Fiddles! Fiddles! Fiddles!

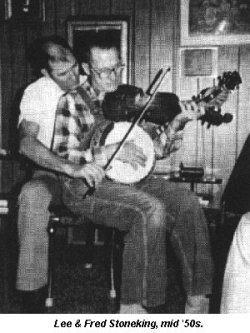

I grew up listening to these fiddles all day and all night and all morning and at noon and every time in between. Many nights I'd fall asleep to the sound of fiddles and wake up to find my dad still a-playing. Or maybe he'd go to sleep himself and get up early and start all over again.

And it wasn't just my dad, because this kind of music just runs in our family. My nationality is Irish, Scottish and English - and I've heard that way back somewheres we were court musicians with a coat of arms.

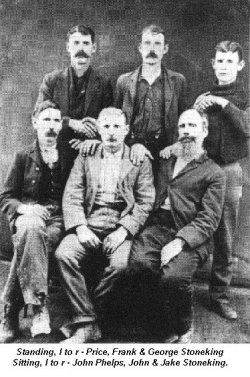

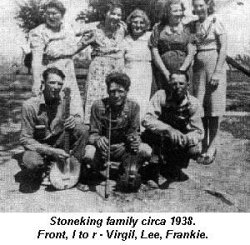

Anyway, my mom was a decent fiddle player and her father was a banjo player too. My granddad on my dad's side of the family was named Frank Burgess Stoneking and he always said that he was The Best Stoneking Fiddle Player. But Granddad had four other brothers and each of there claimed to be The Best Fiddle Player as well - I don't know how they worked that out between them.

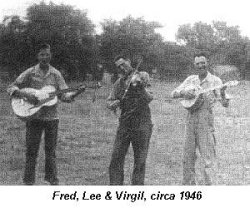

Coming down to my dad's generation he had four brothers and all them boys played the fiddle. Even my aunts could saw you something on a fiddle. But every last one of them played the piano and those old pump organs for rhythm and could pound on banjos. As to me, all my brothers play fiddles, all of them play guitars and all of them play banjos. And that's pretty much true of my sisters too.

And it seems like that they all married people that played, too. At the last Stoneking Reunion, there were so many strings there, it was like we had our own Bluegrass festival.

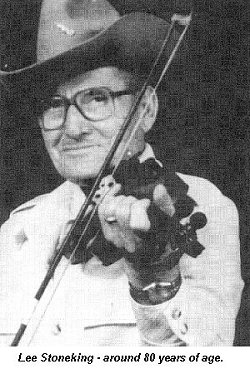

So you might consider that I was simply raised with the fiddle. My dad, Lee Stoneking, was a farmer. I was born at a little old town by the name of Chilhowee up in Johnson County, Missouri. It's about twelve miles north of Clinton as the crow flies. We had forty acres of row crops, but, after all the kids got big enough to actually help, Dad started renting about another one hundred fifty acres more. We all worked hard - my sisters could plough corn just as good as anyone. Cultivating and shucking corn - I just loved that. And we did it all with six head of horses. Boy, I must have walked a million miles behind horses, ploughing ground, by the time I was ten years old. You know, you can learn a lot when you're out in the middle of a forty acre pasture, following along behind a walking plough. You've got the whole world to think in and you can see it all around you. Of course, sometimes you'll start daydreaming. You'll think everything's all right, but then you'll hit a stump out there. When that happens, the horsed jerk you right over the plough, because you've got the lines tied around your belly. That'll wake you up, I guarantee you. There were many times I must have ploughed and been asleep because I didn't remember nothing after.

So you might consider that I was simply raised with the fiddle. My dad, Lee Stoneking, was a farmer. I was born at a little old town by the name of Chilhowee up in Johnson County, Missouri. It's about twelve miles north of Clinton as the crow flies. We had forty acres of row crops, but, after all the kids got big enough to actually help, Dad started renting about another one hundred fifty acres more. We all worked hard - my sisters could plough corn just as good as anyone. Cultivating and shucking corn - I just loved that. And we did it all with six head of horses. Boy, I must have walked a million miles behind horses, ploughing ground, by the time I was ten years old. You know, you can learn a lot when you're out in the middle of a forty acre pasture, following along behind a walking plough. You've got the whole world to think in and you can see it all around you. Of course, sometimes you'll start daydreaming. You'll think everything's all right, but then you'll hit a stump out there. When that happens, the horsed jerk you right over the plough, because you've got the lines tied around your belly. That'll wake you up, I guarantee you. There were many times I must have ploughed and been asleep because I didn't remember nothing after.

