Article MT258

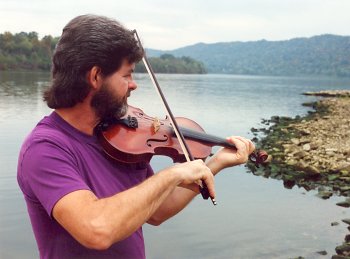

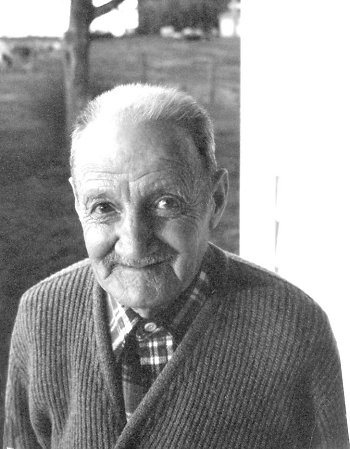

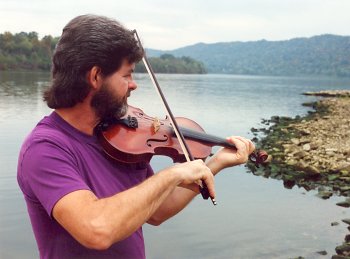

Roger Cooper

1995 Autobiographical Statement

from Rounder 0380, Going Back to Old Kentucky

prepared by Mark Wilson

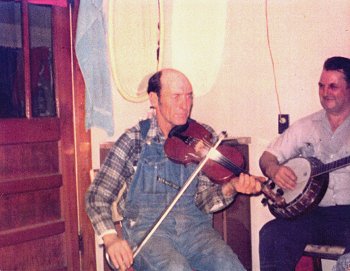

The first time that I really had a taste of good fiddling was over at Bob Prater's, out Foxport way. My uncle Gene took me up there when I was about twelve years old. Bob died here a few months ago after being sick for a long time, but back in those days - 1960 or around then - he was really a tough man. He farmed and built barns and houses - Lord, he just worked all the time. I don't see how he could get his fingers to work on the fiddle, because he farmed so hard. But they did, though - those fingers always worked real good. Bob had a rhythm that was just about unique to most any fiddler I've heard. Just a good dance rhythm, but it'd put a mark on you after you'd heard him play. It really excited me, I'll tell you. I decided right then that I wanted to be a fiddler, though I didn't know how to get to be one. I thought to myself, "Yeah, that's where it's at - what a guy needs to play is the fiddle." Of course, Bob also had some nice-looking daughters about my age, so I liked to go over there for that, too.

A whole lot of musicians would come over to Bob's. Pretty soon somebody'd holler to get Bob's brother Bill. Usually there'd be Shirley Cline and Brooks Mineer over too. They've all got that same lick out through there, Bob and Bill and Brooks, they all got that same rhythm about the way that they play. Bob learned tunes from his dad and from them Rolphs over around Burtonville. They were good strong fiddlers when Bob was growing up, so maybe Bob got some of his style off of them. I used to see Bob's daddy over there when I was a kid. He was about ninety years old but he'd always play a few tunes.

A whole lot of musicians would come over to Bob's. Pretty soon somebody'd holler to get Bob's brother Bill. Usually there'd be Shirley Cline and Brooks Mineer over too. They've all got that same lick out through there, Bob and Bill and Brooks, they all got that same rhythm about the way that they play. Bob learned tunes from his dad and from them Rolphs over around Burtonville. They were good strong fiddlers when Bob was growing up, so maybe Bob got some of his style off of them. I used to see Bob's daddy over there when I was a kid. He was about ninety years old but he'd always play a few tunes.

Since then I've thought a lot about timing in a fiddle tune and how Bob done it. The older time players had a little different approach on the way they'd put in the chord changes. They'd sometimes shave the corners off the timing, where nowadays fiddlers put more timing in, squaring it up like four lines, you know. Well, the old timers put four lines in, but they'd phrase it in such a way that some of the timing would get shaved off at the edges just where they d go right on to the next part. Some way or another they was getting to that next space sooner. It's just an old-time approach - Doc Roberts did it and Clark Kessinger done that some, too. When they was a-doing that, there was no need for them to wait for the timing to come back around. Nowadays the biggest percentage of fiddlers will just the same as stop when they get to the end of eight bars or just drag it out with what they call 'time licks'. But those old timers never did lose time or nothing; it's really all in there, but it just seems a little odd according to the way people think about music today. I really like that old time kind of timing and use some of it my own self, although it feels a little funny to me until I play it awhile. But once you get used to it, it'll sound wrong if you don't time it like that.

Maybe that's why Bob's rhythm was so good, because he'd shave them corners off and be already there to start on the next part. In the old days too, the guitar players would hit just right down across a chord with just one big rake. Somehow or another they would come out with a beat and a half out of this deal and that would put the fiddler right on the side of the beat where they has all the drive and then the melody would just float right along over that. So rhythm's where it's at with a fiddle tune: it's not so much what you're putting in there that makes a dandy tune as what you leave out.

Bob played for a dance just about every week or two somewhere around Maysville, Owingsville, Flemingsburg or Vanceburg. The banjo player, Arthur Breaze, would hunt down places for them to play - Bob probably wouldn't have fooled with it himself. Bob once told me about one time he was supposed to play over at Portsmouth. When he opened up his fiddle case that morning, he found that the neck had come unglued and his fiddle was laying there in pieces. And he had to play that night. So he hollered for the old woman to come in there and get some of that super glue. They tried to hold the fiddle together until the glue'd dry but Bob got some of it on his fingers and he couldn't get loose of the fiddle. So he really went into a panic and wrestled around with that fiddle. Finally he got her unhooked, but two of his fingers were stuck together. Bob said he had a terrible time of it, with that glue all over him, but he somehow got over there to play that night.

Bob talked like somebody from back in another time and always had a bunch of old sayings. He was funny about fiddling and always acted like he didn't care about it. I'd go over and ask, "Bob, you want to play a tune?" and he d say, "Oh, my, I can't play no fiddle - I don't even like fiddle music. Then he'd say, "Why, I ain't played a tune in two years." "But, Bob," I'd say, "I knowed you played a dance with Arthur Breaze just two nights ago." "Oh, that," he'd say, "there was a mess of fiddling over there and I got into playing with Arthur and, what a mess, I couldn't get out of it." And he'd go on and on that way - I always thought it was funny. Of course, by the time you'd be ready to go, Bob would be all wound up: "Oh, no, no, stay; let's play another one before you go." I've always thought that probably Bob worked so hard that he didn't think about the fiddle a lot of the time, but when he got one in his hand, he'd really get back into it.

This habit of Bob's aggravated Buddy Thomas so much that one day he said to me, "We'll just fix Bob of that." So Budd picked me out four or five tunes and planned it all out. He told me, "We'll go down there and first you play these tunes right here. Then hand me the fiddle and I'll be all over him with some of my good stuff. By that time, Bob'll be all wound up and dying to play himself. Then we just get up casual like and leave him there a-hanging." And it all happened just as Buddy said it would and Buddy would laugh about it for days after. It's funny to put that much work into pulling a prank, but that's just the way Budd was.

This habit of Bob's aggravated Buddy Thomas so much that one day he said to me, "We'll just fix Bob of that." So Budd picked me out four or five tunes and planned it all out. He told me, "We'll go down there and first you play these tunes right here. Then hand me the fiddle and I'll be all over him with some of my good stuff. By that time, Bob'll be all wound up and dying to play himself. Then we just get up casual like and leave him there a-hanging." And it all happened just as Buddy said it would and Buddy would laugh about it for days after. It's funny to put that much work into pulling a prank, but that's just the way Budd was.

The first time I ever did see Buddy, I was probably about eight years old and he was playing at a grocery store down around Vanceburg where I was raised. They had a mobile unit in a little old trailer and they'd just set up the microphones and do a show right there in the store as an advertisement. I probably didn't see him again for a few years after. But before I get onto talking about Buddy, let me tell you about Uncle Joe. Now my family lived all sorts of different places but all of it right within Lewis County. One time we lived back across the creek from a little bitty radio station where Uncle Joe Stamper ran a music show. Uncle Joe was a great guy. He was then in his seventies and played the fiddle and the banjo, but he didn't do any singing. That show was a big deal to him. He'd drive in there in an old '53 Chevrolet and boy, he'd be dressed up, with his hair all combed real pretty. He'd unlock the trunk and get the fiddle and banjo out. He acted just like a big star and I'm sure in his own mind he was. A lot of people I knew listened to him but sometimes Joe'd have a little trouble with the radio station talking about canceling his show. Joe worried a lot about that, so at the end of every show, he'd tell the listeners out there to send the cards and letters in to let the station know how much they liked the show. Buddy told me that a lot of times Joe would write his own letters in to himself just to make the station think that people was still interested. In any case, I started fooling with the guitar when I was about eight or nine years old. A lot of times Joe couldn't get much help to come in and play, so he'd ask me down to play backup or pick a tune like Wildwood Flower. I remember one time I was down there and the only people in the studio were Joe and myself and a family from Carter County. But Joe let on like there was a big crowd in there. He'd announce on the microphone, "Yes sir, we've got a whole studio full of musicians here today." He'd call the girl in that family up to sing a song and he'd introduce her as Sheila. But the next time around, maybe he'd introduce her a different way, "Now, here's little Shirley coming up to give us a song."

Sometimes Uncle Joe would have good fiddlers in there to play like Jimmy Wheeler and Henry York. One time when I was a kid, Jimmy Wheeler was playing a tune and really started getting into it. Jimmy had closed his eyes while playing but Uncle Joe had to go to a commercial break. So Uncle Joe just went ahead to the commercial and then switched back to the studio, with Jimmy not a-noticing and still a-playing that same tune. Well, Buddy was a real good friend of Uncle Joe's so he'd come in there sometimes and I'd see Budd down at the radio station. I was starting to mess around on the fiddle, but I wouldn't say much to Budd because he was such a good player and I was just a beginner.

But a few years later after I got my driver's license, I went out and hunted him up. Somebody told me he was staying out with Uncle Joe, who lived up Kinney about six miles. So about two o'clock in the afternoon me and old Bunk Meadows went out there and knocked on the door and Buddy's mom answered it.

We asked, "Is Uncle Joe here?"

"Yeah."

"Is Buddy here, too?"

"They're both in there in the bed. They ain't never got up yet." Well, we went in and there they laid - so busy talking about fishing and fiddling and stuff that they had never gotten up. But after we came in, they got dressed and, boy, we played some real music after that.

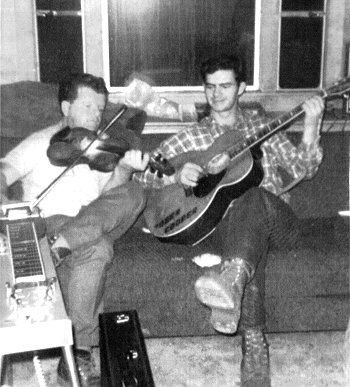

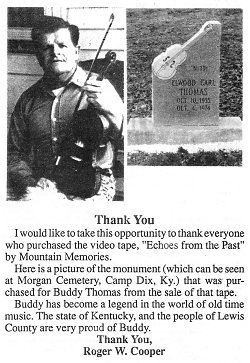

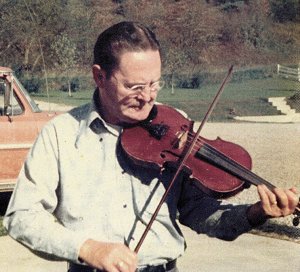

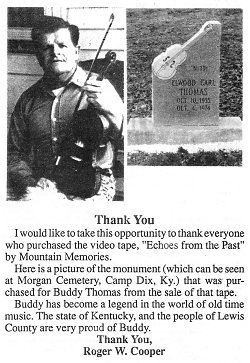

Ever since Buddy's been my main man in music. I just liked his playing better than anything else I've ever heard and when I try to work up a fiddle tune, I always try to think on how Buddy would have done it. And he was so enjoyable to be around, with all of his jokes a-going and his carrying on all the time. I had the most fun that I ever had in my life when I was around Budd. He'll be dead twenty three years come this fall and I still think about him and his music most nearly every day.

Ever since Buddy's been my main man in music. I just liked his playing better than anything else I've ever heard and when I try to work up a fiddle tune, I always try to think on how Buddy would have done it. And he was so enjoyable to be around, with all of his jokes a-going and his carrying on all the time. I had the most fun that I ever had in my life when I was around Budd. He'll be dead twenty three years come this fall and I still think about him and his music most nearly every day.

Old Budd grew up right close to his mother. She really came from another time, with her old time ways and everything. You might just say she was way behind the times in the world. And Budd liked being back there in that old world somewhere too, so that you might say he kind of lived in two different worlds. Budd was never a guy for schedules or anything like that; he would just try to find a way to have fun no matter what. That was pretty much the way it was with all of them old-time country people and Budd couldn't really understand the way of the modern world like all of us, I guess. So if things got too aggravating, he'll just go off in that old time world somewheres.

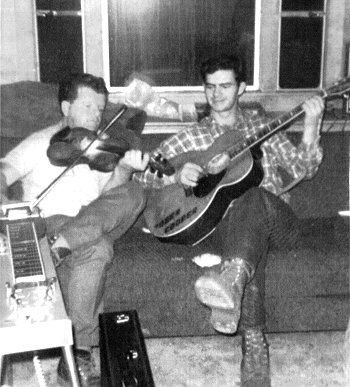

I really got to know Buddy when I was working up in Bucyrus, Ohio in a factory. Budd's brother-in-law, Leona's husband, lived up there too and Buddy just decided to come hang around up there. When I heard that he was up there, heck, I went over that same night. Buddy like to have somebody around who was interested in what he was doing and I was the most interested person in the world. Well, Budd just loved to get in the car and go off somewheres to play music. I had a car, so we'd go down to them bars or a VFW and we would get around them bluegrass players. There was so many bluegrass players around that community up there and everybody knowed everyone else that played bluegrass. Well, all of them bluegrass players latched right on to Budd. They didn't really need another guitar player, but I'd play upright bass with them. Back then you could make twenty dollars a night playing bluegrass and if you played country, you could make about twenty-five. That kept Budd a-going for a long time. He knew how to play every bit of all the bluegrass stuff. He'd do all the bluegrass instrumentals - Cheyenne, Crossing the Big Sandy, Panhandle Country, Me and My Fiddle - all that stuff. He could copy any break that Benny Martin ever took. He could take an old-time tune like Portsmouth Airs and make a great bluegrass instrumental out of that. He played all that stuff real pretty and put the fire in them, too. He was courteous in his backup too and could make any singer sound good with that fiddle, whether it was country music or bluegrass.

Finally a banjo player got him a job at Swan Rubber that was just suited for Budd. He made $2.09 an hour - probably the most money he ever made in his life. Well, Budd wasn't able to do no work hardly, but all he had to do there was to sit in that little lunchroom and keep it clean. Maybe he had to get up and sweep the floor two or three times a day. Other than that, he just sat in there eight hours every day, drinking coffee and cutting up and carrying on with everybody that would come in there. People just liked to have him around, to cut up and act a fool. With Budd, you'd never run out of jokes and tales. You see, Buddy was just like a cat bird. He could imitate a lot of cartoon characters and about anybody else if he was around them a little bit. If they was the least bit unusual in any way, he'd latch right onto that and he'd just go to exaggerating in every way on that person. And he might carry on two or three days about that person until he'd seen somebody more interesting. He'd carry on all the time like that - just keep you rolling, laughing all the time.

So that lunch room was really a great job for Budd, but he got tired of keeping on schedule after awhile and went back to Kentucky. He'd use his mother as an excuse a lot. "Oh, I've got to stay home with Mommy down there, she's getting old." Well, he wasn't too much help to his mother, because she done more work than he ever did. He was just painting a picture, but I think he just got homesick and tired of having to get up everyday.

So that lunch room was really a great job for Budd, but he got tired of keeping on schedule after awhile and went back to Kentucky. He'd use his mother as an excuse a lot. "Oh, I've got to stay home with Mommy down there, she's getting old." Well, he wasn't too much help to his mother, because she done more work than he ever did. He was just painting a picture, but I think he just got homesick and tired of having to get up everyday.

After that he'd sort of drift back and forth between Ohio and Kentucky. One time me and him had a house out in the country that we heated with coal in a big old stove. There'd been a great big snow. Budd wasn't working anywheres, but I was late getting over to my job at Swan Rubber, "Budd," I said, "I got to get on in there to work. You'll have to get the fire going." He answered, "Yeah, go on." When I got home that evening, boy, was it was cold in there. I got worried: "Buddy!" "Yeah, I'm in here," he called. Well, he was still in the bed. He told me, "I was going to get up and get that fire going, but it's just so cold, I couldn't get out from under the covers." It's a wonder he didn't freeze to death.

He was so slow about doing things, it'd take him forever to do anything. He'd go to shave and it'd take him a good hour, by the time he got the water heated up and this and that. And, of course, the lather had to be just right. He had a old tape recorder, and he couldn't hardly shave for listening to it. He'd start to shave but then he'd stop to listen and back the tape up to hear some fiddle tune again. Next thing you know, his lather would be all dry, and he'd have to start that process all over again. His mind would stop on fiddling or something, and there he'd be. He'd stick right there until somebody bothered him and got him off of that. But all the time, no matter where he was, if he wasn't a-talking or laughing, he'd be humming a fiddle tune in his mind or whistling a little bit of it. But there wasn't any point in him being in any hurry, because he had nowhere to go.

One time he decided to go back home and try his hand at farming. I hadn't seen Buddy for a while, so when I came down to Kentucky, I went out to his house. When I topped that big old hill, first thing I saw was Budd's horse standing in the middle of the barn, looking so poorly that he was leaning against the center post in the barn to stand up. I knocked on the door and Buddy says, "Come in." Him and his mom was stripping tobacco right there in the living room of the house. It was the sorriest looking crop I ever did see. I asked, "Well, Buddy, were you wanting to play some?" He said, "Well, I got to get this tobacco stripped, no doubt about it." I said, "Well, you fiddle and I'll strip your tobacco." Okay, he was glad to have me do that. He got to fiddling and had his niece, Leona's little girl, a-dancing. After a while, I mentioned to Buddy, "I wouldn't want to make you mad, but this is about the sorriest looking crop of tobacco I ever did see." "I know," Budd replied, "but it ain't because of the way I farm. You see the ground's so poor up here, full of clay and stuff, that you'd have to sit down on a sack of fertilizer to raise an umbrella."

Up in Ohio he tried real hard to teach me the fiddle. Sometimes I'd sit there in a chair beside of him, and I'd bow the fiddle and he would note it, or I'd note it and he'd bow it. Sometimes he'd stand right behind me and reach down and put his hand on the back of mine and make me relax my hand and wrist, and then he'd just work my hand for me. Whatever he was wanting me to play, he'd just get my hand started in rhythm, and then he'd let me loose, just like somebody teaching you to ride a bicycle. He told me, "When you're trying to learn a new tune, go ahead and run all the way through the parts: don't stop and try to get a piece just right. Just go on through, and if you don't get it the first time, try for it the next time around. That'll keep the feel of the tune the way it should be. You'll eventually get it - just keep going after it."

He used to talk about the different ways of bowing. It was almost too much for me to understand, for he was talking over my head most of the time. He'd talk about making the bow dance across the strings. "And then," he'd say, "You've got to make your fingers dance at the same time too. They're partners." He'd talk about how the bow and the fingers work together and he would lift his bow off the fiddle and go on noting, and you could hear his fingers pounding on the strings, just like they was a-dancing. A lot of times he'd be trying to learn a tune and have a fiddle in his hand and he'd just be scratching along. It'd sound pretty bad for a while, but when he got it figured out, he'd decide to put the pressure on, and it'd be beautiful then. I tell you, old Budd was magic.

Sometimes in a tune you'll get to a certain part where you'll realize your bow is in an awkward place for you. In order to get the tune to come out, you'll have to bow backwards for a ways until you get to another spot where the bow will turn back the right way for you. A lot of fiddlers will stop and restart the bow when they get to one of those places, to keep the bow movement going forward all the time, but Buddy always said that you had to learn how to keep that bow going when it turns over for you and you find yourself going backwards. Learn to play it that way because there'll be many times you'll have to play coming and going both. I've found what Buddy told me to be true many times, although it's a little awkward until you get used to it. Another master of the bow I knew, George Hawkins, would bow a difficult tune like Martha Campbell forwards and then, just to show you how he could use the bow, he would play it all the way through with the bow a-going backwards. He was so good that, if you didn't pay careful attention, you'd never know which way he was going with it.

Sometimes in a tune you'll get to a certain part where you'll realize your bow is in an awkward place for you. In order to get the tune to come out, you'll have to bow backwards for a ways until you get to another spot where the bow will turn back the right way for you. A lot of fiddlers will stop and restart the bow when they get to one of those places, to keep the bow movement going forward all the time, but Buddy always said that you had to learn how to keep that bow going when it turns over for you and you find yourself going backwards. Learn to play it that way because there'll be many times you'll have to play coming and going both. I've found what Buddy told me to be true many times, although it's a little awkward until you get used to it. Another master of the bow I knew, George Hawkins, would bow a difficult tune like Martha Campbell forwards and then, just to show you how he could use the bow, he would play it all the way through with the bow a-going backwards. He was so good that, if you didn't pay careful attention, you'd never know which way he was going with it.

One of the main things Budd told me about old time music is to watch where the beat is. Most people today like to play right in the pocket of the beat, but some of the old timers would play just ahead of it, a little bit on one side of the beat. That gives an awful pretty effect and keeps the drive up in a tune. But you can also play on the back side of the beat on some things. There's so many different ways to go about playing a fiddle tune, which are all good so long as you keep the melody original.

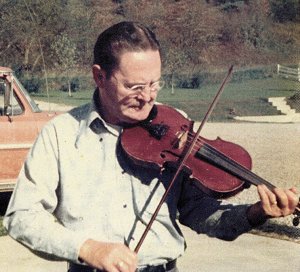

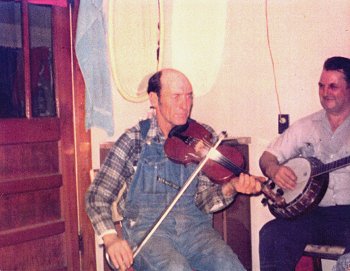

Now Buddy could play a lot of different kinds of fiddle. He could play bluegrass and country, but most of all he liked those old time fiddle tunes because they were lonesomer. He could play real old-time fiddle like his cousin Perry Riley and he could play Morris Allen and Acey Neil style too. And he'd blend all of that together and I can hear lots of a Paul Warren flavor in his playing as well. He might learn something like Dance All Night with a Bottle in Your Hand from Clayton McMichen who was living up here, but he wouldn't play it like Clayton, but more like Paul Warren. And he'd treat Jimmy Wheeler's tunes the same way. If he learned a tune from Jimmy, it wouldn't come out sounding like Jimmy at all, but it'd be more lonesome and have a lot more rhythm in the bow. Jimmy always played on single strings, but when Buddy put his own style on it, he used a lot more double notes and that gave it a fatter sound. Sometimes Jimmy would try to put a lot of fancy stuff in his fiddling, but Buddy thought that was hot-dogging and would leave it out. He'd work real hard at putting a fiddle tune together, with all sorts of little changes and complicated bowing. Sometimes I hear people who think they've learned one of Buddy's tunes by just catching the main melody or something, but they're just scratching the surface. To really learn a Buddy Thomas tune, you've got your work cut out for you.

People talk about 'Lewis County fiddling' now, but what I think they really mean is Buddy Thomas style and it was just something he had developed his own self from everybody else's playing that he had ever heard. Budd would work real hard on his fiddle tunes and I noticed that he would fool with timing a whole lot. When he attacked a new part, he might almost wait too long sometimes, and then come right back at the last split second. To me it felt like Budd was bending that timing just a little bit without actually losing it. When it all came out, he stayed right in there, and those hesitations gave a real nice effect to the tune. I like to work on those kind of things in my own playing.

Back in them days, if Buddy'd hear of a fiddler anywhere, he'd try to find out all he could about them and track them down. He knew just about everybody out here in Lewis County and spent a lot of time around Portsmouth and Maysville and up in Carter and Lewis Counties. Way back a whole bunch of fiddlers left out of here on account of work and went to Cincinnati and places like that. Buddy one time moved over to Adams County, Ohio and stayed there close to a year and met a bunch of these fiddlers up there. So I always enjoying driving around with Buddy to meet these different fiddlers.

A lot of these old time fiddlers around here were good friends, but yet there was a lot of competition involved about fiddling, too. Buddy liked to go around all them guys and he learned quite a few tunes off of them. There was a flock of good fiddlers around Portsmouth. Asa Neil always had the name of the biggest fiddler around there. He came from Lewis County and grew up on a shantyboat on the river. They'd just live in them and if they wanted to move, they'd just float on down the river. Acey married a woman that lived out by Bob Prater, so your fiddlers back in there knew who he was. Even the Flemingsburg fiddlers got to know him because them old guys would talk about hearing Acey play on the radio over there. Buddy always called Acey a top-cat fiddler and said he was always real nice when he wasn't around fiddling. But he said Acey was stingy about his fiddling and would get competitive and say harsh things. Before a fiddle contest, Acey might say in a loud voice so that Budd could hear him, "Well, I'm the better fiddler, but they'll just let somebody like Buddy Thomas win it." Which Buddy told me he then did.

Anyways, fiddlers were always saying things about one another like that and Budd could aggravate them the same way right back, too. Now I've only heard Acey on tapes, but I think he was a real good fiddle player, although he'd get a little bit flashy sometimes. I can hear some of the same licks in his playing that I hear in those Ed Haley records. I'm probably prejudiced, but, to my way of thinking, Buddy was way ahead of Acey and any of them other fiddlers on old time tunes. Morris Allen told me that Acey Neil wanted to beat Clark Kessinger so bad that he burnt hundreds of dollars worth of kerosene setting up at night practicing Ragtime Annie to beat Clark Kessinger. Clark would bum a ride down to Portsmouth and play ever so often. Morris remembered seeing Clark sitting on the back of the truck a-cussing as it drove out of town - probably lost a fiddle contest, I suppose.

Fiddlers were always funny about losing contests. One time they had a big music contest in Vanceburg on the courthouse steps. A lot of fiddlers and banjo players went to it and Buddy was there too. When he got back home that evening, he ran into the neighbor lady. Mrs Nichols - that was her name - asked, "Buddy, did you go down to the music contest in town?"

He answered, "Yes, Mrs Nichols, I did."

"Well, who won the fiddling contest?"

Budd replied, "I did, Mrs Nichols."

"Well, that's great. I'm glad you won it. What about the banjo contest, who won it?"

"I did, Mrs Nichols."

"Well, you really done good then. Did they have a guitar contest, too?" Budd told her, "Yes."

"Well, who won it?"

"I did, Mrs Nichols."

"Well, that's wonderful, Buddy. You must really be playing good. Who else played in the contest?"

"Just me, Mrs. Nichols." It turned out that though other players were there, they didn't figure they could do any good against Budd. So he just played in all of them and took the money home.

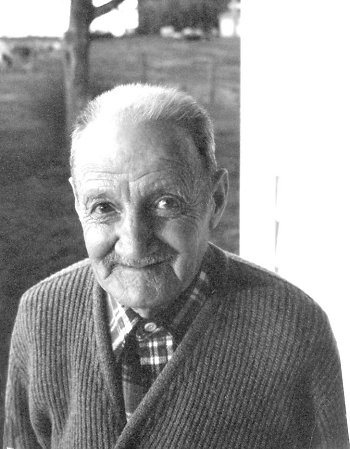

Probably the fiddler from that area that had the biggest influence on Buddy was old man Morris Allen over in South Shore. Budd really liked Morris and his wife Agnes. Morris had been raised by the Keibler family and there were seven fiddle players in that family. They always said that Uncle John Keibler was supposed to have been the best. Morris had really good jobs in the steel mills over at Portsmouth and in New Boston. He was also a big fox hunter. I still remember the first time I went up there with Buddy, Morris was out there doctoring on them dogs. His dogs had some kind of mites, so Morris was blowing some kind of powder in their ears through a straw. Boy, was he a mess when we showed up: he had that powder and tobacco juice all over him and his dogs. But Morris didn't care what anybody thought of him. He'd always speak his mind. Anything that came on his mind, he'd just say it. Oh, he would insult people. He'd hear somebody playing, and if he didn't like the way they played, he'd tell them. He'd say, "Oh, you can't play no fiddle. You're all wrong. You're playing that wrong." He never worried about nobody jumping on him or nothing, because he always had carried a gun in his pocket.

Buddy told me one time that Morris was really burning up Forked Deer, playing the best that Budd had ever heard. All of a sudden Morris stopped and burst out laughing, "I'll give Acey Neil a hundred dollars if he can play Forked Deer that good." Then he went right back to fiddling again.

I tell you, Morris and Agnes were real good people. After Buddy died, I lived for a couple of years up the road just about three miles and would go down to see them a lot. He was pretty old by then, but he helped me a lot in my fiddling. I remember he asked me to play Wagoner one time and, after I had played a little bit of it, he said, "You got your bow lick turned around on it." So he took the fiddle and he was right, too - straightened me right up on it. Morris could play all the standards and then a hundred others that you'd never even heard tell of before, too.  The trouble was that he'd just soon play you a standard as one of the others and as he got older, it'd be hard to get him on other tunes. And Morris was bad about just playing them short and not playing real long, so it was hard to pick those tunes up. But me and Buddy got some of our best tunes from old Morris. His cousin Abe Keibler is another good fiddler and still going strong at eighty-eight; I've picked up a lot from him too.

The trouble was that he'd just soon play you a standard as one of the others and as he got older, it'd be hard to get him on other tunes. And Morris was bad about just playing them short and not playing real long, so it was hard to pick those tunes up. But me and Buddy got some of our best tunes from old Morris. His cousin Abe Keibler is another good fiddler and still going strong at eighty-eight; I've picked up a lot from him too.

Another fiddler over in Portsmouth that me and Buddy both learned some tunes from was Jimmy Wheeler. Everybody talked about him because he was a great instrument repairman, but they never mentioned his fiddling much. But he was real good, though he didn't claim to be no fiddler - he was always talking about Acey Neil or Forrest Pick, who was another Portsmouth fiddler that I saw a couple of times at contests. I never knew of Jimmy being married, but he lived at his shop with his mom, and he had two sisters that lived right next door to him. At different times he would have birds: he had a dove when I first met him and later on it was a blind pigeon. The first time I went up there with Buddy he had a little old dog. That dog would howl along with fiddling. Jimmy would hold his mouth together and try to keep it quiet while Buddy was playing, but he'd still howl through his nose. Finally Jimmy'd get up and put it outside. Jimmy had kind of an odd sense of humor and didn't seem to care nothing about money. One time he filled a bow for me and charged me three dollars. He said, "Just throw the check in that dish there." Every time I'd go back, that check would still be there. I counted one time and that check was still lying there three years later.

Jimmy told me his dad had been a pretty good fiddler and would talk about some of the tunes his dad knew. He said that once a week all the fiddle players in the countryside would go gather around the piano in Portsmouth - this was probably in 1910 or so. They'd get sheet music through the mail and have a piano player to play the music off the paper. The fiddlers would play along with it until they learned the tune. I guess that's how a lot of those tunes got to be around Portsmouth. I think they're cute tunes, but they're a little different from what I'm used to. When Jimmy was younger, he played music full time in the big bands; he played upright bass and rhythm guitar for those kind of things. And he would back up Forrest Pick and Asa Neil on fiddle tunes a lot on the radio, I understand. As I said, Jimmy used to come down to Joe Stamper's radio show when I was a kid.

Buddy told me once that he'd been staying at Morris' house for about a week, just burning the fiddle up a-practicing, when Morris looked out the window and said, "Oh, here's Acey Neil and Jimmy Wheeler coming up in an automobile. Let's hide the fiddles under the bed, Buddy." When they came in, Morris asked, "Did you boys bring your fiddles? We ain't got none here and we're just dying to play some fiddle music." Buddy would always laugh and say that they had edged Acey and Jimmy out that day through being real hot from the start.

Buddy told me once that he'd been staying at Morris' house for about a week, just burning the fiddle up a-practicing, when Morris looked out the window and said, "Oh, here's Acey Neil and Jimmy Wheeler coming up in an automobile. Let's hide the fiddles under the bed, Buddy." When they came in, Morris asked, "Did you boys bring your fiddles? We ain't got none here and we're just dying to play some fiddle music." Buddy would always laugh and say that they had edged Acey and Jimmy out that day through being real hot from the start.

I had never heard anything about Ed Haley until the Rounder record came out, but, once I was aware of him, it turned out that a lot of the older people like Morris and John Lozier knew him. There was a fiddler named Bob Glenn out of West Virginia who would pass through the country traveling and would stay with Morris's uncles, them Keiblers. Now Ed knew Bob Glenn too and one time Uncle John Keibler went to hear Ed Haley play. One of the fellows asked Ed, "Would you care to let this fellow play one on your fiddle?" Ed said, "Go ahead." So Uncle John played one of Bob's tunes and, Ed being blind, couldn't tell who it was. "Are you Glenn? Are you Bob Glenn?" He got all excited and went to feeling Uncle John's face to find out who it was. Morris always thought that was a great compliment for John Keibler.

There was another bunch of good fiddlers right in a pocket out through Bath County and that area: Carlton Rawlings, Henry York, Warner Walton, Alfred Bailey, they were all good fiddlers. One that I got to know pretty good was George Hawkins. Maybe he'd go play two or three sets at a dance with Bob Prater somewhere, but George wasn't really a dance-type player. He knew all these hornpipes and jigs and other things like that and was a really good fiddler. I was always amazed at the tunes that he played. So I'd go over to his house every once in a while and aggravate him to tape tunes and show me stuff. He liked to give you advice to help straighten up your playing. You know I play a little hard. George once told me, "You've got a good bow hand, but you might play a little bit hard. Now I've got one of the best bow hands in the business - so the people tell me." Yeah, old man Hawkins was a character; I really liked him and he sure had some good tunes. Once he and Budd had both been beaten in a fiddle context in Maysville by Clayton McMichen and George was complaining to Budd. Like everybody else, he called Buddy 'Shorty' even though if there was ever anybody in the world shorter than Buddy Thomas, it was George Hawkins. "Now, Shorty," George said,  "you're the best fiddler here - except for me." Buddy laughed and shook his hand, "I believe you're right." Buddy always thought that was real funny, but Buddy had a lot of respect for George and what he knew about the fiddle.

"you're the best fiddler here - except for me." Buddy laughed and shook his hand, "I believe you're right." Buddy always thought that was real funny, but Buddy had a lot of respect for George and what he knew about the fiddle.

Talking about being short, one time I went over to Uncle Joe's house for some fiddling, and when I got there, I noticed a big hole in the door up about six foot high. I asked, "Joe, what happened to your door there?" He answered, "There was somebody out there drunk the other night who tried to break in on me. I called out, 'Who is it?' but they never said nothing, so I just let the gun go off right through the door. I wasn't going to fool with them." A couple of weeks later I run across Buddy and I said, "Buddy, did you see that big hole in Joe Stamper's door where some drunk tried to break in on him. Wonder who'd do something like that?" Budd answered, "Well, I don't know, but that's one time I'm proud I wasn't no taller than what I am."

Boy, thinking about Buddy and all of those other fiddlers brings back memories of a lot of good old times. But most of them days of fiddling are gone now and there aren't too many in through here that play the old time tunes - they've kind of let them slip away. And that brings back something else that Buddy told me. Now he liked bluegrass just fine, but wanted to play old-time more than he did bluegrass. He said to me, "Lord, son, there always be all kinds of bluegrass fiddlers. Same thing with the banjo: there'll be all kinds of banjo players from now on. But old-time fiddlers, there ain't gonna be many of them at all some of these days. So fiddle is what you want to get after real hard, on them old-time tunes." And I've tried to keep my promise to him about that.

Roger Cooper - 1995

Article MT258

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 6.10.10

A whole lot of musicians would come over to Bob's. Pretty soon somebody'd holler to get Bob's brother Bill. Usually there'd be Shirley Cline and Brooks Mineer over too. They've all got that same lick out through there, Bob and Bill and Brooks, they all got that same rhythm about the way that they play. Bob learned tunes from his dad and from them Rolphs over around Burtonville. They were good strong fiddlers when Bob was growing up, so maybe Bob got some of his style off of them. I used to see Bob's daddy over there when I was a kid. He was about ninety years old but he'd always play a few tunes.

A whole lot of musicians would come over to Bob's. Pretty soon somebody'd holler to get Bob's brother Bill. Usually there'd be Shirley Cline and Brooks Mineer over too. They've all got that same lick out through there, Bob and Bill and Brooks, they all got that same rhythm about the way that they play. Bob learned tunes from his dad and from them Rolphs over around Burtonville. They were good strong fiddlers when Bob was growing up, so maybe Bob got some of his style off of them. I used to see Bob's daddy over there when I was a kid. He was about ninety years old but he'd always play a few tunes.

This habit of Bob's aggravated Buddy Thomas so much that one day he said to me, "We'll just fix Bob of that." So Budd picked me out four or five tunes and planned it all out. He told me, "We'll go down there and first you play these tunes right here. Then hand me the fiddle and I'll be all over him with some of my good stuff. By that time, Bob'll be all wound up and dying to play himself. Then we just get up casual like and leave him there a-hanging." And it all happened just as Buddy said it would and Buddy would laugh about it for days after. It's funny to put that much work into pulling a prank, but that's just the way Budd was.

This habit of Bob's aggravated Buddy Thomas so much that one day he said to me, "We'll just fix Bob of that." So Budd picked me out four or five tunes and planned it all out. He told me, "We'll go down there and first you play these tunes right here. Then hand me the fiddle and I'll be all over him with some of my good stuff. By that time, Bob'll be all wound up and dying to play himself. Then we just get up casual like and leave him there a-hanging." And it all happened just as Buddy said it would and Buddy would laugh about it for days after. It's funny to put that much work into pulling a prank, but that's just the way Budd was.

Ever since Buddy's been my main man in music. I just liked his playing better than anything else I've ever heard and when I try to work up a fiddle tune, I always try to think on how Buddy would have done it. And he was so enjoyable to be around, with all of his jokes a-going and his carrying on all the time. I had the most fun that I ever had in my life when I was around Budd. He'll be dead twenty three years come this fall and I still think about him and his music most nearly every day.

Ever since Buddy's been my main man in music. I just liked his playing better than anything else I've ever heard and when I try to work up a fiddle tune, I always try to think on how Buddy would have done it. And he was so enjoyable to be around, with all of his jokes a-going and his carrying on all the time. I had the most fun that I ever had in my life when I was around Budd. He'll be dead twenty three years come this fall and I still think about him and his music most nearly every day.

So that lunch room was really a great job for Budd, but he got tired of keeping on schedule after awhile and went back to Kentucky. He'd use his mother as an excuse a lot. "Oh, I've got to stay home with Mommy down there, she's getting old." Well, he wasn't too much help to his mother, because she done more work than he ever did. He was just painting a picture, but I think he just got homesick and tired of having to get up everyday.

So that lunch room was really a great job for Budd, but he got tired of keeping on schedule after awhile and went back to Kentucky. He'd use his mother as an excuse a lot. "Oh, I've got to stay home with Mommy down there, she's getting old." Well, he wasn't too much help to his mother, because she done more work than he ever did. He was just painting a picture, but I think he just got homesick and tired of having to get up everyday.

Sometimes in a tune you'll get to a certain part where you'll realize your bow is in an awkward place for you. In order to get the tune to come out, you'll have to bow backwards for a ways until you get to another spot where the bow will turn back the right way for you. A lot of fiddlers will stop and restart the bow when they get to one of those places, to keep the bow movement going forward all the time, but Buddy always said that you had to learn how to keep that bow going when it turns over for you and you find yourself going backwards. Learn to play it that way because there'll be many times you'll have to play coming and going both. I've found what Buddy told me to be true many times, although it's a little awkward until you get used to it. Another master of the bow I knew, George Hawkins, would bow a difficult tune like Martha Campbell forwards and then, just to show you how he could use the bow, he would play it all the way through with the bow a-going backwards. He was so good that, if you didn't pay careful attention, you'd never know which way he was going with it.

Sometimes in a tune you'll get to a certain part where you'll realize your bow is in an awkward place for you. In order to get the tune to come out, you'll have to bow backwards for a ways until you get to another spot where the bow will turn back the right way for you. A lot of fiddlers will stop and restart the bow when they get to one of those places, to keep the bow movement going forward all the time, but Buddy always said that you had to learn how to keep that bow going when it turns over for you and you find yourself going backwards. Learn to play it that way because there'll be many times you'll have to play coming and going both. I've found what Buddy told me to be true many times, although it's a little awkward until you get used to it. Another master of the bow I knew, George Hawkins, would bow a difficult tune like Martha Campbell forwards and then, just to show you how he could use the bow, he would play it all the way through with the bow a-going backwards. He was so good that, if you didn't pay careful attention, you'd never know which way he was going with it.

The trouble was that he'd just soon play you a standard as one of the others and as he got older, it'd be hard to get him on other tunes. And Morris was bad about just playing them short and not playing real long, so it was hard to pick those tunes up. But me and Buddy got some of our best tunes from old Morris. His cousin Abe Keibler is another good fiddler and still going strong at eighty-eight; I've picked up a lot from him too.

The trouble was that he'd just soon play you a standard as one of the others and as he got older, it'd be hard to get him on other tunes. And Morris was bad about just playing them short and not playing real long, so it was hard to pick those tunes up. But me and Buddy got some of our best tunes from old Morris. His cousin Abe Keibler is another good fiddler and still going strong at eighty-eight; I've picked up a lot from him too.

Buddy told me once that he'd been staying at Morris' house for about a week, just burning the fiddle up a-practicing, when Morris looked out the window and said, "Oh, here's Acey Neil and Jimmy Wheeler coming up in an automobile. Let's hide the fiddles under the bed, Buddy." When they came in, Morris asked, "Did you boys bring your fiddles? We ain't got none here and we're just dying to play some fiddle music." Buddy would always laugh and say that they had edged Acey and Jimmy out that day through being real hot from the start.

Buddy told me once that he'd been staying at Morris' house for about a week, just burning the fiddle up a-practicing, when Morris looked out the window and said, "Oh, here's Acey Neil and Jimmy Wheeler coming up in an automobile. Let's hide the fiddles under the bed, Buddy." When they came in, Morris asked, "Did you boys bring your fiddles? We ain't got none here and we're just dying to play some fiddle music." Buddy would always laugh and say that they had edged Acey and Jimmy out that day through being real hot from the start.

"you're the best fiddler here - except for me." Buddy laughed and shook his hand, "I believe you're right." Buddy always thought that was real funny, but Buddy had a lot of respect for George and what he knew about the fiddle.

"you're the best fiddler here - except for me." Buddy laughed and shook his hand, "I believe you're right." Buddy always thought that was real funny, but Buddy had a lot of respect for George and what he knew about the fiddle.