[Introduction] [The Background] [English Song Collectors] [Singers' Repertoires] [Minstrelsy] [Print] [Changes in Collecting Attitudes] [Conclusions] [Notes]

Two other recordings were of songs which have turned in the repertoires of other British singers, though which were not, apparently, sung by Walter Pardon. These are:

Over the years there have been very few studies of American songs that have been found in the repertoires of English 'traditional' singers, such as Walter Pardon. In order to begin to rectify this situation Musical Tradition Records issued a three CD set of recordings - Wait Till the Clouds Roll By (Musical Traditions MTCD518-0) - in early 2020. There are a total of 34 early American recordings of songs and tunes from America, as well as 42 American songs and tunes from British singers on the Wait Till the Clouds Roll By set.![]() 1 As is usual with Musical Traditions CDs, a booklet of notes accompanies each album, and a further article, also titled Wait Till the Clouds Roll By (Musical Traditions article number 328), also accompanies the series. This present article takes a more detailed look at just how, and why, American songs and tunes entered the English musical tradition.

1 As is usual with Musical Traditions CDs, a booklet of notes accompanies each album, and a further article, also titled Wait Till the Clouds Roll By (Musical Traditions article number 328), also accompanies the series. This present article takes a more detailed look at just how, and why, American songs and tunes entered the English musical tradition.

This, of course, is one of the problems with 'history' ... most of it relies on the written record, and such records relating to ordinary people will only describe extra-ordinary events. And if singing for one's own pleasure and the entertainment of one's friends were as normal for most ordinary people as they clearly were ... then there was nothing extra-ordinary about it, and thus little in the way of records of it. Considering songs/music moving between the Old and the New worlds, it must be clear that the first songs sung in North America (with the obvious exception of the songs/music of the 'First Nations' peoples) came from Europe. Equally, we know that songs/music have moved back to the Old world from the New, both by written/printed and recorded methods and by oral means.

If we enquire about the first noted British traditional song or the first noted printed/written song in Britain, we encounter that "We just don't know" answer. The reason is that there are all sorts of pieces now found in oral tradition that occur in early manuscripts but we don't know if they were newly written or taken from oral tradition, nor are we likely to know. One of the carols in Child, Judas (Child 23. Roud 3964),![]() 2 dates back to the 13th century, Chevy Chase (Child 1162. Roud 223) refers to a 14th century battle, but we don't think the ballad was contemporary with the battle, and when it was written we don't know. The Crabfish (Roud 149) goes back into the mists of time as a tale and is known throughout Europe. A handful of songs which were 'traditional' in 1900 are mentioned in the sixteenth century (Frog went a-Courting (Roud 16), Brian O'Lynn (Roud 294), Joan's Ale (Roud 139), Martin said to his Man (Roud 473), Chevy Chase), but that doesn't tell us if they were traditional then, or what else was around. If we turn to America and ask about the first Old World song/tune noted there, or the first example of American song/tune noted in Britain we might expect to be on steadier ground since the time-span is a good bit shorter - but no. Maybe the colonists were too busy with matters of day to day survival to bother with noting down songs, but we can guess that most of them were also current on the Old world at the time. The American War of Independence (1775-1783) certainly produced some new American songs: Yankee Doodle (Roud 4501), Stony Point, The Liberty Song, Free Amerikee, and all have known authors. American song in Britain? Again we really have our work cut out. Probably Minstrel songs of the 1840s, but there must have been stuff before that. Yankee Doodle?

2 dates back to the 13th century, Chevy Chase (Child 1162. Roud 223) refers to a 14th century battle, but we don't think the ballad was contemporary with the battle, and when it was written we don't know. The Crabfish (Roud 149) goes back into the mists of time as a tale and is known throughout Europe. A handful of songs which were 'traditional' in 1900 are mentioned in the sixteenth century (Frog went a-Courting (Roud 16), Brian O'Lynn (Roud 294), Joan's Ale (Roud 139), Martin said to his Man (Roud 473), Chevy Chase), but that doesn't tell us if they were traditional then, or what else was around. If we turn to America and ask about the first Old World song/tune noted there, or the first example of American song/tune noted in Britain we might expect to be on steadier ground since the time-span is a good bit shorter - but no. Maybe the colonists were too busy with matters of day to day survival to bother with noting down songs, but we can guess that most of them were also current on the Old world at the time. The American War of Independence (1775-1783) certainly produced some new American songs: Yankee Doodle (Roud 4501), Stony Point, The Liberty Song, Free Amerikee, and all have known authors. American song in Britain? Again we really have our work cut out. Probably Minstrel songs of the 1840s, but there must have been stuff before that. Yankee Doodle?

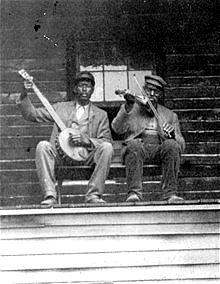

Rod Stradling remembers Sandy Darlington, at a concert in Padstow, having spent a while getting his banjo in tune, responded to mutterings, "You have the tradition - we have the banjo!" A good riposte - but a reversal might provide "You have lots of good and old songs - we have a hundred years of experience of how to perform them." Because we really feel that many of the American songs/tunes aren't in any real way superior to ours, but that it was their performance style that attracted their British audience. And the reason - local radio in America. True, a very few British performers found their way onto British radio, but their performances were simply those that they used in their own local pub, in front of a known audience of a dozen or so. Whereas their American counterparts, singing on local radio, could count on an audience of thousands, and that relatively locally, not to mention financial rewards - which necessitated work and practice! That's not to suggest the Brits didn't work on their songs, or practice them - Harry Cox certainly did! - but his approach was micro subtle, as was appropriate for the cohort of very able singers he knocked about with. Much the same could be said of most British country singers - and those that stood out more did so because of personal charisma than their ability to perform the songs really well. A perfect example is Sam Larner, who was loved for his 'performance' of Sam Larner - and was not, honestly, all that good a singer of some of his songs. And I think - if we're honest - much the same could be said of the other well-known charismatic singers: Fred Jordan; Johnny Doughty; Gordon Hall; Charlie Scamp; Bert Lloyd.![]() 3 The other reason the Americans stood out, and were instantly popular, was - as Tony Engle once said - that they always had a rhythm section ... instrumental accompaniment. We don't know of any convincing argument as to why traditional singers, English particularly, rarely accompanied themselves on fiddles, guitars, banjos as their American counterparts did. Certainly many of them had played instruments in church bands, before Victoria's 'gentrification' programme got under way. Flora Thompson in Lark Rise to Candleford wrote that in the mid-19th century, almost all the instruments in southern English villages had been sold to cover doctors' bills and similar important expenses, and that it wasn't 'til around 1875 when a hike in agricultural wages coincided with mass-produced European instruments becoming available, that home-made music returned to the pub and hearth. Even then, it was almost always for music rather than song accompaniment. This was much the same in Ireland, we think, but rather less so in Scotland.

3 The other reason the Americans stood out, and were instantly popular, was - as Tony Engle once said - that they always had a rhythm section ... instrumental accompaniment. We don't know of any convincing argument as to why traditional singers, English particularly, rarely accompanied themselves on fiddles, guitars, banjos as their American counterparts did. Certainly many of them had played instruments in church bands, before Victoria's 'gentrification' programme got under way. Flora Thompson in Lark Rise to Candleford wrote that in the mid-19th century, almost all the instruments in southern English villages had been sold to cover doctors' bills and similar important expenses, and that it wasn't 'til around 1875 when a hike in agricultural wages coincided with mass-produced European instruments becoming available, that home-made music returned to the pub and hearth. Even then, it was almost always for music rather than song accompaniment. This was much the same in Ireland, we think, but rather less so in Scotland.

However, Scotland has produced many fine singers, especially among the Travelling Community. Singers such as Jeannie Robertson, Bella Higgins, Belle, Cathy & Sheila Stewart, Lizzie Higgins, Geordie Robertson, Lucy Stewart, Betsy Whyte (actually two fine singers shared this name), Jane Turriff, Stanley Robertson, Martha Reid, Blin' Robin Hutchison and Duncan Williamson could run rings around most English Gypsy singers (though English Gypsy singer Phoebe Smith could, I believe, equal any Scottish Traveller when it came to singing). Why should this be the case? It is often said that Scottish people were more literate than their English contemporaries, though this may not be the case with Scottish Travellers. We do know that many Scottish Travellers earned money by singing in public. Perhaps, unlike English Gypsies, Scottish Traveller Society was more tight-knit and that traditions such as singing, music making and storytelling, held more meaning to the Scottish Travellers. You can gain an insight into how this might have been by listening to Duncan Williamson talking about Jack Tales and how they were blueprints for how one should live one's life. Or listen again to Williamson talking about how the tune to the ballad Bonny James Campbell (Child 210, Roud 338) fits the word so perfectly.![]() 4

4

Even when the English began to play instruments again, it was almost always for music rather than song accompaniment. This was much the same in Ireland - John Moulden confirms:

In Scotland the situation was much the same, though Ian Olson mentioned that many Scottish farms were rather bigger than English ones, and farm workers tended to 'live in' in bothies and similar accommodations. Thus, there is a problem here in separating 'traditional' song and its instruments, and other song, for the two would mix in the farms and their kitchens, where piano and expensive instruments such as the accordion and fiddle mingled with the cheaper ones such as concertina, Jew's harp, penny whistle, and mouth organ.

An important difference was the audience size and financial rewards available in the States compared to here. But novelty usually engenders change, so that once the idea of being a professional or semi-professional singer, after the 'folk boom' in the late-sixties and seventies became a possibility, accompaniment became almost mandatory ... and free rhythm and subtlety in accompanied song were in scarce supply throughout these islands.

John Broadwood played the flute and was musically literate, as was his niece, Lucy Broadwood, who was one of the founding members of the Folk Song Society and who became the Honorary Secretary and editor of the Society's annual Journal. Other early Society member including Cecil Sharp, George Butterworth, Percy Grainger and Ralph Vaughan Williams, were also trained musicians and while these people were scouring the English countryside in search of 'folk songs' they were also ignoring much of what their singers were actually singing. We have previously mentioned the fact that when Cecil Sharp gave a lecture in 1903, the year in which he began to collect 'folk songs', he said:

(In the typed notes made for his lecture, Sharp had originally used the term 'drivel' when describing the songs. This is crossed out and the term 'sentimental balderdash' written in its place.)![]() 5

5

Actually, two collectors mentioned above did come across a couple of American songs, though probably without realizing that they were American. In 1903 Percy Grainger collected a version of the song The Birds Upon the Tree (Roud 1863) from the Lincolnshire singer Joseph Taylor, while in 1893 Lucy Broadwood and J A Fuller Maitland included the American song Silly Bill (Roud 442) in their book English County Songs. The song had originally been collected from a singer in Leicestershire by H H Albino.

And this brings us to our first problem, namely that of definition(s). Sharp was clearly aware of a distinction between what he called folk songs and 'other songs' - which his singers clearly knew and enjoyed singing, but which were not to Sharp's taste. Perhaps we should call the latter 'traditional songs'. There has long been a confusion between traditional songs and folk songs. Sharp and his Edwardian co-collectors used the Folk Song definition of:

We would argue that Sharp's definition was actually one for Traditional song rather than Folk song, and we would add to it that such songs and tunes would normally be performed within the community from which they sprang, and (again normally) not for financial gain. Whereas, our definition of a 'Folk song' is a song or tune that the community has taken as its own and used for its own purposes at a particular time. As a consequence, it does not need to be 'anonymous', nor need it originate from within the community, though it will have been selected by it and passed on orally within it. The non-professional criterion will still probably apply. Accordingly, a 'folk song' will exist for a period of time, for a particular community - and was not / will not be a folksong outwith that period or community.

