...At the end of the summer, when the hay and the harvest had been gathered in, Mr. Norris gave a 'Harvest Home" to the people he employed...The dancing was in the courtyard of the house, on the clean stone floor and a local fiddler supplied the music on his fiddle...At Christmas there was sometimes a dance in the kitchen. A story goes, that on one occasion when the room was very full, the little old fiddler was hoisted on to the dresser where a chair had been placed, to put him out of the way...As public houses became increasingly commercialised, specific rooms were given over to social dancing when the occasion demanded. In April 1848 Richard Heritage, landlord of The White Hart at Marsh Gibbon, Buckinghamshire, noted in his diary, 'Our ball in Clubroom. Dance all night. Sims Bicester fiddler', while at another public house in the same village on Boxing Day that same year there was a 'ball of dancing at the Greyhound'.2

Other dancing venues might include barns, as at Maids Moreton, Buckinghamshire, on Whit Monday 1865:

...About 7 o'clock however it grew finer, and the field was well filled with a company of dancers, etc. The large barn in the centre of the village was opened for dancing and Mr. Francis Watts and his son supplied music to the dancers...Watts senior and junior were obviously popular local performers. Nearly a decade later, at the club feast in Tingewick, Buckinghamshire:5

...After the band had ceased to parade the streets, dancing was entered into with great spirit in the various dancing rooms, conspicuous among those being one at the "Crown Inn," and other [sic] at the "White Hart," music at the latter being supplied by Mr. F. Watts, and at the former by his son, John Watts...The type of music being supplied is not specified in either of these accounts, but seven years later, again at Maids Moreton:6

...In a large barn very kindly lent for the purpose, a large number of young persons entered into the mazey dance, to the excellent music of Mr. F. Watt's [sic] large piano, into which he has recently had a larger variety of dance music introduced...And during the following year:7

...In the large barn kindly lent for the purpose by Mr. A.C. Rogers, Mr. Francis Watts, of the "Crown Inn," Buckingham, had a large company of merry dancers to his monster piano, and dancing to smaller instruments was carried on in the several inns...For the first two of these occasions Francis and John Watts may have played live on unspecified instruments, but by the early eighteen eighties, at least, the former had acquired a player piano, and followed the long-established tradition of hiring out to celebrations in the locality. Transportation may have caused some problems, but presumably were, as with the portable dancing booths, conveyed via horse and wagon. By 1887, at least, in addition to keeping The Crown public house in Nelson Street, Buckingham, Francis Watts was also a 'musical instrument dealer'.8

That dancing was simultaneously occurring in at least three venues in the small village of Maids Moreton in June 1882 indicates how popular a feature of social gatherings it remained. At the Whitsuntide club feast in Finmere, Oxfordshire, that same year, 'many were indulging themselves in the dance to the strains of violin and accordion' ![]() 10; while at nearby Twyford, Buckinghamshire, nine years earlier:

10; while at nearby Twyford, Buckinghamshire, nine years earlier:

Whit-Monday was a festive day...All the bands in the neighbourhood having been engaged, they [i.e. the local inhabitants] determined not to be done out of a dance, so a violin was obtained, and the player found his hands fully employed, and the dancing was kept up till dark.Bill Williams, a close friend of the fiddle player Stephen Baldwin (born 1873), of Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire, described how this type of situation might produce a more spontaneous, more ad hoc, style of dancing, in contrast to the formal set dances. Peter Kennedy asks whether there would be 'anybody in charge,' which I take to refer to a dance caller:11

...No, there wouldn't be nobody in charge...The...the fiddler 'e'd sit down in 'is chair and 'e'd play the fiddle, you know, and everybody'd be 'aving their...drink an'...listening for a time, an' then...soon as 'e start on uh...the dancing, see...up they was an'...'olding one another, and round and round and dancing about there...in the club room. Well, I've knowed 'em up there as you couldn't hardly get inside the club room at the Cross, where there...there were so many people go in there...of a night...Public taste and social fashion were shifting, and couple dances such as the waltz, polka, Veleta, and others, eventually supplanted the older forms performed in a set. In June 1912, Cecil Sharp was at Kelmscott House, Oxfordshire, overseeing displays of the various forms of dances he had collected. One account of the occasion noted how these had been:12

...very popular at village feasts up to 40 years ago. These were presented in the style in which they were originally performed in the olden days, and brought back to the minds of some of the older inhabitants pleasant recollections of their youthful days, when, as lads and lassies, they "tripped it lightly" on the village green. "Ah," remarked one old lady, "'Tis like ould times, and the tunes be the same too," and she hummed the familiar strain of "Up and down the middle," beating time with her foot...But the exuberant country set dances that had taken an hour or more to run their course were well and truly a thing of the past. Taking their place were short, sharp displays where choreographic skill would be judged formally, leading ultimately - under a system initiated by the English Folk Dance Society - to points, medals and certificates being awarded to those deemed worthy. Yet another form of rural working-class expression had succumbed to urban middle-class sensibilities.13

No 4: John Potter of Sutton, Oxfordshire

One of the best known and respected morris dance musicians in west Oxfordshire during the middle decades of the nineteenth century was John Potter, of Sutton, a village adjacent to Stanton Harcourt. He was renowned over a wide area for playing the instrumental combination of three-holed pipe and tabor drum.  Joseph Goodlake, a member of the Stanton Harcourt Morris set, who had danced to his playing, commented that Potter 'could almost make un speak'.

Joseph Goodlake, a member of the Stanton Harcourt Morris set, who had danced to his playing, commented that Potter 'could almost make un speak'. ![]() 14 He was also proficient on the fiddle, which he played in a variety of musical contexts, and these will be examined in greater detail in this piece.

14 He was also proficient on the fiddle, which he played in a variety of musical contexts, and these will be examined in greater detail in this piece.

His father, William Potter, was baptised in Charlbury, Oxfordshire, on 9 March 1793, although his parents, John and Jane, were evidently only temporary residents, as the register gives the note, 'belongg [sic] to Brighthampton', a dozen miles due south. When he married Elizabeth Foster of Stanton Harcourt on 29 January 1810, William was residing at nearby Northmoor, two miles south of that village. John Potter was their second child, baptised 12 September 1813, and on four occasions between that date and 1823, William is noted as 'labourer of Sutton'. The census of 1841 confirms his occupation as agricultural labourer, and his place of residence as Duck End (presumably Ducklington End), Sutton. The 1841 census listed only the occupation of the head of the household, so that John Potter's mode of employment at this date is not recorded. But he was still living with his father and sister Elizabeth.

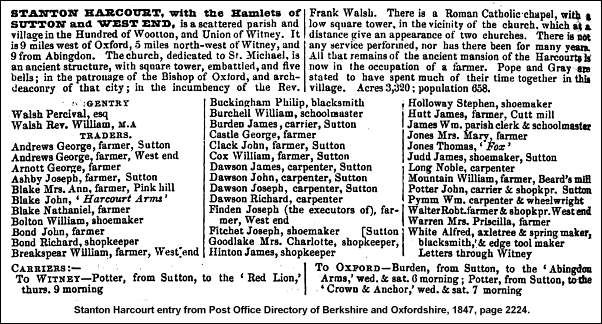

Four doors away (assuming the enumerator followed a logical perambulation through the village) lived the family of George and Charlotte Goodlake. His occupation was given as 'Grocer &c'. Joseph Goodlake, already noted as one of the Stanton Harcourt dancers, was one of their children, born 8 May 1836. Clearly there was a close relationship between the two families, and it seems likely that through this association Potter became a carrier and shopkeeper in his own right. George Goodlake had himself risen through the social ranks. At the baptism of seven children between 1820 and 1831 his occupation is given as labourer. By 1833, and again in 1835 and 1838, he is a baker. In both 1836 and 1840 he is described as shopkeeper. And at the baptism of his thirteenth, and final, child in 1842, a publican; while at the date of a daughter's wedding in 1844 he is noted as victualler. Following his death in 1846, his widow Charlotte maintained the shop until 1853, at least.

Although I have been unable to discover where and at what date Potter married Alice Mitchel, of Wytham, Berkshire, this would have taken place prior to September 1845, when their only child was baptised. In the register he is given as 'Carrier of Sutton'. Between that date and 1875, at least, he appeared regularly in published trades directories in his twin roles of shopkeeper and carrier. For much of this period his weekly schedule was consistent. On Wednesday and Saturday he would leave Sutton at seven in the morning to travel to a designated public house in the centre of Oxford City, returning around three thirty in the afternoon. The River Thames lay between and because the only convenient crossing was over the toll bridge at Swinford, the round trip was about twenty two miles. And at nine on Thursday mornings he would make the much shorter trip - about seven miles there and back - to another public house in Witney. At some point between 1867 and 1875 he had added a regular Monday journey to Abingdon, a total return trip (again avoiding the river) of just over twenty miles.

A carrier needed to run a reliable service, and if that was not maintained there was always a rival in Sutton to take up the slack. These journeys were, therefore, made in all weathers: sunshine, rain and snow. Speaking posthumously of his father-in-law in 1892, Maximillian Charles 'Maxey' Mitchell observed that he was 'always a strong man', but 'always suffered with the cold', ![]() 15 exacerbated, no doubt, by frequent seasonal travel in adverse weather conditions. Mitchell (himself a carrier and perhaps speaking from personal experience) added, 'When he was a carrier he used to drink', which is hardly surprising given that three, and later four days a week he had time to kill while waiting to make the journey home, and this would often be spent in the vicinity of a beer retailer.

15 exacerbated, no doubt, by frequent seasonal travel in adverse weather conditions. Mitchell (himself a carrier and perhaps speaking from personal experience) added, 'When he was a carrier he used to drink', which is hardly surprising given that three, and later four days a week he had time to kill while waiting to make the journey home, and this would often be spent in the vicinity of a beer retailer.

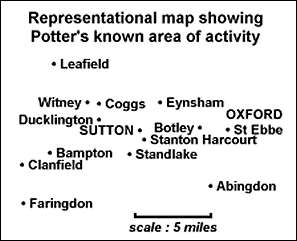

Although there is no evidence to indicate at what date Potter learned to play either pipe and tabor or fiddle, he may well have been active as musician to morris dance sets from as early as, say, the eighteen thirties. What is certain is that, over an extended timespan, he provided the accompaniment to at least ten separate teams. As 'Maxey' Mitchell related to Percy Manning's fieldworker Thomas Carter in 1894, Potter had (in Carter's eccentric written style) 'for a verry long time Played to all the Morrises for Many Miles Round'. Those named were sets at Stanton Harcourt, Standlake, Bampton, Witney, Eynsham, Coggs, Leafield ('Field Town'), Clanfield and Faringdon. Mitchell was apparently unable to give further specifics, but added that Potter had additionally played at, 'Many other Places & Sometimes into Oxford'. ![]() 16

16

To these we may add, at least, Ducklington. John Lanchbury from Ramsden was associated by one informant as the regular musician for the set of dancers named, but he added that 'Old Potter also played here at times'. ![]() 17 Given that, on occasion (and almost certainly during the eighteen fifties, at least), there were two or three distinct dance sets based in the village and out performing simultaneously, there was employment to be had by several musicians.

17 Given that, on occasion (and almost certainly during the eighteen fifties, at least), there were two or three distinct dance sets based in the village and out performing simultaneously, there was employment to be had by several musicians. ![]() 18

18

In a previous instalment in this series I suggested that Edward Butler may have acted as musician for the challenge match held about 1854 at The White Hart in Minster Lovell, at which morris sides from Standlake, Ducklington, Brizenorton, Bampton and Leafield competed for supremacy. ![]() 19 Equally as likely a candidate - perhaps more so, given that he is elsewhere confirmed as having played for four of the five teams - is Potter himself.

19 Equally as likely a candidate - perhaps more so, given that he is elsewhere confirmed as having played for four of the five teams - is Potter himself.

In his manuscript history of the morris tradition at Bampton, Oxfordshire, dated January 1914, William Nathan 'Jingy' Wells, himself a fiddle player, lists successive musicians who had played to the Bampton set from about 1840. This includes Potter, but implies that he was involved there for merely two or three years.

These details came to Wells via his uncles Henry Radband (born 1836) and James Portlock (circa 1839). Although Wells claimed in January 1914 that Radband had 'taken part 56 years',

Richard Ford Bampton Oxon about 1851 Old Mr. Potter (Stanton Harcourt) Oxon about 1856 [...] Robert Batts Bampton about 1858 20

The first newspaper report of the Whit Monday morris dancing at Bampton occurs in 1858, a date for which Wells has fiddle player Robert Batts as probable musician. In that account the correspondent rails against:

...the substitution of a squeaking fiddle for the appropriate, and to our mind, orthodox "tabor and pipe", which in our boyish days were so admirably played by the well and widely-known "poor old Master Beechey, of Lew."But for performance accompanied by the 'orthodox' music he needed to look no farther back in time than the previous year, when, implicitly, John Potter had been out perambulating the town with the dancers.23

In 1914 Wells explicitly identifies Potter as having been from Stanton Harcourt and places him in the list of pipe and tabor players. At a later date, however, his memories apparently became more confused. In a letter published in 1937 he mentions 'old Potter from Ducklington'. ![]() 24 Perhaps around the same date, but certainly prior to his death in 1953, he related some of the morris history to his friend W A D Morris, who subsequently committed a portion of it to print. Among those stories was one relating to Potter.

24 Perhaps around the same date, but certainly prior to his death in 1953, he related some of the morris history to his friend W A D Morris, who subsequently committed a portion of it to print. Among those stories was one relating to Potter.

...Me grandad told me that Ted Potter from Ducklington [sic] used to play the fiddle for the Morris. He also used to play the "Whit (whistle) and Dub." Today we call it "pipe and tabor"...In fact, there are no men named Ted Potter residing in Ducklington during the nineteenth century, and nowhere in his extensive manuscripts does Wells link any musician other than Potter with that village. The confusion may have originated with Potter's residence being at Duck End, suggested earlier as an abbreviation for 'Ducklington' End, that is, at the west end of Sutton. But from within the jumbled memory set another snippet emerged that probably also relates to Potter, and which adds an extra dimension to his musical activities. Writing of musicians active during the period of his grandfather's tenure as leader of the Bampton Morris (George Wells, died 1885), Wells commented in 1937:25

...At the time he died there was a man from Fieldtown & a man from Ducklington. The man from Ducklington used to play 4 instruments...Wells would almost certainly have thought of pipe and tabor as a single instrumental combination, while Potter is known to have also played the fiddle. What the remaining two instruments might have been, however, is unrecorded. There is a suggestion that Potter possessed tune books, which passed to Percy Manning via 'Maxey' Mitchell,26

There is one further connection with Bampton. The whittles, or three-holed pipes, used by Potter were, according to 'Maxey' Mitchell in 1894, 'made by [blank] Brooks who kept George + Dragon at Bampton about 80 years ago'. ![]() 28 This man may be identified as Robert Brooks, baptised in Bampton on 12 July 1789. At successive baptisms of children he is recorded as labourer (1814), barber (1818), hairdresser (1820, 1822 and 1824), and finally, in 1829, publican, confirming Mitchell's oral tradition. And one of these pipes found its way back to Bampton and into the hands of 'Jingy' Wells, and thence to Helen Kennedy.

28 This man may be identified as Robert Brooks, baptised in Bampton on 12 July 1789. At successive baptisms of children he is recorded as labourer (1814), barber (1818), hairdresser (1820, 1822 and 1824), and finally, in 1829, publican, confirming Mitchell's oral tradition. And one of these pipes found its way back to Bampton and into the hands of 'Jingy' Wells, and thence to Helen Kennedy. ![]() 29

29

Much of this recorded evidence for activity with various morris dance sets appears to relate to the period around the eighteen fifties. Within a decade of 1860 the custom had been abandoned in the vast majority of communities, and the opportunities for employment among musicians seriously curtailed. But if the disappearance of the morris tradition had effected a shift in lifestyle for Potter, especially during the Whitsuntide period, his circumstances were entirely transformed following the death of his wife in September 1878.

Between that date and 1880 John moved away from his home village to live in St. Ebbe, a densely populated area a little over a quarter of a mile square, in the heart of Oxford City. ![]() 30 A more dramatic change in living conditions, from the open countryside of the Thames Valley to closely-packed and gardenless terraces, can scarcely be imagined. His place of residence in 1880 was 31 Penson's Gardens.

30 A more dramatic change in living conditions, from the open countryside of the Thames Valley to closely-packed and gardenless terraces, can scarcely be imagined. His place of residence in 1880 was 31 Penson's Gardens. ![]() 31 It seems likely that his relocation had been facilitated by a friend already living in that parish. The most likely scenario involves the assistance of Thomas Goodlake, a son of George and Charlotte, brother of the Morris dancer Joseph, and (on no evidence whatsoever) possibly himself one of the dancers. As a youth he had been Potter's neighbour back in Sutton. Now aged 51, he was was a 'sugar boiler and confectioner' living at 21 St. Ebbe Street, having been resident in Oxford City for at least fourteen years.

31 It seems likely that his relocation had been facilitated by a friend already living in that parish. The most likely scenario involves the assistance of Thomas Goodlake, a son of George and Charlotte, brother of the Morris dancer Joseph, and (on no evidence whatsoever) possibly himself one of the dancers. As a youth he had been Potter's neighbour back in Sutton. Now aged 51, he was was a 'sugar boiler and confectioner' living at 21 St. Ebbe Street, having been resident in Oxford City for at least fourteen years.

When the national census was taken in early April of the following year, the house at 31 Penson's Gardens was occupied by the family of one William Potter, aged 36 and born in Reading, Berkshire, who just possibly was a relative. John Potter had moved three doors away to number 28, and was living in The Gardeners Arms public house.

At this date, Potter's mode of employment was given as carpenter. Perhaps significantly, in 1880 Augustus Rockall, carpenter and joiner, lived next door to Potter, at number 30. But more importantly for his musical inclinations was his proximity to the chimney sweep John Hathaway (then aged twenty four), a mere two hundred yards distant, at 45 Friars Wharf. Also within the same dense network of houses, just round the corner from Penson's Gardens, at 16 Bridge Street, lived Henry Taunt, father of noted photographer Henry W Taunt, who immortalised a number of traditional customs on film, including the morris dance teams at Chipping Campden and Bidford (both in 1896), and Headington Quarry in 1899. ![]() 32 The younger Taunt had himself been born in St. Ebbe, in 1842, and would have been well acquainted with the Hathaway family. By early April 1881 he lived at 9-10 Broad Street, less than half a mile distant, where as a successful businessman he employed eleven men, four women and seven boys in his photographic shop.

32 The younger Taunt had himself been born in St. Ebbe, in 1842, and would have been well acquainted with the Hathaway family. By early April 1881 he lived at 9-10 Broad Street, less than half a mile distant, where as a successful businessman he employed eleven men, four women and seven boys in his photographic shop.

Over the following decade, Potter followed the carpentry trade, and also played music in various of the public houses in the locality, of which there were more than two dozen within a few minutes walk from his home. ![]() 33 By 1884 he had moved out of St. Ebbe proper and was living a few hundred yards to the west, in the Lamb and Flag Yard, a set of dwellings around a courtyard at the rear of The Lamb and Flag public house, on the corner of High Street and Hollybush Road.

33 By 1884 he had moved out of St. Ebbe proper and was living a few hundred yards to the west, in the Lamb and Flag Yard, a set of dwellings around a courtyard at the rear of The Lamb and Flag public house, on the corner of High Street and Hollybush Road. ![]() 34

34

It was here that he resided when the Hathaway family of chimney sweeps decided to revive one of the old customs long associated with their trade. Roy Judge has analysed this connection of May Day with the sweeps in some depth, and in his published volume ![]() 35 details the increasingly elaborate costuming of the participants. One character which assumed a central role in the custom from the early years of the nineteenth century was that of 'Jack in the green', consisting of a man encased from head to ankle in foliage and spring flowers.

35 details the increasingly elaborate costuming of the participants. One character which assumed a central role in the custom from the early years of the nineteenth century was that of 'Jack in the green', consisting of a man encased from head to ankle in foliage and spring flowers.

In Oxford City the custom was reported as early as 1828, and sporadically to May Day, 1871, when a performance was forceably prevented by the police, on the charge that it was begging. As with all forms of exuberant working-class customary practise around this date, toleration and patronage from those higher up the social scale was rapidly being withdrawn. But this might not be the whole story. Several reasons mitigate against the recording of the 'Jack' custom in Oxford City, not the least being the claim to column inches in the three (and at times four) weekly newspapers by the restrained, formal and socially-acceptable performance of the choirboys from the top of Magdalen Tower at an early daylight hour on May Day morning. The second obvious reason is one of geography. A reporter may (or may not, of course) have been out on the streets on May Day, but it would be easy in a town the size of Oxford to simply miss the performance of the sweeps and their 'Jack'. In a similar manner, the correspondent from the much smaller town of Bampton wrote in 1862:

...We heard that there was a party of Morris dancers, but we were not favoured with a specimen of their evolutions, probably because we reside in so out-of-the-way a locality; we, therefore, cannot praise their performances, even if they deserved so much...In its report of May Day festivities in Oxford City, that same newspaper noted the presence of one or more 'Jack in the green' parties in both 1884 and 1885.36

...the ancient "Jack in the green" seems to have entirely lost his place amongst the customs of the day in the neighbourhood...The possibility of organisation of a 'Jack' party by one or more different groups in 1884 and 1885 in various parts of the City needs to be addressed. But the note of sightings in these two years may be nothing more than the Journal reporter recalling an earlier incarnation of the 'ancient and recognised custom' (as the 1871 account had it) and projecting a nostalgia-tinged wish fulfilment. Certainly both newspapers make a point of commenting that the party organised by the Hathaway family and taken onto the streets on May Day, 1886, was a revival following a lapse. Reports noted that it was 'a very old custom which has not been seen in Oxford for many years',38

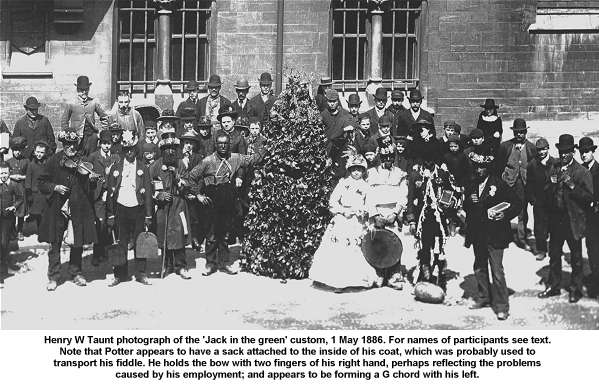

Henry W Taunt was ready with his camera in 1886 to record the appearance of the 'Jack', perhaps forewarned by intelligence from his father, who still lived close by the Hathaways. On May Day morning (on the evidence of the shadows cast perhaps about eleven o'clock) he evidently had them call at his shop at 9-10 Broad Street, to pose for their photograph, reproduced here.

...Bob Potter, the fiddler of Stanton Harcourt; A. Hathaway with shovel and poker; Tom Dane with money box; John Hathaway, Jnr., as Jack in the Green; Lewis Bensley, the lady with the ladle; Robert Bensley, the Lord of Misrule; H. Bensley, the Fool with the Bladder; and R. Hathaway with money box...This is convincing, if late, evidence of Potter's involvement, but at a much earlier date, in the manuscript of Percy Manning, there is circumstantial evidence to suggest that Potter had indeed been the fiddle player on this occasion. Adjacent to material collected from 'Maxey' Mitchell is the note, 'Taunt's photo taken 1886'.42

Evidently time and sensibility had been ripe for a revival of the 'Jack' ceremony, and the opportunity seized. The majority of customs require advance planning, a sufficient number of participants for enactment, suitable costuming and accessories if deemed appropriate, and a musician where required. All these factors fell into place during the early months of 1886, and while both the actual form taken by the custom and the circumstances surrounding its revival demand a more detailed analysis, a brief rehearsal seems appropriate.

The comment of the Oxford Times reporter in 1885, given above, is tinged with nostalgia and regret that the 'antient "Jack in the green"' no longer made an appearance. Hathaway family members may (or may not) have spotted this and taken it to heart. During the early months of 1886 the revival of the 'Ancient Morris Dance' at Bidford-on-Avon, Warwickshire, by D'Arcy Ferris was a widespread topic of interest throughout the south Midlands. Although none of the Oxford newspapers appear to have succumbed to Ferris' widespread publicity campaign, a cosmopolitan community such as Oxford would certainly have heard the stories of the successful and widely acclaimed tour across the Cotswolds by the Bidford men. ![]() 44

44

Sufficient personnel had by this date become available for a revival of the 'Jack' custom. The strong back needed to carry the heavy framework of foliage was found in John Hathaway, then aged twenty nine and physically active, as chimney sweep in 1881 and (taking over his father's trade) horse slaughterer ten years later. Members of the Bensley family, long resident in the City, assumed three of the roles. Robert Bensley (aged forty two in 1886, a bricklayer in 1891) acted as 'Lord of Misrule', an archaic term adopted in early 1886 by D'Arcy Ferris to describe his own role within the Bidford Morris revival, and one obviously mentally associated with Bensley by Fred Taphouse. The fool, 'H Bensley', may be identified as Robert's son Henry, then aged nineteen and a 'General Labourer' in 1891. Lewis Bensley, as yet unlocated in the official sources, is most likely to have been yet another of Robert's sons. Of the two money collectors A and R Hathaway, the former also remains unidentified, but the latter is almost certainly Richard (then aged twenty four and in 1881 a 'Labourer (Carter)', presumably working for his carrier father), a younger brother of John, the man inside the 'Jack'.

Of the paraphernalia required to field the custom, Henry W Taunt wrote of how the Hathaway family had taken:

...an amount of pains to build their "green" and dress their performers in orthodox fashion, [and] were very successful...[The 'Jack' was] made of wicker work covered with leaves and laurel with flowers in between...The remaining accoutrements were relatively common: shovel and poker (signifying the long-established association of May Day with the sweeps), a ladle, an inflated bladder (quite probably from one of the slaughtered horses which were the stock in trade of John Hathaway senior), and three collecting boxes, which appear to have been hand-crafted by an experienced carpenter.45

And, finally, John Potter, with his vast store of tunes and extensive experience of playing for dancing (not to mention his skill as a carpenter), was living almost on the doorstep.

Of their physical activity on the streets, Taunt described how:

...Jack-in-the-Green reeled round one way and the performers danced round it in reverse, clanging their poker and shovel and pot and ladle as they swung past, while the violin squeaked out a merry old English dance...The following May Day apparently saw no appearance of the 'Jack',46

...Other customs, both old and new, were also observed, there being a Jack-in-the-Green and children carrying garlands, the main purpose of those engaged in both being the solicitation of money from the general public. The first named was conducted by the members of a well-known family of chimney sweeps hailing from the Friars [i.e. St. Ebbe], and the "company" included an ancient-looking fiddler, a boy wearing a collegian's cap and carrying a sweep's brush and shovel, a gaudily-dressed female, and two or three men, whose principal ornament in their odd attire was bright-coloured ribbons, and who capered about around the man in green to the strains of the fiddle. Two of them with moneyboxes in their hands went hither and thither gathering halfpence, and apparently the party did not do a bad day's work...The following year, 1889, the custom was conspicuous by its absence,48

Eight weeks before May Day of the following year he was dead. The circumstances surrounding Potter's final hours on earth were given at a coroner's inquest, held on 11 March 1892.

...James Holloway, 4, Nelson-yard, St. Aldate's, labourer, said he had known deceased for some time. On Tuesday [8 March] witness was in Mr. Ward's wharf, Park End-street, about half-past five, and saw deceased. Witness told him the wharf was about to be closed for the night, and he made no answer. Witness went to the foreman, and said he thought deceased was ill. The foreman came and tried to get him up, but found he could not stand. He was sitting on a box where he had been working. Deceased was afterwards put on to a trolley and taken home. He did not speak, but seemed sensible. On arriving at the house the deceased took a key from his pocket, unlocked the door, and went in. Witness asked if they should help him upstairs, but he refused their assistance,and [sic] said he should be better tomorrow. As witness left, the deceased shut the door, and he heard him lock it...'Maxey' Mitchell gave evidence of how he came to find the body of his father-in-law two days later, incidentally revealing several otherwise unrecorded facets of Potter's life and character.52

...Maximillian Charles Mitchell, carrier, Cumnor, said deceased was formerly a carrier, and was his father-in-law. He had done nothing regular of late. Witness had seen him frequently lately. He was always a strong man, and lived by himself. When he was a carrier he used to drink, but of late years he was temperate. He played at public-houses, and witness saw him on Saturday at the "Balloon," Queen Street. He left him at six o'clock. He was awkward in walking and clumsy with his hands, knocking them about while at work. He always suffered with the cold. On Thursday morning witness had a letter from H.J. Owen, the landlord of the house, to say that the deceased was brought home ill on Tuesday night by four men, and he had not been seen since. Witness went to the house the same morning about twelve o'clock, and knocked several times, but had no answer. He then borrowed an iron bar and opened the door. On going upstairs to his bed-room he found deceased lying partly on the bed quite dead. He was fully dressed with the exception of his shoes being off. There was a candle on the table in the room, but it had apparently not been lighted. He believed deceased died naturally. His shoes were close to him, and it appeared as if he was about to undress and get into bed...Additional observations included the fact that Potter's bedroom 'presented a most neglected appearance',53

Potter's 'awkward' mode of walking is likely to have been a result of half a lifetime of travelling in an open carrier's cart in all weathers, resulting perhaps in rheumatism or arthritis. His clumsiness with his hands would have additionally been exacerbated by years of carpentry work. And yet, even in the week prior to his death, he was still able to play the fiddle in various public houses, including The Balloon, a few hundred yards from his home.

Mitchell comments that he had seen Potter 'frequently lately.' In his role as carrier living in Botley, two miles to the west of Oxford City, he made the journey there and back daily, ![]() 56 and would thus have had ample opportunity to visit his father-in-law. Although he observes that Potter had done 'nothing much of late' in the way of work, on the day of his death he appears to have been employed at Mr. Ward's wharf on Fisher Row, beside the canal.

56 and would thus have had ample opportunity to visit his father-in-law. Although he observes that Potter had done 'nothing much of late' in the way of work, on the day of his death he appears to have been employed at Mr. Ward's wharf on Fisher Row, beside the canal.

Potter's importance to the social, commercial and cultural life of the area between Oxford City and the border with Gloucestershire to the west was extensive.  For more than three decades he travelled out and back from Sutton to Oxford and Witney three days a week (later adding a trip to Abingdon on Mondays), carrying goods and passengers to those market towns. His shop in Sutton itself sold provisions to keep body and soul together and would, in common with most country shops of the era, have acted as a focal point for meeting friends and exchanging gossip. We may observe, however, that his was a life more commercialised, more monetary-biased, and his status elevated far above his labouring peers. Even in times of widespread general dearth, such as occurred during the Crimea War of the middle eighteen fifties, he is unlikely to have wanted for at least the basics. And yet, although his various enterprises took him many thousands of miles, Potter's whole life appears to have been played out within a fifteen mile radius of his birthplace.

For more than three decades he travelled out and back from Sutton to Oxford and Witney three days a week (later adding a trip to Abingdon on Mondays), carrying goods and passengers to those market towns. His shop in Sutton itself sold provisions to keep body and soul together and would, in common with most country shops of the era, have acted as a focal point for meeting friends and exchanging gossip. We may observe, however, that his was a life more commercialised, more monetary-biased, and his status elevated far above his labouring peers. Even in times of widespread general dearth, such as occurred during the Crimea War of the middle eighteen fifties, he is unlikely to have wanted for at least the basics. And yet, although his various enterprises took him many thousands of miles, Potter's whole life appears to have been played out within a fifteen mile radius of his birthplace.

His musical talents were utilised by more than a dozen separate morris dance sets on numerous occasions, and he also provided music in various further contexts. His great skill on several musical instruments provided entertainment for untold thousands, even to within a few days of his death, during a career spanning perhaps six decades.

Keith Chandler - 23.11.00

Article MT066

name age occupation place of birth William POTTER 55 Agricultural Labourer John 25 Elizabeth 15

name age occupation place of birth John POTTER 39 Carrier Stanton Harcourt Alice [wife] 45 Wytham Anne [daughter] 5 Stanton Harcourt Edward SHEARD [serv] 15 Buckland

name age occupation place of birth John POTTER 48 Carrier Stanton Harcourt Alice [wife] 50 Wytham

name age occupation place of birth John POTTER 58 [Grocer] Stanton Harcourt Alice [wife] 66 Grocers [sic-wife] Berks, Wytham

name age occupation place of birth John TANNER 57 Publican Oxford Julia [wife] 59 At Sea Off Portsmouth John POTTER [lodger - widower] 68 Carpenter Stanton Harcourt

name age occupation place of birth John POTTER [widower] 77 Carpenter Stanton Harcourt

Note: The 1871 census entry for Potter is confusing, as it gives his occupation as 'do', generally meaning 'as above'. The previous entry is 'Agricultural labourer', but this is evidently an error, for Alice Potter is noted as 'Grocers', a convention used for females to indicate their status as a wife. So, the actual entry was clearly intended to record Potter's status as a grocer, a role confirmed by the trades directories.

By the time I began serious research in the area, in 1978, it was too late to uncover any significant information on John Potter. In 1981 the second wife of Jim Evans in Eynsham (his father played for the Eynsham Morris), who was a native of Stanton Harcourt, told me that she remembered her mother speaking of John Potter, but could recall no details. On 19 September 1986 I telephoned the only Potter still listed in the Phone Book for the area around Stanton Harcourt, but she and her husband were neither related to, or knew anything about John Potter. And on 15 February 1991 I rang the only Mitchell still listed for Cumnor, but this was no relation to 'Maxey' Mitchell.

With thanks to Malcolm Graham and his staff at The Centre for Oxfordshire Studies, Oxford Library, Westgate, Oxford; Roy Judge; Mike Heaney. Transcripts of Crown-copyright records in the Public Record Office appear by permission of the Controller of HM Stationary Office.

| Top of page | Articles | Home Page | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |