Article MT200

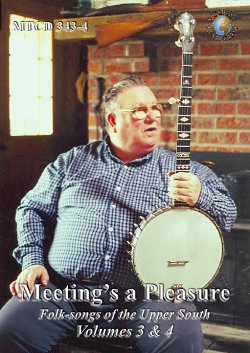

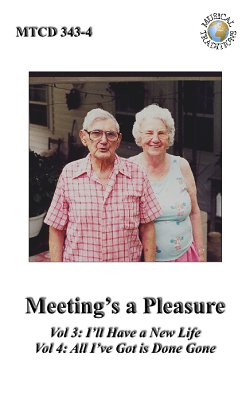

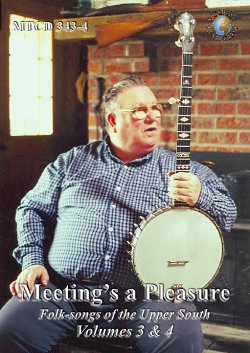

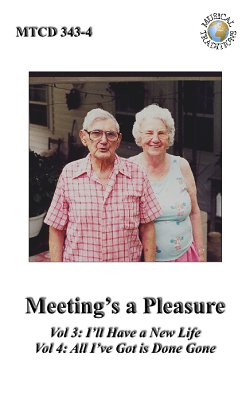

Meeting's a Pleasure

Folk-songs of the Upper South

Volumes 3&4

Dedicated to the memory of Annadeene Fraley

Musical Traditions Records' first release of 2007 is the 4-CD set: Meeting's a Pleasure: Folk-songs of the Upper South (MTCD341-2 and MTCD343-4), which is now available. See our Records page for details. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the records, or who might find the small print hard to read, I have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here.

[Track Lists]

[Introduction]

[CD Three]

[CD Four]

[Credits]

Vol 3:

1 -

2 -

3 -

4 -

5 -

6 -

7 -

8 -

9 -

10 -

11 -

12 -

13 -

14 -

15 -

16 -

17 -

18 -

19 -

20 -

21 -

22 -

23 -

24 -

25 -

| I'll Have a New Life

Farther Along

Little Bessie

Wandering Boy

The East Bound Train

I Know Somebody's Going to Miss Me when I'm Gone

Mother's Grave

Darling Little Joe

The Evening Train

The Day is Past and Gone

Motherless Children

In a Foreign Heathen Country

Robinson Crusoe

The Unclouded Day

Keys to the Kingdom

Little David, Play on your Harp

I'll Have a New Life

While Passing a Garden

In my Father's House

I'm Drinking from the Fountain

I Feel Like Traveling On

Walk around my Bedside, Lord

There was a Man in Ancient Times

The Old Churchyard

We'll Understand it Bye and Bye

Day is Breaking in my Soul

|

The Dixon Sisters

Buell Kazee

Sarah Gunning

The Dixon Sisters

Perry Riley

Earl Barnes with the Cumberland Rangers

Blanche Coldiron

Annadeene Fraley

Wash Nelson

Roscoe Holcomb

Sarah Gunning

Jim Garland and Sarah Gunning

J P Fraley

Francis Gillum

Jim Garland and Sarah Gunning

John Lozier

Mary Lozier

Henry Hurley

Nimrod and Mollie Workman

The Dixon Sisters

Roscoe Holcomb

Mary Lozier

Sarah Gunning

The Dixon Sisters

Nimrod Workman

|

3:12

5:44

3:43

1:50

2:38

2:07

2:32

2:55

2:40

2:53

2:17

1:38

1:40

3:09

1:27

0:59

4:40

3:05

3:07

2:17

3:11

4:29

2:20

2:20

4:46

|

|

| | | Total: | 71:37

|

|

Vol 4:

1 -

2 -

3 -

4 -

5 -

6 -

7 -

8 -

9 -

10 -

11 -

12 -

13 -

14 -

15 -

16 -

17 -

18 -

19 -

20 -

21 -

22 -

23 -

24 -

25 -

26 -

27 -

28 -

29 -

30 -

31 -

32 -

33 -

34 -

35 -

36 -

37 -

| All I've Got is Done Gone

The Yellow Rose of Texas

Davy Crockett

The Jam on Gerry's Rocks

My Home in the West

Cumberland Gap

Lorena

This Little Light of Mine

Blackberry Blossom

Marching Through Georgia

Brother Green

Morgan on the Railroad

The Dying Cowboy

Garfield March

I Believe I'll Sell this Farm, Jane Ann

Hard Times

There's a Hard Time Coming

"One More Trip" said the Sleepy Headed Driver

The Hard Working Miner

Chinese Chimes

Dusty Skies

The Carter County Tragedy

F D R Reelection Song

Old Age Pension Check

All I've Got is Done Gone

Graveyard Blues

Coal Creek

Notes (Slow Blues)

Chittling Cooking Time in Cheatem County

Got Up this Morning

Black Dress Blues

All Night Long

Boat Up the Water

St Louis Blues

Old Hannah

The Coburn Fork of Big Creek

My Peach Trees are all in Bloom

Turkey in the Straw

|

J P Fraley, Bert Garvin and Group

The Dixon Sisters

Wash Nelson

Jim Garland

Earl Thomas and Billy Stamper

Margie and Gene York

The Dixon Sisters

J P and Danielle Fraley

Blanche Coldiron

Mildred Tucker

Roger Cooper

Hobert Stallard

Ray Hilt

Jim Garland and Sarah Gunning

Mary Lozier

Perry Riley

Jim Garland

Sarah Gunning

Roger Cooper

Annadeene Fraley and Daughters

Wash Nelson

Abe Keibler

Nova and Lavonne Baker

Van Kidwell and Asa Martin

Roscoe Holcomb

Manon Campbell

Henry Hurley

Snake Chapman

Asa Martin

Nimrod Workman

George Hawkins

John Lozier

John Lozier

George Hawkins

Michael Garvin

Roger Cooper

Roger Cooper and Michael Garvin

|

1:31

1:07

2:17

2:45

2:01

2:53

2:28

2:35

1:36

1:31

1:23

1:12

2:07

1:20

0:56

1:25

1:04

3:10

1:30

3:07

2:44

1:01

2:00

2:06

3:02

1:26

1:16

1:15

4:03

2:25

1:28

0:42

1:36

0:54

1:46

1:27

2:20

|

|

| | | Total: | 69:21

| |

Introduction:

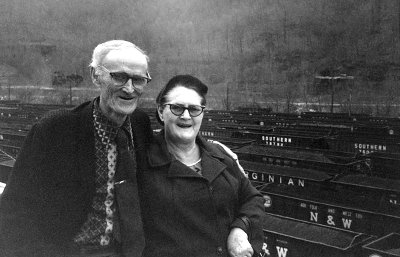

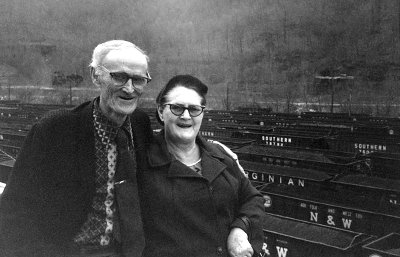

Before she died ten years ago, I promised Annadeene that someday I would dedicate a set of the recordings that we had made together in her honor, in appreciation for her vital assistance in my group's attempts to preserve portions of Kentucky's older musical culture. Over the years quite a few local people have aided Gus Meade, John Harrod and me in our endeavors and we remain deeply grateful to all of them. However, no one has helped us more assiduously than Annadeene, who located performers that she may not have known herself previously and who often went along on the field trips with me. But considerable poignancy lay masked behind this cheerful assistance, for Annadeene harbored her own share of musical ambitions and would have been happier if some larger share of own singing could be released by the Boston company with which these bearded strangers were somehow associated (viz, Rounder Records). Annadeene was musically talented and was widely admired within her Kentucky community, but she specialized in the sorts of modern 'folk festival' presentations that were simply not what we or the record company sought. Or, to frame the situation more accurately, by the mid '90s, Rounder had enjoyed 'hits' in a 'folky' vein somewhat akin to Annadeene's, but I never played any role in those sorts of production - indeed, I never met most of the parties responsible for such records (I have instead been employed at sundry universities in faraway towns). Once in a while back in the '70s Rounder's Bill Nowlin or Ken Irwin would accompany me on a recording trip, but I otherwise worked independently of the company and their internal deliberations have remained quite mysterious to me. But I was morally certain that I could only 'sell' them projects considerably more 'countrified' than Annadeene's core fare (indeed, as noted in volume 1, early on I experienced resistance along this line even with respect to Buell Kazee's music). In any case, Gus, John and I never conceived of ourselves as budding impresarios: our overriding intention was simply to get as much of Kentucky's vanishing older heritage recorded and issued as possible (I usually characterize my record contributions as that of 'producer', but only because the more reasonable term 'folk song collector' is now commonly eschewed with undeserved disdain within academic circles in the United States).

