Article MT204

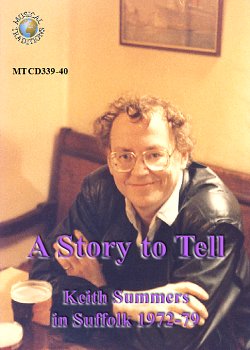

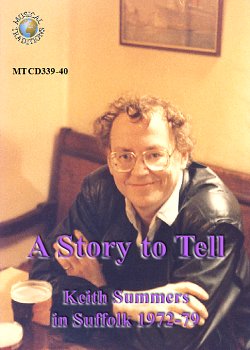

A Story to Tell:

Keith Summers in Suffolk 1972-79

Musical Traditions Records' third CD release of 2007: A Story to Tell: Keith Summers in Suffolk 1972-79 (MTCD339-0), is now available. See our Records page for details. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the record, or who might find the small print hard to read, I have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here.

[Track Lists]

[Introduction]

[In His Own Words]

[The Performers]

[CD One]

[CD Two]

[Credits]

CD 1:

1 -

2 -

3 -

4 -

5 -

6 -

7 -

8 -

9 -

10 -

11 -

12 -

13 -

14 -

15 -

16 -

17 -

18 -

19 -

20 -

21 -

22 -

23 -

24 -

25 -

26 -

27 -

28 -

29 -

30 -

31 -

32 -

33 -

34 -

35 -

36 -

37 -

|

Doing My Duty

Abie My Boy

Blow the Candle Out

Highwayman and the Farmer's Daughter

Coal-Black Mammy

Talking about learning songs

Three Jolly Sportsmen

Green Bushes

Maggie May

Mary Anne

Soldier's Joy

All Tattered and Torn

The Nutting Girl

The Kildare Fancy

The Ship I Love

I'm a Man you don't Meet Every Day

Step Dance Tune

The Parson's Creed

Cock of the North / Pop Goes the Weasel

The Seeds of Love

The Drowned Lover

The Lincolnshire Poacher

Talking about his grandfather

Fairy's Hornpipe and dancing doll

You Can Look but you Mustn't Touch!

Wild Flowers

The Yellow Handkerchief

Poem

The Rakes of Mallow

The Baby's Name

The Flowers of Edinburgh

The Roving Gypsy

Talking

Polka(Jingle Bells)

Australia

The Female Drummer

The Sailor's Hornpipe

|

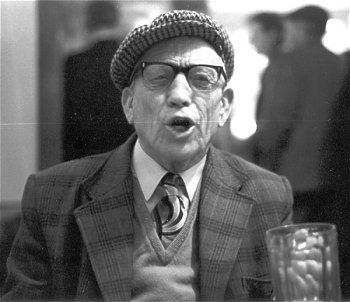

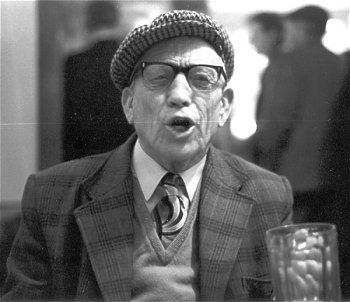

Ted Cobbin

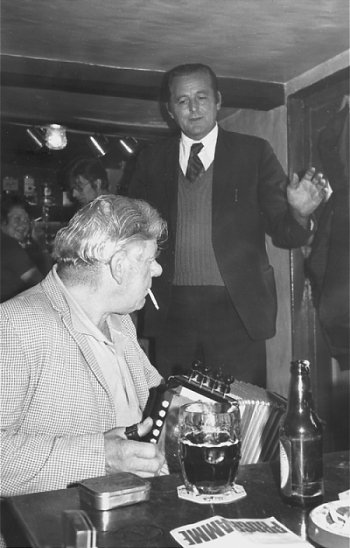

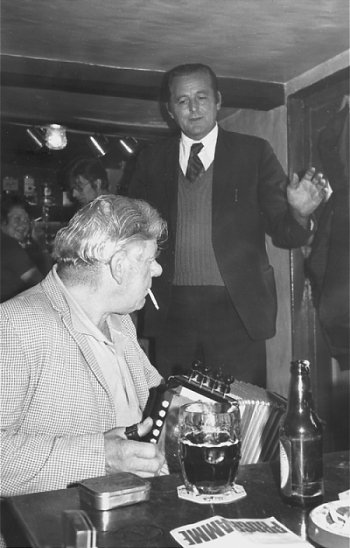

Ted Cobbin and Peter Plant

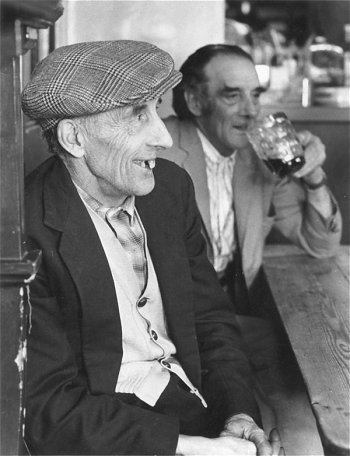

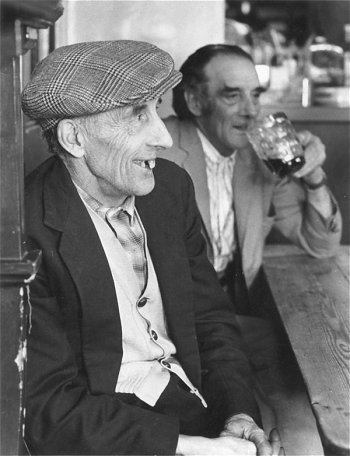

William 'Jumbo' Brightwell

Alec Bloomfield

Fred Pearce

Cyril Poacher and Geoff Ling

Bob Scarce

Geoff Ling

Geoff Ling

Arthur 'Spanker' Austin

Fred List

Percy Ling

Cyril Poacher

Fred 'Pip' Whiting

Fred 'Pip' Whiting

Alec Bloomfield

Peter Plant

William 'Jumbo' Brightwell

Tommy Williams

Alec Bloomfield

William 'Jumbo' Brightwell

Billy List

George Ling

Fred 'Pip' Whiting and Cecil Fisk

Jimmy Knights

Alec Bloomfield

Cyril Poacher

Harkie Nesling

Harkie Nesling

Harkie Nesling

Fred 'Pip' Whiting

Fred 'Pip' Whiting

Harkie Nesling and Fred 'Pip' Whiting

Harkie Nesling

Cyril Poacher

Bill 'Dodger' Brabbing

The Peacock Band

|

3:05

0:57

2:44

3:03

1:10

3:50

5:25

3:29

2:49

0:40

0.36

3:25

3:02

1:14

2:23

1:42

0:57

1:15

0:41

4:04

3:39

1:38

1:06

2:02

2:07

2:29

3:31

0:34

0:47

1:29

1:28

2:50

1:05

1:15

2:05

2:05

0:57

| | | | Total: | 79:51

|

CD 2:

1 -

2 -

3 -

4 -

5 -

6 -

7 -

8 -

9 -

10 -

11 -

12 -

13 -

14 -

15 -

16 -

17 -

18 -

19 -

20 -

21 -

22 -

23 -

24 -

25 -

26 -

27 -

28 -

29 -

30 -

31 -

32 -

33 -

34 -

35 -

36 -

37 -

38 -

|

Truly Fair

The Recruiting Sergeant

Strolling down to Hastings

Chinaman

Pigeon on the Gate

The Lobster

Old General Wolfe

A Broadside

Unidentified Tune

The Flower of London

The Indian Lass

Oscar's Waltz / Charlie Philpott's Waltz

Out with my Gun in the Morning

Talking

Duckfoot Sue

Talking

Wormwood Scrubs

Phil the Fluter

Paddy and the Rope

The Oak and the Ash

Sailor's Hornpipe

Lamplighting Time in the Valley

Step Dance Tune

Pretty Little Mary

The Next Song in the Programme

Sailor's Hornpipe / Pigeon on the Gate

Old Brown sat in the Rose and Crown

Cock of the North

Talking about The Ship

The Burden of the Spray

The Maid and the Magpie

Red Sails in the Sunset

Unidentified Tunes

The False Hearted Knight

Young George Oxbury

The Barndance

The Morals

Jim the Carter's Lad

|

Font Watling and Wattie Wright

George Ling

Aileen Stollery

Aileen Stollery

Font Watling and Wattie Wright

Percy Ling

Alec Bloomfield

Bob Scarce

George Woolnough

George Dow

William 'Jumbo' Brightwell

Reg Reeder

Jimmy Knights

Jimmy Knights

Jimmy Knights

Jimmy Knights

Jimmy Knights

Tommy Williams

Billy List

Charlie Whiting

George Woolnough

Cyril Poacher

Oscar Woods

Percy Ling

Albert Smith

Albert Smith

Albert Smith

Fred Pearce

Cyril Poacher and Geoff Ling

Bob Scarce

Cyril Poacher

Fred Eley Whent

Fred Eley Whent

William 'Jumbo' Brightwell

Alec Bloomfield

Fred List

Alec Bloomfield

Ted Cobbin with Peter Plant

|

0:35

1:42

1:44

1:28

0:40

2:11

3:07

3:34

1:12

3:36

2:46

3:03

3:04

0:46

1:46

1:32

3:23

0:54

2:42

3:25

0:52

4:02

0:53

2:57

0:16

0:26

0:28

0:52

1:12

4:20

2:59

1:14

1:25

4:47

2:07

1:06

2:04

2:37

| | | | Total: | 79:58

|

|

|

Traditional Songs and Music from Suffolk, recorded by Keith Summers, 1971-1979

[It was my] great good fortune to have met, in such a short period, so many thoroughly genuine, fascinating and talented people ... they all had a story to tell. I would like to think that I did my best to tell it.

Keith Summers, 1999

I visited Keith in his bungalow in Southend in October 2003 and again in January 2004. These were social visits, a chance to talk about old times, and to record Keith talking about his life and his recording of traditional music and song.

Keith had initially made recordings just for his own pleasure. Self-funded and usually working alone, he spent much of his spare time during the 1970s travelling around Suffolk. He got to know well and recorded many of the traditional singers and musicians that still formed an important part of the social life of an area.

Thanks to Keith’s efforts, and his awareness that this unique material was in danger of being lost, a wealth of ballads, topical songs and stories as well as dance music, step-dancing and popular music, recorded in public houses and in homes and cottages, has been documented and preserved.

Some of his Suffolk recordings had been issued. Sing, Say and Play and The Earl Soham Slog were released by Topic records in 1978. He later had some tracks included on The Voice of the People, Topic’s 20 CD set, issued in 1998.

Keith’s original tapes had been deposited in the National Sound Archive, as part of their Traditional Music in England Project. In return he had CD-R copies.

Although very unwell, he had been planning a double CD of his Suffolk field recordings. Keith had spent many hours listening to his recordings, some of which he hadn’t heard for over thirty years, and had made his selections. He was particularly excited about the prospect as he had selected many of his earliest recordings. These early performances were recorded on non-professional equipment in less than ideal conditions but they captured local singers and musicians entertaining a very lively and appreciative company.

Sadly Keith didn’t live to bring these CDs to fruition. In accordance with his wishes, John Howson issued Good Hearted Fellows (Veteran VT154CD) in 2006 using tracks from those that Keith had intended for his double CD. I have added to the tracks that remained to make up this double CD; my selections are marked*. I have also edited and cleaned up tracks where needed.

Keith Summers became ‘seriously interested’ in listening to music when he was about 12. His introduction was the skiffle music of Lonnie Donegan. He later heard Blues music and started to collect obscure LPs which were imported from the US. His tastes broadened as he discovered American Old Timey and Scottish and Irish traditional music which was then becoming available on record. Keith soon developed a keen ear for the ‘real thing’.

At the age of about 15, on a regular trip to Collett’s record shop, London, Keith was given a record to listen to from the 10 LP set of the Folksongs of Britain series just released by Topic Records. It was to prove life-changing.

The following, entirely in Keith’s own words, is taken from a recording that I made during my visit to him on 10/10/03

I was in Collett’s and Hans Fried - who always pointed me towards things that I might be interested in - said, “Listen to this. It’s got some Irish stuff on it. It’s also got a lot of Scottish and few tracks of English”. I said, “English? What do you mean by English?” He said, “English folk songs”. Of course my initial reaction was Do you Ken John Peel, played by the school music teacher. I thought “Oh gawd!” but I said, “OK I’ll have a listen”. As luck would have it he gave me one that had three or four tracks from Blaxhall Ship on it. I whacked those on and I thought “Bloody hell, I’ve never heard anything like this before.”

I started reading the notes and there was absolutely bugger all on these notes to give any information about the background to the singers. There was background to the songs, which I wasn’t particularly interested in. I’m not a folksong collector and I’ve never pretended to be. I haven’t got a great deal of interest in the songs I’ve collected. I’ve got no problems with people who have, but it’s not my main interest. I’m interested in the singers themselves. Why they’ve kept it going and how they’ve kept it going through singing in pubs, at home singing to their families. That’s what interests me, but primarily singing in pubs. As I later found out - in Suffolk in particular - there was a network of these pubs where the musicians used to go. The singers didn’t - they didn’t used to travel out of their villages - but the musicians would go and entertain. It was fascinating.

So I started delving around to see if I could find out anything about English traditional singing and Blaxhall Ship in particular. This would have been I would guess around '67/68. I was about 20 then. I remember once they had a sale at the Cecil Sharp Folk Shop where every magazine was one penny, old money. I must have bought 200 copies of Sing Out, Bluegrass News, etc. I don’t know how I carried them all home on the train, but I did. Amongst them there were one or two magazines which carried articles on English traditional singing but again no background to it at all. I thought no more about it, to be honest. I’d been to a couple of folk clubs by then. One in Rochford and there was a good one at Benfleet, which was just down the road. Not because I was particularly interested in folk music but it was a social event. At that time it was on the arse end of the folk boom. Me and a couple of mates used to go really just for a social do. We saw people like Anne Briggs. I found some of the traditional stuff really hard work - because I can’t concentrate on the words of songs at all - and I found some of it rather dour, rather dull. Some of it was very good and I particularly liked people like the Young Tradition, because it was in-your-face, quite catchy and didn’t take a lot of thinking about. They did allude to the tradition, particularly Peter Bellamy, and Harry Cox and Sam Larner. It didn’t mean anything to me but gradually you’re getting a little background. There was Sam Larner, who was recorded in the ’50s and died in so and so, or Harry Cox who died in so and so. But you didn’t know anything about them.

Because I was quite interested in it - again this would have been 1969 I think, I would have been 20 - I did something surprising and a little bit daring for me, bearing in mind I was extremely shy in those days, painfully shy. I booked up to go to the National Folk Festival at Loughborough University. Primarily to see people like Lizzie Higgins, Stan Hugill and Na Fili. It was primarily Irish and Scottish people I went to see but there was a singer on there called Percy Webb. I got chatting with him in the bar. I’d just bought this very cheap portable reel to reel recorder to record some of this stuff at the Festival and some of the Irish stuff in London I was listening to. I said to Percy, “Would you mind if one day I came up and saw you and recorded some of your songs?” He said, “Yeah by all means do that”. He told me where he came from. It was Tunstall Common. So I went up there.  I didn’t have a car at that time so I went by train. I got off at Wickham Market station, which is actually the village of Campsea Ash. It was about a three mile walk to Tunstall and as I was walking to Tunstall I saw signposts for Blaxhall. I’d never known where Blaxhall was. It was so small it didn’t appear on any of the maps I had. When I saw it I thought “Bloody hell, that’s Blaxhall! That’s where those recordings were made.” I went on up to Tunstall and recorded Percy Web for an afternoon. I recorded about half-a-dozen songs off of him and then I said, “Percy, when I came up here I noticed there was a sign for Blaxhall”. I said “Have you ever sung in Blaxhall Ship?” He said, “Oh yes in the old days I used to sing in there quite a lot, boy”.

I didn’t have a car at that time so I went by train. I got off at Wickham Market station, which is actually the village of Campsea Ash. It was about a three mile walk to Tunstall and as I was walking to Tunstall I saw signposts for Blaxhall. I’d never known where Blaxhall was. It was so small it didn’t appear on any of the maps I had. When I saw it I thought “Bloody hell, that’s Blaxhall! That’s where those recordings were made.” I went on up to Tunstall and recorded Percy Web for an afternoon. I recorded about half-a-dozen songs off of him and then I said, “Percy, when I came up here I noticed there was a sign for Blaxhall”. I said “Have you ever sung in Blaxhall Ship?” He said, “Oh yes in the old days I used to sing in there quite a lot, boy”.

I said, “Do you know any of the singers there who were recorded in the ’50s?” He said, “Well I knew ‘Wicketts’ Richardson”. I thought “Bloody hell”, because he was recorded on these LPs. But he wasn’t very forthcoming. None of the singers were, really. Of course, you’d gone to see them, not to talk about anyone else!

Then I said to him, “Did you know Cyril Poacher. Is he still alive?” He said, “I don’t know boy, but I’m the only one round round here who still sings the old songs, and occasionally Bob Hart”. Well Bob Hart didn’t mean anything to me in those days, and I thought at first he was confusing him with Bob Scarce. But Bob Scarce would have been in his 90s, if he was still alive so I thought, well it wouldn’t be him. Bob Hart hadn’t become recognised as a local singer at that time. He said, “I did know Cyril but I haven’t seen him for years”. So anyway I leave Percy’s late Saturday afternoon about 5 o’clock and I was going to go back home. So I’m walking back to the station and I thought “No sod it. It’s only two miles to Blaxhall” - I didn’t mind walking in those days - I thought “I’ll go and have a look.” I wandered into Blaxhall just as 6 o’clock was coming round and opening time. There was nobody outside at all. I got in there and had a drink. I used to love a drink in those days.

I was sitting drinking and about 8 o’clock the pub starts to build up and in walks this bloke with an accordion. I’m thinking “What the ...?” Well I’d seen accordion players in Southend. One of my mate’s dads used to play the accordion - a piano accordion. But this bloke who came in had a button accordion. He starts playing and the pub starts to fill up and I’m standing at the bar talking to the barman. Somehow I got chatting with another bloke at the bar who turned out to be Fred Pearce, the melodeon player who played in Blaxhall Ship for the best part of 30 years. I knew the name because he’d been on one of the 78s I’d heard in Cecil Sharp House. I’m thinking “I don’t believe this.” I’m asking him questions and he was a bit deaf too, which meant he shouted when he replied which was just as well because it was getting noisy. I said to him, “Do they ever have singing here any more?” “Oh yeah”, he said, “but not on a Saturday night. They hold it now on a Friday night”. I said, “Well what sort of people sing? Is it the youngsters or ...?” He said, “Oh no, it’s the blokes I grew up with. Cyril Poacher, ‘Wicketts’ Richardson, Geoff Ling”. I said, “What, Cyril Poacher’s still alive?”  He said, “Yes, he’s sitting over there”. I’m sitting there thinking bloody hell and then as if that weren’t enough I then started, during a break in the music, to talk to the accordion player. I introduced myself and said, “That was great, where are you from?” He said, “I’m from Framlingham, boy”. And again the old brain goes round and I thought, Framlingham, Topic, Child ballads in England, Harry List singing the Light Dragoon. I said to him, “Have you ever heard of a bloke called Harry List?” He said, “That was my father. I’m Fred List and this is my brother Billy.” Then he started playing a step dance tune - Pigeon on the Gate. I’m sitting thinking “Jesus Christ this is all still going on.”

He said, “Yes, he’s sitting over there”. I’m sitting there thinking bloody hell and then as if that weren’t enough I then started, during a break in the music, to talk to the accordion player. I introduced myself and said, “That was great, where are you from?” He said, “I’m from Framlingham, boy”. And again the old brain goes round and I thought, Framlingham, Topic, Child ballads in England, Harry List singing the Light Dragoon. I said to him, “Have you ever heard of a bloke called Harry List?” He said, “That was my father. I’m Fred List and this is my brother Billy.” Then he started playing a step dance tune - Pigeon on the Gate. I’m sitting thinking “Jesus Christ this is all still going on.”

By then it was getting on to about 9 o’clock and I was getting a bit pissed. Because I was so shy I didn’t really go around introducing myself to everyone. I kept a very low profile. I can’t believe they forgot about me; I was so young and left-field to them, so different. They knew I was there, but everyone in the pub was perfectly alright to me. I wasn’t a collector, I didn’t make a big deal about it at all.

One of the real tips if you want to record traditional singers and musicians is to have a subject of conversation other than the music. Mine was football. I didn’t know anything about horse racing. If I had it would have been much, much better, but I did know about football and I did know about fishing. Anything like that just to change the tack so you become a little bit conversationally friendly. You’re not forever saying, “Is that a version of?”, or, “Where did you learn that?”. That can be bloody wearing on anybody, let alone somebody who’s only half interested in talking to you. So anyway I went back to the bar and got chatting with the barman, whose name was John Mitchell - a Scottish guy who was a really nice bloke. He’d been quite friendly to me when the pub was half-empty. We were chatting away and I said to him, “Is there anywhere I can stay around here?”

I had said to Fred Pearce, “You know all these other people, do they get in here regularly?” He said, “Come in tomorrow, Sunday, at 12 o’clock and I guarantee that ‘Wicketts’ and Geoff and Percy will be here. I’ll be here and Cyril” - who was playing the one-arm bandit and I didn’t dare approach - “he’ll be here and you can have a chin-wag with them then”. I thought “This is too good to an opportunity to miss”, so I phoned my parents up and said I was going to stay in Suffolk overnight and I’d come back tomorrow. So I said to John, “Is there anywhere around here I can stay, a little bed-and-breakfast or something?” “Well”, he said, “there’s the youth hostel up the road but you won’t get in there because they want a week’s notice. There’s nowhere else unless you go into Saxmundham”. That was about seven miles away. Then he said, “I run the local school bus and it’s parked out in the car-park. If you want I’ll go and open up for you and you can kip on the back seat over night”. I thought “OK, go-for-it”, it was late summer so it wouldn’t be cold. Though it was bitterly cold! I was so cold I didn’t get much sleep that night and I was well pissed. By the time I left the pub I was rocking and rolling. I slept over and woke up about seven in the morning. With five hours to kill on Sunday morning before the pub opened I wandered around the village about 20 times and eventually the local newsagents and little shop opened up. I bought the one Sunday paper they had and I must have read it from cover to cover about a dozen times.

Eventually the pub did open up at 12 o’clock. So I go in the pub and I’m sitting there and trying desperately to warm-up. John said, “Was everything alright?” I said, “Yes lovely mate”. In walks Fred Pearce again. I said, “Hello Fred”. He nodded. There was this big table, just to the left as you walked in the door, and I sat just to the right of it, hoping that they would all sit around this table if they did turn up. I didn’t expect anyone to turn up but they did. Gradually Geoff Ling came in, ‘Wicketts’ Richardson turned in, who I was gobsmacked to see. Actually he didn’t look all that old, but he was - late 70s. Cyril Poacher came in and Fred introduced me because I’d mentioned his name. Cyril was his normal self, just about managing to grunt “Hello” until he wanted to borrow two bob to play the one-arm bandit, and then he was all sweetness and light. One or two others came in. A bloke called Arthur Drewery who used to give me a lift from Wickham Market station down to the pub. That was good of him. He was a nice bloke. Gordon Keble came in and they were all sitting round this table.

Then, bugger me, in walks Bob Scarce. 88 or something, he could hardly walk, could hardly talk and plonked himself down right in the corner by the door on this big settle round this big table. I’d seen a photo of him in the Folk Song Journal. The photo had probably been taken in the fifties but you could tell immediately it was him. I turned to Fred Pearce and said, “That’s not Bob Scarce is it?” He said, “Yeah that’s Bob Scarce”. Somebody immediately sent a pint over. He was sitting there and I was thinking “God this is unbelievable!” I could not believe it. Because the recordings I’d heard of him were so individualistic and unlike you’ve ever heard any other singer in the world sing like. He sounded a very old man in the fifties. To see him in 1969 still alive was just simply unbelievable. I tried to strike up a conversation with him but it was very difficult; he was very old. But what he did say, and I’ll say this because it doesn’t really matter. I’d said to the general crowd, “You mentioned there was a film made in here?” They all said, “Oh Christ yeah”. “What a waste of time that was. Bloody hell”. The film had been made by Kennedy and Lomax. Apparently, I don’t know if this is true or not, I have no reason to doubt it, it took them 18 days to make this film during which time the pub itself had been absolutely transformed into a recording studio cum film studio. Everybody’s lives had been mercilessly disrupted. ‘Wicketts’ Richardson had cycled all round the neighbourhood to get the best singers there. Cyril Poacher sang the Nutting Girl 17 times. In fact if you ever see the film, he sings the first three verses in one jacket and the last verse in an overcoat!

I mean, don’t get me wrong, it’s a bloody good film and I don’t think it’s very far short of what was going on. It was concocted but it wasn’t a revival, it was a re-enactment of what they would normally do and they picked the best bits out of 18 different days. It’s only a 25 minute film. But during all this Geoff Ling, who was probably the best speaker of the whole lot, said, “The trouble was sonny, when Kennedy and Lomax left - they’d done this film and bollocksed our life up for the best part of three weeks - they said, ‘You lads would be the first ones to see this film when it came out’. We didn’t hear anything for six, seven, eight months maybe even longer. We started to forget all about it. We felt we’d failed, a bit like an audition”. One of the singers there, I can’t remember which one it was now, one of the singers got a letter from his daughter in Australia saying “We’ve seen your film. How wonderful it is. Lovely to see all you singers again”. He showed it to ‘Wicketts’ and all the rest of them and they went absolutely bonkers! Quite rightly so. It wasn’t six months, it was much longer, probably two or three years later. And while we’re sitting round there talking about this, little Bob Scarce, who was pushing 90 at the time, got his bony little hand, banged it on the table and the only words he uttered that made any sense. “If I see Lomax again, I’ll kill him!” This was little Bob Scarce and I’m thinking “What the ...!”

As the two-and-a-half hours of that lunchtime progressed it became apparent to me, and they said, “You want to come on Friday, mate. You don’t want to come on a Saturday, that’s when Fred List plays his melodeon”. They didn’t know that Fred knew all these songs. They knew he sang comic songs like With my Seaweed in my Hand and Somerset Fair, but they didn’t know he sang traditional songs from his father. They said, “Come on a Friday and you might hear some real singing”. Not you will hear, or we’ll put on show for you, just you might hear some real singing. So I did. I went back about three weeks later on a Friday and they had a sing-song. Cyril Poacher grudgingly sang Lamplighting Time in the Valley with his back turned to the entire audience. He sung facing the wall of the pub. I never got to the bottom of that. I think that was because there was a stranger in the midst - and that was me.

They didn’t know I was recording. I recorded surreptitiously on this Sony portable reel to reel with it under the table and the mic on the top of it. It wasn’t obvious, but anybody who saw me would have known that I was recording it. Other people were recording as well in the pub - locals. You know, middle-aged guys. There was one in particular, a man named Ken, who lived in Snape, which was just down the road. And I know that the guy who kept lovely order after ‘Wicketts’ had retired, called Clive Woolnough, who was a youngish guy, probably about 30. I know he recorded some songs in there, I know he recorded Bob Scarce. He became the chairman. After ‘Wicketts’, Clive’s dad did it for a while and then Clive did it.

If they really wanted to make a row over me recording they could have done, because they knew what I was doing. But it wasn’t that rare. I know that Neil Lanham had recorded there about seven or eight years earlier. As far as I know he was the first person to record in there since Kennedy and Lomax. I didn’t know of anybody else, which staggered me, as I assumed that this was all being documented. But it wasn’t. So I made up my mind that Sunday lunchtime. This is too good an opportunity to miss. It was all there. Cyril and others mentioned Worlingworth Swan, Snape Crown, the Plough and Sail, Eel’s Foot, Tunstall Green Man, Glemham Crown, Glemham Lion. And I’m sitting there thinking “You can’t be serious” - and they were serious. “Oh we used to sing there, and in Framlingham we used to sing at this pub - Jimmy Finbow’s”. So I decided there and then to go and record what was there. Not to document the songs and find out their provenance and their background, but to go and record the singers and musicians that were still alive.

Now coincidentally exactly at that time Topic Records, and Tony Engle in particular, who I knew from having seen him in the folk club with Oak, who I loved. That’s how I first got to know Peta and we later became partners. At that time Tony was kicking Topic off as a major label, going from issuing one traditional LP every three years to six a month. It was a phenomenal period the early seventies. And it was all fabulous stuff and coincidentally just at the time I’m getting involved in all this. Also coincidentally a girl called Ginette Dunn - who was a New Zealand girl - came over and she was at Leeds University, working with Tony Green, I believe - had been given the project of researching East Anglian traditional singing styles. She plonked herself into Blaxhall Ship probably about a year after I started. She was on ‘whatsit’ from Auckland University. She was a nice girl, Ginette. Very quiet. She was even more shy than I was. Ginette had more problems than I did because she was quite an attractive girl and some of the wives of some of the local singers started to feel a bit jealous. Even in those days - the 1970s - women in pubs were not the norm. Plus some of these singers were rather randy old men and they would chat her up something rotten. Fortunately she handled that quite well. So I carried on doing this. I had probably recorded for two years in Blaxhall Ship. I would say I went up two times every three months, on average. Loads of times I went and didn’t record. I’d got to a point where I was recording the same songs over and over again. I’d come to the bottom of the well of the local traditional singers. I’d always take the recorder with me but I didn’t often record. I was just generally treated as one of the locals. Because I had actually become not a local, but not so much of an outsider. A recognised face. They knew that I wasn’t there to rip them off.

I once asked Cyril Poacher many years later, “As you know, you’ve had your troubles in the past with people collecting. Why were you all so generous to me?” He said, “Because we felt so sorry for you boy. You didn’t have a car. You walked around. You carried all your gear with you. You weren’t a pain in the arse and we just felt sorry for you.” I thought “That’s alright.” I had proved I was not there to rip them off. If they needed an extra for the darts team I would make it up. So after about three or four months I became less of a novelty.

One of the bonuses was I could get a train from Southend on a Friday afternoon and be in Wickham Market station at half-past six. Very often this guy called Arthur Drewery - who was his early 70s. He was a local man and well liked. He’d be waiting in the car park just to see if I was on the train. He was on his way to Blaxhall Ship and if I didn’t arrive he went anyway. If I turned up with him, people who didn’t know who I was would think “He must be all right, he’s with Arthur.”

They didn’t put a show on for me, it was the same whether I was there or not. I wasn’t a major player in the evening’s events. I let them get on with it. They invited me to sing and didn’t believe it when I said I didn’t have any songs and I can’t sing. Occasionally that wasn’t good enough and they would have a bit of a pop at me. Not anything heavy. They didn’t expect me to pay for a gallon of beer or anything like that. But they did ask me to sing. On one occasion, when Jack was selling the pub, Cyril said to me, “You ought to buy this pub”, he said, “because you would keep the singing going”. Which I thought was a nice thing for him to say. I thought a lot of that.

I had three major disadvantages when I started. One was incredible shyness, secondly I had no transport and thirdly I didn’t really have a decent enough tape recorder to do it for Topic. I was gobsmacked when I found that nobody was recording it. I said, “Who is documenting all this?” They said, “What do you mean documenting?” I said, “Is anyone recording you? Is anyone taking down all these anecdotes and stories?” There may have been a local history society but living people are not the stuff of local history societies, because they can be awkward, argumentative, cantankerous. Who wants to deal with them when you can go back and refer to things that happened hundreds of years ago? I mean you look at people now in their 70s - they’re only 15 years older than I am now, but they’re not the likes of Cyril Poacher. I mean those guys were a different breed. Cyril Poacher or Charlie Whiting would argue the toss with you until the cows came home. People wouldn’t do that now. And if that didn’t work they would take you outside and give you a whack and you would expect it as well. Too bloody right. Jimmy Knights, who was five foot one and approaching 100, was not the sort of bloke you would want to get into an argument with. He wouldn’t destroy you physically but he would have you in pieces. They were lovely people but they weren’t soft. I couldn’t stand this country, cosy, village character, good old boy, what a lovely old man mentality. That held no interest for me at all. I liked the awkward difficult bastards like Cyril Poacher and Bob Scarce and several others who were ten times worse than either of them. ‘Spanker’ Austin - if you ever met him - bloody hell - fiddle player from Woodbridge. Bloody hell, the stories I could tell you about him. The sort of people they are come out in their songs and their music.

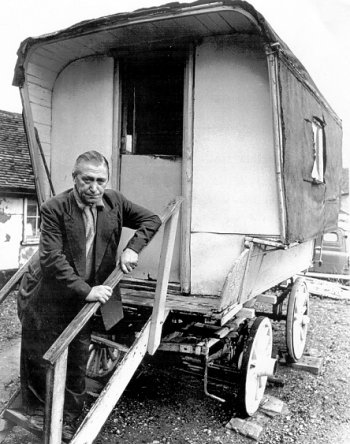

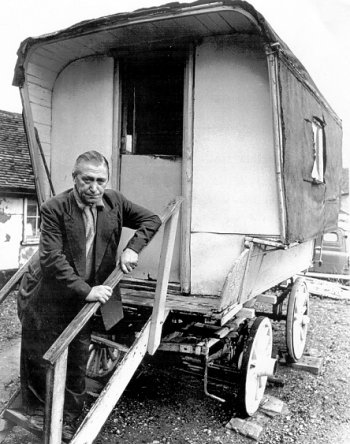

In the ’20s Blaxhall ship went through a stage where it didn’t have - this is in the late ’20s - it didn’t have a melodeon player because there wasn’t one good enough to play. So they imported from Wickham Market and Woodbridge these two fiddle players, Eley Went and ‘Spanker’ Austin - Arthur Austin - who used play together. They were both born around the turn of century so round about this time they would have been late 20s/early 30s. They cycled from where they were living. Woodbridge and Wickham Market were two towns near to Blaxhall and for some reason both of them had a tradition of string band music. They were small country towns as opposed to small villages, so they would have these dances, the Palais glide, the Lancers and the Waltz, and they would play in these string bands. They also played in the church in a quartet with another fiddle player and a cello player. They went to Blaxhall ship and they could play anything, so they played step dance music for the Smiths. They loved them, the Smiths, they loved these fiddle players. Cyril, Cyril Poacher, had managed somehow to keep in touch - and we’re talking 40 years later - with Eley Went and gave me his address in Ipswich. So I wrote to Eley Went and went round and visited him.  The most remarkable fiddle player I’ve ever heard, he really was. He’d played in dance bands. He was a bit like Walter Bulwer, he could do all of that. He knew where the notes were. He died unfortunately just after I went to see him - my one and only recording session - but he said to me, “Oh yeah I used to go around with ‘Spanker’ and we’d go to this and that and we’d go to Blaxhall Ship.” I said, “Would ‘Spanker’ Austin still be alive?” He said, “He is boy. He lives in a caravan in the car park of Woodbridge railway station.”

The most remarkable fiddle player I’ve ever heard, he really was. He’d played in dance bands. He was a bit like Walter Bulwer, he could do all of that. He knew where the notes were. He died unfortunately just after I went to see him - my one and only recording session - but he said to me, “Oh yeah I used to go around with ‘Spanker’ and we’d go to this and that and we’d go to Blaxhall Ship.” I said, “Would ‘Spanker’ Austin still be alive?” He said, “He is boy. He lives in a caravan in the car park of Woodbridge railway station.”

Now I must have seen that caravan a hundred times from the train as I went up, so I thought “Great.” A couple of weeks later I went down to Woodbridge and went to the caravan, but he wasn’t there. It was afternoon and I waited for the pub opposite to open up. I wandered in there to have a couple of beers and I went up to the bar and said to the landlady, “Have you ever heard of a bloke round here called ‘Spanker’ Austin?” She said, “About time too! About bloody time and all!” There’s me thinking “They know this guy, he’s a genius and at last somebody’s come round to record him.” “Look, look” she said, “look up in the ceiling.” So I looked up and there was this bloody great hole. I said, “What’s that?” She said, “Well that’s where he came in the other night with a double-barrelled shotgun, fired it into the ceiling, and walked out again.” She said, “You are the police aren’t you?” I said, “No.” She said, “Because we phoned the police and they said they’d send somebody round. This was best part of a week ago. We thought you were the police.” I said, “No I just want to meet the guy and talk to him.” She said, “He lives over there in that caravan.” I said, “He’s not in there at the moment.” She said, “He’s probably either dead drunk on the floor of the caravan, underneath the caravan dead drunk, or dead drunk in another pub in Woodbridge!” She was a very, very irate landlady and I left it at that. I later went back one Saturday afternoon and recorded him. He still had his little old violin under the bed. He hadn’t played for years and years. He was very pleased I was interested, but he was hard work because he was old and he’d lived a very, very rough life. There really wasn’t room for two of us and a tape recorder in his van. He was something else. There were countless stories about him. Legendary stories about him and Jimmy Knights, people like that.

So anyway in 1974, I’m pretty sure it was ’74, I was talking to Tony Engle saying, “This was all wonderful stuff”. He’d just put out the Bob Cann and the East Anglian country music one with Oscar Woods on it. Now I didn’t know Oscar Woods at that time, until the record came out. I knew him very well after that. This was all happening in very short space of time. So round about this time I said to Tony, “By the way, you’re doing all this wonderful stuff. Have you ever heard of Cyril Poacher?” He said, “Of course I have. He’s on the Folksongs of Britain Topic series”. I said, “You know he’s still alive and singing?” He said, “No”. I said, “Yes, I know him quite well”. He said, “Well can you set up a recording date and I will come up and record him”. So I did. He and Peta came up one Sunday morning. I met them at Ipswich station and they drove up to Cyril’s farm cottage in Blaxhall. I’d organised it all with Cyril and we recorded about 12 songs. Then we went back two or three weeks later and recorded another five or six to make up an LP. That was The Broomfield Wager. Tony did the bulk of the recording; I didn’t have the equipment. He did it all professionally. Cyril handled it perfectly well. He was a real professional, Cyril. Of course, they don’t take up singing and learning old songs to keep them secret. Why would you do that? One or two might say, “I’m not so sure, no, this is my family tradition”. One or two maybe, but 98 per cent of the singers were highly delighted and would organise a session for you so that they could be recorded. Totally against the grain of what you’ve read in the past and had fed to you - that these songs had to be coaxed out of people and you had to see them a dozen times before they would sing for you. There’s me, 21 years-old with hair down to my shoulders, drinking alongside them and having a good time and not knowing jack shit about the songs they’re singing but knowing this is a good singer. So we recorded Cyril and we put the LP out a short while afterwards and that seemed to go down all right.

Then I discovered ‘Jumbo’ Brightwell in Leiston which was another major shock for me. I’d thought ‘Jumbo’ Brightwell - he must be dead years beforehand, but he was still alive. Manfred Mann took me to see him. The Manfred Mann. He used to live in Westleton, a little village about four miles from Leiston. I was hitch-hiking, trying to get back to watch Southend play on the Saturday. I had got a lift and the car radio said the game was cancelled due to waterlogged pitch. So I said to the bloke, “I don’t have to go back to Southend now. Drop us off at the next roundabout and I’ll go back to Suffolk”. The first person who picked me up was Manfred Mann. He said, “What are you doing up here?” I told him and he wasn’t interested in the slightest. I said to him, “Where are you going then?” He said, “I live in Westleton but I’m going to Leiston.” I said, “Oh Leiston. Have you ever heard of a bloke called ‘Jumbo’ Brightwell?” He said, “I don’t know if his name’s Brightwell but I know a bloke called ‘Jumbo’.” So he dropped me outside ‘Jumbo’ Brightwell’s house. I bang on the door. He invites me in and sings 10 songs for me. Outside in the garden in the shadow of Leiston gas works. The first song he sung was the False Hearted Knight and my batteries run out on the tape recorder. So I go home and replay it on Colchester railway station and it sounds like Mickey Mouse because it had warmed up a little bit. I was thinking what the bloody hell’s happened here? Then I realised the batteries had run out. So I get on the phone on the Monday to speak to Tony. “By the way,” I said, “I’ve found ‘Jumbo’ Brightwell.” He said, “You’re joking.” I said, “No.” So he said, “Well set it up and we’ll come up and see him.” So I did that. He came up and recorded, again in two sessions, he did one, then I did one on my own. Enough for an LP. Then I took a week off to go on holiday. I remember thinking “This is great.” I went to Framlingham - to the the Hare and Hounds - and I remember phoning Tony up because I’d found this old boy who sung Female Cabin Boy and another old boy who sang Caroline and her Young Sailor Bold within the space of a lunchtime drinking in this pub.

I phoned Tony up, a little bit pissed in the afternoon, and told him I’d found this bloke and that bloke. “This is all good stuff”, he said, “but I can’t keep coming up. I’ve got other things to do. But what I will do, next time you’re up in London, if you want, I will lend you a Uher tape recorder and you can go and do it yourself professionally.” My immediate reaction was “Christ I’ll never get it to work.” I’m not technical at all. I’m an accountant not a sound engineer. But he ran through it for about an hour and then he said, “What do you think of that?” I said, “I’ll give it my best shot.”

