Article MT136

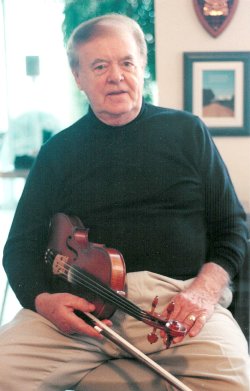

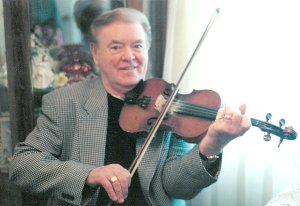

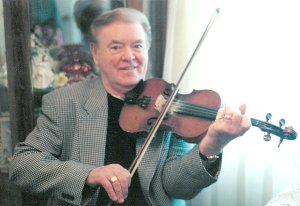

John MacDonald

Cape Breton fiddler

Inverness County, along the western side of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, represents the region where the most concentrated Gaelic settlement occurred and where fiddle music was most highly cultivated. John is one of the few living players who truly plays in the classic style of the region: with large expanses of bow, extremely pungent 'cuts' (bow triplets), an extensive use of double stops and tunes phrased to supply a lilting dance 'lift' (in contrast, most exemplars of Cape Breton fiddling familiar to outsiders play in a faster and considerably less decorated style influenced by modern folk groups with much less of the distinctively Gaelic flavoring that John supplies to his music). John's long domicile in Toronto has no doubt kept his playing closer to the older norms. Many of the neighbors he mentions in his reminiscences represent the most locally celebrated violinists of the 1930s, in a time when Gaelic still constituted the dominant language in John's locale.

Inverness County, along the western side of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, represents the region where the most concentrated Gaelic settlement occurred and where fiddle music was most highly cultivated. John is one of the few living players who truly plays in the classic style of the region: with large expanses of bow, extremely pungent 'cuts' (bow triplets), an extensive use of double stops and tunes phrased to supply a lilting dance 'lift' (in contrast, most exemplars of Cape Breton fiddling familiar to outsiders play in a faster and considerably less decorated style influenced by modern folk groups with much less of the distinctively Gaelic flavoring that John supplies to his music). John's long domicile in Toronto has no doubt kept his playing closer to the older norms. Many of the neighbors he mentions in his reminiscences represent the most locally celebrated violinists of the 1930s, in a time when Gaelic still constituted the dominant language in John's locale.

These autobiographical notes were prepared for Rounder CD 7051 Formerly of Foot Cape Road, with Doug MacPhee on piano. It is scheduled to be released in April, 2004 as a limited edition CD within Rounder's North American Traditions Series (the project was originally, intended for England's Musical Traditions label but the difficulties of getting records into Canada at a locally reasonable price forced a switch to an American release). More of John's music will later appear on Rounder 7040, Traditional Fiddle Music of Cape Breton, vol. 4. I am grateful to Rod and Danny Stradling for their assistance with the autobiography (Danny kindly transcribed the initial interviews, which I then supplemented with phone calls), as well as Doug MacPhee and Morgan MacQuarrie. For further information on the record, visit http://www.rounder.com/rounder/nat

Mark Wilson

Autobiography:

I was born in Foot Cape, Nova Scotia, a little place about two and a half miles from the little town of Inverness. It was a large family: nine brothers and four sisters.  My parents were John Angus and Katie Ann MacDonald. She was also a MacDonald before she was married. I think my father's people came from a place called Moidart. I believe it was two brothers that came and one of them landed in Pictou County and that's where my side of the family started from.

My parents were John Angus and Katie Ann MacDonald. She was also a MacDonald before she was married. I think my father's people came from a place called Moidart. I believe it was two brothers that came and one of them landed in Pictou County and that's where my side of the family started from.

I was born October 9th, 1926. That was before the Great Depression hit but, being on a farm, it was always a 'depression', so we didn't much notice the difference when it came. I'll have to say that we were very fortunate, though: we were never hungry. The butter and cheese we made ourselves. If you wanted a chicken dinner, you just went out and got one. When the day ended, you'd bring your vegetables in and put them in the mud cellar. The only thing we didn't have was too many goodies. Our grocery bill would probably be just flour, sugar, tea and molasses. Besides the farm work, my old man was a milkman; he delivered milk in Inverness. It used to come in sixteen quart cans. He would pour it from there into the quart bottle, seal it up, drop it off at the doors, but half the time somebody else come along and steal it. So that's how my dad made a living for all of us and I'm sure he had his rough days, too. And things were all very neighborly back then. It wasn't so much all the good times we had, but the hard times we went through as well. If one guy had a problem - say, if his barn burned down - there'd be fifteen neighbors over there the next day helping to build the barn back up again.

My parents mostly spoke Gaelic and the kids just picked it up from listening to them. At that time I could talk all day to anybody, it didn't matter how good their Gaelic was. There was an old lady - Mrs Campbell was her name - and she would have then been into her seventies. She never spoke a word of English. We had a blueberry field near our farm and lots of people would come by to pick blueberries. Mrs Campbell would do that and she'd always come to the house first because her and mama used to do a lot of chit-chat. But if mama wasn't home, you'd be left in the kitchen to talk to her and you had to talk Gaelic to her because she didn't understand anything else. So when the older boys would see Mrs Campbell coming, they'd all take off and leave me there. So I had a lot of Gaelic then, but you lose the language if you stop using it. For years Malcolm MacDonald and I would get on the phone and talk a lot here in Toronto, but when that ended, my Gaelic started to going to pot. I still understand a lot of it, but don't speak it too much.

I learned English in the home. Mama was good about that. I don't imagine she had too much education herself, for they were all self-taught in those days. My father couldn't have stayed at school very long but he could do a maths test quicker in his head than the older kids in grades six or seven could do with a pen and paper. But times were tough then. We were only about half a mile away from school, but I didn't start going until I was probably ten years old. We didn't have the winter clothing and shoes and there was too much snow to walk through back then. I got out of school at about sixteen. I think I got my grade eight - I was lucky to get even that back in those days.

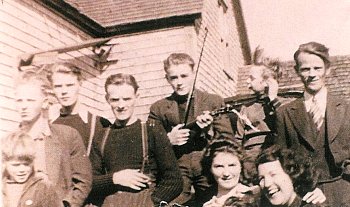

My dad didn't play any instrument but he could whistle every tune that was around or diddle the mouth music. Mother wasn't a singer but she knew all the words to most of the Gaelic songs that were around at that time. My second oldest brother used to sing a lot of Gaelic songs as well.  Then there were two older brothers I had that played violin: Lawrence and Jonas. Jonas had a great ear for music and he could just go to the dance in Kenloch three miles away and come back home with a new tune. You see, back in those days if the fiddler had learned a new tune the previous week, you'd probably hear that tune four times in the course of a night because they used to dance eight, nine, ten or eleven sets an evening and that new tune would be played a lot that night. So there wouldn't be a dance night that Jonas wouldn't come home and take the fiddle out the next day and play that new tune. Laurence had a good bow hand: he was six feet tall with long arms and long fingers, perfect for the violin. But Laurence was very shy and he'd never played for dances or places like that. He'd just take the fiddle and go in the living room by himself - no lights, of course - and he'd just play there by the hour. All but one of my brothers are all dead now, though.

Then there were two older brothers I had that played violin: Lawrence and Jonas. Jonas had a great ear for music and he could just go to the dance in Kenloch three miles away and come back home with a new tune. You see, back in those days if the fiddler had learned a new tune the previous week, you'd probably hear that tune four times in the course of a night because they used to dance eight, nine, ten or eleven sets an evening and that new tune would be played a lot that night. So there wouldn't be a dance night that Jonas wouldn't come home and take the fiddle out the next day and play that new tune. Laurence had a good bow hand: he was six feet tall with long arms and long fingers, perfect for the violin. But Laurence was very shy and he'd never played for dances or places like that. He'd just take the fiddle and go in the living room by himself - no lights, of course - and he'd just play there by the hour. All but one of my brothers are all dead now, though.

Other than that there was no real music in the background of my family. But my father used to bring a lot of violinists to the house and we were allowed to stay up until after they left. Malcolm Beaton and Sandy MacLean used to be frequent visitors to our place on the farm. Malcolm was from Strathlorne and Sandy lived practically next door and they often played at dances together. Malcolm was about fifteen years younger than Sandy and he was the bigger influence on me because he took more of an interest in me. My brothers used to hide the fiddle on me but when they would go to town I would sneak in and get it. I was probably eight or nine at the time and was just using a twig from the woods for a bow with a couple of dozen hairs from the old grey mare on it.  Malcolm noticed that and so he sat down and taught me my first tune which John Campbell later translated as 'Put Me in the Big Box' - but all we ever heard at the time was just a Gaelic name, Ciste Mhor. Then Malcolm gave me my first fiddle and bought me my first bow from the Eaton's catalog. It cost $1.98: I'll remember him doing that for me for the rest of my life. He was a very kind man and a great violinist, with a beautiful bow hand. But poor Malcolm, God rest his soul, died young - he had tuberculosis. He was in and out of the hospital and the great thing I remember about him was that he could be in the hospital for six months and be out for two or three weeks and he'd be right back playing the same as he did before he went in. He recuperated quickly and he never forgot his music while he was in there.

Malcolm noticed that and so he sat down and taught me my first tune which John Campbell later translated as 'Put Me in the Big Box' - but all we ever heard at the time was just a Gaelic name, Ciste Mhor. Then Malcolm gave me my first fiddle and bought me my first bow from the Eaton's catalog. It cost $1.98: I'll remember him doing that for me for the rest of my life. He was a very kind man and a great violinist, with a beautiful bow hand. But poor Malcolm, God rest his soul, died young - he had tuberculosis. He was in and out of the hospital and the great thing I remember about him was that he could be in the hospital for six months and be out for two or three weeks and he'd be right back playing the same as he did before he went in. He recuperated quickly and he never forgot his music while he was in there.

My mother thought Malcolm Beaton was an angel and he thought the same of my mother.

Sandy MacLean was another great fiddler and I'm sure he was the greatest influence on Malcolm as they used to play together all the time. Sandy also played beautiful slow airs which was something I can't think of Malcolm ever playing. O'er the Moor, Among the Heather was the main tune I remember with Malcolm, but even it really isn't a slow air. Sandy could put a great sound to marches, too. Lila McIsaac was his piano player and she lived about a quarter of a mile from us. Lila was very nice and a great musician - she reminds me a lot of Doug's mom, Margaret. She could anticipate what you were going to play next even before you started the tune. And she also played a lot of the melody along with the chords. I like that with Dougie, too: he plays some of the melody and then some of the chords and it breaks up the steady beat of the piano.

Sandy, Lila, Malcolm: I often wonder where all of their music came from. I believe Sandy was the only one in his family that played any music. There used to be an old guy down the road there whose name was Allan Gillis. Somebody once said that he was the one that taught Sandy to read music, but I never really knew the man although apparently he lived on the same property as we lived on. And I understand Sandy took some bowing lessons when he lived in Boston in the 'twenties. But, ever since I can remember, he always looked older, I think his hair must have been snow white by the time he was thirty years old. So I would probably be too young to really appreciate how great Sandy was when he was in his prime.

Danny Campbell was another good player in his day. The only time we'd ever see Danny was that he used to play at Kenloch. We had an old '38 Plymouth and quite a few times we'd give him a drive home to Glenora Falls with the understanding that he was going to play a tune for us on the way out. We'd give him a drive home and he never let us down, even after playing all night at the dance. John Archie MacIsaac was another good fiddler in that time from up Sight Point - he died when he was very young from a heart operation. To the best I can remember, he would be along the same style as Malcolm Beaton - they both had the long fingers and the good style and could play about anything.

And that's really about all the fiddlers there were down there at the time when I left. Allan MacDonald and his family used to live pretty near our farm but they moved away before I ever heard them. Willie Kennedy and I once played a set in Kenloch together when we were probably about seventeen years old. But the only time I'd ever see Willie was if I ran into him at a dance because we didn't have these big music concerts back in that time. They did have those little outdoor picnics in the summertime where there would be horse racing and a few games for kids to play, but, as far as music goes, there might only be a piper and a fiddler or two. They might have had a dance in the evening with a hired fiddler or two, but we weren't allowed to stay out after the sun went down.

Of course, I wasn't allowed out to the other dances until I got old enough. The first dance I ever went to I think I jumped out the bedroom window. It was Hank Snow playing at the CMBA Hall in Inverness and I got to play a set with his band. Hank was already country and western back then and we had a lot of guys around Inverness that sang western songs and played guitars. We'd all gather in a field somewhere in the evening, play fiddles and sing songs. There was a fellow named John Angus Kennedy from the Inverness Corner who was a great singer and played a great guitar, too. There was a theater in Inverness back then, but it didn't last too long because none of us had the money to go to the show. So we'd just sit on the steps and watch the girls go by ...

My father died in March of '47, and my mother followed in December, and so we all scattered after that, although a few of us tried to stay on the farm for a while. Most of us never would have left home if we could have found a job around there to earn some money, but there was no work in Cape Breton then and so just about everybody had to leave. If you were on the right side of the politics and had a job but then the government changed, you were likely to lose it: "Sorry; goodbye."

It's funny when you're young like that and you've got no money or clothes, the only thing you think of is getting the hell out so you could earn some money. So we all just took off from there and there were lots of things left in the house that we should have taken with us. The first year when I came back the old house was empty. When I went back the next year, there was nothing inside. Somebody had taken the windows and the doors; they had even ripped out the tongue and groove in the parlor. They even took the stairs out that would lead you to upstairs. My folks had had a big trunk in which I had left two good violins: the one that Malcolm Beaton had given me and one that I had gotten from my first cousin. And back in those days when you took the wool off the sheep, you shipped it over to PEI on the train and they made those heavy blankets out of it. There were probably four or five of those and so many other memories packed in that trunk. But that next year when I came back it was all gone.

Anyway, I left home when I was about twenty-one and came to New Glasgow where I worked at the Eastern Woodworkers with my brother. I stayed there for a year and then went onto Truro. I had odd jobs over there for a summer and then I got a good job there with the Department of Highways, working as a fireman, keeping the steam up in the tanks of tar so that they'd be ready in the morning for to mix the cement for the roads. But I would spend it all on taxis taking out Lillian, my wife of today. The Department had some plants back in New Glasgow, so I used to hire a taxi there and go all the way to Truro to pick up Lil, drive another twenty miles to a dance, keep the taxi waiting 'til the dance was over, and then take us all back home. So a lot of my wages went there.

Then I left there in the fall of 1949 and came to Brantford, Ontario. When I got there, I went down to good old Massey Harris looking for work (it became Massey Ferguson later on).  I was staying with two wonderful people from Sydney, John and Rita Farrell, and they said, "Whatever you do, when they ask you where you're from, don't tell them you're from Nova Scotia or you'll never get hired." That was because some of the Cape Bretoners had a habit of working in a factory for a few weeks and then getting homesick. Pretty soon they were on the train or hitchhiking back home. And I could understand that because Massey Harris was a real wake-up call for me as well, coming from the woods and then going into a factory to work. They made farm machinery and it was so noisy in there, I could hardly stand it. There'd be about twenty moulding machines on one side and they'd all be clacking at different rates. It'd be enough to drive you crazy and, after the first shift I worked there, I thought, "Well, I'm not going to last here very long." But somehow I stayed there for a year, I guess.

I was staying with two wonderful people from Sydney, John and Rita Farrell, and they said, "Whatever you do, when they ask you where you're from, don't tell them you're from Nova Scotia or you'll never get hired." That was because some of the Cape Bretoners had a habit of working in a factory for a few weeks and then getting homesick. Pretty soon they were on the train or hitchhiking back home. And I could understand that because Massey Harris was a real wake-up call for me as well, coming from the woods and then going into a factory to work. They made farm machinery and it was so noisy in there, I could hardly stand it. There'd be about twenty moulding machines on one side and they'd all be clacking at different rates. It'd be enough to drive you crazy and, after the first shift I worked there, I thought, "Well, I'm not going to last here very long." But somehow I stayed there for a year, I guess.

Lil was living there as well but she decided to come to Toronto. I had gotten tired of Bradford myself and so I came along as well. But I hated Toronto at first; it was too big - too noisy - too everything. I wasn't used to all the people and the big stores at all. Back in Inverness there was really nothing there, so when I left home, I was just as green as that house plant over there. When I got off at that station at Montreal and I'm underground: I was scared out of my mind! It was just like I was looking at the moon - we had never learned anything in school about trains and houses and stores underground. We had to change train in Montreal and get on one for Toronto but I couldn't find anybody to talk English to. Oh boy, that scared the devil out of me!

At first it was only odd jobs again: terrible jobs with small wages and no benefits. Finally I went to work at Fran's Restaurant. I was with him for about five years, doing everything from cooking to waiting on the counters and working the cash register. But then Fran decided that he was going to make me a waiter in the dining room at Youge and Eglinton. Well, coming from the farm, I was always a bit shy about meeting people, so I said, "Uh uh, that's not for me, I better pack it in." So in 1955 I went to work for Loblaw's Grocery Store where I worked for forty-three years. And I was also very fortunate because I married a good woman that worked hard all her life. Lil worked for General Motors: her last job was as a quality monitor, checking the paint on trucks, for thickness, quality, and what it looked like. And she would not let anything go by that wasn't 100% right. And so, between the two wages, we never had any problems and, from the day we married, we never had a bill overdue from day one. We have four wonderful kids and thirteen grandchildren. Three of them are in Whitby here, not far from us, and one boy lives in Ajax.

Back home, I learned a lot of the tunes that I heard around, but I didn't have that much interest in the fiddle. We had this type of wind up gramophone and when a record came out, the older boys would buy it. So we had a few of the records that Angus Allan Gilllis, Dan J Campbell and Angus Chisholm had made when they went to Montreal and we had one by Alex Gillis and his Inverness Serenaders that had come from Boston - my sister had sent it to us. Other than that, I don't remember too many fiddle records and I didn't play out too much when I was in Cape Breton. As a matter of fact, when I went to Truro, I started playing the Don Messer tunes but then I got tired of that and gave up the fiddle for about two years. When we came to Toronto, Lil got me a fiddle down at Heinl's and so I more or less got back into the Scottish end of it. Today I'll still go through the tapes I have of all the different players to pick up a new tune or two because I still love to learn new music. One thing I would have done if I'd known what I know today: I would have learned to read music. I've always had a good ear for music, but it still takes you longer to pick up a tune when you've got to have somebody else play it first.

By now I've probably played as many parties and get-togethers as any fiddler in Cape Breton. You think of any kind of party and I've played at it: weddings, funerals, going away parties, house parties, birthday parties, New Year's Eve parties - you name it. And except when I ran the dances, I've generally played for nothing, just for the love of it. If people want to hear my music, and are willing to sit there and listen or dance to it, that is all I am interested in.

I never played for dances while I was living back home. I was never one to push myself and would rather just stay in the background. Back in the 'fifties there used to be dances here and there around Toronto. A fellow named Angus MacKinnon ran dances on occasion, usually in some old school house, and I played for him a few times. Then in the early 'sixties, I believe I was one of the first to start regular dances in Toronto. There was a fellow from Middle River named Bill MacDonald who was a nice player. He was a big man that worked as a service manager for Canadian Tire.  So we teamed up, rented a hall and hired a piano player: Kay Jamieson was our first accompanist. And then later we hired Jim Delaney to play: he played for both the square sets and the round dances. And we had a guitarist and most of the time a singer: sometimes girls; sometimes guys. Liberty Hall was located in the Dundas and Keele area. It was just a small place but it had a nice feeling. There's many a Saturday night when we'd have to close the doors after letting the permitted two hundred people in.

So we teamed up, rented a hall and hired a piano player: Kay Jamieson was our first accompanist. And then later we hired Jim Delaney to play: he played for both the square sets and the round dances. And we had a guitarist and most of the time a singer: sometimes girls; sometimes guys. Liberty Hall was located in the Dundas and Keele area. It was just a small place but it had a nice feeling. There's many a Saturday night when we'd have to close the doors after letting the permitted two hundred people in.

We usually played four or five sets for an evening. Bill and I played the first year together: sometimes we'd play together and sometimes we'd play a set separately. Then Bill decided he'd like to try it on his own, so he ran the dance Friday night and I stayed on with Saturday night. But he didn't have too much luck on Friday night - it was never good for dances in Toronto because too many people worked night shift. I kept it going on Saturdays, though. But it was a little too much for me to run it by myself because I couldn't both play the fiddle and be on the floor watching out for trouble. Sandy MacIntyre had been playing guitar for me at the time but I knew he also played the fiddle, so we decided to take him in as a partner. I guess Sandy and I were together for ten or eleven years. Just like with Bill, we would alternate sets and then maybe do one together.

There's a lot of work to operating a dance - and a lot of worry, too. At times I was working three jobs at one time just to keep our heads above water. Nine to five I worked in the office at Loblaw's and then Thursday night, Friday night and Saturday, I worked in their stores. Each Saturday night we would pick up the amplifiers for our dance at about 6:30 and not get home until about 1:30 in the morning. Then get up for church the next morning. First thing you know it was Monday morning again and you were on a roll for another week. Some nights we would need to take money out of our own pockets to pay the band, but there were other evenings when we made twenty dollars and, in those days, that represented a real good night's pay. Most of the time Lil and I used whatever money we'd make for treats for the week for the kids: take them somewhere special on Sunday.

We always had a prompter at all our dances at Liberty Hall. I think the square sets lost a lot when they stopped having prompters in Cape Breton, but the young folks today wouldn't pay any attention to a prompter.  For example, there are only supposed to be four couples in a set, but when you go to a dance down home, you may have fourteen pairs in one big circle. And a fiddler gets pretty tired playing so long, I tell you: when I play a square set and the first four couples are finished, then I'm pretty finished as well. Lil and I once went to a dance in Creignish where Buddy MacMaster was playing. This crew landed in from the pulp mill in Port Hawksbury. They wore great big army boots, with mud up to here, and every one of them had been into the sauce. They all got into a big circle - it must have been eight or nine couples - and they just jumped up and down like a bunch of crazy people. I asked Buddy, "Why the hell do you keep playing for that?" and he replied, "I just close my eyes and pretend they're not there."

For example, there are only supposed to be four couples in a set, but when you go to a dance down home, you may have fourteen pairs in one big circle. And a fiddler gets pretty tired playing so long, I tell you: when I play a square set and the first four couples are finished, then I'm pretty finished as well. Lil and I once went to a dance in Creignish where Buddy MacMaster was playing. This crew landed in from the pulp mill in Port Hawksbury. They wore great big army boots, with mud up to here, and every one of them had been into the sauce. They all got into a big circle - it must have been eight or nine couples - and they just jumped up and down like a bunch of crazy people. I asked Buddy, "Why the hell do you keep playing for that?" and he replied, "I just close my eyes and pretend they're not there."

But we had damned good dances at Liberty Hall for about ten years. It seemed that everybody that came up from home, especially from the Inverness area, only needed to be in Toronto a half a day before they knew where the Liberty Hall was. In fact, that's where I first met Dougie. He came to the Hall when he moved to Toronto and we had him play a set. People are still talking about those dances today; they tell me that one of the best dances that was ever in Toronto was right there. But finally the Jehovah's Witnesses came along and bought the hall and kicked us out and so we didn't do much after that. We did go over to St Mary's Hall for a little while, but it was never the same, so we just quit. Sandy continued on for a little longer by himself. Today there's nothing regular like that going on in Toronto that I know of; just an occasional dance or concert here and there. We met a lot of nice people through running the dances over the years; it seemed like every Saturday night you meet somebody new.

Looking back at my life, if I was to do it all over again, there's not much I would change. Lil and I celebrated our fifty-second anniversary last August and I had my seventy-fifth birthday last October. And we've had a good life. As to moving back East, well, there isn't enough money in Toronto now to move me away from my kids. And we have many friends here as well. So I've no regrets about moving away from home anymore. But to go back down there in summer, oh yeah - my goodness, Cape Breton's a beautiful country. And I love small towns: the nice little restaurants where everybody's so friendly and they recognize you the second time you go back in. So I just love going down home in the summer. There's no immediate family left on the island anymore, just a few nieces and nephews. I don't do a heck of a lot when I go back. Maybe a friend and I might sit up on the hill with a bottle of Keats, looking over the town of Inverness, and talk about old times.

John L MacDonald - 2.3.04

Article MT136

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 2.3.04

Inverness County, along the western side of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, represents the region where the most concentrated Gaelic settlement occurred and where fiddle music was most highly cultivated. John is one of the few living players who truly plays in the classic style of the region: with large expanses of bow, extremely pungent 'cuts' (bow triplets), an extensive use of double stops and tunes phrased to supply a lilting dance 'lift' (in contrast, most exemplars of Cape Breton fiddling familiar to outsiders play in a faster and considerably less decorated style influenced by modern folk groups with much less of the distinctively Gaelic flavoring that John supplies to his music). John's long domicile in Toronto has no doubt kept his playing closer to the older norms. Many of the neighbors he mentions in his reminiscences represent the most locally celebrated violinists of the 1930s, in a time when Gaelic still constituted the dominant language in John's locale.

Inverness County, along the western side of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, represents the region where the most concentrated Gaelic settlement occurred and where fiddle music was most highly cultivated. John is one of the few living players who truly plays in the classic style of the region: with large expanses of bow, extremely pungent 'cuts' (bow triplets), an extensive use of double stops and tunes phrased to supply a lilting dance 'lift' (in contrast, most exemplars of Cape Breton fiddling familiar to outsiders play in a faster and considerably less decorated style influenced by modern folk groups with much less of the distinctively Gaelic flavoring that John supplies to his music). John's long domicile in Toronto has no doubt kept his playing closer to the older norms. Many of the neighbors he mentions in his reminiscences represent the most locally celebrated violinists of the 1930s, in a time when Gaelic still constituted the dominant language in John's locale.

My parents were John Angus and Katie Ann MacDonald. She was also a MacDonald before she was married. I think my father's people came from a place called Moidart. I believe it was two brothers that came and one of them landed in Pictou County and that's where my side of the family started from.

My parents were John Angus and Katie Ann MacDonald. She was also a MacDonald before she was married. I think my father's people came from a place called Moidart. I believe it was two brothers that came and one of them landed in Pictou County and that's where my side of the family started from.

Then there were two older brothers I had that played violin: Lawrence and Jonas. Jonas had a great ear for music and he could just go to the dance in Kenloch three miles away and come back home with a new tune. You see, back in those days if the fiddler had learned a new tune the previous week, you'd probably hear that tune four times in the course of a night because they used to dance eight, nine, ten or eleven sets an evening and that new tune would be played a lot that night. So there wouldn't be a dance night that Jonas wouldn't come home and take the fiddle out the next day and play that new tune. Laurence had a good bow hand: he was six feet tall with long arms and long fingers, perfect for the violin. But Laurence was very shy and he'd never played for dances or places like that. He'd just take the fiddle and go in the living room by himself - no lights, of course - and he'd just play there by the hour. All but one of my brothers are all dead now, though.

Then there were two older brothers I had that played violin: Lawrence and Jonas. Jonas had a great ear for music and he could just go to the dance in Kenloch three miles away and come back home with a new tune. You see, back in those days if the fiddler had learned a new tune the previous week, you'd probably hear that tune four times in the course of a night because they used to dance eight, nine, ten or eleven sets an evening and that new tune would be played a lot that night. So there wouldn't be a dance night that Jonas wouldn't come home and take the fiddle out the next day and play that new tune. Laurence had a good bow hand: he was six feet tall with long arms and long fingers, perfect for the violin. But Laurence was very shy and he'd never played for dances or places like that. He'd just take the fiddle and go in the living room by himself - no lights, of course - and he'd just play there by the hour. All but one of my brothers are all dead now, though.

Malcolm noticed that and so he sat down and taught me my first tune which John Campbell later translated as 'Put Me in the Big Box' - but all we ever heard at the time was just a Gaelic name, Ciste Mhor. Then Malcolm gave me my first fiddle and bought me my first bow from the Eaton's catalog. It cost $1.98: I'll remember him doing that for me for the rest of my life. He was a very kind man and a great violinist, with a beautiful bow hand. But poor Malcolm, God rest his soul, died young - he had tuberculosis. He was in and out of the hospital and the great thing I remember about him was that he could be in the hospital for six months and be out for two or three weeks and he'd be right back playing the same as he did before he went in. He recuperated quickly and he never forgot his music while he was in there.

Malcolm noticed that and so he sat down and taught me my first tune which John Campbell later translated as 'Put Me in the Big Box' - but all we ever heard at the time was just a Gaelic name, Ciste Mhor. Then Malcolm gave me my first fiddle and bought me my first bow from the Eaton's catalog. It cost $1.98: I'll remember him doing that for me for the rest of my life. He was a very kind man and a great violinist, with a beautiful bow hand. But poor Malcolm, God rest his soul, died young - he had tuberculosis. He was in and out of the hospital and the great thing I remember about him was that he could be in the hospital for six months and be out for two or three weeks and he'd be right back playing the same as he did before he went in. He recuperated quickly and he never forgot his music while he was in there.

I was staying with two wonderful people from Sydney, John and Rita Farrell, and they said, "Whatever you do, when they ask you where you're from, don't tell them you're from Nova Scotia or you'll never get hired." That was because some of the Cape Bretoners had a habit of working in a factory for a few weeks and then getting homesick. Pretty soon they were on the train or hitchhiking back home. And I could understand that because Massey Harris was a real wake-up call for me as well, coming from the woods and then going into a factory to work. They made farm machinery and it was so noisy in there, I could hardly stand it. There'd be about twenty moulding machines on one side and they'd all be clacking at different rates. It'd be enough to drive you crazy and, after the first shift I worked there, I thought, "Well, I'm not going to last here very long." But somehow I stayed there for a year, I guess.

I was staying with two wonderful people from Sydney, John and Rita Farrell, and they said, "Whatever you do, when they ask you where you're from, don't tell them you're from Nova Scotia or you'll never get hired." That was because some of the Cape Bretoners had a habit of working in a factory for a few weeks and then getting homesick. Pretty soon they were on the train or hitchhiking back home. And I could understand that because Massey Harris was a real wake-up call for me as well, coming from the woods and then going into a factory to work. They made farm machinery and it was so noisy in there, I could hardly stand it. There'd be about twenty moulding machines on one side and they'd all be clacking at different rates. It'd be enough to drive you crazy and, after the first shift I worked there, I thought, "Well, I'm not going to last here very long." But somehow I stayed there for a year, I guess.

So we teamed up, rented a hall and hired a piano player: Kay Jamieson was our first accompanist. And then later we hired Jim Delaney to play: he played for both the square sets and the round dances. And we had a guitarist and most of the time a singer: sometimes girls; sometimes guys. Liberty Hall was located in the Dundas and Keele area. It was just a small place but it had a nice feeling. There's many a Saturday night when we'd have to close the doors after letting the permitted two hundred people in.

So we teamed up, rented a hall and hired a piano player: Kay Jamieson was our first accompanist. And then later we hired Jim Delaney to play: he played for both the square sets and the round dances. And we had a guitarist and most of the time a singer: sometimes girls; sometimes guys. Liberty Hall was located in the Dundas and Keele area. It was just a small place but it had a nice feeling. There's many a Saturday night when we'd have to close the doors after letting the permitted two hundred people in.

For example, there are only supposed to be four couples in a set, but when you go to a dance down home, you may have fourteen pairs in one big circle. And a fiddler gets pretty tired playing so long, I tell you: when I play a square set and the first four couples are finished, then I'm pretty finished as well. Lil and I once went to a dance in Creignish where Buddy MacMaster was playing. This crew landed in from the pulp mill in Port Hawksbury. They wore great big army boots, with mud up to here, and every one of them had been into the sauce. They all got into a big circle - it must have been eight or nine couples - and they just jumped up and down like a bunch of crazy people. I asked Buddy, "Why the hell do you keep playing for that?" and he replied, "I just close my eyes and pretend they're not there."

For example, there are only supposed to be four couples in a set, but when you go to a dance down home, you may have fourteen pairs in one big circle. And a fiddler gets pretty tired playing so long, I tell you: when I play a square set and the first four couples are finished, then I'm pretty finished as well. Lil and I once went to a dance in Creignish where Buddy MacMaster was playing. This crew landed in from the pulp mill in Port Hawksbury. They wore great big army boots, with mud up to here, and every one of them had been into the sauce. They all got into a big circle - it must have been eight or nine couples - and they just jumped up and down like a bunch of crazy people. I asked Buddy, "Why the hell do you keep playing for that?" and he replied, "I just close my eyes and pretend they're not there."