Article MT267

Note: place cursor on red asterisks for footnotes.

Place cursor on graphics for citation and further information.

Sound clips are shown by the name of the song being in bold italic red text. Click the name and your installed MP3 player will start.

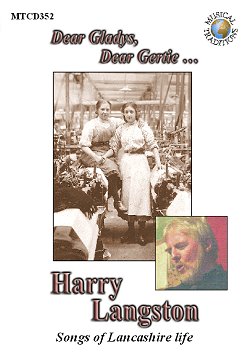

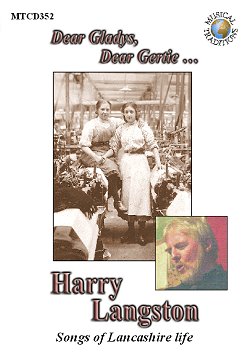

Harry Langston

Dear Gladys, Dear Gertie

Won't You Come Back to the Mill?

Songs of Lancashire life

Musical Traditions Records' fifth CD release of 2011: Harry Langston: Dear Gladys, Dear Gertie ... (MTCD352) is now available. See our Records page for details. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the record, or who might find the small print hard to read, I have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here.

Track List:

1 -

2 -

3 -

4 -

5 -

6 -

7 -

8 -

9 -

10 -

11 -

12 -

13 -

14 -

15 -

16 -

17 -

18 -

| Recall to Weavers

The Blackburn Poachers

Tackler Joe Proposes

Itís Nobbut Me

What Could Aw Say

Friends are Few when Fooak are Poor

A Lift Upon the Way

Coal Pit Lane

Accrington Pals

Pendle Sally

My Garden (Posey Joe)

Shuttle-Kissiní

Manchester Song (Rich Man - Poor Man)

A Song of Windmill Land

Scatter Your Crumbs

Love

The Coaler

My Piece is oí buí Woven Eawt (A Weaverís Prayer)

Duration:

|

1:25

5:30

3:08

2:44

6:55

3:59

3:46

2:21

6:41

5:47

4:05

2:36

2:24

4:47

1:44

6:03

4:37

4:1673:56

|

|

|

|

Foreword:

This CD is, I must freely admit, a bit of a surprise to find on the Musical Traditions Records label. A set of texts, few older than the 20th century, all with known authors, set to tunes composed during the last couple of decades by a known composer, who also sings them! But I promise you - if you like traditional English songs - you will absolutely love everything you hear on this CD. Wonderful, colourful, often passionate lyrics, coupled with some of the most glorious tunes you'll have heard for years. Added to that the fact that Harry Langston is a terrific singer who has fully overcome the 'curse' of a beautiful voice.

Harry wrote all the tunes to these songs himself, and also wrote the words to the song Accrington Pals. We have been fortunate to have had Harry as a regular at the Stroud singing sessions for many years, and I'm delighted to be able to share our good fortune wilth you.

Rod Stradling - Summer 2011

Introduction:

The recordings here are my musical interpretations of Lancashire dialect poems. I first came across the poetry when I was a teenager in Burnley in the 1960s, and, as they say, it seemed to leap off the page! A lot about it seemed familiar to me. The Burnley that I knew was typical of Lancashire cotton towns, and even in the early 1950s its appearance had changed little since the late 1900s, when much of the poetry was written. Some of the stories were like those I'd heard around me as I was growing up, and many poems used a form of speech that I knew well. My granddad - who was a spinner - spoke with a strong local accent. "Tha's got legs, tha mun use 'em!" - he would say, steadfastly refusing to use a bus even when he was in his 80s.

My father, Harry, met my mother, Hilda, at a dance at the Weaver's Club in Burnley, in the late1920s. They married and went to live in Fullage, where first my sister Mary was born, and then I arrived in 1948.

Many members of the family worked in the textile industry at some point in their lives, although the depression of the 1930s took some of my father's family to find work in Blackpool and the Midlands. When I was a young lad most were still living in Burnley.

Many members of the family worked in the textile industry at some point in their lives, although the depression of the 1930s took some of my father's family to find work in Blackpool and the Midlands. When I was a young lad most were still living in Burnley.

Like everyone else in Fullage, we lived in a stone terrace, 'cheek by jowl' with school, chapel and corner-shop. The factories and pubs were only a few streets away. The town and its streets were mostly still cobbled and lit by gas lamps, the buildings black, before the Clean Air Act of the 1960s. The mill chimney stacks and the home coal-fires, created a haze of smoke across town that could be especially bad in winter.

In 1955 we moved to the Barden area of Burnley. Although not far from Reedley Pit, everything there was lighter, greener and airier, and I was a great one for exploring. Attracted by the noise of the engines at Brittania Mill across the road, I sometimes peeked in at the mill yard, hoping to catch a glimpse of the great steam-engine in action. If I got to be seen I was soon chased out! All the old textile mills, one by one were being taken over for new purposes, and my father got a job at the engineering firm that started up on the premises of Britannia Mill.

At Barden there was a lot of popping in and out of each other's homes, as my Uncle Norman and Aunt Annie and family lived just around the corner. If my father's family got together, they often went out to enjoy themselves in a pub or club, sometimes singing medleys of popular songs from their youth. I was the late-comer to the family, so didn't get to hear much of it, but my mother and my Aunt Rose were enthusiastic about the good times. Not so long ago, Aunt Rose talked to me about the large family and the Sunday gatherings with singing around the fire. My father and his brother Bob - she said - often led the proceedings:

"Bob" she said (Bob was my uncle) "and Harry were cocky young fellas - they had a terrific sense of fun, the family would sit round the fire and the pair of them would sing. Bob would roar! But Harry had a sweet tone to his voice, everyone said so - "Isn't your Harry a treat", they used to say!"

Aunt Rose herself sang popular songs in the local clubs and pubs for a couple of years during the 1930s. I asked her if she knew - The Two Burnley Mashers - a Burnley version of a song popular in many Lancashire towns, (with the town name changed to suit). I began to sing it to her. Although she was in her late 80s, she immediately joined in the waltzy swing of it with real gusto and a strong, true harmony:

We are the two Burnley mashers -

That's because we go out on the mash -

We wear our tall hats

with no shirts to our backs

And it's seldom we have any cash.

We often bring out the new fashions

While others they stick to their old

And though we are just twenty seven

We're handsome stout-hearted and bold

And we'll sing tra-la-la

as we walk down the street,

For style and perfection

we ne'er can be beat.

All the ladies declare that we are a treat

We're the two Burnley mashers

from St James's street.

Harmony singing was very popular in the local chapels and churches. At chapel I could listen or join in the singing, and sometimes choirs came together for special events. The effect of hundreds of voices in harmony - Wow!

I loved music, and, lucky for me, my secondary school had a great music tradition. It had a silver band and a full orchestra. Soon I was playing a cheeky clarinet in both and a recorder in a school consort. I also joined the Boys Brigade bugle band belonging to Angle Street Chapel.

I loved music, and, lucky for me, my secondary school had a great music tradition. It had a silver band and a full orchestra. Soon I was playing a cheeky clarinet in both and a recorder in a school consort. I also joined the Boys Brigade bugle band belonging to Angle Street Chapel.

I admit that I was no natural bugle player and after my first few practices at home my parents suggested that I try something else. Never daunted, the next instrument I tried was the big drum, but I didn't tempt providence by practicing this at home! Soon the opportunity came along to be the band's drum-major. There's nothing like a marching tune to cheer you up. I fancied the white gloves and mace, and telling people what to do. It sounded good to me - an offer I didn't refuse. The parades at the annual Whit-walks were grand affairs, several bands and billowing church banners winding down St James Street. There was I at the front of the band, twirling and throwing up the mace. It was a bit nerve-wracking as any puff of wind could alter the fall of it.

We got hired out one day by a chapel in the village of Cliviger and marched along the main road, approaching some terraced houses. I knew if I was going to do something spectacular, it had to be next to the houses (not next to the fields and cows) so as we got nearer, I thought this is it. People started coming out of their houses. With great dexterity I tossed the mace high in the air- and missed it. It seemed to roll around in the street forever, got tangled up with the ropes of the snare drum and I had the indignity of untangling it as the band was still marching on - much to the hilarity of the onlookers.

About the age of 14, my friend Peter and I listened to some LPs of the great blues performer, Leadbelly, and other American folk music. Inspired, we formed a small band with a few friends, twanging out material like Joe Hill's Pie in the Sky and Carter Family classics. We played at local youth club and church events, where the line-up was banjo, guitar (me) and other motley instruments, harmonica, keyboard, drums. I've often wondered since about the effect we must have had on the local audience.

At 15, 'real life' took over. I became apprentice in a very traditional up-market high-class furnishing business, J H Hesketh and Sons of Burnley. Although I was only there for a few years, the experience made a huge impression on me. The workforce was made up of highly skilled men and women; cabinet makers, upholsterers, French polishers, soft furnishers and carpet fitters. Working with their hands, and a few pieces of cloth and wood, they created furniture and restored antiques that could (and did) grace some of the grandest homes in Lancashire.

At 15, 'real life' took over. I became apprentice in a very traditional up-market high-class furnishing business, J H Hesketh and Sons of Burnley. Although I was only there for a few years, the experience made a huge impression on me. The workforce was made up of highly skilled men and women; cabinet makers, upholsterers, French polishers, soft furnishers and carpet fitters. Working with their hands, and a few pieces of cloth and wood, they created furniture and restored antiques that could (and did) grace some of the grandest homes in Lancashire.

Many strands came together for me around that time. Youth Club got me into youth councils and local civic projects. Before long I was thinking about getting back into education. Camping trips to the Lakes led me to 'climbers' pubs and the wonderful discovery of British folk music. Inspired too, by Ewan Macoll's Radio Ballads, I bought a copy of The Singing Island and found a few other songs about Lancashire life. However, I learned the hard way that not everyone shared my enthusiasm for industrial ballads!

A friend and his county and western band were booked at (what I think was) the Tacklers Club on Briercliffe Road in Burnley. He asked me to do a spot to help out in their break. The evening came, the group finished their turn of American country music (dressed in appropriate cowboy outfits) and I mounted the tiny stage with my guitar, and stared through the dim haze to a sea of faces. Many of the audience were old enough to know well what my Lancashire songs were about. With complete confidence and the shining face of youth, I did my spot which included a few songs about the hardships of life in the cotton mills. My audience sat there silent and bemused. After the briefest of polite hand-claps they moved, as one man, to refill glasses at the bar and forget this kid telling them about hard work!

1968 was a time of some big changes for me, I'd returned to education and eventually got a place at York University. Leaving Burnley, I headed north across the Pennines on my scooter, guitar and everything else piled on the back.

Student life in the city, at the height of the late-60's folk-boom, was heady stuff. I heard the Watersons, the Young Tradition and the McPeake family, and the incredible harmonies made a huge impact on me. The local folk clubs in York were good too. Being from over the border, I felt obliged to stir things up with the occasional Lancashire song. My friends there would smile benignly and sing one of their own Yorkshire songs in reply. It was a wonderful time.

Work and study took me all over the country in the early 1970s. I lived for a time in Bath, then back up north to Middlesborough, where I spent a bitter winter on the edge of Hutton Rudby. It was so cold that on some mornings I had to warm the spark plugs of my old car in the oven to get it started. The early '70s were also a bleak time to be looking for work, but eventually I found a lecturing job in Bristol, and moved south again.

There were some great folk clubs in Bristol, well-established, with plenty of local talent, and an ever-changing population of singers. Some performers were from Scotland and the North, and many became good friends. People began to refer to me as 'Lancashire Harry' and I felt encouraged enough to slip in a few songs that contained some dialect.

I had been making up tunes for some of my collection of Lancashire dialect poems, since the late '60s - mostly just for my own entertainment, but occasionally I tried one out in public. I kept checking for bewildered faces, because I felt - as I still do - that there is not much point in singing a song if the audience are completely baffled by it. I want (most of) the words, and the sense and spirit of each song to be understood by all listeners, so I tend to choose poems with this in mind. There are words that may need to be explained - hence the Glossary at the end of the booklet.

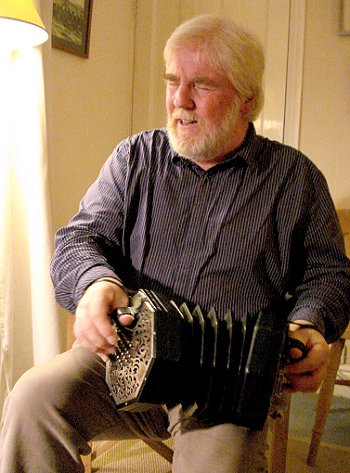

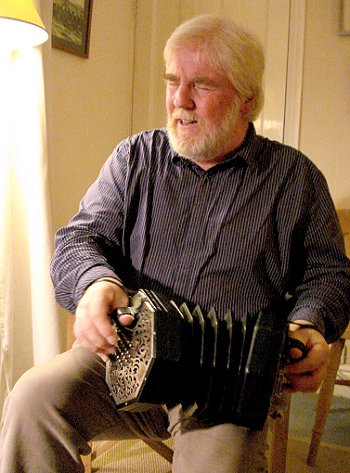

On the instrumental side, I played banjo, guitar, or concertina as accompaniment to some of the songs, others I sang on their own. In the late '70s there was a big wave of interest in early instruments and Early Music.  I'd never lost my love of playing the recorder, so I joined a consort where I sang early songs and played recorder and crumhorn. We performed everywhere, from streets to castles and medieval banquets - I've always had a streak of the showman, and I really enjoyed these. Another Bristol group got started where I sang '30s jazz numbers. At other times, I joined in with music-hall events. Looking back, I think the music experiences fed, rather than watered down my approach to traditional folk music, which has always been my central interest.

I'd never lost my love of playing the recorder, so I joined a consort where I sang early songs and played recorder and crumhorn. We performed everywhere, from streets to castles and medieval banquets - I've always had a streak of the showman, and I really enjoyed these. Another Bristol group got started where I sang '30s jazz numbers. At other times, I joined in with music-hall events. Looking back, I think the music experiences fed, rather than watered down my approach to traditional folk music, which has always been my central interest.

'Fairlands Ale' was a watershed event for many of us locally involved with traditional music in the mid '70s. It was an annual weekend hosted by Susie and Piers Blakeney-Edwards and their family, the 'Edwards family band' - held at their wonderful, rambling old house - 'Fairlands' in Cheddar, Somerset.  The orchard was given over to fire-lit dancing and games, and the barn, parlour and kitchen to song and music. Some of the country's most talented up-and-coming musicians and singers were invited along to share traditional music with the family and friends. Jim Small, a fine local singer and harmonica player from Cheddar, could sometimes be coaxed to join the 'sing' around Susie's kitchen table. Jim's quiet approach and commitment to his local material was a real inspiration, I felt he was 'the genuine article'. The Cheddar choral tradition that he had grown up with was strongly evident in his singing, and it had resonance with me.

The orchard was given over to fire-lit dancing and games, and the barn, parlour and kitchen to song and music. Some of the country's most talented up-and-coming musicians and singers were invited along to share traditional music with the family and friends. Jim Small, a fine local singer and harmonica player from Cheddar, could sometimes be coaxed to join the 'sing' around Susie's kitchen table. Jim's quiet approach and commitment to his local material was a real inspiration, I felt he was 'the genuine article'. The Cheddar choral tradition that he had grown up with was strongly evident in his singing, and it had resonance with me.

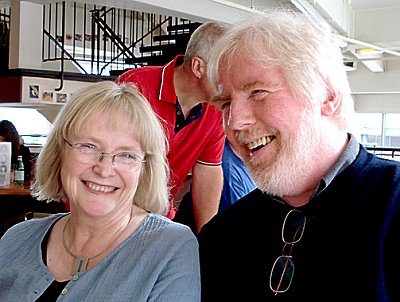

In the late '90s, my wife Chrissie and I heard about a pub called The Golden Fleece, in Stroud, Gloucestershire, where there were some 'very good singers'. In a small back room songs were shared (and still are!) amongst an appreciative group seated around a table. The emphasis at the Fleece gathering (now at another pub in Stroud) is on 'singing the story' without instrumental backing to the songs. This approach seems to work well with many of the Lancashire dialect songs, as it allows considerable freedom for presentation.

Chrissie and I, together with friends, have our own regular event in a small back-room at a pub in Hotwells, Bristol. Our get-together incorporates some instrumental breaks alongside the songs. Hotwells is also the practice-home of an extended group of good long-term friends named the Hotwells Howlers. The Howlers revive and perform west country tunes and traditional song material, sometimes combining it with folk theatre. We take it to wide audiences in and around Bristol and the west.

The Songs:

Recall to Weavers

The Blackburn Poachers

Tackler Joe Proposes

It's Nobbut Me

What Could Aw Say

Friends are Few when Fooak are Poor

A Lift Upon the Way

Coal Pit Lane

Accrington Pals

Pendle Sally

My Garden (Posey Joe)

Shuttle-Kissin'

Manchester Song (Rich Man - Poor Man)

A Song of Windmill Land

Scatter Your Crumbs

Love

The Coaler

My Piece is o' bu' Woven Eawt (A Weaver's Prayer)

Some of the Lancashire poems were written in dialect form, using the everyday speech of their time. To imitate local pronunciation the poets often used a phonetic spelling. Lancashire dialect has always varied throughout the county, sometimes posing a problem for the performer. I find it best to use the Burnley accent, and sometimes the dialect, with which I am most familiar. There will be a few variations in my phrasing and pronunciation (singer's license!) but I have mostly noted where I have strayed from the original published texts, which are given below.

Many of the poems here will be well known in the north of England, others less so. Some of them were created as songs, and some have already been set to some good melodies, but all the tunes used here are my own, drawn from my musical experiences.

Harry Langston - Summer 2011

1 - Recall To Weavers

In the early 1970s I met an ex-cotton mill worker, May Jewitt. We were talking at her home in Burnley, when she opened a sideboard drawer and pulled out an old newspaper cutting containing this piece of satirical verse. The cheery, enticing tone was very much at odds with the recollections of the mills that I heard from my mother, and from May herself.

Sir Stafford Cripps was member of the 1945 post-war Government led by Clement Atlee. He strove hard for a recovery of Britain's fortunes, and his focus on the cotton industry led to a string of unpopular austerity measures. Two world wars, poor investment, lack of modernisation and the privations of the 1930s depression left a lot of workers with a deep desire to look for opportunities and work elsewhere. Cripps had a stern manner and this piece of satire followed his clarion call back to the cotton industry. This is in tribute to May, who kindly passed it on to me. A jaunty tune seemed appropriate.

Recall To Weavers

Dear Gracie, dear Gladys, dear Gertie

Dear Gracie, dear Gladys, dear Gertie

O won't you come back to the mill

I'll keep you all busy

Dear Lucy, dear Lizzie,

If only you'll say that you will.

Come back to your spinning and weaving

The labour is easy and clean,

With short working hours

And concerts and showers

And meals in a cosy canteen.

Come back, all you Lancashire lasses

And share in the new cotton boom

The jobs you've foresaken

Have never been taken

Come back to your old love - the loom.

O join in our new working party,

And business will never be slack,

Dear Daisy, dear Susie

Please don't be so choosy

Or Cripps will be hot on my track.

Dear Annie, dear Fanny, dear Jenny

Dear workers, I wait for you still

The past is forgotten

Your future's in cotton

Come back to your old love, the mill.

2 - The Blackburn Poachers

Similar versions of this song can be found up and down the country. I found this one browsing though some newspaper cuttings dated 1870 - 1876 in Burnley Library. I don't know if it was based on a real local event, but like to think it is. I thought that I would put a lively tune to it, to counterbalance the moralistic and instructive tone of the verses.

The Blackburn Poachers

Come all you wild and thoughtless youths,

And list awhile to me,

A dismal tale I will relate

That should a warning be,

It's of four men from Blackburn town,

On killing game intent

Upon the lands of Billington

One night a poaching went.

Chorus:

Now all beware you Blackburn Lads,

Lest you're drawn into a snare

To learn the trade o' poaching

On the clear night air

Now as they beat about the grounds,

No keepers then were nigh,

Loud echoed through the silent wood,

The startled pheasants' cry;

And to each other they did shout,

My lads look out for game,

Which sounding on the still night air,

Four keepers quickly came.

Now all the men were armed with guns,

With powder, and with shot,

And the keepers said, "Lay down your arms,"

But the poachers they would not;

Some angry words arose, and then

Began the bloody fray,

Which ended in the keeper's death

Upon that fatal day.

The keepers then a poacher seized,

Who cried, must I be bound,

Then a poacher shot a keeper,

Who fell upon the ground,

And he is numbered with the dead,

We shall not see him more,

But o'er his sad untimely fate

His kindred now deplore.

In Lancaster the poacher lies

His trial now to take,

For spilling of a brother's blood

His life is now at stake

Oh! What must be the torturing pangs

That wring the guilty breast,

As lingers on the dreary night,

His soul can have no rest.

Whene'er we hear of sudden deaths,

Sad thoughts our bosoms fill

But when by man, man's blood is shed,

It is more awful still,

The murder'd keeper is no more,

And now he's run his race,

He's gone beyond the grave to meet

His Maker face to face.

Ye will young men from this sad tale

A solemn lesson learn,

If e'er enticed by wicked men,

From their allurements turn,

The ways of virtue are the best,

They bring us peace at last,

Contented is the poor man

When all his toil is past.

3 - Tackler Joe Proposes

Mary Thomason 1863 -1937

Mary Thomason lived all her life in Westleigh. Her long career as a teacher in Leigh began at the early age of 13 and she went on to become actively engaged in the wider educational life of the town. Though her skill as a writer and her shrewd observations of local life she became a well-regarded member of the Leigh Literary Society. She was a passionate advocate of the use of dialect. Of standard English she wrote: 'to learn it well I always sought / but oft I thought it all too weak / to utter thoughts I wished to speak'. Tackler Joe Proposes was one of the first of her poems to catch my eye, and it's typical of her down-to-earth way of dealing with a ticklish subject.

Tackler Joe Proposes

Tackler Joe to Mary said,

"Wilt take a walk wi me

And I will try to show thee, lass,

How dearly I love thee?"

"At talking I am not so glib,

No words my love can tell,

But I will take thee in my arms

And that will do as well.

And if my ways thy fancy please,

I'll tell thee what to do,

Just put thi arms about mi neck,

And give a little squeeze."

"All right" said Mary, "come along

I've often see thee smile.

I knew theay'd soon be axing me

And I've loved thee quite awhile"

"At talking I am not so glib,

No words my love can tell,

But I will put my arms round thee

And that will do as well.

And if thy ways mi fancy please,

I'll draw thee nearer to me, lad,

And give a little squeeze

Joe and Mary then set off,

A quiet spot they found,

Beneath a widely spreading tree,

Upon a little mound.

They neither were at talkin' glib,

No words their love could tell,

They cuddled in each other's arms,

And that was quite as well.

Joe's ways did Mary's fancy please,

And she knew what to do,

She put her arms about his neck,

And gave a little squeeze.

4 - It's Nobbut Me

John Holt 1842 -1919

John Holt lived all his life in Radcliffe, Lancashire. Like many of the dialect poets, he was a mill-worker who wrote during his few leisure hours. He was in great demand for his recitations, and it's easy to understand why. This is a witty poem, full of tease, and I really enjoy singing it.

It's Nobbut Me

One winter's neet aw'st ne'er forget,

Eaur lads coom in fro't dell'

Un bein' tired went soon to bed;

Un, as aw sit misel',

Aw yerd a jink on t'window pane,

Un quietly went to see;

But when aw axt "Who's jinkin' theer?"

Say's chap, "Its nobbut me."

"Who's 'me'?" says I, "What dusta want?

Eawr foaks are o' I' bed."

"Aw dunnot want yo'r folk ut o -

It's thee aw want," he said.

"What dusta want wi me?" says I,

"Un who the deauce con't be?

Just tell me who it is," says I.

Says he, "It's nobbut me."

"Aw want a sweetheart, un aw thowt

That thea met want one too,

So, as aw'm goin' past, aw co'd

To see if aw should do.

Well, would ta like mi, dusta think? -

Aw'm sure aw should like thee."

"Eh, aw durn't know who 'tis," says I.

Says he, "Its nobbut me."

We chatted on tidy while,

'Til aw geet on t' reet scent;

Un then aw strode across t'house floor

Un out o'th' dur aw went.

Aw crept un catched him bi'th coat laps -

'Twur dark, he could not see;

So he twisted round, and said, "Who's that?"

Says I, "Its nobbut me!"

Un mony a time he come agen,

Un mony a time aw went,

Un said, "Who's that what's jinkin' theer?"

Weel knowin' what it meant.

Un then aw yerd t'same answer come

Fro' t' back o'th apple tree;

He said, "Aw think thea knows who 'tis -

Thea knows it's nobbut me."

It's twenty yer or moor sin' then,

Un ups an' downs wi'n hed,

While six fine childre's blest us both,

Sin' Jim an' me wur wed;

Un mony a time aw've know him creep

When one's bin on mi knee,

Un made mi start, un then would laugh;

"Ha, ha-it's nobbut me!"

5 - What Could Aw Say?

William Barron 1865 -1927

This comes from William Barron's collection of poems entitled Tales from the Loom. William - a mill-worker from the age of 12 - followed in his older brother Jack's footsteps as a dialect poet, using the pen-name 'Bill 'o Jack's' (his brother was 'Jack 'o Ann's). He was a regular contributor of dialect sketches for the Blackburn Standard by the 1880s, and several volumes of his humorous and homely verse were published in his lifetime. Homely is the word for this poem - my wife loves the images of the gentle courtship that happens around a bucket. I like the poem's delicate sensitivity, so I set it to a waltz tune, which I have now called Chrissie's Waltz.

What Could Aw Say?

Aw'd just stopped to rest me,

A bit past th' owd farm;

For t' basket wur heavy,

An t' weather wur warm

Aw wur listening' to t' woodlark

I' t' thicket beyond;

While t' sunbeams danced gaily

On t' surface o' t' pond.

But o of a sudden

A footstep drew near;

An' when aw look reand me

Blithe Roger wur theer,

He smiled-eh, so kindly,

An' bid me "Good day!"

Then axed to goo wi' me-

An' what could aw say?

When aw stooped down for t'basket -

"Howd on theer," said he;

"Aw'll carry it for tha-

Tha'rt tired, aw con see."

Sooa he took it up leetly,

An' gaily he talked;

But his language grew sweeter

As farther we walked.

When t' market wur ended,

We walked back once mooar,

An' he clung to me closely

'Til reychin' th' heawse door.

Then he axed me to meet him

On some other day;

An' aw raised no objection-

For what could aw say?

We met two days after-

Aw'd gone deawn to t' well;

But soon aw discovered

Aw weren't bi misel'.

Oh! He mun ha' bin watchin',

For me he espied;

An' afore aw'd filled t' buckets

He stood by mi side.

"Eh, do let me drink, lass!"

He said wi a grin;

But he none wanterd t' wayter -

'Twur me at he'd sin.

An' while aw hoisted t' well rope,

He chattered quite gay;

Then he bent o'er and kissed me-

An' what could a say?

That wur but th' beginnin'

O' what had to be;

For many a ramble

Had Roger an' me.

June changed to December-

December to May;

An' eawr luv, wi acquaintance

Grew stronger each day.

But one neet, when ramblin

'Throo' t' meadows so green;

He pressed mi hand softly,

An' glanced I' mi een

An' he talked, an' he pleaded,

In such a nice way;

Then he axed me to wed him-

An' what could aw say?

Now aw luv to hear' t' woodlark

I' t' thicket beyond

An' remember those sunbeams

On t' surface o' t' pond.

6 - Friends are Few when Fooak are Poor

William Billington 1825 - 1884

A magnificent poem by William Billington 'The Blackburn Poet'. At the age of 14 he was a power-loom weaver. Through self-education he became a teacher, and later a publican. He was a highly regarded and pivotal figure in Blackburn literary life and his public house was a well-known meeting place for local writers and poets. He was involved with the Trades-union movement, and a man of strong convictions, as this poem clearly tells. It carries a sad and bitter message that if one loses money and if status declines, then business acquaintances, friends, and in this case, even family - may also be lost. Billington wrote this around in 1861, and it's likely that it reflected the devastating consequences of the cotton famine that lasted from 1861-1865.

Friends are Few when Fooak are Poor

When aw hed wark, an' brass to spend,

Aw never wanted for a friend;

Fooak coom a campin' every neet,

An moved when meetin' me I'th street;

Mi company were cooarted then

Bi business chaps an' gentlemen -

Aw ceawnted comrades then bi't scoor,

Bur neaw aw've noan, becose aw'm poor.

Aw'd invitations every day,

To dine, or sup, or teck my tay,

Or caw an' hev a friendly chat

Wi Mr. This and Mrs. That;

An Squire Consequence, to boot,

Ud ax me o'er to fish - or shoot

Wi dog an' gun o'er fell an' moor -

But that's knockt off, becose aw'm poor.

Then Scotchmen bothered me wi' goods,

An' tongues as smooth as soft-sooap suds,

For partronage; an' strove to ged it

Wi' yeards o' cloth, an' years o' credit!

Bud neaw they'n torned ther tune, bi th' mass;

Some's hawkin tay- for reddy brass!

Some kornd si th' number o' mi door.

They'n groon so blind, sin' aw grew poor.

An' wod mecks matters look moor feaw,

Mi kinsfooak doesn't know mi neaw;

Puffed up wi' pride to sich a pitch,

They'n no relations- bud wot's rich!

An' even my own brother Jim'

He ses aw'n nowt akin to him -

"Bi gum!" thowt aw, "bud that's a througher,

A mon's a boggart when he's poor."

Aw know there's t' Warkheawse when o's done,

Bud whoa likes gooin' to th' Union?

Aw'd liefer lay mo deawn an' dee

Nor live on public charity!

On parish pay, or teawn's relief

One's looked on next door to a thief;

An wonst inside o'th Warkheawse door,

They'll keep yo alive, bud nod mich moor!

Sooa th' world wags on, fro day to day,

An' still id ses, or seems to say,

"This poverty's a deadly sin

Wod baniches booath friends an' kin,

An' stinks in every noble nooas."

Sooa yo, who've nother meyt nor clooas,

Mun live o'th air, an lie o'th floor,

An serve yo reet - becose yo're poor.

7 - A Lift Upon the Way

Edwin Waugh 1817 -1890

This splendid poem comes from the mid 1850s, a period when Edwin Waugh was enjoying considerable acclaim. He began his working life as a printer's apprentice, and worked around the country as a printer. He returned to his home town of Rochdale, finally leaving the trade in 1847 to take up secretarial work.

He achieved fame with the poem Come whoam to thi childe an' me in 1856. Waugh was one of the founders of the Manchester Literary Club and became known as 'The Lancashire Burns'.

I found the poem A Lift on the Way in a cutting from an old newspaper in Burnley reference Library during the 1960s, and immediately liked the words and the up-beat spirit of it. Some time later, after I had set my own tune to it (and slightly adapted the title words) - I found a copy of A Set of Twelve Songs by Edwin Waugh which included the poem set to music by Robert Jackson. However, people seem to like the tune which I've used since the '70s - and I have stuck to it.

A Lift Upon the Way

Come what's th'use o' fratchin', lads,

This life's noan so lung,

So if yo'n gather reawnd,

Aw'll try my hond at sung;

It may shew a guid-in' glimmer

To some wand'rer a stray.

Or, hap-ly, gi' some poor owd soul

A lift upon the way:

Chorus:

A lift upon the way;

A lift upon the way;

Repeat the last lines of verse.

Life's road's s' full o' ruts its very

Slutchy and its dree

And mony a weary traveler

Lays him down there t' dee

Then flounderin about I'th gutter

He looks round him wi' dismay

To see if ought I'th wold can gie him

A lift upon the way

There's some folk at' mun trudge it,

An' there's some folk at' mun ride,

But, never mortal mon con tell

What chance may betide;

To-day, he may be blossomin',

Like roses I' May;

To-morn, he may be beggin' for

A lift on the way:

Good-will, it's a jewel, where there's

Little else to spare;

An' a mon may help another

Though his pouch may be bare;

A gen'rous heart, like sunshine,

Brings good cheer in its ray;

An' a friendly word can sometimes give

A lift upon the way

Like posies that are parchin'

In the midsummer sun'

There's mony a poor heart faints afore

The journey be run;

Let's lay the dust wi' kindness,

'Til the close of the day,

An' gi' these droopin' travelers

A lift on the way.

Oh, soft be his pillow, when

He sinks deawn to his rest,

That can keep the lamp o' charity

Alive in his breast;

May pleasant feelin's haunt him

As he's dozin' away,

An' angels give him up aboon,

A lift on the way

Jog on, my noble comrades, then,

An'so mote it be -

That hond in hond we travel 'til

The day that we dee;

An' neaw, to end my ditty, lads,

Let's heartily pray

That heaven may give us, ev'ry one,

A lift on the way.

8 - Coal Pit Lane

A wonderfully crafted poem by Mary Thomason. A catastrophic event at the colliery turns hope into despair in an instant. The precarious nature of mining life is seen from the woman's point of view; her story conveyed in the rhythm of a treadle sewing machine - and the reference to the 'half-made dress' is a truly original inspiration. It took me a long time to work out a tune that seemed to suit the sense of it.

Coal Pit Lane

Up the Lane and down the Lane

When passing to and fro.

From home to work and back again

I watched the colliers go.

I watched them through the window

That gave me light to sew.

Whirr, whirr! Whirr, whirr! Went my machine

As I did sit and sew,

And I always saw one collier lad

As he passed to and fro.

Up the Lane and down the Lane

When stars shone in the sky,

Together linked with arms entwined

Went collier lad and I.

And as he told his tale of love

Too quick the time did fly.

Forgot the whirr of my machine

Forgot the half made dress,

Forgotten all but collier lad

While he did my lips press.

Up the Lane and down the Lane

No longer colliers go;

The mine is wrecked, the colliers dead

Are lying down below;

And stricken wives and mothers

Are passing to and fro.

Stopped is the whirr of my machine,

My head is bowed with woe,

And ne'er again my collier lad

Will by my window go.

9 - Accrington Pals

It wasn't until some years after first learning about the Accrington Pal's Brigade, that I read William Turner's books, Pals and The Accrington Pals. Looking at the photographs, I was appalled to think not only were most of these lives lost, but extended families and entire communities were devastated by the policy of the Pals Battalions.

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 the British Government appointed Lord Kitchener as Secretary of State for War. Kitchener felt strongly that the war was likely to last for years and that there would be a need to substantially increase the size of the army. The Government sought to raise a volunteer army of one million men.

It was thought by some in the military that men might be more willing to join-up if in the army they were with friends, neighbours and workmates that they knew from their town or locality. One of the first to try and put this recruiting idea in to practice in Liverpool from August 1914 was Lord Derby. He was said to have coined the phrase 'battalion of pals'. Kitchener adopted the idea and encouraged Pals Battalions to form all over the country.

The Accrington Pals Battalion was formed following an offer to raise one by the Mayor of Accrington, John Harwood, JP. The offer was accepted on 7th September, 1914, and recruiting offices were opened in Accrington, Burnley, Blackburn, Chorley and some other small towns around Accrington. In the wave of national fervor, thirty-six officers and 1,076 men enlisted for the Accrington Pals within ten days, during the autumn of 1916.

When writing the song, I used the name Jimmy Jowett; a fictional character swept up in these events.

Accrington Pals

Little Jimmy Jowett

Little Jimmy Jowett

Left his own fireside,

He stowed his clogs donned soldier's togs

And filled his street with pride,

With many of his pals

he answered to the call,

For Kitchener and Country

He went out and gave his all.

Chorus:

And the band played on as the

Pals they marched on by,

Be proud little Accrington

don't weep for them or cry,

For those friends and brothers

Did that day make a stand,

To fight for duty, kith and kin

And our beloved land.

Men from other mill towns

Answered to the call,

Others came from villages

And market town and Hall,

Happy bands of comrades

Together in one mind,

To join the Pals of Accrington

And with them honour find.

In the spring of 1916

From Egypt's burning sand,

The Pals were drawn towards a storm

On France's stricken land,

Towards a living hell

Of mud, bullet and bomb,

Sucked in towards a carnage

Called the battle of the Somme.

Near a place called Serre

On the first day of July,

700 Pals went o'er the top

And looked death in the eye,

By the falling of the sun

The terrible price was then,

600 dead and injured

Gallant Lancashire men.

Yesterday a baker,

A collier, a dad,

An engineer, a tackler

Or even just a lad,

Striving to be happy

As many one before,

Now youth to ashes

In the Great World War.

One less at the table,

One less at the dance,

One voice less in't chapel choir,

It stopped and died i' France,

One more widow in the street

Who kept the fires alight,

And one more child up in it's bed

Who cries for dad at night.

Tell a tale of peaceful times

And tell of what it cost,

Tell a tale of sacrifice

Of men and youth now lost,

Tell a tale of families

Who fought at home their way,

And never let it be forgot -

Just tell it every day.

10 - Pendle Sally

Robert West Whalley 1848 -1904

Whalley became a weaver in the Blackburn weaving sheds at the age of 10. He was already well-known for his recitations, and by his late teens his character sketches and poems drew him to the attention of Blackburn poet William Billington, who became Whalley's mentor and friend. Pendle Sally (originally entitled Sabden Dick) was written by Whalley for a Padiham singer, Robert Moorhouse, who apparently won several competitions singing it.

I found the words of Pendle Sally in Blackburn Reference Library in the 1960s, in an old book of dialect poetry. I think the words have such authenticity and passion that they may be interpretted in different ways. Although it seems likely that it was intended to be a comic song, I saw the poem as a genuine love story, a real rhapsody. I set it to music in the late '60s, and I still love singing it.

Pendle Sally

At Boggart Nook, at foot o' th' hill,

Up lonely Sabden valley,

Theer lives a bonny, buxom wench -

They ca hur "Pendle Sally."

Hoo is a shepherd's lass,

An' scanty is hur fortchin';

Fost time aw see'd hur mindin' sheep

Hoo seet mi heart a-wortchin'.

Chorus:

Hoo is to' good for sich as me

To lay their dirty hands on,

Aw var' near worship t' greawnd as

Little Pendle Sally stands on:

If every field an' farm were mine

Theer is i' Sabden valley,

Oh, if Pendle Hill wer med o' gowd,

Aw'd give id all for Sally.

My heart strings nearly broke i' two;

T' seet on her fairly crackt 'em.

Hoo's cheeks as red as if hur mam

Hed nabbut lately smackt 'em

Theer isn't sich another lass

Fro' Wiswell Top to Kendal;

Hur e'en eawtshines thad big bonfire,

At Jubilee on Pendle.

Neet after neet aw wakken lie -

Aw connod sleep for skeomin';

An' when bi day aw werk i' t' delf,

Of hur aw'm sooart a' dreeomin'.

At dinner-time aw chew an' chew,

Bud nod a bit can swallow;

Mi cheeks, once red as carrots scraped,

Are neaw as white as tallow.

Mi feyther says aw'm geddin' daft;

Sometimes he'll fairly crack eawt,

An' sweear if aw dornd wakken up

He'll come an' jerk mi neck eawt.

To-day aw leet mi barrow fo -

He sheawts to t' ganger, "Harry!

Just ta'e thad gaumless foo' a' mine

An' punch him eawt o' t' quarry."

Sich work as this 'll never do;

Aw'll oather end or mend id,

As soon as ever t' week-end comes,

Mi pocket brass aw'll spend id

I' summat nice for hur; an' then,

Fast as mi legs 'll ta'e me,

Aw'll hook id off to wheer hoo lives,

An' ax hur if hoo'll ha'e me.

If hoo says "Nowe!" aw'll goo an' list,

An' end mi days i' feightin';

If hoo says "Aye!" aw'll hurry hooam,

An' buckle to mi eytin'.

We'll nod be long afoor we're wed,

An' ringers twitchin' t' bell strings;

Then we'll goo o'er bi Pendle Nick,

An' hev a spree at Well Springs.

11 - My Garden (Posey Joe)

Joseph Cronshaw 1851 -1921

'The Ancotes Bard', Joseph Cronshaw, strikes me as an enterprising and sparky character. As a lad he hawked salt from a donkey and cart, eventually becoming a grease refiner and salt merchant on a large scale. As well as a sideline of keeping a stud of donkeys on Blackpool beach, he performed energetic 'turns' on stage. These were developed from studies of characters he encountered on the Salt Wharf at Anchotes.

When we moved to Barden, I remember the impact that suddenly having a garden made on us all - my father liked his lupins, dahlias and marigolds. Cronshaw perfectly encapsulates the joy of a treasured 'bit o' greawnd' in this delightful poem. I cannot lay any claim whatsoever to be a gardener (my wife is the expert in our house) but I do recognise the passion in others - and I do seem to get a lot of requests to sing it.

My Garden (Posey Joe)

Aw've a bonny little garden

Reet full o' pratty flowers

An' when it's leet till late at neet

Aw spend some happy hours;

Wi' reet good will aw tak' mi spade

An' delve an hour or so,

An' then aw sit, an' smook a bit

An' watch my posies grow.

There's scores o' folk would give a lot

To live a life like mine.

Aw'm reet content for blessings sent

Bi' th' weather weet or fine.

Old Sol may hide his face awhile,

But then, yo' see, I know

It tak's some rain as weel as sun

To make my posies grow.

There's lots o'bees an' butterflies

Come sippin' fro' each bell;

There's music sweet, morn, noon an' neet,

Comes fro' yon little dell.

There's throstles pipin' loud an' clear,

While finches, sweet an' low,

Join in a chorus as I sit

An' watch my posies grow.

Aw've polyants an' gree' house plants,

Grand roses, too, as well,

Tall hollyhocks, an' phlox, an' stocks,

Far more nor aw con tell.

Neaw, should yo' ever come this road,

Just ax for Posey Joe;

Aw'll tak' yo' reawnd my bit o' greawnd,

To see my posies grow.

12 - Shuttle-Kissin'

Sam Fitton 1868-1923

Sam Fitton started work as 'a half-timer' - a piecer in the Rochdale cotton-mills at the age of 11. Already a good mimic, his character drawings began to appear on the factory walls. Remarkably, his tolerant employer sent him to Oldham Art School for some training, and Sam became celebrated for his cartoons as well as his mimicry. He won a number of local competitions for his recitations, and Shuttle-Kissin may be one of these - a dialogue between the sexes played out in the work context. It gave me a laugh when I first read it, and it reminded me of the antics of some staff at my first workplace when I was an apprentice upholsterer.

The thread that played out from a shuttle as cloth was weaved had to be passed through an eye hole in the side of the shuttle before weaving could start. A weaver had to put the shuttle against the mouth and suck the thread though the eye hole. This was referred to as 'kissing the shuttle'. It was an unhealthy, even dangerous practice, as cotton threads and dust were sucked into the weaver's lungs, and oil on the shuttle could lead to cancer of the mouth. Later on in the 20th century, shuttle technology (the 'patent thingammy') removed the need for weavers to 'kiss the shuttle'.

Shuttle-Kissin'

Matilda Curly Toppin' wer'

A weighver, an' a lass

Who did her share o' laughin',

An' earned her share o'brass

Hoo kissed her share o'shuttles, too,

But if they'd nobbut let her,

Hoo'd rather pass her time away

I' kissin' summat better.

Matilda had a tackler

Who'd getten very free

Wi' bonny Curly Toppin',

For he kept her in his e'e;

But th' way this felly pestered her

Amounted to a craze,

An' hoo wer' getting' wary of his

Spooney little ways.

Hoo couldn't stir a peg but he wer'

Awlus at er heels.

He followed her I' th' factory,

Or goin' to her meals;

So once as hoo wer' comin' wi'

A shuttle fro' his bench,

He blurted eawt, "Matilda,

Tha'rt a gradely pratty wench;

"I dunno' want to see thi

Kissin' shuttles o' thi life,

So if I wer' to ax thi,

Wouldta come an' be mi wife?

If tha'll gi' me thi kisses -

For I think tha's mony left -

I'll mak a patent thingammy

For suckin' up thi weft."

At that Matilda cocked her e'e',

An' shook her curly yed,

Then givin' him a little smile

Hoo wagged her yed an' said;

"I'm very much obliged for o'

Thi promises, shuzhaew,

An' yet I conno' marry thi,

For tha'rt so very feaw.

I'm sick o' bein' single,

An' I'm sick o' suckin' weft,

Mi teeth are getting' rotten,

An' I haven't mony left,

I thank thi for thi offer,

Which I very much decline,

For I'd rather kiss a shuttle

Than a face like thine!"

13 - Manchester Song (Rich Man - Poor Man)

Elizabeth Gaskell 1810-1865

Elizabeth Gaskell was born in Chelsea London, but as a girl, moved to Knutsford, Cheshire, to live with her aunt. In the 1830s she met and married a minister, William Gaskell, and they went to live in Manchester. She was deeply shocked by the contrast between sleepy Knutsford and the squalid conditions of working class life in industrialised Manchester, the city that formed the background to her first novel Mary Barton, published in 1848.

I have listened to the accounts of those who suffered the consequences of unemployment in the 1920s and '30s and how they struggled to avoid the hated Means Test for National Assistance, set up under the brittle authority of the time.

In Mary Barton, Elizabeth Gaskell describes the terrible plight of unemployed families in 19th century Manchester, who found themselves with no financial support whatsoever. 'Manchester Song' heads one of the chapters in the novel, and the words have a bite that I found difficult to ignore.

In setting this to a tune, Chrissie and I made a few adjustments to the final words.

Manchester Song (Rich Man - Poor Man)

How little can the rich man know

Of what the poor man feels,

When want like some dark demon foe

Nearer and nearer steals!

He never tramp'd the weary round,

A stroke of work to gain,

And sicken'd at the dreaded sound

Which tells he seeks in vain.

Foot-sore, heart-sore, he never came,

Back through the winter's wind.

To a dark, dank cellar, there no flame,

No light, no food, to find.

He never saw his family lie

The flagstones for their bed,

And he never heard his childre' cry

For warmth and want of bread.

(The original reads as follows:)

He never saw his darlings lie

Shivering, the flags for their bed,

And he never heard that maddening cry

"Daddy, a bit of bread!."

14 - A Song of Windmill Land

Allen Clarke (Teddy Ashton) 1863 - 1935

Clarke had a remarkable career. He worked his way out of the cotton mills by becoming a pupil-teacher, then a journalist. In 1891 he established Lancashire's first Labour newspaper, Labour Light. In 1896, using the pen-name Teddy Ashton, he brought out Teddy Ashton's Journal - read by thousands of mill-workers. He actively promoted the work of Lancashire writers and became the chief founder of the Lancashire Author's Association, in correspondence with leading literary figures who included Thomas Hardy and George Bernard Shaw.

He was the author of many novels, and his writing contributed to the campaign against child labour in the cotton mills. The Effects of the Factory System was translated into Russian by Leo Tolstoy. Windmill Land was written following Clarke's later rambles through Northern Lancashire in 1916. The reference to the loss of friends at that time, and 'such Eden as yet on earth remains' gives a post-WW1 poignance to the poem.

For short periods when I was young, I lived in Blackpool with my Aunt Alice and Uncle Albert. The resort always was an annual escape to the seaside for some clean air, a place for working families to let their hair down and have a good time. My family had its fair share of day trips and holidays to Blackpool and the Fylde coast area. The windmill was on the edge of Blackpool, and the first thrilling glimpse of it as we got near to the seaside was in my mind when I set this to music.

A Song of Windmill Land

O' the Fylde's a bonny country,

Of flowery lane and lea,

With mountains on the morning side,

And on the west the sea;

And a shining river winding through

The Windmill Land between -

Farms, orchards, cornfields, villages,

And woodland sweet and green.

O, the Fylde's as bonny country

As one can linger through,

With its glory of wild roses,

And its soothing skies of blue;

For when the winter's waning,

And the birds begin to sing,

'Mid the beauty of the blossom - O,

'Tis very heaven in Spring!

O' the Fylde's a bonny country,

When the gorse is all in gold,

And the plum-trees in their virgin white

Are bridal to behold,

When the amorous flush of apple-bloom,

Like a maid in shy desire,

Makes a picture and a promise

That the eye and heart admire.

O, the Fylde's a bonny country

With its glamour and its gleam,

With the music and the memories

Of true love and its dream -

Of the lass who rambled with me

In the romance of the lanes,

Where lovers find such Eden

As there yet on earth remains.

O, the Fylde's the bonniest country

In all the world to me,

Because of some who wandered there

Whom now no more I see,

But whom I hope to meet again

All mourning reconciled

In a land that's even fairer

Than the paradise of Fylde.

15 - Scatter Your Crumbs

Alfred Crowquill 1804 -1872

Alfred Crowquill is the only writer on the list who was not from Lancashire - he was a Londoner. A popular writer and illustrator of children's books (under the name Alfred Forrester or Forrestier) he also produced artwork for Punch magazine.

I have sung his poem for so many years as a Christmas song, alongside my Lancashire material, that it has 'settled in' and feels as though it belongs with the Northern repertoire.

Early music had an influence in the making of this tune - good for a sense of winter chill.

Scatter Your Crumbs

Amidst the freezing sleet and snow

The timid robin comes:

In pity drive him not away,

But scatter out your crumbs.

And leave your door upon the latch

For whosoever comes;

The poorer they; more welcome give,

And scatter out your crumbs.

All have to spare, none are too poor,

When want with winter comes;

The loaf is never all your own,

Then scatter out your crumbs.

Soon winter falls upon your life,

The day of reckoning comes:

Against your sins, by high decree,

Are weighed those scattered crumbs.

16 - Love

Thomas Brierley 1828 -1909

Brierley was a hand-loom weaver in Middleton, near Oldham. Despite the customary long working hours, he studied to gain mathematical skills and became auditor at several Middleton mills. Brierley is described as a retiring yet interesting character, who was openly proud of his dialect. He ran an evening school where he taught the 3 Rs to local children.

I smiled when I first read this poem about the persistent lover - 'popping his head though a gap in the hedge' - a waltz tune soon came to mind. To make a chorus, I took four lines from the original fourth verse, and wrote some more to fill the gap.

Love

Fust time 'at he talked abeawt love

Awst never forget it, aw think,

For tho' awr as flush as a rose,

Aw trembled as if aw should sink;

Aw kept mi two een upo' th' greawnd,

While softly he chanted love's tune,

But when aw fun th' use o' mi tongue,

Aw said it wur rayther too soon.

Chorus:

Thur' blue-bells an' daisies i' th' wood,

Thur' blossoms on every bush,

Th' hawthorns wur cream-like an' rich,

An' sweet were the notes of the thrush.

Next time 'at he started again,

Awr roamin' for berries i' th' dell,

He popped through a gap, an' he said,

"Art havin' a jaunt by thisell'."

Then he singled mi fingers i' his,

An' tried to look into mi een,

But aw begged he would not be so bowd,

For awr nobbut just turned seventeen.

Tho' aw liked him as weel as mi life,

When he axt me again, aw looked shy;

Aw felt 'at aw couldn't say "ay,"

An' it very nee made me to cry.

He urged me to wed him at once,

True love, he said, isn't a crime;

At last aw plucked up an' said, "husht!

An' aw'll gie thee an onsur next time."

That time it came on very soon

I'll remember it all of m' days

As we stood by the gate to the dell

In the glow of the twilight's last rays

When he pressed mi two lips to his own,

An' said, "con ta love me for good,"

Wi' cheeks like a fine rosy morn,

Aw whispered, aw thowt 'at aw could.

It's monny a lung year sin' that day,

An' neaw we'n some young un's to keep,

We'n two 'at are goin' t' skoo,

An' one 'at's i' th' kayther asleep;

Eawr life passes on like a dream,

Mi husband an' me never fret,

We con buss one another, an' say

"We'n never once after thowt yet."

17 - The Coaler

Walter Emsley 1860-1938

Emsley was a professional artist and dialect writer who grew up on the outskirts of Manchester. Through endeavour he overcame considerable difficulties in his career, and his poetry led him in time to become an established member of the Manchester Literary Club. His powerful poem,The Coaler echoes the description of Emsley as an imaginative and sincere writer.

When I was a young boy there were still two working mines in Burnley. One was Bank Hall Colliery and the other Reedley Pit. I lived near to Reedley Pit in the Barden Lane area of Burnley, and played with my friends on spare ground just on the opposite side of a railway, next to the pit. We would often watch the miners walking to and from their shift, listening to their banter and the 'clug, clank' of their heavy boots and tin cans which they usually carried.

My grand-dad on my father's side had been a miner before WW1, supporting a family of ten childen. It doesn't bear thinking about how the family would have fared without any effective form of support or compensation if he had been severely injured, or killed. As children sitting around the fire in the 1950s, when the nation was still largely dependent on coal, we could have had no idea what the real cost of coal was. The poem brings home that message. I have used the second half of the first verse as a chorus.

The Coaler

When winter comes reaund,

An' ther's frost, fog, an' snow,

When yo' shiver and shake, an'

Th' East winds keenly blow,

When yo've bin reaund wi' paper,

And stuff'd every crack,

While a blaze brightly burn,

Hauve o' th' way up th' fire back.

Chorus:

When y're whoam fra yo're wark,

An yo're toastin' yo're toes,

Wi' yo're feet upo' th' fender,

An' th' fire fairly glows,

Just yo' get out yo're bacca,

An' ponder a bit

On th' felly as fotches

Yo're coal eaut o' th' pit.

Aye! Just think o' him gooin' eawt,

Day after day,

Wi his grub in his shirt,

An' a can o' cowd tay;

Heaw he's drop'd deawn i' th' cage -

Like a bait on a line

To temp Providence wi' -

Among th' dangers o' th' mine.

Heaw he trudges along,

'Til he gets to his place,

An' its not a great while

'Til he's moppin' his face

As he lies on his back,

While his form's dimly lit,

Wi' his Davy lamp - think on him,

Deawn theer I' th' pit!

Aye! Aw ax yo' to think on him,

Grovellin' I' th' gloom

While he's hewin' - unthinkin'ly p'raps -

His own tomb!

Think o' th' floods, faa's, an fearsome

Choke damp as may come

Give a thowt to his wife's

Weary waitin' awhoam!

Don't yo' think 'at whatever he's paid,

He earns weel,

Wi' his muscles o' iron an'

Nerves mad' o' steel.

An' when rescue work's wantin' -

That's th' time he shows grit,

He's a Hero then! Him

As gets coal eawt o' th' pit!

18 - My Piece is o' bu' Woven Eawt (Weaver's Prayer)

Richard Rome Bealey 1828-1889

This is a jewel of a poem, written by Richard Rome Bealey, a master bleacher and draper who lived in Manchester. He was a dialect and temperance poet, intensely interested in literature. Like the weaver in his poem, Bealey crafted his work with tremendous care - The Weaver's Prayer was received to great acclaim. The Rev Charles Garrett, a much-loved evangelist of the time - described it as 'the best dialect poem in the country'. Bealey was the founder member and first Honorary secretary of the Manchester Literary Club.

My Piece is o' bu' Woven Eawt (Weaver's Prayer)

My "piece" is o' bu' woven eawt,

My wark is welly done;

Aw've "treddled" at it day by day,

Sin'th toime 'ut aw begun.

Aw've sat I'th loom-heawse long enough,

An' made th' owd shuttle fly;

An' neaw aw'm fain to stop it off,

An' lay my weyvin' by.

Aw dunnot know heaw th' piece is done;

Aw,m fear'd it's marr'd enough;

Bu' th' warps weren't made o' th' best o' yarn.

An' th' weft were nobbut rough.

Aw've been some bother'd neaw an' then

Wi' knots an' breakin's too;

They'n hamper'd me so mich at toimes

Aw've scarce know what to do.

Bu' th' Mester's just, an' weel He knows

'Ut th' yarn were none so good;

He winna "bate" me when when He sees

Aw'se done as weel's aw could.

Aw'se get my wage- aw'm sure o' that;

He'll gi'e me o' ut's due,

An' mebbe, in His t'other place,

Some better wark to do.

Bu' then, aw reckon, 'tisn't th' stuff

We'n getten t' put I'th loom,

Bu' what we mak' on't good or bad,

'Ut th' credit on't 'll come.

Some wark I' silk, an' other some

Ha'e cotton I' their gear;

Bu' silk or cotton matters nowt,

If nobbut th' skill be theere.

Nu' now it's nee' to th' eend o' th' week,

An' close to th' reckonin' day;

Aw'll tak my "piece" upon my back,

An' yer what Mester'll say;

An' if aw nobbut yer His voice

Pronounce my wark "weel done,"

Aw'll straight forget o'th trouble past

I' th' pleasure 'ut's begun.

Glossary:

A glossary of words used in context of the songs on this CD:

A' - of

Aboon - above

Afoor - before

Agen - again

Akin - related

Awlus - always

An' - and

Art - are you

Aw - I

Aw'm - I am

Aw'd - I had; I would

Awlus - always

Aw'st - I will

Aw've - I have

Ax - ask

Axed Axt - asked

Axing - asking

Aye - yes

Baniches - banishes

Bate - to deduct from wages

Becose - because

Bein' - being

Bi - by

Bi th' mass - as one; all together

Bi' - be

Bin - been

Bi'th - by the

Boggart - a spirit, a ghost, a scarecrow

Booath - both

Brass - money

Bu' - but

Bud - but

Buss - kiss

Ca - call

Campin' - visting

Caw - call

Ceawnted - counted

Clooas - clothes

Co'd - called

Conno' - can not

Connod - cannot

Con't - can it

Cooarted - sought out;

Coom - come

Deauce - here likely to mean 'who the devil'

Deawn - down

Dee - die

Delf - a stone or slate quarry

Dell - A small wooded hollow

Dornd - don't

Dozin - dozing or sleeping

Dree - ?

Dreeomin' - dreaming

Dunno' - do not

Dunnot - do not

Dur - door

Durn't - don't

Dusta - do you; what do you

E'en - even

Eaur - our

Eawt - out

Eawtshines - outshines

E'e - eye

E'en - even

Een - eyes

Eend - end

'Em - them

Er - her

Eytin' - eating

Fain - compelled

Feaw - ugly; fowl

Feightin' - fighting

Felly - a fellow

Fender - a guard before a fireplace hearth to confine the ashes

Feyther - father

Flounderin - floundering

Fo - fall

Foaks - folks

Foo' - fool

Fooak - folk

Fortchin' - look

Fost - first

Fra - from

Fratchin - quarrelling; quarrelsome

Fro' - from

Fun - found

Ganger - quarry overlooker

Gaumless - dull-witted

Ged - get

Geddin - getting

Geet - moved on; got on

Getten - become

Gi or gie or gi'e - give

Glib - easy, facile

Goin' - going

Goo - go

Gooin' - going

Gowd - gold

Gradely - proper

Greawnd - ground

|

Gree' - green

Groon - grown

Guid-in' glimmer - an understanding

Ha' - have

Ha'e - have

Hauve - half

Hawkin - hawking; selling

Heaw - how

Heawse - house

Hed - had

Hev - have

Hooam - home

Hond - hand

Hoo - she

Hook id off - go quickly

Hur - her

I' - in

Id - it

I'th - in the

Jink - tap

Kayther - cradle

Kissin' - kissing

Knockt off - stopped

Kornd - cannot

Laughin' - laughing

Leet - light

Leetly - lightly

Liefer - rather

List - enlist in the army

Lung - long

Luv - love

Mony - many

Mak - make

Marr'd - spoiled

Mebbe - may be

Mecks - makes

Med - made

Meetin' - meeting

Mester - Master - God in the context of the song

Met - might

Meyt - meat

Mi - my

Mich - much

Mindin' - To take care of; to watch over

Misel' - my self

Mo - me

Mon - man

Mony - many

Mooar - more

Moor - more

Mote - might

Mun - must

Neaw - now

Nee - near

Ne'er - never

Neet - night

Noan - none

Nobbut - only; nothing but

Nod - not

Nooas - nose

Nook - a corner place, a secluded retreat

Nor - than

Nother - neither

Nowe - no

Nowt - nought or nothing

Nu' - now

O - all

O' - of

O'er - over

Oather - either

Old Sol - the sun

O's - all is

Owd - old

Parchin - thirsting

Peg - leg

Piece - a complete length of cloth woven at one operation

Pipin' - piping

Pouch - pocket

Pratty - pretty

Rayther - rather

Reand - round

Reaund - round

Reddy - ready

Reet - right

Reychin' - reaching

Ruts - crevices

Scanty - scarce, rare

Scoor - score

Scotchmen - persons who place an object under a wheel to stop it rolling. In the context of this song, it appears to mean itinerant door-to-door salesmen

See'd - saw

Seet - see; started

Ses - says

Si - see

Sich - such

Sin - since

Sin - seen

|

sin' - since

Sippin' - sipping

Skeomin' - to scheme; making a plan to achieve an end or purpose

Sluchy - soft mud; sludge

Smook - smoke

Sooa - so

Spooney - loving; fawning

Spree - good time; a frolic; a drinking bout

Stir a peg - move; walk

Suckin' - sucking

Summat - something

Shuzhaew - however; anyhow

Sweear - swear

T' or th' - the

Ta - thou, you

Ta'e - take

Tackler - an overlooker in a weaving-shed

Tak - take

Tay - tea

Teawn - town

Teck - take

Th' - the

Th' or t' - the

Th' Union - A union of parishes or authorities providing workhouse facilities in their area or region

Th' reckonin' day - the time at which the weaver's cloth length is assessed for quality and payment

Thad - that

Tha'll - thou will; you will

Tha'rt - thou are

That's a througher - that's worrying, disturbing

Thee or thea - you

Theere - there

Ther - their

Ther's - there is

They'n - they have

Thi - thou; you; your

Thingammy - a something

Thine - yours

Thowt - thought

Throo' - through

Throstle - a thrush

Thur - there were

Tidy - quite some

Till - until

'Tis - it is

To boot - also

Toime - time

Torned - turned

Trudge - walk wearily

Twitchin' - to pull or draw

'Twur - it was

Ud - would

Un - and

Upo' - upon

Ut - at

'Ut - that

Var' - very

Wi - with

Wi'n - we have

Wags on - goes on; carries on

Waken - waken

Wark - work

Warkheawse - workhouse

Warp - The threads which are extended lengthwise in the weaving loom

Wayter - water

Weel - well

Weet - wet

Weft - The threads that are passed through the warp threads across the loom

Weighver - weaver

Welly - nearly; almost

Wench - woman

Wer - were

Werk - work

Weyvin - weaving

Wheer - where

Whoa - who

Whoam - home

Wi - with

Wi'n - we have

Wilt - will

Winna - will not

Wod - what

Wold - world

Wonst - once

Wortchin' - working

Wot's - what is; what are

Wouldta - would you

Wur - were

Yeards - yards

Yed - head

Yer - year

Yer - hear

Yerd - heard

Yo' - you

Yo'r - your

|

Acknowlegements:

For the instrumental accompaniament of the songs, a huge thanks to:

- Brian Ainley - fiddle

- Geoff Woolfe - mouth-organ

- Nick Woodward - cello

- John Shaw - Appalachian dulcimer

for lending their musicianship. Also my sincere thanks to John, for his unfailing enthusiasm in the work of recording these accompanied songs.

The choruses were recorded at one of the excellent evenings at the Little Vic in Stroud. For lending their voices, very many thanks to:

The choruses were recorded at one of the excellent evenings at the Little Vic in Stroud. For lending their voices, very many thanks to:

- Bob Bray

- Danny Stradling

- Viv and Roger Grimes

- Ken Langsbury

- Geoff Gillett

- Tim Normanton

- Hugh Tarran

- Chrissie Molan

A very special thankyou to Rod and Danny Stradling. The CD was made at their suggestion and with their encouragement, and most of the recordings were made around the kitchen table at their home in Stroud. A big thankyou to Rod for the work of recording and production.

Thankyou to my wife Chrissie for her unfailing support and commitment to this project, and for the editing of the notes.

Thankyou to Aunt Rose and my sister Mary for sharing their family memories.

Lancashire Libraries, particularly Burnley Library, were key in developing my interest back in the 1960s, and they have been a tremendous help ever since.

Preston and Blackburn libraries have provided invaluable help with background information about the dialect poets. A big thankyou to all.

The Lancashire Libraries, like those all over the country, perform a priceless service in helping to preserve our cultural heritage. They should be valued.

Booklet: Text by Harry Langston,

editing, DTP, printing by Rod Stradling

CDs: editing, production by Rod Stradling

A Musical Traditions Records production

© 2011

Article MT267

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 22.9.11

Many members of the family worked in the textile industry at some point in their lives, although the depression of the 1930s took some of my father's family to find work in Blackpool and the Midlands. When I was a young lad most were still living in Burnley.

Many members of the family worked in the textile industry at some point in their lives, although the depression of the 1930s took some of my father's family to find work in Blackpool and the Midlands. When I was a young lad most were still living in Burnley.

I loved music, and, lucky for me, my secondary school had a great music tradition. It had a silver band and a full orchestra. Soon I was playing a cheeky clarinet in both and a recorder in a school consort. I also joined the Boys Brigade bugle band belonging to Angle Street Chapel.

I loved music, and, lucky for me, my secondary school had a great music tradition. It had a silver band and a full orchestra. Soon I was playing a cheeky clarinet in both and a recorder in a school consort. I also joined the Boys Brigade bugle band belonging to Angle Street Chapel.

At 15, 'real life' took over. I became apprentice in a very traditional up-market high-class furnishing business, J H Hesketh and Sons of Burnley. Although I was only there for a few years, the experience made a huge impression on me. The workforce was made up of highly skilled men and women; cabinet makers, upholsterers, French polishers, soft furnishers and carpet fitters. Working with their hands, and a few pieces of cloth and wood, they created furniture and restored antiques that could (and did) grace some of the grandest homes in Lancashire.

At 15, 'real life' took over. I became apprentice in a very traditional up-market high-class furnishing business, J H Hesketh and Sons of Burnley. Although I was only there for a few years, the experience made a huge impression on me. The workforce was made up of highly skilled men and women; cabinet makers, upholsterers, French polishers, soft furnishers and carpet fitters. Working with their hands, and a few pieces of cloth and wood, they created furniture and restored antiques that could (and did) grace some of the grandest homes in Lancashire.

I'd never lost my love of playing the recorder, so I joined a consort where I sang early songs and played recorder and crumhorn. We performed everywhere, from streets to castles and medieval banquets - I've always had a streak of the showman, and I really enjoyed these. Another Bristol group got started where I sang '30s jazz numbers. At other times, I joined in with music-hall events. Looking back, I think the music experiences fed, rather than watered down my approach to traditional folk music, which has always been my central interest.

I'd never lost my love of playing the recorder, so I joined a consort where I sang early songs and played recorder and crumhorn. We performed everywhere, from streets to castles and medieval banquets - I've always had a streak of the showman, and I really enjoyed these. Another Bristol group got started where I sang '30s jazz numbers. At other times, I joined in with music-hall events. Looking back, I think the music experiences fed, rather than watered down my approach to traditional folk music, which has always been my central interest.

The orchard was given over to fire-lit dancing and games, and the barn, parlour and kitchen to song and music. Some of the country's most talented up-and-coming musicians and singers were invited along to share traditional music with the family and friends. Jim Small, a fine local singer and harmonica player from Cheddar, could sometimes be coaxed to join the 'sing' around Susie's kitchen table. Jim's quiet approach and commitment to his local material was a real inspiration, I felt he was 'the genuine article'. The Cheddar choral tradition that he had grown up with was strongly evident in his singing, and it had resonance with me.

The orchard was given over to fire-lit dancing and games, and the barn, parlour and kitchen to song and music. Some of the country's most talented up-and-coming musicians and singers were invited along to share traditional music with the family and friends. Jim Small, a fine local singer and harmonica player from Cheddar, could sometimes be coaxed to join the 'sing' around Susie's kitchen table. Jim's quiet approach and commitment to his local material was a real inspiration, I felt he was 'the genuine article'. The Cheddar choral tradition that he had grown up with was strongly evident in his singing, and it had resonance with me.

Dear Gracie, dear Gladys, dear Gertie

Dear Gracie, dear Gladys, dear Gertie

Little Jimmy Jowett

Little Jimmy Jowett

The choruses were recorded at one of the excellent evenings at the Little Vic in Stroud. For lending their voices, very many thanks to:

The choruses were recorded at one of the excellent evenings at the Little Vic in Stroud. For lending their voices, very many thanks to: