The first Scott Skinner tune I heard was The Laird Of Drumblair, the marvellously spirited performance by fiddle player Tommy Peoples on the Bothy Band's first (1975) album. It's a classic Scots strathspey in the bright-sounding key of A with all the hallmarks of Scottish style - snap rhythms, alternating ('double tonic') phrases in A-major and B-minor and ingenious descending runs of triplets at the end. Peoples, of course, is from the north of Ireland, but as Donegal fiddler John Doherty once remarked "There is only a paper wall between Irish and Scottish music". ![]() 1 On the Bothy Band album Tommy proceeds in time-honoured fashion to convert the strathspey into a reel - a sequence subsequently recycled in a thousand pub sessions throughout the celtic music world. But what of the tune's first composition? The 'Laird' in question turns out to have been an engineering entrepreneur, William McHardy, who having made his fortune in South America returned to live in Scotland, where Skinner was a regular visitor to his house. One night as the composer lay in bed "reflecting on all the kindnesses of this friend", the tune "flashed" into his head and, having no music manuscript paper to hand, Skinner dashed it off on a sheet of soap wrapper. "Ye're no' gaun tae send that awfy-like paper tae the Laird," protested his wife. "He'll jist licht his pipe wi' it!" Send it he did, however, and was duly rewarded the following Christmas with a letter of gratitude and accompanying cheque.

1 On the Bothy Band album Tommy proceeds in time-honoured fashion to convert the strathspey into a reel - a sequence subsequently recycled in a thousand pub sessions throughout the celtic music world. But what of the tune's first composition? The 'Laird' in question turns out to have been an engineering entrepreneur, William McHardy, who having made his fortune in South America returned to live in Scotland, where Skinner was a regular visitor to his house. One night as the composer lay in bed "reflecting on all the kindnesses of this friend", the tune "flashed" into his head and, having no music manuscript paper to hand, Skinner dashed it off on a sheet of soap wrapper. "Ye're no' gaun tae send that awfy-like paper tae the Laird," protested his wife. "He'll jist licht his pipe wi' it!" Send it he did, however, and was duly rewarded the following Christmas with a letter of gratitude and accompanying cheque. ![]() 2

2

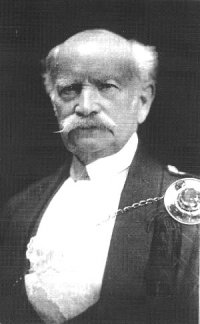

The story comes from My Life and Adventures, first serialised in The People's Journal in 1923 and re-published in 1994 by the City of Aberdeen, in association with Graham Dixon of Wallace Music, to mark the 150th anniversary of Skinner's birth. ![]() 3 Fiddlers already have reason to be grateful to Dixon for his edition of James Hill tunes, The Lads Like Beer, and it is again thanks to his efforts that Skinner's memoirs have become available in booklet form. The text runs to over a hundred pages, illustrated with the original photos and some additional press notices and concert programmes. Its release seems unlikely either to enhance or detract from the high regard in which Skinner's music is held; and this is probably just as well, since the light it throws on his character is not entirely favourable.

3 Fiddlers already have reason to be grateful to Dixon for his edition of James Hill tunes, The Lads Like Beer, and it is again thanks to his efforts that Skinner's memoirs have become available in booklet form. The text runs to over a hundred pages, illustrated with the original photos and some additional press notices and concert programmes. Its release seems unlikely either to enhance or detract from the high regard in which Skinner's music is held; and this is probably just as well, since the light it throws on his character is not entirely favourable.

Skinner cannot have been an easy man to like. Certainly he could be very pompous. Struggling for much of his life to make a half-decent living, his sense of his own value seems to have been so precarious as to require almost continuous assertion. The Life, it is true, was 'ghost-written' (by whom?), but his self-importance is more than a matter of prose style. "I have no intention," he says, "of wearying my readers with the details of my life's output of original music, which, frankly speaking, has been colossal". You feel he is shadow-boxing with some invisible adversary determined to deny his achievement, quoting, for instance, the opinion of Monti, "an Italian expert" (he of the Csardas?): "Monti was a great admirer of my work. On one occasion ... he picked up a couple of books and remarked, "Here's Bach and here's Scott Skinner. Personally I prefer Scott Skinner".

Skinner cannot have been an easy man to like. Certainly he could be very pompous. Struggling for much of his life to make a half-decent living, his sense of his own value seems to have been so precarious as to require almost continuous assertion. The Life, it is true, was 'ghost-written' (by whom?), but his self-importance is more than a matter of prose style. "I have no intention," he says, "of wearying my readers with the details of my life's output of original music, which, frankly speaking, has been colossal". You feel he is shadow-boxing with some invisible adversary determined to deny his achievement, quoting, for instance, the opinion of Monti, "an Italian expert" (he of the Csardas?): "Monti was a great admirer of my work. On one occasion ... he picked up a couple of books and remarked, "Here's Bach and here's Scott Skinner. Personally I prefer Scott Skinner". ![]() 4 I am reminded of my old copy of the Bayley & Ferguson edition of Skinner's The Scottish Violinist, its pink cover famously emblazoned with the motto: 'Talent does what it can, Genius does what it must'.

4 I am reminded of my old copy of the Bayley & Ferguson edition of Skinner's The Scottish Violinist, its pink cover famously emblazoned with the motto: 'Talent does what it can, Genius does what it must'.

His compulsive self-promotion can be wearying, but Skinner's account of a harsh and deprived childhood provides clues as to its origin. His father died when he was a baby and his mother's re-marriage was not happy. She had "a rigid belief in the scriptural adage that who spareth the rod spoileth the child", and beatings, from his mother and his school-master, "a regular martinet", seem to have been frequent. His brother Sandy, who began teaching him fiddle and cello when he was six, was also "the most rigorous of taskmasters", and meted out "humiliating punishment" whenever the child was slow. Skinner's mention of all this abuse suggests it was not just the child-rearing norm of a more punitive age and, though he says nothing himself, one can guess at a core of self-contempt beneath his later bravado.

Musically he was highly precocious. By the age of eight he was playing cello with Peter Milne, a well-known Deeside fiddle composer and - I think, significantly - "practically a father to me". (Milne was clearly not an ideal father figure. He was, for example, an opium addict - which may explain a curious remark of his: "I'm that fond o' my fiddle, I could sit in the inside o't, an' look oot.") "It was nothing unusual for Peter and me to trudge eight or ten weary miles on a slushy wet night in order to fulfill a barn engagement". And he describes a typical dance of the 1850s, held in a building with an earthen floor, lit by tallow dips mounted on wall brackets and the 'orchestra' consisting of fiddle, cello and flute. Once, returning home at five in the morning, "dragging, rather than carrying, my bass fiddle", he fell asleep against the door, too exhausted even to lift the latch, and was found there two hours later by his mother.

At twelve Skinner joined a juvenile orchestra, Dr Mark's Little Men, travelling throughout Scotland, England, Ireland and Wales. He learned to read music and his studies with Halle orchestra violinist Charles Rougier greatly extended and refined the left-hand playing technique he had acquired as a strathspey fiddler. In 1858 the Little Men performed before Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace - some years later Skinner would teach Highland dancing to the children of her Balmoral tenants, as well as composing the air Our Highland Queen in her honour. By the time he left the troupe at the age of seventeen he was on his way to becoming the formidable violinist who - both through his compositions and his discovery of a way to present traditional dance music in concert performance - was to make such an impact on Scots fiddling.

He now studied under a dancing master, William Scott, and thereafter adopted 'Scott' as his own middle name. While dancing, as much as fiddle playing, would be his livelihood for years to come, was it really in homage to his instructor that he changed his name? I think he both wished to appropriate Scott, "a great scholar, highly cultured, and handsome into the bargain", as another father; and that he was already attempting to construct for himself an identity that would be peculiarly Scottish and patriotic. It was also the name, after all, of Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), himself one of the great architects of Highland romanticism and still at that time a massively influential figure throughout Europe. Whatever his intentions, it was as James Scott Skinner that - after a brief interlude as a blackface minstrel under the name of 'Mr Grace Egerton' - he began his career, publishing, in 1865 and 1868, first Twelve, and then Thirty New Strathspeys and Reels.

