all photos by Rod Stradling

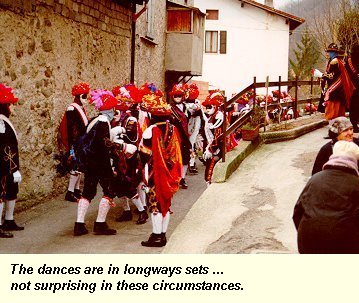

They dance all day on the Monday and Tuesday and perform in the streets, pubs and bars and the gardens or houses (photo right) of notables and former dancers and musicians. They have a men's side of as many as forty dancers and a kids' side of twenty or so. Almost all of the dances are in long sets. The music is provided by a band of fiddles, guitars and 'bassetto' (3-string bass).

In 1993 we noticed that most of the proceedings were being recorded by Aurelio Citelli - singer with Milanese folk band Barabàn. Later that summer, when we met Beppe Greppi who runs the Robi Droli record company, we found that they had produced a CD of the results, and that he was distributing it. A brief review is available.

The music and dance tradition in the Caffaro Valley is remarkable for its stylistic authenticity, richness and evenness of repertory, and is one of the most interesting of the many fiddle traditions which were once widespread all over northern Italy. That it is still alive and flourishing is mainly due to its being closely linked to the rite of Carnevale.

The Masked (i màscher) - On Shrove Tuesday, beside the smart ritual role of the official Compagnia, the unbridled and riotous carnival of 'The Masked', (rich in symbolic meanings, often openly erotic), trails through the streets. Boys and girls, men and women, are disguised in old traditional clothes, often of the opposite sex to the wearer. Their faces are hidden by grotesque masks and their voices are altered. They portray scenes of country life and play unsophisticated jokes - usually involving sexual innuendo and large quantities of confetti or onion skins - mainly on un-masked passers-by. This aspect of the carnevale is much more prevalent in Bagolino, where virtually the entire local population, and a good proportion of the visitors, are màschere.

The dance is structured on pairs of dancers who remain together throughout the carnevale. One of the pair takes the role of the 'chief' (capa) - the livelier of the two - and the other the 'figure' (figura). The capa e figura represent the male and female roles. This pairing is centrally important to the stylistic integrity of the dances and the ritual - indeed, some pairs have worked together throughout their dancing lives. (photo left)

The dance is structured on pairs of dancers who remain together throughout the carnevale. One of the pair takes the role of the 'chief' (capa) - the livelier of the two - and the other the 'figure' (figura). The capa e figura represent the male and female roles. This pairing is centrally important to the stylistic integrity of the dances and the ritual - indeed, some pairs have worked together throughout their dancing lives. (photo left)

The dance figures are a series of interacting quadrilles in longways sets; within each pair, the capa may dance with his respective figura, or with another capa. There are less frequent figures: the broad circle of Ariòsa, the ancient line procession (still found in three dances - Bal de Iusegn, Pas en amùr, Partenza Manöèl) - and finally, the chain (Cadina), used only in the dance of that name. Up to the '20s in some dances, instead of holding hands they used a handkerchief to join the pairs. The step is the rant, with variations, sometimes interspersed with the less frequent running step.

The hat is the most striking element; made of felt, covered by ruffled ribbons of red worsted, onto which are sewn the gold and jewels of the village, sometimes intermixed with mirror chips. On the left side of the hat a big multicoloured garland made of silk ribbon is fixed; its rhythmic movement during the dance is accentuated by the dancer shaking his head.

Their faces are concealed by whole-face masks which serve to impersonalise and disguise the dancers. Still handmade by many of them today, the masks are made of cloth stiffened with plaster, lined with wax to make them flexible, and painted ivory white with a black domino eye-mask (bautta) and red lips - sometimes the cheeks are reddened, particularly for the 'female' figura.

In the past, the masks were generally expressionless, though many of those in use today do have a definite expression and character. (photo left)

In the past, the masks were generally expressionless, though many of those in use today do have a definite expression and character. (photo left)

It's fascinating to see how many of the best dancers have developed a 'dance character', with an entire body-language which is perfectly suited to the expression on their mask. They move and hold themselves in a completely different way when you meet them out of costume at the various social events in the evenings.

One of the dancers, Gaetano Salvini, is an expert woodcarver and has made himself a most striking mask carved from a single piece of solid fruit-wood. Little more than 3mm thick in places, it is a thing of almost unnatural beauty. (photo right)

Gaetano is unusual in that, although dancing the figura role, he is the more lively of the pair and has developed a markedly feisty dance character which is completely at odds with the rugged calm of the man himself.

The Chief Dancer - The dancers are led by 'The Chief' (Il Capo) who manages and arranges the ritual and establishes the route, based on who in the community is prepared to pay for dances, to be performed at his home, bar, café‚ etc. He orders the musicians to perform the dances requested, arranges the dancers, prompts any changes in the figures by shouting precise orders. He is dressed like the dancers but unmasked, with one single ribbon to liven up his hat, and blows a small brass horn with which he gathers the dancers before starting every dance. He carries a shoulder-bag which he fills with the fees, gathered from the clients at the end of each stop.

Once, Il Capo was a real contractor - he organised the Fellowship at his own expense, engaged the musicians (trying to pinch the best ones from the rival Fellowship) and he ran the economic risk of the eventual success of the carnevale. At that time every dance was paid by the client at a fixed price; the more dances were requested, the greater was the fee. Nowadays there is a flat fee, so the money collected usually covers only part of the organising expenses - any short-fall is made up by a contribution from the dancers. Only the musicians get paid - their fee being related to the number of dances they played for - which tends to keep the event moving. You rarely find them stuck in a pub!

The Fool - The role of the Fool (il paiàso - derived from Pagliaccio), traditional up to the '60s, dressed in rags and with a broom, capering at the Capo's side, has been recently reintroduced by Ponte Caffaro's Fellowship. He is a kind of clown, performed by a skilled dancer with sense of humour. Though not taking direct part in the dance, he helped to arrange it, keeping the dancers in good order and safeguarding their dancing area. He will be seen to be an almost exact parallel to the Morris Fool.

The Zouaves - Up to the 1920s, some Zouaves were still active, though they no longer figure in the carnevale. They were dancers wearing different costumes; the capa wore a soft jacket with puffed sleeves, a high band laced at the waist, colour striped knickerbockers, the figura wore a knee-length white dress embroidered with open-work and bi-coloured stockings. They also wore the same masks used today and they had jingles pinned on their clothes and hats covered with multicoloured silk flowers.

The Children - In addition to the main Compagnia, there is also a boys' and girls' team; they belong to their own Fellowship, founded in the last decade, and coached by several of the adult dancers. They dance only on Sunday and on Tuesday afternoon, to music provided by the adult band, and they are a continual source of new dancers who, at the age of 14, if male, can join the official Fellowship. They wear the basic male and female 19th century country costume of the area, as used by the màschere in the carnevale, but without the grotesque masks.

Most of these children are quite young, yet some already show a marked aptitude for the dance. One little boy of around ten years of age was absolutely stunning in '94, and will make a wonderful contribution to the adult side when his time comes. On a sadder note - a pair of girls, aged around thirteen, one of whom was dressed as a male, gave a tremendously impressive display of skill and commitment throughout the carnevale that year and, as an acknowledgement of their prowess, were invited to join the adult dancers in the last few dances before the final Ariòsa. It was poignant to realise that, because of their sex, they would never be able to join the Fellowship, and that in one or two years, they would have to give up the dance for good.

On Monday, the action is centred in the farmsteads of the surrounding countryside, on Tuesday along the village main street. The ritual is over on Shrove Tuesday evening with the playing of the Ariòsa, in which members of the children's Fellowship, of both sexes take part.

