Article MT068

Michael Turner

A 19th Century Sussex Fiddler

[This is another article in which I am testing a new way of displaying footnotes - though the footnotes are still fopund at the bottom of the article text. First, you will need to set your browser to 'always expand ALT text for images' - do this via start/settings/control panel/internet options/advanced. Having done that, placing your cursor on the red asterisk  next to the footnote number will 'pop up' a box containing the footnote text. It will remain on-screen for about 5 seconds, but you can do it again if you've not finished reading. Photo captions work the same way - Ed.]

next to the footnote number will 'pop up' a box containing the footnote text. It will remain on-screen for about 5 seconds, but you can do it again if you've not finished reading. Photo captions work the same way - Ed.]

The activities of this magazine in recording the memories and experiences of traditional musicians are nothing if not praiseworthy. Nevertheless by their very nature these activities suffer from an obvious limitation: it is only possible to converse with and record living musicians, whose memories at best go back only to the early part of this century. Such efforts, entirely valid as they are, do not give us information on the activities of earlier generations of musicians, or the social context in which they played. Yet if we are to understand how the tradition operated and flourished in its heyday such information is necessary. The past may not be such an impenetrable abyss as some might think, as I hope the material presented here on the Warnham fiddler, Michael Turner indicates. 1

1

Obviously, as with all historical work, one is limited by the sources available. Traditional music leaves very little in the way of written records, and any research project will leave tantalising gaps in the information which cannot be filled. Nevertheless, if the effort provides any insights at all it is surely worth it.

I

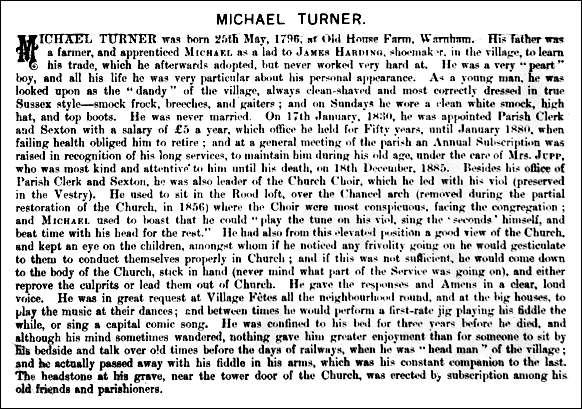

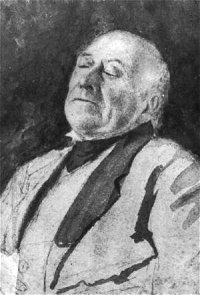

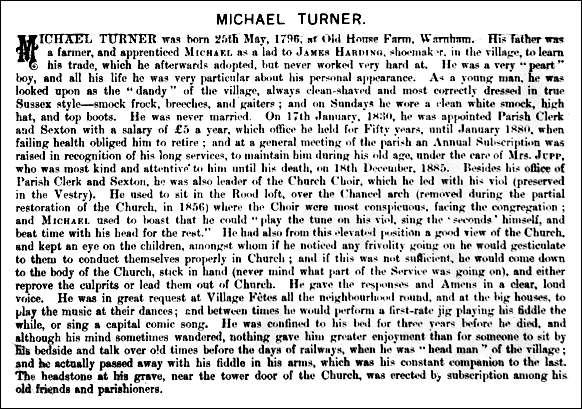

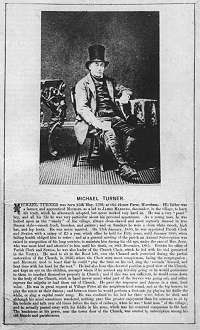

The fullest account of Michael Turner's life which we have is that reproduced here. It consists of a printed card together with photograph of Turner in his Sunday-best; along with most of the other material on him, the original will be found among the Warnham parish records deposited at the West Sussex Record Office, Chichester. 2

2  I can only add some minor details and corrections to this account: the location of Turner's birthplace old House Farm, until recently something of a mystery, has now been identified - the house, which is basically 16th century with major late Victorian additions, is now called Ends Place and lies just outside Warnham village; his pay seems to have been £10 a year and not £5, a fact recorded in the churchwardens' accounts. He also got extra fees for such activities as special bell-ringing, as in 1852 when he was paid 6d for having 'Told the Bell for Duke of Wellington'. No doubt he also got funeral fees for gravedigging, but these would not go through the wardens' accounts. Such pay as Turner received from the church would not have been sufficient to maintain him, and I therefore think that he combined his church activities with shoemaking until fairly late in life; two extant complete listings of the inhabitants of the parish list him as a shoemaker in 1841 (eleven years after he took up the job of parish clerk), and as Parish Clerk in 1871.

I can only add some minor details and corrections to this account: the location of Turner's birthplace old House Farm, until recently something of a mystery, has now been identified - the house, which is basically 16th century with major late Victorian additions, is now called Ends Place and lies just outside Warnham village; his pay seems to have been £10 a year and not £5, a fact recorded in the churchwardens' accounts. He also got extra fees for such activities as special bell-ringing, as in 1852 when he was paid 6d for having 'Told the Bell for Duke of Wellington'. No doubt he also got funeral fees for gravedigging, but these would not go through the wardens' accounts. Such pay as Turner received from the church would not have been sufficient to maintain him, and I therefore think that he combined his church activities with shoemaking until fairly late in life; two extant complete listings of the inhabitants of the parish list him as a shoemaker in 1841 (eleven years after he took up the job of parish clerk), and as Parish Clerk in 1871. 3

3

A second and briefer account of Turner is contained in a letter from C J Lucas, a member of the local gentry and churchwarden of St Margaret's, Warnham, to the redoubtable Canon K H MacDermott, in 1917.

MacDermott reprints most of this in his Sussex Church Music in the Past, page 79. This account gives the date of the removal of the rood loft as 1847, not 1856, and describes Turner as 'Master man and leader of the choirband'. It indicates (as is also clear from the churchwardens' accounts) that the church band consisted of a fiddle (usually referred to as a 'viol') a clarinet ('clarionet') and a 'cello ('bass viol').

Michael Turner spent his last five years of life in poverty and was dependent on charity (one is reminded of the reason behind Henry Burstow's book). 4 The vestry minutes illuminate this point:

4 The vestry minutes illuminate this point:

'It was then proposed and recommended that a vote of thanks be conveyed to Michael Turner for the Satisfactory and business like manner he has carried on the duties of Parish Clerk for the last 50 years. Carried unanimously.

The vestry also raised a Voluntary subscription for the maintenance of the Old and respected Clerk to be taken to his Friends and Parishioners...' 5

5

I have not been able to trace an obituary of Turner and there is no mention of him in the issue of the parish magazine appearing immediately after his death. Perhaps this is just chance, but the sources do seem to imply that he was not much thought of after his retirement, at least until some time after his death. The cost of his gravestone, £4 18s 11d was paid by the parishioners, but it was not erected till 1887. Ironically it was delivered by The London Brighton and South Coast Railway, the agency Turner thought responsible for the break up of the old village ways. 6

6

One point which the two accounts do not give us information on is the fact that Turner was a good bell-ringer. Henry Burstow gives some information on this,  noting that on Christmas eve 1846 he was standing with a friend at the bottom of the Bishopric in Horsham:

noting that on Christmas eve 1846 he was standing with a friend at the bottom of the Bishopric in Horsham:

'. .'twas a clear, frosty evening, with the wind in the north, and as we stood we heard the six Warnham bells ringing beautifully. I proposed going over there and we started at once.'

Upon arrival at Warnham among the ringers Burstow found Turner ringing number three. They must have become good friends for Turner provided Burstow with information on Sussex bells, was the source of some of Burstow's 420 songs, and rang the treble at Burstow's wedding in 1855. 7

7

II

Turner left behind two manuscript books of dance music. 8 The first book is dated 1845 and 46 - 47 - 48 - 49' (for facsimiles of the index pages and pp. 40-41 see centre pages). It contains 28 titles as follows:

8 The first book is dated 1845 and 46 - 47 - 48 - 49' (for facsimiles of the index pages and pp. 40-41 see centre pages). It contains 28 titles as follows:

- The Royal Irish Quadrilles (Jullien)

- Die Elfen Waltz

- Polish Polka

- The Opera Polka

- Galop

- Les Rats Quadrilles

- Gallopade

- Auriora Waltz

- Jullien's Celebrated Waltz

- The Original Scottische Polka

- The Bridal Polka

- The Original Scottische Polka (Jullien)

- Redowa Polka

- The Drum Polka (Jullien)

|

- La Rosa Waltz (Incomplete and Inverted)

- Waltz-My Skiff is on de Shore (Inverted)

- La Rosa Waltz

- The Planet Waltz

- The Planet Quadrilles

- The Queen Celerious Waltz

- Peshat Waltz

- Country Dance - Jubal, Cain

- Post Horn Gallop Continental

- The Bohemian Polka

- Jenny Lind's Polka

- La Regalia D'Angleterre (Camille Schubert)

- The English Quadrille

|

The second book, dated 1852, contains 16 titles as well as 42 psalms and hymn tunes at the other end of the book (for facsimiles of sample pages see centre pages and opposite, p. 18). The dance pieces are:

- B Quadrilles

- Jeannett & Jeannott

- The Dark Set of Quadrilles

- Russells Qua(drille)

- The Edinburgh Quadrille

- There(s) no Luck (Part 3 of the above)

- The Celebrated Opera Polka

|

- First Set Heidelberg

- The Bridal Waltz Waltz

- The Edinburgh Musical Fund Waltz Country Dance

- Welch air Sweet Richard

- Pop Goes the Weasel (With dance instructions)

- La Tempete The Military Sco(ttische)

|

The quadrilles are in five parts, different rhythms equating to the five sections of the dance.

From these lists there can be little doubt that Turner was very much a 'pop' musician of his day. The waltz and the polka were both new idioms in the 19th century, and when Turner compiled his books the polka was particularly new. But this is not the whole story for on the fourth page of the earlier book Turner gives a list under the heading 'Country Dances', which only in the case of two tunes ties up with either manuscript:

- King of the Canible Islands

- In the Merry M of May

- Dance Boatman Dance, or Josea

- There's nae Luck

- Rory O'more

- Lucy Neale

- Off She Goes

- May Moon

- The Ivy Green

- The Ile France

- Collage Hornpipe

- Nancy Dawson

|

- le Seear

- Captn. Whyke

- Quadrille Love

- La Poule

- The White Cockade

- Jubal Cain

- Richmond Hill

- Haste to the Wedding

- Henlock

- Waterlow Dance

- The Flowers of Edinburgh

|

Here we are on much more familiar ground. There are some mysteries, but a good proportion of the tunes listed are still current or have been recently collected from traditional musicians, e.g. Off She Goes and Haste to the Wedding. Others are ubiquitous like College Hornpipe, The White Cockade and The Flowers of Edinburgh. Henry Burstow tells us that Rory O'More was in the somewhat limited repertoire of the Horsham Town Band in the 1830s. 9 Did Turner know these from memory or was there a third manuscript book that has failed to survive? Were they simply tunes suitable for dancing or did Turner know actual dances to each specific tune as he did with Pop goes the Weasel?

9 Did Turner know these from memory or was there a third manuscript book that has failed to survive? Were they simply tunes suitable for dancing or did Turner know actual dances to each specific tune as he did with Pop goes the Weasel?

The only items in the manuscripts which have been 'recovered' from traditional sources are as far as I know Jenny Lind's Polka, Pop goes the Weasel and La Tempete. Jenny Lind's is interesting in being a much more elaborate version than the traditional renditions I have heard, and possessing a third 'trio' section. This seems to have obviously been copied from print as do most of the tunes in the manuscript.

The list of country dances remains a bit of a mystery. In his 1917 letter C J Lucas writes of 'the description of the rules for the various dances' (my italics) which he finds 'very amusing'. The use of the plural here implies more dance descriptions than just Pop goes the Weasel, and unless they turn up at some time we must suppose them lost. Unless, that is, Lucas referred to the printed collections which Turner possessed.

Turner's printed books seem very unlikely for a 19th century fiddler to have, for among other, things he had a copy of John Playford's 1665 edition of the Dancing Master, Playford's Introduction to Music and Introduction to the Playing on the Viol and on the treble violin and Thomas Campion's Art of Descant, all of 1664. 10 If, as I suspect, Turner's musical literacy was largely self-taught, we have the extremely interesting phenomenon of a 19th century village musician learning from 17th century self-tutors. We do not know what, if anything, Turner made of Playford's dance instructions or the more courtly sounding tunes in the collection. Here we quickly enter the realms of speculation.

10 If, as I suspect, Turner's musical literacy was largely self-taught, we have the extremely interesting phenomenon of a 19th century village musician learning from 17th century self-tutors. We do not know what, if anything, Turner made of Playford's dance instructions or the more courtly sounding tunes in the collection. Here we quickly enter the realms of speculation.

III

The Turner collection and the information uncovered about his life probably raise more questions than they answer. I do not think it is possible to draw out any hard and fast conclusions about the things discussed below, but I do feel that the material supports certain provisional conclusions and hypotheses which may suggest lines of future enquiry and are therefore worth setting out.

The Turner collection and the information uncovered about his life probably raise more questions than they answer. I do not think it is possible to draw out any hard and fast conclusions about the things discussed below, but I do feel that the material supports certain provisional conclusions and hypotheses which may suggest lines of future enquiry and are therefore worth setting out.

In the first place the Turner material and other evidence I have come across suggest a strong link between the church bands and traditional dance music. Everybody must be familiar with Thomas Hardy's accounts of the church band in Under the Greenwood Tree and Absent-mindedness in the Village Choir. The evidence suggests that the sort of relationship Hardy put into his fiction did in fact exist. [Hardy was in a good position to write accurately about village music in the 19th century as he himself played the fiddle with his father for dancing and in church. Photocopies of the family tune-books, which resemble those described here in appearance and content, are available for study in the Library at Cecil Sharp House - Ed] Owing to the activities of MacDermott a fair amount of information is available on the Sussex church bands, and incidentally MacDermott gathered examples of secular tune books whilst engaged in researching religious music. In particular the collection of dance music that belonged to the Welch family of Bosham is a very rich source, and much more 'traditional' in content than the Turner manuscripts.

On the simple level of instrument purchase and maintenance costs the church bands probably played a very important role. Here is an extract from the Warnham churchwardens' accounts just after Turner took over as Parish Clerk:

| 1832 | | £ - s - d

|

| Nov | 23 | A bass Viol String and 2 Violin Strings | 2 6

|

| | 27 | Paid for repairing bass at Coleman's Ockley | 5 0

|

| Dec | 22 | Bass string and violin string | 2 0

|

| | 28 | 2 bass and Violin Strings | 1 4

|

| 1833

|

| Feby | 11 | Stuff for bass viol bagg | 2 7

|

| | Making | 1 3

|

| | A bagg for the Clarionet | 1 6

|

| April | 28 | A Violin string | 6

|

| July | | A First and 2 Violin String | 1 4

|

| 1834

|

| March | 16 | Paid Henry Charman for One set of Bass Viol Strings | 4 0

|

| | One flask of oil for the clock | 1 6

|

| May | 7 | Settled Mich. Turner  11 11 | £1 6 11

|

Bear in mind this was a period of great distress among the lower classes of rural society. In 1830 the skyline of Sussex had been set aglow with the rickburning activities of 'Captain Swing', and the social fabric had been torn apart along with the threshing machines.  Wage rates were relatively high in Sussex an able-bodied farm worker could get 2s 6d in summer and 2s 3d in winter - but the threat of unemployment was constant.

Wage rates were relatively high in Sussex an able-bodied farm worker could get 2s 6d in summer and 2s 3d in winter - but the threat of unemployment was constant. 12 Henry Burstow estimated that he earned an average of 15s per week for most of his life.

12 Henry Burstow estimated that he earned an average of 15s per week for most of his life. 13 Bearing such amounts in mind it can be easily seen that little would be left for such luxuries as musical instruments; hence the significance of the church's support for musicians. It also accounts for the number of home- or village-made instruments that crop up in various places; Bosham church once had a 'cello made of thin copper.

13 Bearing such amounts in mind it can be easily seen that little would be left for such luxuries as musical instruments; hence the significance of the church's support for musicians. It also accounts for the number of home- or village-made instruments that crop up in various places; Bosham church once had a 'cello made of thin copper. 14

14

Another important influence of the church bands was in the spreading of musical literacy. Well over 100 bands are recorded as having existed in Sussex  15 and whilst it would be foolish to assume that every member of every band could read music I think it would be equally mistaken to assume that few did. Musical literacy and the ability to perform in a traditional style are by no means incompatible; there is even evidence that Sussex congregations performed their metrical psalms in a style closer to American southern Baptists than modern Anglicans.

15 and whilst it would be foolish to assume that every member of every band could read music I think it would be equally mistaken to assume that few did. Musical literacy and the ability to perform in a traditional style are by no means incompatible; there is even evidence that Sussex congregations performed their metrical psalms in a style closer to American southern Baptists than modern Anglicans. 16

16

A musician such as Turner might well have been important in the process of tune dissemination. There are a number of ways a new tune might get into circulation among rural communities, but one that seems quite likely would be where a musician like Turner copied a tune from print and then played it in his community where natural musicians would pick it up. Turner also seems to have taken the trouble to copy pieces he heard and liked. It is notable that four of the pieces in the manuscripts are attributed to Jullien. Henry Burstow informs us that 'Jullien's celebrated Orchestra, from London' provided the music at two fancy-dress balls in the Horsham area held in honour of a young gentleman who had recently come of age, in January 1844. 17 Perhaps Jullien sold copies of his music to the local gentry who attended the ball and one was lent to Turner for copying. The dates certainly tie up.

17 Perhaps Jullien sold copies of his music to the local gentry who attended the ball and one was lent to Turner for copying. The dates certainly tie up.

The mention of Jullien's compositions in Turner's repertoire brings us to the vexed question of whether Turner can be classed as a traditional musician at all. Of course it depends entirely on how you define your terms. There is no agreed definition of the term traditional. Is traditional the form or the function? 18 Older generations of collectors and observers have paid attention to the formal aspects and ignored the functional; Lucy Broadwood did this when she chose only to take down certain of Henry Burstow's songs, those which conformed to her notion of what a folksong ought to be.

18 Older generations of collectors and observers have paid attention to the formal aspects and ignored the functional; Lucy Broadwood did this when she chose only to take down certain of Henry Burstow's songs, those which conformed to her notion of what a folksong ought to be. 19 Here is not the space to expand my own views on the subject but briefly I believe that tradition is a social process connected with autonomous functioning of activities within known forms; the content of tradition, its formal aspect, is secondary to the role that tradition plays within a community, its functional aspect. This is not to say that the formal aspect is without interest, but merely that the functional aspect is of prime importance.

19 Here is not the space to expand my own views on the subject but briefly I believe that tradition is a social process connected with autonomous functioning of activities within known forms; the content of tradition, its formal aspect, is secondary to the role that tradition plays within a community, its functional aspect. This is not to say that the formal aspect is without interest, but merely that the functional aspect is of prime importance.  Michael Turner was a musician who spent his whole life within a small rural community, he led the church band, he played the music for the dances at fetes standing on a tub, and at big houses around the area, when called upon he would sing a song, and a great singer like Burstow was prepared to learn from him. This man in social function was a traditional musician regardless of the exact mixture of 'traditional' or composed pieces he performed.

Michael Turner was a musician who spent his whole life within a small rural community, he led the church band, he played the music for the dances at fetes standing on a tub, and at big houses around the area, when called upon he would sing a song, and a great singer like Burstow was prepared to learn from him. This man in social function was a traditional musician regardless of the exact mixture of 'traditional' or composed pieces he performed.

Finally, a study of Michael Turner directs our attention to sociological and institutional aspects of traditional music. I have already mentioned the supportive role of the church to musicians. Both Turner and Burstow were shoemakers; is this coincidence or is it significant? Both were great characters and in their ways individualists. In both cases bell-ringing formed an important social basis for the performance of their songs and music. There are many sweeping and vague generalisations about the decline of traditional music in the 19th and 20th centuries; perhaps we should look much more closely at the changes within institutions that were supportive to traditional music and ceased to be: the church that bought Turner's fiddle strings in the 1830s ripped out the rood-loft and installed its first organ around the middle of the century. This was just one change among many in a rapidly changing society, but it may have vital significance. Turner fiddled out his 89 years, but I have found no information concerning a successor to his role as village fiddler. Turner's fiddle rests in a glass case in Warnham Church and Turner rests a few yards away in the churchyard; the village is losing its half-hearted fight against the invasion of modernity and mediocrity. What was once a thriving social centre is now a quiet backwater, an abode of the better-off type of commuter and the retired rich.

Vic Gammon - 1.8.00

This article first appeared in Traditional Music no.4, mid 1976, and is reproduced here with the collaboration of its author. The original publication appeared illustrated by pages from Michael Turner's manuscript books, which have not been retained here. The screen display of such items is notoriously poor, even when very clear originals are available to scan - not the case here, I'm afraid. They may be reinstated if I get access to better examples in the future - Ed.

Notes:

- Thanks are due to Ashley Hutchings who first put me on to Turner, I think by reading a reference in K H MacDermott's Sussex Church Music in the Past; all the subsequent research is by me. Thanks are also due to the Revd B R Spence, Vicar of Warnham, who went through material in the church looking for information on Turner for me. He was also kind enough to allow the illustrations in this article to be reproduced.

- West Sussex Record Office (WSRO) 203/7/12

- WSRO 203/9/1 wages; 203/7/6 population survey

- Henry Burstow, Reminiscences of Horsham, Chichester, 1911

- WSRO 203/12/1

- WSRO 203/ 4/ 7

- Burstow pp. 98, 87, 102, and 108

- WSRO 203/7/50 and 51

- Burstow p. 50

- WSRO 203/7/39 and 40

- WSR0 203/9/1

- E J Hobsbawm and G Rude, Captain Swing, passim and pp. 163-4 wage rates

- Burstow p. 23

- MacDermott p. 44

- MacDermott pp. 91-2

- MacDermott p. 26

- Burstow p. 45

- Traditional Music No.2 p. 27

- Burstow p. 110

Article MT068

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 1.8.00

I can only add some minor details and corrections to this account: the location of Turner's birthplace old House Farm, until recently something of a mystery, has now been identified - the house, which is basically 16th century with major late Victorian additions, is now called Ends Place and lies just outside Warnham village; his pay seems to have been £10 a year and not £5, a fact recorded in the churchwardens' accounts. He also got extra fees for such activities as special bell-ringing, as in 1852 when he was paid 6d for having 'Told the Bell for Duke of Wellington'. No doubt he also got funeral fees for gravedigging, but these would not go through the wardens' accounts. Such pay as Turner received from the church would not have been sufficient to maintain him, and I therefore think that he combined his church activities with shoemaking until fairly late in life; two extant complete listings of the inhabitants of the parish list him as a shoemaker in 1841 (eleven years after he took up the job of parish clerk), and as Parish Clerk in 1871.

I can only add some minor details and corrections to this account: the location of Turner's birthplace old House Farm, until recently something of a mystery, has now been identified - the house, which is basically 16th century with major late Victorian additions, is now called Ends Place and lies just outside Warnham village; his pay seems to have been £10 a year and not £5, a fact recorded in the churchwardens' accounts. He also got extra fees for such activities as special bell-ringing, as in 1852 when he was paid 6d for having 'Told the Bell for Duke of Wellington'. No doubt he also got funeral fees for gravedigging, but these would not go through the wardens' accounts. Such pay as Turner received from the church would not have been sufficient to maintain him, and I therefore think that he combined his church activities with shoemaking until fairly late in life; two extant complete listings of the inhabitants of the parish list him as a shoemaker in 1841 (eleven years after he took up the job of parish clerk), and as Parish Clerk in 1871.

noting that on Christmas eve 1846 he was standing with a friend at the bottom of the Bishopric in Horsham:

noting that on Christmas eve 1846 he was standing with a friend at the bottom of the Bishopric in Horsham:

The Turner collection and the information uncovered about his life probably raise more questions than they answer. I do not think it is possible to draw out any hard and fast conclusions about the things discussed below, but I do feel that the material supports certain provisional conclusions and hypotheses which may suggest lines of future enquiry and are therefore worth setting out.

The Turner collection and the information uncovered about his life probably raise more questions than they answer. I do not think it is possible to draw out any hard and fast conclusions about the things discussed below, but I do feel that the material supports certain provisional conclusions and hypotheses which may suggest lines of future enquiry and are therefore worth setting out.

Wage rates were relatively high in Sussex an able-bodied farm worker could get 2s 6d in summer and 2s 3d in winter - but the threat of unemployment was constant.

Wage rates were relatively high in Sussex an able-bodied farm worker could get 2s 6d in summer and 2s 3d in winter - but the threat of unemployment was constant. Michael Turner was a musician who spent his whole life within a small rural community, he led the church band, he played the music for the dances at fetes standing on a tub, and at big houses around the area, when called upon he would sing a song, and a great singer like Burstow was prepared to learn from him. This man in social function was a traditional musician regardless of the exact mixture of 'traditional' or composed pieces he performed.

Michael Turner was a musician who spent his whole life within a small rural community, he led the church band, he played the music for the dances at fetes standing on a tub, and at big houses around the area, when called upon he would sing a song, and a great singer like Burstow was prepared to learn from him. This man in social function was a traditional musician regardless of the exact mixture of 'traditional' or composed pieces he performed.