Anyways, I was born way back in the prehistoric days of 1933. I was the youngest of four kids that my mom and dad had before they separated way back yonder. Then my dad married a woman that already had three girls. One of them was the exact same age of me, so we were raised as twins. And then my dad and my stepmother had six more kids. Boy, I'll have to stop and think just how many brothers and sisters I had, because my mom had three more children with her next husband. Well, however many it was, we all got along great. We had a great big long kitchen table, with a big long bench up one side and another big bench down the other. Dad sat at one end and Mom at the other. They'd hand the plates all around and there'd be one big stew kettle sitting in the middle of the table. Generally it was beans, cornbread and green onions. Dad would lift the pan off the stew kettle, and he'd ask, "OK, who wants beans?" And it was, "Me, me, me, me, me, me" up and down that table.

My dad didn't get electricity in our house until I was fifteen years old. We used to separate our cream by hand. Boy, I have turned those old cream separators for hours on end - it would positively wear you out. We never bought butter either; we'd just put the cream in a gallon fruit jar and swished it around; it made the best buttermilk in the world. If you wanted eggs, you'd go right out to that chicken house and get them. And they were bright yellow orange, wasn't any of that pale yellow stuff that you get now. Then you went out there to the smokehouse and you cut the rest of your breakfast right off the ham.

Then there were the butchering days they were always a lot of fun. Two of my uncles and Dad would always butcher together. Sometimes they'd butcher six or seven hogs, which would be an all day job, but they always had a threshing crew there to help. They had three big vats and my job was to keep that fire a-woofing all day You'd grind them old cracklings up and sprinkle them in cornbread - gosh, that was good. Boy, them's good days; I feel sorry that my kids missed out on some of those times. I could do every thing in the world to try to get them to relive those days, but it'd be impossible - that part of the system is all gone now. It's against the law to butcher your own hogs; you've got to let the licensed man do it. you can't even churn butter no more because the cream ain't to be found. All the chickens is caged up - there's hardly anybody that's got chickens and chicken houses any more. They might have a few old hens running around, but they'll be too old to lay eggs.

Thinking of that reminds me of a story about my Uncle Young. There was a man named Al Brunker who'd retired from Kansas City and bought a couple of acres right next to my uncle. One day Uncle Young told him, "Al, I've got some hens to butcher if you'll help me, I'll send you up a nice young tender fryer, so you can cook it up for you and your wife tomorrow." So Al came down and helped him. The next day Uncle Young caught a little banty rooster they had and you know that they're tougher than shoestrings. He dressed that rooster out and took him over to Al s with his legs sticking up in the air and said, "Here's that nice young fryer that I promised you." Mrs Brunker said, “Thank you very much, Young. We'll eat it and think of you."

The next day Al come over "Young, you know that chicken you gave us ?" "That nice young fryer?" Al said, "Yeah. You know my wife fried that for an hour, and she couldn't even stick a fork into the leg. So she fried it for another hour, but it just kept a-getting tougher. Then we put it in a broiler for about three hours. But that didn't help, so we finally had to give that to our dog. And you know," Al said, "he's still a chewing on it." Well, that just set my uncle to pounding his legs, because he knew exactly what he'd done. You'd have enjoyed meeting my family. Some of them was just hilarious and they loved to pull pranks on each other.

One time one of my great uncles, Uncle Ben, came over when a little stray dog had come around our house. Uncle Ben said, "I'll take that dog. I get so tired of getting up on brush piles and stomping out the rabbits. By the time I catch my balance and see a rabbit, it's too late. So I'm gonna make a rabbit dog out of that dog." So he took the dog and named him Blackie. After that, wherever you seen Uncle Ben, you seen old Blackie, and wherever you seen Blackie, you seen Uncle Ben.

One time one of my great uncles, Uncle Ben, came over when a little stray dog had come around our house. Uncle Ben said, "I'll take that dog. I get so tired of getting up on brush piles and stomping out the rabbits. By the time I catch my balance and see a rabbit, it's too late. So I'm gonna make a rabbit dog out of that dog." So he took the dog and named him Blackie. After that, wherever you seen Uncle Ben, you seen old Blackie, and wherever you seen Blackie, you seen Uncle Ben.