The Caffaro Valley fiddle tradition dates back to that time; its source is to be found in the instrumental dance music in the 16th century, when the fiddle prevailed as the lead instrument and established a technique developing into the oral tradition, following a route which was technically and culturally quite different from the so-called 'seconda prattica' - from which the cultured style of the violin would evolve.

The instrument used today is the modern violin, with steel strings tuned to concert pitch (except in special circumstances noted below). The local handmade fiddles are still appreciated, though, obviously, standardisation and trade has brought mass-produced instruments of both higher and lower quality into the valley for the last century or so.

The bow used is also modern, set with the hairs very tight. Older players used to hold the bow at some distance from the frog, effectively shortening the bow length, but modern practice tends towards the orthodox grip. The bow strokes are short, detached and rhythmic, often one per note.

The Fiddle Tradition - The fiddle style is traceable back to the origins of violin practice, and is quite different from the modern 'classical' one. The instrument is usually held in the normal neck position, but is not gripped there as in classical practice. Shoulder rests are not used at all, as the mostly single position playing allows the fiddle to be easily supported by the left hand. Some of the oldest players remember fiddlers who held their instruments to their chests, with the corresponding steeply angled playing position and low bow arm. This was a technique adopted by many English country fiddlers.

It is certain that the ritual function of the carnevale, and its close cultural connections with the local people, has allowed the instrumental tradition to survive and maintain its special character up to the present time. Actually, it can be said to be a real 'school' of playing, with precise and original stylistic rules developed by generations of players, which - whilst leaving room for individual expression - are still quite strictly adhered to today. In the Caffaro Valley, the fiddle is considered the instrument 'par excellence'; irreplaceable in the carnevale repertory, and greatly appreciated even in the more recent liscio ballroom dancing tradition. In other parts of Italy the clarinet, accordion and others have replaced the more archaic instruments, but here the fiddle primacy has never been threatened.

Today, there are around fifteen fiddlers in Bagolino/Ponte Caffaro and their activity is limited mainly to the carnevale music - though this repertoire of thirty tunes finds other social uses in the community throughout the year. Up to about fifty years ago the musical environment was livelier than it is today, and although the musicians were not real professionals, they were people of considerable prestige; sought-after, well paid and well nourished. There were whole families of musicians, playing different instruments; often even the women played the bassetto or guitar, though never the fiddle. Musical literacy was very rare and all of the repertoire was learned and played by ear.

They met in kitchens through the whole year, particularly in winter time, and performed at special social occasions like weddings, serenades, fancy-dress and 'festi dei conscritti' (parties held as a send-off for young men about to leave for their two-year stint of National Service). At Christmas time and after, when the carnevale air started infecting everyone, there were increased opportunities to play at houses, bars etc., especially on Mondays and Tuesdays. Usually the music ceased during Lent; only on Ash Wednesday and the Half-Lent Thursday were the carnevale tunes heard again.

Towards the end of the last century in Bagolino (as in much of the rest of the country), a brass band was formed to play the music for the liscio craze then sweeping the country. In the wake of this, the new ballroom repertory began spreading among the few players who could read music. Many players maintained the old carnevale music and style, while others were able to learn, and in some cases reinterpret, the new dance tunes. The latter brought to the tradition some elements which were unknown up to that time, but which were required for the new repertory; the vibrato, glissando and a free use of several positions on the fingerboard.

The Apprenticeship - Once, the trainee fiddler learnt his art within the family; having heard the music from birth and - after carefully listening to father, elder brother, uncle - practising on their instruments. There was rarely much of a teacher/pupil relationship, rather a willingness to emulate, to learn, to be successful - and to reap the considerable rewards. Those who didn't belong to a musical family had to hang about the pubs and kitchens where fiddlers used to meet, and then try to keep the tunes in their heads long enough to get to a borrowed fiddle. This must have been very difficult, because all the tunes have two or even three 'voices', and someone playing the music alone was almost unheard of.

Anyway, somehow or other the beginner would learn some of the simpler tunes, usually in 'primero voce' and then during the year he would rehearse them with the other players. If he showed sufficient skill and the right attitude, he might get to perform some of them at the next Carnevale. The young fiddler had to gain himself a good reputation - and the ultimate acknowledgement of his merit would be his engagement by the Compagnia Sonadùr as a regular player.

Anyway, somehow or other the beginner would learn some of the simpler tunes, usually in 'primero voce' and then during the year he would rehearse them with the other players. If he showed sufficient skill and the right attitude, he might get to perform some of them at the next Carnevale. The young fiddler had to gain himself a good reputation - and the ultimate acknowledgement of his merit would be his engagement by the Compagnia Sonadùr as a regular player.

Admitting the youth to the Fellowship, the veterans played the 'secondo voce' counter melody, leaving the tune to the less experienced players. They would advise him to focus on his role, keep an eye on the dancers and engage his playing strictly with the shape of the dance - for to play the tunes with the right spirit is vital in a situation where the performance lasts for around 22 hours over two days. Everyone involved needs total commitment to maintain the level of performance over such a long period.

Today, one notices that it is the veteran fiddler, Andreino Bordiga, (photo above) who watches the dancers most; the rest of the band tend to watch him, and each other.

As the player absorbed the stylistic rules and gradually improved his technique, he could bring in variations borrowed from other fiddlers, or even devise his own. Many of the musical families developed their own 'house style' over generations. The most able players had no trouble performing with players from different stylistic 'schools', but some others had a hard time accommodating. So, at carnevale time, the Fellowship would sometimes engage whole families to guarantee a stylistic integrity for the music.

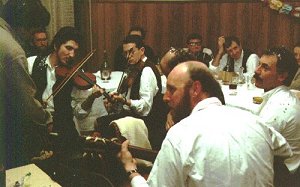

The traditional band once comprised only two fiddles, a bassetto and a guitar - this was solely for economic reasons. A player could earn in one day the equivalent of a week's wages, so the dancers - who paid for the music - curtailed their expenses by limiting the number of musicians. Nowadays the economic side is less relevant, so the band typically numbers from six to ten; three or four fiddles, one or two bassetti and between two and four guitars. (photo right) Solo performance is unknown in the Ponte Caffaro tradition.

The traditional band once comprised only two fiddles, a bassetto and a guitar - this was solely for economic reasons. A player could earn in one day the equivalent of a week's wages, so the dancers - who paid for the music - curtailed their expenses by limiting the number of musicians. Nowadays the economic side is less relevant, so the band typically numbers from six to ten; three or four fiddles, one or two bassetti and between two and four guitars. (photo right) Solo performance is unknown in the Ponte Caffaro tradition.

All the tunes are arranged in three parts (voci); the two high parts being taken by the fiddles, essentially playing a tune and counter melody, the low rhythmic third by the bassetto, reinforced by the guitar. Where there are only two fiddles, the left hand remains in first position at all times. If a third is available, it may either double one of the main melodies, or shadow phrases of, or sometimes the whole of, the secondo voce in the higher octave. In capable hands, the third fiddle can also develop a whole new part, both supporting the first and substituting the second. A forth fiddle will double the first in unison.

The musicians wear the wooden-soled clogs of the carnevale, and the traditional fustian male outfit of the valley (black, green or brown styled jacket and britches with gaiters) sometimes enriched by a shawl and coloured cuffs, and usually a hat and cloak against the bitter cold.

The String Bass - Most of the present-day Ponte Caffaro basses have been made in the valley. They differ as regards size, age, construction and quality, and most of them are bassetti - between 'cello and double bass in size. Some of them exhibit archaic design and constructional features linking them firmly with 17th century violin making practice; shorter string length, squat necks fitted (often with reinforcing nails or bolts) at right-angles to the body with a wedge to angle the fingerboard, strutting details, etc.

All of them have three gut strings, nominally tuned G-A-D - an eminently practical arrangement, since many of the required parts can be played without fingered notes at all; usually only two or three (exceptionally four) fingered notes are required.

The bass is always played with a handmade bow, both shorter and heavier than its classical counterpart. It is particularly suited to the short staccato bowings which give the music its rhythmic drive. The pizzicato is completely foreign to the traditional style.

The Guitar - The 'chitarra' has always been used in the string band for supporting and emphasising the terzo voce of the bassetto. Today the standard six stringed modern instrument is used, but in the past the multi-stringed chitarra battente (literally 'struck guitar' - also known as the Italian Guitar), was employed, played without picks - its legacy has been the unique local back-up style. This uses continuous chords rather than the usual alternating bass/chord format, and is found nowhere else in northern Italy.

A few decades ago, some of these old instruments were still to be found in the Caffaro Valley. Today only two remain; the fine fifteen stringed chitarra battente owned by the Guitar Museum in Brescia, signed "Gio. Pietro Mora - Bagolino 1777", and a second, rougher, three-quarter size six string instrument, of unknown make, but probably contemporaneous, kept by a Ponte Caffaro family.

Stringed Instrument Making - The Caffaro Valley is proud of its tradition of stringed instrument making, which carries on to the present day. Families preserve large numbers of instruments dating back to the 19th century, and a few from earlier times. Some of the old bassetti are still in use, though mainly at indoor static sessions - they would not withstand the hurly-burly of Carnevale. My experience has been that, when old instruments are used, the whole band will tune down a tone to avoid damage from high string tension. The local instruments were built by village carpenters, or sometimes even by the players themselves (driven by passion or need); men with exceptional manual skills, using acoustic ideas developed and transmitted by local tradition.

Today in Ponte Caffaro, Claudio Orsi, a local craftsman, continues to make fiddles and bassetti as he has since the 1950s, thus keeping his family's and the locality's tradition alive.

Other Instruments - During the critical years of the '50s and '60s, when the whole tradition was at its lowest ebb, some other instruments joined the bands. The mandolin was used in both bands, and in Ponte Caffaro even a mouth organ appeared. In the 1973/75 recordings made by Roberto Leydi and Italo Sordi at Bagolino, one mandolin was still in use. The fiddlers considered the mandolin unsuitable to the carnevale repertoire, though it was highly successful in the liscio music, and was widely used in informal masquerades 'outside' the Fellowship, together with the mouth organ and friction drum.

The mouth organ spread in the last century and is still widely used. It has often acted as a channel for young musicians to learn the simpler of the carnevale tunes and the associated 'monfrine' music, before incurring the expense of a fiddle.

Although a sense or rivalry between Bagolino and Ponte Caffaro has always been strong, the relationship between the two Fellowships has often been close; based both on competition and also co-operation, with exchanges of dancers and musicians due to family, business and friendship ties.

At the start of the '70s in Ponte Caffaro, only sixteen dances remained in the performed repertoire; they were: ![]() Ariòsa, Bal francés, Bas de tach, Biondina, Bosolù, Franceschèta, Mascherina, Molèta, Monichèla (sound clip), Oibò, Pas en amùr, Róse e fióri, Salta 'n barca, Sefolòt, Spasacamì and Tonina. By the mid '70s, the critical years were seen to be passing and, partly due to an influx of interested people from within the folk music revival, the Fellowship began to look forward to the future.

Ariòsa, Bal francés, Bas de tach, Biondina, Bosolù, Franceschèta, Mascherina, Molèta, Monichèla (sound clip), Oibò, Pas en amùr, Róse e fióri, Salta 'n barca, Sefolòt, Spasacamì and Tonina. By the mid '70s, the critical years were seen to be passing and, partly due to an influx of interested people from within the folk music revival, the Fellowship began to look forward to the future.

Thanks to this new attitude, and to the good memory of some veteran players and dancers, five dances which had fallen out of use were reintroduced to the repertoire; they were: Bal de Iusegn, Landerina, Partenza Manöèl, Segnù and Zingarella. Their reinstatement was primarily the work of Marcello Buccio (1912-1978), fiddler with the Ponte Caffaro Fellowship up to 1977.

At the 1985 Carnevale, two more dances were restored: Bal de l'urs and Cadina, collected from Constante Cosi (1917-1988), a Bagolino fiddler who was a member of the Ponte Caffaro Fellowship in the '40s and '50s. Finally, in 1991, Fiorentina was restored, collected from Stefano Bordiga (born 1913) another Bagolino fiddler who was a member of the Ponte Caffaro Fellowship in the '40s and '50s.

The four monfrine dances complete the repertoire. They are danced at carnevale time, but outside the official Fellowship, at any appropriate social situation, by both sexes. They share the 12/8 time, bipartite form, rant step, rhythm and melodic structure of the other dances, but have no specific figures. Except for La bella inglesina (better known as La e Mi), they have come down without names. One - now known as either Monfrina de Ciù or Sol e Do, has always been played, but the other two, although remembered by the older fiddlers, had not been danced for years. They were first collected in 1977 and reintroduced in the early '80s, and called Monfrine de Marcèlo (Nos. 1 & 2) for Marcèlo Buccio who handed them down. The Scotis (schottische) was once a very popular dance form, and was reintroduced thanks to the veteran fiddler with the present band since 1955, Andreino Bordiga (born 1931). The Pastorela is the only instrumental Christmas piece still in use, and is played on the night of Christmas Eve.

The four monfrine dances complete the repertoire. They are danced at carnevale time, but outside the official Fellowship, at any appropriate social situation, by both sexes. They share the 12/8 time, bipartite form, rant step, rhythm and melodic structure of the other dances, but have no specific figures. Except for La bella inglesina (better known as La e Mi), they have come down without names. One - now known as either Monfrina de Ciù or Sol e Do, has always been played, but the other two, although remembered by the older fiddlers, had not been danced for years. They were first collected in 1977 and reintroduced in the early '80s, and called Monfrine de Marcèlo (Nos. 1 & 2) for Marcèlo Buccio who handed them down. The Scotis (schottische) was once a very popular dance form, and was reintroduced thanks to the veteran fiddler with the present band since 1955, Andreino Bordiga (born 1931). The Pastorela is the only instrumental Christmas piece still in use, and is played on the night of Christmas Eve.

Musical Structure - All the tunes in the repertoire except one are in a major key. ![]() The most used key is D (18 tunes), while two are in G and two more are in A. Only Bosolù (sound clip) is partially in a minor key - it modulates from D minor to F major, and in the second part to D major. All the other tunes modulate between two or more keys.

The most used key is D (18 tunes), while two are in G and two more are in A. Only Bosolù (sound clip) is partially in a minor key - it modulates from D minor to F major, and in the second part to D major. All the other tunes modulate between two or more keys.

The tunes have a fairly small compass; fifteen are played only using the E and A strings, a further eight require the D, while the G string is rarely used except as a drone. The terzo voce, of course, has a wider compass, but higher positions are only used for the first string. In some cases double stops are used for a drone effect, sometimes even with double fingering - particularly to produce chords in the final measure. Three and four note trills are often used to enliven the melody, as are both types of gracing. Glissandi and vibrato are used sparingly, and in the case of the latter, only the finger is moved, rather than the whole hand as in classical practice.

Almost all the tunes are in 12/8 time, except for Bosolù in 6/8, Bal de Iusegn with a 6/8 first part, and Pas en amùr and Partenza Manöèl with a 4/4 first and final part respectively.

There are seventeen two-part tunes, usually of the AA-BB structure, and seven three-part ones - four are AA-BB-C, three are AA-BB-CC. All the tunes end with a short dominant/root cadence, except Segnù which ends abruptly. Some had an initial cadence as an introduction - a short ascending or descending scale, which has now fallen out of use. The monfrine have an AA-BB structure in two major keys, while the Pastorela has four parts, structured A-B-C-D-C-D-C, the first three being slow and the forth in faster monfrina time, this being the typical structure of the Christmas 'pive' (bagpipe) music of Lombardy. The Scotis, a 19th century dance, has three parts in D-A-G major, and an AA-BB-A-CC structure typical of the liscio repertoire. It ends with an accelerando A part.

Marks of the musical development have been identified by Italian ethnomusicologists, using detailed analysis of various aspects of the repertoire. In the main, the names of the tune/dance combinations reveal only general information; The Rose, The Chain, The Cocoon are figures from sword dances. The Knife Grinder, The Chimney Sweep, The Washerwoman, recall well known pantomimic dances related to crafts, widely used in carnevale dances all over the Alps. Other titles suggest sources in 18th and 19th century folk songs; for example, the Biondina coming from the famous Venetian Biondina in gondoleta - one of the boat songs popular in the first half of the 18th century, and widely know abroad.

Several of the tunes share names, as well as detailed melodic or structural similarities with other Venetian instrumental 'arias'; for example an 'Aria delle Monicella' - Monichèla, a 'Zufolot's aria' - Sefolot, and a 'Spazzacamin' - Spasacamì. This is not surprising, given the geographical closeness and historical, economic, military and cultural links between eastern Lombardy and Venice. The influential Carnevale di Venezia must also have contributed. In this context, one can see a parallel between one of the no-longer used Ponte Caffaro dances, Bal di pögn, where dancers mimed the threatening of fists, with the famous 'fist fight' of the Venetian Carnival - banned in 1705 for public order reasons.

Further, in an 18th century Venetian water-colour of the carnival by G Grevembroch, one can see an identical mask to the one used in the Caffaro Valley today, and it is well documented that the masks used by the morris dance tradition in 18th century Venice were very similar. It could also be argued that the separation - typically ritual - between the carnevale tunes and the others could, because of its Venetian ceremonial connection, allow Biondina to enter the former category, while the local and ancient monfrine were always kept separated.

So, it is possible to construct some sort of picture of the development of this extraordinary musical corpus; a picture within which archaic structures like processional and circle dances have been conditioned by renaissance melodies, by a partly homogenous group of song tunes and by the influence of the wealthy Carnevale di Venezia. This latter influence facilitated the introduction of the great tradition of country dances with their countless variety of figures, together with the dramas, exchanges and intrigues of 16th and 17th century Venetian life which, even today, contribute to the wealthy sumptuousness of the Bagolino carnevale. Due to the changed social circumstances of the late 20th century, this grandiosity was bound to become more and more ritualised and enigmatic, fixed as it is in a tradition which has, in the recent past, become more cohesive in choreographic and musical terms.

Today, we can see and hear the latest phase in the development of an instrumental practice traceable from the first Brascian violin consorts - maybe those same sonadori di li violinj who take us back over 400 years to the documentary sources of a tradition whose vivacity we can still enjoy as we approach a new millennium.

Compagnia Sonadùr di Ponte Caffaro - 'Pas en amùr' : Associazione culturale Barabàn - ACB/CD05

La musica del carnevale di Bagolino - Documenti della cultura popolare, volume 4, Regione Lombardia, Albatros (VPA 8236 Stereo)

Carnival dances of Ponte Caffaro - i Sonadur del Carnevale e la Compagnia dei Balari, Ponte Caffaro 1985. Le registrazioni sono state effettuate in Ponte Caffaro in collaborazione con lo Studio Boomerang.

Video:

La danza degli ori - Italian State Television made a superb programme showing, in commendable detail, all aspects of the 1987 Ponte Caffaro Carnevale.

Books:

Leydi R / Pederiva C - Il balli del carnevale di Bagolino in Brescia e il suo territorio. Milano, 1976

Pelizzari L / Falconi B - Il carnevale di Ponte Caffaro, Folkgiornale #8/9. S.Daniele di Friuli, 1989

Rod Stradling

Article MT004