Article MT081 - from Musical Traditions No 2, Early 1984.

... and a classless culture?

"Now I think the true crisis in cultural theory in our own time, is between this view of the work of art as object and the alternative view of art as a practice." p.15.

"...we should look not for the components of a product but the conditions of a practice." p.16.

"This means, of course, that we have no built-in procedure of the kind which is indicated by the fixed character of an object. We have the principles of the relations of practices, within a discoverably intentional organization, and we have the available hypotheses of dominant, residual and emergent." p.16.

"I have next to introduce a further distinction, between residual and emergent forms, both of alternative and of oppositional experiences, meanings and values which cannot be verified or cannot be expressed in the terms of dominant culture, are nevertheless lived and practised on the basis of the residue ... cultural as well as social ... of some previous social formation." p.10.

"But our hardest task theoretically, is to find a non-metaphysical and non-subjectivist explanation of emergent cultural practices. Moreover, part of our answer to this questions bears on the process of persistence of residual practices." p.12.

From Raymond Williams - Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory - New Left Review

The strongest musical styles of the twentieth century have come from the formation of the working class in various countries - Afro-American blues, jazz, rhythm 'n' blues, gospel; white American country & western: Trinidadian calypso; Jamaican reggae; Greek laika or rebetika; Argentinian tango; Brazilian samba and bossa; Cuban and Puerto Rican Latin; Polish-American Polka.  In each of these styles, class factors (especially the relative importance of lumpen life styles and values) and various ethnic traditions blend differently, but each synthesis has the power to evoke strong responses across class lines and ethnic lines so that the effort to commodify those styles is usually unrelenting soon after their birth.

In each of these styles, class factors (especially the relative importance of lumpen life styles and values) and various ethnic traditions blend differently, but each synthesis has the power to evoke strong responses across class lines and ethnic lines so that the effort to commodify those styles is usually unrelenting soon after their birth.

The perspective that shapes our approach to the polka has been built upon Charles Keil's studies of Afro-American blues (1962-65) and Yoruba Juju (1965-1967) and Angela Keil's work (1970-72) on the life of Marcos Vamvakaris, father of Greek laika or bouzouki music, and on a continuing interest in a number of the other styles listed above. From these studies it is clear that the former peasants who became the working class not only survive and build the industrial economy, the cities, and transportation networks, and so forth, but they also create distinctive cultures.

A few generalisations about these three styles may help to suggest a framework for closer study. It is sometimes easy to forget that urbanisation in this century is an unprecedented phenomenon. Since 1900 over two million Greeks have moved to Athens, almost a million Yoruba have moved to Ibadan, a million blacks have moved to Chicago. All those people once lived on the land in a state of delicately balanced oppression, an oppression made tolerable by its very predictability, by respect and solidarity within and between families, by pride in locality, distrust of cities, by less articulate values that have to do with the working by hand in natural surroundings. Through a combination of industrial processes that seemed inevitable until very recently, the peasantries of the capitalist world were forced off the land and pushed to the bottom of the cities, there to suffer a kind of predictable, and therefore initially near total, oppression. The catalogue of slum problems is long, familiar, but always worth reciting: unemployment for men and women and children; new 'freedoms' to consume and be consumed; a breakdown of traditional family and kinship patterns, adultery, illegitimacy, prostitution; malnutrition and diseases; dependence on alcohol and drugs; crowded housing and high incidence of crime; alienation, anomie and other high-sounding names for despair.

Conservative peasant values do not serve at all in this environment except to make despair total, humour desperate, and song lyrics that will last as long as the human spirit struggles to survive.

Afro-American blues took shape as a style very early in this century, became recognisable just after 'World War I, but has only reached a peak of popularity outside the Afro-American cultural context within the past decade. Though most scholarship has the blues originating in the rural south, it seems clearer all the time that style qua style crystallised in the cities and the model was secondarily disseminated to the rural areas where more idiosyncratic versions of it developed. In the cities the blues have passed through various stages and have been passed into the mainstream of American and world music as 'rhythm and blues' or 'soul music' - a blend of secular blues, sacred gospel and black art music or jazz. Once a basic reference point for black Americans migrating from country to city, it has become everyone's music. Musically, the urban jungles of Memphis and Chicago have not produced wild cries, turbulent rhythms, and complex structure but a unified style of great simplicity, the 12 bar blues: a four bar call and response pattern repeated a second time for clarity and intensity, resolved in the final four bars underlying harmonic and rhythmic pattern rudimentary; melodic patterns very uniform though subtly inflected; meter 4/4.

Yoruba juju style grew up in the cities of western Nigeria during the 1920s, the name 'juju' an ironic reference to the church harmonies and the Salvation Army source of the initial instruments used - tambourine, cymbals, triangle. The practitioners of the style have always been semiliterate migrants to the big cities 'juju' label. It is only during the past 15 years, however, that this style has emerged to dominate the Yoruba musical scene. The popular juju bands of today feature call/response singing and electric guitar counterpoint over a complex foundation provided by eight or nine drummers. This music from the slums of Ibadan and Lagos presents another tightly integrated style. Each of the eight or nine drummers plays a relatively simple rhythm, taken in isolation, but the nine combined create a sound that has the texture of tightly woven cloth and the buzzing, blooming confusion of an African market place under control. They sing in the sweetest church harmonies of a traditional culture torn apart, of the good old values people should live by. Leader and chorus, guitar and percussion, always balance perfectly and gentle dance movements are built upon a dignified shuffle.

Greek rebetika or laika style is more familiarly known as bouzouki music, as in Never on Sunday or Zorba and the Olympic Airways television commercials. Here again the style was created by peasants, refugees, migrants to the ports and slums of urban Greece during the period immediately following the first World War.  And again, forty years of stylistic evolution has taken place before the music achieves wide popularity throughout Greece and some acceptance outside as well. From the hashish dens, jails, brothels, and army barracks of Piraeus and Athens comes the Zembekiko, the fundamental dance meter of laika style, slow, measured, stately, eighteen very carefully accented eighth notes to the bar. The bouzouki players are always in perfect unison, the singing is precise, the dancing a precious balancing of the bodily scales. The total effect is Apollonian in the extreme.

And again, forty years of stylistic evolution has taken place before the music achieves wide popularity throughout Greece and some acceptance outside as well. From the hashish dens, jails, brothels, and army barracks of Piraeus and Athens comes the Zembekiko, the fundamental dance meter of laika style, slow, measured, stately, eighteen very carefully accented eighth notes to the bar. The bouzouki players are always in perfect unison, the singing is precise, the dancing a precious balancing of the bodily scales. The total effect is Apollonian in the extreme.

Perhaps for the lack of immediate continuing pressures from other cultures, Greek urban music is the least changed in its latest evolutions. There has been a gradual smoothing out of rough edges, more European harmonies, some melodic borrowings from Indian film music, and perhaps an overall loss of vitality despite a relatively recent revival of interest in the 1930s composer singers.

In stark comparisons, juju has accomplished a drastic return to its origins. Beginning as an Afro-Western synthesis with melody instruments like guitar, mandolin, piano, and even violins predominant in the earlier recordings, juju has dropped the Western instruments leaving the guitar alone, the Salvation Army-borrowed tambourine, triangle, and cymbals were put aside while more drums were added decade by decade until the components of the traditional Yoruba drum family were reunited. Once all singing was in standard Yoruba, now each band sings in a regional dialect, often using idioms incomprehensible to Yoruba from other regions. The push back to localised roots continues with each bandleader seeking out the proverbs and rhythmic patterns unique to his district or town of origin. Even high-life, once a pan-Nigerian or pan-West African style, was re-acculturated during the 1960s. Pidgin English and standard instrumentation have been cast aside by the most popular bands whose words and music are distinctively Iboj, Yoruba, Kalabari, Bini, etc.

Afro-American music, finally, has an extraordinarily complex development because of the accelerated pace of cultural homogenisation, provoking musicians to repeatedly attempt to reassert the autonomy of their audiences. Every white theft of a black style - Dixieland, then swing, then rhythm and blues, has forced black Americans to delve deeper into their own resources in order to shape a new style they can call their own. Waves of black church music have been absorbed by American popular song, and Afro American innovators are looking to the Caribbean and Africa itself for nourishment.

The Residual is the Emergent

The most interesting fact about Polish American polka style in relation to blues, laika, and juju is that it has never been researched; bourgeois (and radical) scholarship has shown zero interest. It is still a proletarian style at roughly the point where blues, juju, and laika were in the early 1950s. At this stage of our observation, the polka style can better be described than analysed in a parallel manner.

We can begin, however, with some features that the Polish-American polka music shares with the other styles described:

- The creativity of the relatively new urban dweller is especially obvious in the presence of a new musical style - something that can only be created by generations of intense and shared experience - and is confirmed by corresponding styles of dance, dress and speech; the aural and bodily crafts or 'ABC' of proletarian culture.

- The creation of these styles is a living continuation, an active development and constant reworking of peasant traditions. This process has nothing in common with, and is really opposed to, the bourgeois passion to preserve or recreate or create 'folk' culture and 'folk' lore.

- But the new style is based not only on reworking older forms but also upon the incorporation of contemporary elements and forces like electricity. Again, this process has no concern for the 'authenticity' or 'purity' of the kind that provides almost a raison d'Ítre for the bourgeois connoisseur. It seems to resemble the joyful and catholic interest in food of the robust organism whose digestive process absorbs all that is of use and swiftly eliminates everything not needed.

- These styles both confront and retreat from urban social reality and the conditions of life defined by wage labour. The lyrics speak occasionally of the slums and brutal working conditions. More often the avenue of escape - drink, travel, 'good times' - are celebrated. Most content is focused on the struggle to make a life, to strengthen love, family and friendship ties while under the attack of an all-usurping commodity economy.

- The proletariat achieves its styles through the preservation of the communal forms of social creation and the ingrained methods and skills and sensibility of the oral tradition. It is important for those of us who have learned to associate art, and certainly great art, with great individual artists to keep in mind that this is a rather recent twist in history and that the great traditions of knowledge and expression prior to the bourgeois period come out of co-operative social efforts that in turn depended on their embeddedness in the thick life processes of the community. In the final analysis, vitality of style depends upon the health of the community.

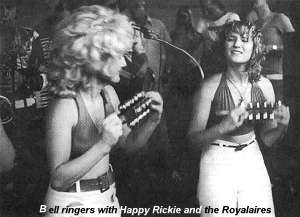

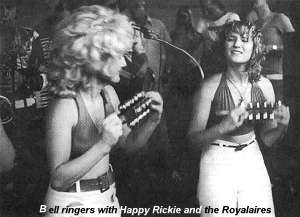

Polka music is alive and well in the Buffalo community because a group of less than a thousand Polish-American working people have a passion for the polka - as music, as a dance, as a party that goes full blast for all ages and both sexes, for family and friends, where time is suspended in a state of happiness. The rest of the Polish American community dances the polka at weddings, at parish dances and lawn fetes and may listen to it on the weekends from one of the four local disc jockeys on the small stations catering to special audiences. But it is the hard core of a dozen top bands, their families and fans, that support the polka as their primary process of recreating themselves, who keep the music honed to perfection and bring it to the rest of the community.

The economic base for polka events is built by this hard core within the community. Big record companies, big radio and the TV networks are not interested in the polka. So, bands make their own records and sell them from the band stand; band leaders become disc jockeys on local stations.

To describe the always-evolving style of the bands is to probe a yet little-understood history. Generally, we can see a movement from 'Eastern style' to 'Chicago' or 'Honky' style. As recently as fifteen years ago all the bands in the Buffalo area played the 'Eastern' style. Twenty-five years ago this was just about the only Polish American music to be heard on records and the large bands on the East coast reigned supreme. the legendary promoter 'Big Ziggy' Zywicki brought them all to Buffalo's ballrooms where they mixed polkas, obereks, waltzes, and good swing to the delight of packed houses. It was a golden era and one of fine musicianship. Most everyone read music, arrangements were very tricky, tempos were very brisk and bands were admired for the crisp articulation in the saxophone section, impossible clarinet duets, perfect unison from the triple tonguing trumpet players.

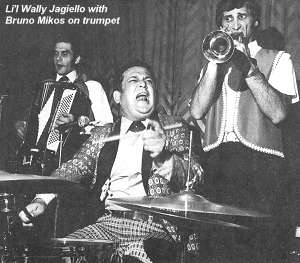

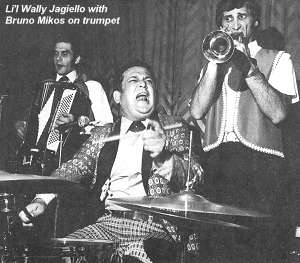

The last great Eastern band - the Connecticut Twins, Jas and Stas - perfected the style, reduced the size of the band from 10 to 12 pieces to six  by introducing amplification and provided the model for many Buffalo bands in the 1950s. But by then Li'l Wally Jagiello from Chicago was knocking at Buffalo's door.

by introducing amplification and provided the model for many Buffalo bands in the 1950s. But by then Li'l Wally Jagiello from Chicago was knocking at Buffalo's door.

At first the Eastern establishment laughed at the slow tempo, the loose phrasing, the whining squeezebox concertina, the unembarrassed vocals 'from the heart' and, above all, the one man band aspect of the whole thing. For Li'l Wally was thumping the bass drum with his foot, squeezing the concertina, and singing simultaneously without a note of music in sight. How does a Symphony musician feel when he hears his first bluesman, from Mississippi?

Polka disc jockeys returned Wally's first records marked 'defective', 'too slow', or 'go practice some more'. But somehow, and no one I've talked to is very clear about the how and why of it, Li'l Wally Jagiello caught the ear of the people with hit after hit in a musical idiom that seems to have its roots deep in the Goral Mountains and small towns of Galicia Province in Poland.

Not that this is Polish music - you won't find either Chicago or Eastern style polkas in Poland any more than you find blues and jazz in Africa. But the music developed by Wally, Eddie Zima and many others along Division Street or 'Polish Broadway' in Chicago during the 1940s does echo the village of 19th century Poland in a way that the flash and perfection of Eastern style do not. In the hands of the Chicago musicians like Marion Lush and Eddie Blazonczyk, the 'Chicago' or 'honky' or 'dyno' style  has proven itself dynamically responsive to the changing tastes and needs of Polish-American communities across the nation.

has proven itself dynamically responsive to the changing tastes and needs of Polish-American communities across the nation.

The massive shift from Eastern to Chicago style polkas began in Buffalo in the early 1960s and today 90 per cent of the polkas you will hear in greater Buffalo are based in the Chicago tradition.

Whatever the style, every polka event is built by polka people. The wedding is perhaps the prototype: find and rent a hall, pick a caterer or recruit family and friends to cook; buy the food; hire bar tenders; buy booze; pick the band or bands and pick a day when the bands you want are free; send out invitations (or put up posters, pass out slingers, sell tickets) and make sure that all the tasks of preparation are spread evenly and yet done well so that no one will be too unhappy or so that everyone can be equally happy on that happy day. The amount of time energy, volunteer labour required to produce a parish dance or lawn fete or a booster club monthly 'meeting' is considerable and the return on this investment is carefully measured by everyone in terms of the number of people who come and how good a time they have.

In fact, this calculation is as aesthetic as it is economic. Since the highest goal is happiness for the greatest number and not profit, anything that will contribute to keeping the cost of tickets low and the price of drinks down is a plus. Big summer events under a tent when the dozen best bands agree to donate their services or play for small fees are the high point of the season, pointed to with pride by everyone, because so many come and paid so little for so much joy. This same value or evaluation is applied to all polka events.

A great many other values are linked to this ideal and are explicit or implicit in the many features of a polka fest that make it such a joy. For brevity's sake we'll list some of these features.

- All ages participate.

- Everyone dances.

- Though the spinning and stomping can become very intense and though the floor is full, people rarely bump into-each other.

- Coupling is not at a premium.

- A new partner for every dance is the ideal.

- Women dance with women a lot.

- Some of the best musicians are also some of the best dancers; all the younger musicians enjoy dancing.

- Many musicians can play two or three different instruments and a few can play all the instruments in the band.

- All musicians hold jobs in addition to their polka work.

- Songs for the band repertoire are often suggested by fans and in most bands all members contribute to the composing and arranging process.

- All bands have an 'English book' with a mix of popular hits that emphasises 'country & western' or 'English' or '50s rock' or 'Glen Miller songs', depending on the band.

- Bands try to answer every request.

- Almost every song is dedicated to someone or to whole families or 'tables', going out either from the band or from one participant to another via the band.

- Sexual teasing and joking and open flirting at polka dances have a 'fun for the whole family' feeling.

- There is wide tolerance for different styles of clothing, hair, demeanour.

- Individual dancing styles and styles that pairs of people develop are very much appreciated.

- Birthdays are always announced by the band and the song is sung. Anniversaries, weddings, engagements are noted. No one's life cycle is neglected.

- Musicians are not stars or sex symbols but are expected to be 'regular', part of the crowd, and to play until they are exhausted.

- Dancers are expected to dance to exhaustion.

- Everyone should drink a lot (eat some too) to get silly or happy, but not to get drunk.

- There should be no fights.

- Did everybody have a good time?

A Perspective on 'High Culture'

Art? We don't need it.

What we have been calling the 'arts' can be divided into four phase/kinds (not degrees):

- pre-arts or genuine cultural expression (made by most people in most times and places)

- art (from the renaissance to World War I in the West)

- aesthetics or anti-art (from World War I to the present)

- post-aesthetic expression, whatever that is

I think we can now see that art was an aberration and wrong. At its very rare best it substituted for a revolution, perhaps; at its next best it served as an opiate for the elites, the intellectuals, a balm to the bourgeoisie. Most of the time it simply exemplified commodity fetishism in its purest and most obscene forms.

The study of the distancing and substituting that art does is called aesthetics; if art is evil aesthetics is the banality of evil. The energy with which 'artists', intellectuals and teachers have aestheticised and anaesthetised experience for us the past fifty years or so may be directly proportional to the felt loss of art. In any case, people have been looking for beauty more frantically and finding it in less likely places - in trash, in the ugly, in silence, among 'primitive' peoples, etc.  The movements, labels, statements, keep accumulating - pop, op, bop, slop, camp, vamp - and accelerating, but the syrup of nostalgia that sticks to the latest creations moments after their arrival suggest that we are living in a museum at last, a hall of fame and mirrors in which everything is illusion or art. Until we have genuine cultures and classless societies again all of us who would be essential-izers, experience-intensifiers, worldview-manifesters, ontological-energy-tappers, must remain entertainers and/or aestheticians.

The movements, labels, statements, keep accumulating - pop, op, bop, slop, camp, vamp - and accelerating, but the syrup of nostalgia that sticks to the latest creations moments after their arrival suggest that we are living in a museum at last, a hall of fame and mirrors in which everything is illusion or art. Until we have genuine cultures and classless societies again all of us who would be essential-izers, experience-intensifiers, worldview-manifesters, ontological-energy-tappers, must remain entertainers and/or aestheticians.

It is almost as if music, assumed by many to be the cultural quintessence, the tip of the superstructural pyramid, offers the clearest demonstration of Marxist theory. Clearly the growth of the symphony orchestra and its music reflects perfectly the requirements of ruling class ideology; clearly the orchestra becomes a complete paradigm of fascism (E Canetti, Crowds and Power); just as clearly ruling class hegemony in music collapses entirely and internationally after World War I (Charles Ives quits, Anton Weber slides into serialism, Stravinsky goes from neo- this to neo- that, etc) and clearest of all, during and after the collapse only the working class is capable of creating new and genuine songstyles.

A Perspective from a Classless Society

A year and a half's work with the Tiv of central Nigeria, taught us:

- There are no words/concepts for art, beauty, music, aesthetics in Tiv.

- Everyone dances; any man or woman may compose songs.

- Quite a few composers are recognisable by the Tiv on the basis of melodic line alone.

- Every song style, every song, is built upon a specific motion, usually a dance or work pattern.

- Songs are not linked to specific emotions.

- Songs don't symbolise much of anything, they are not even 'unconsummated symbolism' in Suzanne Langer's sense, they simply and very forcefully are.

- The basic criteria for evaluating a song are almost entirely technical - is it detailed, clear, bright, complete, perfect? (Ironically, we would take this as evidence of a developed art-for-art's sake aesthetic).

- Song is a force, tapping into energies created by social frictions and causing frictions too.

Not so long ago, this planet was peopled with a variety of classless, artless, unscientific and relatively ahistorical-apolitical societies whose cultures were genuine. If Homo Sapiens is to continue here it will be in a diversity of ways once again, with this difference, that the road 'back' is likely to be filled with enough horrors that the survivors will be immunised against the worst forms of industrial civilisation forever after. The most material of material conditions, geological time, will dictate this proliferation of classless societies and genuine cultures eventually if a host of other less natural forces do not come to bear first. The sooner we persuade, enculture and politicise ourselves in these directions, the better the ecological bases will be for playing out any future options.

These perspectives 'on high culture' and 'from a classless society' are, of course, very cryptic and need further development, but they are meant to bracket and highlight and raise questions about the essential characteristics of people's music in this century.

About ten years ago, when we first tried to generalise about our various studies in urban music, we took as a working hypothesis a statement from Kenneth Burke:

Aesthetical values are intermingled with ethical values and the ethical is the basis of the practical ... Probably for this reason even the most practical of revolutions will generally be found to have manifested itself first in the aesthetic sphere.

'Following Burke' we wrote, 'one looks to musical styles for prophetic form, the delineation of an ethos, lyrical predictions of future politics. Yet the urban styles we have studied seem reactionary in their essential features, looking to the past for inspiration and finding it. Each style exists as a counter-force to rapid cultural change rather than a stimulant. Each provides a mirrored or reversed image of its social context. We would like to think that these styles have been moving backward into a future that is still waiting to be born, that the formal demands of blues, laika, and juju will be met eventually by societies that are equally clear, simple, and inspiring.'

This is an idealist vision and version of urban music if there ever was one. The kernels of truth within the 'aesthetics predicts politics' interpretation of these styles are much better expressed by the concepts proposed in Raymond Williams' article from which the opening citations are drawn.

It is astonishing but true that the musical styles of the contemporary working class are thousands of years old. The melodic 'modes' or 'dromi' (lit. 'roads') of Marcos Vamvakaris' songs in the 1930s lead back through Byzantium through the Arabic world to a time in pre-Homeric ancient Greece when these modes were associated with particular tribes - the Phrygians, Dorians, etc. The primordial qualities of the blues represent a common denominator of ageless African traditions. Yoruba juju style continues to reincorporate the traditional drum 'families' in the most recent records I've heard; an amplified 'mother talking drum' (iya ilyu) has replaced the electric bass! The polka fests of Buffalo, NY are probably as old as the Slavonic languages in their essential processes.

Henri Lefebvre, Everyday Life in the Modern World, (1968), talks about bringing back 'the festival', but in some key sectors of the working class the festival has never been lost. The basic process and practices that have kept 'the festival' - the collective-song-and-dance-and-food-and-drink - alive and well all over the planet despite the dominant culture are the same practices and processes that will one day enable us to overthrow the dominant culture and its class once and for all. If the coming revolution is to be worth struggling for, we must recognise that the social processes that support a polka party and a revolutionary party have a lot in common.

Charles and Angela Keil

Article MT081

(Note: portions of this paper were delivered at the MARHO Conference by Angela Keil; other parts have been pieced together from a paper delivered to the IPS Conference a few years ago and a Sunday supplement piece on Buffalo polka bands by Charlie Keil.)

In each of these styles, class factors (especially the relative importance of lumpen life styles and values) and various ethnic traditions blend differently, but each synthesis has the power to evoke strong responses across class lines and ethnic lines so that the effort to commodify those styles is usually unrelenting soon after their birth.

In each of these styles, class factors (especially the relative importance of lumpen life styles and values) and various ethnic traditions blend differently, but each synthesis has the power to evoke strong responses across class lines and ethnic lines so that the effort to commodify those styles is usually unrelenting soon after their birth.

And again, forty years of stylistic evolution has taken place before the music achieves wide popularity throughout Greece and some acceptance outside as well. From the hashish dens, jails, brothels, and army barracks of Piraeus and Athens comes the Zembekiko, the fundamental dance meter of laika style, slow, measured, stately, eighteen very carefully accented eighth notes to the bar. The bouzouki players are always in perfect unison, the singing is precise, the dancing a precious balancing of the bodily scales. The total effect is Apollonian in the extreme.

And again, forty years of stylistic evolution has taken place before the music achieves wide popularity throughout Greece and some acceptance outside as well. From the hashish dens, jails, brothels, and army barracks of Piraeus and Athens comes the Zembekiko, the fundamental dance meter of laika style, slow, measured, stately, eighteen very carefully accented eighth notes to the bar. The bouzouki players are always in perfect unison, the singing is precise, the dancing a precious balancing of the bodily scales. The total effect is Apollonian in the extreme.

by introducing amplification and provided the model for many Buffalo bands in the 1950s. But by then Li'l Wally Jagiello from Chicago was knocking at Buffalo's door.

by introducing amplification and provided the model for many Buffalo bands in the 1950s. But by then Li'l Wally Jagiello from Chicago was knocking at Buffalo's door.

has proven itself dynamically responsive to the changing tastes and needs of Polish-American communities across the nation.

has proven itself dynamically responsive to the changing tastes and needs of Polish-American communities across the nation.

The movements, labels, statements, keep accumulating - pop, op, bop, slop, camp, vamp - and accelerating, but the syrup of nostalgia that sticks to the latest creations moments after their arrival suggest that we are living in a museum at last, a hall of fame and mirrors in which everything is illusion or art. Until we have genuine cultures and classless societies again all of us who would be essential-izers, experience-intensifiers, worldview-manifesters, ontological-energy-tappers, must remain entertainers and/or aestheticians.

The movements, labels, statements, keep accumulating - pop, op, bop, slop, camp, vamp - and accelerating, but the syrup of nostalgia that sticks to the latest creations moments after their arrival suggest that we are living in a museum at last, a hall of fame and mirrors in which everything is illusion or art. Until we have genuine cultures and classless societies again all of us who would be essential-izers, experience-intensifiers, worldview-manifesters, ontological-energy-tappers, must remain entertainers and/or aestheticians.