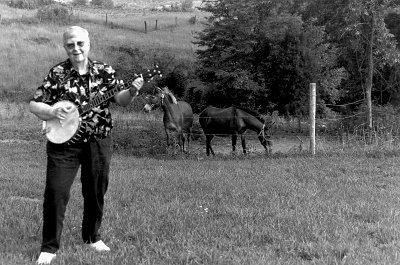

I imagine that our musical requirements proved doubly grating to Annadeene, in light of the fact that her husband J P's fiddle music did appeal to Rounder's essentially urban audience. As a canny observer, she was firmly aware that some of these citified preferences traced to misapprehensions about 'folk music's' true circumstances within Kentucky. When I read modern criticisms of the major 'folk song collectors' of the past, I am often annoyed by their moralizing tenor, for such commentary seems oblivious to the fundamental problems of equipment, time, money and human motivation that invariably constrain endeavors of this ilk. Why, after all, should anyone expect that busy Kentuckians would wish to assist urban interlopers in 'preservation projects' without clear benefit to themselves: activities that, by their very nature, raise considerable suspicions of cultural exploitation? Annadeene and I discussed issues of this type quite candidly and I thought that I might simultaneously honor her contributions to our recording work and supply a more realistic portrait of 'folk song collecting' in the modern era if I sketched our interactions with the Fraleys more fully in this introduction.

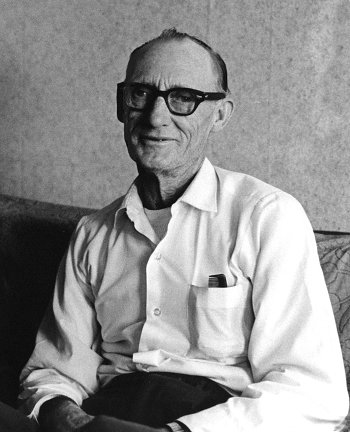

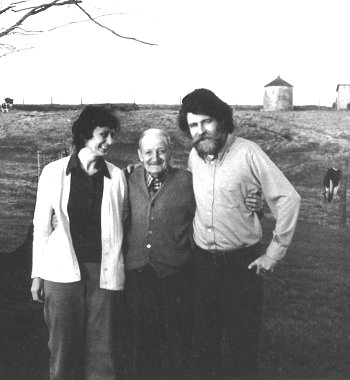

J P and Annadeene were born in the early depression to small town families during an era when traditional music could be readily encountered locally, although its character was rapidly shifting. All the same, the childhood circumstances of the Fraleys were quite different from those experienced by Jim Garland and his sister Sarah, who were fifteen years older than the Fraleys and had been raised in a more constrained mountain environment (these dissimilarities reflect changing times as much as geography: as a girl Annadeene had lived for a period in southeastern Kentucky, but by then she enjoyed far more access to the outside world than the Garlands had). Accordingly, neither J P nor Annadeene was ever confined to an exclusive diet of family-based music, as often proves the case for musicians who possess very large stocks of old songs. J P's home music background derived largely from his father, Richard, and his circle of friends, who were country fiddlers in the mold of Alva Greene (no recordings of Richard are known to exist, unfortunately). I am less certain of the exact measure of music that Annadeene experienced within her own family circle: they had traveled around the coal camps of both Kentucky and West Virginia quite a bit before she returned to Star Branch, Kentucky for high school. She had several relatives that played on early West Virginia radio and these seem to have made the biggest early impression upon her (her beautiful Martin guitar had descended through the family from one of these musicians). In their teenage years J P and Annadeene gravitated independently (they were not a couple then) to more 'progressive' forms of music: specifically, to tight harmony groups in the mold of the Sons of the Pioneers. Annadeene also liked to listen to big band singers on radio like Rosemary Clooney (who came from nearby Maysville and was a childhood friend of the Dixon family). In fact, Annadeene once told me that, more than anything, she would have liked to have been a popular singer in such a mold, although, as she once told me humorously, 'we could never figure out the chords to those songs'. In truth, Annadeene had both the voice and the looks to have proved successful in these ambitions, had she not been born just a little too late (the true big band era effectively ended with World War II). J P himself much enjoyed playing 'western music' and, in later years, liked to listen to Stephane Grappelli and Eddie South.

It is important to appreciate that, although a good detail of indubitable 'folk music' could be readily found throughout the Fraleys' home region, it coexisted, quite happily in this period, with more uptown forms of music. A few examples: the great jazz violinist Stuff Smith was raised in Portsmouth, Ohio; the skilled fiddler Jimmie Wheeler (from whom J P and Roger Cooper learned many tunes) played bass and guitar in popular music orchestras where he learned to follow their complex charts; a relative of J P's named 'Big Foot' Keaton played excellent swing fiddle on a local radio program. And so on. As a result, although J P undoubtedly heard a fair amount of backwoods fiddling within his father's entourage, he did not attempt to imitate much of it nor did Dick Fraley encourage that he do so (in my experience, fiddle playing parents generally spur their children to develop the instrumental skills heard on the radio, rather than imitate their own more rustic techniques). In Annadeene's case, I always thought that she sounded best when she sang songs suited to the light, country swing sound that she had preferred as a youngster. Not too long before she died, I located a copy of a record that Annadeene had much admired: Jo Stafford Sings American Folksongs. And it struck me as we listened together to Paul Weston's gorgeous settings that here was an Americanized form of art song to which Annadeene would have been perfectly suited, had circumstances proved favorable, for such arrangements would have allowed her to express her affection for her homeland and its traditions in a dignified manner consistent with the level of her musical sophistication.

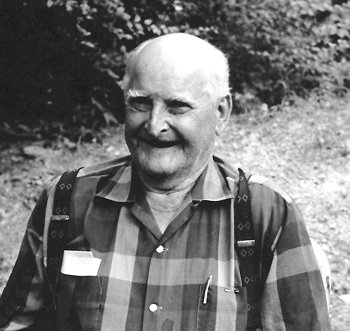

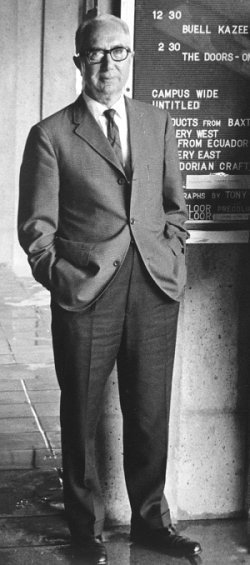

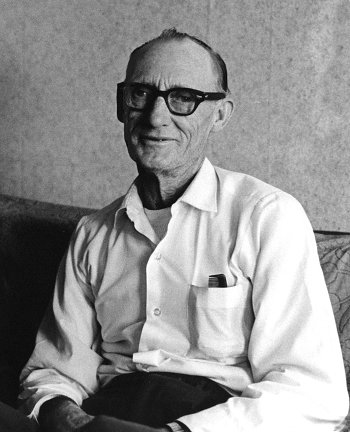

As these natural processes of modernization were unfolding, a simultaneous campaign urged Kentuckians to take pride in their older forms of music. In fact, the well springs of this movement had begun long before, in the guise of the local color pieces appearing in the late nineteen century editions of Scribner's Magazine and the like, which often featured snatches of folk song prominently. Sentimental novels like The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come of 1910 inspired musical 'pageants' designed to draw tourists into Appalachia and college courses on 'ballad literature' encouraged Kentuckians to take pride in the fact they had retained a large degree of British folk culture through oral tradition. Nowadays these representations are often mocked for their inaccuracies but we should never forget that such infusions of 'local pride' once meant a good deal to a young country boy like Buell Kazee, who had advanced, through a dedicated schedule of self-education, from humble circumstances to a comfortable position as a Baptist minister in upscale Winchester. Rev Kazee retained the fondest memories of his Magoffin County upbringing but he was also proud that he had matured into an adult of considerable talent and accomplishment. It therefore pleased him when he was invited to deliver Chatauqua style lectures that combined narration and song in a manner that portrayed his childhood circumstances within a respectful setting (The Inconstant Lover on volume 1 is drawn from one of these public presentations). Ray M Lawless in his 1960 Folksingers and Folksongs in America paraphrases his opinions as follows:

Kazee reports that when he first went to college, he was somewhat ashamed of the old songs; but, after a course in Shakespeare, he found himself at home in the Elizabethan world and therefore began studying and singing the old songs as cultural matter.

Indeed, one of the several factors that later troubled Rev Kazee about the 'folk revival' of the 1960s is that, through its infusion of politically charged content, he felt that his beloved 'folk songs' were being stripped of their dignity-conferring value. And I think we fail to understand Appalachia's struggles properly if we do not see some justice in that complaint. However absurd some of those early characterizations of 'folk song' were (and we'll survey some of these in a moment), we should not discount their positive utility in allowing rural Kentuckians a measure of self respect that was otherwise often denied them.

In the Boyd and Carter County region, the chief locus for these kinds of improving 'folk song' atmospherics came invested in the form of the entrepreneur Jean Thomas and her American Folksong Festival. By any rational standard, this represented a quite surreal affair, as any random quotation from the stage instructions for her 'pageant' indicates:

The Ladies-in-Waiting (Episode IV in the Festival) are attired in full-skirted, tight-bodiced, black frocks, with white ruff at neck and sleeve. The Narrator, in Elizabethan costume, is speaking the Prologue, which sets forth the English origin of the ballads and mountain minstrels (from The Singin' Gatherin').