But one time Uncle Ben come across the pasture, his old rifle over his shoulder, but no dog. He come up in the yard, and Dad asks, "Uncle Ben, where's old Blackie at?" Uncle Ben replied, "Well, I could never make him stop running. He'd always beat me to the brush pile and have all the rabbits run off before I could possibly get there. And so, mmmm, pbt!" that old chewing tobacco, you know -"old Blackie's gone to heaven."

You know that tune I call The Honey Creek Special? Well, Honey Creek was a little old drawl up by my dad's farm. The bridge across it was pretty long and had real rickety boards on it. So if you heard a Model A coming across that old clatterty bridge, you knew that it was either coming to see the old bachelor that lived near us or coming to our house. Nine out of ten times, it was coming up for fiddling. So we got to considering that bridge a special kind of bridge on account that it would let us know that someone was coming to our house. So the Honey Creek Special let us know that we're gonna have company in about fifteen minutes.

Square dances used to be very common in that part of the country. Just a bunch of old farmers would get together to have a dance in their homes. They would dance in two rooms and you'd always play right in the doorway. And they'd always bring the food out when they'd take a break. Boy, that was so good: everything was made right there in the skillets on an old wood stove.

Dad used to play a square dance a week in the little old town in Urich, over in central Missouri. There was enough room in there to have seven sets and each set had its own caller. One set might be doing "divide your own ladies, gents go haw" and another one might have been doing the grapevine twist. A lot of times the caller would dance in his own set, just yelling out the calls. Anytime I could get away from playing and had a chance to square dance, I always wanted to dance in the set where my uncle Young was calling, because he had a good sharp voice that would cut through the air like a pocket knife, and he would sing his calls the way through, from start to finish. That just made it all livelier. There ain't nobody to do anything like that nowadays. Instead, there'll be one man standing up there with a microphone yelling for ten or fifteen sets - and using records, by gosh.

There's another little town called Deepwater that had two little dance halls and many a Saturday night, me and some of my brothers would play in one place and maybe Dad, one of my uncles and my other brother would play right across the street, and the people would just drift back and forth between us. Of course, sometimes there'd be trouble. Now, my dad wasn't a nonsense type of guy and he didn't like drunks breathing on him. This one old boy had walked in a dance when the set had already started and that made him mad. He put his hand around the neck of Dad's fiddle and said, "If I can't dance, there'd ain't nobody gonna dance." Naturally, that stopped it. Dad just set the fiddle down quietly and pulled out a pocket knife out of his pocket and went, "Clip!" - he snipped oft a hunk of the man's ear. He said, "Now, you get away from here and don't bother me no more." And that solved that problem.

There's another little town called Deepwater that had two little dance halls and many a Saturday night, me and some of my brothers would play in one place and maybe Dad, one of my uncles and my other brother would play right across the street, and the people would just drift back and forth between us. Of course, sometimes there'd be trouble. Now, my dad wasn't a nonsense type of guy and he didn't like drunks breathing on him. This one old boy had walked in a dance when the set had already started and that made him mad. He put his hand around the neck of Dad's fiddle and said, "If I can't dance, there'd ain't nobody gonna dance." Naturally, that stopped it. Dad just set the fiddle down quietly and pulled out a pocket knife out of his pocket and went, "Clip!" - he snipped oft a hunk of the man's ear. He said, "Now, you get away from here and don't bother me no more." And that solved that problem.

Sometimes I used to hear so much music, it'd begin to drive me up the wall. But when I was over in Korea in 1952, I really missed it. My dad and my twin sister Bertie got hold of all old wire recorder, made some recordings and took them some place to be changed into records. They must have been made out of cardboard or something, because they were soft and real thin. Of course, it took a month for me to get them and the salt air must have gotten to them during the trip over to Korea for they were wrinkled very badly. We had a little old cheap record player that was broken but its sound still worked. So I used to turn the record around myself with my finger, round and round and round. I'd get her going up and down the hills on one of them warped little records. Bertie talked to me a little bit between the tunes and sometimes she would sound like Donald Duck and sometimes she'd sound like a gruff talking old man. But every once in a while, it'd sound just like my sister Bertie. And, directly, you could get that record turning just right and that old fiddling would come out just as plain as day. Boy, the hairs would stand up on my arms to hear it. I absolutely whirled those records around so many times that I eventually wore them clear out.

