Article MT325.

Note: place cursor on red asterisks for footnotes.

Thomas Ravenscroft and The Three Ravens

A Ballad Under the Microscope

by Arthur Knevett

Introduction

The version of The Three Ravens in Frank Kidson's collection Traditional Tunes: A Collection of Ballad Airs is a ballad that has been in my repertoire for many years and was included on my 1987 cassette Mostly Ballads. When, by chance, I came across a journal article entitled 'The Three Ravens Explicated' by Vernon V Chatman III I was so surprised at the analysis put forward to show that the ballad was Irish in origin and dated back to the twelfth century that I was prompted to investigate the provenance of the ballad to determine the veracity of Chatman's analysis.

Thomas Ravenscroft's Song Books

The earliest known text and tune of The Three Ravens was included in a collection by Thomas Ravenscroft. Ravenscroft compiled three song books, Pammelia, Deuteromelia, both published in 1609, and in 1611 he published Melismata. The three books contained catches, rounds, street cries, vendor songs and other anonymous music. Z D M Bidgood described them as the '... first collections in English to include any significant material of popular or traditional origin.' 1

1

The three books are not directly attributed to Thomas Ravenscroft as the compiler or editor. Indeed the first book, Pammelia, provides no named author or compiler. However Deuteromelia and Melismata give the initials T.R. and in Melismata the 'Epistle Dedicatorie' is given to; 'Mr. Thomas Ravenscroft and Mr. William Ravenscroft Esquires' and concludes with the valediction 'Your Worships Affectionate Kinsman, T.R.'![2. Melismata: Musical Phansies Fitting the Court, Citie and Country Humours [attributed to Thomas Ravenscroft], (London: Printed by William Stansby for Thomas Adam, 1611), p.3.](../graphics/r_note.gif) 2 Bidgood attributes all three works to Thomas Ravenscroft. Melismata contains twenty three items and is divided into five sections; Court Varieties (nos 1-6), Citie Rounds (nos 7-10), Citie Conceits (nos 11-14), Country Rounds (nos 15-19) and Country Pastimes (nos 20-23). The ballad 'The Three Ravens' is no.20 in the last section.

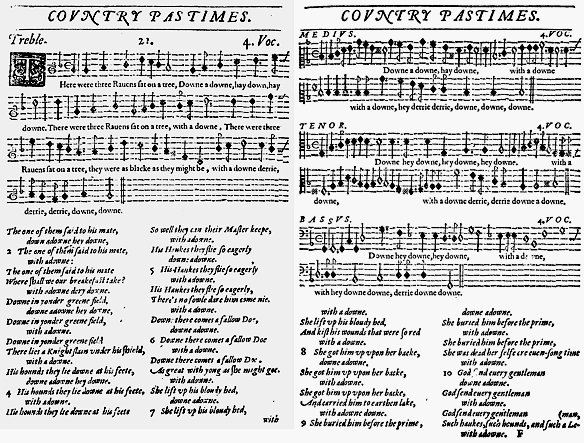

2 Bidgood attributes all three works to Thomas Ravenscroft. Melismata contains twenty three items and is divided into five sections; Court Varieties (nos 1-6), Citie Rounds (nos 7-10), Citie Conceits (nos 11-14), Country Rounds (nos 15-19) and Country Pastimes (nos 20-23). The ballad 'The Three Ravens' is no.20 in the last section.

Front cover of Thomas Ravenscroft's Melismata

In 1614 Ravenscroft published another collection with the unwieldy title of; A Briefe Discourse of the True (but neglected) use of Charact'ring the Degrees by their Perfection, Imperfection, and Diminution in Measurable Musicke against the Common Practice and Custom of these Times. Examples whereof are exprest in the Harmony of 4 Voyces, Concerning the Pleasure of 5 usuall Recreations - 1. Hunting, 2. Hawking, 3. Dauncing, 4. Drinking, 5. Enamouring. 3 The work contained twenty musical 'examples' of which Ravenscroft composed eleven. He also composed ten anthems and a motet and in 1621 he published a metrical psalter, The Whole Booke of Psalmes.

3 The work contained twenty musical 'examples' of which Ravenscroft composed eleven. He also composed ten anthems and a motet and in 1621 he published a metrical psalter, The Whole Booke of Psalmes. 4

4

The Ballad Story of 'The Three Ravens'

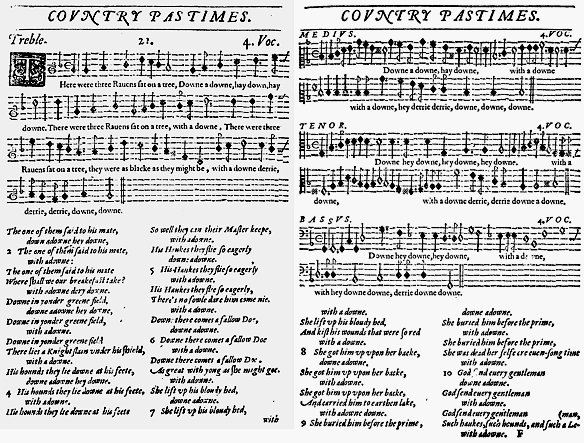

The earliest printed text and tune of The Three Ravens is to be found in Ravenscroft's Melismata. The role of the 'ravens' is to introduce the narrative, which tells how the body of a slain knight is faithfully guarded by his hounds and hawks until his lady, in the form of 'a fallow doe as great with young as she might go' can provide him with a dignified burial and having done so she then dies. Thus the ravens are deprived of their 'breakfast'.

The Three Ravens No. 20 in the section Country Pastimes

The Three Ravens has its Scottish counterpart, rather than a traditional version, in The Twa Corbies. The earliest printed text of the ballad in its Twa Corbies form was in 1803 when Walter Scott included it in his collection Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. 5 In this form the tenderness of the Ravenscroft version has given way to irony and the two crows, who replace the three ravens, are overheard to comment cynically:

5 In this form the tenderness of the Ravenscroft version has given way to irony and the two crows, who replace the three ravens, are overheard to comment cynically:

The Twa Corbies

I

As I was walking all alane,

I heard twa corbies making a mane;

The tane unto the t'other say,

Where sall we gang and dine to-day?

II

In behind yon auld fail dyke,

I wot there lies a new slain knight;

And naebody kens that he lies there,

But his hawk, his hound, and his lady fair.

III

His hound is to the hunting gane,

His hawk, to fetch the wild-fowl hame,

His lady's ta'en another mate

So we may mak our dinner sweet.

IV

Ye'll sit on his white hause-bane,

And I'll pick out his bonny blue een.

Wi' ae lock o' his gowden hair,

We'll theek our nest when it grows bare.

V

Mony a one for him makes mane,

But none sall ken whare he is gane:

O'er his white banes, when they are bare,

The wind sall blaw for evermair. 6

6

[Ibid. The Twa Corbies, pp. 417-418.]

The Ballad also migrated to America and Arthur Kyle Davis Jr writes that; 'The American texts, ... are far removed from the British versions. The change in spirit is symbolized by the change in title to "The Three Crows." The usual American text is certainly less poetical than either the English "The Three Ravens" or the Scottish "The Twa Corbies," though it is closer to the grisliness of the latter than to the tenderness of the former.' 7

7

It has even been collected as a shanty, William Main Doerflinger prints a version to the 'Blow the Man Down' tune (see below) and writes that; 'Les Nickerson, a Nova Scotian, used verses from the ancient Anglo-Scottish ballad of "The Three Crows" or "The Twa Corbies"':

Blow the Man Down (IV)

1 There were three crows sat on a tree,

Way, hay, blow the man down,

And they was as black as black could be,

Gimme some time to blow the man down!

2 Says one old crow unto his mate,

"where shall we go for something to ate [eat]?

3 "There is an old horse on yonder hill,

And there we can go and eat our fill."

4 "There is an old horse on yonder mound

,

We'll light upon to his jaw-bone."

5 Says one old crow unto the other,

"We'll pick his eyes out one by one." 8

8

[William Main Doerflinger, Shantymen and Shantyboys: Songs of the Sailor and Lumberman (Nwe York: Macmillan, 1951) p.21.]

The 'Corpus Christi' Carol

Bidgood contends that Ravenscroft was '... eminently suitable to have recorded the songs of his age for posterity'. 9 Joseph Ritson included Ravenscroft's The Three Ravens (text only) in his book Ancient Songs and Ballads, first published in 1790. He believed it to be 'much older, not only than the date of the book, [Melismata] but than most of the other pieces contained in it.'[Joseph Ritson, Ancient Songs and Ballads: From the Reign of King Henry the Second to the Revolution. Third Edition, Carefully Revised By W Carew Hazlitt (London: Reeves and Turner, 1897) pp.193-194.]

9 Joseph Ritson included Ravenscroft's The Three Ravens (text only) in his book Ancient Songs and Ballads, first published in 1790. He believed it to be 'much older, not only than the date of the book, [Melismata] but than most of the other pieces contained in it.'[Joseph Ritson, Ancient Songs and Ballads: From the Reign of King Henry the Second to the Revolution. Third Edition, Carefully Revised By W Carew Hazlitt (London: Reeves and Turner, 1897) pp.193-194.] 10 However, Ritson offers no evidence for this assertion. William Chappell also included the ballad in Old English Popular Music, he quoted Ritson's comments and in so doing he clearly agreed that the ballad was of earlier origin than the publication of Melismata.

10 However, Ritson offers no evidence for this assertion. William Chappell also included the ballad in Old English Popular Music, he quoted Ritson's comments and in so doing he clearly agreed that the ballad was of earlier origin than the publication of Melismata. 11 Chappell acknowledges that Ravenscroft's three books '... were an attempt to preserve the popular music of the preceding century' but regrets that Ravenscroft; '... gives none of that information, with respect to his material and his treatment of it, which is nowadays considered indispensable in a work of this kind.'

11 Chappell acknowledges that Ravenscroft's three books '... were an attempt to preserve the popular music of the preceding century' but regrets that Ravenscroft; '... gives none of that information, with respect to his material and his treatment of it, which is nowadays considered indispensable in a work of this kind.' 12

12

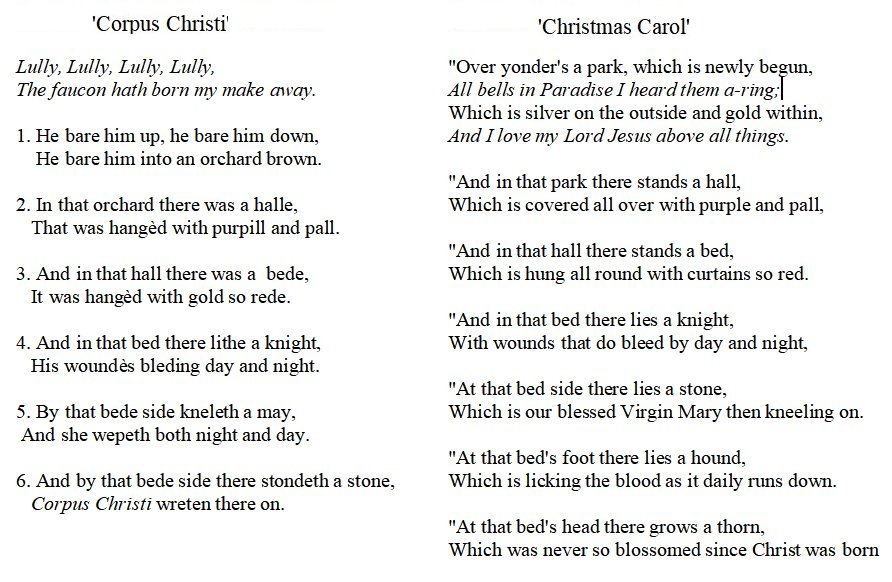

Bertrand Bronson in his notes to The Three Ravens in The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads has argued that the points of comparison between the 'Corpus Christi' carol and 'The Three Ravens' 'appear too striking to be purely accidental.' 13 He writes that:

13 He writes that:

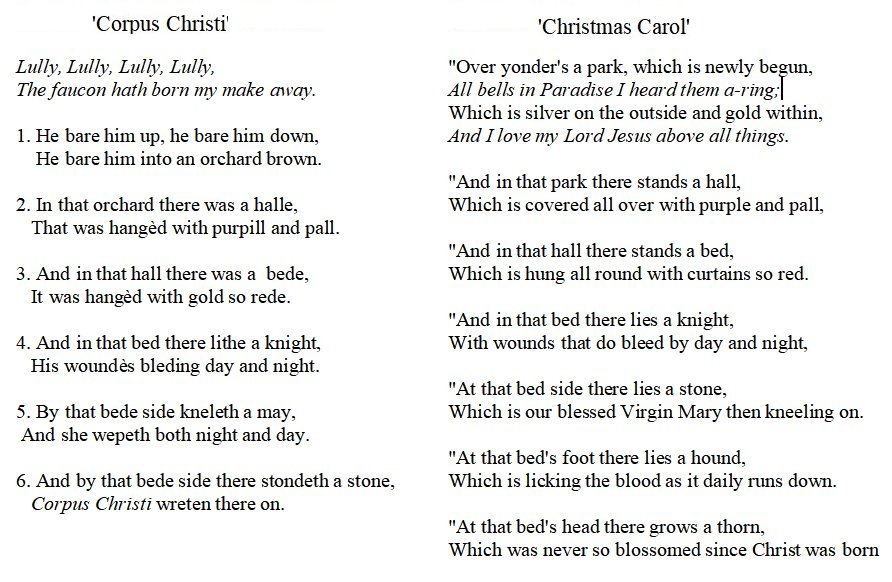

There exists a piece of collateral evidence which would move it back into the fifteenth century. That evidence is the now well known 'Corpus Christi' carol, still current, like the ballad, in oral tradition, [see Fig. 6] and of which the oldest extant text was recorded in the first part of the sixteenth century. ... For our immediate purposes it is sufficient to note general agreement that the piece is a pious adaption of an earlier secular folk song or ballad. My own persuasion is that some prior variant of 'The Three Ravens' is that very antecedent. 14

14

In comparing The Three Ravens with the 'Corpus Christi' carol Bronson is tacitly agreeing with J A Fuller Maitland who, with regard to the 'Corpus Christi' carol, proposed that; 'The presence of the 'faucon,' the wounded Knight, the weeping woman and the hound ..., suggests that in its secular form this song is nearly related to 'The Three Ravens' or 'The Twa Corbies'.'![15. J. A. F. M. [J. A. Fuller Maitland], fn. in Annie G. Gilchrist 'Over Yonder's A Park', Journal of the Folk-Song Society, 4.1 (No.14, June 1910), 52-66 (p.64).](../graphics/r_note.gif) 15

15

How old is the ballad The Three Ravens?

The 'Corpus Christi' carol, without a title, is to be found in an early 16th century MS in Balliol College Library, the MS in question being the Common-place book of Richard Hill. The carol, number eighty-one and without a title, was included in Early English Lyrics. 16 The carol with the title Corpus Christi was given as a means of reference by Frank Sidgwick and appeared with that title in Journal of the Folk-Song Society 4.1 (No. 14, June 1910, p.53. In the notes to the carol Chambers and Sidgwick state that in Richard Hill's book; '... The latest date in it is 1535, but part must have been written before 1504'.

16 The carol with the title Corpus Christi was given as a means of reference by Frank Sidgwick and appeared with that title in Journal of the Folk-Song Society 4.1 (No. 14, June 1910, p.53. In the notes to the carol Chambers and Sidgwick state that in Richard Hill's book; '... The latest date in it is 1535, but part must have been written before 1504'. 17

17

No other early version of the carol is known, but a traditional version with a different refrain was collected in North Staffordshire around the middle of the nineteenth century and contributed to Notes and Queries (1862) by a correspondent signing himself E. T. K. who stated that; 'The following Christmas Carol was sung to a wild and beautiful tune, by a boy, who came to my house as one of a company of morris-dancers during the Christmas some years ago.' 18

18

Francis James Child noted in volume 4 of the The English and Scottish Popular Ballads that a tune entitled 'Ther wer three ravens' was included in; '... a MS Lute-Book ... which contained airs 'noted and collected by Robert Gordon at Aberdeen in the year of our Lord 1627'.' 19 It is reasonable to assume that since the air was collected it must have been in circulation long enough for it to become established in the tradition. However, we do not know if it was collected as a tune or a song. Nonetheless, Child clearly deemed it to be worthy of mention. In the section 'Additions and Corrections' of volume 5 of the The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Child prints a version of The Three Ravens collected in Lincolnshire in 1793. It was collected from a farm labourer who; '... had 'learnt it 'from his fore-elders'.' In this version the 'fallow doe' is replaced by 'a lady full of woe, as big with bairn as she can go.'

19 It is reasonable to assume that since the air was collected it must have been in circulation long enough for it to become established in the tradition. However, we do not know if it was collected as a tune or a song. Nonetheless, Child clearly deemed it to be worthy of mention. In the section 'Additions and Corrections' of volume 5 of the The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Child prints a version of The Three Ravens collected in Lincolnshire in 1793. It was collected from a farm labourer who; '... had 'learnt it 'from his fore-elders'.' In this version the 'fallow doe' is replaced by 'a lady full of woe, as big with bairn as she can go.' 20 Frank Kidson collected a traditional fragment of the ballad from; '... Mr John Holmes, of Roundhay, [WestYorkshire], who first heard it about 1825 from his mother's singing. This was in a remote village among the Derbyshire hills, most aptly named Stoney Middleton.'

20 Frank Kidson collected a traditional fragment of the ballad from; '... Mr John Holmes, of Roundhay, [WestYorkshire], who first heard it about 1825 from his mother's singing. This was in a remote village among the Derbyshire hills, most aptly named Stoney Middleton.' 1

1 21 Here too the 'fallow doe' is replaced by; '... his lady full of woe, ...'.

21 Here too the 'fallow doe' is replaced by; '... his lady full of woe, ...'.

The Three Ravens

There were three ravens on a tree,

A-down, a-down, a derry down,

There were three ravens on a tree,

Heigh ho!

The middlemost raven said to me,

'There lies a dead man at yon tree'

A-down, a-down, a derry down,

Heigh ho!

There comes his lady full of woe,

A-down, a-down, a derry down,

There comes his lady full of woe,

There were three ravens on a tree,

Heigh ho!

There comes his lady full of woe,

. . . . . as she could go,

A-down, a-down, a derry down,

Heigh ho!

'Who's this that's killed my own true love,

A-down, a-down, a derry down,

Who's this that's killed my own true love,

Heigh ho!

I hope in heaven he'll never rest,

Nor e're enjoy that blessed place.'

A-down, a-down, a derry down,

Heigh ho!

Commenting on Child's Lincolnshire version of the ballad Lowry Charles Wimberley stated that:

'... the 'leman' is called 'a lady, full of woe,' but this copy is one of those 'traditional copies, differing principally by what they lack.' There can be little question that one of the things lacking here is the 'doe' form of the mistress. It is worthy of note that in a copy of The Twa Corbies, a 'cynical variation' of The Three Ravens, the knight has been hunting the 'wild deer.' It is very probable that our ballad reflects the tradition of beast marriage, a tradition preserved in popular tales the world over, tales on the order of Perrault's story of 'Beauty and the Beast' and current among civilized, barbarous and savage people.' 22

22

If, as suggested, The Three Ravens is the antecedent of the 'Corpus Christi' carol then the ballad The Three Ravens would have originated sometime before the inclusion of 'Corpus Christi' in the early sixteenth century MS.

Vernon V Chatman III's Explication

The idea of 'beast marriage' has been further developed by Vernon V Chatman III. In an article entitled 'The Three Ravens Explicated'. 23 He argues that the' fallow doe' is not an epithet for a pregnant woman since she would be unable to carry out the tasks described in the ballad, but is more likely to refer to a; '... centaur-like woman, or to coin a word a dainefemme, (deerwoman), presumably possessing nymph-like qualities'

23 He argues that the' fallow doe' is not an epithet for a pregnant woman since she would be unable to carry out the tasks described in the ballad, but is more likely to refer to a; '... centaur-like woman, or to coin a word a dainefemme, (deerwoman), presumably possessing nymph-like qualities' 24 and thus she would be able to carry out the tasks described in the ballad. Furthermore, he argues that these supernatural qualities would be recognised by the knight's hounds since '... dogs can see spirits',

24 and thus she would be able to carry out the tasks described in the ballad. Furthermore, he argues that these supernatural qualities would be recognised by the knight's hounds since '... dogs can see spirits', 25 consequently they would be subdued even though, under normal circumstances, when out hunting with their master they would give chase to a deer. Referring to the burden, or refrain, Chatman continues in the same vein and develops a theory regarding each of the refrain lines. His argument is so fanciful that it is quoted below in full, he writes:

25 consequently they would be subdued even though, under normal circumstances, when out hunting with their master they would give chase to a deer. Referring to the burden, or refrain, Chatman continues in the same vein and develops a theory regarding each of the refrain lines. His argument is so fanciful that it is quoted below in full, he writes:

Let us proceed one line at a time. We find in the Oxford Universal Dictionary (1955) that 'down' can be used as an adverb either attributively or by ellipsis of some participial word in the sense of 'dejected.'' Also, we find that 'a' can be used as a preposition as in 'a live' or as an adjective in the sense of 'all.' Further, we find that 'hay' can be used as an interjection in the sense of 'thou hast (it)' and that it occurs in the phrase 'to make hay' this phrase meaning 'to make confusion.' Thus, the sense of line two is something like the following: 1) Dejected all dejected, thou hast dejection [thou art dejected?], thou hast dejection; or 2) Dejected all dejected, confused and dejected, confused and dejected.

Relative to line four we find in the Oxford Universal Dictionary that 'with' can be used to form adverb phrases denoting 'to the fullest extent.' Thus, the sense of the fourth line is something like the following: Utterly (completely) dejected.

Checking this time with Encyclopaedia Britannica (1956) we find that Londonderry was once named 'Derry.' Derry is an appropriate locale for the scene depicted in 'The Three Ravens:' the Scandinavians plundered the city, and it is said to have been burned down at least seven times before 1200; it thus is a site of many battles. Line seven, now Line seven presents the gravest difficulty; however, it can be surmounted. The problem here centers upon 'derrie.' 'means' something like the following: Utterly dejected in Derry, in Derry, dejected, dejected.

The above renderings may at first strike one as maverick; however, their contribution to the total poem (i.e. the coherence which they establish) offers sufficient justification for their acceptance. 26

26

Chatman's analysis is problematic. In his article he has proposed a set of ideas and has then found sources which support them. In so doing he has neglected to employ an approach whereby these ideas are tested by counter-argument and then modified accordingly, consequently his ideas are unsubstantiated. Nevertheless, based on this analysis he has concluded that the ballad The Three Ravens is Irish in origin and may date back as early as the twelfth century.

An examination of Vernon V Chatman 111's analysis

With regard to Chatman's contention that the city of Derry was plundered by the Scandinavians and 'burned down at least seven times before 1200' we are told that; 'Although the Vikings certainly sailed up the loughs and rivers of this area, the monastery of Derry escaped the worst effects of their raids.'![27. Northern Irish Tourist Board, 'History of Derry', available at < www.geographia.com/northern-ireland/ukider01.htm> [accessed 25/07/2019].](../graphics/r_note.gif) 27 Also, Derry was only a small settlement, not a city. 'It did not become truly important until the 17th century.'

27 Also, Derry was only a small settlement, not a city. 'It did not become truly important until the 17th century.'![28. Tim Lambert, 'A Brief History of Derry', available at, [accessed 25/07/2019].](../graphics/r_note.gif) 28 Furthermore, I am reliably informed that the language spoken pre-Londonderry (Derry was re-named Londonderry in 1623) was Irish and that the place was called Doire, pronounced dirra, (meaning oak grove). Inishowen, just to the north had six or seven small monasteries in the seventh to twelfth centuries and only a little evidence of Viking influence has been found.

28 Furthermore, I am reliably informed that the language spoken pre-Londonderry (Derry was re-named Londonderry in 1623) was Irish and that the place was called Doire, pronounced dirra, (meaning oak grove). Inishowen, just to the north had six or seven small monasteries in the seventh to twelfth centuries and only a little evidence of Viking influence has been found. 29

29

Regarding the 'derry down' refrain, which is common to a number of songs with no more significance than a 'right fol de rol' type chorus, Chatman chooses to give it some intrinsic meaning to the ballad and he does so by making use of grammar in an inventive way. While it is true that the word 'down' can indeed mean dejected and the phrase 'to make hay of' (not 'to make hay' as Chatman has it) can mean to throw into confusion, he feels able to assert that the first part of the refrain means 'Dejected all dejected, confused and dejected, confused and dejected'. With regard to the last line of the refrain; by making Derry the subject, he is able to make use of the rules of grammar to interpret the refrain to mean 'utterly dejected in Derry, in Derry, dejected, dejected.' However, he neglects to take into account the aforementioned history of Derry which, I contend, renders his analysis untenable. Moreover, the Roud index lists two hundred and fifty four versions of 'The Three Ravens / Crows' in print and as recordings of traditional performances, a number of the print versions are duplicated appearing in different publications, and none of the versions listed are Irish. Commenting on ballads in Ireland Hugh Shields stated that; 'it is hardly surprising that the ballad genre reached Ireland through Britain ... Given moreover the special cultural characteristics of Gaelic society and its conservative attachment to native genres, it is not surprising that the ballad acquired no idiomatic Gaelic forms ...' 30 Furthermore, the Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA) has found no reference in its collections of the ballad The Three Ravens being traditionally sung in Ireland.

30 Furthermore, the Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA) has found no reference in its collections of the ballad The Three Ravens being traditionally sung in Ireland. 31

31

Conclusion

Thomas Ravenscroft's collection of catches, rounds, street cries and songs in Melismata published in 1611 provides us with the earliest known version of the ballad The Three Ravens. It is generally accepted by folk song scholars such as Bronson, Gilchrist and Fuller Maitland that the ballad is an earlier secular antecedent of the carol 'Corpus Christi' found in an early sixteenth century manuscript some of which may have been written or compiled before 1504. This suggests that The Three Ravens may well have originated sometime in the fifteenth century and was English. Vernon V Chatman's article, 'The Three Ravens Explicated', to be found in the journal Midwest Folklore, endeavours to show that the ballad was Irish in origin and dates back to the twelfth century. To do so he has used folk tales and the rules of grammar to give unfounded meaning to some of the text, particularly the refrain; consequently his argument is sheer conjecture. There is no evidence available to suggest that the ballad is Irish or has an earlier date of origin than the fifteenth century.

Arthur Knevett - 3.10.19

Notes:

1. Z.D.M. Bidgood, 'The Significance of Thomas Ravenscroft', Folk Music Journal, 4.1 (1980), 24-34 (p.24).

2. Melismata: Musical Phansies Fitting the Court, Citie and Country Humours [attributed to Thomas Ravenscroft], (London: Printed by William Stansby for Thomas Adam, 1611), p.3

3. Jeffrey Mark, 'Thomas Ravenscroft, B.Mus. (c.1583 - c.1633)', The Musical Times Vol. 65. 980 (October 1 1924), .881 - 884 (p.883).

4. Ibid. p.884.

5. Sir Walter Scott, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, 4 vols rev.and ed. by T.F.Henderson (Edingburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1932) II, pp. 415-418.

6. Ibid. The Twa Corbies, pp.417-418.

7. Arthur Kyle Davis Jr. Eed. More Traditional Ballads of Virginia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1960) p.84.

8. William Main Doerflinger, Shantymen and Shantyboys: Songs of the Sailor and Lumberman (Nwe York: Macmillan, 1951) p.21.

9. Bidgood. p. 27.

10. Joseph Ritson, Ancient Songs and Ballads: From the Reign of King Henry the Second to the Revolution. Third Edition, Carefully Revised By W. Carew Hazlitt (London: Reeves and Turner, 1897) pp.193-194.

11. William Chappell, Old English Popular Music: A New Edition With a Preface and Notes, and the Earlier Examples Entirely rev. by H. Ellis Wooldridge, (New York: Jack Brussel, 1961), xv.

12. Ibid. xv.

13. Bertrand Harris Bronson, The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads: With Their Texts, According to the Extant Records of Great Britain and America, 4 vols ( Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1959), I, p.308.

14. Ibid. p.308.

15. J. A. F. M. [J. A. Fuller Maitland], fn. in Annie G. Gilchrist 'Over Yonder's A Park', Journal of the Folk-Song Society, 4.1 (No.14, June 1910), 52-66 (p.64).

16. Ibid, p. 148. The carol with the title Corpus Christi was given as a means of reference by Frank Sidgwick and appeared with that title in Journal of the Folk-Song Society 4.1 (No. 14, June 1910), p.53.

17. Early English Lyrics: Amorous, Divine, Moral and Trivial, ed. by E. K. Chambers and F. Sidgwick, (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1926, reprint of the edition published London: Bullen, 1907), p.307.

18. E. T. K. 'Christmas Carol' in Notes and Queries: Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, Artrists, Antiquaries, Genealogists Etc Third Series-Second Volume (London: Bell and Daldy, 1862), p.103.

19. Francis James Child, 'Additions and Corrections', notes for no. 26. The Three Ravens', in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads , 5 vols, (New York: Dover Publications , 1965, unabridged reprint of the edition published by Houghton, Mifflin and Co. 1882-1898), IV, p.454.

20. Francis James Child, 'Additions and Corrections', notes for no. 26. The Three Ravens', in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads 5 vols, (New York: Dover Publications , 1965, unabridged reprint of the edition published by Houghton, Mifflin and Co. 1882-1898), V, p.212.

21. Frank Kidson, Traditional Tunes: A Collection of Ballad Airs, Chiefly Obtained in Yorkshire and the South of Scotland; Together with their Appropriate Words from Broadsides and from Oral Tradition (Oxford: Chas. Taphouse & Son, 1891) pp.17-18

22. Lowry Charles Wimberley, Folklore in the English and Scottish Ballads, (New York: Dover Publications, 1965, unabridged republication of the 1928 edition published by University of Chicago Press) pp.55-56.

23. Vernon V. Chatman, 'The Three Ravens Explicated', Midwest Folklore, 13.3 (1963), 177-186.

24. Ibid. p.177.

25. Ibid. p.177.

26. Ibid. p.178.

27. Northern Irish Tourist Board, 'History of Derry', available at < www.geographia.com/northern-ireland/ukider01.htm> [accessed 25/07/2019].

28. Tim Lambert, 'A Brief History of Derry', available at, [accessed 25/07/2019].

29. I am very grateful to John Moulden for providing this information.

30. Hugh Shields, Narrative Singing in Ireland: Lays, Ballads, Come-All-Yes and Other Songs (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1993). p.40.

31. I am grateful to Róisín Ni Bhriain and Grace Toland at the Irish Traditional Music Archive for this information.

Article MT325

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 4.10.19

![]() 2 Bidgood attributes all three works to Thomas Ravenscroft. Melismata contains twenty three items and is divided into five sections; Court Varieties (nos 1-6), Citie Rounds (nos 7-10), Citie Conceits (nos 11-14), Country Rounds (nos 15-19) and Country Pastimes (nos 20-23). The ballad 'The Three Ravens' is no.20 in the last section.

2 Bidgood attributes all three works to Thomas Ravenscroft. Melismata contains twenty three items and is divided into five sections; Court Varieties (nos 1-6), Citie Rounds (nos 7-10), Citie Conceits (nos 11-14), Country Rounds (nos 15-19) and Country Pastimes (nos 20-23). The ballad 'The Three Ravens' is no.20 in the last section.

![]() 3 The work contained twenty musical 'examples' of which Ravenscroft composed eleven. He also composed ten anthems and a motet and in 1621 he published a metrical psalter, The Whole Booke of Psalmes.

3 The work contained twenty musical 'examples' of which Ravenscroft composed eleven. He also composed ten anthems and a motet and in 1621 he published a metrical psalter, The Whole Booke of Psalmes.![]() 4

4

![]() 5 In this form the tenderness of the Ravenscroft version has given way to irony and the two crows, who replace the three ravens, are overheard to comment cynically:

5 In this form the tenderness of the Ravenscroft version has given way to irony and the two crows, who replace the three ravens, are overheard to comment cynically:

![]() 13 He writes that:

13 He writes that:

![]() 18

18

![]() 19 It is reasonable to assume that since the air was collected it must have been in circulation long enough for it to become established in the tradition. However, we do not know if it was collected as a tune or a song. Nonetheless, Child clearly deemed it to be worthy of mention. In the section 'Additions and Corrections' of volume 5 of the The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Child prints a version of The Three Ravens collected in Lincolnshire in 1793. It was collected from a farm labourer who; '... had 'learnt it 'from his fore-elders'.' In this version the 'fallow doe' is replaced by 'a lady full of woe, as big with bairn as she can go.'

19 It is reasonable to assume that since the air was collected it must have been in circulation long enough for it to become established in the tradition. However, we do not know if it was collected as a tune or a song. Nonetheless, Child clearly deemed it to be worthy of mention. In the section 'Additions and Corrections' of volume 5 of the The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Child prints a version of The Three Ravens collected in Lincolnshire in 1793. It was collected from a farm labourer who; '... had 'learnt it 'from his fore-elders'.' In this version the 'fallow doe' is replaced by 'a lady full of woe, as big with bairn as she can go.'![]() 20 Frank Kidson collected a traditional fragment of the ballad from; '... Mr John Holmes, of Roundhay, [WestYorkshire], who first heard it about 1825 from his mother's singing. This was in a remote village among the Derbyshire hills, most aptly named Stoney Middleton.'

20 Frank Kidson collected a traditional fragment of the ballad from; '... Mr John Holmes, of Roundhay, [WestYorkshire], who first heard it about 1825 from his mother's singing. This was in a remote village among the Derbyshire hills, most aptly named Stoney Middleton.'![]() 1

1![]() 21 Here too the 'fallow doe' is replaced by; '... his lady full of woe, ...'.

21 Here too the 'fallow doe' is replaced by; '... his lady full of woe, ...'.

![]() 26

26

![]() 30 Furthermore, the Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA) has found no reference in its collections of the ballad The Three Ravens being traditionally sung in Ireland.

30 Furthermore, the Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA) has found no reference in its collections of the ballad The Three Ravens being traditionally sung in Ireland.![]() 31

31