Probably Thomas' strangest impulse was to seize upon a local blind street musician, J W Day, and convert him into a literary fabrication ('Jilson Setters') who spoke as if he had fallen from the pages of The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come. The real Bill Day played a vital role in the musical life of eastern Kentucky and we have already encountered him several times in our tune histories.

In their youth, the Fraleys paid little attention to any of this. As a young boy, 'Miss Thomas' asked J P's parents if the young fiddler might appear in her festivities, but J P didn't want to bother with anything so stuffy as that. Annadeene commented:

We really hadn't heard that much about the folk festival - local people just didn't pay that much attention to it, but newspaper people, lawyers and folks like that would come in from other states, even countries from afar. Now in our minds, the festival was famous, but it just didn't seem like something we went to. Ashland also had the notion that she was making fun of Kentucky and that influenced everybody as well. They thought she was making fun of us by dressing the performers in period costumes and so forth. My goodness! Children would go barefoot on stage (as if I didn't go through the whole summer without any shoes myself).

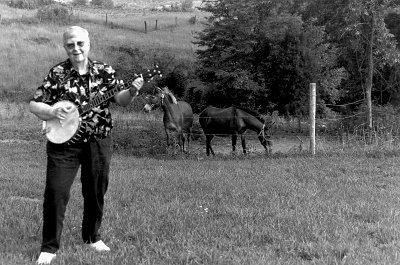

In fact, during the early days of their marriage neither J P nor Annadeene played much music. They had four kids to raise and J P labored in the local brickyard while Annadeene sometimes worked in a sewing factory.  It was only through a combination of hard work and ingenuity that their economic lot in life gradually improved. Eventually the brick yards shut down and J P went to work for a company that manufactured the huge continuous miners that extract the coal in our underground mines (J P had done a bit of mining when he was young). Because J P was both extremely smart and gifted with people, he gradually advanced within the company until they regularly asked him to travel as their representative to locales all over the world where the big machines were being installed. Eventually these promotions provided the Fraleys with a quite comfortable way of life. Sometime in the middle '50s J P had entered a local fiddle contest on a whim and won it, much to his surprise as he was utterly out of practice (J P spins the tale hilariously on our NAT website). Pretty soon a guitarist named Hubert Rogers asked him if he wanted to form a square dance ensemble for the dances across the river in Ironton, Ohio. Soon thereafter the group asked Annadeene to sing country-western songs for the round dance interludes. Hubert Rogers had had prior dealings with Jean Thomas and that is how the Fraleys came to meet her in the early '60s.

It was only through a combination of hard work and ingenuity that their economic lot in life gradually improved. Eventually the brick yards shut down and J P went to work for a company that manufactured the huge continuous miners that extract the coal in our underground mines (J P had done a bit of mining when he was young). Because J P was both extremely smart and gifted with people, he gradually advanced within the company until they regularly asked him to travel as their representative to locales all over the world where the big machines were being installed. Eventually these promotions provided the Fraleys with a quite comfortable way of life. Sometime in the middle '50s J P had entered a local fiddle contest on a whim and won it, much to his surprise as he was utterly out of practice (J P spins the tale hilariously on our NAT website). Pretty soon a guitarist named Hubert Rogers asked him if he wanted to form a square dance ensemble for the dances across the river in Ironton, Ohio. Soon thereafter the group asked Annadeene to sing country-western songs for the round dance interludes. Hubert Rogers had had prior dealings with Jean Thomas and that is how the Fraleys came to meet her in the early '60s.

Thomas immediately recognized that Annadeene was extremely intelligent and could aid her faltering 'pageant' considerably. Annadeene soon found herself engaged with a large portion of the festival's logistics in addition to appearing on its program. Quite tellingly, Annadeene once indicated that the best part of her time with Thomas (who could otherwise be a difficult boss) came from listening to the somewhat salacious stories Jean would tell about her early days, when she worked in Hollywood as a script girl and as a publicist for the notorious speakeasy hostess Texas Guinan (the contrast between the secret Jean Thomas and the prim old lady clothed in 'linsey-woolsey' always amused Annadeene). These entanglements with Thomas didn't last long (Annadeene once remarked that 'she began interfering in our marriage') but Annadeene gained a lot of experience in how to run and publicize a music festival.

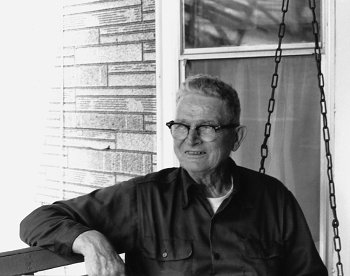

As it happens, for some time a small annual Fraley family reunion had been held in one of the state parks and J P and Annadeene were invited to enlarge this into a more public occasion, following the informal model that their friends Nancy McLellan and Barbara Kunkle adopted in their Mountain Heritage Festival over at the college in Ashland (in contrast to Thomas' tightly scripted rigamarole). By this time, the Fraleys had shifted to entertaining within the little restaurants associated with the parks rather than mainly at square dances and had developed an easygoing stage presence along the way. Gradually, the Fraley Festival became a late summer attraction for folks in the middle South who were beginning to become interested in their local heritage again. Ray Hilt represents an excellent case in point: as we noted in volume 1, he had loved the fiddle growing up on an isolated farm across the river in Ohio, but had laid the instrument aside after World War II when he moved north to Marion and worked in the feed business. After he retired in the 1980s, he and his wife liked to travel about in a camper and one summer they dropped by the Fraley Festival on a whim. Its relaxed and welcoming atmosphere inspired Ray to pick up the fiddle again. Roger Cooper and Buddy Thomas had both worked in a tire factory near Marion in the early '70s and Roger was surprised that he hadn't run into Ray back then. But the reason was simple: Ray was working at the time and wouldn't have found the world of barroom bluegrass playing especially amenable to his old-fashioned, gentler style. In fact, it is partially because of welcoming forums like the Fraley Festival that John Harrod and I found it somewhat easier to locate old time fiddlers in the 1990s than in the 1970s, despite the fact that their numbers had plainly decreased (the fact that many former Kentuckians had returned to their home state after leaving in the postwar period also helped).

As I observed earlier, I don't believe that such festivals provide as an attractive arena for traditional mountain singing as for fiddling and instrumentally-supported singers such as the Yorks (performing in a group is less conducive to stage fright, inter alia). Insofar as unaccompanied songs did get performed on festival stages, they were frequently executed in the melodramatic manner of the revivalists ('a capella ballad singing', they would call it), rather than the unmannered narrative of most traditional singing. Accordingly, a homespun singer who had wandered into such proceedings would be far less likely to suppose as Ray Hilt did, "Why, I can do that too". Accordingly, although an undramatized singer such as Mary Lozier would occasionally sing a ballad or hymn at a folk festival, the locale never provided a wholly satisfactory functional replacement for the music's former 'home entertainment' venue. Sometimes Annadeene herself would sing an unaccompanied song or two (she had learned Rare Willie Drowned in Yarrow from Almeda Riddle when they worked together at the Knoxville World's Fair) but I generally liked these performances least, as they seemed slightly reminiscent of dressing in 'linsey-woolsey.'

Although Annadeene found a comfortable place within the world of modern folk festivals, I believe that, in her heart, she secretly found some of their representations a bit artificial. We were preparing to take the pictures for the Maysville album cover when Annadeene emerged clothed in one of the 'granny dress' costumes that she generally wore for her festival appearances. I asked, "Gee, Annadeene, you're a handsome woman. Wouldn't you rather look sharp in your best Sunday clothes?" She told me later that she was flattered by that suggestion, for she truly preferred being taken for what she was: a smart, good-looking and up-to-date woman. And so that is the way I wish to present her here.

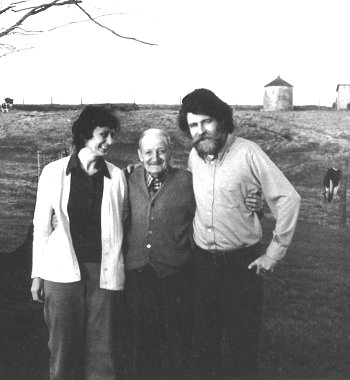

The way that Gus and I happened to meet the Fraleys is this. J P had begun traveling to some of the fiddler's contests that were gradually rejuvenating around the South; in particular, to Harper Van Hoy's pleasant arrangements in Union Grove, North Carolina. Gus met J P there and subsequently invited the Fraleys to perform for the Greater Washington Folklore Society. After we began our work on Asa Martin's record in 1972, Gus suggested that we approach the Fraleys and so I met them on our second trip to Kentucky. Although Gus and I had both listened to a lot of fiddle music in one context or another, neither one of us had much familiarity with the tunes native to J P's local context (beguiled by irrelevant political boundaries, we instead expected to hear strains akin to those formerly found in southeastern Kentucky, quite a different kettle of fish insofar as fiddle tunes go). In fact, the airs native to the Ohio River basin were melodically more complex than their southern counterparts and were bowed in altogether different fashion. In any case, although J P had picked up a fair measure of these local melodies through natural osmosis, much of his active repertory consisted in tunes derived from Big Howdy Forrester, Kenny Baker and other prominent Nashville fiddlers (J P often couldn't recollect origins, for many of his tunes had been absorbed in jam sessions at the festivals and contests he would frequently attend).

