Article MT013

Veteran Morris dancer, singer, musician ...

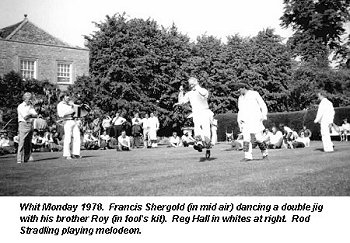

Francis Shergold resigned as Squire of the Bampton Morris in November 1995, after an astonishing 60 years as dancer with the side - 45 of those as Squire. He was awarded the Gold Medal of the EFDSS in 1996 (see our report), as had the former Squire, 'Jinky' Wells, some 38 years before. With the rebirth of MT, it seemed an appropriate time to commission an article on Francis, as he assumed the mantle of Honorary President of the side. At 79, he continues to participate in all the side's activities, including the dancing at times, and we have every expectation that he will continue to do so throughout the coming seasons.

Keith Chandler's article follows Francis' career through to the 1980s, and he has suggested that I might like to add a post-script to continue the story, from a personal perspective, through to the present day. I hope that this will be added to the piece in the not too distant future.

Rod Stradling

Perhaps the best-known morris dance side of the English South Midlands is that belonging to the small town of Bampton, on the western side of Oxfordshire. While some participants and outsiders have claimed a performance history of up to six hundred years, we can more realistically confirm activity spanning a quarter of that period.

Perhaps the best-known morris dance side of the English South Midlands is that belonging to the small town of Bampton, on the western side of Oxfordshire. While some participants and outsiders have claimed a performance history of up to six hundred years, we can more realistically confirm activity spanning a quarter of that period. 11 and

11 and 15 and

15 and  17

17

Among the most prominent handful of performers during the present century is Francis Shergold, born 31st January 1919, who recently retired following a fifty year spell as leader of one of the three currently active Bampton teams. Despite his total integration into the social and cultural life of the town, his father was not a local man. Francis' brother Roy, himself a longtime dancer and, later, fool with the side, thinks that their father, George, was born in Sevenoaks, Kent. 2 On the distaff side, however, the family is keyed into an extensive inter-village network of morris dancers, dating back to the early nineteenth century, at least. Francis' great grandfather (see below) was Robert Lock (1819 - 1907), youngest of three brothers who were dancers in the side at Field Assarts, a hamlet then within the Forest of Wychwood.

2 On the distaff side, however, the family is keyed into an extensive inter-village network of morris dancers, dating back to the early nineteenth century, at least. Francis' great grandfather (see below) was Robert Lock (1819 - 1907), youngest of three brothers who were dancers in the side at Field Assarts, a hamlet then within the Forest of Wychwood. 16

16

Although I continue to interview and record material on the Bampton morris tradition, the majority of what follows was collected directly from Francis, his brother Roy, sister Ruth, and mother Louise in 1980, during a heady period when I effectively lived in Bampton and was recording information on almost a daily basis. In addition to more formal interviews, generally in the homes of informants ( 8 and

8 and 10 are examples here), much of what I collected was gleaned in casual (though often directed and steered) conversation, often in the Shergold side's headquarters of the time, The Eagle pub in Church View. In fact, I practically lived in the cottage two doors from that pub for a year. As a result, even where portions of the following paragraphs do not appear in quotes they are generally close paraphrases, written down as soon as possible after they occurred, so that this remains essentially Francis' own story told in his own words (in italics), augmented by those of his immediate family.

10 are examples here), much of what I collected was gleaned in casual (though often directed and steered) conversation, often in the Shergold side's headquarters of the time, The Eagle pub in Church View. In fact, I practically lived in the cottage two doors from that pub for a year. As a result, even where portions of the following paragraphs do not appear in quotes they are generally close paraphrases, written down as soon as possible after they occurred, so that this remains essentially Francis' own story told in his own words (in italics), augmented by those of his immediate family.

