Article MT261

'Awake and join the cheerful choir'

The Reverend Geoffry Hill and his Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries it was the custom to publish song collections under regional titles. Thus, in 1882, we find the Reverend J Bruce & J Stokoe's Northumbrian Minstrelsy. In 1889 the Reverend S Baring-Gould & the Reverend H Fleetwood Sheppard produced their collection Songs and Ballads of the West while, in 1890, the Reverend John Broadwood's revised edition of Sussex Songs appeared. Fourteen years later, in 1904, the Reverend Charles L Marson helped Cecil Sharp produce the first volume of a 5-volume set of Folk Songs from Somerset (1904 - 09). 1 In 1890, another vicar, the Reverend Geoffry Hill

1 In 1890, another vicar, the Reverend Geoffry Hill  2, produced his own regional collection. This was Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols. Compared with the other collections, the Reverend Hill's book was modest in size and scope, and contained but seven folksongs and two carols that had been collected in the village of Britford, just to the south of Salisbury, in Wiltshire.

2, produced his own regional collection. This was Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols. Compared with the other collections, the Reverend Hill's book was modest in size and scope, and contained but seven folksongs and two carols that had been collected in the village of Britford, just to the south of Salisbury, in Wiltshire.  Other collectors, such as Cecil Sharp, Ralph Vaughan Williams or Alfred Williams, made far larger collections and it is tempting to see Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols as little more than a footnote to the history of English folksong collecting activity. But this, I believe, would be wrong because we can learn a considerable amount of information from the book, both about the songs and carols themselves, and about why people such as the Reverend Hill took it upon themselves to 'rescue' such material for posterity. In doing so Geoffry Hill, along with all the other collectors, left us a legacy of immense importance, one that continues to enrich our lives today and one which will, I think, continue to do so for generations to come.

Other collectors, such as Cecil Sharp, Ralph Vaughan Williams or Alfred Williams, made far larger collections and it is tempting to see Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols as little more than a footnote to the history of English folksong collecting activity. But this, I believe, would be wrong because we can learn a considerable amount of information from the book, both about the songs and carols themselves, and about why people such as the Reverend Hill took it upon themselves to 'rescue' such material for posterity. In doing so Geoffry Hill, along with all the other collectors, left us a legacy of immense importance, one that continues to enrich our lives today and one which will, I think, continue to do so for generations to come.

Firstly, though, why was it that so many clerics set about collecting and publishing collections of folksongs? For a start, they were educated men, ones with a university background and they would have been aware that others were also collecting such material. Secondly, their work would have brought them into contact with the sort of people who actually sang, or remembered singing, folksongs. As part of their pastoral work they would have visited the poor and needy and would have been aware that other collectors had obtained songs from such people. Then, being clerics, it may have been the case that they were initially interested in the folk carols that were still being sung in their parishes. And it could well have been the case that the carol singers also knew folksongs, which they would also have sung. Finally, many clerics were trained musicians, ones able to write down folk tunes. Or, if this was not the case, then they had people to hand, such as church organists, who could be brought in to assist in their collecting work. And, unlike present day church people, they probably had sufficient free time in which to collect folksongs.

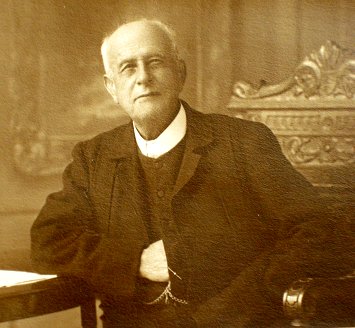

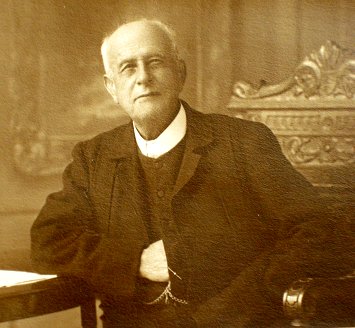

Geoffry Hill was one such person. A lifetime bachelor, he was born in Alderbury, Wiltshire, on October 6th, 1846 and was the son of the Reverend Richard H Hill, then the vicar of Britford. According to the 1851 census Geoffry, described as 'a scholar at home', was then living at Britford Vicarage with his father, then aged 50, two brothers, Cutts William Hill and Alfred Bescoe Hill, his maternal grandmother, Mary Barton, and two servants. Ten years later, in 1861, Geoffry and Alfred had moved to Wales, where they were attending Beaumaris Grammar School, where their elder brother, Ronald Humphry Hill, 36 years of age, was the headmaster. Another brother, Arthur Morris Hill was also a student at the school.

Having left school, Geoffry Hill took up teaching as a profession and, in 1871, was an assistant Classics master at the Grange School, Ewell, in Surrey. However, he did not continue as a teacher and within ten years had trained as a church minister, so that, by 1881, he had become an 'Episcopalian Clergyman Curate' at St John's Episcopalian Church in Edinburgh, Scotland. The Church was built in 1818 and stands in the centre of Edinburgh, in Princes Street. Quite why the Reverend Hill, as we must now call him, should have been at an Episcopalian church is a bit of a mystery, because while the church is 'part of the Anglican Communion', it is not, and never has been, a part of the Church of England. Being an Episcopalian church it is run by its bishops and not by a council of clergy and elders. Over the years the Church has had its disagreements with English authority. It refused, for example, to acknowledge the authority of King William and Queen Mary and, later many Episcopalians supported the Stuart uprisings of 1715 and 1745. Things are somewhat different today but I would like to think that Hill would have agreed with St John's present-day mission statement, which talks of 'engaging with an ever-changing world and living a faith that is timeless yet contemporary, thoughtful and compassionate.'

The Reverend Geoffry Hill is not traced in the 1891 census, but, as this was the year that he moved south from Scotland to become a Church of England vicar in Wiltshire, it may be that he was in transit on the day of the census. The Reverend Hill had become vicar of East and West Harnham, a parish that bordered on his father's old parish of Britford. East and West Harnham were originally two separate parishes with two churches and were united in 1881. St George's in West Harnham is a Norman church, first recorded in a document of 1115 and was, until 1881, a chapelry in the parish of Coombe Bissett. All Saints, East Harnham, was built in 1854 and was, until 1881, a chapelry in the parish of Britford. Geoffry Hill was to spend 34 years as the vicar of East and West Harnham and has been described as 'much beloved by his parishioners'.

The Reverend Geoffry Hill is not traced in the 1891 census, but, as this was the year that he moved south from Scotland to become a Church of England vicar in Wiltshire, it may be that he was in transit on the day of the census. The Reverend Hill had become vicar of East and West Harnham, a parish that bordered on his father's old parish of Britford. East and West Harnham were originally two separate parishes with two churches and were united in 1881. St George's in West Harnham is a Norman church, first recorded in a document of 1115 and was, until 1881, a chapelry in the parish of Coombe Bissett. All Saints, East Harnham, was built in 1854 and was, until 1881, a chapelry in the parish of Britford. Geoffry Hill was to spend 34 years as the vicar of East and West Harnham and has been described as 'much beloved by his parishioners'.

In 1900 the Reverend Geoffry Hill founded the Harnham Cricket Club and was a keen player who captained the team until well into his sixties. One story tells how a rising ball struck him on his cheek, breaking his dentures. The match was on a Saturday and Hill's chief concern was that he would be unable to deliver his sermons on the next day. As it turned out, two other members of his team were dental mechanics and they worked throughout the night to produce a new set of dentures so that Hill was indeed able to preach on the following morning! In 1903 Hill was the founder President of the East and West Harnham Horticultural Society (now the Harnham Flower Show Society), while, in 1906, he founded the Harnham Fife & Bugle Band (membership being conditional on joining the church choir!).  But, of course, from a folk music point of view the Reverend Geoffry Hill is best known for his book Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols. But this was not his only publication. In 1900 he published English Dioceses: a history of their limits from the earliest time to the present day (Elliot Stock, London.). This was followed by The Aspirate, or the use of the letter 'H' in English, Latin, Greek and Gaelic (T Fisher Unwin, London, 1902) and Some Consequences of the Norman Conquest (Elliot Stock, London, 1904).

But, of course, from a folk music point of view the Reverend Geoffry Hill is best known for his book Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols. But this was not his only publication. In 1900 he published English Dioceses: a history of their limits from the earliest time to the present day (Elliot Stock, London.). This was followed by The Aspirate, or the use of the letter 'H' in English, Latin, Greek and Gaelic (T Fisher Unwin, London, 1902) and Some Consequences of the Norman Conquest (Elliot Stock, London, 1904).

Towards the end of his life The Reverend Geoffry Hill was helped in his parochial duties by his widowed sister, Mrs Frances J Grimes. Geoffry Hill died on January 1st, 1925, and was buried in All Saints churchyard, East Harnham. Today his white marble headstone lies against the west wall of the church, having been moved from the grave site when a new road was built across what was once a part of the churchyard. There is an oak screen memorial to the Reverend Geoffry Hill in All Saints, East Harnham, and a memorial stained glass window in St George's Trinity Chapel, West Harnham.

Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols

Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols, the Reverend Geoffry Hill's regional collection, was published in 1890 by W Mate of Bournemouth. It contains the texts and tunes to seven songs and two carols and was priced at just 2 shillings (10p). Why, we might ask, did the Reverend Hill wish to publish this book? Luckily, he gave us the answer in his introduction to the collection.

The main reason for the publication of these Songs and Carols is that they are already almost forgotten, and that if they are not rescued now from the oblivion that is overtaking them, their rescue will be impossible.

Hill continues:

At the present time they are known to the old men of some of our Wiltshire villages, but they are never on their lips; for old age has taken from them both the wish and the power to sing; and their sons and grandsons sing songs of a different stamp.

Interestingly, these two sentiments, that the old songs were no longer being sung and that the younger generation did not wish to sing the songs, were also expressed by Alfred Williams, another collector who, on occasion, also noted song texts in Wiltshire.

Here, now, in the winter evenings, instead of the village gossip of ploughing, threshing, reaping, revelling, and the rest, the talk is chieftly of the town: of football, the cinematograph shows, the theatre, 'Sacco' the fasting freak, and a good deal of other sickly mess and rubbish, not half as manly and interesting as the hearty speech and ready wit of the independent crowd of cheerful rustics that assembled in the big room at the Blue Lion, shouting to the landlord for better beer, and singing snatches of song, some of them well worth remembering, such as this of the old carter's, rarely tender, and suggestive of a beautiful story:

We never speak as we pass by,

Althoug a tear bedims her eye;

I know she thinks of our past life,

When we were loving man and wife…

Or the old poaching song of Thorneymoor Fields:

Now Thorneymoor Fields are in Nottinghamshire,

Right whack ti fa lary, right whack ti fa laddie de;

Now Thorneymoor Fields are in Nottinghamshire,

Right whack ti fa laddie ee day.

The very first night we had bad luck,

For one of our very best dogs got shot,

For one of our very best dogs got shot,

Right whack ti fa laddie ee day.

A good many of these old songs and chanties survived about the villages till late years, but they are fast dying out now, and are replaced by the idiotic airs of the music-hall, or the sound of music is heard no more. 3

3

The Reverend Geoffry Hill described these latter songs thus:

They are partly the songs of the London music halls, which probably have their merits as well as their demerits; and they are partly songs which seem to have no redeeming quality at all. They have not the 'swing' of the music hall songs, and their wording is either weakly sentimental, or distinctly low in tone.

In common with other collectors, Hill tried to trace his songs to a specific location, in this case Wiltshire.

How far these songs and Carols possess a Wiltshire origin, I find it impossible to say. One of the songs I know to come from Hampshire; one of the carols is also claimed by a Dorsetshire village.

Today we know that English folksongs spread throughout the country by way of printed broadsides and that songs described as 'Wiltshire' by the Reverend Hill, or 'Somerset' by Cecil Sharp, are usually versions of songs that have often turned up all over the place. Hill clearly had some knowledge of folksongs outside Wiltshire, as this comment shows:

…there is an Edinburgh song, with nothing either specially Highland or Lowland about it, each verse of which ends with 'To Dalkeith wi' a Soldier'.

Presumably Hill had heard this song being sung in Edinburgh during his stay there as an Episcopalian curate.

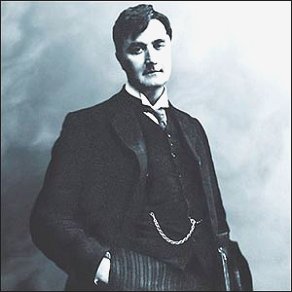

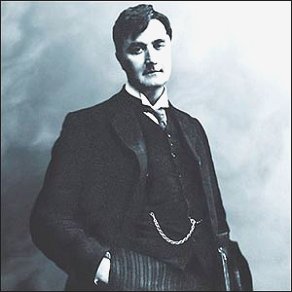

It seems likely that the Reverend Hill was unable to write the music down for the songs that he heard. Accordingly he enlisted the help of a friend, Walter Barnett, an 'Organist and Professor of Music'. 4 Barnett was born in Salisbury in 1857. In the Musical Times of January 1st, 1877, there is mention of Barnett being appointed organist to St Andrew's Church, South Newton, Salisbury. We know that on July 5th, 1890, Barnett married a widow, Eliza Ann Kendle, nee Stagg, the wedding taking place in Salisbury. And we also know that Walter Barnett was both a Fellow of the Royal Society of Antiquaries and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

4 Barnett was born in Salisbury in 1857. In the Musical Times of January 1st, 1877, there is mention of Barnett being appointed organist to St Andrew's Church, South Newton, Salisbury. We know that on July 5th, 1890, Barnett married a widow, Eliza Ann Kendle, nee Stagg, the wedding taking place in Salisbury. And we also know that Walter Barnett was both a Fellow of the Royal Society of Antiquaries and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

In Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols Walter Barnett explains how he noted the tunes that are found in the book and in some of the problems that he encountered.

It is not suggested that the whole of these melodies are now published for the first time; some of them, at least, have appeared in previous collections, differently arranged and set to other words. Nor do I claim to have discovered the original form of the tunes. They were taken down from the mouths of old men who, in some instances, had not sung them for many years; and considerable allowance had to be made for lapses of memory which frequently led to the confusion of one melody with another.

Further difficulty in the way of making sure of the correct form of a tune lay in the fact that when these songs were sung, it was usual for each singer to have his own particular song which was seldom sung by anyone else. I have had, therefore to rely implicitly upon a single version of each melody, because only one man could be found who knew it … I have in no case 'patched up' a melody. As with the words, so with the tunes, these songs are given here exactly as they were sung; while the accompaniments, for which I alone am responsible, are purposely simple and unobtrusive. This will, I trust, give the songs a value which otherwise they would not possess.

Barnett also provided a few notes to the songs themselves.

Of the songs individually I need say but little. Few will fail to be struck with the fine melodies of 'Long time I've travelled in the North Countrie' and 'Botany Bay'; while it will be generally admitted that the really graceful air, 'Oh, where Best Gwying?' is worthy of better words. It has already been remarked by my friend, Mr Hill, that the tune of 'Ye Sons of Albion' is almost, if not quite, identical with that of a well-known song, 'The farmer's Boy'. The stirring character, however, would seem to indicate that it was originally composed to martial words, such as those given in this collection. The two carols … are probably of comparatively modern date.

According to Geoffry Hill:

When I lighted upon them (i.e. the songs and carols), they were all being sung in one small village near Salisbury … (they) were sung in the Vicarage kitchen by the parish bellringers at their New Year's supper, and the carols were sung on the Vicarage lawn on the night of Christmas.

The village in question was Britford and it is tempting to think that Hill collected the songs just prior to their publication in 1890. However, in his notes to the song Ye Sons of Albion Hill says that, 'The song comes from one of the Winterbournes in the Bourne Valley. Its date is fixed by its reference to the expected invasion of England by Napoleon in 1804. The man who sang it thirty years ago was himself one of the volunteers of that year.' So, is Hill saying that he heard, and collected, the song sometime around 1860? If Hill had collected the song just prior to 1890 then it is surely unlikely that this singer, who must by then have been extremely old, would have physically been able to serve as a bellringer, although, of course, he could have been there as a guest. And, of course, Walter Barnett, who noted the tunes, would only have been about 7 years old in 1860!

Sadly we are told very little about the singers. We are not given any of their names and are only told that some of the singers learnt the songs outside the village sometime before they moved to Britford. Having said that, I might suggest that there is a slight possibility that we may, in fact, know the name of one of the singers, namely the person who sang The Taking of Quebec. In Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols the Reverend Hill says that, 'This song comes from Durrington, near Stonehenge.' Presumably, this means that the singer, who was living in Britford when he sang to Hill, either learnt the song in Durrington, or else originally came from Durrington.  On 1st September, 1904, Ralph Vaughan Williams collected a version of the song Erin's Lovely Home (Roud 1427) from a singer called Charles Smith, who was then living in the St Nicholas Hospital, Salisbury, and who had been introduced to Vaughan Williams by Hill. According to Vaughan Williams, 'Mr Smith was originally from 'Durrington, near Amesbury', though he had later 'settled in Britford'. So, was Charles Smith also the singer of The Taking of Quebec? It is now too late to be certain, but it remains a distinct possibility.

On 1st September, 1904, Ralph Vaughan Williams collected a version of the song Erin's Lovely Home (Roud 1427) from a singer called Charles Smith, who was then living in the St Nicholas Hospital, Salisbury, and who had been introduced to Vaughan Williams by Hill. According to Vaughan Williams, 'Mr Smith was originally from 'Durrington, near Amesbury', though he had later 'settled in Britford'. So, was Charles Smith also the singer of The Taking of Quebec? It is now too late to be certain, but it remains a distinct possibility.

Vaughan Williams also collected five other songs in Salisbury that day. As well as visiting the St Nicholas Hospital he also visited the Salisbury Union, a workhouse. In 1904, Salisbury Union was located in the Reverend Hill's parish of East Harnham, so did Hill accompany Vaughan Williams to the Union to help him collect songs? The five songs were The Isle of France (Roud 1575), sung by William Blake; The Bonny Bunch of Roses (Roud 664), sung by 75 year old Maria Pearce; Come All You Young Ladies and Gentlemen (Roud 157), sung by Charles Shears, who was originally from Winterslow in Wiltshire; Ground for the Floor (Roud 1269), sung by Elias Coombes, a former shoemaker; and a short version of Lord Bateman (Roud 4), sung by John Mitchell, who was then aged 'about 60 years'. Vaughan Williams collected a further two songs in Salisbury, in September, 1904, although we do not have the exact collecting date. These were versions of The Buffalo (Roud 1026) and Edwina of Waterloo (Roud 1566), both sung by a Mr Leary who was then living in the Salisbury Almshouses in Castle Street, Salisbury.

The Songs and Carols

The songs included in Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols are Long Time I've Travelled in the North Countrie, The Taking of Quebec, The Labouring Man, Ye sons of Albion, Botany Bay, There was a Rich Merchant, Oh Where Be'est Gwying? and the Britford First Carol (Rejoice, the promised saviour's come) together with the Britford Second Carol (Awake and join the cheerful choir). I have included the texts of each song below, together with the Reverend Hill's individual song notes, indicated by (RGH) and my own additional notes, indicated by (MY) which, I hope, will be of interest to readers.

Long Time I've Travelled in the North Countrie

Long time I've travelled in the North countrie,

A seeking for good companie,

Good companie I always could find,

But none that suited to my mind.

To sing wack fal the ral,

Ral the riddle dee,

I've in my pocket but one penny.

O there I saw three noble knights,

As they were a playing of dice,

As they were at play and I looked on,

They took me to be some noble man.

To sing wack fal the ral,

Ral the riddle dee,

I've in my pocket but one penny.

They asked me if I would play,

I asked they what bets they would lay,

The one says a guinea, the other five pound,

The bet it was made, but the money down.

To sing wack fal the ral,

Ral the riddle dee,

I've in my pocket but one penny.

I took up the dice and threw them in,

'Twas my good fortune to win,

If they had o' won and I had o' lost,

I must have shook out my empty purse.

And sung wack fal the ral,

Ral the riddle dee,

I've in my pocket but one penny.

Was there ever a mortal man so glad,

As I was with the money I had?

I'm a hearty good fellow and that you shall find,

I'll make you all drunk boys a drinking of wine.

To sing wack fal the ral,

Ral the riddle dee,

I've in my pocket but one penny.

I tarried all night and part the next day,

Till I thought it high time to be jogging away,

I asked the young landlady what was to pay,

Oh, only one kiss my love, go your way

And sing wack fal the ral,

Ral the riddle dee,

I've in my pocket but one penny.

(RGH) The singer was a Hampshire man, and he brought his song with him into the village of Britford.

(MY) Roud 393. This song seems to have begun life as a late 17th century blackletter broadside, titled The Adventures of a Penny or The Hearty Good Fellow. A L Lloyd has suggested that its popularity in southern and western England was based on a broadside issued by John Pitts in London, whereas a broadside issued by Kendrew of York kept the song alive in the midlands and the north of the country. Collected versions include those sung by the Gypsy singer Levi Smith (Topic TSCD 661) and the Black-Country singer George Dunn (Topic TSCD 663 and Musical Traditions MTCD317-8).

The Taking of Quebec

A Monday morning when we set sail,

The wind it blew a pleasant gale.

To meet the French was our desire.

Through smoke and fire,

Old England shall win the day.

The French they stood on mountains high,

While we poor soldiers in the valley lie.

'Oh never mind that', old Wolfe did say.

Fight on so boldly,

Old England shall win the day.

The very first broadside that we gave them,

We killed five hundred and fifty men.

'That's very well done,' General Wolfe did say.

Fight on so boldly, fight on so boldly,

Old England shall win the day.