But these standard tunes were of little use to Gus and me, for to make a record that would impress our intended audience, the selections needed to be fresh and to reflect the local region. And there was a second factor that complicated the planning of a fiddle record. By this time, square dancing playing had dramatically decreased in Kentucky, as the dance's remaining clientele began its weird drift towards fancy outfits and prerecorded versions of World War II era popular songs. But their functional replacements as a fiddler's audience, the folks who attended the folk festivals, most warmly applauded the stock 'show stoppers' familiar from radio and television. In truth, when the top 'radio fiddlers' got together amongst themselves, they would often draw forth the older tunes, because they knew they were both prettier and more difficult of execution. But the conviction that no one else wished to hear these old melodies became deeply rooted amongst most public performers, which is why so many fiddle LPs of the period display such a limited palette of tunes. Such presumptions Gus and I worked hard to reverse; eventually with some success, I believe. But in the short run our policies led to some misapprehensions, as J P struggled to satisfy our demands in the face of worries that he should perhaps be recording something else.

For example, he played a perfectly lovely piece called Cluckin' Hen (Rdr 0037) that, in retrospect, must have been derived from Howdy Forrester, although considerably transmogrified through J P's individualistic style. As such, it represented a rare and perfectly traditional tune, although one that reflects Forrester's Dickson County, Tennessee heritage rather than J P's own. However, J P credited the tune instead to Ed Haley, whom he had often heard on Ashland's streets as a young boy. I now believe that this mistaken accreditation arose through the following process. There were once several tunes involving both hens and left hand pizzicato native to J P's region, one of which he probably did hear as a young man. However, the intervening years where his fiddling lay fallow and then the emergent pungency of the Forrester setting effectively ruined J P's ability to recall his boyhood tune accurately. Under the pressure of our crude entreaties, however, he imagined that he did. J P's performance remains absolutely first class, but it is a pity that its origins were probably misidentified, for one of our scholarly ambitions had been to pin rare tunes to particular regions, in the hope that we might be able to trace historical patterns of fiddle tune transmission thereby. The reader interested in such reconstructive projects should be warned that much published data on fiddle tune 'origins' has been corrupted by similar processes.

In fact, for some years after, J P was somewhat unhappy that the resulting LP didn't 'really show his fiddle style', meaning that it didn't adequately demonstrate his capacity to perform the modern tunes capably. In later years, he changed his mind somewhat, as he gradually realized that it was precisely the uniqueness of his local tunes that served as the magnet that slowly began to attract outsiders to the region (Annadeene, in fact, was more prescient about these matters than J P). Today a fiddler like Roger Cooper is heartened by the fact that young Kentuckians like Michael Garvin are beginning to take pride in their local heritage and play some of the old tunes again, but it took some years of gentle weaning to create such an opening.

No doubt the moralizing critics of whom I complained earlier will find these revelations appalling. 'Surely, the folklorist should record everything in an artist's repertory with the strictest neutrality, capturing exactly their own preferences at that moment in time'. Yes, but precisely whom did they imagine was likely to fund or fulfill this perfect research project? I detected no academic folklorist laboring in our pastures throughout my entire involvement with Kentucky's music. Moreover, it cost us (and Rounder) a sizeable amount of money in terms of equipment and travel to record the material we did; the ideally complete survey was utterly beyond our financial capacity. In light of those limitations, focusing upon the most fragile local materials seemed the only prudent policy. Finally, and most importantly, why would such critics presume that any informant would have wished to endure the brutal ordeal of sitting before the tape recorder that a 'complete survey' would have demanded? J P and Annadeene were the most genial hosts possible, but I doubt that either would have tolerated such a grueling schedule 'for the sake of pure scholarship' (their daily lives were simply too busy to allow that luxury).

I have always been thankful that, courtesy of Rounder's underwriting, we could offer most of our performers the assurance that some of their material would appear on records under their own names for honest royalties (unfortunately, through factors beyond our control, it sometimes took much longer to complete those projects than we ever anticipated). By the same token, I have been dumbfounded by the streams of revivalists who have persuaded themselves, under the veil of Southern politeness, that country musicians are likely to feel honored to have been visited by urban youth who then publish these tunes on their - that is, the urban performer's - records. Well, I have never met a fiddler who didn't think better of his or her own musicianship than that! Again, being able to offer a Rounder recording contract proved the optimal emollient to assuage the abrasions of visitors who were often mistrusted as urban exploiters otherwise (the youth who visited the state in search of fiddle tunes rarely conceived of themselves as part of the commercially successful 'folk music' boom visible on television but our Kentuckians rarely drew such distinctions).

However, in Annadeene's case, I could not offer any parallel opportunity so I tried to explain the basic situation to her as honestly as I could. These rather awkward initial discussions eventually opened out into an intellectual framework whereupon we could compare astringent notes on how the weird world of record companies, folk festivals and urban revivalists worked. In particular, I think that we both enjoyed learning the point of view of someone who had been brought up on the other side of the urban/country divide. And once we got started on the right foot together, Annadeene took equal pleasure in tracking down rural performers who still retained the purest cadences of old-time Kentucky in their songs and speech. Like Rev Kazee, she wanted to lead a successful modern life without pretending to be anything other than what she was, but she fully appreciated the pioneer generations who had come before. I am very pleased that on these CDs I can finally feature those parts of Annadeene's own repertory that stand closest to Kentucky's traditions; I only wish I had found a greater opportunity to do so before she died.

Operating as an unpaid intermediary between a traditional performer and a faraway record company was not always easy, but I wouldn't have traded those inconveniences for any other arrangement. There were many who threw themselves at the feet of their informants with nothing more than a "Oh, tell us of your wisdom, noble mountaineer", having no more tangible rewards to offer. Some performers, of course, happily succumbed to such blandishments, often becoming tautologous bores in the process, but keener observers such as Annadeene spied the falseness of the posture right away. There was no reason why a university professor should really wish to take one-sided lectures from her and she knew it.

To briefly finish up the chronology of our interactions, my own visits to Kentucky halted in late 1974. Some of this was due to my taking a far away teaching job and having little money, but part of it was the result of my having endured a messy divorce in that period. Annadeene was a deeply religious person and I dreaded explaining my circumstances to her (in this expectation, I was naive, for when we talked about these problems years later, she was completely understanding, having been tutored in the awkward complications of modern life as fully as myself). In 1994, J P ran into Rounder's Ken Irwin at some folk event and Ken asked J P if he would be interested in doing another record. J P replied, “Well, would Mark Wilson be available to do it?” I hadn't been involved in much record work for a considerable time, but I happened to have just moved to Columbus, Ohio and so it was comparatively easy to drive down to the Fraleys' house (starting this project prompted me to contact John Harrod to begin our collaborations). In the course of working on a fiddle CD (Maysville, Rdr 0351), I realized that I had assembled enough material to construct an album of children's songs (The Land of Yahoo, Rdr 8041) and that I could also utilize some of the song material that J P and Annadeene knew in this context. That all went well and the Fraleys then commissioned me to record material of Annadeene's own choosing for a privately issued cassette, Another Side of the Fraleys (Road's End 001). It is from these final sessions that Annadeene's songs on these CDs have been drawn. By this time, her cancer treatments had slightly coarsened her voice, but the recordings still provided a good representation of the songs she liked to sing. I told her that one day I would like to blend her traditional material together with some of the field tapes that we jointly recorded and this collection represents the fulfilment of that promise.

I hope these rambling recollections provide some insight into the factors that constrain any preservational project of this sort and provide some counterweight to the methodological critics who never think about the human and economic dimensions of such concerns. And I also want these memories of Annadeene's contributions to serve as an indirect means for thanking all the other fine Kentuckians who have aided our collecting work over the years in ways large and small. It would be impossible to cite them all, but I will especially cite Roger Cooper (who has as often served as my recording companion in my later work as Annadeene did before), Nancy McLellan (who came along on many of the early trips), the late Buddy Thomas, Barbara Kunkle, Mary Meade, Wally Wallingford and Gary Cornett (a fuller list is provided in the credits). I also thank Bill Nowlin and Rounder Records for their logistic support without which our NAT work would have proved impossible.

Volume 3: I'll Have a New Life

As I began to plot out this portion of our program, an underlying theme emerged on its own accord, without premeditation on my part. Many of the songs on this CD strike me as revolving, in one fashion or other, about the dilemma that philosophers call 'the problem of evil': how can it be that an omniscient and benevolent God tolerates so much undeserved suffering in the world and permits the oppression of the virtuous poor by the callous rich? Of course, every Christian society has mediated deeply on these matters and the divisions between sects frequently turn upon how they resolve these issues. American folk tradition, its black and white populations working in complicated crossover, has often managed to epitomize these concerns musically in a most poignant manner. As such, this CD is not a collection of 'religious songs' exactly, but reaches into the penumbra of compositions like East Bound Train or Little Bessie that lie near them.

1. Farther Along - The Dixon Sisters, vocals (Rec: Mark Wilson, Roger Cooper and Wally Wallingford, Salt Lick, Ky, Fall, 2002). Roud 18084. This classic nineteenth century hymn encapsulates our thematic tensions in an admirably direct fashion. Beautifully sung by the Dixons here, I've never located a reliable attribution of authorship for either words or tune.

Tempted and tried we're oft made to wonder

Why it should be thus all the day long?

While there are others living about us

Never molested, though in the wrong.

Chorus: Farther along we'll know all about it

Farther along we'll understand why.

Cheer up, my brother, live in the sunshine

We'll understand it all bye and bye.

When death has come and taken our loved ones

It leaves our homes so lonely and drear.

Then do we wonder why others prosper

Living so wicked year after year.

When we see Jesus coming in glory

When he comes from his home in the sky,

Then we shall meet him in that bright mansion

We'll understand it all bye and bye.

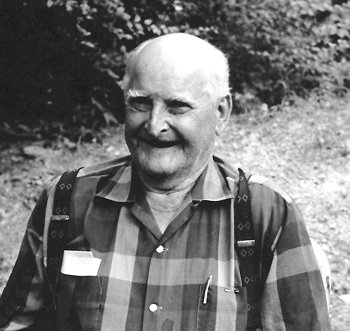

2. Little Bessie - Buell Kazee, vocal and banjo (Rec: Mark Wilson, Winchester, Ky, Fall, 1972). Roud 4778. Gus Meade's discography attributes this piece to R S Crandall and the music was apparently published in 1868 (according to a listing of sheet music I found on the web). Crandall seemed to have been a prolific composer of songs in this vein, including Little Blossom which occasionally shows up in tradition as well. Despite its length, Little Bessie has firmly incorporated itself into the Regular Baptist song corpus and Mary Lozier, Sarah Gunning and Nimrod Workman each provided me with fine versions of the song (Roscoe Holcomb has also recorded it on Fwys 02368). Rev Kazee supplied one of its earliest recordings, for Brunswick in 1928, although he was forced to compress its verses to suit the three minute format. The song has been recorded many times since and it remains popular in bluegrass circles today. Kazee's affecting performance here reveals why so many traditional singers have held this song dear to their hearts, for its verses speak directly to the dreadful sufferings occasioned by the childhood deaths that commonly afflicted so many country families. Sarah once commented to me about another well known folk song that describes the terrors of the same tuberculosis that ravaged her own family:

When I used to sing that 'Lonesome Dove' and I came to the part where it says:

Death, grim Death, did not stop there

I had a babe, to me most dear

Death, like a vulture, came again

And took from me my little Jane

my friends expected me to sing 'James', for that was the name of my little baby who died just like in the song.

Perhaps such songs provided comfort in reassuring Appalachian families that some wider, objective order must lie behind their particularized sufferings. Certainly, Rev Kazee's beautifully nuanced shadings in this performance embody a good deal of complex thought on these matters. For fascinating glimpses into some of Buell's theological opinions, consult Loyal Jones' Faith and Meaning in the Southern Highlands.

“Hug me closer, closer, Mother

Put your arms around me tight,

For I'm cold and tired, Mother

Oh, how strange I feel tonight.”

“Something hurts me here, dear Mother

“Something hurts me here, dear Mother

Like a stone upon my breast,

And I wonder, wonder, Mother

Why it is I cannot rest.”

“Just before the lamps were lighted

Just before the children came,

While the room was very quiet

I heard someone call my name.”

“But I could not see the Savior

Though I strained my eyes to see.

And I wondered if He saw me

Would He speak to such as me?”

“All at once the window opened

One so bright upon me smiled

And I knew it must be Jesus

When He said, 'Come here, my child'.”

“Come up here, my little Bessie

Come up here and live with Me.

Where the children never suffer

Suffer through eternity.”

“Then I thought of all you've told me

Of that bright and happy land,

I was going when you called me

When you came and kissed my hand.”

“Hug me closer, closer, Mother

Put your arms around me tight,

Oh, how much I love you, Mother

And how strong I feel tonight.”

And the mother hugged her closer

To her own dear burdened breast,

On the heart so near its breaking

Lay the heart so near its rest.

At the solemn hour of midnight

In the darkness calm and deep,

Lying on her mother's bosom

Little Bessie fell asleep.

3. Wandering Boy - Sarah Gunning, vocal (Rec: Mark Wilson, Medford, Ma, 5/9/74). Roud 4227. This often recorded number was composed by the Rev Robert Lowry in 1877 as Where is my Wandering Boy Tonight? Lowry was well educated and the pastor of a large Baptist congregation in Plainfield, New Jersey. He edited many of the popular Baptist hymnals of the late nineteenth century, as well as composing favorites such as Shall We Gather at the River? Lowry left an interesting account of his compositional procedures:

I have no method. Sometimes the music comes and the words follow, fitted insensibly to the melody. I watch my moods, and whenever anything good strikes me, whether words or music, and no matter where I am, at home or on the street, I jot it down ... My brain is a sort of spinning machine, I think, for there is music running through it all of the time. I do not pick out my music on the keys of an instrument, the tunes of nearly all the hymns I have written have been completed on paper before I tried them on the organ. (J H Hall, Biography of Gospel Song and Hymn Writers)

Lowry's original lyrics are rather different from those found in tradition. Indeed, the song has itself wandered greatly in its journey from Lowry's original sensibilities to the great emotional investment that rural singers like Sarah Gunning pour into the song. The Carter Family recorded a celebrated version with a different opening verse; it remains quite popular with bluegrass gospel groups (Ralph Stanley, Dave Evans). The Wandering Boy that Roscoe Holcomb loved (Fwys 2326) is a different song, drawn (I believe) from the Sweet Songster tradition.

Chorus: Bring back to me my wandering boy

There is no other left to give me joy

Tell him his mother with faded cheeks and hair

In the old home will welcome him there.

Hun 'til you find him and bring him back to me

He is my boy wherever he may be

Although he has wandered in darkness and in sin

Bring him back to me and I'll welcome him in.

Out in the hallway there stands a vacant chair

Yonder is the shoes my boy used to wear

Empty the cradle, the one he loved so well

Oh, how I miss him, there's no tongue can tell.

Well I remember the parting words he said

“Meet me up there where no tears will be shed.

There'll be no goodbyes in that bright home so fair

When life is over, I'll meet you up there.”

4. The East Bound Train - The Dixon Sisters, vocals (Rec: Mark Wilson, Roger Cooper and Wally Wallingford, Salt Lick, Ky, Fall, 2002). Roud 7390. Gussie Davis' popular In the Baggage Coach Ahead encouraged a cycle of similarly themed compositions during the late Victorian era, including this fondly remembered 1896 production by James Thornton and Clara Hauenschild (published as Going for a Pardon). Like other traditional versions, the Dixon's text neglects to tell us whether the old, blind father received his pardon or not (he did); the song gains, I think, from concluding where it does. Norm Cohen's Long Steel Rail has an excellent chapter on this entire family of songs and correctly observes that the shared truncations of East Bound Train most likely trace to the emendations of some single, intervening performer. It is worth observing that the same basic phenomenon - considerable divergence from printed sources yet great commonality in the 'folk' variants - occurs many times over in American traditional music, amongst its fiddle and banjo tunes as well as its ballads. And the basic explanation must be the same: some undocumented chain of communication from some intermediate nodal source has spawned the 'folk' versions.

The east bound train was crowded, one cold December day

The conductor shouted, “Tickets!” in the old-time fashioned way.

A little girl with sadness, her hair was bright as gold

She said, “I have no ticket” and then her story told.

“My father, he's in prison; he's lost his sight they say

I'm going for his pardon, this cold December day.

My mother, she is sewing to pass the time away

But, my poor old blind father, he's in prison and he's there to stay.”

The conductor said, “God bless you, little one, just stay right where you are.

You'll never need a ticket as long as I'm on this car.”

5. I Know Somebody's Going to Miss Me When I'm Gone - Perry Riley, vocal (Rec: Mark Wilson, A Fraley and B Thomas, Hayes Corners, Ky, 8/29/73). Perry Riley was Buddy Thomas' cousin and a fine country fiddler in his own right (an instrumental performance appears on volume 4 and several more can be found on Rdr 0376). All his life he had wandered the South in search of work, living at different times in West Virginia and Arkansas. The day we met him, he had injured himself in an accident and was waiting for a bus to convey him to an old folks' home, where he died not long after. Despite all this, he was very animated and cheery that day. After we had recorded a number of wonderful fiddle tunes, he asked if he could sing a few selections, including this one, of which he stated proudly, “I composed that one myself.” Indeed, though undoubtedly based upon some preexistent prototype, I am not familiar with anything quite like this (beyond distant similarities to the Carter Family's Will You Miss Me When I'm Gone?). These many years later, I can still vividly see Perry listening to the playback of this number on the headphones and smiling broadly at the results as I packed the rest of my equipment into the car (we were very late to a dinner engagement with one of Buddy's sisters).