By 1868, aged twenty five, he was working as a dance teacher to the tenantry at the palace of Balmoral. He established, with both dance and violin teaching, a practice apparently successful enough to allow him, around 1870, to marry fellow-dancer Jane Stuart, with whom he had a daughter, Jeanie, and in the early 1880s a son, Manson. He also worked hard as a performer, playing pieces by Rode, Paganini and Mozart, as much as traditional, or his own, music. A dozen years of this, he tells us, and "I had the patronage of all the big private families in Ross-shire, Inverness-shire, Elginshire and Banffshire. I was making about £750 a year, and was able to drive to and from the residences of my pupils in my own private trap, drawn by a beautiful pony. This equipment cost me about £150". His curiously specific boast may be a defence against his sense of being patronised in the more negative sense of the term. He describes having to divert a violin student who disdainfully announced "I'm tired of fiddling. Tell me a story". Even in retrospect, however, Skinner seems more flattered to have been associated with the aristocratic client than willing to acknowledge the insult and, still locked in the role of entertainer, repeats the story - quite a funny one, incidentally - for his readers. ![]() 5

5

As David Johnson remarks in Scottish Fiddle Music in the Eighteenth Century, "Skinner's career was out of step with his era ... Trained European musicians living in Scotland despised Scots fiddling, almost to a man". Whereas the fiddle composers of the previous century had been respected as contributors to a European mainstream, equally at ease writing minuets and sonatas or using traditional Scottish forms, the Romantics had come to prefer the view of fiddle music as the product of an untutored, preferably wild, preferably Highland, peasantry. And if folk music was primitive, almost a force of nature, what real respect could be accorded to those who performed it? In those "big private families", Skinner's status was partly that of mascot, an oddity: "jist ane o' the Almichty's curiosities". As a concert performer of 'folk' fiddle music, who at the same time viewed it from a 'superior' classical standpoint, he was also very much out on his own. His isolation from an active musical tradition in which his work could be appreciated - and its limitations recognised - may have had its inner correspondence in his lack of, and perpetual search for, a father. As it was, a quite unrealistic estimate of his own greatness was his only buttress against a nagging sense of musical and emotional fraudulence. Beneath the confidence of early success lay the threat of imminent collapse.

Yet the collapse, when it came, was displaced sideways. Skinner's account is typically melodramatic, while disclosing almost nothing: "The crash came suddenly, and in a single day I was roofless, wifeless, and penniless". It has been assumed until recently - and no doubt this was Skinner's intention - that his wife Jane suddenly died. But historian John Hargreaves, researching Skinner's life for a play presented in 1993, discovered otherwise:

'Thanks to the staff of Elgin Libraries we now know that ... on 18 April, 1885, Jane was admitted to the Elgin Lunatic Asylum ... suffering from "excitement" caused by "pecuniary embarrassment". From time to time Skinner contributed to her maintainance, though he had difficulty in keeping up regular payments. Jane Stuart died a pauper in the asylum on 5 January, 1899.'While it is possible that Skinner felt it inappropriate to make such a disclosure in his memoirs, his evasiveness seems rather to betray some sense of guilt. His habitual unwillingness to acknowledge personal or emotional troubles may even, for all we know, have contributed to his wife's breakdown. He tells us that he moved to Aberdeen and "lay quiescent for a bit" until his "innate optimism reasserted itself" and he even permits himself a little joke: "It was in the Waverley Hotel I found temporary asylum (appropriate word, for I did think I was going mad!), and there I managed to maintain myself..." Jane's hospitalisation was followed by the death of Skinner's brother Sandy, whose widow, 'Madame de Lenglee', now not only joined Skinner as a dance teacher but helped bring up his children.6

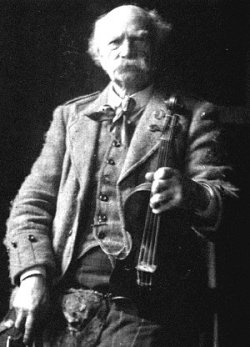

His personal life, not to put too fine a point on it, was largely a mess and clearly it was into his work that he put his energy. As a performer he now deliberately constructed himself as an icon of Scottishness. Returning from a tour of America in 1893, he tells us, "I made up my mind on two points. Firstly, I decided to have done with dancing. As a solo violinist I meant to stand or fall. Secondly, I decided to make the kilt my performance dress". He became in the mind of his public - and probably in his own mind, too - the 'Strathspey King', the very embodiment of the romantic Victorian version of traditional Highland culture. That this 'traditional', supposedly ancient, Highland culture, was in fact largely a retrospective invention of the later 18th and early 19th centuries, is persuasively, if provocatively, argued by Hugh Trevor Roper in Eric Hobsbawm's The Invention of Tradition. ![]() 7 The kilt itself, for example, was invented about 1730 by Thomas Rawlinson, a Quaker industrialist from Lancashire.

7 The kilt itself, for example, was invented about 1730 by Thomas Rawlinson, a Quaker industrialist from Lancashire. ![]() 8 While opportunism no doubt played some part in Skinner's adoption of the trappings of this Anglo-Scottish version of the Highland tradition, I think the fantasy component of Balmoralism was part of its appeal to a man seeking refuge from his own emotional reality.

8 While opportunism no doubt played some part in Skinner's adoption of the trappings of this Anglo-Scottish version of the Highland tradition, I think the fantasy component of Balmoralism was part of its appeal to a man seeking refuge from his own emotional reality.

Yet illusions can be very sustaining and Skinner's output as a composer was indeed 'colossal'. His first publications were followed by The Miller O'Hirn Collection (1881), The Beauties of the Ballroom (1882), The Elgin Collection (1884), The Logie Collection (1888) and The Scottish Violinist (1900). What Alastair Hardie has called his magnum opus, The Harp & Claymore Collection was published in 1904. ![]() 9 He made some cylinder recordings in 1905 and 1910 and recorded again in 1922. Prompted by Harry Lauder, he appeared in 1911 at the London Palladium as one of The Caledonian Four and continued touring in various 'concert parties' into his early eighties, playing at the Royal Albert Hall, for example, in 1925. His very real fame as a musician was, however, bought at the cost of a stable personal life. Apart from a period of about ten years with his second wife, Gertrude Park - from the late 1890's until 1909 when she left him to go and live in Rhodesia - Skinner resided at various hotels, or else stayed with friends, until in 1922, at the age of 79, he was able to buy a house in Aberdeen. After a final, not very successful, trip to America, he died in Aberdeen in 1927.

9 He made some cylinder recordings in 1905 and 1910 and recorded again in 1922. Prompted by Harry Lauder, he appeared in 1911 at the London Palladium as one of The Caledonian Four and continued touring in various 'concert parties' into his early eighties, playing at the Royal Albert Hall, for example, in 1925. His very real fame as a musician was, however, bought at the cost of a stable personal life. Apart from a period of about ten years with his second wife, Gertrude Park - from the late 1890's until 1909 when she left him to go and live in Rhodesia - Skinner resided at various hotels, or else stayed with friends, until in 1922, at the age of 79, he was able to buy a house in Aberdeen. After a final, not very successful, trip to America, he died in Aberdeen in 1927.

Skinner's place in the history of Scottish fiddle music is, as Graham Dixon suggests, very much a matter of debate. Skinner may have had little capacity for self-scrutiny and perhaps chose to believe his own publicity hype rather than face painful truths, but My Life And Adventures, if not a great autobiography, may explain why opinion today is so divided. Skinner emerges as a man fervently committed, possibly for the wrong reasons, to a Victorian fantasy of 'Scottishness'. Yet the music he composed (or much of it) transcended, wonderfully, the ideology by which it was inspired. Some of his great strathspeys and airs convey more emotional truth than he could ever express in his personal relations.

It is perhaps as easy for us to be put off, as it was for Skinner to be over-impressed, by nationalist ideologues like John Blackie, whose preface to The Logie Collection describes his music as being "as native to our ears and to our hearts as the purple heather is to the brae, or the graceful tresses on the birch to the glen" - this at a time when Scotland was already one of the most heavily industrialised countries in Europe. ![]() 10 Rejecting this kind of sentimentality, the whole tartan package, some on the folk scene today reject Skinner's music itself as inauthentic, his self-conscious virtuosity an aberration from the 'real' Scottish vernacular fiddle tradition. Players like Alasdair Fraser (whose opinions about Skinner, by the way, I am not presuming to guess) have set themselves - with excellent results - the project of re-creating what they take to be an earlier, more authentic Scottish style, seeking, for example, in the Gaelic-speaking communities of Cape Breton a Highlands fiddle style (and set-dancing style, too) that was all but extinguished in Scotland itself. Certainly if one's goal were to create for Scottish folk music an equivalent of the present-day Irish session scene, then the highly individualistic Skinner may seem at best an irrelevance.

10 Rejecting this kind of sentimentality, the whole tartan package, some on the folk scene today reject Skinner's music itself as inauthentic, his self-conscious virtuosity an aberration from the 'real' Scottish vernacular fiddle tradition. Players like Alasdair Fraser (whose opinions about Skinner, by the way, I am not presuming to guess) have set themselves - with excellent results - the project of re-creating what they take to be an earlier, more authentic Scottish style, seeking, for example, in the Gaelic-speaking communities of Cape Breton a Highlands fiddle style (and set-dancing style, too) that was all but extinguished in Scotland itself. Certainly if one's goal were to create for Scottish folk music an equivalent of the present-day Irish session scene, then the highly individualistic Skinner may seem at best an irrelevance.

Yet ironically, although Skinner himself was of his time in swallowing the romantic account of his predecessors as 'peasant' fiddle players - he mentions rather loftily in his Guide To Bowing, for instance, that fiddlers like Neil Gow "did good work, but would have soared even higher had they received a good sound training" - he was in reality very much in their tradition, for James Oswald (1711-1769), William Marshall (1748-1833), Niel Gow (1727-1807), Nathaniel Gow (1763-1831) and the like, always prized technical accomplishment highly. To those complaining, for instance, that some of Marshall's tunes were technically too difficult "his answer was that he did not write music for bunglers, and as all his tunes could be played, he advised them to practice more, and become better players".

Yet ironically, although Skinner himself was of his time in swallowing the romantic account of his predecessors as 'peasant' fiddle players - he mentions rather loftily in his Guide To Bowing, for instance, that fiddlers like Neil Gow "did good work, but would have soared even higher had they received a good sound training" - he was in reality very much in their tradition, for James Oswald (1711-1769), William Marshall (1748-1833), Niel Gow (1727-1807), Nathaniel Gow (1763-1831) and the like, always prized technical accomplishment highly. To those complaining, for instance, that some of Marshall's tunes were technically too difficult "his answer was that he did not write music for bunglers, and as all his tunes could be played, he advised them to practice more, and become better players". ![]() 11 John Doherty held the view, according to Alun Evans, that Scott Skinner wrote the tricky hornpipe The Mathematician "to fool the country fiddlers".

11 John Doherty held the view, according to Alun Evans, that Scott Skinner wrote the tricky hornpipe The Mathematician "to fool the country fiddlers".

The kind of concert presentation of Scots dance music that Skinner evolved - I mean his development of the 'concert reel' and the 'pastoral air' rather than the kilt-sporting and sword-dancing aspect of his performance - is kept alive today by violinists like Alastair Hardie, whose playing of Skinner tunes on his 150th anniversary tribute CD Compliments to 'The King', is, I have no doubt, much as Skinner would have liked it: a considered style on the cusp between 'folk' fiddle and 'classical' violin; Scottish music for the parlour or the concert hall. But what about Scottish music for the house dance, the ceilidh - and indeed the session? As a matter of fact, Skinner's music today is widely played both within and beyond Scotland - in Cape Breton, in New England and in Donegal, for example, albeit without the King's scrupulously annotated bowing patterns. Well known fiddlers as diverse as Jean Carignan and Bill Lamey, John Doherty, Tommy Peoples and Dave Swarbrick have all found inspiration in his music, along with countless others who play for private enjoyment.

Debate will continue and the publication of My Life And Adventures will have provided both Skinner enthusiasts and critics with plenty to reflect upon. His tunes, meanwhile - or many of them - seem assured of continuing life. "The best of them", as his friend George Riddell wrote in the Aberdeen Journal in 1927, "are robust, melodious and exceptionally well balanced", though it was the same critic's view that "It is not for the Strathspey composer to disport himself among the various keys, or indulge in fanciful chromatic progressions". In every tradition there exists a tension between the individual act of composition - and Skinner was nothing if not an individual claiming credit for original work - and the collective use and development of the music by large numbers of players. The balance between the two seems to vary between one tradition and another; in both Irish and Appalachian Old Time fiddle music the composers tend to be soon forgotten, submerged in the collective, while their Scottish and Swedish counterparts seem much more likely to be remembered by name. Skinner may have been, by temperament, belief and cultural location, at some considerable remove from his fellow fiddle players. In the end, however, it is they who will sustain his music and his reputation.

Pete Cooper - 5.8.97

Article MT007

"Do you know where you're going to, sir?" he said.

"Na." came the answer.

"Well, you're going to perdition." was the stern rejoinder.

"Eh?" exclaimed the maudlin one, waking up somewhat; "I'm in the wrang train again!"

| Top of page | Home Page | Articles | Reviews | News | Map |