When Francis was a young boy the family lived at the toll-bridge at Swinbrook, near Eynsham, on what was then the main Oxford to Cheltenham Road. Later they moved to Standlake, where brother Roy was born in 1925, ending up in Bampton a few weeks before Whitsun in 1932. Shortly afterwards, on leaving school, Francis arranged for a job at Weald Manor, but since he couldn't start until the horses were brought inside during the autumn, he worked for a while at Constables, a bakery, delivering the bread. 'I got fed up with that. Well, I couldn't stand the smell of the dough.' He then took another job until September, after which he started at the Manor, continuing there for the remainder of his working life. Initially he worked under the head gardener, later becoming head gardener himself. 10

10

By the date of Francis' first involvement with the morris dancers, the recent problems caused by personality conflicts - which resulted in two distinct morris dance sides appearing for a number of years from 1927 on - had been resolved. 12 and

12 and  13

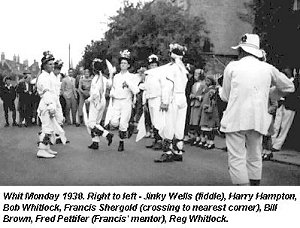

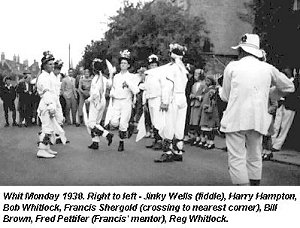

13  During the 1930s there certainly were Whit Mondays when a second team made an appearance, but it was that led by fiddler William Nathan 'Jinky' Wells (1868-1953) who annually kept the tradition going without fail.

During the 1930s there certainly were Whit Mondays when a second team made an appearance, but it was that led by fiddler William Nathan 'Jinky' Wells (1868-1953) who annually kept the tradition going without fail.

Francis remembers watching the morris team practise prior to Whitsun outside the Malt Shovel pub (now a garage), flanking the town square. Many of the local kids used to watch the dancers and some would be invited to have a dance in the set, perhaps while a dancer went inside for a pint 10 (other men, including Ted Lay and Arnold Woodley, have told me this also). The Shergolds knew the Wells family and it was 'Jinky' who asked him to join. Francis' grandfather, 'a very strict man', was well aware of the problems caused by the amount of alcohol they were given while out dancing, and commented to Francis' mother Louise, "You're not going to let him join the Morris."

10 (other men, including Ted Lay and Arnold Woodley, have told me this also). The Shergolds knew the Wells family and it was 'Jinky' who asked him to join. Francis' grandfather, 'a very strict man', was well aware of the problems caused by the amount of alcohol they were given while out dancing, and commented to Francis' mother Louise, "You're not going to let him join the Morris." 8

8

But she did anyway, and Wells taught Francis to dance. By this date, however, 'he was a bit blind and he couldn't always see if you were going wrong. He would show you certain movements, but mostly you had to pick it up by watching the other dancers ... Jinky used to say, "I don't mind being blind so much, but I don't like being deaf - it affects my playing. I can't hear the fiddle." He was a grand old boy.' There were effectively two cliques within the team when he first danced. The older dancers didn't always talk or socialise with the younger ones. One veteran, Reg Whitlock, 'was so quiet you thought he was miserable ...  The one I always got on best with was Fred Pettifer. He had a good sense of humour and was friendly. I based myself (i.e. dancing style) on him. I never told him that ... The older ones used to do the jigs - Bill Brown, Reg Whitlock ... I learned the jigs very early on. But it wasn't like today. [Nowadays] the older ones will let the young ones have a jig.'

The one I always got on best with was Fred Pettifer. He had a good sense of humour and was friendly. I based myself (i.e. dancing style) on him. I never told him that ... The older ones used to do the jigs - Bill Brown, Reg Whitlock ... I learned the jigs very early on. But it wasn't like today. [Nowadays] the older ones will let the young ones have a jig.' 10

10

His first Whit Monday was 1935. He began in the morning by carrying the coats on a strap slung over the shoulder. 'We don't do it now. I was glad to go round with the morris.' He was already dressed in dancing whites, so during the afternoon Jinky said to him, "Well boy, I think it's about time you had a dance now." 1 'I danced through the afternoon. Well, as many as I could get into.'

1 'I danced through the afternoon. Well, as many as I could get into.' 7 ; After the day's dancing had ended all those involved returned to Wells' house to divide the money among the adult members. Jinky put nine bowls on the table - one each for musician, six dancers, fool and cake carrier - and the takings were split into equal portions. Afterwards, there were a few coppers left over on the table and Wells told them to give them to Francis. In addition, 'They all gave me some of their share. Two bob (i.e. ten pence) each or something. Might have been only five pence (i.e. half the previously mentioned amount). I got twelve bob that first year ... Probably gave it to my mother to buy a new pair of boots.'

7 ; After the day's dancing had ended all those involved returned to Wells' house to divide the money among the adult members. Jinky put nine bowls on the table - one each for musician, six dancers, fool and cake carrier - and the takings were split into equal portions. Afterwards, there were a few coppers left over on the table and Wells told them to give them to Francis. In addition, 'They all gave me some of their share. Two bob (i.e. ten pence) each or something. Might have been only five pence (i.e. half the previously mentioned amount). I got twelve bob that first year ... Probably gave it to my mother to buy a new pair of boots.'  The kit he first danced in was 'scrounged'. 'My mother scrounged it. She helped the morris a lot. Went round the big houses - Bliss's, Colville's. You couldn't buy white trousers that time of day. Well, cricket whites, but they weren't no good. People would say, "I've got a pair of white trousers, do you want them?" Bowler hats ... You never refused.'

The kit he first danced in was 'scrounged'. 'My mother scrounged it. She helped the morris a lot. Went round the big houses - Bliss's, Colville's. You couldn't buy white trousers that time of day. Well, cricket whites, but they weren't no good. People would say, "I've got a pair of white trousers, do you want them?" Bowler hats ... You never refused.' 10 His mother told me, "You'd try and find someone who had played tennis or something." Another possible venue was jumble sales. Reg 'Scudgel' Tanner, who had danced in the immediate post First War period but had since retired, gave Francis his old bell pads.

10 His mother told me, "You'd try and find someone who had played tennis or something." Another possible venue was jumble sales. Reg 'Scudgel' Tanner, who had danced in the immediate post First War period but had since retired, gave Francis his old bell pads. 8

8

As to pre-Whitsuntide practices, 'About a month before they'd start - perhaps once a week. They never used to bother much in them days. They all knew it ... We never used to practise much until we went to the Albert Hall the first time (i.e. in 1967) ... You could always tell me - I was always on the wrong foot. Well, Jinky couldn't see to correct you.' 10 Then, as now, the tradition was well able to accommodate stylistic divergences.

10 Then, as now, the tradition was well able to accommodate stylistic divergences.

He never remembers any aggravation between the two teams during the 1930s. 'I think we just used to pass each other in the street, like we do today.' The crowds weren't so big as they are nowadays, but 'they always came. There always seemed to be plenty of people around, anyway.' Unlike today, they never used to arrange specific times to dance at the big houses. 'You used to meet at eight thirty or whatever time it was to start dancing and you wouldn't know which house you were going to at what time. People stayed at home at Whitsun then. Well, the transport wasn't what it is now; and they were a part of the village. Jinky just used to play a bit of a tune as we walked up to the house and they would be waiting ... The vicar would find you about four or five o'clock and say, "Would you like to have tea at the Vicarage?" Of course, you had to give them time to get the table ready.' 10

10

There certainly was nothing like the extensive social scene that nowadays exists at Whitsun. Sometimes Jinky Wells, Headington Quarry concertina player William Kimber, and Ken Loveless, a revivalist dancer and concertina pupil of Kimber's, 'would sit in the Talbot Whit Saturday night and play for themselves, and people used to love to hear them play.' 10

10  On a similar tack, other than Whit Monday, Francis only remembers dancing at one fete in Stokenchurch during his first five years of involvement.

On a similar tack, other than Whit Monday, Francis only remembers dancing at one fete in Stokenchurch during his first five years of involvement. 4 This seemed like a far distant place at the time, and he recalls how the 'older men went into the pub for the drink and brought us out a lemonade or something - we weren't old enough to drink - while we sat on the wall and chatted up the girls. We thought it was great, wearing morris dancing clothes.'

4 This seemed like a far distant place at the time, and he recalls how the 'older men went into the pub for the drink and brought us out a lemonade or something - we weren't old enough to drink - while we sat on the wall and chatted up the girls. We thought it was great, wearing morris dancing clothes.' 9

9

One incidental anecdote told to me by Ruth Wheeler, Francis's sister, reveals something of village politics. During the 1930s the Shergold family lived next door to the Buckinghams and were good friends with one another. On Whit Monday the kids from both families would go out collecting with their floral garlands in the morning, then, because Francis danced for Jinky, and the Buckinghams for the rival team, "we didn't talk to each other for the rest of the day." 6

6

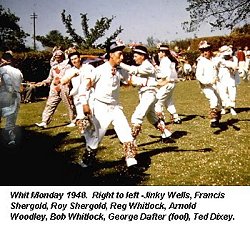

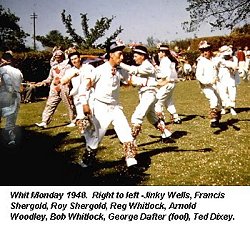

When the war started Francis enlisted in the army but, even so, almost always managed to get home for Whitsun. 'Well, our company commander was Early of Witney, one of the blanket people, so he knew what Whitsun meant to me. Even when we went to France I managed to get back. I think I only missed one year during the war.' He fought in Europe: 'Only France and Germany. I was wounded twice, but I never brought it back to Blighty.' Wells kept the team going by using men who either worked on the land or were too young to join up. 10 Local children continued to watch the practices outside the Malt Shovel. Roy Shergold told me, "You knew the dances before you started." One year, probably 1940, Roy stood in for one of the dancers at the Whit Sunday practice, and Jinky told him that he would have to dance in the team the following day. "I thought that was great."

10 Local children continued to watch the practices outside the Malt Shovel. Roy Shergold told me, "You knew the dances before you started." One year, probably 1940, Roy stood in for one of the dancers at the Whit Sunday practice, and Jinky told him that he would have to dance in the team the following day. "I thought that was great." 3

3

Some time after the war it was agreed that Francis would be the leader (Squire) and Arnold Woodley would teach the dances. In 1950 George Hunt and another newcomer (whose name is no longer recalled) joined the team. At the practice behind the Lamb on Whit Sunday Arnold said to Francis that these two were not good enough to go out the following day. Arnold said, "What if someone should ask who had taught them?" Francis replied, "What's the problem, Arnold? Tell them I did." Arnold felt so strongly over the quality of the newcomers' dancing that he wouldn't turn out on the Monday. 5 By the following year he had raised his own team, consisting mainly of young boys, so that throughout the 1950s there were again two sides touring the town at Whitsun.

5 By the following year he had raised his own team, consisting mainly of young boys, so that throughout the 1950s there were again two sides touring the town at Whitsun.

During that decade of post-war prosperity there was a great deal of apathy in Bampton concerning the morris. But although they sometimes did bookings at fetes and similar venues with only five dancers, Francis could always raise a full set of men for Whit Monday.  That is, until 1959.

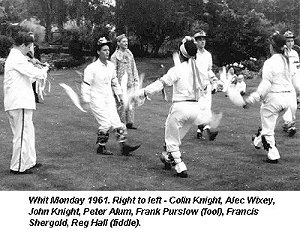

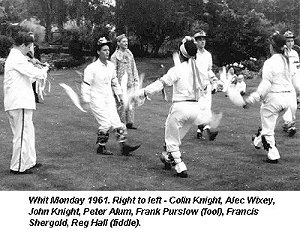

That is, until 1959. 4 Regular dancer Peter Alum came to see him some time before Whitsun to say that Arnold Woodley would, as usual, be taking a team out. Francis commented that as long as someone was going out he wasn't worried. Then, just before the day, Peter came round to say that Arnold was not going out after all. Francis, determined not to allow the dancing to lapse, quickly organised a scratch team consisting of himself and Roy, Peter Alum and John Knight. Revivalist dancer Russell Wortley from Cambridge acted as fool, and Jack Newton from Aylesbury played fiddle. Newton couldn't always remember how the tunes went, so had to consult a notebook he carried in which they were written down. 'It was the best dancing we've done. You can't go wrong with only four. I don't know if it was apathy or what. I went round and people said, "I'll see you," but never did.'

4 Regular dancer Peter Alum came to see him some time before Whitsun to say that Arnold Woodley would, as usual, be taking a team out. Francis commented that as long as someone was going out he wasn't worried. Then, just before the day, Peter came round to say that Arnold was not going out after all. Francis, determined not to allow the dancing to lapse, quickly organised a scratch team consisting of himself and Roy, Peter Alum and John Knight. Revivalist dancer Russell Wortley from Cambridge acted as fool, and Jack Newton from Aylesbury played fiddle. Newton couldn't always remember how the tunes went, so had to consult a notebook he carried in which they were written down. 'It was the best dancing we've done. You can't go wrong with only four. I don't know if it was apathy or what. I went round and people said, "I'll see you," but never did.' 1

1

In 1980 Francis was able to comment that during the recent past - even as recently as five or six years previously - 'I used to feel embarrassed to walk down the street in Bampton dressed in whites. I don't know if there was a lot of new people came into the village and they didn't know what the morris was all about or what. If there were three or four of you that was all right, but if I was on my own I felt really embarrassed. Nowadays people will stop you and say, "Where are you going today?"  There seems to be a lot more interest in the village.' Eighteen years on and that comment still holds true.

There seems to be a lot more interest in the village.' Eighteen years on and that comment still holds true.

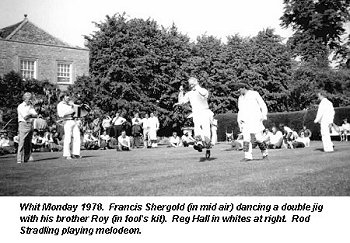

While concentrating on his substantial achievements in the morris dance field, we must not overlook Francis' many other talents. Like many Bampton children before and since, he, brother Roy and sister Ruth perambulated the town on Whit Monday with their floral garlands. 4 For half a century, beginning at age fourteen, he was one of the bellringers in the church tower. Until recent years he acted on occasion as a caller for barn dances.

4 For half a century, beginning at age fourteen, he was one of the bellringers in the church tower. Until recent years he acted on occasion as a caller for barn dances.  I recall being at several back in the early 1980s, and how his instructions were always clear and concise, and the choice of dances perfect for the competence level of his audiences. He is also a good singer in the southern English country style, and currently appears at various venues in a quartet with his nephew Jamie Wheeler (one of the regular musicians for the morris) on melodeon, and dancers John Grout on fiddle and cello

I recall being at several back in the early 1980s, and how his instructions were always clear and concise, and the choice of dances perfect for the competence level of his audiences. He is also a good singer in the southern English country style, and currently appears at various venues in a quartet with his nephew Jamie Wheeler (one of the regular musicians for the morris) on melodeon, and dancers John Grout on fiddle and cello  and Martin Landray on banjo. Francis also plays both mouth organ and melodeon, again in the no-nonsense, straight-ahead traditional southern style, and over the years he has played for the morris on those occasions when their regular musicians were unavailable.

and Martin Landray on banjo. Francis also plays both mouth organ and melodeon, again in the no-nonsense, straight-ahead traditional southern style, and over the years he has played for the morris on those occasions when their regular musicians were unavailable. 7 and

7 and  14

14

In fact, 'no-nonsense' and 'straight-ahead' are perfect terms with which to describe Francis Shergold, a man whose life has been intimately bound up in multiple aspects of the folk tradition. Although he dances very little these days, he is still often to be seen out in whites with his dancers, as he has been for over six decades.

Keith Chandler

Article MT013

Sources:

A - Interviews:

1 - Interview with Francis Shergold, 11 January 1980

2 - Interview with Roy Shergold, 2 February 1980

3 - Interview with Roy Shergold, 8 March 1980

4 - Interview with Francis Shergold, 9 March 1980

5 - Interview with Francis Shergold, 25 April 1980

6 - Interview with Ruth Wheeler, 23 May 1980

7 - Interview with Francis Shergold, 27 June 1980

8 - Interview with Louise Shergold, 1 October 1980

9 - Interview with Francis Shergold, 23 November 1980

10 - Interview with Francis Shergold, 16 December 1980

B - Other of my relevant works:

11 - Morris Dancing at Bampton Until 1914 (Minster Lovell: author, 1983)

12 - 'The Archival Morris Photographs - 4: 'The Old 'uns and the Young 'uns', Bampton, Oxfordshire, 1927', English Dance and Song 47, number 3 (Autumn/Winter 1985), pp. 26-28

13 - Bampton Morris Dancers 1915-1945: The Newspaper Accounts (Eynsham:

Chandler Publications, 1986)

14 - Review of commercial cassette, Francis Shergold, Reg Hall and Jamie Wheeler, 'Greeny Up' (Veteran Tapes, 1988), Musical Traditions 8 (early 1990), pp. 49-50

15 - Ribbons, Bells and Squeaking Fiddles. The Social History of Morris Dancing in the English South Midlands, 1660-1900 (Enfield Lock: Hisarlik Press for the Folklore Society, 1992)

16 - The Social History of Morris Dancing in the English South Midlands, 1660-1900. A Chronological Gazetteer (Enfield Lock: Hisarlik Press for the Folklore Society, 1992)

17 - '150 Years of Fiddle Players and Morris Dancing at Bampton,

Oxfordshire', Musical Traditions 10 (Spring 1992), pp. 18-24

All sound clips are from the Veteran Tapes cassette Greeny Up (VT111) - see Links.

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 24.10.02

Perhaps the best-known morris dance side of the English South Midlands is that belonging to the small town of Bampton, on the western side of Oxfordshire. While some participants and outsiders have claimed a performance history of up to six hundred years, we can more realistically confirm activity spanning a quarter of that period.

Perhaps the best-known morris dance side of the English South Midlands is that belonging to the small town of Bampton, on the western side of Oxfordshire. While some participants and outsiders have claimed a performance history of up to six hundred years, we can more realistically confirm activity spanning a quarter of that period.

During the 1930s there certainly were Whit Mondays when a second team made an appearance, but it was that led by fiddler William Nathan 'Jinky' Wells (1868-1953) who annually kept the tradition going without fail.

During the 1930s there certainly were Whit Mondays when a second team made an appearance, but it was that led by fiddler William Nathan 'Jinky' Wells (1868-1953) who annually kept the tradition going without fail.

The kit he first danced in was 'scrounged'. 'My mother scrounged it. She helped the morris a lot. Went round the big houses - Bliss's, Colville's. You couldn't buy white trousers that time of day. Well, cricket whites, but they weren't no good. People would say, "I've got a pair of white trousers, do you want them?" Bowler hats ... You never refused.'

The kit he first danced in was 'scrounged'. 'My mother scrounged it. She helped the morris a lot. Went round the big houses - Bliss's, Colville's. You couldn't buy white trousers that time of day. Well, cricket whites, but they weren't no good. People would say, "I've got a pair of white trousers, do you want them?" Bowler hats ... You never refused.' On a similar tack, other than Whit Monday, Francis only remembers dancing at one fete in Stokenchurch during his first five years of involvement.

On a similar tack, other than Whit Monday, Francis only remembers dancing at one fete in Stokenchurch during his first five years of involvement. That is, until 1959.

That is, until 1959. There seems to be a lot more interest in the village.' Eighteen years on and that comment still holds true.

There seems to be a lot more interest in the village.' Eighteen years on and that comment still holds true.