Not so long ago one morning, Mother called me to her bed

And she threw her arms all around me, “Listen to these words”, she said.

“Son, I'm going to leave you but you won't be left alone

If you put your trust in Jesus after He has carried me home.”

Chorus: It won't be very long before I get to go see my mother, she's went on.

I know somebody's going to miss me

I know somebody's going to miss me when I'm gone

I know somebody's going to miss me when I'm gone.

When my life on earth is ended and they lay me beneath the sod

I expect to meet my mother somewhere around the throne of God.

I never will forget that morning when they laid her beneath the sod

I thought my heart was breaking but I put my trust in God.

Ever since that fateful morning Christ has been my hopes every day

And I know sometime I'll be with him, I'll be with him there to stay.

6. Mother's Grave - Earl Barnes, vocal and guitar, with the Cumberland Rangers: Jim Gaskin, fiddle; Buz Brazeale, autoharp; Asa Martin, guitar (Rec: Mark Wilson and Gus Meade, Irvine, Ky, May, 1972). Previously issued on Rdr 0145. Earl is from Richmond, Kentucky and usually did not play with Asa's group, although they were all friends. One of the aggregation's regular members, Gilbert Thomas, had a bank job that unfortunately prevented him from making most of our sessions, so Asa asked Earl to fill in instead. Normally, Earl sang with his own bluegrass band, the Bluegrass Travelers, which specialized in 'heart songs' like this. Almost certainly, he learned this song from the Starday recording by Bill Clifton and Dixie Mountain Boys, later reissued on Rounder 1021. An interesting figure who was perched halfway between country music and the folk revival, Clifton played a large role in enlarging the early bluegrass repertory with songs like this, whose ultimate origins I do not know.

When you kneel at Mother's grave in some lonely old churchyard

To place a wreath of flowers on her grave,

Won't you linger for a prayer and then ask to meet her there

In that land where we'll find peace and happiness?

Chorus: When you kneel at mother's grave

Thank her for the love she gave

And then tell her how much you miss her

When you kneel at your dear old mother's grave.

When you kneel at mother's grave, never try to hide your tears

For many are the ones she shed for you

And now that she's asleep, don't be ashamed to weep

For there'll be another quite so true.

7. Darling Little Joe - Blanche Coldiron, vocal and banjo (Rec: Mark Wilson, Heathen Ridge, Ky, 7/03/99). Roud 3545. Meade's discography cites two early claimants: V E Marsten, 1866 and C E Addison, 1876. The song was recorded fairly often, by the Carter Family, Bradley Kincaid, Mac Wiseman and others. However, probably the version that had the largest influence was Cousin Emmy's, who often sang it on her popular St Louis radio show (three remarkable airshots of Emmy playing the tune can be found on the Berea College website; they are far more lively than the rendition she later recorded for Folkways). Blanche learned this song from the radio; I imagine from Cousin Emmy, although I am not certain.. She certainly listened to Emmy, but she also credited other tunes to the radio broadcasts of Pa and Ma McCormick's ensemble (which made a single celebrated recording for Gennett as 'The Blue Ridge Mountaineers'). She especially admired their classical style banjoist, 'Bigfoot' Homer Castleman.

What will the birdies do, Mother, in the spring

Will they pick up the crumbs from around my door?

Will they hop from the trees and tap at my window

And ask why Joe wanders out no more?

What will the kitten do, Mother, all alone

What will the kitten do, Mother, all alone

Will he stop his frolic for a day?

Will he lie on the rug beside of my bed

As he did before I went away?

What will Thomas, the old gardener, say

When you ask him for a flower for me?

Will he give you a rose he has tended with care

Fairest first bloom of the tree?

I could see tears in his honest old eyes

He said the wind had brought them there

As he gazed on that cheek growing paler each day

His hand it trembled o'er my hair.

Keep Tag, Mother, my poor little dog

I know he'll mourn for me too.

Lying around in the shade of a tree

Mourning the long hot summer through.

Show him my coat so he won't forget

His master who will then be dead

Speak to him kindly and ask him of Joe

And pat him on his brown shaggy head.

And you, dearest Mother, will miss me for awhile

But in heaven no larger I'll grow

Any kind angel at the gates will know

When you ask for your darling little Joe.

8. The Evening Train - Annadeene Fraley, vocal and guitar; J P Fraley, fiddle; Doug Chaffin, bass (Rec: Mark Wilson, Denton, Ky, December, 1995). Previously issued on Road's End 001. This song derives from a 1949 recording by Molly O'Day (Co 20601), written by Hank and Audrey Williams. It seems plainly constructed as a follow up to Molly's earlier A Hero's Death, itself a recasting of a parlor ballad from 1899: He's Coming to Us Dead, written by Gussie Davis, whose earlier In the Baggage Coach Ahead had initiated, we have already noted, the extensive 'misery on a train' binge within late Victorian popular song. Annadeene recalled being troubled by an overdubbed baby's crying on Molly's original record, although she had, in fact, confused The Evening Train with Molly's Don't Sell Daddy Any More Whiskey in this regard.

While on the topic of Molly O'Day, I would like to mention, with fond remembrance, the 1974 visit that Gus Meade and I paid to Molly and Lynn Davis' home in Huntington to interview them both about the fiddler Ed Haley (I had already spoken to her brother Skeets at length on the telephone). Molly was a woman consumed with religion and Gus and I were struck by the allied spiritual depths that she attributed to Uncle Ed's fiddle music. A few years later, after the LP we edited of Haley home recordings was finally released, Molly wrote Marian Leighton at Rounder Records that 'the music must have come down from heaven'. Molly also told me of how much balladry could still be heard around her original home in McVeigh, Kentucky and, in one of the most privileged moments of my musical life, sat me down in a corner and sang me an utterly exquisite Lady Gay, with a text and melody much like Buell Kazee's. Unfortunately, that was my last visit to the region for many years and so I was unable to follow up on Molly's leads. If I had, I might have met Snake Chapman twenty years sooner.

While on the topic of Molly O'Day, I would like to mention, with fond remembrance, the 1974 visit that Gus Meade and I paid to Molly and Lynn Davis' home in Huntington to interview them both about the fiddler Ed Haley (I had already spoken to her brother Skeets at length on the telephone). Molly was a woman consumed with religion and Gus and I were struck by the allied spiritual depths that she attributed to Uncle Ed's fiddle music. A few years later, after the LP we edited of Haley home recordings was finally released, Molly wrote Marian Leighton at Rounder Records that 'the music must have come down from heaven'. Molly also told me of how much balladry could still be heard around her original home in McVeigh, Kentucky and, in one of the most privileged moments of my musical life, sat me down in a corner and sang me an utterly exquisite Lady Gay, with a text and melody much like Buell Kazee's. Unfortunately, that was my last visit to the region for many years and so I was unable to follow up on Molly's leads. If I had, I might have met Snake Chapman twenty years sooner.

I heard the laughter at the station

But my tears fell like the rain.

When I saw them place the long white casket

In the baggage coach on the evening train.

The baby's eyes are red from weeping

Its little heart is filled with pain.

Oh, Daddy cried, “They're taking Mama

Away from us on the evening train.”

As I turned to walk away from the depot

It seemed I heard her call my name

“Take care of baby and tell him, darling

That I'm going home on the evening train.”

I hope that I will have the courage

To carry on my life again

But it's hard to know she's gone forever

They're carrying her home on the evening train.

Repeat first verse.

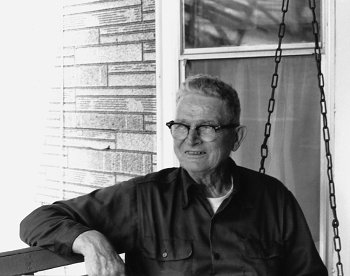

9. The Day has Passed and Gone - Wash Nelson, vocal (Rec: Mark Wilson, Annadeene Fraley and Mary Nelson, Ashland, Ky, May, 1973). “I learned that when I was three years old”, Wash told us. “I don't forget bad.” And he was right: at ninety-three his memory was very impressive. Apparently, his ability to remember complex songs and texts at a young age gained him some local notoriety as a 'child preacher'. The tune is usually called Evening Shade and is found as such in William Walker's celebrated Southern Harmony. and elsewhere. A beautiful lined out version by the Indian Bottom Regular Baptist church can be heard on one (SF 40106) of the two important Smithsonian-Folkways CD collections that have been recorded by Jeff Titon. Titon reports that E D Thomas' Hymns and Spiritual Songs (usually called 'The Thomas Hymnal' by my informants) credits our text to John Leland, 1804, whereas E W Billups' The Sweet Songster consigns it to one 'Dupuy'. These two books are the most important sources and unifiers of tradition in our section of Kentucky, but I unfortunately don't have direct access to either one. Both tended to be printed and peddled quite locally within our region (the Thomas collection was first published in 1877 by a Regular Baptist pastor from Danville, Indiana whereas Billups published his collection in 1854 and lived in a number of locales along the Ohio River). Mary Lozier drew mainly upon The Sweet Songster as did Roscoe Holcomb (I believe), whereas Nimrod and the Garlands leaned more to the Thomas compilation (in fact, Sarah's religious repertory was very wide, ranging, as can be witnessed here, from the shape note repertory to Holiness shouts). The song itself is also common in black tradition, ranging from Watch That Star by the McIntosh County Shouters on Fwys FE 4344 to the eerie (and nearly unrecognizable) treatment by the Staple Singers on VeeJay. Wash includes two verses not included on the Indian Bottom recording.