I wrote Dad that I was really needing something to play on bad. I couldn't play the fiddle then, but he sent one to Korea. I did manage to play a little bit of several different tunes, but one night I come in from duty and I noticed little sprinkles of wood on my bunk and all around the whole area which was mine. I'm afraid somebody didn't appreciate my fiddle playing.

I had loved airplanes when I was a kid. I could tell you the kind of airplane from the drone of its engine. So I joined the Army and signed up for the Airborne, hoping I could be next to airplanes. But then for months and months and months, the only time I saw an airplane was to jump out of it - get in it and jump out. I didn't get to go hardly nowheres, which was a big downfall for me. But I still love airplanes. In any case, after I was discharged, I worked for a year for a rancher in California. Then I spent twelve years in Arizona, but finally decided to settle back here in Missouri and bought a place up near Clinton. It ain't much of a place, but it's a spot to go fishing and I like doing that a lot.

I always had a good time with Dad when we went out on these fiddling episodes. I've played guitar and banjo all my life and have been to absolutely hundreds of contests. I used to play with my grandfather, Frank Burgess Stoneking, when I was seven years old. But he played so terrible fast - way too fast for a learner. Boy, I remember them black snappy eyes looking at me when I'd done something wrong or I was lagging a little bit. But Grandpa was a great fiddler, and so was Uncle Jake and Uncle John and Uncle George and Uncle Price - all of them. But I didn't get real serious about my oven fiddling until the early 'sixties. I was playing rhythm for my dad at a contest and he won a hundred dollar first place and he did it in about ten minutes. I thought to myself, "Boy, how easy!" So I started really to practising, and finally, I won my first fiddling contest in 1966 at a little town called Lamont. I won a first place ribbon and a brand new twenty dollar bill.

I beat my Dad in that contest and nowadays it's happening to me. Both of my children have turned out to be real good fiddlers. Alita and Luke have both have won Missouri Junior Championships. The first time Alita beat me, she actually cried. She said, "Here, Dad, you won this trophy; I didn't." I didn't see it like that because I know when I'm beat. So I told her, "Now, Alita, don't you feel bad - you beat me fair and square. I was trying my best to win and it just tickles me to death to have one of my kids beat me doing something that I'm trying my best to do. So whenever you do win, you'd earned it. From now on, whatever the judges award you, you walk right up there just as proud as you can be, whether it's for first or last place.”

I beat my Dad in that contest and nowadays it's happening to me. Both of my children have turned out to be real good fiddlers. Alita and Luke have both have won Missouri Junior Championships. The first time Alita beat me, she actually cried. She said, "Here, Dad, you won this trophy; I didn't." I didn't see it like that because I know when I'm beat. So I told her, "Now, Alita, don't you feel bad - you beat me fair and square. I was trying my best to win and it just tickles me to death to have one of my kids beat me doing something that I'm trying my best to do. So whenever you do win, you'd earned it. From now on, whatever the judges award you, you walk right up there just as proud as you can be, whether it's for first or last place.”

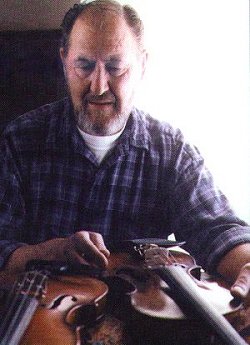

When my dad was coming up, there weren't that many fiddling contests but, since this Missouri Old Time Fiddler's Association came in, there's a kind of summer circuit and, if you are truly a good enough fiddle player, you can make a powerful good living just fiddling. But you're gonna have to travel around in big vicious circles to do it. That's too hard for me. I like to go to contests, but I'd rather make fiddles and repair instruments than do all that travelling. The way I figure it, some people pay me to fiddle and some people pays me not to fiddle, so it really don't matter if I'm playing for money or not.

Now I have been beat by the best and I have been beat by the worst. Whatever happens, I've never opened my mouth to complain, because I think that's senseless. But some people take it all so seriously. My dad and I were fortunate enough to have been invited to the North American Championship Invitational up in Nebraska. Well, one so-called ''famous fiddler' drove all the way up there, but when he saw who else was there, he turned around and drove all the way home. Then another so-called 'famous fiddler' showed up and, after he paid his fees, told the people running the contest that, since he always furnished one of the judges, so they could stop looking for anyone else. He'd brought his own judge up from his state free of charge. Needless to say, his judge didn't get to judge that particular contest.