So I used to hitch-hike all round Suffolk with the Uher under my arm and a microphone stand that he gave me. To begin with just one microphone then stereo microphones. And I went and recorded all these people. The first person I recorded on it was Fred List, singing and playing the accordion. Some of the best accordion / melodeon playing I’ve ever heard. Then the next day I recorded Fred Pearce, although he had officially retired as the Blaxhall musician some seven or eight years earlier. He recorded loads of old tunes for us on the Sunday. Then I went and interviewed, with Ginette, Cyril and Geoff Ling and recorded Geoff Ling’s five songs, which were issued later. So it went on. I recorded and recorded and gradually, coming back to Blaxhall, I felt all the good songs that I would want to be captured on a disc had been recorded by me or somebody else. Cyril had a limited repertoire of about 20 songs and they had all been recorded and recorded properly by Topic. The same with Geoff Ling. I didn’t record music hall songs or parodies of songs or First World War songs. They weren’t the sort of songs they would have immediately sung for me. Geoff would have gone for one of his mother’s songs or one of his grandfather’s songs. Geoff Ling was a good example of this. Depending who was asking for the song, if it was someone like me he’d go for Died For Love or Green Bushes, but equally he was just as at home with Suvla Bay or Big Wheel, but he didn’t see those as important songs. Cyril didn’t see Running Up and Down the Stairs as important. It was just something he threw in at the right moment.

So I used to hitch-hike all round Suffolk with the Uher under my arm and a microphone stand that he gave me. To begin with just one microphone then stereo microphones. And I went and recorded all these people. The first person I recorded on it was Fred List, singing and playing the accordion. Some of the best accordion / melodeon playing I’ve ever heard. Then the next day I recorded Fred Pearce, although he had officially retired as the Blaxhall musician some seven or eight years earlier. He recorded loads of old tunes for us on the Sunday. Then I went and interviewed, with Ginette, Cyril and Geoff Ling and recorded Geoff Ling’s five songs, which were issued later. So it went on. I recorded and recorded and gradually, coming back to Blaxhall, I felt all the good songs that I would want to be captured on a disc had been recorded by me or somebody else. Cyril had a limited repertoire of about 20 songs and they had all been recorded and recorded properly by Topic. The same with Geoff Ling. I didn’t record music hall songs or parodies of songs or First World War songs. They weren’t the sort of songs they would have immediately sung for me. Geoff would have gone for one of his mother’s songs or one of his grandfather’s songs. Geoff Ling was a good example of this. Depending who was asking for the song, if it was someone like me he’d go for Died For Love or Green Bushes, but equally he was just as at home with Suvla Bay or Big Wheel, but he didn’t see those as important songs. Cyril didn’t see Running Up and Down the Stairs as important. It was just something he threw in at the right moment.

We’d recorded Cyril, Cyril Poacher. I’d recorded Geoff Ling. I didn’t record Percy Ling until much much later. I can’t remember why. I felt that I had mined all the best songs out of Blaxhall. We’d got the best of Cyril, we’d got the best of Geoff. We’d got the best of several others. The singing was starting to ... not decline; people were dying! Fred Pearce died, Bob Scarce died, I found Geoff Ling’s brother in Croydon, George Ling, and recorded all his songs. The singing wasn’t dying out so much as going down a little bit and a little bit. It wasn’t happening every Friday. The other thing was the people were being moved out of Blaxhall as they got older, to Snape. In one road in Snape, which was the next village down, lived Dick Woolnough, who was a great stepdancer and singer, Percy Ling, Bob Hart, and somebody else. All in one road in Snape.

It wasn’t sheltered accommodation but similar. Alf Richardson - ‘Wicketts’ - had moved to Aldeburgh to an old people’s residential home. So he was out of the frame. And nobody was taking these blokes’ place. So you could very often go to Blaxhall and there’d only be Cyril and Geoff in the company. Maybe Percy Ling would turn up. The Ipswich folk club would occasionally turn up. The dynamics of that were different. Some of them were alright, some were quite good. The folk people would keep it to once every two months or so. It was a special occasion. I might be wrong here but they wouldn’t just turn up as I was doing on a Friday night. If the young revivalists turned up they would normally turn up en-masse for a night’s entertainment and that’s how the locals saw it. They weren’t anti it by any means. They weren’t over excited by it, but it was keeping it going and taking a bit of pressure off them.

Then you got the situation with the drink driving regulations which were tightened up in the mid seventies. People like Fred List, who drove a considerable distance from Framlingham to Blaxhall. That’s a good 20 to 25 miles, wouldn’t risk it anymore. So you’ve lost your local musician. You got Oscar Woods who was then invited down. They were all paid. Fred Pearce stopped playing not because he wanted to stop but because he fell out with the landlord. He hadn’t done it one week and they booked somebody else, not as good as him, and paid him more. Fred found out and said, “Sod you then, I’m not playing here anymore” and didn’t. He played once in the six or seven years that I was there. He only played one tune, just to keep the game alive, really. Fred List had knocked it on the head so they eventually got Oscar Woods, who was probably the best of the whole lot.

He lived nearer in Saxmundham but he didn’t have transport. He was reliant on other people. Oscar taught me to drive. He didn’t do that so that he could help me out. He wanted a chauffeur. So I used to pick him up in Benhall where he lived, next to Saxmundham, and drive us both to the Blaxhall Ship. But I was only going up there once or twice every two months so he was reliant on other people. On more than one occasion we had to walk back from Blaxhall Ship to his house in Benhall, which was a bloody long walk - a good seven miles. I was knackered and unhappy about that on more than one occasion, because Oscar had forgotten to book a taxi. But he was a lovely man, Oscar, he was one of the sort of blokes you don’t meet everyday. There was something about him and I don’t know what it was. I’ve never seen it described properly but he was different to everybody else. He was so laid-back and such a thoroughly nice bloke. It wasn’t until I started doing these tapes and putting things together that I realised what an influence he was on me.

He lived nearer in Saxmundham but he didn’t have transport. He was reliant on other people. Oscar taught me to drive. He didn’t do that so that he could help me out. He wanted a chauffeur. So I used to pick him up in Benhall where he lived, next to Saxmundham, and drive us both to the Blaxhall Ship. But I was only going up there once or twice every two months so he was reliant on other people. On more than one occasion we had to walk back from Blaxhall Ship to his house in Benhall, which was a bloody long walk - a good seven miles. I was knackered and unhappy about that on more than one occasion, because Oscar had forgotten to book a taxi. But he was a lovely man, Oscar, he was one of the sort of blokes you don’t meet everyday. There was something about him and I don’t know what it was. I’ve never seen it described properly but he was different to everybody else. He was so laid-back and such a thoroughly nice bloke. It wasn’t until I started doing these tapes and putting things together that I realised what an influence he was on me.

He found people for me. One example is I recorded a singer called George Doy. Me and Oscar had been in the Fresh - the railway refreshment rooms in Saxmundham - which was his local really. It wasn’t really a pub so much as a converted caff. He would play in there on Saturday lunchtimes just for a tune up and one or two other people would wander in. It was a nice place because everyone knew what they were going to get. You didn’t get a lot of outsiders in either. He was playing in there one lunchtime. The pub closes at half past two and he doesn’t want to go back home because by the time he’s got back home - I didn’t have my car with me - it’s time to come out again. First we went to the cafe over the road and had a little meal there. Then we went to the bookies and spent an hour in there. We still had an hour and a half to waste before the pub opened again. So he’s scratching his head in the bookies, and that’s about to close because the last race is at four. He looks at me and says, “You do know George Doy, don’t you boy? George Doy who used to sing in the Eel’s Foot.” I said, “No I have never heard the name.” Now I’d known Oscar for about four years by then and he said, “Oh. Well let’s go round and see him.”

So we trundle about a quarter mile up a road in Saxmundham, Saturday afternoon, and knock on this bloke’s door. His daughter answers the door, she’s probably in her late 40s/early 50s, and Oscar says, “Hello Marge, how’s tricks?” She says, “Hello Oscar, what do you want?” He says, “Let me just introduce this dear boy here, he’s Keith Summers, he’s recording old songs. How about George, would he like to record some old songs?” “Oh he’d love to, dear boy. All he’s doing is sitting and watching telly. He’d love to talk about the old days.” So we both wander in to his living room. I set up the recorder and his daughter gives him this great big spiel, you know, big build up. “This is my dad. He used to sing in Eel’s Foot Inn in the ’50s and in the ’40s. He knows a hundred old songs.” She went on and on and on. Then she said, “Right, over to you Dad.” And he sat there for what seemed like half an hour in total quiet, but was probably about three or four minutes. Me and Oscar were getting more and more ... we didn’t know what to do or say, and his daughter was looking embarrassed. He was just sitting there and then he starts, “It’s of a rich merchant in London did dwell.” and we all went “Phew!” It was lovely. He sang two songs, the Dark Eyed Sailor and Flower of London. Both Eel’s Foot songs. He was well into his 90s, so we didn’t press him. By which time it was time to go back to the pub. So we did. We went back to the pub. He’d done his bit, he was over the moon. I got the two recordings and they’re very good. I’m going to include one of them, the Flower of London, on this double CD.

But coming back to Oscar. Oscar was very helpful in a lot of things, which I didn’t realise at the time. If I’d made enemies. Made an enemy of Oscar - although it was almost impossible to do it - or Cyril, I’d have got nowhere, sharp! The only reason that I got recordings of Charlie Whiting in the event was Fred List gave him a right bollocking, a few days after Charlie had given me hard time in the pub. He later told me, Fred List, that the whole village, the whole pub, thought that was very poor of Charlie and well out of order and they told him so. So suddenly Charlie becomes my top man. He didn’t want to upset me or the rest of the village.

So pretty well that’s it. I kept that going up until about 1978 when I got this job in Fermanagh. In 1980 I started going out with Peta. The time wasn’t there and the singers had all died. It wasn’t the same when I came back from Ireland and I probably did my last recording in Suffolk in about 1979.

The following is taken from Earl Soham Slog LP sleeve, written in 1978, and also in Keith’s own words:

The traditional folk music of East Suffolk has probably been the best documented regional style in England over the past thirty years. Whereas much of the music and singing recorded in this period would appear to be indigenous to a general ‘East Anglian style’, it is possible, even within such a relatively small area, to detect various distinctive traditions - often revolving around either a particular pub, village or influential musician. Basically during this period, there were four such quite separate local groupings in this area, with of course some interaction between them (primarily in the case of the travelling pub musician). The best known of these was undoubtedly that centred around the singing pubs along the Aldeburgh coastal district, such as Blaxhall ‘Ship’ and the ‘Eel’s Foot Inn’ at Eastbridge. Here the music and singing was highly organised, generally as a Saturday night’s entertainment with chairmen introducing the singers and maintaining order. Secondly, the nearby towns of Woodbridge and Wickham Market boasted a fair number of dance and string bands led by men such as Walter Clow, Fred Went, Billy Hall and Lennie Pearce. A third tradition was active around the pubs in Halesworth and Yoxford area, revolving around the charismatic Seaman Family from Darsham. Finally, the small villages between Framlingham and Debenham sported a great musical tradition dominated by melodeon players Walter Read and Alf Peachey and fiddlers Walter Guyford and Harkie Nesling.

Postscript

Musical Traditions Internet Magazine republished Keith’s Sing, Say or Pay! article in 1999. You can read all the people from these CDs (plus a great many more) talking about the singing and music traditions in the East Suffolk area. It’s all there at: www.mustrad.org.uk/ssp/ssp_ndx.htm

At the time of republishing, we asked him to update it where necessary and add a new Introduction. He also added a postscript - which concluded as follows:

I must be honest and admit that it is at least ten years since I last read this article and and I don't mind telling you that I have thoroughly enjoyed reading it again. A great many happy memories and not a few profound disappointments have been relived. But the over-riding emotion is one of great good fortune to have met, in such a short period, so many thoroughly genuine, fascinating and talented people. Whether it was men with a knowledge of their tradition far beyond their immediate community like Cyril and Jumbo, well-travelled and fantastic raconteurs like Harkie, Pip or Geoff Ling, in the genial good company of Dolly or Oscar, or in the proud families of Seamo, Peachey or Walter Read, or simply an elderly woman with a shopping bag who just wandered into a pub for a sit-down while waiting for a bus and enthralled me with stories of Walter Clow and Billy Hall - they all had a story to tell. I would like to think that I did my best to tell it.

Alec Bloomfield came from a singing family; his cousin was Fred List and his father, George Bloomfield, was the source of many of his songs. Alec lived in Westleton, then Benhall and then moved away to Nottingham, which is where Keith recorded him. He was a tall man who despite working as a gamekeeper was extremely popular: “Not many poached on me those days 'cos I used to go out netting rabbits with the fishing lads when the herrings weren't coming in - but no-one ever touched my pheasants, even when times were really hard.”

Alec became a favourite singer at the famous singing pub the Eel's Foot at Eastbridge, along with chairman Philip Lumpkin, the Brightwells and the Cooks. In 1939 he was recorded by the BBC and in the 1950s Peter Kennedy recorded both Alec and his father George again for the BBC. In fact, because of Alec’s vast knowledge of local singing pubs and the singers that visited them, he became a scout for Kennedy, and it was Alec who took him for the first time to Blaxhall Ship.

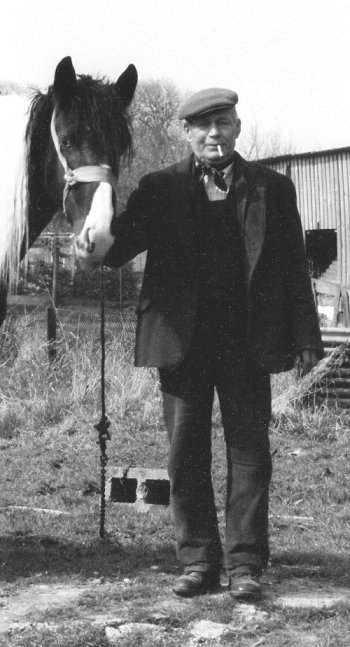

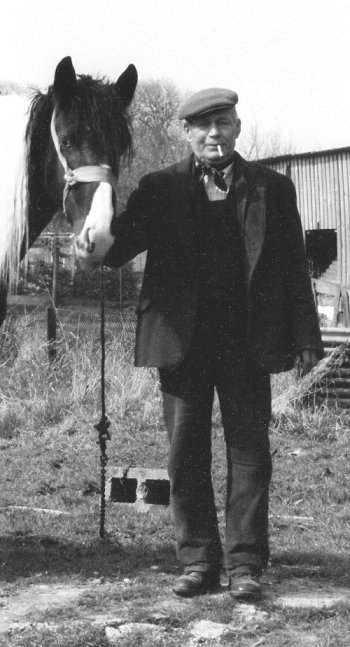

William 'Jumbo' Brightwell was born in 1900 in Little Glemham, one of eleven children. It was there he met an old sailor called Jumbo Poacher from whom he got his nickname. His first job was as a bird scarer, then after the First World War he returned to Leiston where he worked as a bricklayer's labourer, and then started at Garrett's engineering works where he served twenty years as a shunter, like his father, before retirement.

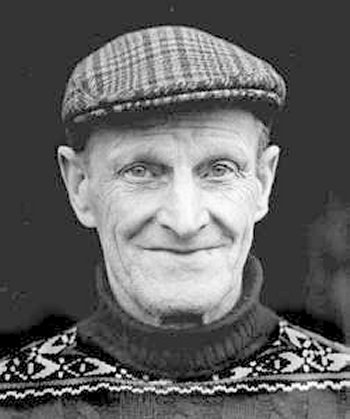

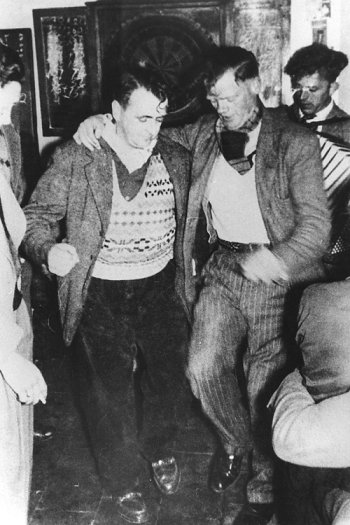

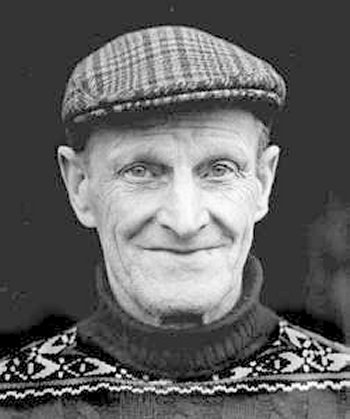

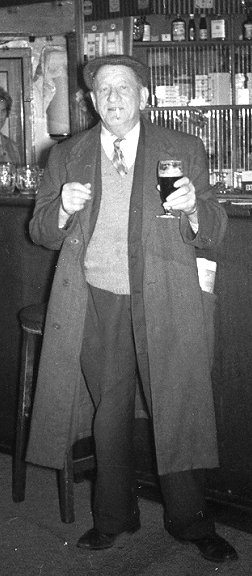

Ted Cobbin was born in 1906 in Parham but spent most of his life in Great Glemham. The family originally lived at the timber yard which was opposite the village pub, the Crown. Ted's working life was spent as a general stockman on Lord Cranbrooke's estate at Great Glemham where he tended the pigs, cows and sheep. Then in later years he looked after the horses, a job he continued with even after retirement. He was thought of very highly on the estate and when he died in 1975 they named a barn - Cobbin's Barn' - after him.

Ted Cobbin played melodeon with Peter Plant in Great Glemham Crown and sang several songs, sometimes accompanied by Peter. He rarely played anywhere else.

Cecil Fisk was born in 1920 in Bedingfield, where his family ran a building firm. When the Second World War broke out he was not called up, as building was a reserved trade, but in 1939 he volunteered, aged 19, for military service. His army career was an eventful one which included travel to Nigeria and Sierra Leone, seeing action in Egypt. While in Libya he was captured and spent 2 years in an Italian prisoner-of-war camp before he and a friend escaped, crossing the Alps into Switzerland.

Locally, Cecil was best known for playing the drums, which accounts for his strict timing with a dancing doll. He mostly played in Southolt Plough with piano player Eddie Stevenson, but also played in Brundish Crown, Dennington Bell and Worlingworth Swan with other local musicians.

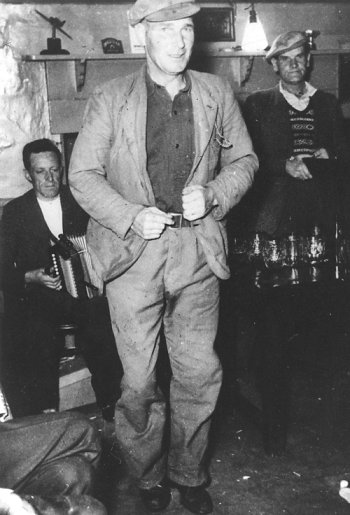

Jimmy Knights was born in 1880 in the same house in Debach where his father and grandfather had been born. When the First World War erupted he spent four years in France. Returning unscathed, he travelled the country, particularly Scotland and Yorkshire, as a stallion leader, a job he did for twenty years.

Jimmy played a banjo which he had bought in Hull during his travels. He had learned to play fiddle a bit as a boy and then found he could knock out local tunes he knew on the banjo, like Jack's the Lad, Devil and the Tailors, but it was his songs he was best known for. He sang in many of his local pubs like Bredfield Castle, Clopton Crown, Charsfield Horseshoes and Hasketon Turkey (Turk's Head) and said that he had first visited a pub when he was ten. He met and heard a lot of the older singers and it was from them he gathered his large and unusual repertoire of songs: “Well, every bugger used to sing those round here - I used to, but I prefer to sing something different - something people haven't heard before.”

Geoff Ling was born in 1916 into one of the best known singing families in Blaxhall. His grandfather Aaron, mother Susan and father Oscar were singers and his older brother, George became known as 'a rare old singer'. Geoff's dad worked at Stone Farm as a horseman where Geoff worked alongside him for some time before working on other local farms. During the Second World War he served in the army and spent several years in a Japanese prisoner-of-war-camp.

It is sad to say that over the years the number of songs available for Geoff to sing has steadily increased, as the old singers died and he became the last carrier of Blaxhall's singing tradition. He now lives in retirement in Saxmundham.

George Ling who was known as ‘Spider’ was born in Blaxhall in 1904 and was the elder brother of Geoff Ling. His grandfather Aaron, mother Susan and father Oscar were singers and everyone in the family had a go at stepping.

George's first job was with his mother stone-picking in the fields, then at twelve he went to work with a dairy herd, then went to work at Snape mailings, where he did a bricklaying apprenticeship, with singer Bob Hart as his labourer.

He moved to Croydon in 1926, and did play melodeon and sing in some of the back street pubs, although when he returned to Blaxhall on holiday he still took his place as one of the senior singers there, always remembering his early days.

Percy Ling moved to Snape in about 1930. He came from Tunstall originally, but moved when he got a job at the Maltings. Bob Hart would be on the barge weighing the malt and Percy would carry it up to the truck. “We used to do a lot of singing in Snape - all those pubs - the Key, the Crown and the Plough and Sail, and the Blaxhall crowd came down the lot. That's where you'd learn your songs, and I knew some from my grandfather, Cronie Ling. Some nights we'd get in Iken Hut, about 70 of us, and the gypsy boys would take turns serving behind a little bar. Sometimes the policeman would come in about two in the morning. Well, if he saw a pint he'd have it - they didn't mind.

Oh, we used to go anywhere for a song. Often a gang of us would cycle to Framlingham just for a night out. That's all we had then - no radio or TV. Sometimes my wife would come - she played the accordeon lovely. Now all they seem to want to hear is country and western - both my boys play that in the pubs. One Saturday night we got a bus from Tunstall to Snape - they had a fair here and they had contest, singing for a copper kettle. I sang Group of Young Squaddies. Well, I tied with another chap - they went by the crowd and we had to sing again; so I gave them Little Sweetheart in the Spring - I got it!”

Billy List (William Pearl List) was born at World's End Farm, Saxtead, in 1909 and was brother to singer and melodeon player Fred List and son of singer Harry List. Billy lived in Brundish and was remembered well by Charlie Whiting's nephew, Lenny Whiting: “Billy was a universal chap; he drove a steam engine, a steam road roller, and he drove one of those big old chain bucket cranes. He'd work round here or he'd have to go away to work for maybe two or three months and he'd work a sugar beet team. My old man and me used to meet up with Billy and his lad and we'd go rabbiting, that was when the hedges were twenty foot wide. That was Saturday and Sunday regular - well it was bit of extra spending money. They'd take them to the pub at night and raffle them off. I did hear him sing, but not a lot, because he was a Blaxhall Ship man - well in the later part of the time - because Fred List played accordeon there.”

Fred List (Frederick John List) was born at World's End Farm, Saxtead, in 1911 and was brother to Billy List. He sang lots of songs with many coming from his father, Harry List, who was recorded by Peter Kennedy for the BBC in 1951.

He learned to play melodeon as a young teenager, teamed up with George Scott, and started playing around the pubs - Framlingham Railway was their regular Saturday night spot. In later days Fred became the house musician at Blaxhall Ship and was featured on the 1974 Transatlantic LP The Larks they Sang Melodious. Fred died in 1994.

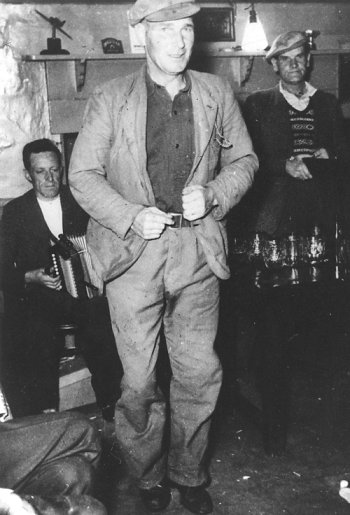

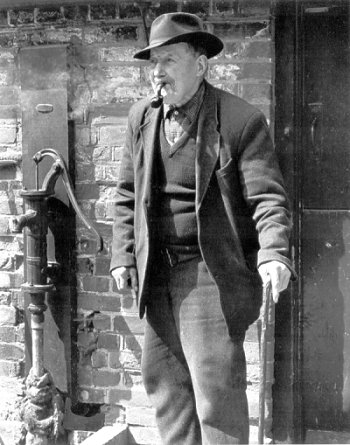

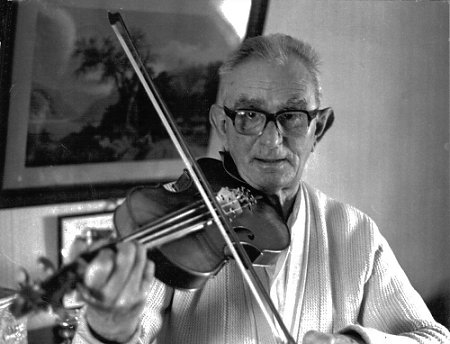

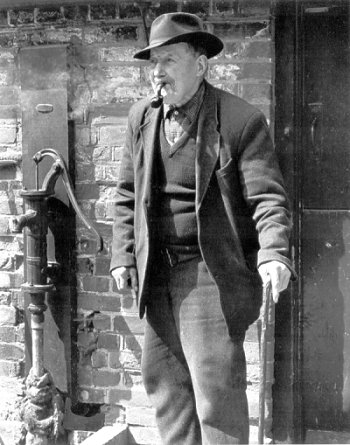

Harkie Nesling (Harcourt Nesling) was born in 1890 in Bedfield although his father's family were from Westleton. In 1910 Harkie moved to London for a short period to work as a wheelwright, and at night played in a pit orchestra for the silent movies, before an accident at work forced him to move back to Suffolk, where he married.

His first instrument was a concertina, then a 5-string banjo and a mandolin. He didn't get on the violin ‘til he was about 14. After the Great War, Harkie reunited with fiddle player Walter Gyford and melodeon player Walter Read to form a country dance band. They played for weddings and village hops, in pubs such as Monk Soham Elm and Bedfield Crown, and rather intriguingly played every Thursday (pension day) at Bedfield Post Office.

In later years Harkie teamed up with fellow fiddle enthusiast Fred Whiting, and Harkie died in 1978. As Keith summed him up: ‘Wheelwright, barber, carpenter, wart-charmer and local musician all his life!’

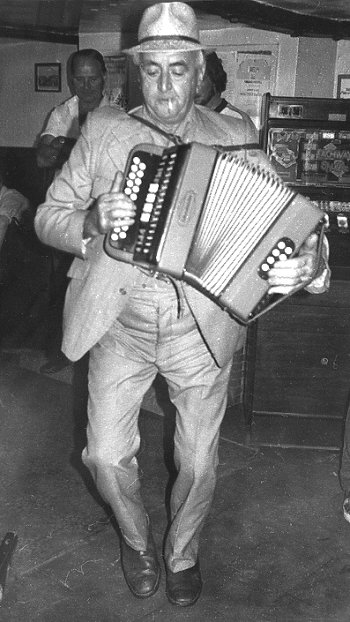

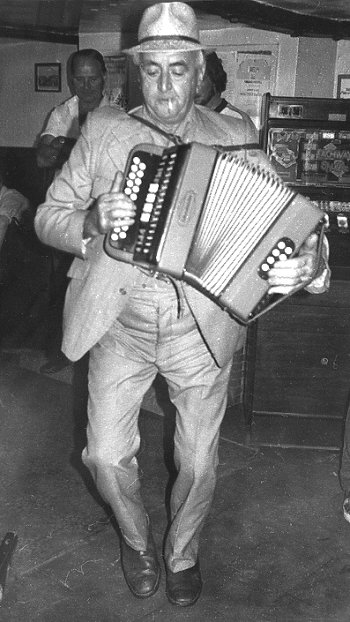

Fred Pearce was born in Eyke in 1912, and didn't move to Blaxhall till 1938. He didn't start on the accordeon ‘til he was 24, though he played mouthorgan as a child. “No-one taught me - I just picked it up.”

There were several good accordeon players at Blaxhall, but as time went on Fred established himself as the regular musician in The Ship, playing for singing (his repertoire included many traditional songs), stepping and polkas, known locally as “froggin’ rounds”.

Cyril Poacher was born at Stone Common, near Blaxhall, Suffolk, in 1910, to Alice (née Ling) and Lewis Poacher of Blaxhall. Like his father, he was a cowman almost all his life. He married, joined the army and was stationed at Catterick Camp during Second World War, before returning to Blaxhall in 1946, to work at Grove Farm, where he remained until he retired in 1975. In the early ‘70s, he moved to live in nearby Snape with his wife.

He learned songs as a child by listening to his grandfather, William ‘Cronie’ Ling, and his grandfather’s brothers, Aaron and Aldeman, and he began singing at eight years old. He first sang in public in Blaxhall Ship at the age of about nineteen. He also learned songs from other local singers there, many being of his father’s and grandfather’s generations.

Reg Reeder’s dulcimer has been in the family for about 100 years. A Mr Howard from Halesworth made it and Reg’s grandfather told him that Howard claimed to be the world champion dulcimer player.

His great-grandfather James Philpott he had a larger one, but he played a lot for parties and so he decided to get a smaller one, so it wouldn't be such a job carting it round. He swapped his with Mr Howard for this smaller one and a pair of boots. Grandfather Charlie Philpott told Reg that he first started to learn to play from his father when he was three: “He was an only child so I supposed he got a lot of attention, and he was left-handed which maybe helped him to rattle the tunes out because, my God, he did rattle them out.”

Bob Scarce (Alex Scarce) was born on 8 June 1885 in Blaxhall but lived for 25 years in Snape between the War years. Until his death in 1974 he was the oldest man living in Blaxhall who had been born there.

Although Keith Summers had met and spoken to Bob on his first night in The Ship, it was to be several months and three or four more visits before he heard him sing. He considered Bob Scarce to have been one of England's greatest traditional singers. His style was hugely idiosyncratic, immediately recognisable, and yet firmly within the declamatory Blaxhall tradition, and he had a repertoire of magnificent songs and striking ballads.

Albert Smith was born in Butley in 1914 He was a forestry worker and when he married he moved to Chillesford and lived there until he died in 1982. His cottage was small but had a large kitchen garden of which he was very proud. He was said to have fed the whole village with vegetables.

Albert's local pub was the Butley Oyster where singers like Ciss Ellis, Crump Snowden and Percy Webb sang regularly. He played mouthorgan and Jews harp as well as reciting comic 'ditties' to amuse the crowd and was often called upon to play Pigeon on the Gate for stepdancing.

Font Watling (Walter Whatling) was born in 1919 in the village where he lived all his life, Worlingworth. He worked as a driver and was one of the first in the area to have a car. Font was a true countryman and was an active member of the Dennington Pony and Trap Club, taking a cup at the Suffolk Show in 1974.

His first instrument was the concertina and he also liked to play the drums, but it was the melodeon that he became known for. His interest was first aroused when he first met Walter Read, the blind shoemaker from Bedfield, who was probably the best melodeon player in the locality. Font would take Walter in his car to remote rural pubs where they would play together.

Font's prowess as a stepdancer was well known and he won competions at Ubbeston Wheatsheaf and Badingham Bowling Green. His party piece was to step and play at the same time, which always brought the house down. One of his life-long friends was Wattie Wright with whom he would step in unision, arm in arm. In the 1950s Font formed a band with Wattie on drums and Eddie Woolnough on second melodeon.

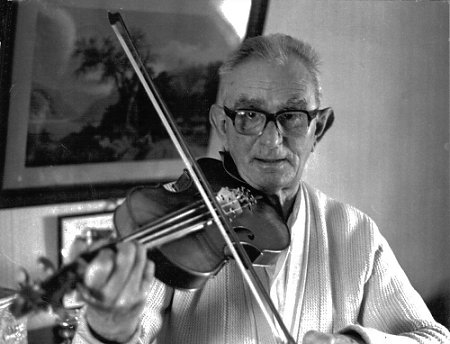

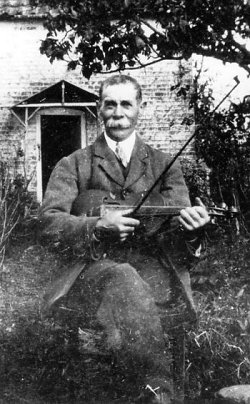

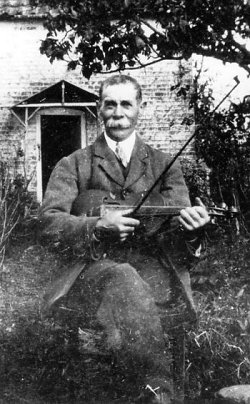

Fred Eley Went (Eley Frederick William Went) was born in Ipswich in 1900, but the family moved to Ufford when Fred was seven. He was a self-taught fiddler, although he did take lessons from a violinist from St Audrey's Hospital in Melton which gave him the rudiments of music, but as these recordings show that didn't stop him becoming a remarkably creative fiddle player.

In 1917 he went into the army and kept up his musical life by playing in a fife and drum band. After seeing action in France he returned home and started playing in local pubs, like Wickham Market Vine and Volunteer, Blaxhall Ship, Snape Plough, Easton White Horse and Woodbndge Cherry Tree. This was usually with a group of mates, particularly fiddler Spanker Austin and melodeon player Reuben Kerridge. They also played for servants' balls and in church. Around the Hacheston area he teamed up with another fiddle player, blacksmith Walter Clow, sometimes with Fred playing banjo and mouthorgan together.

In his later days he played regularly in Bramford Cock alongside musicians like David Nuttall who always remembered him being known as ‘Fiddler’ Went and there doing what he did best - improvising.

Eley Went died suddenly in 1976 but is still well remembered around Woodbridge and Blaxhall. As many people still say, “Eley Went and thar he goo”.

Charlie Whiting was born in 1905 in quite a grand farmhouse called The Homestead in Southolt, which was owned by his father, James Whiting, who was known as 'Dimmer'. When his father died, Charlie sold it and bought a little cottage on the green at Southolt opposite the Plough, where he lived until his death in 1984.

Charlie worked for his brother Jim, who had a two-horse farm called Trust Farm in Wilby. His brother spent his days out dealing with his horse and cart, while Charlie did the drilling and ploughing with the horses and looked after the few cattle and bullocks they had. In the 1950s he bought a paper round and ran this for 10 to 15 years. On retirement he did odd jobs, dug graves in Southolt church yard and was churchwarden there.

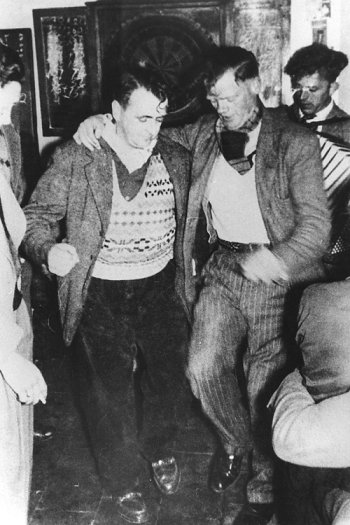

The Whiting family loved to perform (Charlie and Fred Whiting’s grandfathers were brothers). Charlie's brother Tony was known as a brilliant singer and Charlie himself was a good melodeon player until he lost some fingers in an accident. Southolt Plough was a lively pub, with people coming for miles on a Saturday and Charlie would have been amongst them all night, singing and telling tales, just as he did in Dennington Bell and Brundish Crown. But it was stepdancing that the Whitings became best known for and Charlie won competitions held at Ubbeston Wheatsheaf and at Badingham on the back of a wagon.

Charlie was such a lively character that he was given one of the main roles in 1974 film Akenfield.

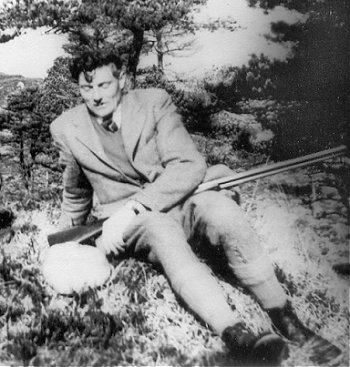

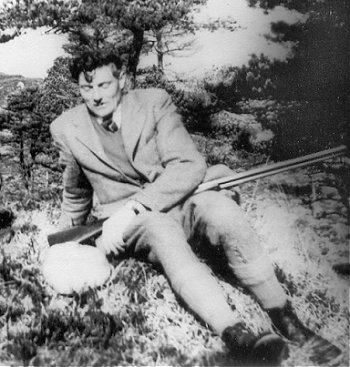

Fred ‘Pip’ Whiting was born in Kenton near Debenham in 1905 and lived there for most of his life. His father John wasn't a musician but he knew a lot of songs, and it was he taught Fred his first song.

Fred found it increasingly difficult to find work locally as a drover of sheep and in his late teens he decided to look for work in Australia and South Africa. He was also a prolific song collector, and over the years he picked up songs and tunes wherever he went.

Fred found it increasingly difficult to find work locally as a drover of sheep and in his late teens he decided to look for work in Australia and South Africa. He was also a prolific song collector, and over the years he picked up songs and tunes wherever he went.

Fred was not only an extraordinary singer, he also played fiddle left-handed. He actually had it strung normally, so he played it upside down. He also made and played dancing dolls which always pleased the gathering. After his youthful travels he returned to Kenton, the village of his birth, where he died in 1988.

Oscar Woods was born in Friston, but when he was five the family moved to Sternfield, just outside Saxmundham. Just around the corner lived an old farm worker called Tiger Smith and in the summer evenings he often played an old wind-up gramophone in his back yard, or else he played a little button melodeon. The sound of that little thing fascinated young Oscar, who used to go and sit beside him and listen.

After a while he suggested that he get one and learn to play. Eventually his dad came home with an old one with a key missing - Oc patched it up, but couldn't get on too well until he managed to buy Tiger's old two-stop. He'd concentrate on Tiger's tunes which were mainly hornpipes and country tunes, but said he found it very hard to get on with stepdance tunes and jigs.

Some time after Tiger Smith died, Oc met up with two of the Seamans from Darsham - Ernie and Charlie. Tiger had often talked of them because at one time they used to live in the same village. Oc thought that Charlie was the best player he’d ever heard, although by that time he was nearly 80 and a bit reluctant to have a go. Ernie had spent some time on the trawlers and was a bit wild, but really went to town whenever he played, and it was from them that Oc learnt a lot of their special tunes. He’d always looked forward to the time when Ernie retired so that they could get together more, but unfortunately he died suddenly just before that time, and Oc decided then that he'd try and keep their tunes going.

Subsequently Oscar and his wife moved to Benhall, not far away.

Roud numbers quoted are from the databases, The Folk Song Index and The Broadside Index, continually updated, compiled by Steve Roud. Currently containing over 270,000 records between them, they are described by him as ‘extensive, but not yet exhaustive’. Copies are held at: The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, London (where they are also available on-line); Taisce Ceol Duchais Eireann, Dublin; and the School of Scottish Studies, Edinburgh. They can also be purchased direct from Steve at Southwood, Maresfield Court, High Street, Maresfield, East Sussex, TN22 2EH, UK. E-mail: sroud@btinternet.com

Child numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child, Boston, 1882-98. Laws numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in American Balladry from British Broadsides by G Malcolm Laws Jr, Philadelphia, 1957.

CD1:

1 - 1 Doing My Duty (Roud 21227)

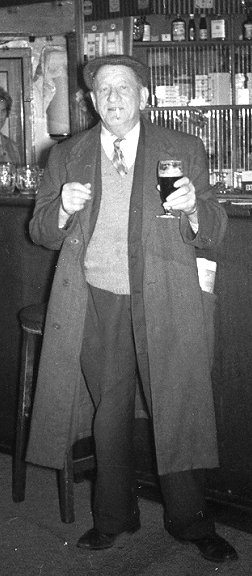

Ted Cobbin: The Crown, Great Glemham 1975

This is Ted Cobbin. The old song I'm going to sing is one I learnt from my cousin, Ross Egan. He learned it from an old pal of his right back in the Boer War, when he was a youngster with the RAMC. And I learned it from him a'singing that in the Crown here - Great Glemham. So I will do my best now. I've got a bit of a cold but I'll try my best to do it.

Now can England be in danger,

Now can England be in danger,

Is there any chance of war?

You talk about your fighting men

And your Quifer (?) gunner corps.

You talk about your Wellingtons

That fought at Waterloo,

But how about your humble

On the field of Pinky-Poo?

Yes. I was doing my duty. A doing my duty.

When the bullets were flying as thick as the mud.

I was shedding my drops of blood,

Fighting with the corporal in the ammunition van.

Yes, I was doing my duty like a soldier and a man.

Now you think when under canvas

What a pleasant time was spent,

Especially when there's fifty of you

Bunged into a tent.

There's a dozen pairs of Bluchers1,

Laying all around.

But what a rush for Keatings2

When the enemy he is found.

Yes. I'll be doing my duty. A doing my duty.

Soon as ever a flea pop out his head.

I'd give him a bash with a loaf of bread.

And then the blooming tent was like the battle of Sudan

For I was doing my duty like a soldier and a man.

Now every Sunday night when I go out,

With my best tunic dress,

A tuppeny cigar is in my mouth

And a loaf stuck up my chest.

I'm chasing bits of calico as soon as it get dark

But I've always got my eye upon the benches in the park.

Yes. I'll be doing my duty. A doing my duty.

A swinging my regimental stick,

Making myself look a bit thick,