The day has passed and gone, the evening shades appear

Oh, may we all remember well, the night of death draws near.

Now we'll lay our garments by, down on our beds to rest

But death may soon disrobe us all of what we now possess.

Lord, keep us safe this night, secure from all our fears

And angels guide us while we sleep 'til morning light appears.

But when we early rise and view the weary sun

May we set out to win the prize and after glory run.

But when our days are past and we from time removed

Oh, may we in the bosom rest, the bosom of our Lord.

10. Motherless Children - Roscoe Holcomb, vocal and banjo (Rec: Mark Wilson, Cambridge, Ma, Fall, 1972). Roud 16113. Gus Meade's discography credits this to a turn of the century publication by S C Brown and Charles Dryscoll; this copyright claim presumably represents the reason why the song was omitted from the republication of Randolph's Ozark Folk Songs by a nervous publisher.  I've never seen the sheet music Gus cites, but I would predict that it merely represents a reworking of a traditional form as heard here, for the piece's appearances are too varied and widespread to explain easily otherwise. Of these, Blind Willie Johnson's performance on Co 14343 is particularly well-known, but the Carter Family's quite different performance on Vi 23641 can't be far behind. Roscoe performs this song on guitar on SF 40104; his fingering technique there is essentially borrowed from the thumb lead banjo styling employed here.

I've never seen the sheet music Gus cites, but I would predict that it merely represents a reworking of a traditional form as heard here, for the piece's appearances are too varied and widespread to explain easily otherwise. Of these, Blind Willie Johnson's performance on Co 14343 is particularly well-known, but the Carter Family's quite different performance on Vi 23641 can't be far behind. Roscoe performs this song on guitar on SF 40104; his fingering technique there is essentially borrowed from the thumb lead banjo styling employed here.

Reliably tracing the histories of older gospel songs is difficult, due, inter alia, to the longstanding practice of altering older songs slightly to obtain copyright advantage or other purpose. This has particularly occurred with the evocative folk spirituals of the nineteenth century. For example, the Dixon Sisters sang me the venerable By and By, I'm Going to See the King (as recorded by Washington Phillips and others) as a more diffuse Soon and Very Soon. The latter represents a 1970s recasting by a celebrated black evangelist from Southern California named Andrae Crouch. The enormous popularity of his new setting has now effectively eradicated most memories of the original song.

It's motherless children sees a hard time when their mother is dead and gone (x2)

They get hungry, they get cold, they go begging from door to door

It's motherless children sees a hard time when their mother is dead and gone.

It's father will do the best he can when the mother is dead and gone (x2)

Father will do the best he can, but he really don't understand

It's motherless children sees a hard time when their mother is dead and gone.

It's sister will do the best he can when the mother is dead and gone (x2)

Sister will do the best she can, but she really don't understand

It's motherless children sees a hard time when their mother is dead and gone.

It's brother will do the best he can when the mother is dead and gone (x2)

Brother will do the best he can, but he really don't understand

It's motherless children sees a hard time when their mother is dead and gone.

11. In a Foreign Heathen Country - Sarah Gunning, vocal (Rec: Mark Wilson, Medford, Ma, 5/08/74). Roud 16775. This is Sarah's family's title; someone later told her that its proper name was A Call to Arms. According to Gus Meade, however, this Pentecostal piece was, in fact, composed by John B Goins in 1907 as Called to Foreign Fields, and first published in Songs of Pentecostal Power. Alfred G Karnes supplied a very vigorous performance with harp guitar under that title for Victor (reissued on Dust to Digital 01 or Yazoo 2200; Roy Harvey also recorded the number). The song vividly captures the sense of wrenching dislocation that is frequently encountered within the memoirs of nineteenth century missionaries. I found mention of a 'John B Goins' associated with a Pentecostal church in Cleveland; perhaps this is where the composer resided (although he was apparently forced to leave the locale after a theological dispute over the merits of speaking in tongues).

In a foreign heathen country where the people know not God

I am going there to preach His precious word.

Where they bow to worship idols I am going there to stay

For to labor in the vineyard of my Lord.

Chorus: Oh, I'll soon be with my loved ones in my happy heavenly home

Even though the thought my soul with rapture thrills.

So goodbye, my friends and brethren, for my time has come to go

I must leave you on the dear old battlefield.

Many days I've clim'd the hillside, in the sunshine and the rain

Many days I've been in hunger and in thirst.

Just to tell them my Lord is coming back to earth again

With his my gifts and blessings always at the first.

I was called to bear a message to the heathen far away

Even though there a stranger I may roam

Just to tell them that my Lord is coming back to earth again

That's the reason that I left my native home.

12. Robinson Crusoe - Jim Garland and Sarah Gunning, vocals (Rec: Mark Wilson Medford, Ma, 5/07/74). Here is a true curiosity, for it represents a condensed version of William Cowper's poem of 1782, The Solitude of Alexander Selkirk, the real life prototype of Defoe's hero. How it came into the Garland family is unknown to me. Some of Cowper's texts were set to hymn tunes and so it is quite possible that this setting appeared within one of the shape note hymnals published for the singing schools. However, the poem commonly appeared in popular anthologies such as Palgrave's celebrated Golden Treasury. It is a myth to presume that mountain folk, even within a vicinity as remote as the Garland family's Bell County, ever stood entirely isolated from popular literature. Indeed, I recorded a remarkable folk tale from Jim called The Land of Yahoe (Rdr 8041) which draws upon the Land of Cockaigne fable and alludes to elements of both Gulliver's Travels and The Arabian Nights (Aunt Molly Jackson recorded a version for the Library of Congress, also learned from Jim's mother, that I've never heard; it would be curious to observe the elements she has included in the story). Moreover, Jim had also acquired from one of his brothers an amazing limerick that entangles President James Buchanan, Queen Victoria and the first laying of the transatlantic cable in sexual metaphor, an odd artifact that reflects an appreciable awareness of far away current events within old-time Bell County.

Around and around by the sea

I must finish my journey alone

Never again to hear the sweet music of speech

I start at the sound of my own.

Around and around by the sea

My rights there are none to dispute

From the center around to the sea

I am lord of the fowl and the brute.

The sea fowl has gone to her nest

And the beast they lay down on the lair

And man must be content with his lot

Now I to my cabin repair.

Repeat verse one.

13. The Unclouded Day - J P Fraley, fiddle (Rec: Mark Wilson, Denton, Ky, 3/07/99). Roud 17614. In volume 2 we observed the once common Kentucky practice of playing ballad tunes as slow airs on the fiddle. Performing hymn tunes was even more common and some churches, particularly the Holiness sects, positively encouraged it (J P tells a hair raising tale of being invited to play at a country church that proved to be a snake handling cult when he got there). However, choosing J P to represent this tradition here is a bit anomalous, for Annadeene was a devout member of a local Jehovah's Witnesses church. Most churches of this denomination frown upon any kind of music, but Annadeene's branch tolerated musical performance as long as it provided no representation of any religious topic (for the same reasons as the church forbids the celebration of Christmas). Although Annadeene and I discussed many things together, we generally avoided religion, in part because of my embarrassing ignorance of creed and in part because Annadeene was somewhat shy about talking of a church regarded as controversial even within her community (let alone by an uncomprehending academic such as myself). However, the evidences of her devotion were quite palpable, as she had many bookcases lined with church literature. I came to learn of her sect's unusual musical restrictions one day after she had requested a suitable 'English ballad' to learn for her festival. I had collected an unusual version of The Lady Gay out in Oregon that would have suited her voice perfectly, but she then informed me that, although she liked it, its reference to a heavenly 'King who might grant my boon' rendered it off-limits theologically.

I don't believe that J P himself officially joined the Witnesses, although his devoted and wonderfully supportive friends, Doug and Donna Chaffin, did. One day after Annadeene's death we were planning how to supplement the Fraleys' old Rounder LP Wild Rose of the Mountain with new selections for CD reissue, and decided that an unaccompanied cut might best bridge the gap between old and new. “Did your dad ever play hymns on the fiddle?” I asked. “Oh, sure, The Unclouded Day was his favorite tune.” “Well, how about that one?” I inquired, but J P hesitated, after many years of having conscientiously avoided religious material. After a bit of thought, he relented, although we wound up utilizing the setting of One Morning in May that he and Annadeene used to perform together instead. However, J P must have decided that he liked playing The Unclouded Day, for he recorded it as a duet with Betty Vornbrock on the Side by Side CD they recorded not long after our own session.

And well that J P should like it, as it surely represents one of our most evocative gospel pieces, composed by the Rev J K Alwood in 1882. My favorite rendering is that by Cliff Carlisle with his son Tommy (Decca 5716).

14. Keys to the Kingdom - Francis Gillum, vocal (Rec: Mark Wilson and Gus Meade, Isom, Ky, April, 1974). This fine gospel song saw a number of fine recordings on early 'race records' (Washington Phillips, Blind Willie Davis, Bessie Johnson) and there is a nice Library of Congress recording by Lillie Knox on Rdr 1831 that carries verses similar to Francis'. His impassioned performance here indicates the degree to which spirituals of this type represent a nineteenth century folk heritage shared by white and black Southern Baptists.

Oh, they called old John from the idols and put him in a kettle of oil

Oh, they called old John from the idols and put him in a kettle of oil

The Lord came down from heaven above, they tell me that the oil wouldn't boil.

Chorus: He had the keys to the kingdom and faith unlocked the door

He had the keys to the kingdom and the world couldn't do him any harm.

Go get your trumpet, Gabriel, and move down by the sea

And don't you blow that trumpet until you hear from me.

Oh, they put old Paul and Silas down in the jail below

While one did sing, the other did shout; the angel unlocked the door.

Oh Shadrac said Mishac, Mishac to Abednigo,

"The Lord's been good to us three boys, so count up the cost and let's go."

Oh, when you think you're living right and serving God every day

Just fall right down on your bended knees, He'll hear every word you say.

15. Little David, Play on Your Harp - Jim Garland and Sarah Gunning, vocals (Rec: Mark Wilson, Medford, Ma, 5/08/74). This fine call and response gospel number can be found in most of the standard collections (J and J Johnson, Book of Negro Spirituals; J Work, American Negro Songs). The Fisk University Jubilee Singers recorded a very early version and a gloriously wild version was recorded in the 1950's at a revival meeting in Whitesburg by Brother Claude Ely (King 1375). In a tamer setting, it seems to have recently become a campfire favorite at children's camps. Nimrod and his wife Molly supplied me with an excellent version as well, which I plan to include on a future reissue of Nimrod's Rounder LP (0076). Jim and Sarah's version is unusual in focusing upon Noah's travails rather than David's battle with Goliath.

Well, the Lord told Noahy (good Lord) for to build an ark (good Lord)

Out of gopher wood (good Lord) and gopher bark, good Lord.

Chorus: Little David, play on your harp, hallelu, hallelujah

Little David, play on your harp, hallelu.

Well, the Lord told Noahy (good Lord) just what to do (good Lord)

He began to saw (good Lord), and he began to hew, good Lord.

Well, it looks like rain (good Lord), oh, yes it might (good Lord)

Rain forty days (good Lord) and forty nights, good Lord.

Well, the water kept raising (good Lord) to the top of the house (good Lord)

Well, they opened up the windows (good Lord) and they all jumped out, good Lord.

16. I'll Have a New Life - John Lozier, harmonica (Rec: Mark Wilson and Roger Cooper, South Portsmouth, Ky, 9/26/99). This is a typical modern gospel product, written in the 1940s by Luther G Presley for the Stamps-Baxter syndicate. It was popularized by Hank Williams and John may have learned it from such a source.

16. I'll Have a New Life - John Lozier, harmonica (Rec: Mark Wilson and Roger Cooper, South Portsmouth, Ky, 9/26/99). This is a typical modern gospel product, written in the 1940s by Luther G Presley for the Stamps-Baxter syndicate. It was popularized by Hank Williams and John may have learned it from such a source.

17. While Passing a Garden - Mary Lozier, vocal (Rec: Mark Wilson and Roger Cooper, South Portsmouth, Ky, 9/26/99). I believe this song derives from Billups' Sweet Songster, although I can't verify it. Mary considered this to be her favorite song and commented:

I really like these old songs because they all have a story to tell and, no matter how long it takes to tell it, they take the time to do it.

G P Jackson cites an anonymous early version from oral tradition in The Northern Harmony. Most but not all of Mary's verses can also be found in the memoir of William Taylor, bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church for Africa, The Story of My Life of 1895, and I've also encountered passing quotations from it within diaries from the Civil War period.

While passing a garden, I paused for to hear

A voice faint and plaintive from one that was there.

The voice of the sufferer affected my heart

While in agony pleading the poor sinner's part.

In offering to heaven His pitying prayer

He spoke of the torments the sinner must bear

His life as arisen He offered to give

That sinners redeemed in glory might live.

I listened a moment and I turned me to see

What man of compassion this stranger could be

I saw Him low kneeling upon the cold ground

The loveliest Being that ever was found.

His mantel was wet with the dews of the night

His locks by pale moonbeams were glistening and bright

His eyes, bright as diamonds, to heaven were raised

While angels, in wonder, stood around him amazed.

So deep were His sorrows, so fervent His prayers

That down o'er his bosom ran sweat, blood and tears

I wept to behold him and I asked Him His name

He answered, 'It's Jesus, from heaven I came.'

'I am thy redeemer, for thee I must die

'The cup is most bitter but it cannot pass by

'Thy sins like a mountain are laid up on Me

'And all this deep anguish I suffer for thee.'

I heard with deep sorrow the tale of His woe

While tears like a fountain of waters did flow

The cause of His sorrows, to hear him repeat

Affected my heart and I fell at His feet.

Trembling with horror and loudly did cry

“Lord, save a poor sinner, oh, save, or I die.”

He smiled when He saw me and said to me, “Live.

Thy sins, which are many, I freely forgive.”

How sweet were the moments He bid me rejoice

His smiles, oh how pleasant, how cheering his voice.

I flew from the garden to shout it abroad

I shouted, “Salvation, and glory to God.”

I am now on my journey to mansions above

My soul's full of glory, of light, peace and love

I think of the garden, the prayer and the tears

Of that loving stranger who banished my fears.

The day of bright glory is rolling around

When Gabriel, descending, his trumpet shall sound

My soul then in rapture of glory shall rise

To gaze on that stranger with unclouded eyes.

18. In My Father's House - Henry Hurley, vocal and guitar (Rec: Mark Wilson and Annadeene Fraley, Flatwoods, Ky, May,1973). Roud 16172. This well known gospel song was recorded by the Carter Family as There'll be Joy, Joy, Joy, although their version does not include the father, mother, friends ... substitutions that Henry's version utilizes. Presumably, the lyrics allude to John 14:2.

Don't you want to go up there, up in my Father's house

Up in my Father's house, up in my Father's house

Don't you want to go up there, up in my Father's house

Oh, there's peace, peace, peace.

There'll be no drunkards there, up in my Father's house

Up in my Father's house, up in my Father's house

There'll be no drunkards there, up in my Father's house

Oh, there's peace, peace, peace.

We'll meet our friends up there, up in my Father's house

Up in my Father's house, up in my Father's house

We'll meet our friends up there, up in my Father's house

Oh, there's peace, peace, peace.

We'll meet our mothers there, up in my Father's house

Up in my Father's house, up in my Father's house

We'll meet our mothers there, up in my Father's house

Oh, there's peace, peace, peace.

We all be one up there, up in my Father's house

Up in my Father's house, up in my Father's house

We'll all be one up there, up in my Father's house

Oh, there's peace, peace, peace.

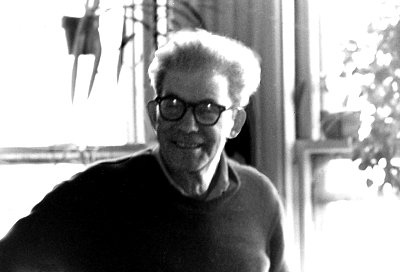

19. I'm Drinking from the Fountain - Nimrod and Mollie Workman, vocals (Rec: Mark Wilson and Ken Irwin, Chattaroy, WV, 3/03/76). Epstein's Sinful Tunes and Spirituals finds a Civil War mention of this while G P Jackson, in White and Negro Spirituals traces its refrain to a Revivalist Hymnal of 1872 from upstate New York. Early complete texts can be found as I've Just Come from the Fountain in Marsh's roughly contemporaneous (1880) The Story of the (Fisk) Jubilee Singers; it also appears in Work's later American Negro Songs. In my estimation, Jackson was unduly concerned to demonstrate the white antecedents of the well-known black spirituals and revival songs, for I'm sure that this very distinctive corpus of American song was forged in some very complicated crossover between the populations that defies ready summary, in the same fashion as our fiddle tunes were apparently framed. Incidently, I once recorded a violin piece with the title Just from the Fountain from Missouri's Art Galbraith (Rdr 0157). I don't detect any immediate melodic affinity, but Randolph had collected our hymn within Art's vicinity.

When we were recording, Nimrod asked his wife Molly to join in on several charming religious numbers and, as stated above, I hope to release more of these in the future.  On Nimrod's earlier LP (JA 0001), he had recorded similar duets with his daughter Phyllis. A few years later, Phyllis played the mother in the Loretta Lynn biography A Coal Miner's Daughter and Nimrod and banjoist Lee Sexton can be briefly glimpsed in that film as well.

On Nimrod's earlier LP (JA 0001), he had recorded similar duets with his daughter Phyllis. A few years later, Phyllis played the mother in the Loretta Lynn biography A Coal Miner's Daughter and Nimrod and banjoist Lee Sexton can be briefly glimpsed in that film as well.

Chorus: I'm drinking from the fountain, Lord (x3)