Article MT083

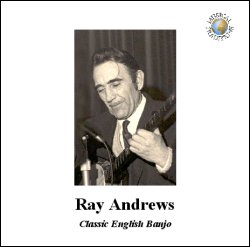

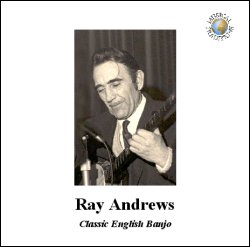

Ray Andrews

Classic English Banjo

Musical Traditions' fourth CD release of 2001: Ray Andrews: Classic English Banjo (MTCD314), is now available. See our Records page for details. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the record, or who might find the small print hard to read, we have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here. As usual, photo credits can be seen by hovering the cursor over the picture.

[Track List] [Introduction] [Part 1 - Ray's life] [Part 2 - English Classic Banjo Tradition] [Part 3 - banjo music in Britain and Bristol] [The Tunes] [Appendix] [Credits]

Tracklist:

- Shaeffer's Jig

- Entrancement

- Bluebells of Scotland

- The White Coons

- La Margeurite

- The Kilties

- Whistlin' Rufus

- Hurdy Gurdy Gallop

- Tune Tonic

- Grandfather's Clock

- Bonny Scotland

- Annie Laurie

- Banjo Vamp

- Hornpipe and Jig Medley

- Spanish Romance

- Sailors Don't Care

- Sports Parade

- Mr Punch

- Beat as You Go

- Kaffir Walkround

- Darktown Dandies

- Minuet in G

- Rugby Parade

- Oh Lonesome Me

- Niggertown

- Just a Song at Twilight

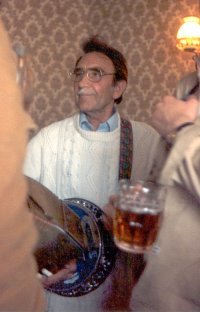

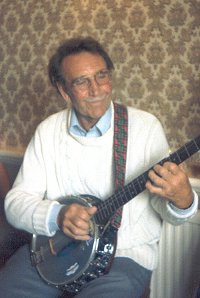

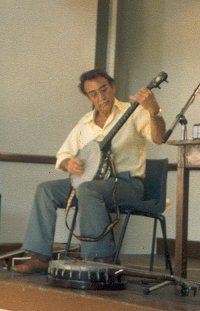

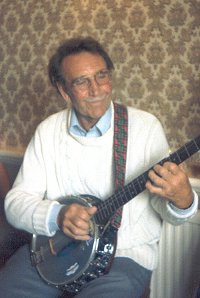

Anyone who heard Bristolian Ray Andrews (1922-1987) playing finger-style classic banjo knew they were in the presence of a special talent. Whatever the occasion, he communicated sheer enjoyment and personal warmth to the listener. Although Ray's first love was the English ' classic' banjo, he was at home in a variety of musical styles in the popular idiom. He could play classical arrangements, pop songs of the day, traditional Irish music, as well as accompanying singers.

He played in theatres in the last days of 'variety', singalongs in pubs, folk clubs, festivals, with the Bristol Banjo, Mandolin and Guitar Orchestra, concert parties, and for dance bands. Ray had a physically demanding working life as a fitter-welder; and often after a full day, starting early in the morning, he would go straight out to play until last orders had been called.

Ray Andrews played for much of his life in working class clubs, pubs, family occasions and community events. His repertoire reflected the context in which he played. For the Swingers dance band and for pub sing songs, he had a long list of familiar material. He accompanied the Swingers on contemporary pop songs and dance music. When he played with Erik Ilott and with the Moran Brothers, he accompanied traditional tunes and songs, and learnt hornpipes and the occasional jig.

He was taught classic banjo style by Harold Sharp, learning tunes from banjo magazines and manuscripts, some dating from the 19th century.One tune, Shaeffer's Jig (a Clifford Essex arrangement) for example, was originally published in Banjo World in 1895. Ray told John Maher in a 1975 interview that he learnt Whistling Rufus from a BMG magazine. As many who knew Ray commented to me, however, he 'could play anything'. And he had a full bag of tricks in banjo technique, especially harmonics.

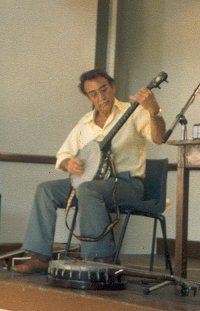

He was a musician for all occasions, and delighted folk club audiences in the 1970s and '80s, very few of whom had ever heard a classic banjo piece before they had heard Ray. The label 'traditional' musician does not fit easily with him, perhaps because he learnt his classic banjo music from notation. He learnt most of his other repertoire by ear,however, especially old music hall and 'community' songs of the early 20th century. Unlike some other classic banjo players, he did not appear to need the notation in performance. Much of his popular repertoire is of the kind often easily dismissed by those of us weaned on 1960s rock and later 'folk revival' music. But it could be argued that Ray's music was more 'connected' to the local community than much of the 'folk revival' or, in its later years, the more formal banjo club movement.

- Part One of this article is an account of Ray's life in Bristol from his birth in 1922 to his early death in 1987. I will also look at the music he played, the musicians he played with, and his repertoire.

- Part Two traces some of the history of classic banjo music in Britain and the Bristol area.

- Part Three looks at some of the historical issues, including the slave origins of the banjo, and the political context of 19th century banjo music.

Thanks are due to all those who have given me information about Ray's life and the classic banjo, especially his family and friends.

I must also give a special mention to the late Andy Rennie of Bristol, who prompted me to start this task. It was Andy who drove Ray, with Jim Small, mouth organ player from Cheddar, to the first Cricklade English Country music weekend, where Ray was recorded with Jim and Bob Cann, by Neil Wayne. One of the recordings from that session appears on the Veteran CD Proper Job, with all three playing Manchester Hornpipe. Several other recordings from the Cricklade Weekend are included on this present CD.

Ray's life

Raymond David Andrews was born on 7th January 1922, an only child of David and Ellen. They lived at number 2 Quakers Friars, in central Bristol, an area which is now known as the location of the City's registry office in the Broadmead shopping centre.

Ray's father David was born in 1889. His father Samuel was from Scotland ; his mother, Annie Fitzgerald, was originally from Fermoy, County Cork Ireland. He spent his early working life as a stoker on steamships until after the First World War. On his return from the Navy, he worked as a boilerman at Manor Park hospital in Fishponds, Bristol.

Ray's father married Ellen Lloyd, known as Nellie. Her father was Josiah Langdon Lloyd, from South Wales. From an early age Ray heard music, since his father played tenor and G banjo, mandolin, concertina, mouth organ, fiddle and phono fiddle. Ray first learned to play the banjo with his father. His mother was not known as a musician, but cousins on his mother's side were singers or musicians. Ray's cousin Gwilym was well known as a choral singer and orchestra leader, and his uncle Harry Lloyd played piano,and encouraged his children to play instruments.

Ray first school was at Castle Green, close to what was the heart of Bristol's shopping area at the time, near Old Market, and across the River Avon from the Bristol (George's) brewery. When he was six years old, the family moved to a cottage in Stapleton village, near the old Wesleyan chapel. His new school was the nearby Church of England school . In 1930, the Andrews family moved to Beechen Drive, to a semi detached house on the new Hillfields estate at Fishponds.

A working life

Ray's school days were completed at Hillfields and Alexandra Park, which he left at the age of 14. He became an apprentice fitter-welder, before signing up with the RAF. In 1941, he helped to install central heating to the Old Council House in Corn Street.

Ray - This was just before I joined up in January 1941 - just in time for the air raids. I worked there with a Bath chap, Jack Humphries. We put in a new boiler and central heating, right up to the Lord Mayor's parlour. The building was full of passageways; some went out towards the river (interview- John Maher- 1975)

During the second World War, Ray saw service in North Africa and Italy. On his return, he spent his working life fitting pipes and welding metal, often installing industrial boilers and commercial heating. He worked for several companies, including Haden Young, Crown House Engineering, and Marriott Jackson and Norris. His work took him to factories and large buildings across the Bristol area. He often had to work away from home, for example at Pontypool during the 1960s.

Brian Whiston of Oldland Common knew Ray in the early 1980s. Ray taught him to play the banjo; and as an engineer, they often discussed their work. Ray told him that he was sometimes known as the ' Big Blow Pipe Man', because he welded half inch mild steel with a large nozzle acetylene torch. He used a 10lb hammer to shift obstinate nuts. His jobs included welding cold roll steel, and erecting gutters to the Concorde hangar at Filton aircraft factory. Ray told Brian that he was once at the top of a ladder, steel welding at Filton, when the acetylene bottle at ground level caught fire.

Bob Riddiford of Alveston, played string bass with Ray in the 1960s. He knew Ray through his work at Filton. He remembers Ray shifting heavy boilers on rollers.

Bob - His hands were always filthy and I wondered how he could play the banjo with fingers like that. His fingers were so big - as if they'd been spread out through years of really hard work. He was a hard working man - not an office worker.

Ray was a skilled worker, and like many, he became a member of a 'poor man's Masons'group. In his case, it was the local Loyal Order of the Moose.

Family

Ray married Elsie Holbrook on June 28th 1947 and in January 1949 daughter Carol (now Eyles) was born, followed by sons David (March 1951) and Michael (December 1954). Ray and Elsie lived first at Beechen Drive, then at Gill Avenue Fishponds, before settling at 101 Vassal Road, Fishponds after1951.

Acrobat

As a young man, Ray had been very fit. According to the late 'Bristol Shantyman' Erik Ilott, Ray performed balancing acts with his father on stage in the 1930s, and was champion boxer at his weight in the RAF in North Africa (letter to Barrie Morgan 1987). According to numerous accounts, Ray would often surprise friends or colleagues by somersaulting or backflipping, sometimes with a banjo in hand. Gary Ward worked with Ray in 1985 for Marriott Jackson and Norris.

Gary - During a lunch break, outside at Frenchay Hospital, we were talking about acrobats. Ray put his sandwich down, took out his false teeth, wrapped them in a handkerchief... and did a back somersault. Then he carried on with his lunch.

In 1985 Ray and Erik Ilott were performing at a Bristol Ship Lovers Society gathering outside the Industrial Museum at Bristol City Docks. A father and son fell into the Docks, and Ray helped pull them clear of the water. According to Brian Whiston, Ray felt he had strained himself rescuing them. Ray later fell ill with cancer, and died on April 2nd 1987. According to Brian, Ray was playing his banjo almost to the very end. He remembers him sitting up in bed, playing the well known banjo tune Whistling Rufus.

Ray's musical youth

In an interview by John Maher with Ray and Erik Ilott in February 1975 (Bristol Folk News Spring 1976: Bristol EFDSS), Ray talked about the music in his family as a boy.  He explained that his father did not play 'classic' finger style banjo.

He explained that his father did not play 'classic' finger style banjo.

Ray - He liked using the fingers but not in the proper orthodox way as we know it now; he had his own style - he was self taught. Then Mum got him (to play) the mandolin, until he was really a very good player - he wouldn't disgrace the Bristol Banjo Club today [Ray here means the Bristol Banjo Mandolin and Guitar Club- the BMG club]. There was music in my mother's family. Her brothers played mandolin and were musically minded. They were in the Joe Jenkins Male Voice Choir - this goes back to 1912. So my mother got her music from her brothers; they played harmonium. They were all put to teachers to play the piano. That harmonium was passed around the family - it had a full set of stops. My youngest aunt had it.

We would play Sunday nights down the Marsh. I joined a local Fishponds concert party. My mother used to sing some old songs - she had a fair voice. The year before last we went to the Golden Lion and she sang a song I hadn't heard before. It was about a church. She did all the verses and didn't forget a line; it was unaccompanied, a really old fashioned piece.

Musical Cousins

Ray's cousins Iris Pearse (born 1920) and Renee Sims (born 1922) of Fishponds were brought up in Barton Hill, where their father Harry Lloyd ran a grocery shop in Corbett Street. They remember Ray and his father when they were young, in Barton Hill.

Renee - He went to the Old Vic theatre in 1937 and won a talent competition, and had to play there every evening for a week. He was always practicing at Beechen Drive. Ray's dad worked at Manor Park on the boilers, shift work. Uncle Dave had to have his sleep, so there were only certain times we could go round to Beechen Drive. If he was on a certain shift that was alright, and then the banjos would come out. It would be Ray and his dad and my dad . My dad was good, he played piano, mouth organ, banjo and mandolin - he would play anything. I had to learn the violin, and Iris played the accordion. Gwilym set the example in our family.

Iris - It was the Salvation Army that started Gwilym off - his family lived in Channons Hill opposite the Salvation Army. We had to learn to play the piano. I could play Lassie from Lancashire.

Renee/Iris - we were the only ones with a car; Ray's parents didn't have one. We went to the pub and Ray would play - we made a small collection. They always wanted Ray to play. My father played piano in the pubs. If Uncle Dave wasn't working, we would go out in the car, 6 of us in it, to places like Frampton Cotterell and Iron Acton. I remember writing a school essay about it. On Sunday night we might go out to Wotton under Edge, to a really old fashioned pub. We'd play songs like Golden Slippers and sing "all those lovely kippers...!"

Renee - I used to dance then; I tap danced in the talent competition and Ray accompanied. Ray won and I didn't. I used to say "How can you judge a banjo player against a dancer?"

In the 1975 interview Ray told John Maher:

There was only one other who went to the Theatre Royal as a kid who was being taught the banjo. That was Ken Scott: he's my age and still on the boards today. He also entered the competition. Don Parish, a xylophone player who had a jazz band was also there, and some singers ...

Renee - Ray and his dad would play at our house in Corbett Street. Only a few had the wireless- we were the musical family. We would be welcome anywhere because dad played the piano. There was a piano at the Lord Nelson. Uncle Dave and Ray would come along - they made a trio - the pub was at the top of Aiken Street where we used to live. Ray's dad used to do a little bit of acting for parties. We would go too, they were a good team, Ray and his dad.

Iris - The banjos would often come out at parties. We would party and sing. They all liked their drink. Ray and his dad played quite 'go-ey tunes'. They'd start off; then they'd get nostalgic and sing the sad old songs. They were welcomed at everybody's houses. I would have been about sixteen when I had the piano accordion. I was always out at weekends. The pub landlords liked us, because if there was music you'd get the people there. We'd do songs, the old songs - all by ear.

Renee - Ray's dad could play the spoons. When we were at their house, out would come the instruments and the flagon of George's homebrew. I joined the ENSA concerts in the War; Ray was there as well. We used to go in a van to Brislington for concert parties in the blackout.

Work, Unemployment, Poverty and Entertainment

East Bristol between the wars

Much of Bristol in the 1920s and 1930s was dominated by industrial life. The City Docks and Avonmouth provided much employment and were an essential feature of city life. The legacy of Bristol's coalfields remained despite several closures either side of the First World War. Speedwell colliery, near Fishponds was one of the last Bristol pits still working. Ray's cousin Renee remembered the area just after the colliery closed in 1936.

Renee - There were fields, orchards and lilyponds . The ground by the old Speeedwell pit was still rough. If we'd been to Aunt Nell's and we missed the last bus, we had to walk home through the fields, past the old mine ; its where the school is now.

When I was 9 or 10, I sometimes had to go to Lysaght's factory in Silverthorne Lane to collect Mr Jossham's wages. He was our neighbour, and his wife asked me to collect the money in case he went straight to the pub after work on the Friday!

Lysaght's main steel and iron factory was at the Netham, by the River Avon, where they made large structures, including bridges. The Silverthorne Lane works made wire netting and galvanised goods like tin baths, buckets and cattle troughs.

Many working class families in East Bristol lived in Victorian terraced houses without baths or inside toilets. They often opened directly onto the pavement. In the Barton Hill area, they had been built for the Great Western Cotton factory workers. Some streets (like Aiken Street) were named after the directors of the company.

In the 1920s the City Corporation had begun to build new estates on the outskirts of the City to replace some of the older houses. The Hillfields estate at Fishponds, where the Andrews family moved, was part of this programme. At the same time, during the 1930s many semi- detached houses for private owners were built. The City expansion and movement out to the suburbs catered for the increased working population. In nearby Kingswood were boot and shoe makers, and at Fishponds, Robinsons printing and packaging works, Pountney's pottery, Parnall's and Charles Newth furniture, Williams fireplaces, and Robinsons wax.

Not everything in the garden was rosy of course, and in Bristol at the height of the depression in 1932, there were 21,245 out of work . In those pre-Welfare State times, many were glad of facilities provided by organisations like the Barton Hill University Settlement, and the Methodist Church at its Central Hall headquarters. At various times, the Bristol BMG club met at both the Barton Hill Settlement and the Central Hall.

The Barton Hill University Settlement had opened as an education centre in 1911; an idea of the staff and students at the University of Bristol. The centre ran children's clubs, a play group, a pre-natal clinic, a mother's school, and an open air school for 'delicate' children. (see Barton Hill, published by Barton Hill History Group; Bristol 1997)

Although the Lloyd sisters were not from the poorest family in the area, they were able to use many of the Settlement's facilities:

Renee - You paid tuppence and they put on a play or a pantomime; we had to sweep up afterwards. We used to go swimming at boarding schools like Red Maids, when they were on holiday in the summer. There was a church in Cobden Street where we had our school dinners; if you were really poor, you would get free boots. Hardly anyone paid cash in the shop - it was always 'in the book', and they'd come over on Friday and pay for it. Our clothes were always being passed on. There were big queues at jumble sales; and a rag and bone man came around.

In 1922 the Bristol Methodist Church appointed the Rev John Broadbelt as new Minister at the Central Hall, Old Market. Under his leadership, the church's 700 members undertook much fundraising and organised children's breakfasts, a soup run, and a boot repair service. The Hall also put on 6d concerts (Bristol Between the Wars ed D Harrison ; Bristol 1984) .

The Central Hall, according to John Hopes of Siston, had been organising entertainment since the late Victorian years. Their shows were in the 'light classical' vein, and included singers, pianists and banjo and mandolin players. The 'classic' banjo music repertoire fitted easily into such concerts. In the autumn of 1934, the Central Hall 'Bristol Popular Concert' series was under the Rev Stanley Southall, with musical director Arthur J Baker. The national director of such concerts was Wilfred Stephenson from Sheffield. The series included recitals by a violin and piano duo from Serbia, opera principals from Covent Garden, and The Roosters Concert Party. The Central Hall concert programme continued after the Second World War. Other church based concert programmes also a featured similar entertainment.

In the more commercial music world, Bristol had several thriving music hall theatres, some of which had also been used as cinemas almost as soon as they opened. Many well known early twentieth century music hall and variety performers played in Bristol at one or other of these venues. Familiar popular songs no doubt filtered in to family music repertoires in this period from the halls, the radio and 78 rpm records.

Ray and the Classic banjo 1928-1939

During the 1920s, dozens of banjo, guitar and mandolin clubs existed across England, including Manchester, London, Leeds and the West Country. The Bristol BMG club was formed in early 1928, and one of its first members was Harold Sharp, who was Ray's first 'proper' banjo teacher. According to John Hopes, who knew Ray as a member of the Bristol club from the 1960s, Ray played with his father at a BMG meeting in the autumn of 1928. If this is true, he would have been barely six years old! Having learnt by ear from his father, Ray told John Maher that he 'had to start all over again' with Harold Sharp. This was Ray's introduction to the world of the classic finger style banjo, learning from standard musical notation. Harold Sharp had played banjo since the early 1900s. From 1928 he played with Lionel Saunders (who was the first president of Bristol BMG) and Alf North (the founder of Bristol BMG and its first secretary) as 'The Bristol Banjo Trio'.

Another young player at the same time was William Ball, who had performed with his father at the first meeting of the club in 1928. Bill Ball went on to become the most acclaimed classic style player in Bristol until his death in 2000. In a letter to Norman Sharp (Harold's grandson) in 1997, he remembered Harold Sharp as a banjo maker and player.

Ball - My father had an open back banjo and its neck was faulty. Harold made a new one and fitted it to the hoop' Bill Ball,who was often keen to express an opinion in correspondence, commented "(the neck) was not slender enough compared to a new banjo. The tone was poor ... and I rejected it and kept my Clifford Essex one."

Harold Sharp made a zither banjo for Ray, which he kept until he died. Ray rarely played it in public, as he preferred the louder standard G, 5-string variety.

Sharp (1881-1964) was born in Wickwar, Gloucestershire. His father was an engineer at Wickwar brewery, from a family of millwrights. The family moved to Redcliffe, Bristol in 1891, where his father worked as a marine engineer at Charles Hill's shipyard in the City Docks. Harold became an engineer's pattern maker, working for several different local firms. As a craftsman in wood, he was making banjos by the early 1900s. He spent much of his adult life at Ridgway Road Fishponds; his last job was as a shop fitter with Parnall's factory.

Norman Sharp has one of his grandfather's zither banjos, made in 1905. He had a few lessons from Ray in the early 1980s, so completing the circle! Ray did not charge for the lessons; this was not unusual, according to many of his pupils.

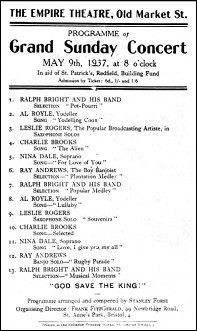

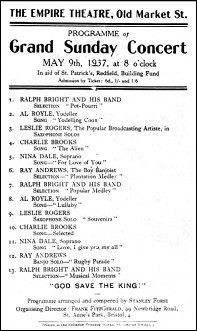

Following his success at the Theatre Royal talent contest at the age of 15, Ray became known as 'Bristol's Boy Banjoist' (a title also given to Bill Ball). He was booked to appear at several Sunday night variety concerts. They were often organised to raise money for various causes, like church building funds, and the British Legion. Many were compered by Stanley Forse, who booked the performers. In May 9th 1937 Ray appeared at the Empire Theatre, Old Market Bristol, a well known music hall venue. According to the programme, he played Plantation Medley and Rugby Parade (by Olly Oakley); he later appeared at the Stoll Picture House Bedminster and at the Kings Cinema Old Market (on May 14th 1939). He also played at the Ambassador Cinema in Kingswood with the Bristol Banjo Club.

During the 1930s, Ray's father bought an Edison Bell phongraph:

Ray - my Dad bought it for half a crown. It had a recording unit to fit onto to phonograph. We used to make our own records... (we would) rub them down and recut them. We used to make a sketch... for example, going to a Rovers football match.We'd make the noise of a rattle, and the shouts of the man selling programmes. This was like early wax cylinder recording. It was our fun. The cylinder was packed in a box with compressed cotton wool; it was well looked after ...(J Maher 1975 interview)

Ray did not make any 78 rpm records, but later made one cassette in the 1970s, recorded by Erik Ilott (see Appendix)

Wartime

Ray signed up for the RAF in 1941.

Ray - I took the banjo with me to North Africa and Italy - I played at church services, under canvas, in Italian POW camps. When I first joined the services, with Ted Kirtley [another banjo player] I had to go to Weston for the square bashing... the flight sergeant Sanderson said "Any musicians?" I put my hand up. He said "I'm forming a little concert party to do all the batteries in the area." There would be 3 or 4 a week at an ack ack battery; one was at Brent Knoll. We'd get back about midnight. We were billetted in hotels on the front at Weston, towards the pier overlooking Knightstone marina. We were often the worse for drink. The flight sergeant was a ventriloquist. I joined the station dance band. When we went to Pembrokeshire, I played for off-duty dances. Do you know - I must have travelled thousands of miles in the War, and never met another banjo player - (J Maher interview)

The 1950s and 1960s

The Bristol BMG club was reformed after the War, and Ray joined in 1950. He took part in Banjo Federation national competitions, winning second and third prizes in different years.

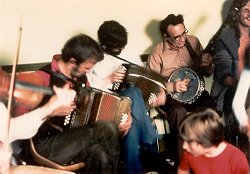

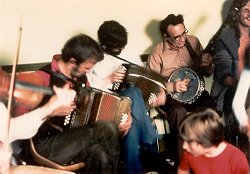

John Hopes, a mandolin specialist, remembers Ray playing a duet with an accordian player at the Congregational Church Hall Stapleton Road Bristol in 1960. John later joined the BMG club when Ray was an active member.

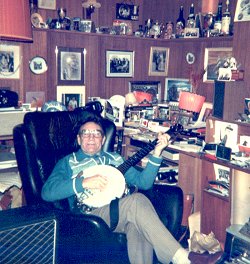

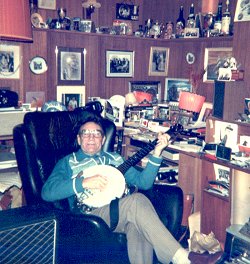

John - Ray was a warm and accommodating personality; welcoming and encouraging newcomers to the fretted instrument world. The door of his home was always open to the enthusiast and was an 'Aladdin's cave' of banjo interest.

Alan Quirk of Pill played bass, banjo and piano with the BMG in the 1960s. He remembers practicing at a church hall in Days Road, St Philips. Ray would arrive on a solo motorcycle with his banjo strapped to his back. He says Ray always played with his foot stamping the floor.

Alan's father in law, Stanley Hill, played plectrum banjo with the BMG club for many years.  A 1954 photograph of the club shows Ray second from the right in the back row, with Stanley Hill to his right. Stanley Hill had a band in the 1940s with Cyril Harper and Eddie Howell known as 'The 3 Hs'. The photograph was included in a programme for a concert at the Odeon Theatre Kingswood on 27th March 1955 in aid of Hanham old age pensioners 'Memory Hall' building fund. We have just heard that Stanley Hill died in February, 2001, aged 102.

A 1954 photograph of the club shows Ray second from the right in the back row, with Stanley Hill to his right. Stanley Hill had a band in the 1940s with Cyril Harper and Eddie Howell known as 'The 3 Hs'. The photograph was included in a programme for a concert at the Odeon Theatre Kingswood on 27th March 1955 in aid of Hanham old age pensioners 'Memory Hall' building fund. We have just heard that Stanley Hill died in February, 2001, aged 102.

In the 1975 John Maher interview, Ray referred to some of the musicians in the 1954 photograph.

Ray - There is Bill Jenkins; he was taught by Tarrant Bailey [a well known banjo player from Bath], Sally, Stan Hill; he was taught by Harold Sharp, my teacher ; there's Dick Elbourne - he had a Cammeyer Vibrante, and was a good player from Yeovil. The man who took the photo was Archie Frape, a tenor banjo player ; he had an Essex concert grand ...

From the 1950s, Ray often played with the late Bill Stone, another BMG member, as a duet. Bill was a plectrum style tenor banjo player, who had been taught before the second World War by Horace Craddy. The Craddy family were well known in Bristol banjo circles, going back to the 1890s.

Ray and Bill duetted at charity functions, concerts, old peoples clubs. A 1985, family video shows them playing at a concert given by the Bristol Central Male Voice Choir.

In the 1950s, Bill, his brother Ken and an unrelated Stone (Brian) formed a skiffle group. Their father was Moss Stone; not surprisingly, they called themselves The Rolling Stones. On the demise of the skiffle boom, they broadened their repertoire to include country and western . In 1965, there was a legal battle with the other 'Stones' which resulted in them being unable to continue with their name. A publicity leaflet for the Bristol Stones band at the time said 'Bill Stone plays a very fine banjo and can perform equally well Liszt's Liebestraum or Bye Bye Blues. Bill is a devotee of the great Eddie Peabody' [an American plectrum style player]

In the 1950s, Bill, his brother Ken and an unrelated Stone (Brian) formed a skiffle group. Their father was Moss Stone; not surprisingly, they called themselves The Rolling Stones. On the demise of the skiffle boom, they broadened their repertoire to include country and western . In 1965, there was a legal battle with the other 'Stones' which resulted in them being unable to continue with their name. A publicity leaflet for the Bristol Stones band at the time said 'Bill Stone plays a very fine banjo and can perform equally well Liszt's Liebestraum or Bye Bye Blues. Bill is a devotee of the great Eddie Peabody' [an American plectrum style player]

Ken and Bill Stone also played gigs with Stanley Hill, and a finger style banjo player, Charlie ' Smokey' Lewis. He, like Ken, was a gas fitter. Ken doubled on piano for these pub music sessions; their repertoire was singalong and popular music of the day. Ken is also a fan of the ukelele; he has 'George Formby' model bought in 1932. (interview Ken Stone, 2000)

Bob Cooper from Hanham, is a mandolin player and was a BMG member in the 1960s. He often drove Ray to performances after Ray had lost his driving licence. He says that at one Federation competition, the adjudicators had to find a small fault otherwise the Bristol BMG orchestra would have won every cup and trophy.

Ray played in many different contexts, including informal pub sessions. Bob Riddeford, bass player, played with Ray for two years in the 1960s:

Bob - Ray was working at Patchway at the time, which is how I met him. We played 'out of the blue' at the Rainbow Club at Stoke Gifford.We also played at a pub in Olveston. Sometimes we had a piano player, Bill Rees, with us . The Rainbow was at that time out in the country; it was run by a man called Shergold. We played all sorts of music; marches like the Golden Eagle, singalong tunes like Cockles and Mussels, and brass band tunes. I knew all these tunes because I'd played for the troops. We played every week at the Rainbow. Ray must have been out playing a lot. He sounded like a band when he played marches. He also played finger style on quieter, 'country' tunes; he played leads,chords and runs. Ray would go on all night. We stopped playing together when I joined the Severn Jazzmen. Ray wasn't interested in playing jazz.

1970-1987

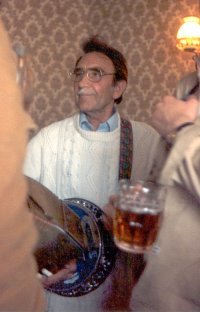

During the last twenty years of his life, Ray became well known throughout the Bristol area because of his various musical interests. He played in many informal sessions, especially at the Golden Lion in Fishponds Road. He took his banjo to join in with the pub pianist for sing song and music sessions.

The Bristol BMG club began to decline in numbers in the 1960s. Some members wished to extend the repertoire beyond the 'old fashioned' pieces dating back to the nineteenth century; they wanted to play more up to date popular material. The club finally folded in the early 1970s. Its eventual successor was the Fingers and Frets Club which still meets today. Ray was often present at their gatherings. About the same time that the BMG club finished, Ray was invited to join the Swingers, a band which played a variety of music in working men's and Irish clubs. Through the Swingers, Ray met and played with Irish traditional fiddlers, Jim and Gerry Moran.

During this period Ray continued to take pupils; the teaching sessions were often very informal. Ray also joined the Volunteers Concert Party. But Ray was probably best known at this time as a performing partner and accompanist to Erik Ilott, the Bristol Shantyman. Through Erik, Ray became a member of and regular performer at the Folk Tradition club, which met originally at the Old Duke, and then at the Nova Scotia in Bristol.

The BMG and the Fingers and Frets club

John Hopes has been the main force behind the Fingers and Frets club since its formation. He knew Ray well from 1960 when the BMG club had as many as 50 playing members of banjo and mandolin. He says that Ray was upset when the Banjo club folded. John said that Ray sought other places to play and musicians to play with.  This led him to joining the Swingers and working with Erik Ilott. Nevertheless Ray was always a welcome guest at Fingers and Frets events for banjo mandolin and guitar players, being given solo spots at their concerts. He played at the Longwell Green, Bristol Fingers and Frets convention in 1978.

This led him to joining the Swingers and working with Erik Ilott. Nevertheless Ray was always a welcome guest at Fingers and Frets events for banjo mandolin and guitar players, being given solo spots at their concerts. He played at the Longwell Green, Bristol Fingers and Frets convention in 1978.

Ray and Erik Ilott

Ray's friendship and musical partnership with Erik Ilott intensified in the 1970s . Erik had known Ray for many years. In a letter written from Auckland, New Zealand after Ray's death, Erik said:

Erik - My first memory of Ray is as a little boy. Ray was dressed in shorts with an Eton collar, looking tiny and diminutive with a banjo seemingly bigger than himself, playing in Bristol Music Halls where he was known as 'Bristol's Boy Banjoist', and acknowledged as a boy genius on the banjo.

In the 1975 John Maher interview, Erik tells how he first met Ray -

Erik - Some years ago I met a chap called Ron George who said that England's best banjo player is a chap called Ray Andrews and he lives in Fishponds. He was always on about this 'Ray Andrews' and I got fed up and decided to try to find him. I got on me bicycle one day and I toured round knocking on doors, asking if anyone knew ... (him) I found three banjo players, they were not very good... eventually I knocked on your door, Ray, and he had me in here, and I said to myself 'this is your man'.

The first time I played my bones in public for years was down at the [Folk Tradition] club at the Old Duke [Bristol]. I didn't know anyone was interested. It was only Stan Hugill who got me down.

Ray commented in the interview that if it wasn't for Erik, he would only be playing at home or with the Banjo Club - but this might be an overstatement, given Ray's knowledge and experience of various aspects of live music on Bristol.

Ray and Erik performed together at folk clubs, festivals, at the Bristol Ship Lovers Society, and on local radio. Erik's free style of singing never fazed Ray, who was able to keep up with the often irregular rhythm. Erik in turn accompaned Ray's classic tunes on bones.

Ray and Erik performed together at folk clubs, festivals, at the Bristol Ship Lovers Society, and on local radio. Erik's free style of singing never fazed Ray, who was able to keep up with the often irregular rhythm. Erik in turn accompaned Ray's classic tunes on bones.

In 1974 they played at a competition at a Llangollen Festival. According to Bob Cooper, they competed in a class for 'Britain', and came second to Portugal. Ray often recorded events he was playing at or listening to, and he recorded an informal session at Llangollen. On the cassette Ray and Erik can be heard swapping songs and tunes in between the pints. Erik starts off with a couple of George Formby ukelele songs, then Ray follows with I'll See You in my Dreams, a Gilbert and Sullivan medley, and the Harry Lime theme.

In the late 1970s, Erik recorded Ray for a cassette, Banjo Maestro, issued on the Foc'sle label. The cassette has 13 tracks of classic banjo tunes and arrangements by Emile Grimshaw, Joe Morley, Olly Oakley and others. Two of the tracks, Minuet in G, and Annie Laurie are described as 'arr. Andrews'. The minuet, according to Ray in the 1975 interview, was arranged by Bernard Sheaff from a Beethoven original.

According to the late Tony Whitfield, a close friend of Ray's for many years, the original recording was at Vassall Road, onto 3 reels. Erik later edited it onto one cassette at his house at Kingsdown, but the tape quality was not the best available! At the session at Vassall Road, the first take on one track was accompanied by a loud thumping, which turned out to be Ray's right foot. Erik then put a cushion under the foot, only for Ray to carry on tapping with his left foot!

The Folk Tradition Club

'Alongside Bristol Quay'

'Alongside Bristol Quay'

In the early 1980s, John Shaw of the Folk Tradition club produced a compilation of traditional and other songs, dance tunes and stories from the Bristol area as Alongside Bristol Quay. One of Ray's hornpipe sets was included in the collection as Ray Andrews' Hornpipe. Ray called most of his hornpipes The Bristol Hornpipe, but this one was a mixture of the Greencastle Hornpipe and the Liverpool Hornpipe. Barrie Morgan, who played banjo at this time, and knew Ray well, says he learned hornpipes from Erik Ilott. He may also have learned other tunes from EFDSS publications. Alongside Bristol Quay formed the basis for a number of live shows in which Ray and Erik took part,as well as a BBC Radio Bristol performance

The Swingers Band

The Swingers were a dance band who were down to their last two members at the same time, in the 1970s, that the Bristol BMG club was in decline. One of them, Bill Gould, knew the BMG and it was his suggestion to seek a banjo player from their ranks. The organiser/leader of the Swingers was Harry (aka Henry) Edwards. John Hopes suggested Ray Andrews as a possible addition to the band. His joining apparently coincided with the final meeting of the Bristol BMG club. He stayed with them until the band finished in 1986.

The Swingers were a typical working men's club dance and singalong band. Their line-up varied over the years but included Paul Nolan (drums), Dave Pearce (electric bass guitar) and sometimes an accordion player. They played at venues like the Holy Cross Social Club, the Temple Meads Railwaymen's club, the Linden Hotel Kingswood, St Bonaventure's club, and the Liberal Club at Clevedon. The Bristol area still has several such clubs . Many of them attracted the label 'Irish club', but were not exclusively Irish. The Swingers often played each Friday and Saturday night at a club; and for about two years, Sunday lunchtime at the Holy Cross club, in Southville, next door to the local Catholic church. The Swingers were usually paid a small fee, and were Musicians Union members.

Their repertoire included old time ballroom dances, country and pop songs; older 'music hall' songs, and easy listening, modern popular songs. A typical set might include the Gay Gordons, an Irish / Scots tune medley, songs like Spanish Eyes, and waltzes.

The Moran Brothers

It was through clubs like the Holy Cross that Ray met traditional Irish fiddlers, Jim and Gerry Moran.

Gerry - Ray started to come when we used to play. My brother used to pick him up . We all played together, mostly jigs and reels, hornpipes, and some slow airs. Ray joined in with us; he'd do a spot on his own as well. He'd sometimes play melody with us. He didn't know the names of the tunes, but then neither did we know the names of many of them, either! Ray used to play Carolan's Concerto. At the Holy Cross session, we'd get singers, accordian players, fiddlers... it ended when the vicar moved away.

We learnt our music back home in County Leitrim. I came to Bristol about 40 years ago, after a short time in London. My brother stayed in London longer than me. We were in the Connaught Ceilidh Band. We played Swindon, Bath. Lots of places.We had Tommy Ford, accordian, Brendan Devitt drums. We knew people like Bobby Casey. We had 100s of tunes. We played Sligo style; a bit faster than say Kerry style. Jim lived near the Arsenal ground, and he knew all the people at the Favourite in Islington

Mike Hughes of Bristol knew Gerry and Jim Moran in the 1970s, and remembers a gig at the Buckinghamshire Police ball, when he played fiddle with Ray and Erik Ilott . He says the Moran Brothers were once coal miners in Co Leitrim .

The Volunteers

The Volunteers were a group of performers who made up a concert party . They gave shows at homes for the elderly, hospitals, village and church halls. They had a variety of talents. The musicians at various times included Ray, with other banjo players like Bill Stone, Bill Gould, Tony Counter, pianists Fred Darlington and Pat York, singers like Ann Honey, and Tony Zefara (keyboard and clarinet). The organiser and MC for a time was Bill Everall. Later Tony Whitfield was also MC ; he played washboard and bones and read his own poems. The group sometimes had a conjuror, or a violinist, and 'light classical' pianists or singers.

Ray recorded a Volunteers concert at Little Stoke in April 1980. Tony Whitfield was the MC. The band played old songs and tunes like an Al Jolson medley, and there were parlour songs like Just a Song at Twilight. Ray's solo spot included Shaeffers Jig, Rugby Parade and The Kilties (by Emile Grimshaw). The band ended the event with Grandfathers Clock and the waltz song Maggie.

Ray's Front Room: Sessions, recordings and pupils

The front room at 101 Vassal Road Fishponds was Ray's music room ; a shrine to the banjo. Musicians gathered here to practice; to learn from Ray, or generally gossip and socialise. Elsie was usually on hand to provide refreshments to go with the beer. Ray recorded many sessions and his own playing here. His cassette collection ran into hundreds, mostly copied from other sources or live sessions. He also recorded music from the radio. Sometimes the tape was left running so that conversation continued after the music. Only one box of tapes remain, which include music by the Swingers,  a concert by the Volunteers,

a concert by the Volunteers,  and music from the 1984 Reading banjo festival. On one cassette Ray recorded himself playing Shaeffer's Jig (sound clip, right), Darktown Dandies (sound clip, left), a hornpipe set, Blackthorn Stick, Kaffir Walkround and Cammeyer's Humouresque. The cassette gives a flavour of Ray's live playing, despite its lo-fi quality!

and music from the 1984 Reading banjo festival. On one cassette Ray recorded himself playing Shaeffer's Jig (sound clip, right), Darktown Dandies (sound clip, left), a hornpipe set, Blackthorn Stick, Kaffir Walkround and Cammeyer's Humouresque. The cassette gives a flavour of Ray's live playing, despite its lo-fi quality!

Ray as teacher

Ray taught many pupils from the 1960s to the 1980s. John Hopes says that one was 'Peter the Painter' who had originally played the banjo as a professional soldier at a hill station in India. Bob Stuart of Horfield, Bristol played zither banjo with the BMG club in the early 1970s and had tuition with Ray. He remembers Ray playing a Clifford Essex Clipper banjo, and says Ray often wore down the frets. He tried to repair them, and when this was unsuccessful, he would play fretless . He would eventually buy a new banjo. Bob remembers other players at the time including Don Shaddock (plectrum banjo), Harold Marsh, and Ernie Elliott (banjolele).

Ray taught many pupils from the 1960s to the 1980s. John Hopes says that one was 'Peter the Painter' who had originally played the banjo as a professional soldier at a hill station in India. Bob Stuart of Horfield, Bristol played zither banjo with the BMG club in the early 1970s and had tuition with Ray. He remembers Ray playing a Clifford Essex Clipper banjo, and says Ray often wore down the frets. He tried to repair them, and when this was unsuccessful, he would play fretless . He would eventually buy a new banjo. Bob remembers other players at the time including Don Shaddock (plectrum banjo), Harold Marsh, and Ernie Elliott (banjolele).

Norman Sharp was taught to play The Kilties from chord positions in the early 1980s. Another of Ray's pupils was Phil Davidson, a well known bluegrass player and banjo maker from Bristol.

Brian Whiston was also taught to play from a chord tablature method, which he says Ray may have adapted himself from a guitar manual. He gave the different chord positions different names. He would then write out a tune like Grandfather's Clock completely in chord positions. When Brian became reacquainted with banjo standard Whistling Rufus, he remembered that he had played it with the British Railways Accordion and Harmonica Band as a teenager in 1953 in Peterborough. As a 15 year old Brian had played ukelele banjo.

Tony Whitfield said that Ray learnt a new tune in meticulous fashion from notation, phrase by phrase. When he was satisfied he would move on to the next phrase, until the end. When he played in public, he would then play from memory.

Bob Cooper says Ray often taught small groups together, and that he did not teach from notation. From music given to Brian Whiston, it seems that this was not always the case. Ray wrote out exercises for his pupils. Whether they came from printed banjo manuals is not clear, however, but he would have expected his pupils to pick up at least a rudimentary knowledge of musical notation. An example is a 'Study in triplets of chords' for Where Have all the Flowers Gone, a series of arpeggiated triads mainly in G and C, which may have come from a Pete Seeger's manual. He also wrote out a sheet of 'thumb and finger' exercises, as well as a tune The Mountain.

Ray's Repertoire

As we have seen, Ray's musical life included working with others as an accompanist, with the Swingers and with Erik Ilott. When he played solo, led in duets or in small ensembles, his repertoire could be divided into three kinds:

- a) mainly pre-World War Two popular and music hall songs.

- b) classic banjo compositions or arrangements.

- c) Irish traditional or traditional-based tunes.

In his banjo case, Ray left several tune lists. The lists contained 42 popular or music hall songs and 8 Al Jolson songs. There were about 80 classic banjo compositions or arrangements, and 3/4 Irish tunes or sets. He played other material which was not on any of the lists, but the list of 'classic' tunes is probably very close to his complete repertoire of this type. For those who heard him play at the Nova Scotia club, it is fair to say that Ray probably had about a dozen classic tunes that he played more frequently, for example White Coons, Whistling Rufus and Shaeffers Jig. Other, more difficult, tunes may not have been played very often as his technique may have declined compared to twenty-thirty years earlier. There are 20 different composers, including Ray himself as arranger. 13 of the tunes do not have identified composers. The classic banjo composers who appear most often on the list are Joe Morley and Emile Grimshaw. The complete list of tunes can be found in the Appendix.

The English Classic Banjo Tradition - its origins and development

English 'classic' banjo music could be described as an amalgam of different styles. It includes, for example, Victorian 'parlour' music, military marches, dances like the polka and schottische, and music influenced by the nineteenth century burnt cork minstrel shows. Later, the cakewalk and ragtime crazes influenced the music in the last few years of the 19th century. By then, music specifically written for the banjo had been published and recorded in a variety of arrangements, often with piano accompaniment. The same music was sometimes also arranged for mandolin, guitar and other instruments.

The 'refined' European banjo music of the time is far removed from the other major influence - slave plantation music from the United States and the West Indies. Songs, dances and banjo and fiddle music of African American slaves were used by the early black faced minstrels. The banjo became very popular from early minstrel shows of the 1830s and 1840s. At the start, the interest of Royalty and other wealthy patrons was a factor in the banjo and minstrel shows becoming fashionable, and this continued later in the 19th century. At the same time,the growth of the entertainment and music 'industries' played a large part in popularising the instrument. The great interest in the banjo in Britain was mirrored in a similar development of 'classic' banjo in North America. Banjo music in America and Britain to some extent developed together, since sheet music was often published in both countries at the same time. In Bristol, as in many other places, interest grew in the new banjo repertoire. Teachers used the new published manuals to further this interest.

The banjo in Britain

I have not researched primary sources to establish whether any banjo-like instrument was played in Britain before the 19th century. However, contemporary writing in the 18th century indicates that the banjo was being associated with West Indian and African-American slaves. Charles Dibdin, the London actor, singer and playwright, had written an opera The Padlock for the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1768 with a comic character, a black servant Mungo. In 1790 he wrote a song for a show The Wags - or the Camp of Pleasure, with the lines 'One negro with his banja; me my jenny come ... as troo a sweet a stranger, me my banja strum' (Dan Emmett and the Rise of early Negro Minstrelsy, Hans Nathan, USA, 1977, and Yesterdays: Popular Song in America, C Hamm, London, 1983). Dibdin himself toured widely, including to Bristol, where he may have performed at the annual St James's Fair (Bristol at Play, Kathleen Barker, Bristol, 1976).

Early minstrels

The campaign against the slave trade in the late 18th century until its abolition saw a number of art songs and broadsides about slavery. But alongside the growth of radical ideas and activities inspired by the French Revolution was found something less enlightened. In the theatre, African-Americans were a subject for caricature and imitation. Negro slave servants, to be found in many aristocratic households, were portayed as figures of fun. Charles Dibdin was possibly the first of many early negro imitators. Their acts later developed into burnt cork black-faced minstrels in the 19th century. Nathan [op cit] comments about Dibdin's act 'all this appealed to the men with the powdered wig and literary education' unlike in America, where the same type of performance 'appealed to the rough and common man'. The English comedian Charles Matthews presented a runaway slave called Agamemnon in a recitation in 1822 in Philadelphia (Nathan chapter 3). Nathan and other writers suggest that in the early 19th century, North American and English popular music and entertainment often ran in parallel.

Early American white minstrels included the banjo in the shows. Two of the earliest were Thomas Dartmouth Rice and Joel Sweeney. Rice toured English theatres in 1836 with great success. He became known for two distinctive stereotypical characters with associated songs. The first Jim Crow, was a rough plantation character; the other the 'dandy' Zip Coon, whose tune was later to become well known as Turkey in the Straw (Nathan ch 4). Nathan shows that many of the tunes used by the early minstrels were related to English and Irish dance tunes. One example, Sich a Gittin Upstairs is said to be similar to the Morris tune Getting Up Stairs, and Zip Coon to Miss Mcleod's Reel.

Joel Sweeney and one of his pupils William Whitlock (later with Dan Emmett's Virginia Minstrels) learnt the banjo from plantation slaves. Sweeney added the short string associated with the 5 string banjo. He performed before Queen Victoria, who was said to have presented him with a belt containing gold coins (Conway p107). In 1843 Emmett toured Britain with the Virginia Minstrels . The following year, a set of his tunes was published in London by d'Almaine of 20 Soho Square (Nathan ch 10).

From the 1830s, minstrel shows were a major part of commercial theatrical and popular entertainment in both America and Britain. The typical line up of a minstrel band was fiddle, banjo, bones and tambourine.Some later bands also included concertina or accordion. Minstrels performed at music hall saloons and as street musicians. In the mid to late 19th century,such bands were common in London. According to The Buskers (D Cohen and B Greenwood; David and Charles 1981) 'the streets were full... of such groups as... the Ethiopian Serenaders, The Ohio Serenaders... sometimes known on the street as the Somerstown Mob... or the Whitchapel Mob'.

Minstrel music became part of popular culture very quickly. In Bristol in 1843, a broadside written by Thomas Cook was printed by W Taylor of 39 Temple Street to celebrate the launch of Brunel's SS Great Britain . The second verse contains the lines ' ...and Peg Leg Poll from Lewin's Mead will dance with Jim Along Josey' (Alongside Bristol Quay, Shaw, Bristol 1984) . Jim Along Josey was a character and song in an American musical drama The Free Nigger of New York. The song was published in 1840 and was said to have been performed by John Diamond, a black faced minstrel.

Stan Hugill's Shanties from the Seven Seas gives several examples of shanties and sea songs with minstrel roots. Some of these songs or versions of them may have been current on ships sailing from British ports like Bristol and Liverpool. Hugill collected many shanties from 'Harding the Barbarian', a black Barbadian seaman who sailed on Yankee, British and Bluenose sailing ships. Two of his shanties, almost certainly of minstrel or plantation origin, are Gimme de Banjo, which refers to a 7-string banjo, and The Old Moke Pickin on the Banjo. Such songs suggest that seamen might have brought banjos with them during the 19th century. Hugill's references show that minstrel songs and the banjo had become part of the maritime oral tradition.

At a circus in North Street Bristol on April 23rd 1852, the entertainment included a... Singing Dog and a Nigger Clown Jonathan Harlow, who will introduce never to be forgotten Nigger Melodies and Virginia dances (Wall Poster ; Bristol Record Office). The wall poster has a drawing of a white fiddler accompanied by a small dog. The circus was sponsored by the local Licensed Victuallers Association, one of whose prominent members was the owner of Doughty's Cider House in Broad Street Bristol. Doughty's Tavern was well known for its concert hall - an early music hall. In 1845, one of the performers at the hall was a young E W Mackney, who later became a well known black faced entertainer, playing banjo and fiddle (Early Music Hall in Bristol, Kathleen Barker, Bristol Historical Association, 1979). Mackney later appeared in many concert rooms in London and at Sadlers Wells (G Keeler BMG magazine 1929).

The minstrel show and the banjo

Early banjos had been made with a gourd resonator, then with wooden hoops. According to G A Keeler (BMG Oct 1929) the first brass shelled banjo was made in 1838 by Dobson in four different sizes. As the instrument developed, metal hoops gradually replaced wood rims, and wire strings began to be used instead of gut ones. Most banjos at this time were smooth necked,unfretted.

Before the 1860s many banjo tutors had been published in America, for example by Thomas Briggs and Frank Converse. In 1863 in England, E W Mackney published a banjo tutor, in 'American' notation. In America the instrument was treated as a transposing instrument, but later English banjo music was written in standard notation, to sound as written. It was not until 1909 that American banjo music was generally written in standard notation.

The minstrel shows began to grow from their small scale beginnings. Probably the most important English company was that run by Moore and Burgess, started in 1859 by George Washington 'Pony' Moore. The Moore and Burgess Minstrels were based at the St James's Hall, Piccadilly from 1871 to 1904. Many banjo players performed with the show, as well as black faced singers like Eugene Stratton. The show had a large orchestra, and as it progressed it probably began to resemble a more modern variety show, with the banjo less important (Minstrel Memories: The Story of Burnt Cork Minstrelsy in Great Britain 1836-1927, Harry Reynolds, London, 1928).

In Bristol, minstrel shows were staged at the Theatre Royal in King Street. In March 1869, there was a show by 26 performers, 'including 16 real negros from the plantations of America'. It was billed as 'The Great American Slave Troupe and Japanese Tommy' [!] (Bristol Times and Mirror, 15th March, 1869, K Barker's archive at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection). This show reflected the increasing number of African-American performers visiting Britain in minstrel shows.

From about the 1870s, many theatres began to put on Harriet Becher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. One national show in 1878 featured the American banjo player Horace Weston. Uncle Tom's Cabin was regularly performed at the Theatre Royal Bristol, for example in 1887, 1895 and 1897 (K Barker Theatre Royal archive). One of these shows included banjo players.

Minstrel Shows 1870-1900 : Banjo Compositions ; the origins of 'classic banjo'

G Keeler's article in BMG (October 1929) suggests how banjo music, developed a distinctive European or English flavour. The early music hall and circus minstrel acts included banjo players, combining clowning and singing. One group, Pell's Ethiopian Serenaders, played at the St James Hall, Piccadilly. Their line up was Pell (bones), Harrington (concertina), White (violin), Stanwood (banjo), and German (tambourine). They performed 'humorous and sentimental ballads like Lucy Neal and Mary Blaine'. Their act finished with a banjo piece The Railway Overture which Keeler says was 'the Highland Fling or Scotch Fling'. The piece was apparently published in 1877 in Metzer's Banjo Tutor.

By the 1860s, many of the smaller London music halls were being replaced by more 'respectable' theatres like the Alhambra and the Tivoli. Keeler comments:

This was the period of the Victorian polka, the galop, the deux temps (a very quick two step). Hence the large number of polkas, polka-marches, etc... written for the banjo.

The English banjo 'tradition' therefore essentially grew out of the minstrel shows . The popularity of the instrument amongst the middle class and aristocracy resulted in composers and arrangers using European style dance tunes, marches, and more 'genteel' melodies. An example, in Cameron's Banjo Tutor in 1883, was an arrangement of Adieu to the Forest by Mendelssohn. The tutor was produced by W E Ballantine, who wrote a second manual in 1898. His clients included the Marchioness of Ripon, the Lady Rivers, and the Rt Hon Earl of Dunraven. (Keeler BMG Oct 1929).

Another new composer was Arthur Tilley, who according to Keeler, ' by the early eighties had composed several tuneful numbers...' including The Premier Banjo March, The Demon Jig and the Coquette Valse. Tilley made banjos; his prize winning products were exhibited at many trade fairs. He was another banjoist who performed before the aristocracy; in his case the Prince and Princess of Wales and the King of Greece.

The Bohee Brothers

The new banjo repertoire was not completely removed from American minstrel or music hall influence. In 1881 a large troupe from America, Haverley's Coloured Minstrels, toured England. The Haverley's included banjo players James and George Bohee, who were American /Canadian born of mixed African-American origin. They established a reputation for their virtuoso playing. When the Haverley's returned to the USA, they stayed in Britain and set up their own minstrel company (H Reynolds op cit).

According to Keeler, a further company, known as Haverley's Mastodon Minstrels toured England in 1884 'in which there were nearly 60 performers... many of them banjoists - line upon line rising in tiers....'. The musicians accompanied 'a score of glittering and airy apparitions, who appeared in shiny mail to go through a silver combat clog dance'. The banjo players included E M Hall, a thimble style player who had worked with Horace Weston. Banjo players in shows like the Haverley's used a variety of styles from thimble playing (frailing) to finger style.

The Bohee Brothers played in both styles. According to W M Brewer (in BMG June 1952 p220) they played thimble style on metal rim banjos, and finger style on wood rim ones. Brewer says that, before their arrival in England, the Bohees had run a concert saloon in Washington Street, Boston, USA, where they played with piano accompaniments .

According to Willoughby Maycock, in BMG (Dec 1903) the arrival of the Bohee Brothers 'marked a distinct epoch'. Their show visited the Theatre Royal Bristol in 1888. A report in the Bristol Times and Mirror on 20th November 1888 said:

Readers of newspapers, and particularly of society journals, will remember that some time ago there was much discussion about the merits of the banjo as a drawing room instrument, and many illustrations were given in the comic serials of the effect its introduction into society could, would, and should produce. Well, with such performers as the Bohee Brothers (from whose entertainment there is an entire absence of everything unseemly) the banjo would not be out of place at social gatherings at the West-end, and indeed so long as the novelty lasted it would be a welcome change at those assemblies where the difficulty is to find something new... Their playing of the instrument which they have made their study was the most perfect ever ...to remember, and there was a considerable amount of artistic excellence about their manipulation.... A medley of popular airs and particularly The Boulanger March were ample to display their marvellous skill... and brought forth ringing cheers ... the Bohee Brothers and their company should not be missed by Bristolians... (K Barker : Theatre Royal collection)

According to Mike Redman of Yatton, the Bohee brothers met twin banjo players George and Edward Craddy in Bristol in the 1890s. Edward Craddy was the father of Horace and Wilfred Craddy, who were older contemporaries of Ray Andrews.

The Bohee Brothers set up a banjo teaching studio in London, and gave lessons to the Prince of Wales. They taught many players who were early members of the banjo club network in London in the 1890s. According to Maycock, James Bohee played an American fretless banjo made by Hammig of New York. The brothers imported banjos from the USA. Maycock writes ' I remember a consignment of beautiful specimens from Stewart of Philadelphia at ... (their) studio in Coventry Street that made my mouth water'

Later the Bohees played British Weaver banjos. 'Stewart' was Samuel Swain Stewart (1855-1898) a banjo and guitar maker, composer, arranger, and publisher He started S S Stewart's Banjo and Guitar Journal from 1888. He published European dance music such as polkas, schottisches, waltzes,mazurkas and classical arrangements . (Ragtime: Its History, Composers and Music, ed J E Hasse, London, 1985; article by Lowell H Shreyer; The Banjo in Ragtime). Stewart's journal was the forerunner of similar publications in England in the 1890s, and his interest in the banjo as a 'classic' instrument was a parallel to that in Britain.

James Bohee died of pneumonia in the County Hotel Ebbw Vale, during a tour in December 1897 aged 53 . His death certificate described him as a 'travelling minstrel' .Younger brother George survived at least until 1926, after a solo singing career in music hall (Brewer BMG June 1952).

The 'organised' banjo tradition

By the late 1880s in England the banjo was a fashionable instrument, almost rivalling the piano. In 1888, Brooklyn-born banjo player Alfred D Cammeyer (1862-1949) arrived in England. Cammeyer invented the closed back zither banjo which lent itself to a less robust style more suited to classical arrangements. As J Rutkowski's US banjo web site says 'His compositions have a refined quality... featuring long lyrical phrases'.

From 1893 tp 1900 Cammeyer was in partnership with Clifford Essex, an English player and banjo maker . Essex had been a professional player for several years, having been a Rugby School-educated solicitor in the City of London. He formed a team of Pierrots who performed at seaside shows. They also performed at the Henley Regatta in 1891 and at Cowes Regatta before the Prince of Wales. At one seaside venue in the south of England, he recruited a young player, Joe Morley, for his Pierrots. Morley had been a member of the Moore and Burgess Minstrels. He went on to become probably the most important and prolific English classic banjo composer.

Essex, an astute businessman, quickly saw the commercial possibilities of the instrument and within a short time was teaching, publishing music, making and selling banjos, and organising concerts. Essex and Cammeyer set up a Banjo Guitar and Mandolin Orchestra in London. Such ensembles became very popular and many such groups existed until recently in many parts of England. In November 1893 they started a magazine Banjo World. After his split with Essex in 1900, Cammeyer bought the title, and in 1903 Essex produced a 'rival', the first BMG magazine.

Another dealer, John Alvey Turner, published his own magazine, Keynotes. These magazines were the 'cement' of the growing banjo, mandolin, and guitar club movement. They gave lists of teachers, tips on playing, advertised instruments, reported local club activities and performances, and published tunes. Many of the compositions which became standard repertoire in classic banjo were first published in Banjo World, BMG, and Keynotes.

The first issue of Banjo World gives an insight into the class and social context of classic banjo music in 1893, as well as its bias towards the activities of the proprietors. A report of a London Cammeyer concert on May 11th 1893 was quoted from the Piccadilly Magazine. Piccadilly described Cammeyer as 'the Paderewski of the banjo ...'. He was accompanied on the piano, and played selections from Cavalliera Rusticana. Banjo compositions of the time often included piano accompaniment. A 30 piece banjo mandolin and guitar orchestra also performed at the concert. The magazine reported that Essex had organised an Officer's Banjo Band at Aldershot, and there was an article by St John Shadwell on 'Our Regimental Banjo Band'. A further article referred with disdain to 'burnt cork' minstrel players and the 'vulgar types of comic song' associated with ' the old tub banjo... an apology for an instrument'. The list of teachers in the first issue of Banjo World included 8 in London and others in Nottingham, Manchester, Preston, Stockton, Liverpool, Macclesfield,Leeds and Dundalk.

Over the next few years, the banjo 'industry' grew across the UK. There were several British manufacturers, including Weaver in London, and Windsor in Birmingham.

Minstrel shows and popular music

Alongside its new 'drawing room' status, the banjo remained an important feature of popular music from the late 19th century. James Bland (born 1854) was a black American songwriter and banjo player who had toured with the Haverley Minstrels. He was described as 'the idol of the halls', and also played in concert halls, clubs and restaurants (see Hamm op cit and M Pickering's A Jet Ornament in Society in Black Music in Britain, ed Paul Oliver, Open Univ Press, 1990). He was said to have written over 600 songs, many of which, like O Dem Golden Slippers entered oral tradition. Ray Andrews' cousins knew their own version of the song. Music halls at the turn of the century often featured black faced singers like Eugene Stratton and G H Elliott. Later, Al Jolson songs entered popular oral tradition. Ray Andrews' repertoire list included Jolson songs for 'singalongs' in pubs. Such black faced minstrel singers remained, of course, a popular and unquestioned form of entertainment until relatively recently.

American influence : recordings, cakewalk and ragtime 1890-1905

Lowell Shreyer's article in Ragtime (op cit) refers to developments in the United States following S S Stewart's promotion of the 'classic' banjo.

Many banjo guitar and mandolin clubs were set up in a number of towns and colleges. They played European as well as American-style music. Publishers like Frederick Allen 'Kerry' Mills wrote, arranged and published schottisches, two-steps and waltzes. He wrote and published the well known two-step march Whistling Rufus in 1897; it was written in over 20 different arrangements for piano, mandolin, guitar, banjo,and one for violin. Mills also wrote Redwing.

In 1893 Sylvester 'Vess' Ossman (1868-1923) recorded the Souza march Washington Post on wax cylinder. He travelled to England in 1900 and 1903, and was said to have influenced Joe Morley and another Essex pierrot player, the young Charlie Rogers. Seven Ossman tunes were published by Clifford Essex in 1903, many of them influenced by ragtime and the cakewalk. Essex's BMG magazine No 1 (October 1903) featured an article about Ossman.

The cakewalk dance had become a fad in the late 1890s. At the newly opened People's Palace music hall in Bristol, for example, on December 5th 1908, Albert Atlas and Lizzie Collins performed 'their American cakewalk, one of the quaintest things seen in recent years'. American banjo players Cadwallader Mays (1873-1903) and Parke Hunter (1876-1912) toured England in 1897, and according to Richard Ineson of Sheffield they played in a Bristol music hall in about 1902. The records of a Vess Ossman associate, Fred van Eps, were also available at the turn of the 20th century.

Banjo Composers

Ray Andrews' repertoire was probably typical of many players who were involved in the classic banjo world and members of a BMG club. The English composers on his tune list include:

- Joe Morley 1861-1937, who was a protege of Clifford Essex from about 1891.Born in Meriden,Warwickshire, he became like his father a boxer in prize fighting tents at the seaside. Morley senior played banjo as a minstrel on the streets, and his son Joe played later in Moore and Burgess's minstrels. He was said to have been 'discovered' by Essex whilst busking at the seaside. Essex then recruited him for his Pierrots. According to an article by Michael Kretzmer in the Birmingham Evening Telegraph (24th June 1983) the reason that Morley was such a prolific tune writer was in order to pay for his betting on racehorses. According to Mike Redman, one of his tunes, Zarana, was named after a racehorse. Clifford Essex published Morley's tunes, but he was said to have received little in the way of royalties. He made only one recording. BBC Radio 4 broadcast a biography of Morley, presented by Gwyn Richards on 28th June 1983. Morley was buried in an unmarked grave in

Streatham, London. In September 2001,several banjo enthusiasts clubbed together to place a named headstone to his grave.

- Emile Grimshaw 1880-1943, who was a stalwart of the BMG movement, and one-time editor of BMG magazine. He published a banjo tutor,and his tunes, like Humouresque, often have an Edwardian 'parlour' quality.

- Olly Oakley who recorded dozens of 78 rpm records in the 1920s and 1930s. Herbert J Ellis who was one of the most prolific earlier banjo composers, often with piano accompaniment.

Also on the list are Alfred Davies Cammeyer (USA) 1862-1949, Kerry Mills (USA), Sam Payne, Arthur Tilley, A Nassau- Kennedy (Canadian), Clifford Essex (as arranger), Albert P Monk, Frank Lawes (1895-1949), Sanders Papworth, A V Middleton, M Rossiter, F Hinds, Abe Holzman, Arthur Stanley, and F.Dorward.

Ray also had copies of music written by F Cecil Folkestone, Ezra Read (a US cakewalk composer), and Scott Joplin.

Other English classic banjo composers were Sydney E Turner, who once visited Bath, Charles Skinner, Norton Greenop (1868- 1930) Alfred Kirby (1876-1949) and from Cornwall, Joe George, who taught the late Tom Barriball, of Bob Cann's Dartmoor Pixie Band. Barriball was the teacher of Rob Murch, who Musical Traditions readers will know from his work with the Pixie Band and on the recent Mark Bazeley and Jason Rice CD on the Veteran label. One of George's tunes was The Kissing Cup Waltz.

Other American classic composers were Alfred Farland (1864-1954),George Gregory, and Paul Eno (1869-1924), who with Horace Weston, were encouraged by S S Stewart . Gregory's music was published in the UK by Essex.

The transatlantic links in the music are illustrated by a note on the American Banjo Federation's web site. The tune Sunflower Dance was originally a Herman Rowland tune With the Tide Schottische, published by S S Stewart in 1886. It was recorded by Vess Ossman, and published by Clifford Essex in England under the new title. It then appeared in this version in Emile Grimshaw's banjo tutor.

The banjo in the South West

By 1895, Banjo World was listing teachers in Exeter (Harry Angel) and Torquay, and banjo activity in Plymouth, Yeovil, Bath and Bristol. Angel reported from North Tawton - ' Pupils here are getting on remarkably well ...' (Banjo World op cit p58). In the same issue, J E Allen, a local banjo teacher, reported a concert by the nine-piece Stroud Banjo Band, and mentioned a young player 'Master Owen Johnson'. In August 1895, the magazine included a report form Yeovil which referred to a Kipling poem The Song of the Banjo. The writer says 'he calls it the ''wardrum of the English around the world'''.

W H Pettit reported from Bristol - 'the banjo is very popular down here. Several of my pupils have played at concerts, bazaars ... quite recently and in most cases have acquitted themselves creditably. One young lady played in the Clifton Pompadour Band and was encored for each piece' (Banjo World May- June 1895 p57).

Will Pettit and the Craddy family

Will Pettit taught George and Edward Craddy in Bristol from 1895. In BMG (March 1970) R Tarrant Bailey says they performed as the Craddy Brothers Twins, playing zither banjo duets. Edward Craddy's sons Wilfred and Horace became well known players. Wilfred played piano accompaniment to his brother's finger style banjo. As a boy Horace won the Gold Medal in a national competition; he later played in the John Birmingham orchestra, made radio broadcasts, and played in Kentucky minstrel shows in Bristol. From the 1920s he switched mainly to plectrum banjo, following a trend brought about by jazz and dance bands. By then, the 5 string banjo had become less common in 'commercial' popular music. According to Mike Redman, Horace Craddy ordered a tenor banjo from America, and it arrived by horse and carriage wrapped in velvet, with a metal zip.

By 1929, there was a Craddy Music shop in Gloucester Road Bristol (BMG 1928-9) and Horace Craddy was teaching 5 string and tenor banjo at Whitehall, East Bristol. He taught tenor banjo and guitar to many musicians who went on to play in local jazz and dance bands. The Craddy brothers themselves played in a dance band with another tenor player, Gordon Dando. Their band was based at Packer's sweet factory in Whitehall where Horace was a salesman. It was at the Packer's Hall that Ray Andrews had heard zither banjo player and composer, Olly Oakley perform in the late 1930s.

BMG clubs in the Bristol area between the Wars

After the First World War R Tarrant Bailey formed a BMG club in Bath in 1924. The Weston BMG club was set up at about the same time. It was not until 1928 that a 'modern' BMG club was formed in Bristol.In 1927, Alf North, who had moved from Worcester, advertised in the Bristol Evening Times and Echo for banjo players who wished to form a club (letter, William J Ball to Norman Sharp 1997). North had been a player since 1889 (BMG article by F Shewring Feb 1923) and was familiar with the work of Cammeyer, Morley and others. Bristol BMG rapidly grew from 9 members at its first meeting to 30 within a couple of months (Keynotes May 1928).

The repertoire of the club was already fairly standardised, and included Payne's White Coons, also played at other clubs. Ray Andrews often played this tune, probably learnt from Harold Sharp. At a public concert in Totterdown YMCA hall, in Bristol in October 1928, the performance by club members included 3 tunes by Grimshaw and one by Cammeyer that were in Ray Andrews' 1970s-80s repertoire.

The club met in various venues, from a room over a store in Clifton, to the Clifton Arts Centre in Charlotte Street, and then at the Swan pub in Stokes Croft. Regular reports were sent to BMG and Keynotes while Alf North was secretary, but they tailed off after he emigrated to Christchurch, New Zealand in 1929. He died there in December 1930. A new secretary, D Milligan, had taken over, and according to Bill Ball, the club folded for a while. A new East Bristol club was apparently formed in the 1930s and lasted for some years.

Away from the BMG club scene, the plectrum tenor banjo was probably holding sway over the 5 string finger style. As well as Horace Craddy, Lou Carson taught banjo in Bishopston,Bristol, where Bob Riddeford's cousin and brother had lessons in 1936-7. In Weston, Alf Brimble, still playing today, learnt the banjo as a boy and played in concert parties aged 11 in 1928, although he was not a member of the local BMG group.

Bristol BMG club after 1945

Like many others,the Bristol BMG club reformed after the Second World War. According to John Hopes, at its peak in the 1950s, the band was up to 50 strong.

The club won many national competitions, and played concerts at many local functions. Ray Andrews often organised these events. Inevitably, with a different musical environment, the club weakened. By the 1960s, members wished to change the repertoire from the earlier 20th century material, and the club began to include more contemporary popular arrangements.  Membership fell and became increasingly older. In the 1970s the club folded, but eventually the Fingers and Frets club established itself as a replacement.

Membership fell and became increasingly older. In the 1970s the club folded, but eventually the Fingers and Frets club established itself as a replacement.