Cecil Sharp and his contemporaries were free with the use of the term 'oral tradition'. In other words, songs were passed from one person to another by word of mouth. But, song texts have been printed on paper almost since the invention of the printing press and these printed sheets - known as broadsides - were sold up and down the length of the country. Edwardian song collectors, such as Cecil Sharp, the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould and Frank Kidson, amassed collections of broadsides which contained the texts of the songs which they were collecting. Clearly, broadsides were a means of transmitting folk song texts among the people who bought the sheets. And yet Sharp and the other collectors seem to have ignored the fact that print played a part in 'folk song' transmission.

We have said that members of the Folk Song Society collected only 'folk songs'. But one contemporary song collector, Alfred Williams, who was not a member of the Society and who was not musically literate, did collect the words to a far wider group of songs, including American ones. The words to some of these songs appeared in his book Folk Songs of the Upper Thames, printed in 1923. These are:

American Songs on British Broadsides belonging to Harry Upton:

Six of these songs - Poor Old Joe, Sweet Bye and Bye, Good Old Jeff, Old Uncle Ned, The Old Oaken Bucket and The Baby on the Shore - are by American composers. We also know the titles to four other songs which were in the Family repertoire - See the Lads With their Lasses Trip the Meadows Along, The Wreath, You're the Kind of Girl that Men Forget and When You and I Were Young, Maggie (Roud 3782) - the latter two songs also being American.

Although this is only a small number of songs, it is interesting that almost half are by American composers and that four of the songs - Poor Old Joe, Good Old Geoff, Old Uncle Ned and The Baby on the Shore are what the Millen Family call 'Plantation songs'. Another name for this type of song is 'Minstrel Songs', a style of song which was once highly popular in Britain. In fact, if we examine the songs mentioned in the various singer's repertoires above, as well as those collected by Alfred Williams, we find the following song titles, some of which are listed more than once:

(Edward Pakenham [1778 - 1815] was the Commander of the British Forces in North America [1814 - 1815]. He died leading his men in the Battle of New Orleans.)

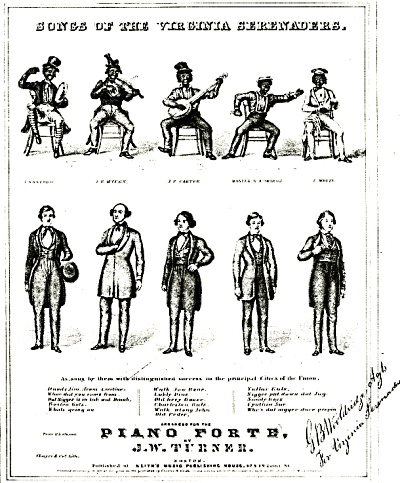

Daniel Decatur Emmett (1815 - 1904) is perhaps best known as the composer of the song Dixie (Roud 18324). In 1840 he began to work in travelling circuses, where he performed as a blackface singer and banjo player. In 1843 Emmett formed the first blackface minstrel troupe, the Virginia Minstrels, which appeared that year at New York's Chatham Theatre. The song Dixie was written in New York sometime around 1859 when Emmett was a member of Bryants Minstrels. It later became the rallying cry for the southern Confederacy, causing Emmett to say, 'If I had known to what use they [Southerners] were going to put my song, I will be damned if I'd have written it.'

Emmett is also credited with writing the song Old Dan Tucker (Roud 390) in 1843 while a member of the Virginia Minstrels. Like Rice's Jump Jim Crow, the song Old Dan Tucker is written in African American vernacular.

And it now seems possible that Daniel Emmett, rather than writing Dixie and Old Dan Tucker himself, had either stolen the songs from black performers or else had used songs by black performers as the basis for his 'own' compositions. Dan Emmett was apparently friendly with the musical Snowden family of Ohio. This family of freed slaves had a band and Emmett almost certainly heard them play. According to the family, 'Dixie' was composed either by Ben and Lew Snowden, or else by their parents Thomas and Ellen Snowden. While Old Dan Tucker, supposedly written about a man called Daniel Tucker who lived in Elbert County, Georgia, was, according to local legend, composed by some of his slave neighbours.

And it now seems possible that Daniel Emmett, rather than writing Dixie and Old Dan Tucker himself, had either stolen the songs from black performers or else had used songs by black performers as the basis for his 'own' compositions. Dan Emmett was apparently friendly with the musical Snowden family of Ohio. This family of freed slaves had a band and Emmett almost certainly heard them play. According to the family, 'Dixie' was composed either by Ben and Lew Snowden, or else by their parents Thomas and Ellen Snowden. While Old Dan Tucker, supposedly written about a man called Daniel Tucker who lived in Elbert County, Georgia, was, according to local legend, composed by some of his slave neighbours.

If it is correct that both Daddy Rice and Daniel Emmett obtained (stole?) some of their songs from black performers, then surely we have a situation which would today be called 'cultural appropriation'. But there is more to it than that. Here we have extremely competent black singers and musicians who were not allowed to perform their own songs and music to a white audience. This material had to be performed by white men who dressed as 'negros' and who had their faces blackened to represent black people. Confused?

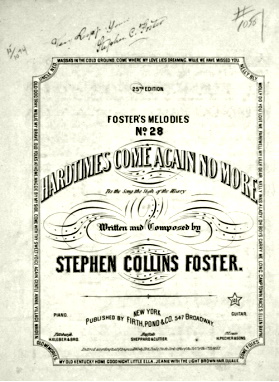

But perhaps the greatest song writer of this genre was Stephen Foster (1826 - 1864) the 'father of American music', whose songs included Oh! Susanna (Roud 9614), Hard Times Come Again No More (Roud 2659), Camptown Races (Roud 11768), Old Folks at Home (Roud 13880), My Old Kentucky Home (Roud 9564), Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair (Roud V288), Old Black Joe (Roud 9601) and Beautiful Dreamer (Roud 24434). So far, nobody has suggested that Foster's songs were composed by anyone but Foster himself. Foster is rightly remembered for his minstrel songs (in 1849 he published a collection of 'Ethiopian Melodies' which contained the song Nelly Was a Lady popularized by the Christy Minstrels), although he also composed many parlour ballads, as did another song writer, Henry Clay Work (1832 - 1884).

But perhaps the greatest song writer of this genre was Stephen Foster (1826 - 1864) the 'father of American music', whose songs included Oh! Susanna (Roud 9614), Hard Times Come Again No More (Roud 2659), Camptown Races (Roud 11768), Old Folks at Home (Roud 13880), My Old Kentucky Home (Roud 9564), Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair (Roud V288), Old Black Joe (Roud 9601) and Beautiful Dreamer (Roud 24434). So far, nobody has suggested that Foster's songs were composed by anyone but Foster himself. Foster is rightly remembered for his minstrel songs (in 1849 he published a collection of 'Ethiopian Melodies' which contained the song Nelly Was a Lady popularized by the Christy Minstrels), although he also composed many parlour ballads, as did another song writer, Henry Clay Work (1832 - 1884).

Work came from an Abolitionist background, saying that his minstrel songs were, 'designed to encourage slaves, rather than ridicule them'. He wrote a number of songs which became popular both in America and in Britain, including: Kingdom Coming (The Year of Jubilo) (Roud 778), Come Home, Father, (Roud 839), Wake Nicodemus (Roud 4988), Marching Through Georgia (Roud 9596), The Ship that Never Returned (Roud 775), My Grandfather's Clock (Roud 4326) and Ring the Bell, Watchman (Roud 13630).

Work came from an Abolitionist background, saying that his minstrel songs were, 'designed to encourage slaves, rather than ridicule them'. He wrote a number of songs which became popular both in America and in Britain, including: Kingdom Coming (The Year of Jubilo) (Roud 778), Come Home, Father, (Roud 839), Wake Nicodemus (Roud 4988), Marching Through Georgia (Roud 9596), The Ship that Never Returned (Roud 775), My Grandfather's Clock (Roud 4326) and Ring the Bell, Watchman (Roud 13630).

One of the first Minstrel troupes to visit Britain was the Virginia Serenaders who arrived in 1843, later followed by Raynor & Pierce's Christy Minstrels, who opened in London's St James Theatre on 3rd August, 1857. The term 'Christy (or 'Christy's') Minstrels comes from a black-face group formed by Edward Pearce Christy in Buffalo, New York, in 1843. Raynor & Pierce's Christy Minstrels included several members from the original America troupe. The Minstrels then moved to the Surrey Theatre and then to the Polygraphic Hall in London's King William Street. In 1859 they were performing in Liverpool's St James's Hall, before touring and performing in various provincial halls. The group then returned to London, before disbanding in 1860. Within a year four new 'Christy Minstrel' troupes were performing throughout Britain. In 1864 one of these troupes began playing at the St James Theatre, the same theatre that the original group had played at in 1857, and such was their popularity that they continued to perform there for 35 years, before retiring in 1904. The Christy Minstrels popularized dozens of songs, including: Blue Tail Fly (Roud 1274), Camptown Races (Roud 11768), Grape Vine Trot, Jump Jim Crow (Roud 12442), Jordan is a Hard Road to Travel (Roud 12153), Oh! Susanna (Roud 9614), Old Bob Ridley (Roud 753), Old Dan Tucker (Roud 390), Old Folks at Home (Roud 13880), Old Joe Clark (Roud 3594), Old Johnny Boker (Roud 1329 or 353), Old Zip Coon (Roud 328), The Ole Grey Goose (Roud 3619), Polly Wolly Doodle (Roud 11799), Turkey in the Straw (Roud 4247) and Year of Jubilo (Roud 778).

Such was the popularity of the Minstrels in Britain that British music publishers were soon printing both words and music to these songs. For example, John Leng & Co. of Dundee, the publishers of the Dundee Advertiser issued 'Nigger Minstrel Songs' as 'The English People's Songs no. 3'. The songbook, featuring a drawing of a backface minstrel playing a banjo on the cover, cost one penny and contained the following songs. In the Hazel Dell (Roud 13780), I'se Gwine Back to Dixie (Roud 18324), John Brown's Body (Roud 771), Massa's in de Cold, Cold Ground (Roud V8653), The Old Folks at Home (Roud 13880), Lily Dale (Roud 2819), The Old Kentucky Home (Roud 9564), Wait for the Wagon (Roud 2080, 2835 or 3716), Good Old Jeff (Roud 1740), 'Tis but a Little Faded Flower (Roud 248521), Hard Times, Come Again No More (Roud 2659), Oh! Dem Golden Slippers (Roud 13941), Sweet Genevieve (Roud 13645), Poor Old Joe (Roud V46032 or 9601), Belle Mahone (Roud 13636), Marching Through Georgia (Roud 9596), White Wings (Roud 1753) and The Cottage By the Sea (Roud 4327). The songbook is undated, but as the song 'Golden Slippers' was written in 1879, the songbook cannot predate this date.