Fiddlers will play a lot of tricks on each other so that they can win. If someone knows that a contestant's apt to beat him he might take him out and give him a drink. If he accepts that first one, then the other guy'll try to fill him up as much as he can. Alter that, when the poor fiddler gets on the mike he'll be bound to make a mistake. I saw a guy one time who had been nipping pretty heavy and he played 'Bill Cheatham' for his hoe-down and he done a good job, too. And then he announced some other piece for his tune of choice, but, when he started to play, by George, it came out 'Bill Cheatham' again. And he did a good job that time too, but, needless to say, he got black-balled.

There's a couple of Missouri fiddle players, both of them top-notch. I love them both for their fiddling ability, but I'm afraid they used to be crooks. They'd meet up at these contests, and one guy'd say, "Boy, Joe, you sure got a good sounding fiddle, and you got a good bow there, too." Old Joe'd say, "Yeah, John," and he'd talk about how much money he had paid for it. Then John would say, "Well, let me borrow that now. I just want to play it a little bit to see what it is like." While Joe wasn't looking, John'd run his hand through his hair, get a little hair oil on his hand and rub that bow down. Eventually John'd hand it back to Joe, but he didn't know that Joe was doing the same thing to him. At this one contest I went to, I remember both them boys getting up to the microphone and just going "ssss, ssss." They were both dandy fiddle players, but there were always playing these pranks on one another.

I'm afraid not all the judges are totally honest either. I've been a judge in a contest where the head judge started telling who was going to win before they even started the contest: "This guy's gonna win, that guy's over there's gonna get second..." and so on down the line. And, by gum, it actually turned out to go that way. Thinking about the score sheet I had turned in, I imagine that the head master must have been a whiz at juggling figures.

But who knows who's the best fiddle player or who's the worst? it's just whatever is pleasing to your ear. But some people take music so seriously. I was eating dinner across from a guy who's a famous musician in Nashville. I was having trouble getting a conversation going. I'd ask him, "Do you like to go fishing" and he'd say, "Nope". "Well, you going to watch the Super Bowl ?" "Nope". The he laid down his fork and looked at me real serious and said, "Look, I'm a musician. All I do is play music. All I think about is music. And that's all I'm going to talk about too." So that kind of stopped the conversation right there.

My dad was a big fan of this old man from Texas that had a young son and daughter who played rhythm for him. We asked if we could listen to them practice before this contest, and he said it was all right if we'd keep quiet. So we went to his room and after they'd finished practising, my dad called out to him, "It's no wonder that you're such a fine fiddle player. You've got the best rhythm in the world here in these kids." That old mad got real mad and started cussing my father, "You guys are gonna have to leave right now. I told you to listen and not talk." I didn't like him talking to my Dad like that set I asked him what was the matter. And he said, "Well, if you go to bragging on these kids, they'll get the big head and they'll slack down with their work on their instruments." So we all left, but I don't think any of us was quite the fans we were when we went in.

My dad was a big fan of this old man from Texas that had a young son and daughter who played rhythm for him. We asked if we could listen to them practice before this contest, and he said it was all right if we'd keep quiet. So we went to his room and after they'd finished practising, my dad called out to him, "It's no wonder that you're such a fine fiddle player. You've got the best rhythm in the world here in these kids." That old mad got real mad and started cussing my father, "You guys are gonna have to leave right now. I told you to listen and not talk." I didn't like him talking to my Dad like that set I asked him what was the matter. And he said, "Well, if you go to bragging on these kids, they'll get the big head and they'll slack down with their work on their instruments." So we all left, but I don't think any of us was quite the fans we were when we went in.

Being around all these fiddle players, you hear a million stories. 'they used to tell how Clayton McMichen, the guy who played on those Skillet Licker records, used to travel around with a black man. They'd ride into a strange town together. McMichen would spread the word that "There's a black man here that says he's a better fiddle player than me. You guys come on down to the theater today - it'll only cost you a dime - and we'll see which one of us is better." They'd play on the peopled prejudices and then split the money and leave town together. Somebody once told me that McMichen was quite a scrapper - he'd have to have been if he was into that kind of racket.

There's a story on this fiddle tune Saddle Old Spike. Back in the 'twenties, there was a guy by the name of Lum Varner and he had a younger heather called Jim. When Lum as about twenty years old, he made up this tune and called it Saddle Old Kate. But those brothers had a little fall-out on account of being jealous of each others fiddling ability. So they parted company. The problem was that Jim loved that tune too. He was so mad at his brother that he called the tune after his own horse which was Spike. A friend of mine named Joe knew Jim and that's how it came down to me as Saddle Old Spike.