The first broadside that the French did give us,

They wound our General in his right breast.

The life blood from the wound did flow.

Which caused our soldiers, which caused our soldiers,

Great sorrow and woe.

You bold commanders that round me stand,

Pray take me by my bleeding hand.

And throw me in the water deep.

There let me lie, there let me lie,

And take a long, silent sleep.

Here's a hundred pound in bright red gold,

Take and part it, my blood runs cold.

Take it and part it old Wolfe did say.

Still fight on boldly, still fight on boldly,

Old England shall win the day.

(RGH) This song comes from Durrington, near Stonehenge. We may be morally certain that it was composed by one of the 62nd, for the Wiltshire Regiment was with Wolfe at the taking of Quebec. The statement in the second verse about the relative position of the French and English armies, and the mention of the day of the week on which Wolfe started from England, or on which the battle was fought, point to the author's having been with Wolfe on the heights of Abraham.

(MY) Roud 624. The Reverend Hill makes an interesting point about the historical accuracy of the events mentioned in this song. However, it should be born in mind that these details would also have been reported widely in the press of the day, and broadside writers would have been well aware of the events from such sources. At least five southern English broadside publishers issued the song under the title Bold General Wolfe. Three printers were from London (Catnach, Ryle and Such), while the other two were from Bristol (Marshall) and Southborough (Pierce); and collected sets have all been from the southern and south-eastern counties of England. (I should add that Percy Grainger did find a version of the song in Lincolnshire, but this is the only known version from a singer living north of Suffolk.) Recorded versions are available from Bob Hart (Musical Traditions MTCD 301-2) and Cyril Poacher (Musical Traditions MTCD 303), both from Suffolk, and the Copper Family of Sussex (Topic TSCD 534). There are also BBC recordings from Pop Maynard and George Bloomfield.

The Labouring Man

You Englishmen of each degree,

A moment listen unto me.

To please you all I do intend,

With these few lines I'm going to pen.

From day to day you all may see,

The poor are frowned on by degree.

By them, you know, who never can,

Do without the labouring man.

Chorus

Now let England do the best she can,

She can't do without the labouring man.

Old England always leads the van,

But never without the labouring man.

In former days you all do know,

A poor man cheerful used to go.

Neat and clean upon my life,

With his children and his wife.

And for his labour it was said,

A fair day's wages he was paid.

Chorus

When Bonaparte and Nelson too,

And Wellington at Waterloo.

Were fighting both by land and sea,

The poor man gained the victory.

Their hearts were cast in honour's mould,

The soldiers and sailors bold.

Chorus

Now, if wars do rise again,

And England be in want of men.

They'll have to search the country round,

To find the lads that plough the ground.

Who harrow the ground and till the wheat,

And every danger boldly meet.

Chorus

(RGH) This song comes from the same village as the former (The Taking of Quebec) and was sung by the same man.

It may surprise many to be told that there is no class of Englishmen so intensely patriotic as the farm labourers; and we can see the reason for their patriotism when we remember that their fathers fought for England, not by bearing an increased load of taxation, but with their own hands. The richer classes might well be patriotic, for their sons won by war promotion and reputation. But the labouring class won nothing; they only knew that they had met the French in fair fight and had beaten them. This, with their old English love of fighting, was enough; they loved England not for what England had done for them, but for what they had borne for England; if ever there was an unselfish love it was theirs. But if his love was unselfish, the English labourer was well aware at what cost he had proved it. Napier, in his Peninsular War, tells us that it was not English generalship that beat the French, but the doggedness of the English infantry; and if this fact was apparent to Napier, it was equally apparent to the men who had shewn the doggedness. How well then can we understand the bitterness with which Wellington's troops on their return from the Peninsular viewed the state of things then existing in England! They saw that Protection and the French War had so raised the price of bread, that the men and women of their own class were almost starving; and they soon found that they themselves had to bear the pinch of poverty. Little wonder was it that men who knew that they had given England her proud position among the nations of Europe at the risk of their own lives, expressed themselves bitterly and extravagantly at the treatment which they received at the hands of their countrymen.

(MY) Roud 1156. Clearly a song that post-dates the Battle of Waterloo. It was published on mid-19th century broadsides by at least three London printers (Disley, Fortey & Such) and there are collected sets from Lucy Broadwood (Surrey), Henry Hammond (Dorset) and George Gardiner (Hampshire).

Ye sons of Albion

Ye sons of Albion, take up your arms,

To meet those haughty bands;

They threaten us with war's alarm,

T'invade our native land.

Chorus

Nor the rebel French, the Sans culottes,

Nor dukes of tyranny bold,

Shall conquer the English, the Irish, the Scotch,

Nor land upon our coasts,

Nor land upon our coasts.

You commanders of the universe,

Or else you'd wish to be,

Now we will shew you quite reverse,

And set old England free.

Chorus

Here's hopless Holland wears the yoke,

And so does faithless Spain,

But we will shew them hearts of oak,

And drive them from the main.

Chorus

(RGH) This song comes from one of the Winterbournes in the Bourne Valley: Its date is fixed by its reference to the expected invasion of England by Napoleon in 1804. The man who sang it thirty years ago was himself one of the volunteers of that year. No song could breathe more intense defiance of a national foe; from it we may grasp the spirit of that volunteer army which, but for Nelson, might have met Napoleon on English soil.

(MY) Roud 1157. This is quite a rare song. It is only known to have been collected on one other occasion, by William Alexander Barrett, who included a version of the song in his book English Folk-Songs (1891), and there is only one known broadside, by James Lindsay of 9, King Street, (off Trongate), Glasgow, who was known to be printing between the years 1851 and 1910.

Botany Bay

Come all young men of learning,

A warning take by me.

I'd have you quit night walking,

Or else you'll rue the day.

I'd have you quit night walking,

Or else you'll rue the day.

Oh, when you are transported,

And going to Botany Bay.

I was brought up in London Town,

A place I know right well.

Brought up by honest parents,

With whom I loved to dwell.

Brought up by honest parents,

And reared so tenderly.

Till I became a roving blade,

Which proved my destiny.

My character was taken,

And I was sent to jail.

My friends they tried to clear me,

But nothing could prevail.

My friends they tried to clear me,

But the judge to me did say.

'The jury find thee guilty,

Thee must go to Botany Bay'.

To see my aged father,

As he stood at the bar,

Likewise my tender mother,

Her old grey locks she tore.

My broken hearted mother,

Who unto me did say.

'Oh son, Oh son, what have thee done,

For to go to Botany Bay'.

There is a girl in London Town,

A girl I know right well.

And if I ever get my freedom,

Along with her I'll dwell.

If I ever get my freedom,

I'll marry her the day.

I'll shun all evil company,

Then adieu to Botany Bay.

(RGH) Sung by a Britford man, whose forefathers had been in the parish for generations. It was sung with great feeling, and naturally; for Botany Bay was to the English labourer who stole a sheep, a stern reality.

(MY) Roud 261. This is an extremely well-known and popular folksong. Several English collectors noted versions of the piece and it has also turned up in many parts of North America and, not surprisingly, Australia itself. Botany Bay was, of course, 'discovered' by Captain James Cook on 29th April, 1770, and was the first Australian landing point for Cook and the men of HMS Endeavour. Shortly afterwards the site was developed into a British penal colony. Hill's text is similar to those published on 19th century broadsides by Forth of Hull, Harkness of Preston and Such of London. There is a recording of Jumbo Brightwell singing his version of the song on Veteran VT154CD. American versions, usually titled The Boston Burglar, are available from Nova Baker and Elsie Vanover (Musical Traditions MTCD506) and Kevin Mitchell (Musical Traditions MTCD315).

There was a Rich Merchant

There was a rich merchant in London did dwell,

He had but one daughter, a beautiful girl.

She was neat, tall and handsome, she was beautiful and fair,

And was sent to her uncle for the space of one year.

She had not been there, past a month and a day,

When her true love sent a letter, to fetch her away.

And she had not the patience, to wait for her dear,

But straight on the road this young damsel did steer.

There was one road upward and the other going down,

This young damsel being weary, she set herself down.

And she fetched a long sigh and her tender heart did break,

And she died on the road for her true lover's sake.

Now the young man being weary he called at an inn,

He called for a bottle to drink with some friends.

What new brother sailor, what news from abroad,

Have you heard of the damsel that died on the road?

Then the young man he resolved her corpse for to see,

He viewed all around and he found it was she.

Then he says, 'It's my true love and the only one I have,

And I'm quite resolved that we lie in one grave.'

(RGH) A Britford song. It (sic) style seems more antique than that of any other song in the collection. It has points of resemblance to the 'Bailiff's Daughter of Islington'.

(MY) Roud 1651. Another rarity in the oral tradition, though it was quite widely printed on 18th century broadsides and garlands as The Two Loyal Lovers of Exeter in 26 stanzas, by Turner of Coventry, Johnson of Falkirk, Aldermary Churchyard, Belfast etc. It has been collected a few times under various titles; such as There was a Rich Merchant, The Rich Gentleman's Daughter, The Shopkeeper or In Rochester City. Lucy Broadwood collected a set in Oxfordshire, Alfred Williams noted a single text in Gloucestershire and George Gardiner found no fewer than four versions of the song being sung in Hampshire a few years after the Reverend Hill published his version. It should not be confused with the similarly titled The Rochester Lass (Roud 1158). It is not, of course, 'a Britford song', but rather the work of the broadside press.

Oh Where Be'est Gwying?

Oh where be'est gwying, my pretty maid.

Oh where be'est gwying, so early.

I be gwying kind sir, to yonder green drove,

Where my father be mowing of barley.

I be gwying kind sir, to yonder green drove,

Where my father be mowing of barley.

Shall I go with you, my pretty maid?

Shall I go with you my honey?

Oh no, kind sir, she answered and said,

For I'm not a gwying to ruin.

Oh no, kind sir, she answered and said,

For I'm not a gwying to ruin.

The lawyer he got off his horse,

Oh for to take some pleasure.

Oh will you give me one sweet kiss,

For a handful of gold and silver?

Oh will you give me one sweet kiss,

For a handful of gold and silver?

Oh keep your gold and silver too,

For I'm not a gwying to ruin.

For it's all such rogues and rascals as you,

As brings poor girls to ruin.

For it's all such rogues and rascals as you,

As brings poor girls to ruin.

(RGH) A Britford song. Whether there is here the whole song it is impossible to say. When a labourer was asked to give the words he declared that he had entirely forgotten them. By dint of perseverance one verse was obtained and then four.

(MY) Roud 922. Often called The Lawyer or Mowing the Barley versions of this song have turned up all over the place. The composer George Butterworth noted versions in Herefordshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire and Sussex, while Cecil Sharp found it being sung in Warwickshire and Somerset. Henry Hammond found the song in Dorset, George Gardiner found several sets in Hampshire and Surrey and Ralph Vaughan Williams collected a single set in Sussex. Current recordings include those by Walter Pardon of Norfolk (Topic TSCD514) and George Dunn from the Midlands (Musical Traditions MTCD317-8).

Britford First Carol

Rejoice, the promised saviour's come,

And shall the blind behold.

The deaf shall hear and by the dumb,

His wondrous works be told.

His wondrous works be told.

Light from the sacred shore shall spread,

O'er all the world shall beam.

In pastures fair shall all be led,

And drink of comfort's stream.

And drink of comfort's stream.

The weary nations shall have rest,

The rage of was shall cease.

The earth with innocence be blest,

And plenty dwell in peace.

And plenty dwell in peace.

(MY) Roud 1159. Please see the note following the Britford Second Carol.

Britford Second Carol

Awake and join the cheerful choir,

Upon this joyful morn,

Upon this joyful morn.

And glad Hosannas loudly sing,

And glad Hosannas loudly sing.

For joy, a Saviour's born,

For joy an Saviour's born.

Let all the choirs in earth below,

Their voices loudly raise,

Their voices loudly raise.

And sweetly join the cheerful band,

And sweetly join the cheerful band.

Of angels in the skies,

Of angels in the skies.

The shining host in bright array,

Descend from Heaven to earth,

Descend from Heaven to earth.

And all the gentle heart and voice,

And all the gentle heart and voice.

Proclaim a Saviour's birth,

Proclaim a Saviour's birth.

(RGH) One of the carols is also claimed by a Dorsetshire village.

The two carols…are probably of comparatively modern date. - Walter Barnett

(MY) Roud 1160. Although the Reverend Hill mentions that one carol is known in Dorsetshire he does not say which one and the Roud entries only give the Britford references. However, there is a version of Awake and Join the Cheerful Choir in the George Hanford Book, dated1830, which is housed in the Dorset County Museum. The carol was also known to the writer Thomas Hardy, also from Dorset, and a recording of this version can be heard on the CD Under the Greenwood Tree (Saydisc CD-SDL360). It may be that Reverend Hill was aware of the Hardy version. Accordingly Awake and Join the Cheerful Choir could be the carol that Hill says was 'claimed by a Dorsetshire village'.

After writing this piece I sent a copy to Rod Stradling for his comments and was intrigued by one of his remarks: It's also interesting that few of the 'first generation' of collectors collected many carols. I know there were a few books of them, but only a fraction of the 'folk songs' collected at that time. And, of course, Rod is quite right. So, why were so few carols collected?

Perhaps it would be best to begin by having a brief look at those carols that were collected. Collectors were certainly on the lookout for anything that had appeared in Professor Child's major work, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads; such as St Stephen and Herod (Child 22), The Cherry-Tree Carol (Child 54), The Carnal and the Crane (Child 55) or Dives and Lazarus (Child 56). Then there were other carols that seemed to hold traces of Medieval beliefs, such as The Bitter Withy (Roud 452), Down in Yon Forest (Roud 1523) or The Leaves of Life (Roud 127). Take Down in Yon Forest as an example. It was the sort of thing that intrigued the early collectors, who spent much of their spare time trying to work out just what it meant exactly.

Down in Yon Forest

Down in yon forest there stands a hall

The bells of paradise I heard them ring

Is covered all over with purple and pall

And I love my Lord Jesus above anything

And in that hall there stands a bed

It's covered all over with scarlet so red

And in that bed there lies a knight

Whose wounds they do bleed by day and by night

And by that bedside there kneels a maid

And there she do weep by night and by day

And by that bedside there flows a flood

The one half runs water, the other half blood

And at that bedfoot there lies a hound

A-licking the blood as it daily runs down

And at that bed's head there grows a thorn

Which ever blows blossom since he was born

Was this, perhaps, a remnant of a grail legend, one in which Joseph of Arimathea's Glastonbury thorn ('Which ever blows blossom since he was born') has become attached? What was important, to the collectors that is, is that carols such as this one, and other such as The Bitter Withy or The Cherry-Tree Carol, were collected from individual singers and that individual versions varied from one another. If we look at this from, say, Cecil Sharp's viewpoint, then such carols fit into the collector's idea of just what constituted a folksong. Cecil Sharp's well-known idea of continuity, variation and selection was important not only to Sharp but to most of the other collectors at that time. Carols, that is carols which were sung in church by choirs, just did not fit into Sharp's scheme of things. Such pieces were fixed in form, often being printed in books. Here there was little or no variation from performance to performance. And there was no selection by the singers themselves, this being the job of the choirmaster or church organist. In short, they were not folk and, as such, of little interest to the collectors. This is perhaps why Cecil Sharp once said that he was, 'weak in hymnology'.

Do you remember what the organist Walter Barnett had to say of the Britford carols? They were, he said, 'probably of comparatively modern date'. They were not like Down in Yon Forest or the other folk carols, which, as we have seen, stem from way back in time. Nor were they like the seven folksongs that appear in the book Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols, because, unlike the folksongs, these carols were modern. Nevertheless, we should be grateful to Reverend Geoffry Hill and to Walter Barnett because, despite their feelings, they still managed to preserve these two carols for us, and, who knows, perhaps one day they will again be 'sung on the Vicarage lawn on the night of Christmas'.

Acknowledgements

Firstly I must express my gratitude to William Alexander of Salisbury, whose advice and help was invaluable in the preparation of this article. Also my thanks to Frank Weston, for help with genealogical queries, to Malcolm Taylor, Librarian of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, who has helped in so many ways over the years, and to Julian Jackson, who kindly sent me copies of the Geoffry Hill photographs. And, of course, not forgetting Rod Stradling whose knowledge of traditional carols was of great help.

Mike Yates - 14.1.11

Footnotes

1. Thanks to a new book, David Sutcliffe's The Keys of Heaven. The Life of Revd Charles Marson. Socialist Priest and Folk Song Collector (Cockasnook Books, Nottingham, 2010), we now know that Marson played a far greater part in helping Cecil Sharp collect folksongs than had previously been realized. Marson, it seem, was aware that John England, Sharp's 'first singer', knew songs several months before Sharp noted the song The Seeds of Love from him and it was Marson who introduced Sharp to the singers Louie Hooper and her half-sister Lucy White. According to David Sutcliffe, 'Not many vicars of that time would have embraced these two characters.'

2. Hill's Christian name is spelt 'Geoffry' and not 'Geoffrey'.

3. Alfred Williams Villages of the White Horse. 1913, reprinted 2007 by Nonsuch Publishing, Stroud. p.89. For more on Alfred Williams, see my article The Folk Hero: A different drummer, Alfred Williams and the Edwardian Folk Song Revival at http://www.alfredwilliams.org.uk/folkhero.html

4. As described in the 1901 census.

Article MT261

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 11.3.14

Other collectors, such as Cecil Sharp, Ralph Vaughan Williams or Alfred Williams, made far larger collections and it is tempting to see Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols as little more than a footnote to the history of English folksong collecting activity. But this, I believe, would be wrong because we can learn a considerable amount of information from the book, both about the songs and carols themselves, and about why people such as the Reverend Hill took it upon themselves to 'rescue' such material for posterity. In doing so Geoffry Hill, along with all the other collectors, left us a legacy of immense importance, one that continues to enrich our lives today and one which will, I think, continue to do so for generations to come.

Other collectors, such as Cecil Sharp, Ralph Vaughan Williams or Alfred Williams, made far larger collections and it is tempting to see Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols as little more than a footnote to the history of English folksong collecting activity. But this, I believe, would be wrong because we can learn a considerable amount of information from the book, both about the songs and carols themselves, and about why people such as the Reverend Hill took it upon themselves to 'rescue' such material for posterity. In doing so Geoffry Hill, along with all the other collectors, left us a legacy of immense importance, one that continues to enrich our lives today and one which will, I think, continue to do so for generations to come.

The Reverend Geoffry Hill is not traced in the 1891 census, but, as this was the year that he moved south from Scotland to become a Church of England vicar in Wiltshire, it may be that he was in transit on the day of the census. The Reverend Hill had become vicar of East and West Harnham, a parish that bordered on his father's old parish of Britford. East and West Harnham were originally two separate parishes with two churches and were united in 1881. St George's in West Harnham is a Norman church, first recorded in a document of 1115 and was, until 1881, a chapelry in the parish of Coombe Bissett. All Saints, East Harnham, was built in 1854 and was, until 1881, a chapelry in the parish of Britford. Geoffry Hill was to spend 34 years as the vicar of East and West Harnham and has been described as 'much beloved by his parishioners'.

The Reverend Geoffry Hill is not traced in the 1891 census, but, as this was the year that he moved south from Scotland to become a Church of England vicar in Wiltshire, it may be that he was in transit on the day of the census. The Reverend Hill had become vicar of East and West Harnham, a parish that bordered on his father's old parish of Britford. East and West Harnham were originally two separate parishes with two churches and were united in 1881. St George's in West Harnham is a Norman church, first recorded in a document of 1115 and was, until 1881, a chapelry in the parish of Coombe Bissett. All Saints, East Harnham, was built in 1854 and was, until 1881, a chapelry in the parish of Britford. Geoffry Hill was to spend 34 years as the vicar of East and West Harnham and has been described as 'much beloved by his parishioners'.

But, of course, from a folk music point of view the Reverend Geoffry Hill is best known for his book Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols. But this was not his only publication. In 1900 he published English Dioceses: a history of their limits from the earliest time to the present day (Elliot Stock, London.). This was followed by The Aspirate, or the use of the letter 'H' in English, Latin, Greek and Gaelic (T Fisher Unwin, London, 1902) and Some Consequences of the Norman Conquest (Elliot Stock, London, 1904).

But, of course, from a folk music point of view the Reverend Geoffry Hill is best known for his book Wiltshire Folk Songs and Carols. But this was not his only publication. In 1900 he published English Dioceses: a history of their limits from the earliest time to the present day (Elliot Stock, London.). This was followed by The Aspirate, or the use of the letter 'H' in English, Latin, Greek and Gaelic (T Fisher Unwin, London, 1902) and Some Consequences of the Norman Conquest (Elliot Stock, London, 1904).

On 1st September, 1904, Ralph Vaughan Williams collected a version of the song Erin's Lovely Home (Roud 1427) from a singer called Charles Smith, who was then living in the St Nicholas Hospital, Salisbury, and who had been introduced to Vaughan Williams by Hill. According to Vaughan Williams, 'Mr Smith was originally from 'Durrington, near Amesbury', though he had later 'settled in Britford'. So, was Charles Smith also the singer of The Taking of Quebec? It is now too late to be certain, but it remains a distinct possibility.

On 1st September, 1904, Ralph Vaughan Williams collected a version of the song Erin's Lovely Home (Roud 1427) from a singer called Charles Smith, who was then living in the St Nicholas Hospital, Salisbury, and who had been introduced to Vaughan Williams by Hill. According to Vaughan Williams, 'Mr Smith was originally from 'Durrington, near Amesbury', though he had later 'settled in Britford'. So, was Charles Smith also the singer of The Taking of Quebec? It is now too late to be certain, but it remains a distinct possibility.