Such was the popularity of the Minstrels in Britain that British music publishers were soon printing both words and music to these songs. For example, John Leng & Co. of Dundee, the publishers of the Dundee Advertiser issued 'Nigger Minstrel Songs' as 'The English People's Songs no. 3'. The songbook, featuring a drawing of a backface minstrel playing a banjo on the cover, cost one penny and contained the following songs. In the Hazel Dell (Roud 13780), I'se Gwine Back to Dixie (Roud 18324), John Brown's Body (Roud 771), Massa's in de Cold, Cold Ground (Roud V8653), The Old Folks at Home (Roud 13880), Lily Dale (Roud 2819), The Old Kentucky Home (Roud 9564), Wait for the Wagon (Roud 2080, 2835 or 3716), Good Old Jeff (Roud 1740), 'Tis but a Little Faded Flower (Roud 248521), Hard Times, Come Again No More (Roud 2659), Oh! Dem Golden Slippers (Roud 13941), Sweet Genevieve (Roud 13645), Poor Old Joe (Roud V46032 or 9601), Belle Mahone (Roud 13636), Marching Through Georgia (Roud 9596), White Wings (Roud 1753) and The Cottage By the Sea (Roud 4327). The songbook is undated, but as the song 'Golden Slippers' was written in 1879, the songbook cannot predate this date.![]() 10

10

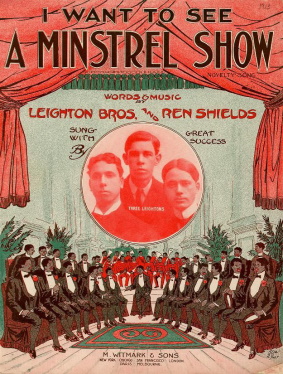

With the availability of such printed material it was only natural that British performers, both amateur and professional, should take up the Minstrelsy mantle. For example, in the run up to the Great War one person from the Kentish village of Woodchurch could say, "Every year during the dark nights around Christmas time, we were visited by the Glee singers and the Nigger minstrels - all local fellows."![]() 11 Professional stage minstrels included G H Chirgwin (1854 1922), who was known as 'the White-Eyed Kaffir', and G H Elliott (1882 - 1962), known as 'the Chocolate-Coloured Coon'.

11 Professional stage minstrels included G H Chirgwin (1854 1922), who was known as 'the White-Eyed Kaffir', and G H Elliott (1882 - 1962), known as 'the Chocolate-Coloured Coon'.  Elliott based his act on that of an American performer, Eugene Stratton (1861 - 1918) who had come to England in 1880. Stratton's most popular song, Lily of Laguna (Roud V8513), was taken up by Elliott. Today we rightly condemn 'blacking up', but it is indicative of its one-time popularity when we remember that G H Elliott appeared in three Royal Variety Performances (in 1925, 1948 and 1958).

Elliott based his act on that of an American performer, Eugene Stratton (1861 - 1918) who had come to England in 1880. Stratton's most popular song, Lily of Laguna (Roud V8513), was taken up by Elliott. Today we rightly condemn 'blacking up', but it is indicative of its one-time popularity when we remember that G H Elliott appeared in three Royal Variety Performances (in 1925, 1948 and 1958).

And popularity for the Minstrels was such that British Minstrel groups were recorded, one such group being the Zono Minstrels who cut six sides in 1913. At least one song recorded by the Zono Minstrels, De Old Banjo (Roud 31136) was still being sung in the 1980s by the Kentish singer Charlie Bridger.![]() 12

12

Popular songs, such as those by Stephen Foster and Henry Clay Work, were also sold by American and British publishers who sold the songs, words and music, on A4 sized folios, usually with an illustration on the front cover. In America the trade for this type of printing centered around the so-called 'Tin Pan Alley', in New York's Manhattan district. In the mid-19th century there was little copyright consistency in the world of American music publishing. Publishers could, and often did, use fictitious names for song writers and composers, thus increasing their profits and it was not until the 1890s, when publishers began congregating together in 'Tin Pan Alley', that this practice ceased.

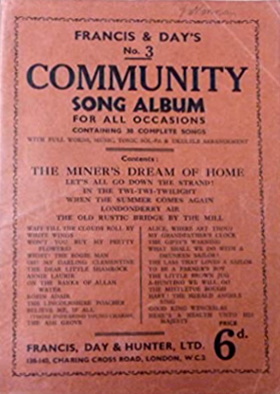

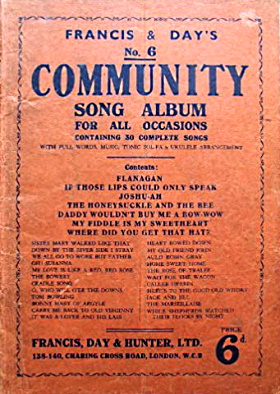

This was a time when many American (and British) homes had a piano and sheet music was in demand. Parlour ballads, along with hits from Broadway musicals and the American Music Hall, and other forms of popular music, were printed and deals struck with British publishers who gained the rights to publish American songs and music in Britain. One British publisher, Francis & Day (later Francis, Day & Hunter) printed numerous 32 page folios with titles such as Album of Famous Old Songs, Album of Old Time Favourites, Community Song Albums, Plantation and Minstrel Songs and Hillbilly Album.![]() 13 The two Community Song albums (nos. 3 & 6 and dated to c.1928 - 30) shown here contains many songs which have been recorded from traditional singers. These include: The Miner's Dream of Home (Roud 1749), The Old Rustic Bridge by the Mill (Roud 3792), Wait Till the Clouds Roll By (Roud 9088), Won't You Buy My Pretty Flowers? (Roud 12906), The Dear Little Shamrock (Roud 3769), On the Banks of Allan Water (Roud 4260), The Lincolnshire Poacher (Roud 299), My Grandfather's Clock (Roud 4326), The Gypsy's Warning (Roud 1764), A-Hunting We Will Go (Roud 12972) and While Shepherd's Watched Their Flocks by Night (Roud 936). A number of these songs, together with others in the Francis & Day folios, are by American composers.

13 The two Community Song albums (nos. 3 & 6 and dated to c.1928 - 30) shown here contains many songs which have been recorded from traditional singers. These include: The Miner's Dream of Home (Roud 1749), The Old Rustic Bridge by the Mill (Roud 3792), Wait Till the Clouds Roll By (Roud 9088), Won't You Buy My Pretty Flowers? (Roud 12906), The Dear Little Shamrock (Roud 3769), On the Banks of Allan Water (Roud 4260), The Lincolnshire Poacher (Roud 299), My Grandfather's Clock (Roud 4326), The Gypsy's Warning (Roud 1764), A-Hunting We Will Go (Roud 12972) and While Shepherd's Watched Their Flocks by Night (Roud 936). A number of these songs, together with others in the Francis & Day folios, are by American composers.

Other British song folios were published by Lawrence Wright (also known as Horatio Nicholls), Campbell Connelly and Felix McGlennon. And there were other collections, such as The Scottish Students Song Book, The News Chronicle Song Book and The People's Song Folio all of which contained the words of songs which were highly popular.

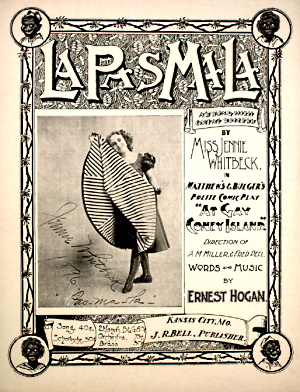

In 1899 the composer Scott Joplin published his Maple Leaf Rag. Three years later he published one of his most popular tunes, The Entertainer. Joplin was not the first ragtime composer; one Ben Harney, from Kentucky, had previously published his You've Been a Good Wagon, But You Done Broke Down in 1896 and this is sometimes described as the first ragtime tune, so named because of its ragged rhythm. However, there is another song, La Pas Ma La, which had appeared in 1895. It was performed by Ernest Hogan, a Minstrel performer with the Georgia Graduates, and suggests a link between the Minstrel Shows and the birth of Ragtime music. Ragtime tunes were printed as sheet music and the vogue for this type of music lasted until about 1919, when Jazz recordings were becoming popular both in America and in Britain. American Jazz, in turn, inspired the growth of British Dance Bands, many of which had featured singers, several of whom sang the latest American pop songs.

In 1899 the composer Scott Joplin published his Maple Leaf Rag. Three years later he published one of his most popular tunes, The Entertainer. Joplin was not the first ragtime composer; one Ben Harney, from Kentucky, had previously published his You've Been a Good Wagon, But You Done Broke Down in 1896 and this is sometimes described as the first ragtime tune, so named because of its ragged rhythm. However, there is another song, La Pas Ma La, which had appeared in 1895. It was performed by Ernest Hogan, a Minstrel performer with the Georgia Graduates, and suggests a link between the Minstrel Shows and the birth of Ragtime music. Ragtime tunes were printed as sheet music and the vogue for this type of music lasted until about 1919, when Jazz recordings were becoming popular both in America and in Britain. American Jazz, in turn, inspired the growth of British Dance Bands, many of which had featured singers, several of whom sang the latest American pop songs.

Inventor Thomas Edison produced several different forms of recording machines in the 1870s and cylinder records and, slightly later, 78 rpm records were soon being sold to the public. It wasn't long before Music Hall singers were recording their songs for posterity and Michael Yates has previously discussed this in a short article The Other Songs - Musical Traditions Enthusiasms article, number 40 (dated 2003). This article, which considers how songs recorded by British Music Hall singers entered the repertoires of English traditional singers, does not refer to recordings made by American performers in America.

Many early American records were brought into Britain by merchant sailors and this may explain why ports, such as Liverpool, became centres for American music in Britain.

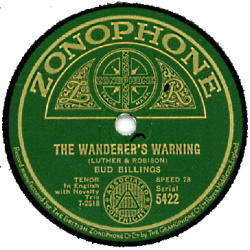

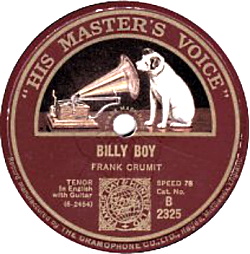

American recording companies soon joined up with British companies, such as Decca, Edison Bell Winner, HMV, Panachord, Parlophone, Regal/Regal Zonophone, Rex and Zonophone, so that their recordings could be released in Britain. In some cases, American performers made recordings in London while touring the country. For example, the early country singer Carson Robison, or his accompanying musicians, recorded a total of 83 tracks in London in 1932, 1936 and 1939. Many of Robinson's recordings entered the British traditional song repertoire.

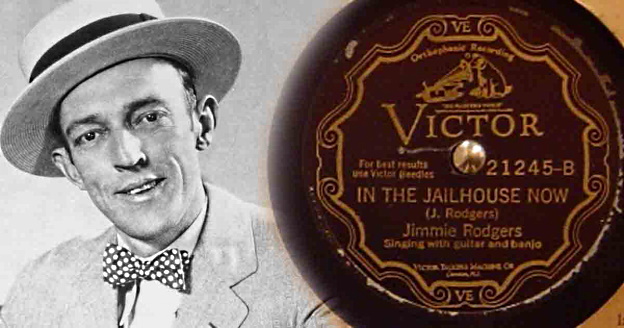

It seems that during the early 1930s people began to learn songs from records, rather than from printed music sheets. English Gypsy singers seem to have been especially drawn to recordings by early Country singers, such as Gene Autry and Jimmie Rodgers. On the 3 CD set Wait Till the Clouds Roll By (Musical Traditions records MTCD518-0) you can hear California Blues performed by both Autry himself and by the young Gypsy singer Derby Smith. You can also hear Jimmie Rodgers singing Rock All Our Babies to Sleep (Roud 4378), He's in the Jailhouse Now (Roud 18801) and Mother, Queen of my Heart (Roud 9708) alongside Gypsy versions of these songs sung here by Doris Davies, Derby Smith and Levi Smith.

True, one or two people did continue to look for songs, but this was not the norm and most members of the EFDSS appeared to be more interested in dance, rather than in song. One singer of note, the Welshman Phil Tanner, was recorded by Columbia Records at the request of Maud Karpeles, who had been Cecil Sharp's secretary and was later a leading light in the EFDSS. Four songs were recorded in November, 1936, and issued commercially in the following year. These were:

Another fine singer, Harry Cox of Norfolk, was recorded in 1934, this time by Decca Records, and again at the request of the EFDSS. Cox travelled to London by train, where he was met by the Anglo-Irish composer Ernest John Moeran, who had first encountered Cox in the early 1920s when Moeran was collecting folk songs in East Anglia. Two songs were recorded, Down by the River Side (Roud 291) and The Pretty Ploughboy (Roud 186), and issued on a Decca 78 rom record which was available from the EFDSS.

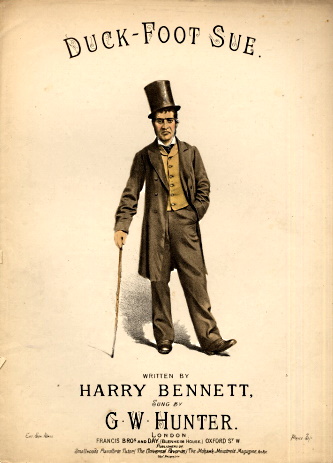

Some songs were also recorded by the BBC at The Eel's Foot pub at Eastbridge, Suffolk. In 1938 and 1939 A L Lloyd took a BBC team to the pub, while in 1947 Ernest John Moeran returned to East Anglia with another BBC team. Moeran recorded four 'folk songs', though a couple of songs which were recorded by A L Lloyd, Duck Foot Sue (Roud 9553) written by the American Harry Bennett, and the American IWW (International Workers of the World) song Poor Man's Heaven (Roud 16821), were American in origin. No doubt A L Lloyd , a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, was delighted to find the IWW song being sung among rural Suffolk labourers.

This, we feel, was an important turning point in the history of song collecting in England. Members of the Folk Song Society were often, socially speaking, far removed from the people who sang songs to them and Lloyd, who came from a working-class background in London, had been raised in a very different society from that of the Edwardian collectors.

This, we feel, was an important turning point in the history of song collecting in England. Members of the Folk Song Society were often, socially speaking, far removed from the people who sang songs to them and Lloyd, who came from a working-class background in London, had been raised in a very different society from that of the Edwardian collectors.

During World War Two a large number of American troops were stationed in Britain prior to the D Day landings in 1944. American servicemen were encouraged to mix with locals and there were often dances arranged on American bases where locals were invited to attend. Many servicemen also enjoyed drinking in local pubs. Sussex singer Harry Upon (mentioned above) told about singing the song Canadee-I-O (Roud 309) in a pub one night in 1940 and a visiting Canadian airman joined in. It was obvious to Harry that the Canadian knew the song, which was a puzzle to Harry because he had previously thought that only himself and his father knew the song.![]() 15 It seems almost certain that some English singers would have picked up America songs from the visiting troops. On one occasion Michael Yates was told by a person in Kent that he had heard two black American servicemen playing guitars and singing blues in a Kentish field just prior to D Day.

15 It seems almost certain that some English singers would have picked up America songs from the visiting troops. On one occasion Michael Yates was told by a person in Kent that he had heard two black American servicemen playing guitars and singing blues in a Kentish field just prior to D Day.

In the early 1950s A L Lloyd and fellow Marxist Ewan MacColl were responsible for starting what became known as 'the second folk revival' when they led the way by opening folk clubs and recording albums of folk songs. Further impetus was given by the BBC who, in 1953, launched a weekly radio program called 'As I Roved Out'. The BBC wished to gather together recordings of British and Irish dialect, which could then be used by actors who were unable to lean directly from dialect speakers. It was soon realized that one way to collect such material was to record the speakers singing songs along with their speech. And so As I Roved Out was born. Collectors, such as Peter Kennedy, of the EFDSS, Alan Lomax, Hamish Henderson, Sean O'Boyle and Seamus Ennis were sent out with EMI portable tape recorders and their finds were broadcast on the weekly program. The general public, it seems, liked the recordings and many listeners were soon writing in to the BBC telling of other singers. Again, though, much of the material gathered fitted the Cecil Sharp definition of 'folk song'.

Although the BBC recording scheme officially began in 1953, there had been activity just prior to this date. In late 1951 a person wrote to say that his mother, Cecelia Costello, was a fine singer and knew a number of songs. Mrs Costello was visited in November 1951 by Marie Slocombe of the BBC and Patrick Shuldham-Shaw a musician and member of the EFDSS. The following thirteen songs were recorded:

The folk clubs and folk festivals of the 1950s and early 1960s encouraged many people to seek out singers and musicians who were still from a 'traditional' background. Very few of these new collectors were trained musicians, but were motivated more by an interest in hearing and preserving what was actually being sung and played at that time. Researcher George Frampton had this to say about John Howson of Veteran Recordings in Suffolk:

Some of the collectors were carrying out 'field work' as part of an academic requirement. Most, though, were doing it purely out of love for the music and for the people who so willingly gave us their songs.

Using just about affordable and portable semi-professional recording machines, some of their recordings appeared on LP records issued by Topic Records of London. Such albums were restricted to just over 40 minutes of playing time and there was still a tendency to include only the 'folk songs' that were in their singer's repertoires. Other songs, Music Hall and Parlour Ballads for example, were often omitted. It was only with the arrival of the CD disc, which could carry almost 80 minutes of recordings, that much wider repertoires were able to be included. For example, Walter Pardon's first LP A Proper Sort (Leader LED063) contained the following eleven songs, all but one of which fall within Cecil Sharp's folksong definition:

In other words, English collectors from the early 1960s onwards have not limited their collecting solely to what Sharp et al perceived to be 'folk songs', and this has made a big difference in understanding just what actually constitutes the English 'folksong' repertoire.

At one point, an elderly Gypsy woman came into the room carrying a metal jug. Her pinafore reminded me of something that my maternal grandmother used to wear. She was holding the jug with her forearms, her hands, crippled with arthritis, were unable to hold the vessel. This was May Bradley. May's husband had been banned from the pub for fighting and May, who lived across the road from the pub, would come in two or three times a night to have her jug filled with cider for her husband to drink at home.

"Sing us a song, May", somebody asked, and the room became quiet. I will never forget the song (Roud 127), with it opening lines:

As I listened intently to May's song, I knew exactly what it was that had so inspired Ralph Vaughan Williams to become such a magnificent composer.![]() 18

18

When the Edwardian folk song collectors began searching for 'folk songs' they, sadly, ignored much that was actually being sung by 'folk singers'. Perhaps some collectors dreamt of a time when there had been a 'pure' folk society, one where 'folk songs' were the only type of songs which were sung by 'the peasantry' - a term beloved by those same collectors. In truth, there was probably no such time. People have always had eclectic tastes when it came to songs and singing and, hopefully, we will continue to do the same today.

It should come as no surprise to find so many American songs being sung in Britain today and in the last couple of hundred years. The surprise is that so little attention has been paid to this phenomenon by musicologists in the past. Today we still have a chance to examine and try to understand just what has been happening in the 'folk' world. Tomorrow might just be too late.

Michael Yates & Rod Stradling - Swindon & Stroud. 2000.

2 Child refers to 'The English and Scottish Popular Ballads' by Francis James Child (various editions) and Roud refers to the 'Roud Index of Songs' - copy available on-line at the Vaughan Williams Library website.

3 Co-author Michael Yates does not agree with this sentence.

4 These recordings may be heard on the CD 'Travellers' Tales - volume 1', Kyloe Records CD 100.

5 Printed in the booklet which accompanies the CD set 'Wait Till the Clouds Roll By' (MTCD518-0).

6 Musical Traditions article 27, 'Sing, Say or Pay. East Suffolk Music & Song' by Keith Summers (1999).

7 Harry Upton can be heard on two Musical Traditions CD - ' Why Can't it Always be Saturday?' (MTCD371) and 'I Wish There Was No Prisons' (MTCD372).

8 Suffolk musician Jock Hardwick told Keith Summers that when he lives with his parents in Ipswich his father would frequently attend the Music Hall, and would sing the songs that he had heard there when he got home. Musical Traditions Article no. 27 'Sing, Say or Pay'. (1999).

9 Alan Jabbour, James Reed & Bertram Levy play a very good version of the tune 'Jump Jim Crow' on the 2002 CD 'A Henry Reed Reunion'. Bertram Levy Music Productions, no issue number.

10 A number of once common-place words, such as n-----, are today rightly deemed to be offensive. We have tried to limit the use of such words in this article, but, where used, they are included purely for historical accuracy. They are not included to imply any form of racial slur.

11 Booklet notes to the CD 'Down Yonder Green Lane - The Millen Family' . Open CD003. Where 'blacking-up' has occurred in local traditions, such as Mumming Plays or Morris Dancing, we believe that the tradition-bearers did not do so to indicate that they were referring to people of colour. For example, The Britannia Coco-Nut Dancers from Bacup in Lancashire believes that their black faces stem from the fact that their dances originated with local coalminers who had black faces from their work. Local people would have understood this. If there is a ritual element behind Morris Dancing (and this is still a subject of debate!) then it may be that in the traditions which feature black faced dancers, then these practices were used to disguise the dancers. It has also been suggested that, by being disguised, any mischief done during the performances and afterwards, due to drink having been taken, would not adversely affect the subsequent employment opportunities of the participants. Both reasons are probably equally valid. Certainly, it is known that the Mumming plays once performed in many of the Caribbean islands featured black participants 'whiting up' by rubbing their faces with white clay, undoubtedly for the same reason that English Mummers and Morris men blacked up. And if white clay was a quick and simple way to make a black face unrecognizable, so was soot for white faces

12 'Playing on the Old Banjo' sung by Charlie Bridger of Stone-in-Oxney, Kent, can be heard on the Musical Traditions CD 'Won't You Buy My Pretty Flowers?' (MTCD377). For more on Minstrelsy, see Dale Cockrell's 1997 book 'Demons of Disorder: early blackface minstrels and their world', Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

13 We are indebted to George Frampton for his article 'Sheet Music as a Research Tool for Traditional Song'. Musical Traditions Enthusiasms number 32. 2002.

14 Phil Tanner's recordings may be heard on the CD 'The Gower Nightingale'. Veteran VT145CD.

15 Harry Upton can be heard singing Canadee-I-O on the Musical Traditions CD Why Can't it Always be Saturday (MTCD371).

16 Claims by Peter Kennedy that he recorded Mrs Costello three months before she was visited by Slocombe & Shuldham-Shaw appear to be spurious.

17 Musical Traditions Enthusiasms number 32.

18 Michael Yates. Extract from an unpublished memoir. May Bradley can be heard singing The Leaves of Life on the Musical Traditions CD MTCD349.

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |