Note: Place cursor on graphics for citation and further information.

Sound clips are shown by the name of the song being in underlined bold italic red text. Click the name and your installed MP3 player will start.

Article MT275

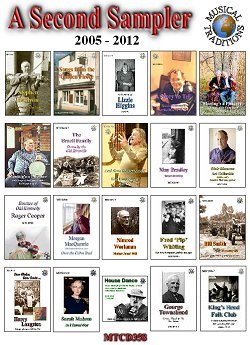

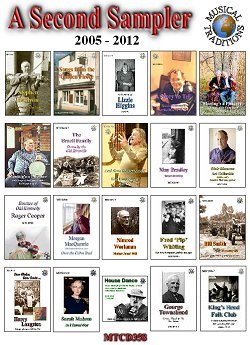

A Second Catalogue Sampler

20 publications, 31 CDs - 2005 to 2012

Track List:

1 -

2 -

3 -

4 -

5 -

6 -

7 -

8 -

9 -

10 -

11 -

12 -

13 -

14 -

15 -

16 -

17 -

18 -

19 -

20 -

21 -

22 -

23 -

24 -

25 -

26 -

27 -

28 -

29 -

30 -

|

Napoleon's March

The Death of Parker

The Flowers of Bermuda

The Beggar Man

Johnny Sangster

The Drowned Lover

The Barndance

The Inconstant Lover

My Little White Hat

Somebody Gonna Miss Me

The Yellow Rose of Texas

Son Come Tell it Unto Me

The Poor Smuggler's Boy

Two Stepdances

The Bishop of Worcester

On Christmas Day

Paddy on the Turnpike

Pretty Little Indian

Warlocks Set

Oh Death!

Will the Waggoner

Ram She Add-a-Dee

Posey Joe

The County Galway Girl

The Month of January

Miss Jenny

Old Dan Tucker

Shooting Goshens Cockups

Has Anybody Seen My Tiddler?

The Burial of Sir John Moore

|

Stephen Baldwin

Audrey Smith

Bob Bray

Lizzie Higgins

Lizzie Higgins

Jumbo Brightwell

Fred List

Buell Kazee

Dixon Sisters

Perry Riley

J P Fraley

Weenie Brazil

Angela Brazil

Lemmie Brazil

Ken Langsbury

May Bradley

Art Galbraith

Roger Cooper

Morgan MacQuarrey

Nimrod Workman

Fred 'Pip' Whiting

Bill Smith

Harry Langston

Sarah Makem

Sarah Makem

Sarah Makem

Dooley Chapman

Jack Smith

George Belton

George Townshend

Duration:

|

1:27

3:18

2:43

3:31

3:41

3:40

1:05

3:49

2:43

2:42

1:31

3:15

2:20

1:14

5:42

2:20

1:43

1:42

3:48

1:49

1:25

1:45

4:05

2:12

4:47

1:51

1:33

3:16

1:46

2:55

79:34

|

|

|

Since its earliest days as a paper magazine, Musical Traditions magazine has been producing cassettes of important music which was not commercially available in the UK. Later, after the move to the Internet, we started production of a new series in CD-R format, and the first of these - a double CD of Suffolk singer Bob Hart - was published in June 1998.

So it's now about fourteen years since MT started issuing CDs. In that time a startling 85 discs (2 triples, 19 doubles, 26 singles, plus 15 CD-ROMS and several peripherals) have emerged from my little wind-powered forge here in Stroud. The change to a new packaging format in 2002 (DVD case with integral booklet) resulted in the eventual conversion of all our CDs to that format.

That first sampler (2005) featured 26 tracks from the 33 records then published in the '300' series; this second one covers the period from 2005 to the present - summer 2012 - and a further 20 publications containing 31 CDs.

My hope is that this full and inexpensive CD may find a wider audience than any of the individual publications have, and may open a few eyes to the riches to be found within MT's catalogue, of which it has been said:

... some of the best collections available of traditional music - Steve Winnick, writing in Dirty Linen

... this small but very valuable catalogue - Vic Smith in fRoots

And of our CD booklets: ...

a very significant contribution to folk-song scholarship - Dave Atkinson in Folk Music Journal

The present selection has to be seen as nothing more than my current favourite tracks, or things you will never have heard before; one from each CD, in the order that they were released - and I've made no attempt to be representative of any particular singer's repertoire or style. Even then it has been a very difficult selection and a number of lovely things from the several 'various performers' CDs have had to be omitted for lack of space.

All of the following text is drawn from the booklets accompanying the CDs, suitably edited for this publication.

Rod Stradling - July 2012

The Singers and Musicians: their songs and tunes

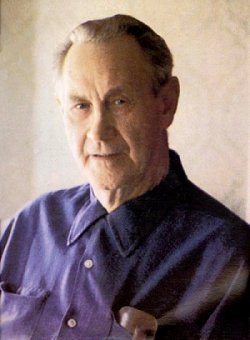

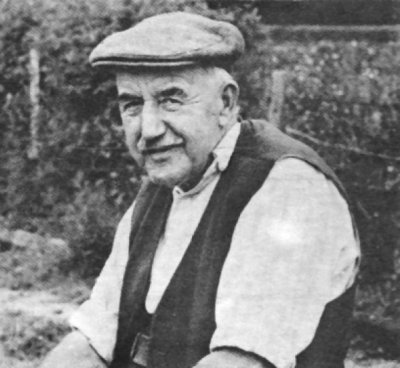

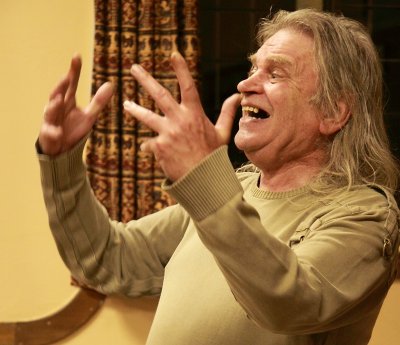

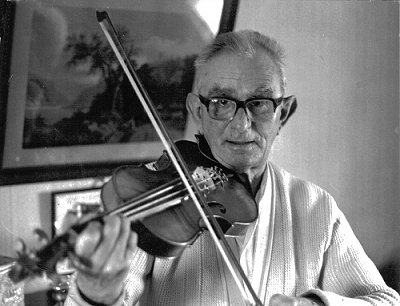

Stephen Baldwin: Stephen James ('Stevie') Baldwin was born in Hereford in 1873, but soon after, his parents took the family back to Newent in Gloucestershire where the family came from. He worked as a plate-layer on the Great Western Railway for all of his working life. During the First World War he served in France with the 13th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment, the 'Glosters', and was invalided out after the Battle of the Somme. He inherited his father's fiddle, which Charlie Baldwin had bought at a music shop in Hereford, and he in turn passed it on to his own son Charles, who played it until he was forced to give up when rheumatism stiffened the first finger of his left hand. Stephen himself subsequently obtained another fiddle which in later life hung on the wall by the chimney in his cottage at Upton Bishop.

Stephen Baldwin also became involved with Morris dancing when, at Christmas one harsh winter in about 1897, Thomas Bishop, the 'King' of the morris at Bromsberrow Heath, fetched him over from Newent to stand in for the regular musician, concertina player Bill Rudds, who was ill. Stephen was so taken with the dance that he taught it to a side he himself raised at Mitcheldean, where he was living at the time. They danced for two or three seasons until the turn of the century.

Stephen Baldwin also became involved with Morris dancing when, at Christmas one harsh winter in about 1897, Thomas Bishop, the 'King' of the morris at Bromsberrow Heath, fetched him over from Newent to stand in for the regular musician, concertina player Bill Rudds, who was ill. Stephen was so taken with the dance that he taught it to a side he himself raised at Mitcheldean, where he was living at the time. They danced for two or three seasons until the turn of the century.

Stephen's second wife Grace played the piano, and would accompany him when he played the fiddle in the evenings - to discourage him from playing in the pub, it is said, though perhaps maliciously, as many a traditional fiddler also enjoyed playing at home if there was a pianist in the family to play along with. As well as playing the fiddle and singing popular songs, Stephen Baldwin was also involved in a local carol singing party.

These recordings have a significance beyond the music they contain, of course. Not only do they provide a wonderful snapshot of the playing of a fine traditional fiddler with a repertoire which predates both the age of recording and broadcasting, and exposure to the influences of more formal forms of music and musicianship; they also preserve the interface between the more static and conservative forms of country dance music for interactive sets of dancers (typically in triple time) which were already moribund, and more dynamic and innovative forms of music for solo (and fundamentally exhibitionist) dancers (typically in duple time, and syncopated). These latter are exemplified by hornpipes and the step dancing they were inextricably associated with.

1 - Napoleon's March

played by Stephen Baldwin - fiddle

from "Here's one you'll like, I think" (MTCD334)

Napoleon's (Grand) March was popular with traditional musicians throughout the British Isles, and versions have also been recorded from Billy Conroy (whistle) in Northumberland and Billy Pennock (fiddle) of Goathland on the North Yorkshire Moors. George Tremain (melodeon) of Yorkshire recorded it on a 78 rpm record in the 1950s.

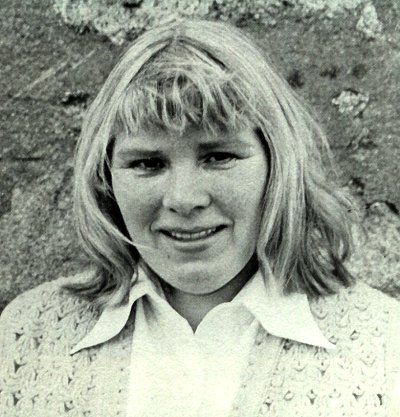

Audrey Smith: The senior member of the session, at over 80, Audrey is also amongst the most dedicated - and certainly the most punctual of all of us! She has a large repertoire of unusual songs and is still learning new ones, and singing better than ever before.

Of herself, Audrey writes: I worked professionally for ten years with John Timpany. We were multi-instrumentalists but greatly enjoyed singing unaccompanied. When we split, I gave John my guitar and soon found myself using only my brass-reeded English concertina as accompaniment to some songs. I started a club in Northamptonshire which celebrated its 25th birthday in 2004, and a very eclectic one at the multicultural centre in Wellingborough.

Moving to Stroud in 1991, I supported the Railway Club until it folded, and have been associated with the Fleece session since it started. It has always been attended by mostly unaccompanied singers, and I found that this style gave me greater freedom in the presentation of songs.

2 - The Death of Parker (Roud 1032)

sung by Audrey Smith

from Songs From the Golden Fleece (MTCD335-6)

Ye Gods above protect the widow

And with pity look down on me;

Help me, help me out of trouble

And through this sad calamity.

Parker was a wild young sailor,

Fortune to him did prove unkind,

Although he was hanged up for mutiny,

Worse than him was left behind.

Chorus:

Farewell Parker, thou bright angel,

Once thou wast old England's pride.

Although he was hanged up for mutiny,

Worse than him was left behind.

Young Parker was my lawful husband,

My bosom friend whom I loved so dear;

Though doomed by law he was to suffer,

I was not allowed to come near.

At length I saw the yellow flag flying,

The signal that my true love was to die,

The gun was fired that was required,

To hang him all on the yard-arm so high.

The boatman did his best endeavour

To reach the shore without delay,

There I stood waiting, just like a mermaid,

To carry the corpse of my husband away.

At dead of night when all was silent

And thousands of people lay fast asleep,

Me and my poor maidens beside me

Into the burying ground did creep.

With trembling hands instead of shovels

The mould from his coffin we scratched away,

Until we came to the corpse of Parker

And carried it off without delay.

A mourning cart there stood a-waiting

And off to London we drove with speed,

And there we had him most decently buried

And a sermon preached over him indeed.

I first sang this as a solo with John Timpany's whistle accompaniment and probably got it from The Wanton Seed. I liked it because The Nore - where the mutiny took place - is not that far from where I then lived.

Gardiner collected the song from Mr W Rundle, landlord of the Farmer's Inn, St Merryn, Cornwall, in 1905, but the text in the book has been augmented from two Hampshire versions.

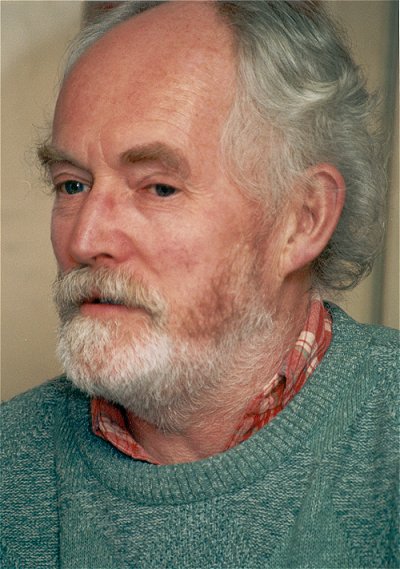

Bob Bray: writes 'I began singing in my native East Anglia, listening to the classic singers of the East Coast: Sam Larner and Harry Cox, then Joseph Taylor and latterly Walter Pardon from Norfolk. Settling in Leicester after my itinerant twenties I, sang with Jon Scaife who accompanied me on guitar and cittern for over ten years, adding songs from America, Ulster and even some new pieces to my repertoire before moving to Stroud where, after a spell singing harmony with Sue Burgess, I began to look again at my unaccompanied singing style and roots in the southern English tradition.

I have developed a singing style that is direct, but with more ornament than many English singers, and am increasingly focused on the direction the singing is taking in these interesting times. I have always enjoyed small singing sessions and during the 1970s began the Leicester Traditional Music Workshop, which ran for 10 years or so at the Bricklayers Arms. A few years after arriving in Stroud I started the Stroud Singing Session at the Woolpack, that has now settled at the Golden Fleece.

The atmosphere of a small session where singers can talk and sing in a way that may more closely mirror the natural home of the songs is always my favourite setting for singing. I can sing all the songs I wish and feel comfortable to experiment with new ideas for the songs. Perhaps it is the love of drink and good company that confirms this singing ambience as ideal.'

3 - The Flowers of Bermuda

(composed by Stan Rogers)

sung by Bob Bray

from Songs From the Golden Fleece (MTCD335-6)

It was five short hours from Bermuda's Isle

In a fine October gale

When the cry it came now "There are breakers dead ahead."

From the collier nightingale.

No sooner had the Captain turned around

No sooner had the Captain turned around

When came the rending crash below

Hard on her beam end, groaning, went the Nightingale

And overboard her mainmast goes.

"Oh Captain, are we all to drown now?"

Came the cry from all the crew

"For the boats are smashed; how are we all now to be saved,

They are stove-in through and through."

"Oh are you brave and hardy collier men?

Or are you blind now and cannot see?

For the Captain's gig still lies before you whole and sound

And it shall carry us away."

But when the crew were all assembled there

And the gig was prepared for sea,

It was seen there were but eighteen places to be manned

And nineteen mortal souls were we.

Then cries the Captain "Now do not delay

Nor do you spare one thought for me.

My duty is to save you all now if I can;

See you return swift as can be."

Now there are flowers on Bermuda's Isle

Beauty shines on every hand;

There is laughter, ease and drink there for every man -

But there is no joy for me.

For when we reached the wretched Nightingale

Such an awful sight was plain,

For the Captain, drowned, was tangled in the mizzen chain;

Smiling bravely beneath the sea.

He was the Captain of that Nightingale,

Twenty one days from Clyde in coal.

He could smell the flowers of Bermuda in the gale,

As he died on the North Rock shoal.

A song from the pen of Canadan, Stan Rogers, who clearly had a fascination with the sea and sailing. I heard this song on an LP in the 1970s and 'straightened it out' for singing unaccompanied. A fragment of a story woven round the self-sacrifice sometimes found at sea, and reflected ironically in the heroic death of Stan Rogers, who died rescuing others in an air crash.

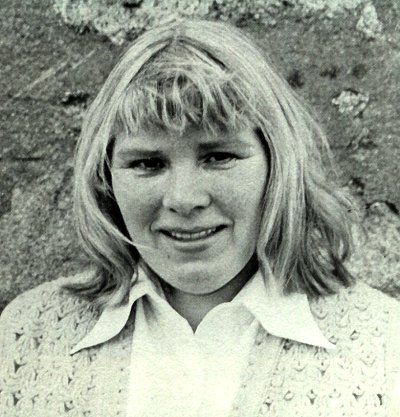

Lizzie Higgins: Lizzie was born in the Guest [ghaist = ghost] Row of Aberdeen, an ancient side street which was to vanish under desperately needed slum clearance in the 1950s. Her parents were settled Travellers: Donald ('Donty') Higgins, a piper of great repute, and Jeannie Robertson. In the house also was her uncle Isaac ('Seely') another fine piper.

In 1953, Hamish Henderson came to record her mother, Jeannie Robertson for the School of Scottish Studies, and Jeannie was thus launched on a singing career which brought her international fame, but although Lizzie was also recorded singing with her mother, she refused all invitations to perform in public, being not just shy but unwilling to be seen as competing with Jeannie. There was more to it than that, for as Lizzie later said: "The folk scene claimed Jeannie. I didnae want it tae claim me". Lizzie held out until 1967, when the late Peter Hall persuaded her to sing at the Aberdeen Folk Song Festival.

She made an immediate impact on the audience, for singer and performance were both remarkably composed, to the delight of her highly supportive parents from whom she had learned most of her repertoire. From such a beginning she became greatly in demand throughout Scotland, England and Wales, but there were catches: her audiences at first consisted of 'Jeannie's followers' who expected to hear her perform her mother's repertoire, and Lizzie was persuaded to produce a solo record on such lines, with which she was little pleased. She determined to succeed thereafter on her own terms, with her own songs and style of singing, attributing both largely to her father.

4 - The Beggarman (Roud 119, Child 280)

sung by Lizzie Higgins

from In Memory of ... (MTCD337-8)

A beggar, a beggar cam ower the lea

He was asking lodgings for charity

He was asking lodgings for charity

He was asking lodgings for charity

"Wid ye loo a beggar man-o,

Lassie, wi ma tow row ray?"

"A beggar, a beggar, I'll never loo again.

I had a dochter and Jeannie was her name.

I had a dochter and Jeannie was her name;

She's run awa with the beggar man-o,

Laddie, wi ma tow row ray."

"I'll bend my back an I'll boo my knee

An I'll pit a black patch oer my ee

And a beggar, a beggar they'll tak me to be

An awa wi you a'll gang-o,

Laddie, wi ma tow row ray."

"Oh lassie, oh lassie, yer far too young

An ye hannae got the cant o the beggin tongue.

Ye hannae got the cant o the beggin tongue

An wi me ye winnae gang-o,

Lassie, wi ma tow row ray."

She's bent her back and she's booed her knee

An she's put a black patch oer her ee.

She has kilted her skirts up aboun her knee

An awa wi him she's gan-o,

Laddie, wi ma tow row ray

"Yer dochter Jean is comin ower the lea;

She's taken hame her bairnies three

She has yin on her back, ay, another on her knee

An the other yin is toddlin hame-o,

Lassie, wi ma tow row ray."

Very widely sung in Scotland, and all but one of Roud's 67 instances are from here. [Extraordinarily, though, Lizzie is the only singer of whom he has a recording]. Cilla Fisher and Artie Tresize sing a version in Cilla and Artie Greentrax CDTrax 9050 (1979).

The lively tune first appear in the Balcarres Lute Book (1690-1700), with tune plus words in Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius in 1725 (see the remarkably detailed accounts in Nick Parkes and John Purser's 2006 CD-Rom of James Oswald's Caledonian Pocket Companion). The words alone also appeared in Allan Ramsay's highly influential Tea Table Miscellany in 1724, and together with the equally popular thereafter, Jolly Beggar, has been attributed to James V (1512-1542), the hanger of Johnny Armstrong, who reputedbly wandered his kingdom in disguise, often as a beggar, as The Guidman of Ballangeich, in his sympathy with the common people, (although this may have been simply a liking for low life). His short life and troubled reign would not have left him much spare time for such sojourning, nor his marriages to two wives, the second bearing him the future, tragic Mary Queen of Scots (and France). Lizzie said this was the first song she learned from her father, when she was aged 4, and was a genuine 'pipe folksong'.