Getting back to contests, the man that taught me more on the fiddle and done me more good than anyone else is a fiddler by the name of Pete McMahan. Pete has the best expression with his bow that you ever heard and the most solid time. I played rhythm for him for many years, all over the place. Pete Mac would call me up, "Fred, let's go to such and such place," you know. And Pete was always good about paying his rhythm people. Some fiddlers used to just take us for granted, but Pete always paid twenty percent of his winnings to his rhythm. And after that got ahold, I played for another great fiddle player, Cleo Persinger, and for Jake Hockmeyer from Spokane, Missouri, who's the finest left-handed fiddle player I ever heard. And I played for the Wells boys from Booneville. Many times I made more money with the guitar than I did the fiddle. I could always get in the money, but winning came slow for me. But I could always do pretty well with my guitar.

I worked as a welding foreman for eighteen and a half years up near Clinton. But that job simply shut down and moved off, which really hurt me. Then I worked as a field foreman for an alfalfa company out in Nebraska, but that was just seasonal work. Then my wife needed some more college to get her nursing degree, so we came down to Springfield to see about the School of the Ozarks. Now I didn't have a job, so I put my fiddle under my arm and I went out to Silver Dollar City in Branson and told them I was a fiddle player. I played for them and they said, "OK, come to work in three days." So I worked down there for a lot of years.

I played with the best group I ever played with, called the Horse Creek Band. It was unique in that we never played a set show - it was all requests and everything was by ear. Each of us knew exactly what we could do. It'd all be: "Who knows such and such song?" "I do." "Well, start her off." Boy, that would keep you on your toes, because you never knew what you were going to play. I don't think we had hardly ever had to turn down anyone's request. It was all country and old-time with some bluegrass and a lot of gospel thrown in: George Jones, Ernest Tubb, and so on. We didn't have a female singer, so we really couldn't do Kitty Wells stuff, but that didn't keep some of us from trying. Ha! Ha!

That was just when Branson was beginning to build up, though it was absolutely nothing compared to what's it like now. One of the main reasons I don't work with the fiddle down in that area anymore is the traffic. I used to get off work at Silver Dollar City and I was supposed to drive a mile and a half down to the Shepherd of the Hills theatre, where they had me playing "Fiddlin' Jake." It would take me a full hour to drive a mile and a half - it would have been quicker if I could have walked.

So when my wife graduated and got employment in Springfield, we moved into town where I've been building fiddles and doing a lot of repair work.

So when my wife graduated and got employment in Springfield, we moved into town where I've been building fiddles and doing a lot of repair work.

Anyway, you can now understand how I grew up. It was all fiddling, all music and hardly any problems. Just a family thing, I guess. And that's why I like to take my kids off to these fiddle contests - we'll go over to Oklahoma, up to Kansas and Nebraska and into Iowa, and down into Arkansas, because we've got a lot of good friends in all those places. After we leave a big contest, I swear I'll hear fiddle tunes in my head for three full days afterwards.

But at least I won't end up like this old man I once saw interviewed on television. He claimed to be a fiddle player and said, "Yeah, I used to play three tunes pretty good. But one of them I got to disliking, so l quit playing it back fifteen years ago. And the second one, I forgot it. And I'm not sure if I've got the one I play quite right either." Boy, that'd left him in a dickens of a mess. Now I ain't the man I used to be, and I never was, but I hope I'm doing a little bit better than that old man.

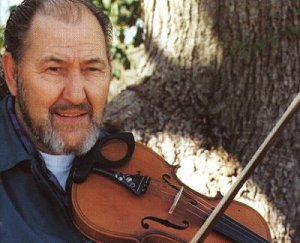

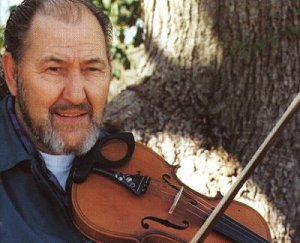

Fred Stoneking - 8.11.97

This article first appeared as part of the Insert notes of the CD Saddle Old Spike: Fiddle music from Missouri - Fred Stoneking, on Rounder CD 0381 - and is used by kind permission of Rounder Records. A review of this record can be found in these pages.

Article MT008

| Top of page | Home Page | Articles | Reviews | News | Map |