Article MT063

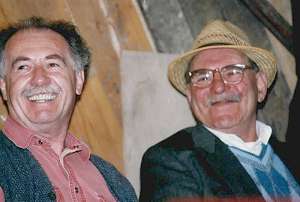

Wiggy Smith

and other members of the Smith Family

Band of Gold

[Track List] [Introduction] [Wiggy Smith] [The Songs] [Repertoire] [Credits]

Musical Traditions' fourth CD release this year: Wiggy Smith - Band of Gold (MT CD 307), is now available. See our Records page for details and/or read the glowing review. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the record, or who might find the small print hard to read, we have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here. As usual, photo credits can be seen by hovering the cursor over the picture.

All songs by Wiggy Smith, except where noted below: by Wisdom Smith, Denny Smith, Biggun (Jabez) Smith or Jean Hoskin & Tracy Butler

- The Deserter

- Where the River Shannon Flows

- I'm a Romani Rai

- My Ship Lost Her Rigging (Biggun)

- You Are the Only Good Thing that have Happened to Me

- Rich Farmer of Sheffield

- Galloway Man (Wisdom)

- Diddling/Mandi went to Puv the Grai

- Strawberry Roan

- When I was a Young Man (and Wisdom)

- Go From My Window (Wisdom)

- Dunkirk Bay

- The High-Low Well

- Robin Hood and the Pedlar (Denny)

- The Cock Flit Up in the Yew Tree

- Oakham Poachers

- Lord Bateman

- Lord Bateman (Denny)

- Riding Along in a Free Train/Mother's the Queen of my Heart

- Barb'ry Ellen

- Hobbling Off to the Workhouse Door

- The Barley Straw (Biggun)

- The Barley Straw (Denny)

- I'll Take My Dog and My Airgun Too

- Ikey Moses

- Don't Laugh at Me, 'Cos I'm a Fool

- Ship Carpenter's Mate

- The Cruel Ship's Carpenter (Denny)

- That Little Old Band of Gold

- Auntie Maggie's Homemade Remedy

- Three Jolly Butcher Boys (Biggun)

- When Schooldays are Over

- My Boyfriend Gave me an Apple (Jean & Rachel)

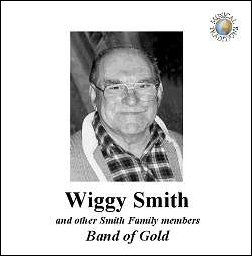

Ever since Danny, my wife, spent some time helping Gwilym Davies catalogue his tape collection I have wanted to publish a CD of his recordings of Wiggy Smith's singing. He and his father Wisdom are cult heroes among the singers in this area and, over the years, we have often heard him sing.

Unfortunately, when it came down to looking at what was available, I found that his recorded repertoire was rather smaller than I had imagined and that a number of his songs were quite short - so that a CD would have been only 45 to 50 minutes in length. Since our Musical Traditions CDs have established a reputation of presenting a full 74 minutes' worth of performance, I was not entirely happy about such a short production, and so asked Gwilym if he had recordings of any of the other singers in the family. He had, but not too many - so we decided to ask other collectors we knew who had recorded Smith Family members over the years, and were very pleased to get the co-operation of both Peter Shepheard and Mike Yates, whose recordings were from a period well before Gwilym started work.

Thus, this (now full-length) CD contains songs by Wiggy, his father Wisdom, his uncles Denny and Biggun (Jabez), and one delightful track from two of his grandchildren, Jean Johns and Rachel Butler. Although a number of the songs may be familiar to some listeners, the vast majority of these performances have never before been available. I know you will enjoy them.

Wiggy (Wisdom) Smith:

Wiggy was born on 3rd July 1926 in a covered wagon parked on the fields of Filton Common near Bristol - the area now covered by Filton aerodrome.

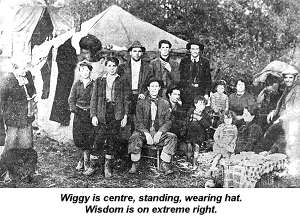

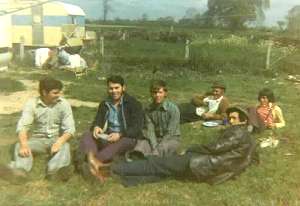

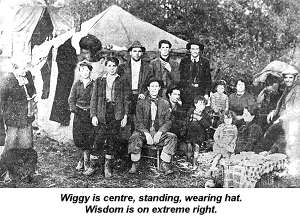

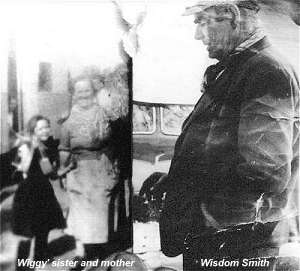

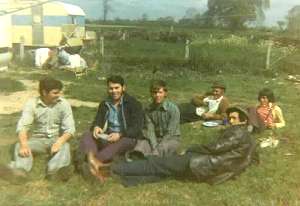

As the first boy to be born in his family, he was named after his father, Wisdom, but was nicknamed Wiggy to distinguish him from his father. In a similar manner, Wiggy's eldest son, also Wisdom, is nicknamed 'Figgy'. In his early years the family travelled, mostly around the Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and West Midland areas, sometimes living in tents, but mostly in covered wagons - the horse-drawn caravans they call 'barrel-tops'. His father was the eldest of the brothers: Jim, Jabez, Denny, Artie and Bertie. The girls were Tinia, Moselley, Georgina, Sarah Ann and Lavinia and the family as a whole stuck together, travelling in the same area for much of the time (photo below: 10 November 1950: the family camped at Coomb Hill with the 'kitchen tent' behind them - a very short distance from where Wiggy lives today). Wiggy's two brothers, Sid and Hiram, live around the Pershore area, and his youngest brother, Job, was killed in the war.

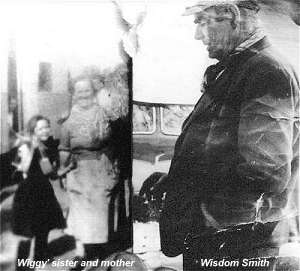

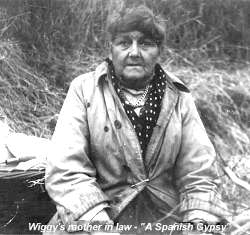

The family as a whole had originally come from the New Forest area, which may go towards accounting for the difference in accent between Wiggy and his father and uncles.  Early in the century, many fairs had 'boxing booths' which would offer a cash prize if a challenger could knock out the professional boxer. Wisdom was a big man, with big hands - "one of his hands was a big as my two are" - and was feared at fairs throughout the West Country as someone who could always knock out the 'boxing booth' champion. He was known as the King of the Gypsies. (A thinly disguised portrait of Wisdom can be found in John Moore's romantic novel September Moon, set during the hop-picking season near the Vale of Evesham).

Early in the century, many fairs had 'boxing booths' which would offer a cash prize if a challenger could knock out the professional boxer. Wisdom was a big man, with big hands - "one of his hands was a big as my two are" - and was feared at fairs throughout the West Country as someone who could always knock out the 'boxing booth' champion. He was known as the King of the Gypsies. (A thinly disguised portrait of Wisdom can be found in John Moore's romantic novel September Moon, set during the hop-picking season near the Vale of Evesham).

Wisdom's brother Artie was also a noted exponent. "I had an uncle - my father's brother - he never swore in his life. He'd never say 'Dammit!' My God, he was up here [over 6 foot] and he could fight. And all that he'd say was 'God Bless you my son. I hope you'll live long.'"

“Once at Stow Fair, for a bet - we had a brown-and-white horse called Spot - and they had a bet up there that nobody couldn’t pick him up. And he was fourteen hands high. Me dad got in underneath him, arching his back, hands down on the floor and his two legs apart and he picked him up a couple of inches off the floor. That horse - me dad could call him - ‘Come on Spot’ - and he’d come, and me dad could give him a pint of beer and he’d drink it just like a man. I’d never seen such a thing in all my life.”

Entertainment on the campsite was often just "… a stick fire! You'd have a big stick fire, and sit in a circle round it. Someone would sing a song, and then you'd go right round the circle, everybody did something." A lot of his songs were learned like this, and mostly came from his father. “And we used to have a piece of board, about as big as that [a couple of feet square] and we used to have a mouth organ and play it, and we used to get on the piece of board and tap dance. The money wasn’t about, but it was better times all round.”

Other songs came from his uncle Artie - the non-swearing boxer. "He never drank - he'd have maybe a half of shandy or a glass of lemonade. And he sang all the old songs - in the world I should think! Now I lived with my uncle for 12 months, him and his wife; that was Artie and Liza -. that was when I came out of the Army that was. And in them days there used to be nine of us as lived in a caravan - horse-drawn caravan. And when we got to bed at night, they used to sleep on the bed up at the top - the girls underneath 'em a bit and we boys on the floor. And he used to lay there and sing all the old songs and he used to say to his wife "Now I've had my song - now it's your turn Liza, you sing." And she used to lay there and sing all the old songs. I got a few that way." One of Wiggy's uncles, Luke Smith, lived further south in Gloucestershire and used to go and sing regularly in the Nag's Head at Avening. He was a great singer. "He used to sing lots of the old songs. Beautiful they were …" and he was instantly recognisable with his "long, milk-white beard right down his chest. Everyone round there knew him."

“My earliest memories were when we used to get on a bike and ride from Cirencester to Tedbury [Tetbury] to get six penn’orth of stale bread ... and we used to have between six and twelve loaves for that. If we had a rabbit, and ‘taters that was a damn good dinner and we used to save all the stale bread up and put tuppence or thruppence away - or a penny a day and buy some raisins or currants with it and make a bread pudding with it.”

In the horse-drawn wagon, they had one bed at the bottom, with the shutters drawn. “The four boys used to lay in the bottom, or the two girls would lay in the bottom,  Mother and Father would lay at the top and the four boys on the floor. That was eight of us. They was hard times.”

Mother and Father would lay at the top and the four boys on the floor. That was eight of us. They was hard times.”

“I left home when I was thirteen and I never saw my mother and father until I was nineteen years of age. I went down to Sarah at Fordham-on-Severn [?]. I lived with her and my uncle, and I got a job on the Ministry of Food, on the Severn, and I was driving a mobile crane. We used to have our money every week. Mostly tea, butter, cheese and that they used to put on these barges that we used to fetch up. I worked on it for about twelve months - I put me age up, to get extra money, you know what I mean like - and I had a letter come to report at Hazel Place, Worcester, for my medical. And Mr Horn, the area manager over it, he got me exempted, for six months. And the next time, he couldn’t get me one [exemption], so I went to Hazel Place, Worcester, and passed my medical, passed it A1, and from there I went to Norton Barracks, Worcester, in the 7th."

Wiggy served in several capacities during the Second World War and was injured by shrapnel, having to spend some time in hospital with his eyes bandaged. “I don’t like to speak of it - too many of ‘em got killed. I went to Holland, I went to France, I went to Poland - all different places.” Wiggy’s youngest brother (Job) died fighting in the war. “He got killed in France. Twenty-seven years old he was when he got killed. Right in the prime of his life, more or less.”

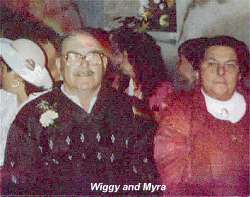

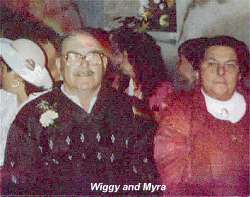

Whilst in the forces, he’d cycle from Oxford up to Leamington or Warwick to see the girl he was to marry, Myra.  He married Myra, from another Midlands travelling family and still sings You Are the Best Thing that have Happened to Me in her memory. Like her brothers, she was also a fine singer - "You should have hear Myra sing, she knew some wonderful old songs, all the poaching songs and everything." Wiggy’s fine singing meant that, with his brothers-in-law, they would visit different pubs each weekend, and Wiggy would sing with the hat being put round at the end. “[My brothers-in-law] could drink all night - I couldn’t drink. I used to do all the singing and they used to get all the drink. They used to go round with the hat - 7 or 8 bob say. That was enough to last me and my wife a couple of days for food. We had this ‘Utility Beer’ come out, during the war, a shilling a pint. And it used to give you the runs something terrible!” Later on, Wiggy performed in many of the pubs around Gloucestershire with his two brothers as The Travellers and fondly remembers the enthusiastic reception they used to receive.

He married Myra, from another Midlands travelling family and still sings You Are the Best Thing that have Happened to Me in her memory. Like her brothers, she was also a fine singer - "You should have hear Myra sing, she knew some wonderful old songs, all the poaching songs and everything." Wiggy’s fine singing meant that, with his brothers-in-law, they would visit different pubs each weekend, and Wiggy would sing with the hat being put round at the end. “[My brothers-in-law] could drink all night - I couldn’t drink. I used to do all the singing and they used to get all the drink. They used to go round with the hat - 7 or 8 bob say. That was enough to last me and my wife a couple of days for food. We had this ‘Utility Beer’ come out, during the war, a shilling a pint. And it used to give you the runs something terrible!” Later on, Wiggy performed in many of the pubs around Gloucestershire with his two brothers as The Travellers and fondly remembers the enthusiastic reception they used to receive.

However, times were hard then - "We never had the food in them days. I'll tell you the truth. It used to be a thing of porridge in the morning and you never had nothing to work on. It's all you had all day. And if you had two baked 'taters that was a week's work. And if you had a rabbit, 'taters and swedes for Christmas dinner it was the best dinner that ever you had."

“When I used to travel around Cirencester with a horse-drawn caravan, me and my wife, I knows what it is to leave my wife in bed, when the moon was up, shining, and go ferreting all night to get the rabbits. Sell them at sixpence a piece and have the skin back, and the skin was making eighteen pence, so making two bob on a rabbit, and then it came to half a crown ... We used to take them to a man we called ‘The Stuttering Butcher’ at Oaksey, out by Crudwell.  And we used to let him have the rabbits at half-a-crown a piece, and he’d give us a big breast of lamb. You know, for the wife to cook” Apart from that, their only income was from making and hawking pegs, which they sold for “two bob for two gross of pegs”. They also sold pieces of lace, or umbrellas, which they used to 'close' ready to sell.

And we used to let him have the rabbits at half-a-crown a piece, and he’d give us a big breast of lamb. You know, for the wife to cook” Apart from that, their only income was from making and hawking pegs, which they sold for “two bob for two gross of pegs”. They also sold pieces of lace, or umbrellas, which they used to 'close' ready to sell.

Wiggy worked for 20 years for Mr Berry at Elm Farm, Northwick, picking, driving and marketing as well as doing his fair share of hop picking. "When you're doing the work you eat enough for four people, especially when you had the brimstone on your hands. We used to have a great time on the last night of the hop picking, especially with the Dudleys [the people from Dudley]. That was all singing and dancing - everybody was into that, raring up! No fights or nothing. What we used to do on the last day of the picking, any of the girls picking, you’d go up behind, pick her up and - straight in the crib with her and cover her up with the hops! We used to celebrate all day and night - we used to go to different pubs. The ‘Trumpet’ on the Ledbury-Hereford road, ‘Upton Arms’ in the Balkofus [?] and a place called the ‘Fir Tree’ down by Hereford - all the pubs all round with the Dudleys. There’s still a lot of hops up that way, but they does ‘em all with machines now. It spoils the sport.”

“When we’d finished pea picking, we used to go plum picking. Then when we’d finished plum picking, we used to go hop picking - both me and Myra used to work at that. We used to pick them in what they called a crib - a big square container with a wrapper up each side. We used to pick ‘em by hand. An you used to pick 5 bushels for a shilling - and that was five ten-gallon baskets for a shilling. And then when we’d finished the hops, we used to go down around Ross-on-Wye. There used to be a man called ‘Sugarbeet’ King down there. He used to go round and get the jobs, sugarbeet pulling and mangle pulling. Topping and tailing. That’s back work! You had to tump ‘em up, the sugarbeet, you had to lay ‘em in rows first, when you pulled ‘em. Beat ‘em, then lay ‘em in rows, then go round them with a hook and knife and pick ‘em up, then you had to top ‘em, all up the row. Then when you’d finished, you had to turn round and put them all into big heaps for them to come and pick ‘em up with the tractor and trailer. That was at Ross-on-Wye and we used to do the same at Kidderminster. And we used to take the sugarbeet down into Kidderminster where there’s a sugarbeet factory there. Nowadays, they can go round with a tractor and the tractor pulls ‘em up, tops ‘em and puts ‘em in the trailer at the same time. It’s the same with blackcurrant picking - you don’t get the blackcurrant picking like you used to when you used to do it by hand.”

His previous recording session still rankled. He felt he had been given the impression that he was going to be making records, and there would be money in it. Consequently, his family expected to be treated to drink from the proceeds of Wiggy's earnings, "... but they only gev me £12, and I spent £30 on beer that night!" Added to this, he was quite indignant at being described as "a pea picker from the Vale of Evesham", feeling that this was an undignified description. For the same reason, he gets angry if he hears the song Wraggle Taggle Gypsies, feeling it to be a slur on the travellers, whose trailers are, in contrast to the description, immaculate.

Wiggy has recently been suffering badly with arthritis, and poor eyesight - he is currently awaiting an operation to remove his cataracts.  Although he isn’t as mobile as he used to be, he still loves going ferreting with his mates in season.

Although he isn’t as mobile as he used to be, he still loves going ferreting with his mates in season.

Wiggy has been on the current site, between Cheltenham and Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire for 31 years. Like many of his contemporaries, most of his travelling was done earlier in his life, and was bounded by Coventry, Warwick, Northampton, down on the fens (March) for the spud picking and back to Cheltenham area again. Although he sings several songs with Irish connections, he has never been over. "I had the chance to go to Ireland, but I've never been. A lady had a smallholding and wanted me to go over to show her how to run it, but we didn't fancy it."

Some of Wiggy's children still live in trailers, but the majority don't. Most of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren have been brought up in houses and have never travelled in the way previous generations did. Although he is well aware of just how hard the way of a life was for a traveller, he regrets that the Romany way of life is starting to disappear. "I’ve got a hundred-and- twenty-odd grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and none of the young ones - and there weren’t many of the older ones - can hardly talk Romany slang."

Paul Burgess - Summer 2000

Gwilym Davies added:

Wiggy is a very proud man. He is proud of his Traveller background, proud of his large family and proud of his musical talents. At the same time, he can be quite critical of those of whom he disapproves for whatever reason, but highly supportive of his friends. He is a man of immense charisma, whether telling an anecdote, singing a song, or teasing the barmaid, and the tough expression can melt instantaneously to one of immense joy when something strikes him as amusing. As Paul's notes show, Wiggy has lived life to the full and has seen hard times when the money has been scarce and he has had to live off his wits. Life has not been kind to him, but the fact that he has seen the hard side of life, as have most travellers, gives a special depth to his songs. At times, and in the right company, Wiggy can switch effortlessly into lacing his speech with Romany words to the point that a non-traveller cannot follow the conversation. He is acknowledged as a patriarchal figure amongst the traveller community, and a fount of knowledge of the ways of the Romany.

Notes on the recordings:

Much of my spare time in the last 30 years has been spent seeking out and recording traditional singers. When I moved to Cheltenham from Hampshire in 1972, I had already some recording experience. I soon become aware, through the singing of the Cheltenham group The Songwainers, of the existence of the Smith family of traditional singers in the town, but did not take it up at the time as other people more experienced than I, including Mike Yates, were busy making recordings of them.

My first acquaintance with Traveller singers came in 1977 when I had the good fortune to meet, befriend and record Danny Brazil, who, despite his damaged voice, had a large repertoire of old songs. Through Danny I was able to meet and record his brother Harry and his sister Lementina (Lemmy). These splendid singers have all passed on now.

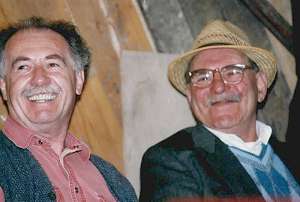

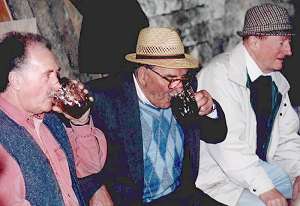

However, I did not for many years make any attempt to track down the Smith family until, in 1994, a visit from Peter Shepheard led me to Wiggy Smith in his caravan near Elmstone Hardwicke. Wiggy was at once open and honest with us and sang one or two snatches of songs that afternoon. Shortly afterwards, with the help of some singers and musicians from the Cheltenham Folk Club, I set up a lunchtime recording session in The Vic - the Victoria public house, a modest hostelry in the rather deprived St Pauls area of Cheltenham. Wiggy proved amenable to being recorded and the first song that he sang for me was his version of The Deserter.

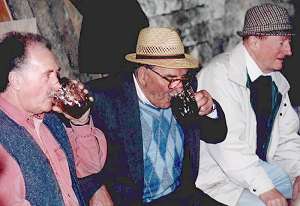

That lunchtime session proved to be the first of many, and in the ensuing months and years, Paul Burgess and I made a point of going to the Vic whenever we could, taking melodeon and fiddle with us and providing entertainment for the regulars. At all these sessions, Wiggy has obliged with a few songs and his singing usually brings a respectful hush to the bar, a tribute to the quality of his voice. Recordings in those days were made on a professional cassette recorder, but the recordings from 1996 onwards were made with a Sony DAT recorder, giving high quality digital recordings. Most of the live recordings were made in the Vic, with varying degrees of background noise. Other sessions followed in the House in the Tree, a pub frequented by the traveller community and where the music has been interlaced with step dancing and other contributions from the locals.

These recordings were supplemented with others made in the relative quiet of his caravan at a permanent site for travellers between Cheltenham and Tewkesbury, when Wiggy has been able to come up with songs from the recesses of his memory. I say relative quiet because at times I have had to contend with the barking of his little dog, Spider, who often wants to be in on the proceedings. To be welcomed into Wiggy's home is a tremendous privilege, as more than one collector or researcher has called on him only to be given short shrift in no uncertain terms. On one occasion, we were joined by another traveller, Tom Loveridge, who contributed with some songs from his repertoire, enhanced by quantities of cider laced with whisky, Wiggy's favourite drink.

On our (Paul's and my) frequent visits to Wiggy's site, we always took the occasion to look in on Danny Brazil, some 15 years older than he. Danny passed away in 1999, and Wiggy had tremendous respect for him and always referred to him as "Uncle Danny".

On some of the visits, I have let the recorder run in order to capture some of the flow of Wiggy's speech and to let him reminisce about his life.  Much of this actuality forms the basis for Paul Burgess' notes accompanying this CD.

Much of this actuality forms the basis for Paul Burgess' notes accompanying this CD.

At other times, I have been able to record Wiggy when he has been a guest at the English Country Music Weekends when they were held at Postlip, near Cheltenham. On these occasions, I have recorded Wiggy not with a tape recorder, but on camcorder. I feel that it is important to capture performances on video as well as on audio tape, and now have video recordings of much of Wiggy's repertoire. It is thus more possible to note how he approaches his singing, by gesture, hand movement, and so on. Of the recordings on this CD, three are taken from the video recordings - Lord Bateman, Ship's Carpenter's Mate and The Rich Farmer of Sheffield.

These Postlip events have been very important to Wiggy. They have been the first occasions when he has presented his songs to an entirely Gorgio (non-traveller) audience.  Although non-travellers react to songs in a different way from travellers, Wiggy has been genuinely delighted that his songs have been appreciated by the audiences. It has also been an opportunity for him to meet up with other singers such as Vic Legg, born of traveller stock himself, and with whom he struck up an immediate rapport, and Ray Driscoll, of the same age as himself and a fine singer in his own right. When Wiggy has sung on such occasions, he has automatically taken centre stage. Even on one occasion when his voice was in danger of giving up, he carried on to give compelling performances. As one member of the audience said, "It's a serious dose of reality".

Although non-travellers react to songs in a different way from travellers, Wiggy has been genuinely delighted that his songs have been appreciated by the audiences. It has also been an opportunity for him to meet up with other singers such as Vic Legg, born of traveller stock himself, and with whom he struck up an immediate rapport, and Ray Driscoll, of the same age as himself and a fine singer in his own right. When Wiggy has sung on such occasions, he has automatically taken centre stage. Even on one occasion when his voice was in danger of giving up, he carried on to give compelling performances. As one member of the audience said, "It's a serious dose of reality".

Wiggy now only allows Paul and me to record him. We are proud that he has put this trust in us, and he knows that we respect him as a person and as a performer.

Singing style:

There is no mistaking Wiggy's style as anything other than that of the Travelling people. Compared with Gorgios, the style is generally slower paced, of greater volume sung in a higher key and with the emphasis on the dramatic. Wiggy shows all these traits in his singing and savours every detail of every word he sings. As is usual with Travellers, an extra letter 'd' is slipped into many words if it improves the flow of the narrative, e.g. "He said he would give me a crownd a brace.. " (The Deserter).

A decoration much used by Travellers and by Wiggy is that of sliding up or down to a note. He uses this to great effect in his rendering of The Rich Farmer of Sheffield.

The pace of the singing is unhurried, with much use of pauses to underscore the narrative. To Wiggy, the story and the words are all-important,  even in those songs that he has in incomplete versions, such as Lord Bateman or Barb'ry Allen. The sense of the narrative is also helped by the trait of taking a breath not just at the end of the line, but in the middle of the line or sometimes in the middle of a word - something which non-travellers tend not to do. Listeners will hear many examples of this on the recordings.

even in those songs that he has in incomplete versions, such as Lord Bateman or Barb'ry Allen. The sense of the narrative is also helped by the trait of taking a breath not just at the end of the line, but in the middle of the line or sometimes in the middle of a word - something which non-travellers tend not to do. Listeners will hear many examples of this on the recordings.

The tone of the voice is important and Wiggy is much admired amongst his fellow Travellers for the fine timbre of his voice, coupled with the phrasing and the touch of vibrato at the end of each line.

Traveller singing is essentially solo singing - for listening to but not for joining in with - and Wiggy, like most, is adept at holding the listener's attention as the song unfolds. Today's singers might do well to listen to Wiggy's style, not to copy it slavishly but to learn such things as pacing a song and emphasising the dramatic.

Peter Shepheard recalled:

I first started looking for song traditions among the Cotswold Romany travelling families in January 1966 when home visiting my parents at Frocester for Christmas 1965. The first travellers I met were at Chalford, near Stroud. I then found travellers at Eastington where there was a site beside the canal, and I recorded a session in the Queen's Head in Eastington with Bob and Freda Penfow and Doris Davis. Doris suggested I should visit her father Harry Brazil at a site in Sanders Lane, Gloucester, and I did so the next day and also met Harry's brother Danny and recorded a number of songs from them both.

In April 1967 I returned home for a few weeks to recover from a hepatitis infection and spent four weeks travelling all around the countryside recording members of the Brazil family brothers Hyram, Tom, Danny, Harry, Lemmy and, later, a married sister. Harry recommended I visit a singer Maurice Smith in Stonehouse and he turned out to be a rather fine singer. Danny Brazil introduced me to a great singer Denny Smith one evening at the Tabard Bar - a cider bar in Gloucester on a corner of North Street and the Cathedral turning. It was the following year in January 1967 that Danny and I went to see Biggun (Jabez) Smith at Beachley Ferry. Through Danny's son-in-law I was taken to meet Tom (Chappie) and Mark Stephens in Bristol. I also made trips around the countryside towards Bristol and around the Forest of Dean.

Biggun Smith was recognised by the travellers in the Gloucester area as a good singer. I had earlier (in April 1966) recorded his uncle Denny Smith in Gloucester. Wiggy said of Denny “He could play a squeezebox. Cor! He played one of those and it would practically talk! He always went out for sport. His wife had thirteen lots of twins - but she never reared one ... Janey her name was, and she used to smoke black bacca. I lived with him for about 6 months - and he was all right to me. Over Bridge he used to live - opposite the Dog at Over." [now called the ‘Toby Carvery at Highnam’!]

Paul Burgess remembered:

We spent a great evening with Wiggy and his cousin ‘Biggun’ (Jabez) at the Apple Tree at Minsterworth, where Biggun was well known as a regular who would often sing. With him was Alfie Butler, who played accordion and mouth organ around the Gloucester pubs and knew several stepdance tunes, but who had given up playing on the death of his father. One of my fondest memories is of Biggun giving a riveting performance of The Barley Straw with Wiggy shouting encouragement! Biggun died suddenly, knocked down by a car as he crossed the road to ask directions at the pub near Glasshouse.

Wiggy and his father Wisdom Smith were also recorded by Mike Yates one freezing evening in a Cheltenham pub ... the Cat and Fiddle, Whaddon Road, in 1970.

Roud Numbers quoted are from the databases, The Folk Song Index and The Broadside Index, continually updated, compiled by Steve Roud. Currently containing over 200,000 records between them, they are described by him as "extensive, but not yet exhaustive". Copies are held at: The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, London; Taisce Ceoil Dúchais Éireann, Dublin; and the School of Scottish Studies, Edinburgh. They can also be purchased direct from Steve at Southwood, Maresfield Court, High Street, Maresfield, East Sussex, TN22 2EH, UK.

Child Numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child, 1882-98. Laws Numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in American Balladry from British Broadsides by G Malcolm Laws Jr, 1957.

The members of the Smith family heard in this CD, in common with many (though by no means all) Traveller singers, sometimes aspirate the start of a word beginning with a vowel, or pronounce some words unusually. Whilst attempting to transcribe the texts accurately, I have decided to omit all the former and most of the latter of these traits, for fear of rendering the printed texts risible.

Words shown in [square brackets] are either translations of dialect/cant words, or guesses/suggestions from another recording or standard text where the singer’s word is unclear or obviously wrong. Words shown in (brackets) - mainly in choruses or refrains - are alternatives at this point.

Words shown in [square brackets] are either translations of dialect/cant words, or guesses/suggestions from another recording or standard text where the singer’s word is unclear or obviously wrong. Words shown in (brackets) - mainly in choruses or refrains - are alternatives at this point.

It’s always difficult to be precise about exactly which songs are versions of what, since Travellers tend to mix the texts of their songs differently from Gorgios (non-Gypsies) - creating a kaleidoscopic picture which gives you a graphic idea of what’s happening in the story, rather than a linear narrative of the action. Sometimes this works far better than the normal approach ... other times, particularly if verses or lines have been omitted or reordered, it tends to cause confusion in an audience which is not already completely familiar with the songs - i.e. a non-traditional audience.

Lines, verses - or in some cases complete songs - shown in italics are not included on the CD. The former are omissions, added here to indicate what the singer sang at this point of the song on another occasion, and to aid the listener’s understanding of the song. The latter are fuller versions (where we have them) of very cut-down or reordered songs - again to aid the listener’s understanding. In this way we hope to put the listener more into the position of a member of a traditional audience.

1 The Deserter (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 493)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at The Victoria pub, Cheltenham, Glos, 1994)

I was once young and foolish like many who is here

I’ve been fond of night rambling and I am fond of my beer.

Sure if I had my own home and my sweet liberty

I would do no more soldiering by land or by sea.

Sure, the first time I deserted, I thought myself free

I was quick-lie followed after and brought back by speed

I was quick-lie followed after and brought back by speed

And put in the Queen’s guardroom

With heavy irons put on me.

“You take off the heavy irons and you let him go free

For he’d make a bright soldier for his queen and countery

You take off the heavy irons and you let him go free

For he’d make a brave soldier for his king and countery.”

A very popular song, with 111 instances in Roud, mostly from England - but Greig-Duncan has seven Scottish examples and P W Joyce noted an Irish one. Most of the English collections were from the southern counties, but there are a couple of examples for Yorkshire too. Its popularity does not seem to have extended into recent times, since there are only four sound recordings, with only that by Walter Pardon (Topic TSCD 514) still available.

It is sometimes titled The ‘New’ Deserter (and was printed by Such in the 1850s under that name) to distinguish it from an older ballad in which a soldier repeatedly deserts from the army until finally he is pardoned by the King and released. Wiggy Smith believes the song relates to a true event which happened during the Great War.

2 Where the River Shannon Flows (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 9579)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at The Victoria pub, Cheltenham, Glos, 1994)

There’s a pretty spot in Ireland,

Which I all-ys claimed is my land

Where the fairies and the blarney

They will never, never die.

It’s a land of old is-layly [shillelagh]

And my heart goes back there daily

Sure, there’s not a colleen sweeter

Where the River Shannon flows.

Where the River Shannon flowing

Where the three-leafed shamrock growing

And it’s ever I am going to my little Irish rose

And I’ll settle down forever and leave the old spot never

And I’ll whisper to my sweetheart

“Come on and take my heart a stór.” [Irish: my treasure; my love]

Written by James J Russell in 1905, one might guess that this is one of those north American first-generation immigrant songs of yearning for the old home-place, since all the references to its emergence in the tradition are from the US or Canada - or, all except one. John Howson recorded it from Charlie Hancy in Bungay, Suffolk, and published it on Songs Sung in Suffolk, Vol 4 (Veteran VT 104) and in his book of the same name, (1992) p.56. Charlie was a horseman and hay trader who’d "been to just about every fair in England after horses. That’s where you used to hear the old songs from the old Gypsy boys." Whether that’s where he heard this song is not recorded.

It’s a constant puzzle to me that whenever ones comes across a reference to an ’old song’, it’s usually a song like this - seldom more than 100 years old and, quite often, a good deal younger than the person referring to it as ’old’!

3 I’m a Romani Rai (I’m a Romany Gent) (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 4844)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies at the English Country Music Weekend, Postlip Tithe Barn, Glos, 27 June, 1998)

I’m a Romani Rai, I’m a poor didikai

I’m a Romani Rai, I’m a poor didikai

I live in a mansion beneath the blue sky

I live in a tent, and I don’t pay no rent

That’s the reason they call me some Romani Rai.

Now I’m roaming around the country

And this is the life that just suits me

I’m a Romani Rai, and a poor didikai

And a Romani I’ll remain.

Now I live in an old gypsy’s wagon,

With the rooftop all civvered in gold [covered]

Now I’m soon think about getting married

And having a wagon and tent of my own.

Now I’m some Romani Rai, I’m some poor didikai

I live in a mansion beneath the blue sky

And I live in a tent, and I don’t pay no rent

That’s the reason they call me a Romani Rai.

[rai - Romani for gent or lord; didikai - a person of mixed-race, Romani/Gorgio]

The word Rai (often rendered as Rye) is interesting in this context, since it’s generally not one which a Gypsy would use of himself - a Romani Mush (man or chap) would be more usual. The word is derived from the same root as Rajah and Raj, meaning Lord or its equivalent, and was first used to describe those educated men - gents - who became interested and learned in the Romani culture, and of whom George Borrow is probably the best-known example (Borrow’s first book uses this term as its title). The song was originally written for the turn-of-the-century music halls by C Bellamy and G Weeks and - unusually - has been hijacked by Travellers as a sort of an anthem. Little of the Victorian composition remains except Wiggy’s first and final stanzas - the chorus to the original.

Similar versions have been recorded from Phoebe Smith (Kent/Suffolk), Caroline Hughes (Dorset) and Waller Fuller (Sussex).

4 My Ship lost her Rigging (sung by Biggun Smith) (Roud 618)

(Recorded by Peter Shepheard in The Fisherman bar at Beachley Ferry, Gloucestershire, 3 January, 1967, during a visit with Danny Brazil)

Oh my ship lost her rigging, got blown to away,

Which it found my father a cold watery grave;

Oh sad news to dear mother, father no more,

I’m left here to wander across the wild moor.

Sure some lady of fortune, she heard me complain,

She took me and sheltered me from the cold winds and rain;

So I well did my duty, I beared her [a] good name,

My missus she died and master I came;

Sure she left me five thousand, both houses and land;

If you’re ever so poor boys you might live to be grand.

No more shall I wander and I’ll sign no employ,

And I’ll tell of misfortune till the day that I’ll die.

This is in fact a version of The Poor Smuggler’s Boy, which Walter Pardon sings on the Musical Traditions double CD Put a Bit of Powder on it, Father (MTCD305-6). A song unknown outside England, it would seem. Roud has 32 references, but only 7 other recorded singers, of whom only Angela Brazil was from outside East Anglia.

The tune is basically the same as Wiggy uses for The Deserter and which, when Biggun gets into the extended second verse, you realise is also the same one Margaret Barry uses for Londonderry on the Banks of the Foyle.

5 You Are the Only Good Thing that have Happened to Me (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 15133)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at Wiggy’s caravan, Elmstone Hardwicke, 20th July, 1995)

Are you thinking that you wasn’t meant for me

Could it be that we been all untrue

So listen, sweet heart, it just had to be.

For you are the only good thing that have happened to me.

We’ve had our ups and downs, like all lovers do

But you know in your heart that I worship you.

So don’t ever think of setting me free

For you are the only good thing that have happened to me.

This is a song that Jim Reeves first recorded in 1961, but we don’t know if anyone did it before him. (Steve Roud seems to remember a rather nice version by Skeeter Davies, but asks you not to quote him on that). Wiggy still sings this song specifically in praise of the memory of his late wife, Myra.

6 The Rich Farmer of Sheffield (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 2638, Laws L2)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies at the English Country Music Weekend, Postlip Tithe Barn, Glos, 17 June, 1995)

Oh, there was a rich farmer at Sheffield,

And to market his daughter did go

His daughter not being afraid though

She’d been on the highway-oh before.

She met with three bold-faced ... they was robbers,

Three pistols they held at her breast

“For it’s money and clothery we declare,

’r else we’ll take your sweet life in distress.”

They ripped the poor girl stark naked

And they gave her the bridle to hold

“Now it’s money and clothes we declare

Else we’ll take your sweet life in distress.”

She put her left leg in the stirrup

And she mounted her horse like a man

It’s over hedges and ditches she galloped,

“Now come catch me bold rogues if you can.”

She rode to the gates of her father,

And she shouted all over the farm

“Dear Father, I’ve been in great danger

But those rogues they hanna [haven’t] done me no harm.”

She put her grey mare in the stable,

And she spread the white sheet on the floor

She counted her money twice over

Five hundred bright pounds and some more.

He said, “Dear daughter, if you have that fortune,

On top of that I will give you more,

And if ever you live to get married,

It’ll keep the cold wind from your door.”

Sam Richards, during his collecting of songs from travellers in the West Country (and particularly Devon), came across so many versions of what he called The Highwayman Outwitted offered during ‘the first encounter or first recording session with a singer’ that he postulated the theory that ‘the singers, it seems, have picked on a song which shows how the potentially weak and powerless [themselves] are capable of looking after themselves in the face of any intrusion [the folklorist]. The content of the song, in featuring a fictional character who acts in a way that they admire and are amused by, sorts out, from the very beginning their relationship with the outsider.’ (Sam Richards: ‘Westcountry Gipsies: Key Songs and Community Identity’ in Michael Pickering & Tony Green (eds.) Everyday Culture: Popular Song and the Vernacular Milieu, Open University Press, Milton Keynes, 1987, p.125 & p.145). Gwilym and Paul did not experience this with Wiggy, who sang the song for them after they had met and recorded him quite a number of times.

This appears to be the only time (in Roud’s 52 examples) that Sheffield is mentioned in the title of this song - Chester, Leicester, Devonshire and Yorkshire are among the more popular locations; and the man is frequently a merchant, rather than a farmer. It’s a sad reflection on the way things were, that the gallant heroine of the piece is not even named and must be content to exist solely as the daughter of a bloke whose only contribution to the action is the offer of a dowry (and, in many versions, a truly stupid question ... ). Still - she does get to keep the loot.

Naked women are enduringly popular, which may account for the song still being sung by country singers until quite recently - Roud notes 14 sound recordings of which those still available are Charlie Stringer (Veteran VT 103), Harry Green (Veteran VT135), Betsy Renals (Veteran VT 119), Jon Dudley (Coppersongs CD2), Jim Copper (Folktracks FSA082), Bob Copper (Folktracks 90-239) and Alec Bloomfield (Folktracks FSA099).

7 The Galloway Man (sung by Wisdom Smith) (Roud 1737)

(Recorded by Mike Yates at the Cat and Fiddle pub, Whaddon Road, Cheltenham, in 1970)

See once on a farm they grabs ’n ol’ sow

(grunt)-ow, (fart)-ow, (whistle)-idle-y-dow

With a-lee, with a-lyre, with a-lee an’ me poor go round

We poor the bouncing Galloway man

(grunt)-an, (fart)-an, (whistle)

Over the bouncing Galloway man

See, this old pig larned the young’uns to grunt

(grunt)-unt, (fart)-unt, (whistle)-idle-y-dunt ...

See, three little pigs went into the straw ...

See three little pigs ’ad six months in gaol

One one to the t’other he don’t give a suller [bugger]

So long as they gettin’ the best o’ swill ...

Obviously a near relative to Albert Richardson’s famous 1927 hit song The Old Sow (Zonophone T5178), now available again in Topic’s Voice of the People series (Vol 7, First I’m Going to Sing You a Ditty TSCD 657). Whether this is another version, existing alongside that one in the tradition, or whether it is a subsequent development from it will probably never be known!

8 Diddling / Mandi Went to Puv the Grai (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 852)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at Wiggy’s caravan, Elmstone Hardwicke, 11th August, 1994)

He said, mandi went to puv the grai

Down by the pani side

Up jelled a mingri to lell mandi’s grais

Mandi made a put at him

Delled him on the point of the chin

And dordi, dordi, dordi, and can’t mandi kor!

[I went to put the horses to pasture, down by the riverside. Up came a policeman, to take my horses. I threw a punch at him - struck him on the point of the chin. God! and can’t I fight!]

Probably the most well-known song in the broken language of Anglo-Romani among the English Travellers. The above translation is basically Wiggy’s. Since the language exists in numerous dialects developed by sometimes extremely small groups of speakers, and because words are sometimes used incorrectly (as in jelled - ’came’ would be welled or velled), it’s almost impossible to provide an unchallengeable translation of the particular words used here. However:

mandi = I;

puv (or poov) = literally ’earth’ - thus field or pasture

grai = horse (particularly a stallion)

pani = water

jell (or jall) = to go

mingri = policeman (same root as muscro or musker)

lell = take;

put = slang/cant for punch or poke

dell = to give or strike

dordi = exclamation, something like Dearie me! Good Grief! Christ! Bugger me! or worse, depending on the speaker

kor = fight.

Versions of this song have been collected from Mary Ann Haynes, Sussex, Frank Copper, Kent, Caroline Hughes, Dorset (Saydisc CD-SDL407) and Peter Ingram, Hampshire (Topic TSCD661).

9 The Strawberry Roan (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 3239, Laws B18)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at Wiggy’s caravan, Elmstone Hardwicke, 20th July, 1995)

Oh let me tell you a tale of a good one I know

Of the bucking old bronc, the Strawberry Roan

Well the time it rode hard, not earning a dime

Being out of a job, suspending my time

When a stranger come up, and he says “I suppose

You’re a bronc-busting man - I can tell by your clothes”

“For the sake at your rank [?], there was none I couldn’t tame

But it was riding wild ponies is my middle name.”

Oh, the Strawberry Roan, oh, the Strawberry Roan,

I ride him until he lays down with a groan

There’s mary [nary] a bronco from Texas to Rome

Could ride that Strawberry Roan.

There’s no fool and now I’ll say this old pony, he can step

For I’m still sitting tight and I’m earning a rep

When my stirrups I lose, ?? on my hat

And the ?? in leather as blind as a bat

For he makes one more jump - he is headed up high

Leave me sitting on air, way up in the sky

For I turned over twice and I came back to earth

And I started to cuss him - the day of his birth.

Oh, the Strawberry Roan, below the Strawberry Roan,

That some perishing critter was even [heaving?] alone

There’s mary [nary] a bronco from Texas to Rome

Could ride that Strawberry Roan.

Although I’ve heard this sung by several Travellers, it was clearly not a song though worth recording by most British collectors, even recently - since all the rest of Roud’s 18 examples come from the USA, where it was written by Curley Fletcher in 1915 - with a full complement of fifteen verses! The only other sound recording is by Rex Kelly and appears on Paramount Old Time Tunes (John Edwards Memorial Foundation JEMF 103) - one may presume, then, that it featured in a Western movie at some point. It’s extraordinary that the basics of the story have somehow been retained in Wiggy’s two double-length verses. He learned it from the radio - hearing it performed by Big Bill Campbell and his Hillbilly Band (or Hilly Billy Boys, as Wiggy always calls them). Here’s the full original 1915 text:

The Strawberry Roan (Roud 3239, Laws B18)

I was laying round town just spending my time

Out of a job and not makin’ a dime

When up steps a feller and he says, "I suppose

That you’re a bronc rider by the looks of your clothes?"

He guesses me right. "And a good one I’ll claim

Do you happen to have any bad ones to tame?"

He says he’s got one that’s a good one to buck

And at throwing good riders he’s had lots of luck.

He says this old pony has never been rode

And the man that gets on him is bound to be throwed

I gets all excited and I ask what he pays

To ride this old pony a couple of days.

He says, "Ten dollars." I says, "I’m your man

The bronc never lived that I cannot fan

The bronc never tried nor never drew breath

That I cannot ride till he starves plumb to death."

He says, "Get your saddle. I’ll give you a chance."

We got in the buggy and went to the ranch

We waited till morning, right after chuck

I went out to see if that outlaw could buck.

Down in the corral, a-standin’ alone

Was this little old caballo, a strawberry roan

He had little pin ears that touched at the tip

And a big forty-four brand was on his left hip.

He was spavined all round and he had pidgeon toes

Little pig eyes and a big Roman nose

He was U-necked and old with a long lower jaw

You could tell at a glance he was a regular outlaw.

I buckled on my spurs, I was feeling plumb fine

I pulled down my hat and I curls up my twine

I threw the loop at him, right well I knew then

Before I had rode him I’d sure earn my ten.

I got the blind on him with a terrible fight

Cinched on the saddle and girdled it tight

Then I steps up on him and pulled down the blind

And sat there in the saddle to see him unwind.

He bowed his old neck and I’ll say he unwound

He seemed to quit living down there on the ground

He went up to the east and came down to the west

With me in the saddle, a-doing my best.

He sure was frog-walkin’, I heaved a big sigh

He only lacked wings for to be on the fly

He turned his old belly right up to the sun

For he was a sun-fishin’ sun of a gun.

He was the worst bronco I’ve seen on the range

He could turn on a nickel and leave you some change

While he was buckin’ he squalled like a shoat

I tell you that outlaw, he sure got my goat.

I tell all the people that pony could step

And I was still on him a-buildin’ a rep

He came down on all fours and turned up on his side

I don’t see how he kept from losing his hide.

I lost my stirrups, I lost my hat,

I was pullin’ at leather as blind as a bat

With a phenomenal jump he made a high dive

And set me a-winding up there through the sky.

I turned forty flips and came down to the earth

And sit there a-cussing the day of his birth

I know there’s some ponies that I cannot hide

Some of them living, they haven’t all died.

But I bet all money there’s no man alive

That can ride Old Strawberry when he makes that high dive.

10 When I Was a Young Man (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 1165)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at Wiggy’s caravan, Elmstone Hardwicke, 11th August, 1994)

Oh when I was a young man, I was in all my dreligh [delight?]

I was drinking and a-smoking, boys, from morning until night

For when I’ve spent my score, boys, how can I spend any more

For when I’ve spent my score, boys, then I’ll boldly work for more.

So I walked into the public house and I called for a pint of the best

And the landlady she looked at me, and she brought me in the slops

And that’s what caused me in my rags and she all in her silks

So good Lord how that landlady, how she did gaze on me.

Then Wisdom Smith (recorded by Mike Yates in 1970) sings:

... she goes in for the quality of the best, and she fetch me in the drops

That’s the reason why she’s in her silks and me all in my rags

My britches tore at the knee, my boys, my coat wore at the elbow

And good Lord how that landlady, how she did gaze on me.

For it was early next morning, I was walking the streets all up and down

There I saw my landlady, all in her silk gown

“Do I owe you any money, your bacca, beer or ale?

For if I do, I must’d a-been in my old ragged [tail?]”

In the Folk Music Journal, 1969, Frank Purslow wrote an article on the collector Alfred Williams; it includes the following passage:

Another fairly popular song, recorded by most collectors at the beginning of the century, was The Drunkard, of which only one incomplete version has so far appeared in the Journal noted by the late E J Moeran in Norfolk (JFSS 8, 276). Throughout the whole of the 18th and 19th centuries, drunkenness was the enduring vice of the greater part of the English labouring classes - on the part of women as well as men. Perhaps it never reached such orgiastic peaks in the countryside as it did in the towns, where a plentiful supply of cheap gin (’Geneva spirit’) and ale made it easy for the people to forget for a few moments the squalor and misery in which most of them lived. Nevertheless, the numerous anti-drink songs and tracts met with as ready a response among teetotallers and ’moderates’ in rural areas as they did in the towns. Williams noted this very good text of The Poor Drunkard from Charles Messenger, of Cerney Wick, Gloucestershire.

Mr Messenger’s seven-verse turn-of-the-century text sounds very close to what may have originally been written, with none of the ’feel’ of a song which has passed through the oral tradition. Ken Stubbs collected a version of the song from Bill ’Mousey’ Smith, a Traveller in Edenbridge, Kent in 1967, and published it in his book Life of a Man, EFDSS, 1971? Bill’s brother Frank also sang the song, as did another relative, Walter Smith, who Stubbs recorded at Horsmonden, Kent, in 1962. Yet another version was recorded from Bob Small in Devon by Sam Richards, Tish Stubbs and Paul Wilson in 1974/6, and was released on People’s Stage Tapes 08 and Topic 12TS 349 Devon Tradition.

What’s more, Pete Shepheard also recorded a version on 23 April 1966 from Maurice Smith at Stonehouse, Stroud, Glos (ie. from the same geographical area as Wiggy and Wisdom). This one gives a more coherent account of events, so I’ve decided to include it here.

When I Was A Young Man (as sung by Maurice Smith) (Roud 1165)

When I was a young man I took great delight,

In drinking and a-smoking from mornin’ to night;

It’s a-drinking and a-smoking till I spent all my store,

And when I have spent all boys how can I spend more?

Now as I was a-walking the streets up and down,

There I saw my landlady dressed in her silk gown;

With me coat tore at the elbows, my britches at the knee,

Good Lord, how that landlady she gazed upon me.

No longer could I bear it, straight up to her I went,

“Do I owe you any money or what is your intent?

Do I owe you any money for tobacco or beer?

For if I did you must have been in your old ragged gear.

“Now be off then you drunkard, be off then”, cried she,

“For I very well do know what you drunkards all do be;

When you call for the best of ale and I bring you the dregs,

That’s why I’m in my silk gown and you’re in your rags.”

11 Go From the Window, My Love, Go (sung by Wisdom Smith) (Roud 966)

(Recorded by Mike Yates in The Cat and Fiddle, Whaddon Road, Cheltenham, 1970)

You go from the window, my love, go.

The Devil’s in the rest an’ we cannot understand

Please go from the window, my love, go.

For the cuckoo’s in the nest an’ we cannot take no rest

Go from the window, my love, go.

For the Devil’s in the man an’ he cannot understand

Go from the window, my love, go.

The earliest known British version of Go from My Window is the one printed in 1587-88 by John Wolfe of London and a set of variations on the tune current in the late 16th century were composed by either John Mundy or Thomas Morley and included in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book. Another well-known version appears in Act III of Beaumont and Fletcher’s play The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1613).

Roud has 16 references to this song, including five sound recordings - but it has been extraordinarily widespread. Jeannie Robertson in Aberdeen knew it, so did Anne O’Neill in Belfast, a Mrs Hall in Stannington, Northumberland and John Woodrich in Thrushelton, Devon. It’s even included in Negro Folk Rhymes (expanded edn, 1991), Talley, pp.75-76.

After Wisdom finished singing he leant across the microphone and said [to Mike Yates], ”You understand, don’t you, that it was a Gypsy woman singing that song. She sang it in her trailer. Her husband was out poaching, you see, and a policeman was waiting to catch him in the trailer when he returned. Now the woman heard her husband coming, so she warned him not to come in. She took her baby in her arms, because it wasn’t sleeping, and sang that song. The policeman thought that she was singing the baby to sleep, but she wasn’t, she was warning her husband not to come into the trailer. That’s true , that is.”

12 Dunkirk Bay (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 5350)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at Wiggy’s caravan, Elmstone Hardwicke, 18th November, 1999)

It’s an old Australian homestead, with the ivy round the door

A girl received a letter, from her boy who’s in the war

With her mother’s love and kisses, she give way to tears and sighs

But as she wrote this letter, sure, the tears fell from her eyes.

Why should I weep, why should I pray?

My love’s asleep, so far away,

But (And) he played his part that Autumn day

And left my heart on Dunkirk Bay.

Sure, she joined a band of nurses, underneath the cross of red

She swore to do her duty, for her loved one who were dead

Many boys they came to woo her, and she turned them all away

And this was her sad story, to the brave on Dunkirk Bay.

Why should I weep, why should I pray ...

This song - or at least the more usual Suvla Bay version - seems to have caught on with older singers in the fairly recent past, since I never remember hearing it back in the late-1960s, yet it’s rare to get through an evening without it, these days. But perhaps I move in different circles now.

The eight instances noted in Roud cover the counties of Dorset, Gloucestershire, Hampshire, Suffolk and Sussex, and recordings have been published of Gordon Hall (Veteran VT 121), Jack Tarling (Neil Lanham Tapes NL01), George Hirst (Old House OHC108), and Bob Hart’s old pal Clarence (Neil Lanham CD NLCD3).

13 The High-Low Well (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 1697)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at Wiggy’s caravan, Elmstone Hardwicke, 13th April, 1995)

For as we hollered out, as we fell out,

As we hollered out so wide

Sweet Jesus he turned-ed hisself short round

Neither to laugh nor to smile

And the water did fall from sweet Jesus’s eyes

Like the water from the sky.

“Dear mother, I have been to a merry little town

As far as the high-low well

And there I did saw some the findest children in [finest]

That ever any tongue could tell.

I axed them children could I play ’long with them

And they say ‘Yes, quite well’,

So we were nothing else but a mild Mary’s child

Born down in an ox-filled stall.

If we were nothing else but a mild Mary’s child,

Born down in an ox-filled stall

Then you shall be the king and the crown of heaven

And the ruler above we all.”

“When I first sung that song, I was seven years of age, and I sang it at a placed called Ducklington. That’s in Oxfordshire, Witney. What we used to do there, when we had a horse-drawn caravan, we used to pay sixpence a night there, in a place called Ducklington Lane - that was for the horse-drawn caravan and the horse. That was - I was seven years of age then - and the lady’s name, what owned it, was Mrs Stafford. And we used to go up - and we used to have those old paraffin heaters in them days - and you could have a gallon of paraffin then, for three’apence ... and a packet of Woodbines was tuppence’apenny, for ten Woodbines. And your cider - if you had draught cider in a pub - it was like thruppence a pint.

I sung it in a place in Ducklington - I can’t remember the name of the pub now - and I think I had about one and ninepence to walk out with, and that was on the Christmas dinnertime, and my father was in the pub and he said to me, ”Buy me a pint, now ...” I said ”you’ll get nothing!” ”Buy me a pint, now, son.” he said. So I had the one and ninepence, he took the shilling and I had the ninepence, and that’s the God-almighty truth in them days.

No - I learned it from my grandfather ... his father. My grandfather was named Jabez - Jabez Smith ...”

Cecil Sharp collected six versions of this unusual song in Cornwall and one in Gloucestershire in 1919 - though whether Isabel Fletcher of Cinderford and Wiggy’s grandfather had similar examples is not known. It’s a close relation to the well-known Bitter Withy (but leaving out the drowning incident and Mary’s whipping Jesus with willow twigs afterwards), and most of the 35 known versions are titled The Holy Well. Only three other sound recordings exist: Ella Mary Leather recorded two versions on phonograph records, which Vaughan Williams later transcribed. The singers were Mr J Hancocks (70), at Monnington, in October 1908 and Mrs E Goodwin (60), at King’s Pyon, March 1909. These were published in her The Folk-Lore of Herefordshire, Jakeman & Carver, Hereford, 1912, pp.186-7.

Peter Kennedy also recorded a Mrs Charlotte Smith in Tarrington, Herefordshire, in 1952, for the BBC - she was also a Traveller, as was at least one of Sharp’s sources. Wiggy describes it as “an old Travellers’ Christmas Carol”.

14 Robin Hood & the Pedlar (sung by Denny Smith) (Roud 333, Child 132)

(Recorded by Peter Shepheard in The Tabard bar, North Street, Gloucester, 27 April, 1966)

(Italic additions from subsequent discussions with Denny and further recordings made at Walham Tump, Gloucester, 8 May 1966)

Oh its all for a pedlar and a pedlar brave

Oh some pedlar he seemed for to be

He put his pack all at his back

And away went whistling right over the lea.

Oh the first two men oh that he met

Was two quarrelsome men seemed for to be

Now there’s one of them called Bold Robin Hood

And the other callèd Little John so free.

“Now what brings you there all in your pack?” cried Little John

“Come tell to me right speedilee.”

“Oh I have three yards of the gay green cloth

And silken bowstrings by two and three.”

“Now if you have three yards of the gay green cloth

And silken bowstrings by two and three

Then by my life,” cried Little John

“Your pack and all shall go along with me.”

“Oh no, oh no,” said the pedlar bold

Oh no, oh no, that never shall be

For there’s never a man from fair Nottingham town

Shall take one half of my pack from me.”

Then the pedlar he set down his pack

He lowered it right a-past his knee

Saying, “If you can make me fly three yards from this

Then my pack and all shall go along with thee.”

Then Little John, oh, he drew his sword

And the pedlar by his pack did stand

They fought until they both did sweat

When Little John cried, “Pedlar, pray hold your hand.”

They fought until they both did sweat

Crying, “Pedlar, pedlar, you’re too good a man.”

Now Bold Robin Hood was standing by

And at the joke he laughed quite free

Saying, “There’s many a man from fair Nottingham town,

Could beat both the pedlar and also thee.”

Then Bold Robin Hood he drew his sword

And the pedlar by his pack did stand

They fought until the blood did run

When Bold Robin Hood cried, “Pedlar, pray hold your hand.”

They fought until the blood did run

Crying, “Pedlar, pedlar you’re too good a man.”

“Now what is your name?” cried Bold Robin Hood

“Come tell to me right speedilee.

“Oh no,” said the pedlar, ”That never could be

But it’s your name you will tell unto me.”

“Oh the one of us is called Bold Robin Hood

And the other’s callèd Little John so free.”

“Then by my life,” said the pedlar bold

“It’s my name I will tell unto thee.”

“Now my name is Bill Scarlet from a foreign part

An a many a long mile beyond the sea

For killing a man on my father’s land

My own native country I forced to fly.”

“Oh if your name is Bill Scarlet from a foreign part

And a many a long mile beyond the sea

Then it’s me and you is two sister’s sons

Oh what nigh first cousins, oh can we be?”

Oh they goes in the alehouse though it being close by

They cracked bottles by two by three .......

They goes in the alehouse that was close by

And they drank bottles by two by three.

(There is no fault with your CD - Denny did just stop like that on the recording!)

I had always thought that this was one of those big ballads to have remained hugely popular against all the odds - but there are only 44 versions in Roud. Except for a handful in North America and two in Scotland, they are all English - and almost all of those are from the South East. Few of the named singers appear to be Travellers which was also a surprise, since I had an idea that it was something of a favourite among them. There’s also only one other sound recording; Hamish Henderson collected it from Geordie Robertson in Aberdeen, but no date is given.

This is perhaps a reflection on the Folk Song Index’s range - Steve can only include information which is publicly available or, when not, is passed on to him for inclusion. It does come as a bit of a shock to find that details of many of the recordings I’ve had through my hands in the last couple of years have not been passed on to him for inclusion - but perhaps it’s early days yet. May I urge anyone with recordings of traditional singers to pass the basic details on to Steve at the address given at the top of this Songs section.

15 The Cock Flit Up in the Yew Tree (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 230)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at Wiggy’s caravan, Elmstone Hardwicke, 11th August, 1994)

Oh the cock flit up in the yew-tree

The hen come chittelin’ by

I wish you merry Christmas and every day a pie.

A pie, a puddeny peppercorn

The fattest pig that ever was born

So open the door and let the New Year come in.

God bless this lady of this house

Beside the master too ..........

Please leave me a little piece

For singing it so well ..........

Perhaps surprisingly, this fragment of an old Christmas song has been noted eight times: Sharp found it in Shropshire being sung by both Henry Bould and a Mrs Halfpenny in 1911, and more recently Katharine Thomson heard it from Elsie Marshall of Birmingham, and Roy Palmer collected it from Jessie Howman in Gloucester and George Dunn in Quarry Bank, Staffordshire. Wiggy’s is the only known sound recording.

16 The Oakham Poachers (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 1686)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at The Victoria pub, Cheltenham, Glos, 4th December, 1994)

It was on last Feb-uary,

Against our lord’s cont-rary

Three brothers being wet and weary

Up a-poaching they would go.

Off to Oakham woods they rambled

In among the briars and brambles

But it’s outside, up near the centre

Up into ambush they did lie.

These three brothers, being brave-hearted

They boldly kep’ on firing

Until one of them got the fateful blow

And it showed they was overthrown.

Off to Stafford jail then they was taken

And so cruelly were they beaten

For it’s in Stafford jail they does now lie

Until their trial it does come on.

Now all you jolly poachers

That does hear of we three brothers

There was our brothers’ sake makes our heart aches

And they begged the both to die ... Try that one!

Although Roud lists 25 instances of this song, it has been collected from only two singers apart from Wiggy: Robert Miller of Sutton, Norfolk (by E J Moeran, in 1922); and Goliath Cole of Oakley, Hampshire (by George B Gardiner, in 1908). It’s found in a handful of books and journals, but is most known from its appearance in around 20 broadsides or catalogues of broadsides - in the light of which, it’s surprising that The Oakham Poachers is seldom encountered today. Wiggy’s powerful version seems to be unique in placing the captured poachers in Stafford gaol.

17 Lord Bateman (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 40, Child 53)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies at the English Country Music Weekend, Postlip Tithe Barn, Glos, 27 June, 1998)

Lord Bateman was a noble lord

A noble squire of a degree

And he stepped his foot on aboard of shipping

That some foreign country he would go and see.

For he sailed north and then sailed west

Until they got to the grand Turkey

And there he was put into that prison

Until his life it did get quite weary.

Lord Bateman had a lonely daughter

That lonely daughter of high degree

And then she swore she would take him from prison

And at last Lord Bateman then she did set fee.

For there is a knock upon your doorstep

There is a lady here to see

She’s enough plain gold all around her middle

For to set young Bateman and his captain free.

18 Lord Bateman (sung by Denny Smith) (Roud 40, Child 53)

(Recorded by Pete Shepheard in The Tabard bar, North Street, Gloucester, 27 April 1966)

(Italic additions from subsequent discussions with Denny and further recordings made at Walham Tump, Gloucester, 8 May 1966)

Lord Bateman was, oh a noble lord

Some noble lord of high degree

He put his foot on aboard of shipping

Some foreign counteree, oh he would go and see

He sailèd East and he sailèd West

Until he came to proud Turkey

’Til he was locked up and put in prison

Unto his dear life, oh it was all awry.

Now in this prison there growed a tree

It growed so stout and manfully

But he was chainded all by his middle

Unto his dear life, oh it was almost gone.

Now the jailkeeper had one ondlye daughter

One ondlye daughter of high degree

She stole the keys of her father’s prison

She swore Lord Bateman, oh she would go and see

She stole the keys of her father’s prison

She swore Lord Bateman that she would set free.

Now when she gets up to Lord Bateman’s prison

But when, oh she got up to him

“What would you give to a fair young maiden

That’s out of prison that would set you free?”

“Now I have got houses, I have got land

Part of Northumblimands [Northumberland] belongs to me

I would give it all to a fair young maiden

That’s out of prison that would set me free.”

Now seven long years they made a promise

Oh seven long years they kep’ it strong

Till one day she packed up her rich gay clotherie

And unto Northumblimand she did sailèd on.

... or the following 4 verses in place of the one above:

She took him to her father’s parlour

She give him a glass of the best of wine

And every time that she raised the glass

She said, “Oh Lord Bakeman I wish you were mine.”

“Now seven long years I would make a promise

And seven long days to remember strong

If you would wed with no other woman

And it’s I would wed with no other man.”

She took him to her father’s harbour

She give him a ship of noted fame

And as he sailèd out o’er the ocean

She said, “Oh Lord Bateman I’ll ne’er see you again.”

Now seven long year it being gone and past

And seven long days to remember strong

Till one day she packed up her rich gay clotherie

And unto Northumblimand she did sailèd on.

Now she sailèd North, she sailèd West

Until she come all to Turkey

There she saw was the finest castle

That ever her two eyes did set upon.

But when she got to Lord Bateman’s castle

She boldlye ringèd all at the bell

There was none so ready but that young proud porter

To answer that gay lady at the door.

“Now is this, oh Lord Bateman’s castle?

Or is it it’s here his noble Lord?”

(or is his noble Lord within?)

“Oh yes gay lady, he’s just returnin’

For he’s just retaken of his new bride in.”

“Now you tell him to send me a slice of his best of bread(??)

Likewise a glass of his best wine

In remembranct of, oh a fair young maiden

That’s ’leased him from prison whilst he was close confine.”

Now away, oh away went this young proud porter

And away, oh away, oh then went he

But when he got to Lord Bateman’s parlour

But he fell upon his bended knee.

“Come rise, come rise, my young proud porter

Come rise, come rise, and tell to me.”

“That the finest, gayest, ever saw young lady

She’s at your door, oh a-standing by.

She have got rings on every finger

She have got most like every three

(On some of them she have got three)

She’s more plain gold hangin’ round her middle

That would buy some of this half wild counteree.”

“And she asks you to send her a slice of bread

Likewise a glass of your best of wine

In remembranct of oh a fair young maiden

That leased him from prison whilst he was close confine.”

Oh jugs and bottles he did kick down

Tables, swords, he made them fly

“I’d rather have it [her?] nor ten hundred guineas

My proud young Susan she’s across the sea.”

Oh the bells did a-ring and the bands did a-play

Lord Bateman married two brides one day.

This old ballad is the second most popular song I’ve encountered while surfing the Roud databases - with 480 entries. Its earliest publication is shown as 1792 when it appeared in Buchan’s Scottish Ballad Book pp.29-33, from the singing of Mrs Anna Brown, who called it Young Bekie (the alternative, perhaps older? title of the ballad is Young Beichan). Since that time it has been popular right across the English-speaking world and has been recorded on around 30 occasions, the earliest being Percy Granger’s of Joseph Taylor (1908), the most recent, possibly, being this one of Wiggy in June 1998. Danny Brazil, who died in September 1999, a few days short of his 90th birthday, had a good version of this ballad, which Mike Yates recorded. I’m also pretty certain that, if one knew where to go, it could still be recorded in this new millennium.

I love this atmospheric recording: an ancient ballad being sung as big trucks roar past on the road outside; then an altercation with a drunk at the other end of the bar - but Denny just carries on regardless.

19 Riding Along on a Free Train (Roud 16143) / Mother’s the Queen of my Heart (Roud 16144) (both sung by Wiggy Smith)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at Wiggy’s caravan, Elmstone Hardwicke, 18th November, 1999)

I curse and I swore at my father

I curse and I swore at my father

And I told him his words was a lie

He called me a drunkard and a gambler

Not fit to be called his son.

So I packed all my clothes in a bundle

And I went to wish mother goodbye

My poor mother broke down a-crying

Saying, “Oh, my son, my son, do not leave.”

Now I’m riding along in a free* train [* freight?]

And I’m bound for nobody knows where

I only left home just this morning

And my heart is heavy with care.

“Now, Son, here’s a wanderer’s warning

Don’t break your poor mother’s heart

Stay by her side, for she needs you

And all her life long she’ll agree.”

Mother’s the Queen of my Heart

Now I started gambling for pastime

At last, I was just like them all

I lost my clothes and my money

Nothing was left to be seen

I saw my dear Mother’s picture

And somehow she seemed to say

Son, you have broken your promise

And the promise you broke, you must pay.

For the cards was dealt all round the table

Each man took a card on the draw

I drew the one that would beat them

One card - and that was a Queen

All my winnings I gave to a Newsboy

And at last, I was just like them all

But I’ll never forget that promise

That my Mother’s the Queen of my heart.

All we can tell you is that these are a pair of Jimmie Rodgers songs, which were both learned from records.

20 Barb’rye Ellen (sung by Wiggy Smith) (Roud 54, Child 84)

(Recorded by Gwilym Davies and Paul Burgess at The Victoria pub, Cheltenham, Glos, 9 October, 1994)