5 - Johnnie Sangster (Roud 2164)

sung by Lizzie Higgins

from In Memory of ... (MTCD337-8)

O aa the seasons o the year

When we maun1 work the sairest,2

The hairvest is the foremost3 time

An yet it is the rarest.4

Chorus:

For you, Johnny, you Johnny,

You, ma Johnny Sangster,

I'll trim the gavel5 o ma sheaf

For you're the gallant bandster.6

We rise as seen as morning licht7

Nae craiters8 can be blither.9

We buckle on oor finger steels10

An followed oot the scyther.

For you, Johnny ...

A mornin piece11 to line oor cheek12

Afore we get the forder.13

Wi cloods14 a blue tabacca reek15

We then set oot in order.

For you, Johnny ...

The sheaves are risin thick an fast

An Johnny he maun16 bind them.

The busy group for fear they stick,

They cannae look behind them

For you, Johnny ...

I'll gie ye bands that winnae17 slip;

I'll pleat them weel and thraw18 them

And sure they winnae tine19 the grip,

Hooever weel ye draw20 them.

For you, Johnny ...

"I'll lay ma leg oot ower21 the sheaf

An draw the band sae handy,

Wi ilka strae's as straucht's a rash22

And that will be fine dandy."

For you, Johnny ...

If e'er it chance to be ma lot

To be a gallant bandster,

I'll gar23 him wear a gentle24 coat

An bring him gowd25 in handfu's.

For you, Johnny ...

But Johnny he can please hissel;

I widdnae wish him blinket.26

Sae aifter he has brewed his ale,

He can sit doon and drink it.

For you, Johnny ...

A dainty cooie27 in the byre

For butter and for cheeses,

A grumphie28 feedin in the sty

Will keep the hoose in greases.

For you, Johnny ...

A bonny ewie29 in the bucht30

Would help to creesh31 the ladle

An we'll get ruffs o canny woo32

Would help to theek33 a cradle.

For you, Johnny ...

1 must; 2 hardest; 3 most important; 4 most exciting; 5 gable = base; 6 one who binds sheaves; 7 soon as morning light; 8 creatures/people; 9 happier; 10 finger stalls = leather or cloth protective guards; 11 snack; 12 mouth; 13 get to work again; 14 clouds; 15 smoke; 16 must; 17 will not; 18 twist; 19 lose; 20 tighten; 21 out over; 22 every straw as straight as a rush; 23 have, make; 24 decent; 25 money; 26 hindered; 27 smart looking cow; 28 pig; 29 good quality ewe; 30 sheep-fold; 31 grease; 32 tufts of wool left on whin bushes; 33 thatch, line, thicken.

For a song still so widely sung in Scotland, it's very surprising to find only 12 Roud entries - only one of which was a sound recording; the 1951 BBC disc of a Mrs Mearns, from Aberdeen. Isla St Clair gives a spirited version on Tatties & Herrin': The Land, Greentrax CDTrax 145 (on which, interestingly, the male bandster's perspective is also given in Band o' Shearers)

Before the reaping machine transformed harvesting from the 1850/60s onwards (together with the later binder and the combine harvester), harvesting teams consisted of scythers, followed by gaitherers (such as the song's singer) who would lay out on straw bands the bundles of cut grain, which the following bandster would convert into sheaves to stook for drying. The teams (first recorded in 1642) employed by the larger farms were professional and paid by results - hence the need for speed and efficiency. Thistles made the life of such workers a misery - thus the need for finger protection. The singer appears so infatuated by her bandster that she says she is willing to work extra hard, by dunting the base of her bundles in order to make them easier for him to handle and stack. Wages were good for these teams and her dream of sharing a self-sufficient smallholding with her intended was not unrealistic.

A song Lizzie learned from her great-uncle Geordie Mhor ['Big Geordie'] Robertson of New Deer, himself a famous horseman, who was a frequent visitor to the house in the 1950s. Geordie had been a friend of Gavin Greig's, playing the pipes in Greig's highly popular stage plays Prince Charlie and Mains's Wooin'.

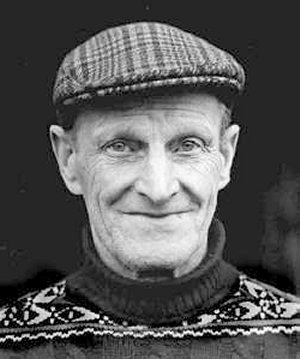

Jumbo Brightwell: William 'Jumbo' Brightwell was one of Velvet Brightwell's eleven children, born in 1900 in Little Glemham. It was there he met an old sailor called Jumbo Poacher from whom he got his nickname. After the war in 1919 he returned to Leiston where he worked as a bricklayer's labourer and then eventually started at Garrett's and served twenty years as a shunter before retirement. He rarely missed a Saturday night in the Eel's Foot, where he would go with his father and brother, Bob. He learned his songs from local and visiting singers as well as, of course, from his father Velvet, although he told Keith Summers that The False Hearted Knight came from his mother. He was also a champion quoits player and he would hear songs when playing at other pubs in the area.

6 - The Drowned Lover (Roud 185, Laws K18)

sung by Jumbo Brightwell

from A Story to Tell (MTCD339-0)

Now it was of a wild young couple

In Scarborough did dwell

She loved a young sailor and he loved her as well

He had promised to be married

When back he did return

But instead of getting married

He found a watery tomb.

For the ship set sail from Scarborough

For the ship set sail from Scarborough

From Scarborough to the bay

When the winds did blow and whistle

And those billows loud did roar.

The winds did blow and whistle

And those billows loud did roar.

And it tossed these poor sailors

All on an early shore.

Well some of them had sweethearts

And some of them had wives.

Which caused these poor sailors

To swim out for their lives.

While some they managed to reach shore

As it happended to be so

But this unfortunate sailor

He found a watery tomb.

As soon as the news reached Scarborough,

To the beach this fair maid went.

Ringing of her hands and she tore her hair

Like a lady in great distress

"Crying come ye cruel billows

It's come roll my love on shore.

That I might view his features,

Kiss his fond lips once more."

As she was walking from Scarborough,

From Scarborough to the bay

She saw a drowned sailor all on the beach did lay

She so nimbly stepped up to him

But immediately did stand

She knew it was her own true love

By the mark upon his hand.

She kissed him, she fondled him,

She kissed him a thousand and oe'r

She kissed him, she cuddled him

A thousand times or more.

She kissed and she cuddled him

A thousand times or more

Then she kissed his cold lips.

Broken hearted she died.

In a churchyard in Scarborough

Is where this couple lie

Embracing one each other

In such a loving way

Come all you men and maidens

Who do this way pass by

Think you of this loving couple

Who under here do lie.

"There you are."

A well-known song in both England and Scotland, but it doesn't appear to have crossed the sea to Ireland. Almost all versions mention Scarborough (or Stowbrow) as the setting of the tragedy.

Other recordings on CD: Sam Larner (Topic TSCD 652); Frank Verrill (Topic TSCD 662); Harry Cox (Topic TSCD 512D); Harold Smy (Veteran VTC5CD).

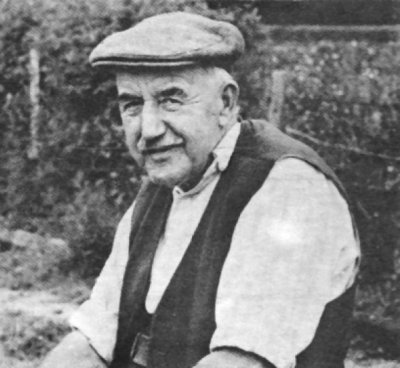

Fred List: Frederick John List was born at World's End Farm, Saxtead, in 1911 and was brother to Billy List. He sang lots of songs with many coming from his father, Harry List, who was recorded by Peter Kennedy for the BBC in 1951.

Fred List: Frederick John List was born at World's End Farm, Saxtead, in 1911 and was brother to Billy List. He sang lots of songs with many coming from his father, Harry List, who was recorded by Peter Kennedy for the BBC in 1951.

He learned to play melodeon as a young teenager, teamed up with George Scott, and started playing around the pubs - Framlingham Railway was their regular Saturday night spot. In later days Fred became the house musician at Blaxhall Ship and was featured on the 1974 Transatlantic LP The Larks they Sang Melodious.

Keith Summers wrote: 'The first person I recorded [on his new Uher tape recorder] was Fred List, singing and playing the accordion. Some of the best accordion / melodeon playing I've ever heard.

The only reason that I got recordings of Charlie Whiting in the event was that Fred List gave him a right bollocking, a few days after Charlie had given me hard time in the pub. He later told me, Fred List, that the whole village, the whole pub, thought that was very poor of Charlie and well out of order and they told him so.'

7 - The Barndance

played by Fred List - melodeon

from A Story to Tell (MTCD339-0)

Fred's barn dance is Felix Burns' Woodland Flowers - a tune known at Blaxhall as The Shit Cart Polka (at least according to Alan Waller, so possibly / certainly unreliable, but one shouldn't forget he was an early visitor, and Steve Pallant used to call it that, too). A prolific composer, Felix Burns (1864-1920) was Jimmy Shand's favourite composer; he also wrote The Dancing Dustman and Shufflin' Samuel.

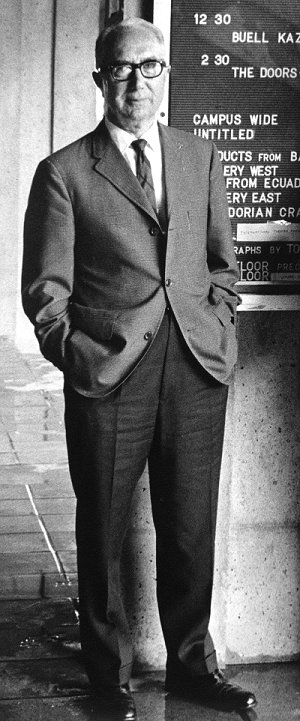

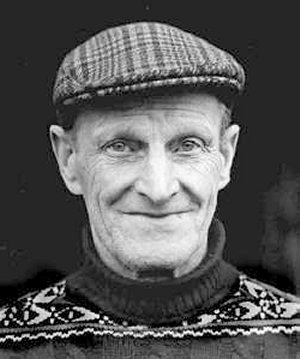

Buell Kazee: The Reverend Buell Kazee was celebrated for the estimable 78s he had recorded for Brunswick in the late 1920s and he had later made a record for Folkways that he did not like. Later he worked as a Baptist minster, first in the coal fields and then in Winchester and Lexington. When Mark Wilson wanted to record him in the 1970s, Buell himself was continually ambivalent about recording: 'I think he worried that getting swept up in the swirl of the music business again might run the risk of distracting him from his spiritual duties. He was quite exacting about the quality of his performances and I imagine he worried about this strain of intense perfectionism within himself.'

Buell Kazee: The Reverend Buell Kazee was celebrated for the estimable 78s he had recorded for Brunswick in the late 1920s and he had later made a record for Folkways that he did not like. Later he worked as a Baptist minster, first in the coal fields and then in Winchester and Lexington. When Mark Wilson wanted to record him in the 1970s, Buell himself was continually ambivalent about recording: 'I think he worried that getting swept up in the swirl of the music business again might run the risk of distracting him from his spiritual duties. He was quite exacting about the quality of his performances and I imagine he worried about this strain of intense perfectionism within himself.'

8 - The Inconstant Lover (Roud 454)

sung by Buell Kazee

from Meeting's a Pleasure Vol 1 (MTCD505-6)

To meeting, to meeting, to meeting goes I

To meet loving William he is coming by and by

To meet him in the meadow, it's all my delight

I can walk and talk with him from morning 'til night.

For meeting is a pleasure and parting is grief

An inconstant lover is worse than a thief

A thief will only rob you and take what you have

But an inconstant lover will bring you to the grave.

Your grave it will rot you and turn you to dust

There's not one in twenty that a poor girl can trust

They'll kiss a poor maiden, it's all to deceive

Not one in five hundred you'll dare to reveal.

If I am forsaken, I am not foresworn

And you're badly mistaken if you think I'd do more

I'll dress myself up pretty in some high degree

And I'll pass as lightly by him as he does with me.

Come young men and maidens, take warning by me

Never put your affection on a green willow tree

The top it will wither and the roots they will rot

And if I'm forsaken, I know I'm not forgot.

Although Rev Kazee sometimes consulted folk song books to fill out his texts, Mark Wilson believes that he learned the core of this version as a boy. It's a member of The Cuckoo is a Pretty Bird family of songs - a family which is itself mainly constructed from floating verses. As is usual in such cases, the individual songs have a bewildering array of titles; this American one is most usually known as Handsome Molly, and has almost 100 Roud entries, all from North America except for a score from Ireland, where it's usually called Going to Mass Last Sunday. Rev Kazee's final line seems unique to him, as may be the utterly splendid tune.

The Dixon Sisters: Faye Ginn, Wanda Rhodes, Carol Foster, Geneva Boyd, and Mildred Tucker - this remarkable group of harmonizing sisters, who are now settled with their families along both sides of the Ohio River, often get together to sing in church or to cheer up inmates in the local nursing homes. Generally, they sing gospel numbers or popular fare (e.g., Sentimental Journey) familiar to their audiences, but they also remember a range of older songs from their father, John Henry Dixon, who came from Wolfe County and regularly sang to them as kids.

09 - My Little White Hat (Roud 691, Laws E17)

sung by The Dixon Sisters

from Meeting's a Pleasure Vol 2

(MTCD505-6)

I used to wear my little white hat, my horse and buggy fine

I used to court those pretty girls and always called them mine

I courted them for beauty, their love for me was great

And when they seed me coming, they'd meet me at the gate.

When I laid down the other night, I dreamed a noble dream

When I laid down the other night, I dreamed a noble dream

I dreamed I was a rich merchant called up some golden stream

I woke up broken hearted in Logan County jail

Looking all around me, found no one to go my bail.

Down came the jailer about ten o'clock

The keys all in his pocket, he brushed against the lock

"Cheer up, cheer up, my prisoner,"

I thought I heard him say

"You're just going down to old Moundsville,

just seven long years to stay."

Down came my mother, ten dollars in her hand

Saying, "Oh, my dear Willie, I've done the best I can.

The jury's found you guilty, the judge says you must go

Way down to old Moundsville, just seven long years to stay."

Down came my true love, about two o'clock

Saying, "Oh, my dear love, what sentence have you got?"

"The jury's found me guilty, the judge says I must go

Way down to old Moundsville, just seven long years to go."

I'm sitting on this railroad, just waiting for the train

I'm going down to old Moundsville, to wear the ball and chain

I'm going down to old Moundsville, so, true love, don't you cry

Just pass around the bottle, boys, and let her all pass by.

This lyric cluster shows up across North America in an astonishing variety of forms, ranging from the compressed (Hobart Smith's Hawkins County Jail) to the extended, as the Dixons nicely provide here. The earliest American version of the full song apparently appears in John Lomax' original Cowboy Songs and Cox's Folk-songs of the South provides several versions of Logan County Court House quite comparable to the Dixon's, acquired from their dad. Moundsville, also in West Virginia, is the location of its state penitentiary, a fact their father, coming from Wolfe County, would have recognized whereas his daughters, raised further to the west, seem a bit uncertain about the name.

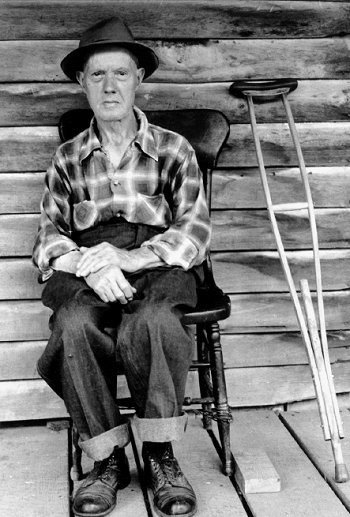

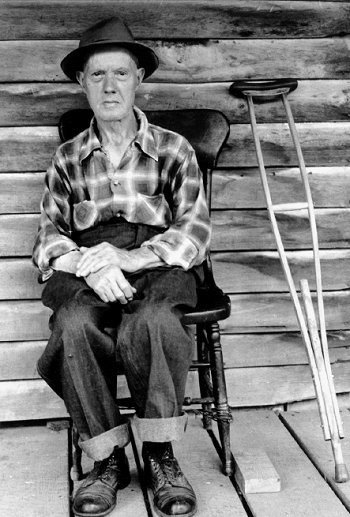

Perry Riley: was Buddy Thomas' cousin and a fine country fiddler in his own right. All his life he had wandered the South in search of work, living at different times in West Virginia and Arkansas. The day we met him, he had injured himself in an accident and was waiting for a bus to convey him to an old folks' home, where he died not long after. Despite all this, he was very animated and cheery that day.

10 - I Know Somebody's Going to Miss Me When I'm Gone

sung by Perry Riley

from Meeting's a Pleasure Vol 3 (MTCD507-8)

Not so long ago one morning,

Not so long ago one morning,

Mother called me to her bed

And she threw her arms all around me,

"Listen to these words", she said.

"Son, I'm going to leave you

but you won't be left alone

If you put your trust in Jesus

after He has carried me home."

Chorus:

It won't be very long before

I get to go see my mother, she's went on.

I know somebody's going to miss me

I know somebody's going to miss me when I'm gone

I know somebody's going to miss me when I'm gone.

When my life on earth is ended

and they lay me beneath the sod

I expect to meet my mother somewhere

around the throne of God.

I never will forget that morning

when they laid her beneath the sod

I thought my heart was breaking

but I put my trust in God.

Ever since that fateful morning

Christ has been my hopes every day

And I know sometime I'll be with him,

I'll be with him there to stay.

After we had recorded a number of wonderful fiddle tunes, Perry asked if he could sing a few selections, including this one, of which he stated proudly, "I composed that one myself." Indeed, though undoubtedly based upon some preexistent prototype, I am not familiar with anything quite like this (beyond distant similarities to the Carter Family's Will You Miss Me When I'm Gone?). These many years later, I can still vividly see Perry listening to the playback of this number on the headphones and smiling broadly at the results as I packed the rest of my equipment into the car (we were very late to a dinner engagement with one of Buddy's sisters).

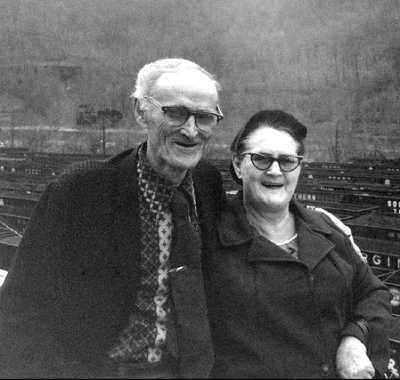

J P Fraley: J P and Annadeene were born in the early depression to small town families during an era when traditional music could be readily encountered locally, although its character was rapidly shifting. Neither J P nor Annadeene was ever confined to an exclusive diet of family-based music, as often proves the case for musicians who possess very large stocks of old songs. J P's home music background derived largely from his father, Richard, and his circle of friends, who were country fiddlers in the mold of Alva Greene (no recordings of Richard are known to exist, unfortunately). In his teenage years J P and gravitated to more 'progressive' forms of music: specifically, to tight harmony groups in the mold of the Sons of the Pioneers, and much enjoyed playing 'western music' and, in later years, liked to listen to Stephane Grappelli and Eddie South.

It is important to appreciate that, although a good detail of indubitable 'folk music' could be readily found throughout the Fraleys' home region, it coexisted, quite happily in this period, with more uptown forms of music. A few examples: the great jazz violinist Stuff Smith was raised in Portsmouth, Ohio; the skilled fiddler Jimmie Wheeler (from whom J P and Roger Cooper learned many tunes) played bass and guitar in popular music orchestras where he learned to follow their complex charts; a relative of J P's named 'Big Foot' Keaton played excellent swing fiddle on a local radio program.

11 - The Yellow Rose of Texas

played by J P Fraley, fiddle; Bert Garvin, banjo; Keith Garvin, jew's harp; Danielle Fraley, guitar; Doug Chaffin, bass.

from Meeting's a Pleasure Vol 3 (MTCD507-8)

This well known tune originated on the minstrel stage c.1850 and it and sundry parodies frequently appear in songsters of the period. It retained some popularity in 'hillbilly' music circles and as atmospherics in western movies (eg, the eponymous vehicle starring Roy Rogers, who, as it happens, was raised just down the road from Ray Hilt's boyhood farm). It received a substantial boost in popularity in the 1950s through an oddly martial recording by Mitch Miller (often credited with singlehandedly degrading the quality of American popular song through his A&R work at Columbia Records). The caprice that the 'yellow rose' of the song depicts the Emily Morgan who allegedly distracted Santa Ana before the battle of San Jacinto appears to be a twentieth century fabrication.

Weenie Brazil: One of the most important aspects of these CDs is that they contain the only known recordings of Weenie (Selphinus) Brazil. To say that he was a fabulous singer must surely be a gross understatement. He was recorded by Hamish Henderson on the Blairgowrie berryfields, July/August 1955, andit's a tragedy that he was not recorded again ... and quite inexplicable that these wonderful recordings have been lying, unheard, in the School of Scottish Studies Archive for 52 years!

12 - Son Come Tell it Unto Me (Roud 564, Laws P18)

sung by Weenie (Selphinus) Brazil

from Down by the Old Riverside (MTCD345-6)

"Where have you been the whole night long,

Son come tell it unto me?"

"I've been in the search of an old game cock,

That flew from tree to tree."

"How come the blood on your arm sleeve,

Son come tell it unto me?"

"That is the blood of my own brother dear,

That lays over under yonder tree."

"What did you kill your own dear brother for,

Son come tell it unto me?"

"Because that he killed the two turtle doves

That flew from tree to tree."

"What will you do when your father comes to know

Son come tell it unto me?"

"I'll sail away to another foreign shore

Where my face he'll never, never see."

"What will you do with your own dear wedded wife

Son come tell it unto me?"

"I'll dress her up in a jolly sailor's suit,

And take her on board the ship with me."

"What will you do with your two tender babes,

Son come tell it unto me?"

"I'll leave them home with their own granpa,

For to bear them company."

"What will you do with your houses and your land

Son come tell it unto me?"

"I will leave them all to my own father,

For to maintain my little family."

"Now tarry sailor when will you turn this way again

Son come tell it unto me?"

"When the moon and the sun both shine as one,

And that you will never, never see."

This was also sung by Lemmie, Alice, Danny, Tom and Angela Brazil, so it could be considered the family's favourite song. One of the most striking things about these recordings of a significant number of singers from one family, is that - given the slight variations of text and melody from one singer to another - it seems fairly clear that all family members got their songs from one source; most likely their parents, or even grandparents.

This is a very popular song with 236 Roud entries, of which 59 are sound recordings. The great majority are from the USA (148 entries) and Scotland (46 entries). Only 4 other singers from England are named.

Angela Brazil: like her father, Weenie, Angela was recorded in the berryfields of Blair, by Hamish Henderson, but this recording was made by Peter Kennedy, in the same year and location.

13 - The Poor Smuggler's Boy (Roud 618)

sung by Angela Brazil

from Down by the Old Riverside (MTCD345-6)

My father and mother once happy did dwell

In a neat little cottage not far from the shore

My father had to venture his life on the sea.

For a keg of good brandy, he was bound for folly.

The night had been dark and the wind it blew high,

And lightning flashed round us; we was far from the shore.

Our main mast riggings it blew into the waves,

And causes my father a watery grave.

I jumped overboard in the midst of the sea;

I clapped his cold hands and more lively was he.

I was forced for to leave him sinking in the salt sea.

I swum to a plank and I gained my shore;

Sad news to my mother, my father's no more.

My mother brokenhearted, with sorrow she died.

For I'm now left to wander." cried the smuggler's poor boy.

"I will build up a boat, and I'll keep up his trade,

Until it does cause me a watery grave."

Songs about orphans wandering the world in search of succour are pretty common, but this is quite a rare example, with only 42 Roud instances, all from the south of England. It appeared in several broadsides, and probably dates from the first third of the 19th century. It may well have been published without a suggested tune, since all the versions I've heard use different ones; Angela employs the Long Lamkin tune here - maybe because her family had been travelling in Scotland for most of her early life. Her final stanza may well be unique.

A similar version called Our Ship Lost its Rigging was known to several of the nearby Smith Family in the Cheltenham area, and Norfolk's Walter Pardon sang a very complete version - all are on other Musical Traditions CDs.

Lemmie (Lementina) Brazil: There were 15 brothers and sisters in that generation of the Brazil family of which the younger members were recorded. Their parents were William Brazil, born in Devonshire, and Pricscilla Webb, born in Cornwall. The family had lived in London for some time, then travelled in southern England and Lemmie was born "outside Southampton in Devonshire", following which they spent some 27 years travelling in Ireland, where most of the younger children were born, before returning to England and settling in Gloucester in 1919.

Lemmie (Lementina) Brazil: There were 15 brothers and sisters in that generation of the Brazil family of which the younger members were recorded. Their parents were William Brazil, born in Devonshire, and Pricscilla Webb, born in Cornwall. The family had lived in London for some time, then travelled in southern England and Lemmie was born "outside Southampton in Devonshire", following which they spent some 27 years travelling in Ireland, where most of the younger children were born, before returning to England and settling in Gloucester in 1919.

The details of Lemmie's playing place it fairly and squarely in the English tradition as we know it from other players recorded since the war, and is particularly reminiscent of Norfolk melodeon players like Percy Brown, George Craske and Bob Davies. Like theirs, her playing is melodic, pacey, stressed on the offbeat and slightly dotted, and honed to the needs of the step-dancer. And, like them, she often dispenses with pick-up notes and stresses and dwells on the first note of a tune - whether in common time or 6/8 - before switching the stress to the offbeat until the end of the phrase.

14 - Lemmy's Stepdances Nos 1 & 2

played by Lemmie Brazil - melodeon

from Down by the Old Riverside (MTCD345-6)

In her version of the Bristol Hornpipe (the second tune here) Lemmie plays a couple of bars of the rather monotonous standard second strain, but uses them to launch a completely new medodic phrase. The use of the first few bars of a familiar tune as the launching pad for something quite different is typical of Lemmie's approach to her material, but unlike many other fine traditional English musicians she doesn't make do with repetitive rhythmic phrases when she doesn't have part of a tune, but extrapolates new melodic phrases. Thanks to her natural musicality, her innate understanding of her repertoire and genre, and her preference for certain intervals these are often more interesting than the 'missing' phrases. Although a free treatment of melody is common among traditional musicians in England, it is usually the product of rhythmic invention or dittography, and genuine melodic invention like Lemmie's is rare.

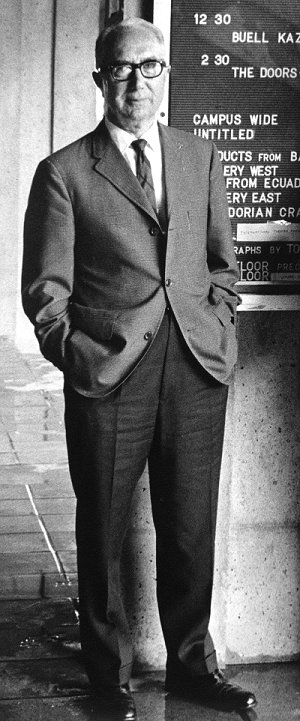

Ken Langsbury: 'I was born in 1938, in Ealing, West London. My father was Henry (Harry) Langsbury, a Gloucestershire man working at Vanden Plas, Kingsbury, as a Coach Painter when he met my mother. She was Harriet Harwood (Queenie) Brown, who lived in Northolt and worked as a barmaid in The Target pub when she met Dad.

The family (Mum, Dad, older brother Lionel and I) moved to Cheltenham after a neighbouring house up the road was bombed in 1940. This was the time when my Auntie Kath and Uncle Frank were married in Northolt church, and the Battle of Britain dog fight was going on in the sky above them when they came out of the church.

We moved in with my Dad's family, Gran, Grampy, Great Auntie Rose and Auntie May, in Cheltenham - but Mum couldn't stick it. She got a job as barmaid in The King's Head, Lower High Street, which was an old coaching inn, with a yard at the back where lorries parked over night. Also in the yard was a stable occupied by Jack Sivell, Rag & Bone Merchant, and a small cottage which the landlord let us live in, in exchange for Mum working. Much to the disgust of Great Auntie Rose, who said no decent people ever went down that end of town.'

15 - The Bishop of Worcester

told by Ken Langsbury

from And Then it Happened! (MTCD348)

When King George went to Worcester, once upon a time, he'd gone there to see the Bishop. And when he gets to the Bishop's front gate he sees a big brass plate which says 'Here lives the Independent Bishop of Worcester'. "Well, I don't think much of that," says the King to himself, and in he goes.

"I understands you calls yourself the Independent Bishop of Worcester." "That's right, Sire, because I don't give way to no man." "Well, I don't think much of it," says the King, "and I'll tell you what we'll do - we'll go off to London on Wednesday morning, and I shall ask you three questions. And the first question - 'How long would it take me to go all the way around the world?' And the second question - 'How much am I worth, right down to the nearest farthing?' And the last question - 'What am I thinking at the exact moment as we be speaking?' And if you can't answer all of they three questions, you will no longer be known as 'the Independent Bishop of Worcester'."

"I understands you calls yourself the Independent Bishop of Worcester." "That's right, Sire, because I don't give way to no man." "Well, I don't think much of it," says the King, "and I'll tell you what we'll do - we'll go off to London on Wednesday morning, and I shall ask you three questions. And the first question - 'How long would it take me to go all the way around the world?' And the second question - 'How much am I worth, right down to the nearest farthing?' And the last question - 'What am I thinking at the exact moment as we be speaking?' And if you can't answer all of they three questions, you will no longer be known as 'the Independent Bishop of Worcester'."

Next morning was Tuesday morning, and the Bishop was up early; he hadn't slept a wink all night. A very worried man he were indeed to be sure, and he goes out into his back garden and starts pacing up and down his garden path. And there were an old gardener feller there, a-working nigh. "Anything up, Governor?" "Nope", says the Bishop, and continues pacing up and down his garden path. After about twenty minutes, this here gardener feller whoas him up again and says, "You sure there's nothing wrong, Governor?" "Well, you've been a good and faithful servant to me all these years, so I'll tell you." "Is that all?" says the gardener - that was after he'd finished telling him, like. "Does the King know you very well?" "Nope, I only met the gentleman for the first time last night." "Well, I'll tell you what we'll do. I'll get up tomorrow morning, I'll put on your clothes, and off I'll go to London, to Buckingham Palace, and I shall answer all of they three questions for you, because I'm not a bit worried about it."

So that's what they does. Come Wednesday morning, he gets up early, put on his governor's clothes, and off he trots to London - Buckingham Palace - and goes into this great big room, and there's the King sitting up at the far end, with all his courtiers a-seated all around him.

"Right," says the King, "first question: how long would it take me to go all the way around the world?" "Thee must go by the sun, Sire," he says, "and that'll take you exactly twenty-four hours." "Very good!" says the King. "Ha-ha!" says all the courtiers - "That's one up to the Bishop!" "Yes", says the King, "but how much am I worth, right down to the nearest farthing?" "Nothing at all!" he says, "Nothing at all! There's only ever been one man that were ever worth anything, and he were sold for thirty pieces of silver, so by that reckoning, thee aren't even worth a farthing." "Very good!" says the King. "Ha-ha!" says all the courtiers - "That's two up to the Bishop!" "Yes", says the King, "but what am I thinking at this exact moment?" "Ah-ha," he says, "that's the easiest. Thee be thinking as how I'm Bishop of Worcester, but I'm not, I'm only his gardener!" And then they chopped his head off.

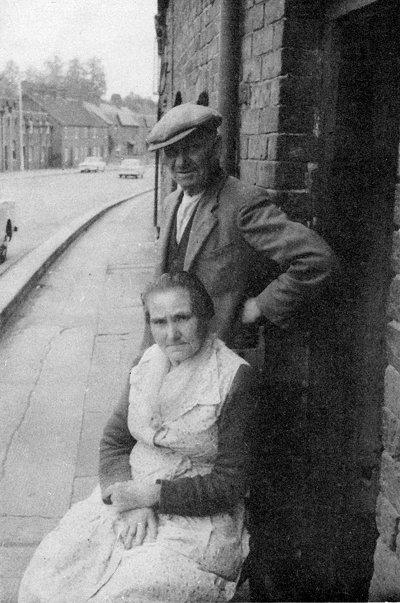

May Bradley: was born 19 January 1902 to Romany parents named Robert and Esther Smith. In the 1911 census, aged only nine years, her parents gave her birthplace as Clipstone, in Glamorganshire, although in later life she claimed to have been "bred, borned and raised just 'round 'ere [i.e. the vicinity of Ludlow] ... Well, Monmouthshire ... Chepstow in Monmouthshire I were born." Her own and many other Romany families travelled extensively around the west Midlands and into the near areas of Wales, wherever the opportunity for gainful employment led them. May Bradley was descended from a long line of singers within her immediate family, and from close contact with other travellers over an extended period additionally absorbed many items into her repertoire.

A chance meeting at the age of fifty-seven with the song collector Fred Hamer, with whom she established a special rapport, resulted in the survival of much of the older portion, at least, of her repertoire, now to be heard on this release. That she knew a number of more recently composed songs is clear, but her aesthetic sense was unambiguous: "I don't like mixing the old uns with the new ones."

A chance meeting at the age of fifty-seven with the song collector Fred Hamer, with whom she established a special rapport, resulted in the survival of much of the older portion, at least, of her repertoire, now to be heard on this release. That she knew a number of more recently composed songs is clear, but her aesthetic sense was unambiguous: "I don't like mixing the old uns with the new ones."

16 - On Christmas Day (Roud 1078)

Sung by May Bradley

From Sweet Swansea (MTCD349)

On Christmas day it happened so

Down in those meadows for to plough

As he were ploughing all on so fast

Up came sweet Jesus hisself at last

"Oh man, oh man, what makes thou plough

So hard upon our Lord's birthday?"

The farmer answered him with great speed

"For to plough this day I have got need."

Now his arms did quaver through and through

His arms did quaver, he could not plough

For the ground did open and loose him in

Before he could repent of sin.

His wife and children's out of place

His beasts and cattle they're almost lost

His beasts and cattle they die away

For ploughing on old Christmas day

Now his beasts and cattle they die away

For ploughing on our Lord's birthday.

Fred Hamer used more than one tape recorder and recorded in several different situations; thus you will find a good deal of extraneous noise on a few tracks, and one or two inferior quality recordings. Possibly the worst example of this - so very sadly - is what may be her best recorded performance. This version of On Christmas Day is badly over-recorded and with a dreadful din going on outside, or in the next room. I have reduced the noise much more than is usually desirable so you can hear something of a truly cracking performance - and one which includes the chilling 'His arms did quiver through and through' verse - which rather makes the point of the song - missing from the better recording, which also fades out at the final line.

Roud shows 11 entries for this carol, but all are either by May or her mother, Esther Smith. These are the only two sound recordings. Sharp heard it in Armscote, Warwickshire, in 1910, as did Alice Gillington among Gypsies in the New Forest; neither named their sources.

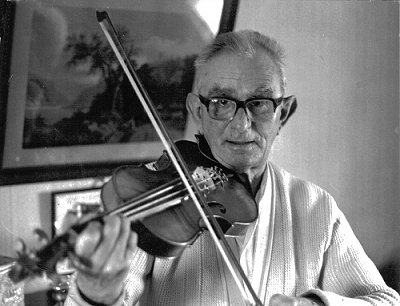

Art Galbraith: Arthur Galbraith - born 1901 in Hawkins County in the hills of northeast Tennessee - like his forebears, grew up on the James River, but he moved off the farm and found a career in the post office. Playing for square dances, and for friends in the warm kitchen of the old family farmhouse, he honed and perfected his art, and preserved his family's musical gift. Many of these tunes are unusual, many of them old, and all of them played in a distinct regional style that can be traced back in southwest Missouri over one hundred years. It is a delicate, stately, lilting style that has seldom been commercially recorded, and it has a special beauty that suggests why the old-timers in southern Missouri still call it "violin music."

17 - Paddy on the Turnpike

played by Art Galbraith - fiddle

from Dixie Blossoms (MTCD509)

The unexpectedly truncated phrasing suggests that this must have been a family tune; most recorded versions (which are legion) are regular in their meter. Early settings of "Paddy" are generally in G minor; when recast in A major (as here), the tune becomes so different that some variants adopt a parody title, Paddy on the Railroad.

Roger Cooper: was born on January 19, 1949 and raised in sundry parts of Lewis County, Kentucky, a beautiful region of rolling hills arrayed along the broad Ohio River. Prototypical Appalachian hills and hollows cluster thickly in  Lewis County as soon as one leaves the river and many of the simpler but evocatively lonesome hill tunes of central-eastern Kentucky continued to be cherished by the amateur fiddlers who worked the little farms scattered through this rolling terrain.

Lewis County as soon as one leaves the river and many of the simpler but evocatively lonesome hill tunes of central-eastern Kentucky continued to be cherished by the amateur fiddlers who worked the little farms scattered through this rolling terrain.

The frequent interchange between the two sides of the Ohio River gave rise to one of America's most distinguished fiddle repertories, well exemplified by the blend of tunes to be heard on the present record. Roger Cooper grew up at the tail end of this great regional tradition and had the great fortune to have been tutored in the music by one of its finest practitioners, the late Buddy Thomas, who died in 1974 at the age of omly thirty-nine.

18 - Pretty Little Indian

played by Roger Cooper - fiddle

from Essence of Old Kentucky (MTCD310)

This melody may represent an old West Virginia tune, but virtually all of its current popularity traces to the late Curly Ray Cline, who fiddled for Ralph Stanley for many years and who recorded the piece on Rebel 1506. It is to be presumed that Buddy Thomas (Roger' source) learned the tune in descent from Cline's performance. It bears certain affinities to the widely distributed Little Widow and may represent a recomposition of those strains.

Morgan MacQuarrey: was born July 29, 1946 to Jack and Zina MacQuarrie of Loch Ban, Inverness County, Cape Breton. This little grouping of farms lies about a mile west of the hamlet of Kenloch on the north shore of Lake Ainslie. At the time of these recordings he was only in his early 50s - some 20 to 30 years younger than the typical old-time fiddler. To put that another way, he is the same age as the typical post-war folk revivalist. Most of his contemporaries in Cape Breton looked down on traditional music as backwoods, hick, and irredeemably old fashioned, turning instead to Rock'n'Roll or Nashville Music.

Morgan MacQuarrey: was born July 29, 1946 to Jack and Zina MacQuarrie of Loch Ban, Inverness County, Cape Breton. This little grouping of farms lies about a mile west of the hamlet of Kenloch on the north shore of Lake Ainslie. At the time of these recordings he was only in his early 50s - some 20 to 30 years younger than the typical old-time fiddler. To put that another way, he is the same age as the typical post-war folk revivalist. Most of his contemporaries in Cape Breton looked down on traditional music as backwoods, hick, and irredeemably old fashioned, turning instead to Rock'n'Roll or Nashville Music.

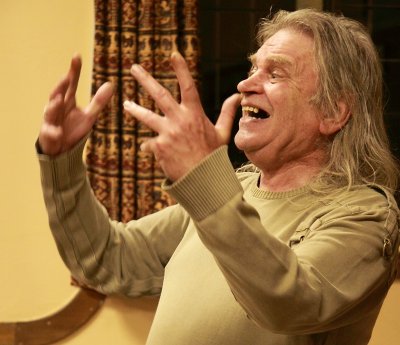

In total contrast the teenage Morgan took to hanging out with a crowd of local reprobates 20 years or more older than himself, to whom the old fashioned music was inextricably associated with what he calls "cutting up and blaggarding". He is politely scathing about the 'identity' approach ("… 'Celtic' this and 'Celtic' that…") - in contrast Morgan and his mentors "…were just trying to have a good time".

19 - The Warlocks, Bog an Lachan - strathspeys; Tarbolton Lodge, Little Jack's - reels.

played by Morgan MacQuarrey - fiddle

from Over the Cabot Trail (MTCD511)

Certain pairings and triples of tunes remain fairly constant, such as the Warlocks/Bog an Lachan pairing. As Morgan explains the matter, these partial associations reappear because a Cape Breton fiddler rarely conceives of a medley as a sequence of discrete tunes (indeed, few of the older musicians know names for most of their tunes), but instead considers its unfolding in developmental terms: the whole must progress through a gradually accelerating sequence of complimentary moods. Thus the conclusion of a specific tune will 'call for' some designated form of contrasting continuation, whether it be a specific melody or any of a family of acceptable substitutes.

Morgan finds formal recording work rather aggravating because he and Gordon have decided that they should fix these choices ahead of time, rather than merely allowing the fiddler to select the continuation as whimsy dictates.

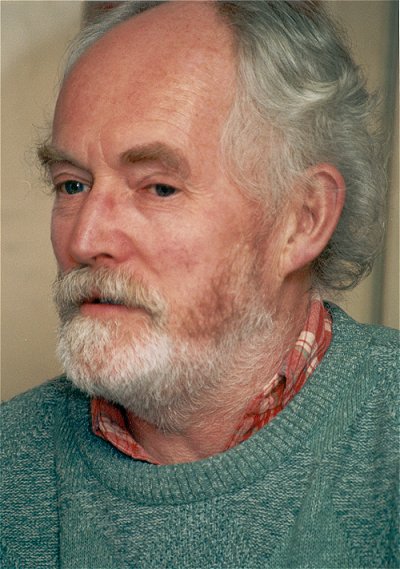

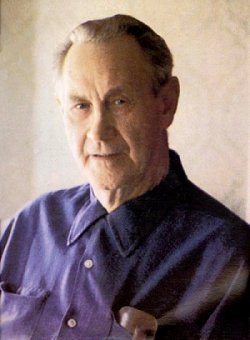

Nimrod Workman: was born in Martin County, Kentucky, in 1895 and died in Knoxville, Tennessee, aged 99 years, in 1994, although he spent most of his life, as a miner, in Chattaroy, West Virginia. He was only 14 years old when he started work in the Howard Collieries coal mines in Mingo County, WV, where he quickly became active in union politics. In the early 1920s he worked alongside the activist Mary Harris 'Mother' Jones and in 1921 took part in a massive strike, later known as the Battle of Blair Mountain, where some 10,000 - 15,000 miners took on the Logan County, West Virginia, coal bosses; the latter being backed by the police and, later, the US Army. It is estimated that some one million rounds were fired at the miners during this attempt to establish unions. No wonder Nimrod Workman turned out to be the man that he was! In later years he worked to bring compensation to the miners who, like himself, had contracted black lung disease. And during all this time, he sang.

20 - Oh Death (Roud 4933)

sung by Nimrod Workman

from Mother Jones' Will (MTCD512)

Chorus:

Chorus:

Oh Death, Oh Death,

Won't you spare me over for another year?

What is that I can't see

Icy hand's got a hold on me?

I am Death, come here for your soul.

Leave your body and leave it cold.

Chorus.

I am Death and I wish you well

And I hold the keys to Heaven and Hell.

Chorus.

Gonna take the skin

Right off of your frame

And the earth and the worm

Both have their claim.

Chorus.

Death, Oh Death, consider my age

Please don't take me in this stage.

Chorus.

It now seems almost mandatory to begin any note about Oh, Death with a comment about the early English song Death and the Lady (Roud 1031). But, as Mark Wilson correctly observes, they are not the same song. The present song may be entirely American in origin but there is no doubt that it is fairly old and widely spread.

Although variants of this song are fairly well known, the versions which have most influenced the revival are Dock Boggs' great version on Folkways 9025 and Lloyd Chandler's Conversation with Death on Rounder 0028. Nimrod dearly loved to 'act out' his songs with his hands and facial expressions (a policy he probably borrowed from the little medicine shows that often visited the mountain communities in the 'twenties and 'thirties). Performed in this manner, Oh Death proved popular in his performances for revivalist audiences in later years.

Fred Whiting: was born in 1905 at Kenton in Suffolk, a mile or so north-east of Debenham, and getting on for five miles to the west of Framlingham, the son of John Whiting and (Gertrude) Annie, née Taylor. Born into a family with a deep involvement in every aspect of traditional music in the area, Fred learnt his first songs from his father, and when young played the fiddle for his Uncle Jim and his dancing doll, while his cousins Bill and Charlie Whiting were a melodeon-player and prize-winning step-dancer respectively.

He started off playing the mouthorgan, but couldn't afford the constant replacements. When he was 16 Fred saved up until he could afford a violin and a bow. He was unusual as a traditional musician in several respects: he was  left-handed and played the fiddle as a conventional right-handed player would but left-handed, so the strings were the 'wrong way' round, describing himself as a 'fiddling freak' in this respect. He also spent many years in Australia and picked up tunes there, thus having a broad repertoire beyond the East Anglian material he picked up in his early years.

left-handed and played the fiddle as a conventional right-handed player would but left-handed, so the strings were the 'wrong way' round, describing himself as a 'fiddling freak' in this respect. He also spent many years in Australia and picked up tunes there, thus having a broad repertoire beyond the East Anglian material he picked up in his early years.

He also took the trouble to learn to read music - and picked up more tunes from various printed sources, most notably early on from Honeyman's Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor. This in itself would raise the cry from some that he wasn't a traditional musician at all, and certainly Cecil Sharp wouldn't have considered him so, but whereas he is unusual in becoming musically literate, he is not unique in this respect. Fred was in every respect a 'fiddler,' playing tunes learned from older musicians, in particular Harkie Nesling, from whom he got several tunes, despite their playing styles being rather different. This of course was the usual way for traditional musicians, and was commonplace.

21 - Will the Waggoner

played by Fred 'Pip' Whiting - fiddle

from "Old-time hornpipes, polkas and jigs" (MTCD350)

"An old Gypsy hornpipe" - this tune and its name does not seem to occur anywhere else. It shares elements of its melodic content with similar 'one-off' tunes and songs in Fred's repertoire and may be local - or even Fred's - takes on other tunes. It's possible that Fred bestowed his own names on the tunes: do the name of this tune and Fred's description of it point towards Gypsy fiddler Billy Harris?

Bill Smith: was born in 1909, one of ten children, nine of whom survived into adulthood. The family lived in the village of Diddlebury, about five miles from Ludlow in the area known as Corve Dale. He was a farm worker (and briefly a farmer) all his life. The recordings of Bill were all made by his son, Andrew, over the period 1979 - '83. They are, most importantly, perhaps the only available example of the completely unmediated repertoire of an ordinary countryman, from the centre of England, in the middle of the 20th century. Andrew wasn't a song collector, and didn't choose what to record and what to omit - he just recorded what Bill remembered … songs, recitations, stories, jokes.

22 - Ram She Ad-a-Dee (Roud 1212)

sung by Bill Smith

from A Country Lfe (MTCD351)

Now I once did court a bonny lass and a bonny lass was Sue

Now I once did court a bonny lass and a bonny lass was Sue

Her name was Tittle-ma-tarra-ma-ti and mine was Tarra-ma-too

I once did go a courtin' her when her old man was at home

He says "If I catches you here again, by gad I'll tittle your ... "

Chorus:

Ram she ad a dee, ad a dee, ad a dee

Ram she ad a dee ay

Ram she ad a dee, ad a dee, ad a dee

Ram she ad a dee ay.

So Kitty and I we made it up as a ladder I should bring

We fixed it up to her window and by gad it was just the thing

We tittled and chaffed and chaffed and laughed until at last by gum

My foot slipped through her window and I fell and I caught me ...

Chorus

They took me to the doctor's shop and there I told me case

By gad I couldn't help but laugh when I looked the chap in the face

I thought I was making a fool of him, but a fool of him by gum

I thought he was making a fool of me when he turpentined me ...

Chorus

So they wheeled me home in a wheelbarrow and they wheeled me home with care

The people they all laughed and they stared when they brought me there

'What ever have you been doin' now?' said my brother Tom

I said 'I've been a courting and I fell and I caught me ...

Chorus

Not a very widely collected song, with only 13 Roud entries ... but some well-known singers: the Copper family; Harry Green; Bill House; and Pop Maynard - this latter being the only other available on CD (MTCD309-10 or 401-2).

Harry Langston: was born in Burnley, Lancashire, in 1948. 'The Burnley that I knew was typical of Lancashire cotton towns, and even in the early 1950s its appearance had changed little since the late 1900s, when much of the poetry was written. I first came across the Lancashire dialect poetry when I was a teenager in the 1960s, and, as they say, it seemed to leap off the page! A lot about it seemed familiar to me. Some of the stories were like those I'd heard around me as I was growing up, and many used a form of speech that I knew well.' Harry wrote the wonderful tunes to all these poems.

23 - Posey Joe by Joseph Cronshaw

sung by Harry Langston

from Dear Gladys, Dear Gertie ... (MTCD352)

Aw've a bonny little garden

Aw've a bonny little garden

Reet full o' pratty flowers

An' when it's leet till late at neet

Aw spend some happy hours;

Wi' reet good will aw tak' mi spade

An' delve an hour or so,

An' then aw sit, an' smook a bit

An' watch my posies grow.

There's scores o' folk would give a lot

To live a life like mine.

Aw'm reet content for blessings sent

Bi' th' weather weet or fine.

Old Sol may hide his face awhile,

But then, yo' see, I know

It tak's some rain as weel as sun

To make my posies grow.

There's lots o'bees an' butterflies

Come sippin' fro' each bell;

There's music sweet, morn, noon an' neet,

Comes fro' yon little dell.

There's throstles pipin' loud an' clear,

While finches, sweet an' low,

Join in a chorus as I sit

An' watch my posies grow.

Aw've polyants an' gree' house plants,

Grand roses, too, as well,

Tall hollyhocks, an' phlox, an' stocks,

Far more nor aw con tell.

Neaw, should yo' ever come this road,

Just ax for Posey Joe;

Aw'll tak' yo' reawnd my bit o' greawnd,

To see my posies grow.

Joseph Cronshaw, 'The Ancotes Bard', strikes me as an enterprising and sparky character. As a lad he hawked salt from a donkey and cart, eventually becoming a grease refiner and salt merchant on a large scale. As well as a sideline of keeping a stud of donkeys on Blackpool beach, he performed energetic 'turns' on stage. These were developed from studies of characters he encountered on the Salt Wharf at Anchotes.

When we moved to Barden, I remember the impact that suddenly having a garden made on us all - my father liked his lupins, dahlias and marigolds. Cronshaw perfectly encapsulates the joy of a treasured 'bit o' greawnd' in this delightful poem. I cannot lay any claim whatsoever to be a gardener (my wife is the expert in our house) but I do recognise the passion in others - and I do seem to get a lot of requests to sing it.

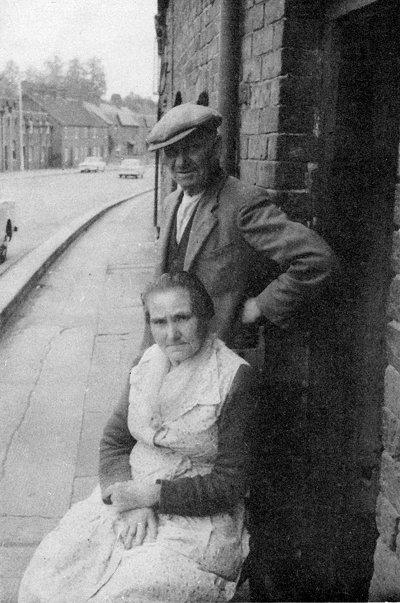

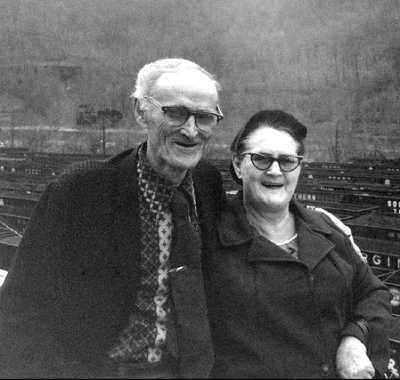

Sarah Makem: was born with the 20th century, on High Street, Keady, Co Armagh, the daughter of Tommy Boyle, a plumber and tinsmith, and Margaret Greene, a noted singer, and like most people in the town, as soon as she was old enough to leave school, she went to work in one of the linen mills that thronged the lush valleys of the Clay and the Callan. Sarah was one of seven children, whose father died young, and her mother had it hard enough to rear her family, working as a winder, for which she could earn eleven shillings a week with a sixpenny bonus, for she was the best worker in the mill.

Sarah loved to sing; she sang when she was happy and she sang when she was sad, and she sang when she was angry - you could always tell what mood she was in by the way she sang: "If you hear me singing loud, don't come in!" she'd warn. She acquired songs from anybody who came within her orbit, and if she didn't get all the words first time, she would make a point of checking them, sometimes making notes for herself.

Sarah's emergence into the limelight is usually attributed to her rendition of As I Roved Out (Seventeen Come Sunday) being used as the theme tune for the radio programme of the same name in the early 1950s.

24 - County Galway Girl (Roud 9307)

sung by Sarah Makem

from As I Roved Out (MTCD353-5)

Ara hush, mavourneen, hold your tongue

And I'll praise the girl that's fair and young

Sure, me thoughts are on her night and day

Since first I met her in Galway.

Chorus:

For she is me fancy, neat and trim

She's rosy cheeks and dimpled chin

And her footsteps light as any squirrel

She's me rattling County Galway girl.

If you seen her on Saint Patrick's Day

Preparing whiskey for the day

And her hair tied back with ribbons green

You would think she was an Irish queen.

Chorus.

And if I could only her caress

In Irish style I'd her address

And I'd change her name to Mrs Tyrell

But still she'd be my Galway Girl.

Chorus.

The only other instance of this song in Roud is the 1952 BBC sound recording by Peter Kennedy of John MacLaverty, in Belfast. The first line of his version is transcribed in the BBC Index as "Ah be there hush, and hold your tongue" and is evidently a rendering of the Irish "Bí i do thost" or "Be quiet".

The song appears in Harding's Dublin Songster under the title The Galway Girl and with the subtitle 'Sung by Paddy Clarke at Crampton Court'. John McCall's Scrapbook, mentioned in connection with The Irishman, has a copy of this version.

25 - 'Twas in the Month of January (Roud 175, Laws P20)

sung by Sarah Makem

from As I Roved Out (MTCD353-5)

It was in the month of January

It was in the month of January

The hills were clad in snow

When over hills and valleys

My true love she did go

It was there I spied a pretty fair maid

With a salt tear in her eye

She had a baby in her arms

And bitter she did cry.

"Oh cruel was my father

That barred the door on me

And cruel was my mother

This dreadful crime to see

Cruel was my own true love

To change his mind for gold

And cruel was that winter's night

That pierced my heart with cold.

"For the taller that the palm tree grows

The sweeter is the bark

And the fairer that a young man speaks

The falser is his heart

He will kiss and embrace you

'Til he thinks he has you won

Then he'll go away and leave you

All for some other one.

"Now all ye pretty fair maids

A warning take by me

And never try to build your nest

On top of a high tree

For the leaves they will all wither

And the branches will decay

And the beauties of a false young man

Will all soon fade away."

This is considered by many to be Sarah Makem's greatest contribution to the annals of folksong. In a way, it's surprising that it should be so revered, since it's only really two verses followed by two floaters. But Sarah's emotional yet controlled singing of a truly glorious tune ensures that it will be long remembered.

It treats one of the oldest themes in traditional song - the story of a young girl betrayed and abandoned by her lover and cast by cruel parents into the snow. Herbert Hughes prints a fragmentary version of this song, called The Fanaid Grove, in Irish Country Songs. Vol.1. For an augmented text see Kennedy, Folk Songs of Britain and Ireland.

It's not a particularly well-known song, with only 33 Roud entries; it goes by many titles, but none is more prevalent than the others. It has been sung all over these islands, and North America, but is most common in Ireland, with singers Geordie Hanna, Paddy Tunney, Tom Lenihan, and Dan MacGinty being named as well as Sarah.

26 - Miss Jenny (Roud 23422)

sung by Sarah Makem

from As I Roved Out (MTCD353-5)

Oh there was a gay shepherd came courting Miss Jenny,

He was neat, tall and handsome, was comely and fair.

He went to forest, his flocks for to view them;

She borrowed men's clothing and followed him there.

Coat, waistcoat and trousers, as fine shoes and stockings,

A hat on her head and a cane in her hand.

And as he was walking, she boldly stepped forward

And kindly saluted this handsome young man.

"Good morrow, gay shepherd, >the weather seems misty;

Show me the straight road to the banks of Drumwer" (?)

"Oh yes, noble stranger, how far have you rangèd?

I ne'er saw as nice a lad crossing this earth."

"What come over you, Johnny - you don't know your Jenny?

Sure, these are men's clothing I borrowed from home.

Yes these are men's clothing I borrowed from neighbours,

In case some wee lassie would take ye awa'."

A song which neither we, nor Steve Roud, have ever encountered before - and it has only just been discovered by ITMA amongst their Diane Hamilton recordings.

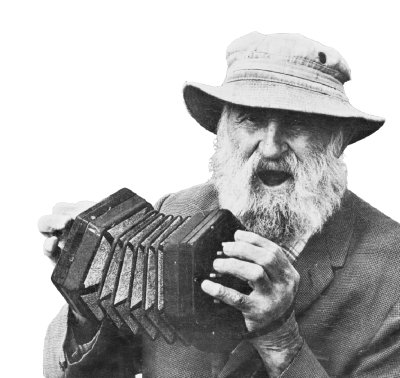

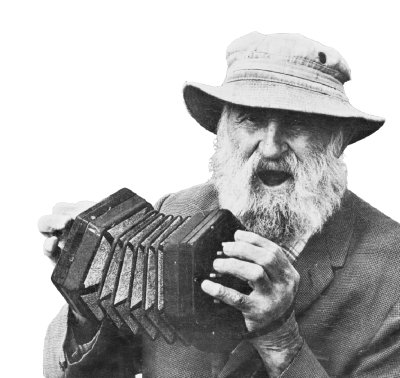

'Dooley' Chapman: Albert George 'Dooley' Chapman (1892-1982) was born in Coborrah, New South Wales, and in later years he lived in Dunedoo, a larger farming town nearby. Chapman played the concertina for rural dances in a wide part of his district in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

'Dooley' Chapman: Albert George 'Dooley' Chapman (1892-1982) was born in Coborrah, New South Wales, and in later years he lived in Dunedoo, a larger farming town nearby. Chapman played the concertina for rural dances in a wide part of his district in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

His was a musical family; his father and an uncle played violin, and his brothers and sisters played violin, concertina, and piano. Dooley began playing concertina at the age of ten, and began playing for local house parties and dances. In his younger years he was a farmer, but he later built concrete silos and sheep dips for a living. As bush dances were dying out in the 1920s, Chapman extended his playing days by teaming up with his sister Grace on piano. He played for dances as late as World War II; such dances returned briefly as feelings of Australian patriotism rose during the war.

27 - Old Dan Tucker (Roud 390)

played by Albert 'Dooley' Chapman - anglo-concertina

from House Dance CD-ROM (MTCD251)

This American minstrel tune was popularized by Dan Emmett and the Virginia Minstrels in 1843, who spread the tune worldwide - there are 144 Roud entries. Played as a breakdown in its original form (a tune in common time where the emphasis falls on the second and fourth beat), it has clearly made a number of melodic and rhythmic changes before coming to Chapman.