with descriptions of some of the celebrations of old, garnered by Alan Helsdon

In 1864 Chappell & Co of London published the sheet music for 'An Ancient English Melody, Arranged and Dedicated to the Landowners and Farmers of Norfolk, by Mrs Haggard.' It was the harvest supper celebration song from her farm at West Bradenham in central Norfolk. It sold for 2/6 (12.5p) and is remarkable in three ways:

Firstly it is early. The Percy Society was founded in 1840. It included William Chappell and produced publications from then. William Chappell himself published A Collection of National English Airs, in 2 volumes, in 1838 & 1840, and revised and extended this into The Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Times, 17 parts from 1855 to 1859. John Broadwood produced Old English Songs in 1847. James Orchard Halliwell published Norfolk Anthology in 1852. (Information from Steve Roud, Folk song in England, 72 - 76)

Secondly it was noted by a woman. 'Marianne Mason (1845 - 1932) was the first woman to publish a collection of folk songs.' This was Nursery Rhymes and Country Songs, which appeared in 1878, 14 years after Ella Haggard's single foray in this field. Lucy Broadwood & H F Birch Reynardson brought out Sussex Songs in 1890, 26 years after the Bradenham publication. Obviously Ella Haggard's work has been nowhere near as influential, indeed it has lain unknown in Norwich Library for a very long time as far as I know, but its very isolation shows Ella Haggard's originality and determination to preserve what she saw as a valuable snippet of local life. No details exist (Chappell have no records that old) but it seems probable that Ella herself may well have paid for the publication, albeit with the possibility of the fair wind of Chappell's enthusiasm. He died in 1888; Ella in 1889. (Information from Steve Roud again.)

Thirdly it was noted in its environment and the circumstances written about in detail. The late Norris Winstone MBE, founder of Kemp's Men and much-lamented guru of all Norfolk dance tunes, insisted on using 'noted' instead of 'collected' because to note something is to record its exisitence in order to share it with others and thus keep it alive, but to collect something is to remove it from its environment, in much the same way as Victorian sportsmen celebrated the finding of a rare species of bird by shooting it, stuffing it and putting it in a cabinet at home. Ella Haggard published not only the tune and words but described in detail the rituals that went with it (see below) and for all the right reasons as we now see them.

Thankfully it contains both words and music. Most of the time taken in producing the 2 CD-ROMs Vaughan Williams in Norfolk was spent searching for word sets to fit the tunes he noted in order to turn them into songs again. To quote Steve Roud (p.42) 'Alfred Williams is the only one of the major collectors to think more of the words than the tunes.'

Ella (née Doveton) and husband William Meybohm Rider Haggard were not typical Norfolk landowners / farmers, however. She was born in Bombay and he in St Petersburgh. He was a Barrister, but according to the censuses not practising after the age of 33 and possibly regularly on the farm at West Bradenham, which is still there. They also produced 10 children, one of whom was the author Henry Rider Haggard, born 1856. He says of his mother, in his diary The Days of My Life, 1911, that 'she was a good musician.'![]() 1 Ella seemed to travel a lot and was a visitor in someone else's home on both 1871 and 1881 censuses.

1 Ella seemed to travel a lot and was a visitor in someone else's home on both 1871 and 1881 censuses.

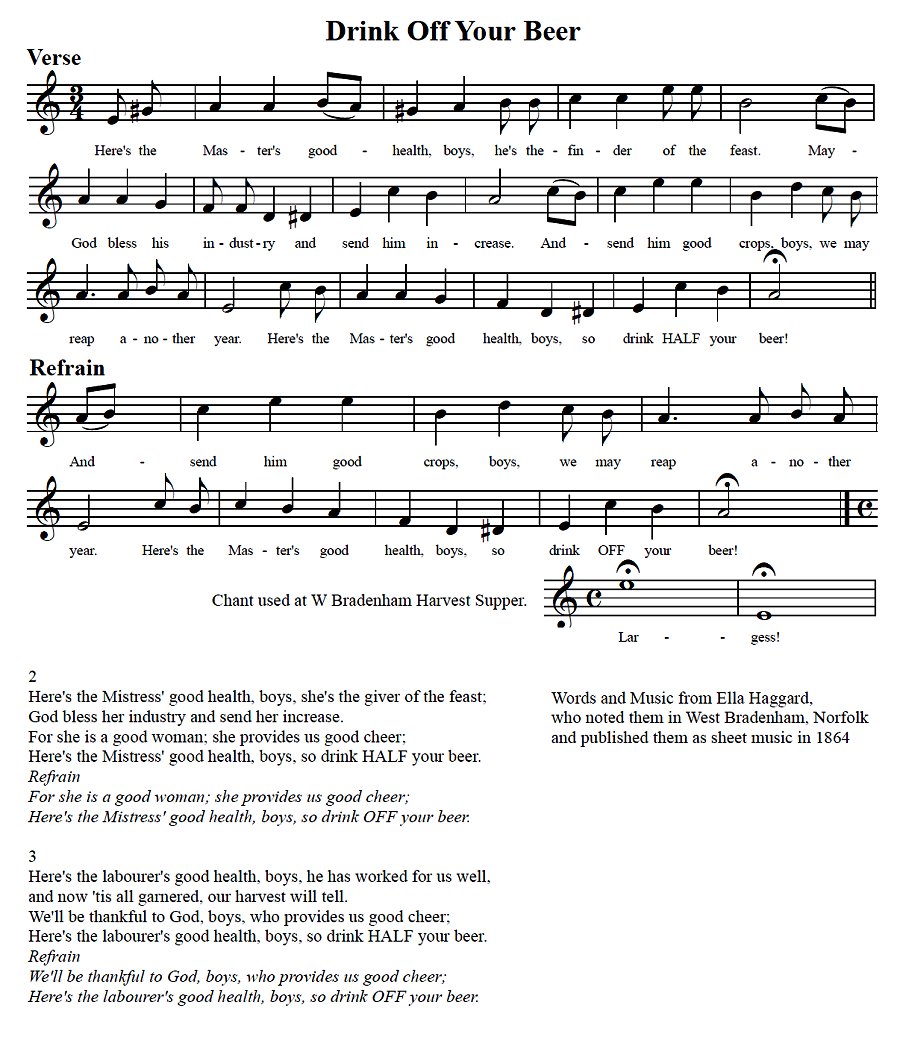

From the sheet music published in 1864 by Ella Haggard (1819 - 1889):

Supper being ended, a fresh supply of beer is called for, and a mug being filled, and presented to one of the party. All stand up, and with the exception of the drinker, begin singing the Harvest Song. The person holding the mug is not to taste the contents till desired in the second part of the tune, to drink half his beer, when he does so, and on the repetition of the [refrain] he swallows the remainder, the last note being prolonged to enable him to do so.

The mug is then passed on, and the song begins afresh, till all have drunk, when the whole is repeated to celebrate the health of the Mistress in like manner.

When the labourers are numerous, the ceremony is a very lengthy one, and it is generally terminated (if the Master's family be present) by the still more quaint and ancient custom of 'crying largess', to do which, all the party join hands and stand in a circle, the chief labourer (styled The Lord) standing alone and blowing a horn in the centre, to the sound of which they all sing the word "largess" three times, throwing their hands up in the air while the first note is sustained, and lowering them at the second. A subscription (to provide tea for the wives and children) from the Master's family, generally answers this appeal.

The characteristic air, which probably dates from the days of Queen Elizabeth, if not earlier, is sung to the words of the Harvest Song in the village of West Bradenham in Norfolk, and has been noted down to preserve it from fading into oblivion ... believing that it is the duty of all interested in the welfare of our English peasantry, to encourage and maintain, to the utmost, the surviving relics of those few and hardly-earned opportunities of domestic and social gathering, that yet linger among them, to reward and enliven their daily and incessant toil.

Persons acquainted with Norfolk and Suffolk will recognise the description of this ancient custom, as it is commonly practised in the field by the labourers and gleaners during the harvest season, to obtain a donation from the passing or intruding stranger. From the Norman word used it might be supposed to date from feudal times; but the author has been informed that similar customs prevail in Devonshire and Cornwall, the word being sung, "there", a celtic one; so that it probably has a much earlier origin.

From Vaughan Williams in Norfolk, Vol 2:

We don't know whether he learnt this song in Suffolk in his youth, got it when older from farms in Norfolk, or even sang an amalgamated version to Vaughan Williams, but songs wishing health to the Master and Mistress had many similarities in both counties and undoubtedly the 'aural tradition' was at work.

Having also been noted by Cecil Sharp in Oxfordshire, I have set it to that melody.

[The Norfolk Largess, Norfolk Harvest Song and Ploughboy's Round had no tunes and I have 'borrowed' three excellent, Norfolk-found tunes for them, noted by Ralph Vaughan Williams in King's Lynn in 1905.]

This comes from Ballads, Songs and Rhymes of East Anglia, by A S Harvey, 1936, who is quoting from History of Hawsted, 1813, by Rev. John Cullum Bart. FRS, FSA.

A S Harvey, in his 1935 Ballads, Songs and Rhymes of East Anglia includes two songs entitled Norfolk Harvest Song and Harvest Song Refrain. He introduces them by saying that these are 'from Bygone Norfolk [1898] by William Andrews. The latter is all that remains of another Norfolk Harvest Song which was a great favourite in olden times.' What I have done, as the metre is the same for both, is to use the Refrain as the chorus to the 4 verses of the Song. I've been singing it for about 40 years and nobody has ever noticed.

Lamas Day is August 1st and was about the time harvesting the cereal crops began, though I'm sure the weather, as, now, had a say in things. The 'early horn' was blown centrally in the village to get the workers to the fields on time.

From honearchive.org this a small part of the attractivly named 'Ten Minute Biography':

From Ballads, Songs and Rhymes of East Anglia, by A S Harvey, 1936, quoting from The East Anglian, Vol III, 1869, p.264:

The Duke of Norfolk lived in what is now Duke Street in Norwich and built a palace in about 1651 on the site of the present (2017) multi-storey car park. The palace was demolished from about 1751, possibly because of subsidence, but some historians have suggested it was because of a row between the Duke of Norfolk and the Mayor of Norwich. (Norwich Evening News, 31.03.2015). These colourful tales can cast a long shadow in the local consciousness!

Written on August 14th 1826 and sent in by a contributor known only as 'G. H. I.':

At the conclusion of wheat harvest, it is usual for the master to give his men each a pot or two of ale, or money, to enable them to get some at the alehouse, where a merry meeting is held amongst themselves.

The last, or 'horkey load' (as it is here called) is decorated with flags and streamers, and sometimes a sort of kern baby is placed on the top at front of the load. This is commonly called a 'ben'; why it is so called, I know not, nor have I the smallest idea of its etymon, unless a person of that name was dressed up and placed in that situation, and that, ever after, the figure had this name given to it.![]() 2 This load is attended by all the party, who had been in the field, with hallooing and shouting, and on their arrival in the farmyard they are joined by the others. The mistress with her maids are out to gladden their eyes with this welcome scene, and bestir themselves to prepare the substantial, plain, and homely feast, of roast beef and plumb pudding.

2 This load is attended by all the party, who had been in the field, with hallooing and shouting, and on their arrival in the farmyard they are joined by the others. The mistress with her maids are out to gladden their eyes with this welcome scene, and bestir themselves to prepare the substantial, plain, and homely feast, of roast beef and plumb pudding.

On this night it is still usual with some of the farmers to invite their neighbours, friends, and relations to the 'horkey supper'. Smiling faces grace the festive board; and many an ogling glance is thrown by the rural lover upon the nutbrown maid, and returned with a blushing simplicity, worth all the blushes ever made at court. Supper ended, they leave the room, (the cloth, &c. are removed,) and out of doors they go, and a halloing 'largess' commences.

The men and boys form a circle by taking hold of hands, and one of the party standing in the centre, having a gotch of horkey ale placed near him on the ground, with a horn or tin sort of trumpet in his hand, makes a signal, and "halloo! lar-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-ge-ess" is given as loud and as long as their lungs will allow, at the same time elevating their hands as high as they can, and still keeping hold. The person in the centre blows the horn one continued blast, as long as the 'halloo largess'. This is done three times, and immediately followed by three successive whoops; and then the glass, commonly a horn one, of spirit-stirring ale, freely circles. At this time the hallooing-largess is generally performed with three times three.

This done, they return to the table, where foaming nappy ale is accompanied by the lily taper tube, and weed of India growth; and now mirth and jollity abound, the horn of sparkling beverage is put merrily about, the song goes round, and the joke is cracked. The females are cheerful and joyous partakers of this "flow of soul."

When the juice of the barrel has exhilarated the spirits, with eyes beaming cheerfulness, and in true good rustic humour, the lord of the harvest accompanied by his lady, (the person is so called who goes second in the reap, each sometirres wearing a sort of disguise,) with two plates in his hand, enters the parlour where the guests are seated, and solicits a largess from each of them. The collection made, they join their party again at the table, and the lord recounting to his company the success he has met with, a fresh zest is given to hilarity, a dance is struck up, in which, though it can hardly be said to be upon the 'light fantastic toe' the stiffness of age and rheumatic pangs are forgotten, and those who have passed the grand climactric, feel in the midst of their teens.

Another show of disguising is commonly exhibited on these occasions, which creates a hearty rustic laugh, both loud and strong. One of the party habited as a female, is taken with a violent pang of the toothache, and the doctor is sent for. He soon makes his appearance, mounted on the back of one of the other men as a horse, having in his hands a common milking stool, which he bears upon, so as to enable him to keep his back in nearly a horizontal position. The doctor brings with him the tongs, which he uses for the purpose of extracting the tooth: this is a piece of tobacco pipe adapted to the occasion, and placed in the mouth; a fainting takes place from the violence of the operation, and the bellows are used as a means of causing a reviving hope.

When the ale has so far operated that some of the party are scarcely capable of keeping upon their seat, the ceremony of drinking healths takes place in a sort of glee or catch ... This health-drinking generally finishes the horkey. On the following day the party go round among the neighbouring farmers (having various coloured ribands on their hats, and steeple or sugar-loaf formed caps, decked with various coloured paper, etc,) to taste their horkey beer, and solicit largess of any one with whom they think success is likely. The money so collected is usually spent at the alehouse at night. To this 'largess money spending', the wives and sweethearts, with the female servants of their late masters, are invited ; and a tea table is set out for the women, the men finding more virtue in the decoction of Sir John Barleycorn, and a pipe of the best Virginia.

Quoting from History of Hawsted, 1813, by Rev. John Cullum Bart. FRS, FSA.:

On a Saturday morning immediately after harvest two farm hands entered the office and said to the cashier:

"Mornin marster - we ha' come to ax yer whether you'll stow a largiss on us. We wark for Mister Fillerpew o' Ossfer who buy 'is coal here."

Knowing that Mr Phillipo of Horsford was a regular customer, the cashier handed over two separate shillings and the men went straight over to the Coachmaker's Arms and were doubtless well looked after by the late Jimmy Banham (of Norfolk County Crciket fame).

Fred C Leeds, Norwich

A J Rudd, Norwich

The Horkey itself, called a 'frolluck' by my grand- parents, was paid for by the farmer and was usually held in a big barn which had been cleared to make way for trestle tables loaded with cold cooked beef, ham, cheese and pickles, apple pie and plum duff with beer to drink. The farmer made a speech thanking his workers and the Lord of the Harvest replied on their behalf. Everyone was happy and relaxed; another harvest had been safely gathered in and now they could enjoy themselves. They ate and drank, danced and sang ...

[Necton is just south of the A47 between Swaffham and Dereham, adjacent to the Bradenham Hall Farm of the Rider Haggards. Sadly, all 4 pubs are now closed - norfolkpubs.co.uk.]

Social Dancing in a Norfolk Village 1900 - 1945; Ann-Marie Hulme & Peter Clifton, Folk Music Journal, 1978, Vol 3, No 4.

I remember one old chap in particular singing: 'I've got sixpence, a jolly, jolly sixpence; I love sixpence better than my life.' He sang this song every year; I think it must have been the only one he knew.

After harvest was finished we went gleaning and would get quite a lot for the pigs and chickens. We would have aprons with large pockets in the front to put the short ears in and those with long straws would be tied into bunches.

[Shotesham All Saints is a village 6 miles South from Norwich and Shotesham St Mary (including S Martin and Botolph) is 5 miles.]

[Mulbarton is a parish and village 5 miles South-West from Norwich - Harrod's 1876 Directory of Norfolk.]

Alan Helsdon, Norwich - 1.1.18

2. See the explanation of 'Barlow' Debbage in my CD-ROM Vaughan Williams in Norfolk Vol 2 for how a name can attach itself like this.

Article MT314

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |