist, notes in FSJ; Chris Lyons, 'The Myth of Orisis', Bristol Folk News, No.11, 1973, pp.3-5.

72. Kennedy, pp.627-628.

73. Palmer, p.192; MacColl & Seeger, p.305; Tom Randall, Bristol Folk News, No.11, 1973, pp.9-11.

74. A L Lloyd, Penguin Book of English Folk Songs, (London: Penguin Books, 1959), p.116.

75. Gilchrist, 'Lamkin', pp.1-17; Thomson , 'Frightful Foggy Dew', pp.35-61.

76. Jamieson, p.231.

77. Thomas A Burns, 'A Model for Textual Variation in Folksong', Folklore Forum, 3 (1970), 49-56, esp. p.55.

78. Philip V Bohlman, The Study of Folk Musk in the Modern World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), p.19; Burns, p.51.

79. Thomson, 'Broadside Ballad Trade', pp.215-263.

80. Francis J Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, (New York: Dover Press, 1965) Vol.2 pp.112-126.

81. Christine A Cartwright, 'Barbara Allen': Love and Death in an Anglo-American Narrative Folksong'. Narrative Folksong: New Directions. Essays in Appreciation of W Edson Richmond. Ed. Carol L Edwards and Kathleen E B Manley. (Boulder: Westview Press, 1985, p.251).

82. A L Lloyd, The Singing Englishman, (London: Workers' Music Association Ltd., 1944), pp 28-29. Republished in Musical Traditions Internet Magazine, Article MT134, 2.1.04.

83. MacColl & Seeger, p.306.

84. Thomson, 'Broadside Ballad Trade', pp.22-23.

85. Gilchrist, 'Lamkin', pp.1-17.

Article MT232

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |