Article MT297

When Cecil Left the Mountains - Part 2

More early recordings of American music

In When Cecil Left the Mountains (MT article 255) I tried to explain how, shortly after Cecil Sharp left the Appalachian Mountains of eastern America, recording companies began recording and issuing 78rpm discs of music from the Appalachians. I gave examples of both Old-World Child and broadside ballads which had been recorded commercially. I will continue to give similar examples in Part 2, but will also mention Old-World influences on fiddle music and will try to show how some 'Appalachian' songs evolved out of earlier Old-World pieces.

On Sunday August 9th, 1942, song collectors Alan Lomax, John W Work and Lewis Jones were in the Mississippi Delta town of Clarksdale in Coahoma County, the home of numerous blues singers, including McKinley Morganfield, better known today as Muddy Waters. It is also the place where Bessie Smith died in 1937, following an automobile crash on nearby Highway 61. One singer that Lomax and his friends met that day was called Will Starks. According to Work:

Will Starks has been living in the bottoms (his name for the Delta) all of his life. He was born on a plantation near Sardis in 1875. His father was a ballad singer, a fiddler, and banjo player. Will early learned to play the banjo, and listening to his father, he learned many songs. He next learned to play the "autoharp", an instrument of twenty- eight strings. On it and on the accordion, which he next learned to play, the tunes were the same as those played on the banjo: "Billy in the Low Ground", "Arkansas Traveller", and the like, as well as the current ballads. Much later in his life he learned to play the guitar, this became his favourite instrument. For many years he played for plantation dances.

When a young man, he left the plantation to work at sawmills. As one sawmill would close down, he would work at another. When no sawmill was in operation, he usually went to work on levee camp jobs. All of these jobs provided temporary living quarters for the workers. The sawmill quarters were usually shanties, while the levee quarters were frequently tents - individual tents for a man and wife, large tents called "bull pens" for groups of single men. The after-work hours in these quarters were filled with recreation of varying degrees of interest. The most important of these recreational pursuits, from the standpoint of the folklorist, were the informal small scale recitals that the guitar, harmonica, and fiddle players gave on the steps of their shanties, or on stools in front of their tents. The workmen, mostly itinerants, came from many different places bringing with them the songs, stories, and unique folkways of their widely separated localities.

Work added that almost all of Will Starks' songs and ballads were picked up in sawmill shanties during the period 1886 - 1920. There was, however, one notable exception, and this was a song that his father had taught him. Will, or perhaps Alan Lomax, called it The Fox Hunter's Song; whilst in England it has often been noted as The Noble Foxhunting (Roud 584). According to the song collector the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 - 1924), who collected a version which later appeared in his Songs of the West as The Duke's Hunt, 'This is a mere cento from a long ballad, entitled The Fox Chase, narrating a hunt by Villiers, second duke of Buckingham, in the reign of Charles II. It is in the Roxburgh Collection and was printed by W Oury, circa 1650.' How, one might ask, did an English song from the middle of the 17th century end up on the lips of the son of a Mississippi slave? 1 Did white plantation owners organise foxhunts across their lands? And, if so, could this song have survived because of this? Or was it simply chance that the song had been taken to Mississippi and remembered by Will Stacks and his father? I don't suppose that we will ever know. But such things did happen.

1 Did white plantation owners organise foxhunts across their lands? And, if so, could this song have survived because of this? Or was it simply chance that the song had been taken to Mississippi and remembered by Will Stacks and his father? I don't suppose that we will ever know. But such things did happen.

In 1894 the folklorist Joseph Jacobs (1854 - 1916) published a collection of folktales under the title More English Fairytales. One story, titled The Golden Ball, tells of a fiancé who has to find a golden ball so that he may save his girlfriend from the gallows. In other versions of the story the girl is about to be hanged because she has lost some object or other that is made of gold. Folklorists have spent decades trying to figure out just what the golden ball represents. This tale also exists as a balled, one which Professor Francis Child called The Maid Freed from the Gallows (Child 95, Roud 144), while English folksingers call it The Prickle Holly Bush. Like many ballads, such as The Fox Hunter's Song, The Maid Freed from the Gallows, also crossed over the Atlantic and this version was recorded commercially in 1937 by the great singer Huddie 'Leadbelly' Ledbetter.

The Gallis Pole

Father, did you bring me the silver

Father, did you bring me any gold?

What did you bring me, dear father

Keep me from the gallis pole?

Yeah, what did you?

Yeah, what did you?

What did you bring me, keep me from the gallis pole?

Spoken: In olden times years ago, when you put a man in prison behind the bars in a jailhouse, if you had fifteen, or twenty-five, or thirty dollars you could save him from the gallis pole, 'cause they gonna hang him if you don't bring up a little money. Everybody would come to the jailhouse and boy would ran upside the jail; he was married, too. As for who brang him something, lot of comfort, here comes his mother.

Mother, did you bring me the silver

Mother, did you bring me any gold?

What did you bring me, dear mother

Keep me from the gallis pole?

Yeah, what did you?

Yeah, what did you?

What did you bring me, keep me from the gallis pole?

Son, I brought you some silver

Son, I brought you some gold

Son, I brought you a little of everything

Keep you from the gallis pole

Yeah, I brought it

Yeah, I brought it

I brought you, keep you from the gallis pole

Spoken: Here come his wife. His wife brought all kind of clock parts and trace change. Everything in the world she could to get him out of the jailhouse.

Wife, did you bring me the silver

Wife, did you bring me any gold?

What did you bring me, dear wifey

Save me from the gallis pole?

Yeah, what did you?

Yeah, what did you?

What did you bring me, keep me from the gallis pole?

Friends, did you bring me the silver

Friends, did you bring me any gold?

What did you bring me, my dear friends

Keep me from the gallis pole?

Yeah, what did you?

Yeah, what did you?

What did you bring me, keep me from the gallis pole? 2

2

At times it is hard to say whether Huddie was singing the word gallis or gallows. Strange as it might seem, the ballad resurfaced in 1970, recorded as Gallows Pole on the album Led Zeppelin lll, although Bob Dylan had, by this time, also recorded his own idiosyncratic version of the story, which he titled Seven Curses. 3

3

Another British, or in this case English, song which deals with a man facing death on the gallows is that of Jack Hall (Roud 369). According to Frank Kidson, the pioneer of folksong study: 'Jack Hall was a chimney sweep, who was executed for burglary in 1701. He had been sold when a child to a chimney sweeper for a guinea and was quite a young man when Tyburn claimed him'. Roy Palmer - a latter-day Kidson - was able to expand the story in his book The Sound of History which was printed in 1988. 'Jack or John Hall ... was born of poor parents who lived in a court off Grays Inn Road, London, and who sold him for a guinea at the age of 7 to be a climbing boy. Readers of Charles Kingsley's Water Babies (1863) will know how such boys (and girls) swept chimneys by scrambling up inside them. The young Hall soon ran away from this disagreeable occupation, and made a living as a pickpocket. Later he turned to housebreaking, for which he was whipped in 1692 and sentenced to death in 1700. He was reprieved, then released, but returned to crime and was re-arrested in 1702 for stealing luggage from a stagecoach. This time, he was branded on the cheek and imprisoned for two years. Finally, having been taken in the act of burgling a house in Stepney, he was hanged at Tyburn on 17 December 1707.'

In the 1840s a Music Hall singer W G Ross revised the song, changing the name to Sam Hall in the process. On 10 March 1848 Percival Leigh noted the following account of an evening's entertainment in an early Music Hall:

'After that, to supper at the Cider Cellars in Maiden Lane, wherein was much Company, great and small, and did call for Kidneys and Stout, then a small glass of Aqua-vitae and water, and thereto a Cigar. While we supped, the Singers did entertain us with Glees and comical Ditties; but oh, to hear with how little wit the young sparks about town were tickled! But the thing that did most take me was to see and hear one Ross sing the song of Sam Hall the chimney-sweep, going to be hanged: for he had begrimed his muzzle to look unshaven, and in rusty black clothes, with a battered old Hat on his crown and a short Pipe in his mouth, did sit upon the platform, leaning over the back of a chair: so making believe that he was on his way to Tyburn. And then he did sing to a dismal Psalm-tune, how that his name was Sam Hall and that he had been a great Thief, and was now about to pay for all with his life; and thereupon he swore an Oath, which did make me somewhat shiver, though divers laughed at it. Then, in so many verses, how his Master had badly taught him and now he must hang for it: how he should ride up Holborn Hill in a Cart, and the Sheriffs would come and preach to him, and after them would come the Hangman; and at the end of each verse he did repeat his Oath. Last of all, how that he should go up to the Gallows; and desired the Prayers of his Audience, and ended by cursing them all round. Methinks it had been a Sermon to a Rogue to hear him, and I wish it may have done good to some of the Company. Yet was his cursing very horrible, albeit to not a few it seemed a high Joke; but I do doubt that they understood the song.'

Ross's 'dismal Psalm-tune' - used by traditional singers such as Walter Pardon and Gordon Hall - has been on the go for at least three hundred years and has done service for such songs as William Kidd, The Praties They Grow Small, Aikendrum and the hymn Wondrous Love. 4 The song has a special place in my memory. It was the first song that I heard Walter Pardon sing. Walter sang the piece in an almost gentle and sympathetic manner. Not so Gordon Hall. I doubt if anyone who saw Gordon's presentation of this song will ever forget the occasion. Gordon, a large-built man, almost took on the persona of Sam Hall as he stared defiantly at the audience, almost spitting the words at them. And when he reached the chorus words - Damn your eyes! - he would stab at his own eyes with the fingers of his right hand. I sometimes wondered if, on reaching the end of the song, some members of the audience would be unable to decide whether or not to applaud … or else to run for their lives, especially after hearing this final verse:

4 The song has a special place in my memory. It was the first song that I heard Walter Pardon sing. Walter sang the piece in an almost gentle and sympathetic manner. Not so Gordon Hall. I doubt if anyone who saw Gordon's presentation of this song will ever forget the occasion. Gordon, a large-built man, almost took on the persona of Sam Hall as he stared defiantly at the audience, almost spitting the words at them. And when he reached the chorus words - Damn your eyes! - he would stab at his own eyes with the fingers of his right hand. I sometimes wondered if, on reaching the end of the song, some members of the audience would be unable to decide whether or not to applaud … or else to run for their lives, especially after hearing this final verse:

This will be my funeral knell to you all, to you all

This will be my funeral knell to you all

This will be my funeral knell and I'll see you all in Hell

And I hope you sizzle well, says Sam Hall, says Sam Hall

I hope you sizzle well, says Sam Hall

Versions of Jack/Sam Hall have also turned up in America. This version, Ethan Lang, was one of several dozen songs which Emry Arthur (1902 - 1967) recorded in 1928. Arthur was, perhaps, best known for being the first person to record the song I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow. He was originally from Wayne County in Kentucky and he accompanied himself on guitar, although a childhood accident meant that he was missing a finger on his left-hand and could only play rather rudimentary chords behind his singing.

Ethan Lang 5

5

My name is Ethan Lang, Ethan Lang

My name is Ethan Lang, Ethan Lang

My name is Ethan Lang, I'm the leader of the gang

And they say that I must hang, dang their eyes

I killed a man they said, so they said (x2)

I killed a man they said, when I hit him on the head

And I left him there for dead, dang his eyes

The judge said I must pay, I must pay (x2)

The judge said I must pay, for the life I took away

Now I'm facing judgement day, dang your eyes

They put me in the jail, in the jail (x2)

They put me in the jail, fed me from an iron pail

With no-one to go my bail, dang their eyes

The sheriff brought the rope, brought the rope (x2)

The sheriff brought the rope and he sprung his deathly joke

And he said "I hope you choke", dang his eyes

The jailer he came to, he came to (x2)

The jailer he came to and he brought his (blessed?) crew

For their bloody work to do, dang their eyes

The preacher he did come, he did come (x2)

The preacher he did come and he looked so awful glum

When he talked of kingdom come, dang his eyes

Oh my sweetheart will be there, will be there (x2)

Oh my sweetheart will be there, she's the only one who cares

When I'm swinging in the air, dang your eyes

Now I've bid my last farewell, last farewell (x2)

Now I've bid my last farewell and this story you can tell

How I cursed you as I fell, dang your eyes

Bearing in mind the crude nature of some English versions of this song, one can only suggest that some of the lines sung here by Emry Arthur had been edited for a more general audience.

I mentioned that The Fox Hunter's Song had appeared on mid-17th century broadside in England. Another song that Emry Arthur recorded was almost as old. Emry called the song Wandering Gypsy Girl and, as The Gypsy's Wedding Day, it had appeared on an English broadside during the early 1700s. It was reprinted frequently up to the 1880s when the Such family of south London included it in their series of songsters. The song is number 229 in the Roud Index and it has remained popular with English singers well into the late 20th century. 6 The North Carolina singer Charlie Poole also recorded a version of the song in 1930, two years after Emry Arthur's version appeared on record, and it is interesting to see how their two texts differed.

6 The North Carolina singer Charlie Poole also recorded a version of the song in 1930, two years after Emry Arthur's version appeared on record, and it is interesting to see how their two texts differed.

Wandering Gypsy Girl (Emry Arthur)

My father was a captain of a gypsy tribe, you know

My mother she gave me some counting to do

With a knapsack on my shoulder I'll bid you all farewell

I'll take a trip to London, some fortunes to tell

Some fortunes to tell, some fortunes to tell

I'll take a trip to London, some fortunes to tell

As I went a-walking all down the London street

A handsome young lawyer was the first I chanced to meet

Was the first I chanced to meet, was the first I chanced to meet

A handsome young lawyer was the first I chanced to meet

He viewed my pretty little brown cheeks, was the ones he loved so well

Said, You are a little gypsy girl will you my fortune tell?

Will you my fortune tell? Will you my fortune tell?

You are a little gypsy girl will you my fortune tell?

Oh yes, sir, oh please, sir, hold out to me your hand

You have many fine fortunes in a far-off distant land

In a far-off distant land, in a far-off distant land

You have many fine fortunes in a far-off distant land

You've courted many fair ladies but you've laid them all aside

And I'm a little gypsy girl, I'm the one to be your bride

I'm the one to be your bride, I'm the one to be your bride

I'm a little gypsy girl, I'm the one to be your bride

He took me, he led me to his house on yonder shore

While servants stood waiting to open wide the door

To open wide the door, to open wide the door

While servants stood waiting to open wide the door

The bells they did ring and the music it did play

It was a celebration of a gypsy's wedding day

Of a gypsy's wedding day, of a gypsy's wedding day

It was a celebration of a gypsy's wedding day

Oh once I was a gypsy girl but now I'm a rich man's bride

With servants to wait on me while in my carriage ride

While in my carriage ride, while in my carriage ride

With servants to wait on me while in my carriage ride

| |

My Gypsy Girl (Charlie Poole)

Once I was a gypsy girl but now I'm a rich man's bride

With servants to wait on me while in my carriage ride

While in my carriage ride, while in my carriage ride

With servants to wait on me while in my carriage ride

When I was strolling one day down London Street

A handsome young squire was the first I chanced to meet

He viewed my pretty brown cheeks which now he loves so well

He says, You, my gypsy gal, will you my fortune tell?

Will you my fortune tell? Will you my fortune tell?

He says, My little gypsy girl, will you my fortune tell?"

Yes, sir, kind sir, please hold to me your hand

You have many fine mansions in a many foreign land

But all those fine young ladies, you'll cast them all aside

I am the gypsy girl who is to be your bride

Who is to be your bride, who is to be your bride

I am the gypsy girl who is to be your bride

He took me, he led me to a pleasant quiet shore

With servants to wait on me and open my own door

And open my own door, and open my own door

With servants to wait on me and open my own door

|

Both Wandering Gypsy Girl and My Gypsy Girl can be easily traced to English broadsides, as can this song, The Soldier and the Lady (Roud 140), which the Coon Creek Girls recorded for Vocalion in 1938.

The Soldier and the Lady

'Twas early one morning, one morning in May

I saw a young couple, a-wandering their way

One was a lady, as fair as you'd see

And the other was a soldier, and a brave lad was he

Said the soldier to the lady, Oh, where are you going?

Just down by the (arches/archers?) that stand by the stream

Just down by the (arches/archers?) just down by the stream

To see the water sliding, hear the nightingales sing

They had not been there but one hour or two

When out of his satchel, a fiddle he drew

He played a message that made the hills ring

Hark, hark, said the lady, hear the nightingales sing

Said the lady to the soldier, will you marry me?

Oh no, said the soldier, that never can be

I've a wife in Columbus and children I've three

One wife is a-plenty, too many for me

Young ladies, young ladies, take warning from me

Don't place your affection on a soldier so free

Don't place your affection on a soldier so free

If you do, he'll deceive you, like mine has done me

I do wonder if the Coon Creek Girls were aware of the symbolism in this song. Or, for that matter, was the record company aware? The record was issued in the main catalogue and was not an 'under the counter' or 'party' issue. In 1956 the English song collector Peter Kennedy collected a version of the song from two elderly singers in Oxfordshire and Alan Lomax noted a longer version three years later from Jimmy Driftwood's father, Neil Morris, of Timbo, Arkansas. 7 According to Morris:

7 According to Morris:

This song, I learned from my grandmother, and I know that head (?) from my grandmother came from Scotland. And that's why I know that she learned it from her grandmother. And her grandmother learnt it from her grandmother. That's the way she told it to me when I was a child. So this is another Scottish ballad beyond a reasonable doubt, in my way of seeing it. I know it is, according to tradition.

What interests me here is not the number of grandmothers involved, but, rather, just how much justification the singer gets from such genealogical information. It tells him exactly who he is, where he comes from, how he fits into his community and why his songs are important both to him and to his neighbours. It is, as Mark Wilson once noted in a slightly different context, the quality of thought that lies behind the singing. 8

8

The Soldier and the Lady has, as I said, a well-known history. However, other early Appalachian commercial recordings are not that easy to place. In 1928 G B Grayson & Henry Whitter travelled from the mountains to New York City, where they recorded a number of songs including one which they called Where Are You Going Alice? The song, set to a tune which seems to be related to a number of older British melodies, comprises four verses, the final two being similar to verses found in the song The Banks of Claudy (Roud 266). Compare, for example, these two verses from the version of The Banks of Claudy as sung by the Copper family of Sussex 9:

9:

When Betsy heard this dreadful news, she fell into despair

In a-wringing of her hands and a-tearing of her hair.

"Since Johnny has gone and left me, no man on earth I'll take.

Down in some lonesome valley I'll wander for his sake."

Young Johnny hearing her say so, he could no longer stand.

He fell into her arms, crying, "Betsy, I'm the man.

I am that faithful young man and whom you thought was slain,

And since we met on the Claudy Banks, we'll never part again."

They are, of course, similar to verses three and four of the Grayson & Whitter text. And the line "Where are you going Alice, this dark and rainy night?" is similar to this line, again from the Copper Family version, "How far have you to travel this dark and rainy night?". The Grayson & Whitter song is, I would suggest, indeed a version of The Banks of Claudy albeit one in which the story has become condensed and one where some of the lines have become confused. Although The Banks of Claudy began life in the Old World, some later American printers did issue the words on American broadsides, and it may be that this is how the song entered the Appalachian repertoire

This is the text to the Grayson & Whitter song:

Where Are You Going Alice?

Where are you going Alice, my own heart's delight?

Where are you going Alice, this dark and rainy night?"

"Down in yonder city, my attention does remain

Looking for a young man, Sweet William is his name"

"Never mind young William, he will not meet you there

Never mind young William, he will not meet you there

Never mind young William, he will not meet you there

Just stay with me in Greenland(s), no danger need you fear"

When she heard this sad news, she fell into despair

Wringing her hands and tangling her hair

"If Willie he is drown-ded no other will I seek

Through lonesome groves and valleys I'll wander for his sake"

When he heard this sad news he could no longer stand

Took her in his arms, "Little Alice, I'm the man

Little Alice I'm the young man that's caused you all this pain

But now we've met in Greenland(s), we'll never part again" 10

10

Greenland(s), mentioned in verses 2 and 4, is probably Greenland, Tennessee, which lies on the Lee Highway, to the west of Kingsport, between Church Hill and Surgoinsville. A year later, in 1929, Grayson & Whitter recorded an instrument side, Going Down the Lee Highway, which commemorates the road mentioned above. 11

11

On Monday, August 1, 1927 a group of musicians who called themselves the Bull Mountain Moonshiners took part in the famous 'Bristol Sessions'. They recorded two pieces, although only one song was actually issued. This was a version of the old British army piece The Girl I Left Behind Me Roud 262), which the Moonshiner's called Johnny Goodwin.  Actually, although the British claim this song, usually under the title Brighton Camp which can be traced to the 1750s, the Irish believe it to be an Irish piece, An Spailpin Farnach (The Rambling Labourer), which can also be dated to the 18th century.

Actually, although the British claim this song, usually under the title Brighton Camp which can be traced to the 1750s, the Irish believe it to be an Irish piece, An Spailpin Farnach (The Rambling Labourer), which can also be dated to the 18th century.

The band was led by fiddler Charles McReynolds, who was the grandfather of bluegrass musicians Jim and Jessie McReynolds. The Girl I Left Behind Me was a highly popular tune in the mountains and more than 15 recordings were made by Old-Timey musicians prior to 1942. However, the Moonshiner's version contains a set of verses. Sadly, it has proved almost impossible to make out the words on this recording, although, judging by what can actually be heard, it may be that the verses are local to the singer's home area, rather than being traditional verses from Britain. 12

12

Some songs can be even more confusing. Consider, for example, the song Jimmie and Sallie which was recorded in 1938 by Howard and Dorsey Dixon, two mill-workers from North Carolina. 13

13

Jimmie and Sallie

Jimmie and Sallie they had a quarrel one day

Jimmie caught a freight and he rambled far away

Jimmie left Sallie one bright summer day

Not dreaming of the (vanity?) that he would have to pay

Sallie gathered flowers and made her a bed

The fairest of lilies she placed all under her head

Jimmie repented, returned home again

To find his little sweetheart and cover up his sins

Come all young true lovers, whoever you may be

Please don't condemn your sweetheart so quickly like me

For when you find out it was you in the wrong

I'm sure you'll remember the words of my song

When Jimmie came back he found Sallie was dead

Five hundred bright tears, then poor Jimmie he did shed

Jimmie, Oh Jimmie don't bear her in mind

There's other young maidens as good and as kind

There's other young maidens but none of them for me

For death has departed sweet Sallie from me

And I'll soon be leaving, to come back no more

We will be united on Heaven's golden shore

Come all young true lovers, whoever you may be

Please don't condemn your sweetheart so quickly like me

For when you find out it was you in the wrong

I'm sure you'll remember the words of my song

Where, I wonder, does this song come from? Is it British or an American song? Some of the words and phrases suggest an Old World connection, (the names Jimmie and Sallie (or Sally) certainly occur in a number of British broadside songs), although other words (caught a freight, for example) suggest a New World origin. Alternately, it could be that the song was created in America, although based on a British song. The song was recorded on September 25th, 1938; interestingly the next song that they recorded was a version of the old Child ballad of George Collins (Child 42, Roud 147). 14

14

The Story of George Collins

George Collins rode out on a winter night

He rode through the snow so wide

And when George Collins returned back home

He was taken sick and died

His little Mamie was in her room

Sewing on her wedding gown

But when she heard that George was dead

She threw all her sewing down

She sobbed and sighed, she mourned and cried

As she entered in the chambry of death

Oh George, oh George you're all my heart

Now I have nothing left

Open up his coffin, push back the lid

Undo those sheets so fine

And let me kiss his cold, cold lips

For I'm sure they'll never kiss mine

She lingered there near his body all night

Then she parted to the grave

And when those cold, cold clods was heard

Oh how little Mamie did rave

Oh Mamie, oh Mamie, don't weep, don't mourn

There's other young men as kind

Yes, mother, I know there's other young men

But no one can never be mine

Now don't you see that little dove

He's flying from pine to pine

He's mourning for his own true love

So please let me mourn for mine

The golden sun sinking in the west

Just at the close of day

And there in his last place of rest

They laid her George away

For some reason or other this ballad was recorded by quite a number of American singers during the 1920s and '30s, although not all of these recordings were actually issued. In 1926 Henry Whitter (the same person who later recorded the song WhereAre You Going Alice?) recorded a version of George Collins for the Okeh Record Company. This recording was unissued. In 1929 both Elmer Bird and Dillard Smith recorded the song for the Gennett Company and in 1931 Jesse Johnston also recorded a version for Gennett. In all three cases the song remained unissued. Perhaps the people at Gennett disliked the song! The first recording to actually appear for sale was that made in 1928 by Roy Harvey and the North Carolina Ramblers. 15 The song was issued by Brunswick Records (Br250) and was backed with a song about a local murder, The Bluefield Murder. Emry Arthur, mentioned above in connection with the song Ethan Lang, recorded George Collins a year or so after Roy Harvey's version appeared. Coincidentally, Arthur's version, on Paramount Records Pm 3222, was also backed with The Bluefield Murder. Recordings by the North Carolina Ramblers were selling well, and it may be that Arthur was trying to cash in one their popularity.

15 The song was issued by Brunswick Records (Br250) and was backed with a song about a local murder, The Bluefield Murder. Emry Arthur, mentioned above in connection with the song Ethan Lang, recorded George Collins a year or so after Roy Harvey's version appeared. Coincidentally, Arthur's version, on Paramount Records Pm 3222, was also backed with The Bluefield Murder. Recordings by the North Carolina Ramblers were selling well, and it may be that Arthur was trying to cash in one their popularity.

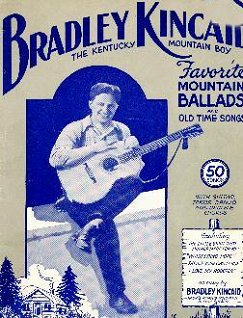

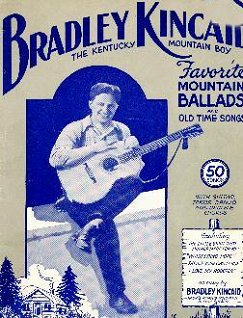

One singer who did not record a version of George Collins, a surprising fact when we consider just what he did record, was the singer Bradley Kincaid (1895 - 1991). Kincaid came from Kentucky farming stock, having been raised in Garrard County, KY, which lies along the edge of the Cumberland Plateau. His parents, William and Elizabeth Kincaid, were both singers. They sang in a local church, but, unlike some church-goers, they also sang some of the old love songs and ballads that Cecil Sharp had been seeking. A couple of Bradley's ballads, Fair Ellender and The Two Sisters, which he later recorded, apparently came from his mother. On one occasion Bradley said that "the hairs on the back of [his] neck would stand on end" when his mother sang "some of the old blood curdlers"! As a young man, Bradley would travel through the mountains on the lookout for new songs. He wrote the words down in old school books and in this way soon built up a repertoire of over eighty songs. In 1917 Bradley began attending Berea College. He spent two years in the army, one year in France, before graduating in 1921, when he was then twenty-six. Although Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles visited a couple of Kentucky mountain schools in 1917 (Hindman and Pine Mountain) they did not visit Berea. Having married his former music teacher, Bradley moved to Chicago, where he began singing on the radio. He was an instant success and apparently received no fewer than a third of a million fan letters within five years. Bradley Kincaid began making records in 1927.

Between December, 1927 and November, 1934, he recorded over a hundred issued sides, one hundred and four of which have been re-issued on the 4 CD set Bradley Kincaid - A Man and His Guitar (JSP Records JSP77158). He also began to issue song folios, such as Favorite (sic) Mountain Ballads and Old Time Songs which ran through six large printings within sixteen months. The edition illustrated here was printed in 1937.

Between December, 1927 and November, 1934, he recorded over a hundred issued sides, one hundred and four of which have been re-issued on the 4 CD set Bradley Kincaid - A Man and His Guitar (JSP Records JSP77158). He also began to issue song folios, such as Favorite (sic) Mountain Ballads and Old Time Songs which ran through six large printings within sixteen months. The edition illustrated here was printed in 1937.

Until the JSP set appeared in 2012, little of Bradley Kincaid's material had been reissued on CD. One track, Dog and Gun, did, however, make its way onto the Revenant double CD Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music, volume 4 (RVN211). It may be that Bradley Kincaid's voice, a soft tenor, reminiscent at times of that other Kentucky singer Buell Kazee, had by this time gone out of fashion. And that is a pity, because Bradley was an important singer, one whose singing must have encouraged many others to try their hand at music making. And, he did leave us with a fascinating collection of recordings. Dog and Gun, for example is a version of the British broadside The Squire of Tamworth (Roud 141). Timothy Connor, a prisoner of war in England during the American Revolutionary War, included the song in a song-book he compiled during his imprisonment from 1777 to 1779. Since Connor's day the song has been printed by many broadside printers, and has been widely collected in both England and America. It is a deservedly popular song with a fine romantic story. Robert Bell in Songs of the Peasantry (1857) writes that 'it is traditionally reported to be founded on an incident which occurred in the reign of Elizabeth', although this might be a rather fanciful statement. 16

16

Other British songs recorded by Bradley Kincaid are Froggie Went a-Courtin', The Swapping Song, The Foggy Dew, A Paper of Pins, I Wonder When I Shall be Married, Billy Boy and I Gave My Love a Cherry. He also recorded versions of four Child ballads, The House Carpenter, Barbara Allen, The Two Sisters (Child 10, Roud 8) and Fair Ellen (Child 73, Roud 4) and I am enclosing the latter two texts here.

The Two Sisters

There was an old woman lived on the sea-shore, bow down

There was an old woman lived on the sea-shore, bow and balance to me

There was an old woman lived on the sea-shore

And she had daughters three or four

I'll be true to my love, if my love be true to me

There was a young man came courting there

And choice he picked the youngest fair

He bought the youngest a fine fur hat

The oldest sister didn't like that

Oh sister, oh sister let's go to sea-shore

And see the ships come sailing o'er

As these two sisters walked 'long the sea-brim

The oldest pushed the youngest in

Oh sister, oh sister pray lend me your hand

And you shall have my house and land

I'll neither lend you my hand nor my glove

For all I want is your true-love

The miller got his fishing hook

And fished the fair maiden out of the brook

Oh miller, oh miller here's five gold rings

To push the fair maiden in again

The miller's to be hung on his own mill-gate

For the drowning of poor sister Kate

Fair Ellen

Oh father and mother come tell me this riddle

Come tell it all to me

The Brown Girl she has houses and land

Fair Ellen she has none

Then my advice to you, dear son

Is to bring the Brown Girl home

He dressed himself in clothes so fine

Put on a mantel in green

And every village that he rode through

He was taken to be some king

He rode till he got to Fair Ellen's hall

He jingled at the ring

And none was so ready as Fair Ellen herself

She arose and let him in

Good news, good news, fair Ellen he said

Good news I've brought to you

I've come to ask you to my wedding

For married I must be

Bad news, bad news, Lord Thomas she said

Bad news you've brought to me

You've come to invite me to your wedding

For married you must be

She dressed herself in clothes so fine

Put on a diamond ring

And every village that she rode through

She was taken to be some queen

And every village that she rode through

She was taken to be some queen

She rode till she got to Lord Thomas's hall

She jingled at the ring

And none was so ready as Lord Thomas himself

He arose and let her in

Lord Thomas, Lord Thomas, is this your bride?

She's very dark and dim

When you could have married this fair fine lady

As ever the sun shone on

The brown girl had a little penknife

It was both keen and sharp

Betwix the long rib and the short

She pierced fair Ellen's heart

Lord Thomas, Lord Thomas are you blind

And can't you very well see?

And can you see my own heart's blood

Come trink-eling down my knee?

He took the Brown Girl by the hand

And led her through the hall.

And with a sword cut off her head

And kicked it against the wall

He threw the sword upon the floor

It flew into his breast

Here lies two lovers all in a row

Lord, send their souls to rest

So dig my grave under yonder green tree

Go dig it both wide and deep

And bury Fair Ellen in my arms

And the Brown Girl at my feet

And bury Fair Ellen in my arms

And the Brown Girl at my feet

Bradley Kincaid also recorded American folksongs, such as Sourwood Mountain, Cindy, Pretty Little Pink, Old Joe Clark, Pearl Bryan, The Little Mohee, The Red River Valley, The Blue Tail Fly, a few cowboy songs, including When the Work's All Done This Fall, In the Streets of Laredo and Bury Me on the Prairie, and quite a number of late 19th century - early 20th century parlour ballads.

One song that particularly interests me is Bradley Kincaid's version of Pretty Little Pink (Roud 735):

Pretty Little Pink

Lord, Lord, my pretty little pink

Lord, Lord, I say

Lord, Lord, my pretty little pink

I'm going away to stay

Cheeks as red as the red, red rose

Her eyes like diamonds brown

I'm going to see my pretty little miss

Before the sun goes down

Fly around my pretty little miss

Fly around my daisy

Fly around my pretty little miss

You almost drive me crazy

Well, I reckon you think, my pretty little miss

That I can't live without you

But I'll let you know before I go

I care very little about you

Its rings upon my true-love's hands

Shines so bright like gold

I'm going to see my pretty little miss

Before it rains or snows

Fly around my pretty little miss

Fly around my daisy

Fly around my pretty little miss

You almost drive me crazy

When I was up in the field at work

I sat down and cried

Studying about my blue-eyed gal

I thought my soul had died

Fly around my pretty little miss

Fly around my dandy

Fly around my pretty little miss

I don't want none of your candy

Well, every time I go that road

It looks so dark and cloudy

Every time I see that gal

I always tell her, Howdy

Coffee grows on a white oak tree

The river flows with brandy

The rocks on the hills all covered with gold

And the girls all sweeter than candy

Fly around my pretty little miss

Fly around my dandy

Fly around my pretty little miss

You can't have none of my candy

Going to put my knapsack on my back

My rifle on my shoulder

I'll march away to Spartanburg

And there I'll be a soldier

Fly around my pretty little miss

Fly around my dandy

Fly around my pretty little miss

I don't want none of your candy

Well, every time I go that road

It looks so dark and hazy

Every time I see that gal

She almost drives me crazy

Fly around my pretty little miss

Fly around my dandy

Fly around my pretty little miss

I don't want none of your candy

I asked that girl to marry me

And what did she say

She said that she would marry me

Before the break of day

Fly around my pretty little miss

Fly around my dandy

Fly around my pretty little miss

You can't have none of my candy

This is a song which has turned up all over the Appalachians. I think that the first version I heard was on a 1960 recording by Clint Howard, Doc Watson and Fred Price. 17 Sometimes the song's tune is used for another common Appalachian song, Shady Grove,

17 Sometimes the song's tune is used for another common Appalachian song, Shady Grove, 18 but what fascinates me is the fact that the song is comprised of so-called floating verses. It seems to be a characteristic of many Appalachian songs that they are composed of verses which can be used in numerous songs. For example, the North Carolina singer Dellie Norton began her version of the song Black is the Colour (Roud 3103) with a verse from Pretty Little Pink.

18 but what fascinates me is the fact that the song is comprised of so-called floating verses. It seems to be a characteristic of many Appalachian songs that they are composed of verses which can be used in numerous songs. For example, the North Carolina singer Dellie Norton began her version of the song Black is the Colour (Roud 3103) with a verse from Pretty Little Pink.

Black is the Colour

My pretty little pink, so fare you well.

You've slighted me, but I wish you well.

If never on earth I no more see,

I cain't slight you like you've slighted me.

The winter have broke and the leaves are green.

The time has passed that we have seen.

But I hope the time will shortly come,

Never you and I will be as one.

Black is the colour of my truelove's hair.

Her home is on some island fair.

The prettiest face and the neatest hands.

I love the ground whereon she stands.

Off to Clyde for a weep and mourn.

Dissatisfied, I never can sleep.

I'll write to you in a few short lines.

I'd suffer death, ten thousand times.

Dellie also sang a version of the song Little Betty Ann (Roud 5720) which, again, opens with a verse that is found in Pretty Little Pink. The rest of the song comprises floating verses, as does the version sung by Dellie's one-time neighbour Inez Chandler. I am including the texts to both versions for comparison.

|

Little Betty Ann (Dellie Norton)

It's fly around my pretty little miss,

Fly around I say.

Fly around my little Betty Ann,

Girl I'm a-going away.

You slighted me all last Saturday night

And all the night before.

If I live 'til next Saturday night

You'll slight me no more.

Sixteen hundred miles away from home,

The chickens are crowing for day.

Me in the bed with another man's wife,

I'd better be a-getting away.

There's an old train a-coming, love,

She's a-giving the station blow.

Said, 'Give me a hand, my little Betty Ann,

Girl I'm bound to go.'

You slighted me all last Saturday night

And all the night before.

If I live 'til next Saturday night

You'll slight me no more.

| |

Little Betty Ann (Inez Chandler)

Till I went down to my little Betty Ann's

And I hadn't been there before.

She fed me out of the little pig trough

And I'll go there no more.

Reel and rock my little Betty Ann,

Reel and rock I say.

Reel and rock my little Betty Ann,

For love I'm going away.

Sixteen years a cannonball,

It's I've been around this line.

Sweethearts is plenty, little love,

But a good wife's hard to find.

Went up on the mountain top,

I give my horn a blow.

Yonder come my pretty little girl,

Yonder come my beau.

The hardest work I ever done

Was working in the rain.

Easiest thing I ever done

Was loving Liza Jane.

|

If we return to the song Black is the Colour we may note that some of Dellie's verses can be traced directly to British songs such as The Week Before Easter and The Rambling Boy, which contains verses such as:

The rose is red, the stem is green

The time is past that I have seen

It may be more, it may be few

But I hope to spend them all with you.

Or

Oh my pretty little miss sixteen years old

Her hair just as yeller as the shining gold

The prettiest face and the sweetest hands

Bless the ground on where she stands.

And the same may be said for other Appalachian songs, such as Pretty Saro (Roud 417), a song which, on the surface, appears to be quintessentially Appalachian. 19

19

Pretty Saro

When first to this country a stranger I came

I placed my affection on a handsome young dame

I looked all around me, and I was alone

And a poor stranger and a long way from home

Oh Saro, pretty Saro, I love you, I do

I love you, pretty Saro, wherever I go

No tongue can express it, no poet can tell

How truly I love you, oh I love you so well

Down in some lonely valley, in some lonesome place

Where the small birds are singing and the notes to increase

The thoughts of pretty Saro, so neat and complete

I want no better pastime than to be with my sweet

Oh I wish I was a poet and could write some fine hand

I would write my love a letter that she might understand

And send it by the waters where the island overflows

And think of pretty Saro wherever I go

My love she don't love me, as I understand

She wants some freeholder, and I have no land

But I can maintain her with the silver and gold

And all the pretty fine things that my love's house can hold

Oh Saro, pretty Saro, I must let you know

How truly I love you - I never can, though

No tongue can express it, no poet can tell

How truly I love you, I love you so well

It's not the long journey I'm dreading to go

Nor leaving of this country for the debts that I owe

There is but one thing that troubles my mind

That's a-leaving pretty Saro, my true love, behind

Farewell my dear father, likewise my mother too

I'm a-going to ramble this country all through

And when I get tired, I'll sit down and weep

And think of pretty Saro wherever she be

Oh I wish I was a little dove, had wings and could fly

Straight to my love's bosom this night I'd draw nigh

And in her little small arms all night I would lay

And think of pretty Saro till the dawning of day

I love you, pretty Saro, I love you, I know

I love you, pretty Saro, wherever I go

On the banks of the ocean and the mountain's sad brow

I love you then dearly, and I love you still now

But compare the words to this Irish broadside text for the song The Maid of Bunclody (Roud 3000).

The Maid of Bunclody

Oh, were I at the Moss House where the birds do increase,

At the foot of Mount Leinster or some silent place,

By the streams of Bunclody where all pleasures do meet,

And all I would ask is one kiss from you sweet.

If I was in Bunclody I would think myself at home,

'Tis there I would have a sweetheart, but here I have none.

Drinking strong liquor in the height of my cheer,

Here's a health to Bunclody and the lass I love dear.

The cuckoo is a pretty bird, it sings as it flies,

It brings us good tidings and tells us no lies.

It sucks the young bird's eggs to make its voice clear,

And the more it cries cuckoo, the summer draws near.

If I was a clerk and could write a good hand,

I would write my love a letter that she might understand,

For I am a young fellow that is wounded in love,

Once I lived in Bunclody but now must remove.

If I was a lark and had wings I could fly,

I would go to yon arbour where my love she does lie,

I'd proceed to you arbour where my true love does lie,

And on her fond bosom contented I would die.

'Tis why my love slights me as you may understand,

That she has a freehold and I have no land,

She has great store of riches and a large sum of gold,

And everything fitting a house to uphold.

So adieu my dear father, adieu my dear mother,

Farewell to my sister, farewell to my brother;

I am bound for America, my fortune to try,

When I think of Bunclody, I'm ready to die.

Verse 3 of The Maid of Bundclody also turns up in the song The Cuckoo (Roud 413), which, in America, is often changed to read:

The cuckoo she's a pretty bird

She warbles as she flies

She never sings cuckoo

Till the fourth of July

Many English singers remember this verse, while forgetting the rest of the song, although at least one singer keeps his family version of the song alive today. This is Bob Lewis of Sussex and it is interesting to see how verses 2 and 3 of his version can be found in the American song On Top of Old Smokey. 20

20

The Cuckoo

The cuckoo is a fine bird

She sings as she flies

She brings us good tidings

And she tells us no lies

She sups the sweet flowers

For to make her voice clear

And the more she cries, cuckoo

The summer draws near

It was walking and a-talking

And a-walking was I

For to meet my own truelove

He's a-coming by and by

For to meet it's a pleasure

And to part it's a grief

And a false-hearted truelove

Is worse than a thief

For a thief he will rob you

Of all that you have

But a false-hearted truelove

Will bring you to the grave

The grave it will rot you

And bring you to dust

So false-hearted young men

I'll never more trust

Once I had the colour

Like a bud of a rose

But now I'm as pale as

The lily that grows

Like a flower in the morning

Cut down in full bloom

What do you think I'm a-coming to

By the loving of one?

Come all pretty maidens

In every degree

Don't trust in young sailors

In any degree

They'll kiss you and court you

And swear to be true

And the very next moment

They'll bid you adieu

They'll laugh and they'll drink

As they see you pass by

They'll bow down before you

With a wink of an eye

They'll kiss and they'll court you

For girls to deceive

There is not one in twenty

That a maid can believe

Before I leave the subject of so-called floating verses, verses which pass freely between any number of songs, I should add that in 1985 Flemming G Anderson produced a study of lines, verses or sequences of verses (he called them 'commonplace or floaters') which occur in various Child ballads, and his book Commonplace and Creativity. The Role of Formulaic Diction in Anglo-Scottish Traditional Balladry (Odense: Odense University Press. 1985) should be read by anybody with the slightest interest in the subject. There are several examples of these commonplaces in the ballad Fair Ellen, given above. This verse, for example, turns up in several other ballads.

She dressed herself in clothes so fine

Put on a diamond ring

And every village that she rode through

She was taken to be some queen

These sort of things remind me of the epic Balkan ballad singers who memorized hundreds of stock lines and phrases, so that when, say, they needed to describe a person moving from one place to another, they already had a ready-made verse, similar to the above, which they could drop into the narrative. 21

21

In both parts of When Cecil Left the Mountains I have concentrated on some of the songs and ballads which were recorded commercially in the 1920's and '30's. But the record companies also recorded instrumental, often fiddle-led, music. During the period 1921 - 1942 at least twenty groups recorded versions of the tune Soldier's Joy, while some seventeen groups recorded versions of The Girl I Left behind Me. Other instrumental groups recorded tunes such as Speed the Plough, Money Musk, Miss McLeod's Reel, Paddy on the Turnpike, Polly Put the Kettle On and other old-world tunes. These tunes can be traced to England, Ireland and Scotland, while other tunes, Fire in the Mountains for example, can be traced to Eastern Europe.

There are various ways of judging just how popular old-world tunes were in America. One way would be to analyse American printed tune-books. Another way, and I think that this is a better way, is to consider the repertoire of just one mountain fiddler, namely the blind fiddler Ed Haley (1883 - 1951). Ed was born in Logan County, WVA, and played around the eastern Kentucky-western West Virginia region for most of his life. During the period 1946 - 1947 Ed's son, Ralph Haley, recorded his father on a home disc-cutting machine. In 1997 Rounder Records issued sixty-five of these recordings on two double CD sets - Ed Haley: Forked Deer, CD1132 - 33, and Ed Haley: Grey Eagle, CD1134 - 35 - and I would estimate that over a quarter of these tunes (30% actually) can be traced back to old-world sources. 22 These are:

22 These are:

|

CD1

|

|

Forked Deer | Known in America as early as 1839, the 'fine' strain of Forked Deer is similar to an old Scotch-Irish tune called Rachael Rae, which is believed to have been composed in 1815 by a Scottish composer called Joseph Lowe. O'Neill called it The Moving Bogs.

|

|

Indian Ate the Woodchuck | The second strain of this superb tune is clearly related to the tune Such a Getting Upstairs, which is also known as The Fife Hunt.

|

|

Humphrey's Jig | A version of Bob of Fettercairn which can be found in the 18th century Scots Musical Museum.

|

|

Love Somebody | A version of My Love She's But a Lassie Yet printed in 1757 as Miss Farquharson's Reel in Bremner's Scots Reels.

|

|

Salt River | Seems to be related to the Irish tune Carron's Reel, which, according to Francis O'Neill, became attached to the Scots poem The Ewe wi the Crooked Horn.

|

|

CD2

|

|

Jenny Lind Polka | Composed by a German composer Anton Wallerstein c.1850.

|

|

Chicken Reel | Not the usual tune by this name, but possibly one based on an older, and untraced, Scots melody.

|

|

Wake Up Susan | Known in Ireland as The Mason's Apron.

|

|

CD3

|

|

Grey Eagle | Tune 1214 in O' Neil's "Music of Ireland", where it is titled The First Month of Summer. In Scotland it is known as The Miller of Drone.

|

|

Wilson's Jig | Known under various old-world titles, including Harvest Home, Dundee Hornpipe, Cliff Hornpipe, Ruby Lip, Kildare Fancy and Cork Hornpipe.

|

|

Bonaparte's Retreat | Possibly based on an old British tune.

|

|

Money Musk | Believed originally titled Sir Archibald Grant of Monie Muske's Reel and possibly composed by Daniel Gow in 1776. Apparently once used in Ireland to accompany the Highland Fling.

|

|

CD 4

|

|

Cumberland Gap | A tune which resembles Skye Air (Gow # 559).

|

|

Parkersburg Landing | A Variation of the well-known Schottische The Rustic Dance. Also similar to Mrs Kenny's Barndance as recorded by Michael Coleman.

|

|

Cuckoo's Nest (1) | Similar to All Aboard Reel in Ryan's Mammoth Collection.

|

|

Cuckoo's Nest (2) | Known in Ireland under a number of different titles, including Peacock Feathers, Forty Pounds of Feathers, In a Hornet's Nest, Jacky Tar or Jolly Jar Tar With Your Trousers On.

|

|

Paddy on the Turnpike | Based on The Bell of Claremont Hornpipe, with a second strain which sounds like Johnny Cope and which is probably based on a tune for The Gaberlunzie Man.

|

|

Fire in the Mountains | Known in Eastern Europe under a number of titles. It also turned up in Riley's Flute Melodies of 1815, as Free on the Mountains (Vol.1, p.87,# 317).

|

|

Pumpkin Ridge | Also called Marmaduke's Hornpipe. According to some sources, Irish fiddler Michael Coleman recorded a version of the tune, although I am unable to trace this recording.

|

|

Mississippi Sawyer | Possibly based on an old-world tune, The Downfall of Paris.

|

In August, 1979, I drove up a steep hillside above Boones Mill in Franklin County, VA, to meet fiddle-player Sherman Wimmer. One tune that Sherman liked to play was titled Twin Sisters and was a version of a hornpipe that I knew as The Boys of Bluehill. I had first picked the tune up from a recording of Irish musicians and was delighted to hear Sherman's version. I had always assumed that it was an Irish tune (Ryan's Mammoth Collection calls it The Boys of Oak Hill), although there are some 19th century Scottish printings of the tune. The earliest (?) American version, titled The Two Sisters, can be found in Knauff's Virginia Reels of 1839. A few days after meeting and hearing Sherman Wimmer I met up with another fiddler, Taylor Kimble of Laurel Forks in Carroll County, VA. Taylor was quite ill when I met him, although he insisted on playing me a few tunes, one being his version of The Boys of Bluehill, which he called The Old Ark's a-Moving. And there were other titles for the piece, The Jimmy Johnson String Band, from Kentucky, called it Jenny Baker, while other performers called it Pussy and the Baby, Hell on the Wabash or Beau of Oak Hill. Kentucky fiddler William B Houchens included the tune in a 1922 medley of tunes titled Turkey in the Straw.

In fact, so many versions of this tune have turned up across America that some authorities have begun to wonder whether or not it is really an Irish tune, or, is it, perhaps, actually an American tune; one which, somehow or other, later found its way to Ireland. And perhaps this is not such a wild idea; after all, today we are inundated with American music in Britain and I suppose that I should not have been surprised a few days ago when I heard the American fiddle tune Listen to the Mockingbird being used to back an English TV advertisement. Once, when America really was the New World, music only flowed one way; namely from Europe to America (and from Africa to America when slaves were being transported across the Atlantic) whereas, today, it is a river that flows in both directions. Now, with music moving both ways, I suppose that we can say that the circle has been completed.

I wonder what Cecil Sharp would have made of it, though?

Mike Yates - 27.12.14

Wiltshire

Footnotes:

1. You can hear Will Starks's 1942 recording of The Fox Hunter's Song on the CD Deep River of Song - Mississippi: Saints and Sinners Rounder CD 1824.

2. The Gallis Pole is included on the 4 CD set Leadbelly - Important Recordings 1934 - 1949 JSP box set 7764.

3. Seven Curses can be heard on the CD set Bob Dylan - the bootleg series volumes 1 - 3 (rare & unreleased) 1961 - 1991 Columbia 488100 2. It may be that Dylan also used the song Anathea, as sung by Judy Collins, as the basis for Seven Curses.

4. Jack Hall, as sung by Walter Pardon, can be heard on volume 17 of Topic Record's Voice of the People series - TSCD 667. Sadly, Gordon Hall's version does not appear to be currently available.

5. Emry Arthur's original recording of Ethan Lang can be heard on Vocalion Vo5249. It has been re-issued on the 4 CD set Appalachian Stomp Down JSP 7761

6. In Part One of this article (Musical Traditions article # 255) I mistakenly said that it was Bella Lam, and not Emry Arthur, who recorded the song Wandering Gypsy Girl in 1928.

7. The Soldier and the Lady, sung by Fred and Ray Cantwell, can be heard on Rounder CD Songs of Seduction, CD 1778. The Irish Soldier and the English Lady, sung by Neil Morris, can be heard on the Round CD Southern Journey - Ozark Frontier, Rounder CD 1707. There is another fine, if short, version sung by Mildred Tucker of KY on the double CD Meeting's a Pleasure, volume 1. MTCD341-2.

8. Booklet notes to the CD Roger Cooper: Going Back to Old Kentucky, Rounder CD0380.

9. The Banks of Claudy, sung by Bob & Jim Copper. Topic CD TSCD534.

10. Where Are You Going Alice? , sung by Grayson & Whitter. Re-issued on the 4 CD set Appalachian Stomp Down JSP 7761.

11. Going Down the Lee Highway, sung by Grayson & Whitter. Re-issued on the 4 CD set Appalachian Stomp Down JSP 7761. It seems almost certain that the tune was composed by Grayson.

12. Johnny Goodwin, played and sung by the Bull Mountain Moonshiners. Re-issued on the 4 CD set The Bristol Sessions JSP 77156.

13. Jimmie and Sallie, sung by The Dixon Brothers. Re-issued on Document CD Dixon Brothers Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order Volume 4 - 1938. DOCD-8049.

14. The Story of George Collins sung by The Dixon Brothers. Re-issued on Document CD Dixon Brothers Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order Volume 4 - 1938. DOCD-8049.

15. George Collins sung by Roy Harvey. Available on various CD re-issues.

16. For English versions of Dog and Gun, one sung by Frank Hinchliffe of Yorkshire and another by George Fradley of Derbyshire, see Musical Tradition's double CD Up in the North and Down in the South MTCD311-2 and Veteran's CD It Was on a Market Day - volume 2 VTC7CD.

17. Pretty Little Pink is performed by Clint Howard, Doc Watson and Fred Price on the double Smithsonian-Folkways set Doc Watson and Clarence Ashley. The Original Folkways Recordings, 1960 - 1962. CD SF40029/30. Fred Price also provides a splendid version of Going Down the Lee Highway, which he learnt from G B Grayson, a close friend.

18. Clarence Ashley sings a good version of Shady Grove on the double Smithsonian-Folkways set Doc Watson and Clarence Ashley. The Original Folkways Recordings, 1960 -1962. CD SF40029/30. Doc Watson also has a good version on The Watson Family, Smithsonian-Folkways CD SF40012.

19. Dolly Greer sings a fine version of Pretty Saro on The Watson Family, Smithsonian-Folkways CD SF40012, and Cas Wallin sings an equally fine version on Dark Holler. Old Love Songs and Ballads Smithsonian-Folkways SFW CD 40159.

20. Bob Lewis can be heard singing The Cuckoo on the Veteran CD Stepping It Out VTC1CD. There is another good, American, version on Doc Watson and Clarence Ashley. The Original Folkways Recordings, 1960 - 1962. CD SF40029/30.

21. See Albert Bates Lord, The Singer of Tales. London, Macmillan, 1965, for more on this subject.

22. I have also made a check of the 50 tunes which the West Virginian fiddler Edden Hammons (c.1874 - 1955) recorded in 1947. I would estimate that at least 23% of these tunes can be traced to British and Irish sources. See The Eddens Hammond Collection, volume 1 & The Eddens Hammond Collection, volume 2, West Virginia University press, 2 CDs, SA-1 and SA-2.

Appendix - Fifty Essential CDs of Appalachian Music.

(This is, of course, a personal list. Others may disagree!)

A. Solo/single group performers.

-

1. Jean Ritchie, Ballads from her Appalachian Family Tradition. Smithsonian-Folkways SFW CD 40145.

-

Sixteen Child ballads sung by one of the greatest Appalachian singers. Cecil Sharp would have loved this!

-

2. Frank Proffitt of Reese, NC, Folk-Legacy CD-1.

-

A wonderful performer who had a large repertoire of rare and unusual songs and ballads.

-

3. The Watson Family, Smithsonian-Folkways CD SF40012.

-

First recordings of Doc Watson and his family.

-

4 - 5. Doc Watson and Clarence Ashley. The Original Folkways Recordings, 1960 - 1962. CD SF40029/30.

-

Lovely collection of songs and instrumentals.

-

6. Bascom Lamar Lunsford, Ballads, Banjo Tunes, and Sacred Songs of Western North Carolina. Smithsonian-Folkways SF CD 40082.

-

Lunsford was an important collector/singer who preserved many songs and ballads which would otherwise have disappeared.

-

7. Texas Gladden, Ballad Legacy, Rounder CD 1800.

-

Another splendid ballad singer.

-

8 - 9. Hobart Smith, Blue Ridge Legacy, Rounder CD 1799 & In Sacred Trust. The 1963 Fleming Brown Tapes. Smithsonian-Folkways SFW C 40141.

-

Brother of Texas Gladden, this multi-instrumentalist and singer just about sums up all that is good in Appalachian music.

-

10 - 11. Roscoe Holcomb. The High Lonesome Sound, Smithsonian-Folkways SF CD 40104 & An Untamed Sense of Control, Smithsonian-Folkways SFW CD 40144.

-

Banjo-player and singer, Roscoe Holcomb first appeared on the double CD set Mountain Music of Kentucky, compiled and annotated by John Cohen (#'s 43 - 44 below). These two solo albums confirm his status as one of the most outstanding Appalachian performers ever recorded.

-

12 - 13. The Hammons Family. The Traditions of a West Virginia Family and their Friends. Rounder 1504/05.

-

A successful attempt by Carl Fleischhauer and Alan Jabbour of the Library of Congress to present a fuller, more rounded, picture of the musical culture of one Appalachian family.

-

14 - 16. Dock Boggs. Country Blues, Complete Early Recordings (1927 - 29), Revenant 205. Dock Boggs, his Folkways Years, Smithsonian-Folkways SF 40108.

-

Three CDs worth of material from the legendary banjo-player/singer who cut twelve sides in 1927 - 29 before vanishing into obscurity. He was rediscovered some thirty years later, when he was recorded extensively.

-

17 - 18. Ernest V Stoneman, The Unsung Father of Country Music, 1925 - 1934. 5- String Productions 5SPH 001.

- Stoneman, along with his family and friends from the area around Galax, VA, recorded dozens of songs and tunes. This 2 CD selection contains some of the best.

-

19. I'm Going Down to North Carolina. The Complete Recordings of the Red Fox Chasers, 1928 - 31.Tompkins Square TSQ 2219.

-

Excellent collection of songs and string band music from one specific region of north- west North Carolina.

-

20. Da Costa Waltz's Southern Broadcasters & Frank Jenkins' Pilot Mountaineers, Document DOCD-8023.

-

Early string bands from the area around Galax, NC. (See also # 29 below).

-

21 - 24. Charlie Poole with the North Carolina Ramblers and the Highlanders, JSP 4 CD box set, JSP7734.

-

Poole's music ranged from ancient ballads to more modern pieces, and showed how the music was rapidly changing.

-

25 - 28. The Carter Family, 1927 - 1934. JSP 4 CD box set, JSPCD7001.

-

From the hills of Virginia. No matter what they played, they were always rooted in their native soil. One of the most influential groups ever to be recorded. Their 1935 - 1941 recordings are also available on another 4 CD box set, JSP7708.

-

29. Old Time Mountain Music, with Oscar Jenkins, Fred Cockerham & Tommy Jarrell, County CD 2735.

-

Three friends who kept their regional music alive. Jarrell was the son of fiddler Ben Jarrell, who recorded with Da Costa Waltz's Southern Broadcasters in 1927. (See # 20 above).

B. Anthologies:

-

30. Dark Holler. Old Love Songs and Ballads Smithsonian-Folkways SFW CD 40159.

-

Field recordings of singers who learnt their songs from people who sang to Cecil Sharp in 1916. Also come with a DVD, The End of An Old Song, John Cohen's portrait of Appalachian singer Dillard Chandler.

-

31. High Atmosphere. Ballads and banjo tunes from Virginia & North Carolina. Rounder CD 0028.

-

Excellent set of field recordings made by John Cohen in 1965.

-

32 - 38. Kentucky Mountain Music. Classic Recordings of the 1920s & 1930s.

-

Rare and essential commercial recordings of Kentucky mountain music, together with Alan Lomax's 1937 Kentucky Library of Congress recordings.

-

39. Southern Journey. Volume 2. Ballads and Breakdowns, Songs from the Southern Mountains. Rounder CD 1702.

Good selection of songs, ballads and instrumental tunes. Other recordings by some of these artists can be found scattered throughout the other 12 CDs in this series.

-

40. Music from the Lost Provinces. Old-Time stringbands from Ashe County, North Carolina and Vicinity. 1927 - 1931. Old Hat CD-1001.

-

Important early recordings by such people as Grayson & Whitter, Frank Blevins, Jack Reedy and The Hill Billies.

-

41 - 42. Mountain Music of Kentucky, compiled and annotated by John Cohen. Smithsonian-Folkways SF CD 40077.

-

Great selection of recordings made in 1959.

-

43 - 44. The Traditional Music of Beech Mountain. Volume 1, The Older ballads and Gospel Songs, Folk-Legacy CD-22. The Traditional Music of Beech Mountain. Volume 2, The Later Songs and Hymns, Folk-Legacy CD-23.

-

Two of the best albums ever made of traditional Appalachian singers and their ballads and songs.

-

45 - 48. Meeting's a Pleasure. Folk-Songs from the Upper South, Volumes 1 & 2, and Volumes 3 & 4. Two double CDs. Musical Traditions MTCD505-6 & MTCD507-8.

-

Over 130 tracks of material collected in Kentucky & West Virginia, showing a very strong tradition.

-

49 - 50. The North Carolina Banjo Collection, Rounder CD 0439/40.

-

The banjo entered the Appalachians via Afro/American slaves. These two CDs show just how much one instrument could influence the various directions that traditional music could take.

Article MT297

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 27.12.14

Actually, although the British claim this song, usually under the title Brighton Camp which can be traced to the 1750s, the Irish believe it to be an Irish piece, An Spailpin Farnach (The Rambling Labourer), which can also be dated to the 18th century.

Actually, although the British claim this song, usually under the title Brighton Camp which can be traced to the 1750s, the Irish believe it to be an Irish piece, An Spailpin Farnach (The Rambling Labourer), which can also be dated to the 18th century.

Between December, 1927 and November, 1934, he recorded over a hundred issued sides, one hundred and four of which have been re-issued on the 4 CD set Bradley Kincaid - A Man and His Guitar (JSP Records JSP77158). He also began to issue song folios, such as Favorite (sic) Mountain Ballads and Old Time Songs which ran through six large printings within sixteen months. The edition illustrated here was printed in 1937.

Between December, 1927 and November, 1934, he recorded over a hundred issued sides, one hundred and four of which have been re-issued on the 4 CD set Bradley Kincaid - A Man and His Guitar (JSP Records JSP77158). He also began to issue song folios, such as Favorite (sic) Mountain Ballads and Old Time Songs which ran through six large printings within sixteen months. The edition illustrated here was printed in 1937.