Between the two World Wars, Britain was a major centre for the recording and manufacture of gramophone records. In addition to activities in the United Kingdom, this involved location recordings, setting up manufacturing plants abroad, and making records in Britain for foreign importers. Records made by associated companies in the United States were also disseminated throughout the world.

Recordings by Africans and West Indians (including Cubans) demonstrate and illuminate two small aspects of this process. They also identify the role of migrant musicians in the evolution of the recording business in the United Kingdom.

From the outset, when companies were set up to make both gramophones and gramophone records in the 1890s, the scope of the enterprise was perceived as international. This is best explained by the actions of the two associated companies founded to exploit the invention of Emile Berliner: the Victor Talking Machine Company in the United States, and the Gramophone Company in Britain. Under commercial agreement, both companies assiduously pursued a policy of selling gramophones and making records in the territories in which they operated - Victor in the Americas (North and South) and the Far East; the Gramophone Company in the rest of the world (using the British Empire as the fulcrum for its operations).

Others joined in this bonanza, for example, Odeon (based in Germany) and Pathé (based in France). The Columbia Phonograph Corporation (Victor's principal rivals in the United States), also began to spread its net world wide.

Many of these enterprises changed hands several times. This and other factors (including the destruction of archive material) means that the history of their operations - in particular, those outside Europe or the United States - is little documented in general histories of the gramophone and gramophone records published in English. That such operations were of some significance in the rising fortunes of European and US companies will be shown by using evidence from an intact archive, that of the Gramophone Company (later EMI), one of the most important organisations active during this period.

In 1903, Zonophone (a troublesome rival), was purchased by the Gramophone Company and Victor (both of whom held the 'dog and trumpet' trademark), and thereafter was used by the European organisation as a marque for low-priced records, or export. In general, after 1910, Gramophone's principal lines were sold under the label of 'His Master's Voice' the 'dog and trumpet' or HMV marque). ![]() 1

1

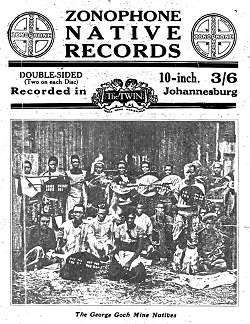

Two Zonophone export lines that concern this discussion were launched in May 1912: the general overseas 3000 series, and a 4000 series for the South African market. The latter is of immediate interest in that it reissued 'Gramophone' recordings made by a group of Swazi chiefs on a visit to London (c. late 1907-early 1908). In March- April 1912, Zonophone had also sent a recording engineer (G. W. Dillnutt) on a field expedition to South Africa. He obtained recordings in Afrikaans and in a variety of African styles. On release, the African performances were advertised as 'Zonophone Native Records'. They had been recorded in Johannesburg and included folk tales in 'M'xosa' by anonymous performers, items by the Abonwabisi Party (Don't Worry Entertainers), hymns by the Salvation Army Johannesburg 'Impi to Sindiso', and humorous and other material from the St Cyprian's Choir, H Selby-Mismang, and J B Masole. The George Goch Mine Natives sang in' Shangaan' and 'M'chopi'. In 'M'chopi' they were accompanied by 'native piano' (or mbira). Other languages represented in these recordings were 'Sechoana', 'Sesotho', 'Swazi' and 'Zulu'. ![]() 2

2

This move to expand into major and minor markets overseas was paralleled on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. For example, the Victor Company made a trip to Trinidad in 1914 to record the local repertoire of black music including 'calypsos' and 'kalendas'. Such activities were interrupted by the advent of the First World War. ![]() 3

3

During the War, one instrumental group that included English-speaking West Indians was recorded by Columbia in Britain. This was Ciro's Club Coon Orchestra. Their records (made in 1916 and 1917) reflected popular tunes of the period. After the War (in 1918 and 1919), Dan Kildare - a pianist with this group, who came from Jamaica - made records for the same company with Harvey White, as Dan and Harvey's Jazz Band.  The rhythm designations for these records indicate that they comprised Fox Trots and a Waltz. Despite the apparent urban origins of the musicians, however, their performances reflect black North American string band music.

The rhythm designations for these records indicate that they comprised Fox Trots and a Waltz. Despite the apparent urban origins of the musicians, however, their performances reflect black North American string band music. ![]() 4

4

Trade in new gramophone records for the English-speaking West Indies did not commence again until 1921, when the pianist Walter Merrick made records for Victor in New York with the Trinidad vaudevillian Johnny Walker. In Britain, it was not until the following year that Zonophone revived their interest in black music for the African market. In their 3000 series they reissued recordings in Yoruba, made for HMV in 1911, by Shoto Adeyemi (secular songs) or as C W A Pratt (religious songs). In London, they also made a great number of new religious recordings (22 couplings) by the Reverend J J Ransome-Kuti (grandfather of the late Nigerian 'superstar' Fela Fela). Ransome-Kuti (of Abeokuta, Nigeria) travelled to Britain specially 'so that Sacred Songs of his own composition and other records of interest [might] be available to all Yoruba speaking people'. As with 'C W A Pratt', the Reverend Ransome-Kuti's religious message was Christian rather than Yoruba in origin. Selection of the 3000 series by Zonophone indicates that their releases in this sequence were popular in West Africa (in this respect Nigeria), the region in which Yoruba is spoken. ![]() 5

5

New recordings for the West African market in 1922 were followed by a London session in October 1923 for Zonophone's 4000 South African series. The singer was Sol Plaatje, the black South African nationalist, who was on a visit to Britain. With piano accompaniment by Sylvia Colenza on some of the titles, he recorded six sides. Two were in 'Sechuana' and three in 'Si-Xosa' (or 'Xosa' ). There were two songs on one side of Zonophone 4168: Pesheya Ko Tukela (in 'Sechuana') and Nkosi Sikeleli Afrika (in 'Sutu' and 'Zulu'). The latter song was adopted by the African National Congress as their official anthem in 1919 and, possibly for political reasons, was omitted from at least one flyer published by the Zonophone Company advertising these gramophone records. ![]() 6

6

The general pattern for overseas African records manufactured in Britain throughout the 1920s was for performers to be recorded in the metropolis of London. Likewise, on the other side of the Atlantic, a few performers from the English-speaking West Indies (almost always Trinidad), travelled to New York City in the USA to make records for their local market. Lionel Belasco, a famous Trinidad bandleader and pianist (recorded by Victor in the island on their 1914 field trip), had moved there in about 1918. He made records for the English-speaking West Indies throughout the 1920s. Another Trinidad performer, the vaudeville singer, actor and journalist Sam Manning, moved to New York in 1924. In August he made his first records of Trinidad music.  These were issued in a West Indian series launched by the General Phonograph Corporation under their OKeh marque. In other instances companies travelled to the music makers to obtain their recordings. In the same period, for example, the Victor Company was recording Cuban music in both Havana and Mexico City, as well as New York.

These were issued in a West Indian series launched by the General Phonograph Corporation under their OKeh marque. In other instances companies travelled to the music makers to obtain their recordings. In the same period, for example, the Victor Company was recording Cuban music in both Havana and Mexico City, as well as New York.

In 1925, the Zonophone Company in London renewed their interest in recordings for the West African market. They engaged several singers for their 3000 series. M. Cole provided two songs in Ibo, and E. O. Martins two in Fanti. Each performer sang in their respective choruses, together with 'D Justice' and 'T K Brown'. Ladipo Solanke, later to become the leading light in the West African Students Union in Britain, performed Yoruba songs, philosophy and proverbs, and Roland C Nathaniels recorded several sides in Ewe, a coupling in Ibo, and another in Latin! On the basis of this and subsequent evidence, all these performers appear to have been domiciled in the United Kingdom. Ibo, like Yoruba, is spoken in Nigeria. Fante and Ewe are languages from Ghana (then known as the Gold Coast). Nathaniels was originally from Keta, a seaport in this region.

Technical improvements in the reproduction of recorded sound (recording and playing back records using new electrical process), arid the advent of mass-produced radios, spurred changes in the world-wide record business in 1925. One result was that the highly successful Columbia Graphophone Company in Britain (sold by their US parent in 1922) acquired US Columbia, thereby securing rights to a reliable electrical system for recording. Victor followed suit and licensed the same system, which was also taken up by the Gramophone Company. Also in the United Kingdom, Columbia s successful rise was consolidated by the purchase of the German based world wide record business of the Carl Lindstrom Company (who held the Odeon and Parlophone marques).

By 1926, electrically recorded discs were on sale in both the USA and Britain. This technical advance may have been one catalyst for the US Brunswick Company to advertise in the local press for a South African agent. This was taken up by Mitchell Paul of Durban. He went into partnership with Eric Gallo of Johannesburg. In competition with factors representing British companies, such as Gramophone and Columbia, Paul and Gallo distributed and retailed Brunswick records via their company Brunswick Gramophone House. Gallo subsequently bought out Paul's interest. Also in 1926, Columbia acquired Lindstrom's US affiliate, the General Phonograph Corporation, whose lines included the OKeh series aimed at the English-speaking West Indies. Parlophone (in Britain) were to release the complete OKeh West Indian series (as it stood at that time) in the United Kingdom in 1927. ![]() 7

7

With the success of electrical recordings, in 1927 the Gramophone Company made a determined effort to expand the market for its West African records. First, using the new process, further recordings were made by Roland C Nathaniels singing in Ewe. Issued in June, these were the final releases in the Zonophone 3000 series. In October, probably as a result of the conclusion of the 3000 numerical sequence, and in reaction to commercial competition, Zonophone launched a new line aimed at West Africa. With the letter prefix EZ, 25 double-sided records were issued at this time. The first 16 were sung in Fanti by George Williams Aingo. EZ 17 and 18, by Harry Quashie, were in the same language and the remainder (also by Quashie) were in Twi.

This Ghanaian orientation was short lived. Zonophone made a conscious effort to provide recordings in different languages. For example, early in 1928 Aingo recorded in Hausa (spoken in northern Nigeria) and by the end of the same year the company had recordings available in a wide range of West African languages, covering the area from Senegal (in the north) to Nigeria (in the south).  There were also East African languages in the catalogue: recordings in Somali by Aboukir Awad and in Swahili by the ubiquitous R C Nathaniels.

There were also East African languages in the catalogue: recordings in Somali by Aboukir Awad and in Swahili by the ubiquitous R C Nathaniels.

Like Nathaniels, George Williams Aingo and Harry Eben Quashie appear to have been living in Britain at this time. This seems to have been the case also for Domingo Justus and T K Browne. Both made records in Yoruba in 1928 (they had sung in the chorus for M C Cole and E O Martins three years earlier). Other musicians, however, were sponsored by commercial organisations based in West Africa. This was the arrangement for the Kumasi Trio (from Ghana) whose trip to London and recordings in June 1928 were made on behalf of the Tarquah Trading Company. They were released by Zonophone in a special numerical sequence, beginning EZ 1001. The exact reason for this is not known, as recordings by the majority of performers were allocated to the original series. In January 1928, Moffat Skye, a black South African singer visiting London, recorded six sides for Zonophone in Sesotho. These were issued in the label's 4000 series alongside 'Eulogies' and versions of Aesop's Fables in Zulu, recorded in 1927 by James Stuart (a British- born language specialist). Stuart made similar recordings in 1928 and in the same year sides were also cut by 'Mac Jackson and the Cape Coloured Coons' singing in 'Kitchen Dutch'.

Two new performers singing in Zulu were added to Zonophone's 4000 series in 1929. Both Simon Sibiya and John Matthews Ngwane were recorded in London during the year. There was also a major innovation with the release of recordings drawn from Old Time Music catalogue of the Victor Company in the US. These included performances by the Carter Family and the Georgia Yellow Hammers.

String band music was featured similarly in the Zonophone EZ series, but this was African in origin. In September a recording session by the West African Instrumental Quintet took place in London. The Quintet comprised two guitars, a banjo-mandoline or cavequinho, tambourine and other percussion. Some of the melodies employed by these musicians are very reminiscent of black creole music from the English-speaking West Indies.

In 1930 Zonophone issued further releases in Zulu in the 4000 series. These were by J M Ngwane (recorded 1929) and James Stuart. There were also more selections from the Victor Old Time Music catalogue. Included was a coupling by the Virginia ballad singer Kelly Harrell and more items by the Carter Family. The most significant South African events in 1930, however, commenced with a visit to Cape Town and Johannesburg by a Columbia Records field recording unit. Arriving in the middle of the year, important sessions were cut by African musicians.

From his base in Johannesburg, Eric Gallo was alert to the potential sale of these recordings. His Singer Gramophone Company was set up to handle releases by local performers and he immediately made arrangements for African records to be made in London. In late July, Griffiths Motsieloa (a vaudeville singer, elocutionist and actor, who had appeared on the London stage) was sent to the United Kingdom for this purpose. He left in great haste, attempting to allow Singer to overtake the first Columbia releases, but forgot his sheet music, which had to be mailed from South Africa by his wife. In the interim, Caluza's Double Quartet arrived in London to make records for Zonophone. They had travelled from South Africa at the behest of Mackay Brothers (the local agent for the Gramophone Company).

Reuben Tholakele Caluza was a skilled composer of topical songs in Zulu. He taught at the Ohlange Institute near Durban. His Double Quartet comprised four women and four men, who were students or teachers from mission schools in or around that city. They were undoubtedly very popular, for Zonophone recorded 150 sides by these singers, all of which were issued. In addition to recording all together, the combination split to perform as a Female Quartet, a Male Quartet and a Mixed Quartet. There were also solo items from several members of the group. It is reported that the songs they recorded comprised 45 compositions by Caluza, 30 of his arrangements, and 75 traditional pieces. Most were sung in Zulu, but two were in 'Sesuto' and five in 'Xosa'. Some were performed a cappella, but in others Caluza provided piano accompaniment, or played the harmonium for Christian hymns. Alongside the folk songs there were vaudeville pieces and ukureka or 'ragtime songs'. The latter were influenced by syncopated music from the USA, but often through the mediation of 'composers' such as Stephen Foster. One of Caluza's most popular Zulu 'ragtime songs' was uBungca (Oxford Bags). A song of social commentary, this depicts the lifestyle of the black middle class in Durban during the 1920s and reflects on particular fashions for clothing, including 'Oxford Bags' from Britain:

| Nxa nivakashela eTheknwini, | When visiting Durban. |

| niyozibon' intomb' eziphambili, | you will see beautiful girls, |

| zingena ziphum' emawotela. | entering hotels. |

| Nezintomb' eziphambili. | Elegant ladies. |

| Niyobon' izinsizwn eziphambili. | You will also see elegant young men. |

| Zingen ewoteln lika T.D. | They enter T.D.'s hotel |

| zithi woza In wetha, kukhona kudla kuni? | and call the waiter, and ask him: "What kind of food do you have?" |

| Akubalek' uwetha ukudl' okukhona. | Or they ask the waiter to bring the menu. |

| Zithi leth' isitshulu leth' ilayisi. | Then they will say: "Bring stew and rice." |

| Letha noloz'bhifu nom' inyama yesiklabhu. | "Bring roast beef or mutton." |

| Zizangez' gubhu imsiko yase-Merika. | They are dressed in American style. |

| Abanye fak' isitali, behamba bebhungca | Some will come dressed in Italian style, with trousers, |

| znbeqhenya beti njengomkholwane, | the legs tied like a red-billed hornbill. |

| bhungca ngesitaliyana. | as in Italian trousers. |

| Manie beza ngamn Oxford bags. | Some come with their Oxford Bags |

| bafake kanye nama double breast coat. | and wear a double-breasted coat, |

| bafak' iziggok' zyizimhenge | big brimmed hats. |

| zamakawa z'vakina intombi, | There are also fashionable girls, |

| amasilik' avuzayo, nnmabhant.sh' akhindiwe. | short ladies dresses, |

| Kukhon' izintomb' eziphambili | expensive silks, short coats. |

| kukhon' ez' fana no dadenje. | and also ones just like you and me. |

| Nezinsizw' ezinasay' emakhaya. | And young men who go back no more to their homes. |

| Imihiuqa nemigovu. | Old crooks and hobos. |

| Zibanjiwe banjiw' eSamseni. | They are trapped in Samseni. |

| Iyabagwinya iMavville. | Mayville is the only place for them. |

| Bavakhala haynlamh' omam' ekhaya. | Their women at home are crying and suffering. |

| Yek' usizi olukululwe zinsizwa. | It is sad, gentlemen. |

| Kunjani na eGoli? | How is Johannesburg? |

| Zinjani na siqat' eGoli? | How is the liquor in Johannesburg? |

| Babanjelw' isiqata nesigomfana. | They are being arrested for concoctions brewed in their homes. |

| Yiwo lo umvozo wokubhunguka. | That is the price of forgetting one's relations. |

Recorded on 7 October 1930, uBungca was released later in the same month as one side of the first coupling by Caluza's Double Quartet (Zonophone 4276). ![]() 8

8

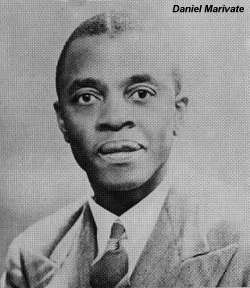

Eric Gallo had arranged with Metropole Industries Ltd to record and manufacture his Singer records for the South African market. On the arrival of Griffiths Motsieloa's music he, and three South African students resident in Britain, recorded over 40 sides at Metropole's studio in the Athenaeum, Hornsey. The students were Samuel Putsoane, Conference Setlogelo and Ignatius Monare and their releases were issued as 'Griffiths Motsieloa and Company' or other permutations in which individual performers were named. Their repertoire represented six languages: 'Sechuana', 'Sepedi', 'Serelong', 'Sesuto', 'Sixosa', and 'Zulu'. Singer followed this early in 1931 by sending another group to London under the leadership of Daniel Marivate and also recorded Miss Nomvula Mazihuko. This broadened the label's coverage of black southern African music, with performances sung in 'Chicaranaga', 'Sepedi', 'Sesuto', 'Shangaan', 'Sindebele', 'Tshvenda' and 'Zulu'. From 1933 or 1934 (after Metropole had withdrawn from the recording business), Decca manufactured records in Britain for Brunswick/Singer/Gallotone in South Africa. This lasted until 1949, when Gallotone set up its own facility. ![]() 9

9

The success of the recordings by Caluza's Double Quartet can be measured by the fact that between October 1930 and February 1932, two thirds of the titles they had recorded were released by Zonophone. In the same period, interspersed with the 52 Caluza releases, there were more selections from the Old Time Music catalogue of the Victor Company in the USA. The Carter Family continued to be featured, including Sara and Mabel Carter's performance of the black American ballad John Hardy (Laws I2). There was also an authentic cowboy song by Powder River Jack and Kitty Lee. In addition, Zonophone issued more string band music, by the Floyd County Ramblers (from Virginia) and the Taylor-Griggs Louisiana Melody Makers. The Woodie Brothers from North Carolina were allocated a coupling and there was a side by Grayson and Whitter (a popular duo from the Appalachian Mountains). ![]() 10 Another feature was Scandinavian items from respective Victor and HMV catalogues.

10 Another feature was Scandinavian items from respective Victor and HMV catalogues.

It appears that the Old Time Music recordings were sold to black as well as white purchasers. This is suggested by advertisements placed in the black press in 1930, that featured Zonophone's 'Zulu' recordings alongside releases by Jimmie Rodgers in the company's British 5000 series. Rodgers, the hugely popular 'singing brakeman' from Mississippi was renowned for his 'blue yodels'. He was one of Victor's most successful Old Time Music performers, and several of his recordings appeared in Zonophone's 4000 series in 1932. Releases of his records were also popular in other areas of Africa. ![]() 11

11

While in London in 1930-31, Reuben Caluza participated in the cultural life of the British capital. He spent time with Paul Robeson, the celebrated black American actor and singer, who was living in the city. He made broadcasts and was also introduced to the Master of the King's Music, Sir Walford Davis. In addition, Caluza was engaged by the School of Oriental and African Studies to help with the teaching of Zulu phonetics. After this he left for the United States, where he studied at the Hampton Institute and Columbia University. ![]() 12 Members of his group met with success on their return to South Africa. In particular Nimrod Makanya (tenor with the Double Quartet), who became the leader of the Bantu Glee Singers.

12 Members of his group met with success on their return to South Africa. In particular Nimrod Makanya (tenor with the Double Quartet), who became the leader of the Bantu Glee Singers. ![]() 13

13

Between 1929 and 1931 major changes took place in the ownership of the principal gramophone record companies in Britain and the United States. In 1929, the Radio Corporation of America took control of the Victor Talking Machine Company in the USA. Two years later, Columbia in Britain sold its controlling interest in the company's North American branch. This heralded the formation of Electrical and Musical Industries in Britain. The new organisation merged the world-wide activities of the Gramophone Company with the recording and other businesses controlled by Columbia in Britain and elsewhere.

At the same time, changes also took place in the recording of African music by these companies. There was a trend towards making recordings on location in Africa.  In this respect virtually the last releases in Zonophone's general West African series (EZ 570-572) were issued in June 1930. Featured were recordings made by George Wílliams Aingo in London as early as November 1928.

In this respect virtually the last releases in Zonophone's general West African series (EZ 570-572) were issued in June 1930. Featured were recordings made by George Wílliams Aingo in London as early as November 1928.

During 1930, or early in 1931, Odeon (the German marque controlled by Columbia in Britain) had sent a team to Nigeria. The recordings they obtained are recognised as the earliest examples of local music styles. It is possible that the same organisation began making records at other locations in West Africa at that time. ![]() 14

14

With the formation of EMI in April 1931, Gramophone and Columbia were no longer in direct competition. This may be another reason why Zonophone withdrew from the West African market. In South Africa, there was also a change in direction for Zonophone. In March 1932 HMV launched a new series aimed at black purchasers. The first 52 releases in this series (HMV GU 1 to GU 52) comprised all the Zonophone 4000 series couplings by Caluza and his Double Quartet. These were followed by 23 more Caluza records (ending GU 75). The next items in this series were from recordings made in Johannesburg in November 1932 by the Bantu Glee Singers (led by Nimrod Makanya). Singer began making location recordings in South Africa during the same period, although their first successful masters were not obtained until about 1934.

Zonophone continued to release material from Victor's Old Time Music catalogue until the 4000 series ended in 1934. This policy of distributing recordings made by a US affiliate to other parts of the world was continued by EMI. During the 1930s, these activities included another North American fashion, contemporary Cuban music.

The spectacular success of Cuban music world wide during the 1930s can be attributed to one musical composition. This is El Manisero (or The Peanut Vendor). Based on a street cry (or pregón) the song was written by the prolific Cuban composer Moïses Simóns. His piece was intended originally for the famous Cuban actress, singer and pianist, Rita Montaner. Nicknamed 'la unica' by her adoring audience in Havana, she made the first commercial recording of the song. It was cut by US Columbia during their field trip to the island, probably in November 1927 (Columbia 2965-X). ![]() 15

15

In Cuba during the 1920s,a particular form of African-American local music became popular. This was the son. The widespread island interest in this musical style was consolidated by regular recordings made by US gramophone companies in their drive to sell products in Latin America. By the end of the decade, the market for recordings of Cuban music had become a mainstay for the Spanish-American catalogues of Columbia, Victor and their rivals. The Victor Company, for example, recorded 'El Manisero 'Son Prégon', performed by Miguel de Grandy, in New York on 15 June 1928. This was issued in their general ethnic series (Victor 81412). Just over a year later (26 July 1929), the company recorded another version. Released in the 'Spanish' series, the performers were the Trio Matamoros (Victor 46401). ![]() 16

16

With their history of expanding markets for different kinds of music, it was natural for Victor to attempt to introduce the son to a wider audience. For this purpose they took the opportunity to record Don Azpiazu and his Havana Casino Orchestra. This band had arrived in New York from Cuba during the spring of 1930. They opened at the Palace Theatre on 26 April. The aggregation included a full Cuban rhythm section (with African-derived percussion instruments).  In addition, more conventional brass and string instruments were played in an unconventional manner. There was a complement of 'rumba' dancers. The band's repertoire comprised the new African-Cuban compositions of Simóns, Ernesto Lecuona and Elíseo Grenet (to name three prolific writers in this style). Azpiazu engaged Antonio Machín as his vocalist. Gifted with a fine tenor voice, Machín had gained a rapid reputation as a singer of sones. He had made his first recordings with a Sexteto under his leadership in Havana in September 1929.

In addition, more conventional brass and string instruments were played in an unconventional manner. There was a complement of 'rumba' dancers. The band's repertoire comprised the new African-Cuban compositions of Simóns, Ernesto Lecuona and Elíseo Grenet (to name three prolific writers in this style). Azpiazu engaged Antonio Machín as his vocalist. Gifted with a fine tenor voice, Machín had gained a rapid reputation as a singer of sones. He had made his first recordings with a Sexteto under his leadership in Havana in September 1929. ![]() 17

17

On 13 May 1930, Victor recorded Azpiazu's version of El manisero under its English title of The Peanut Vendor. Machín provided the vocal. The company was uncertain of the tune's acceptability for dancing and gave it the rhythm description 'Rumba Fox Trot'. Later in the month they recorded the band performing two conventional Fox Trots, and these comprise the first release under Azpiazu's name (Victor 22441). It was not until 2 July that they obtained a suitable coupling for The Peanut Vendor. This was Amor Sincero (or True Love), a son composed by Elíseo Grenet. The record was finally released in Victor's US domestic series in September 1930 (Victor 22483). Somewhat to the surprise of the company, it was a huge success and sparked a rage for 'rumba' records and films in the United States. ![]() 18

18

From early in the century, Europe and the United States sustained an interest in Spanish-American dances with the popularity of the tango. In this period, and until the late 1920s, it seems that Cuban musicians looked primarily to Spain for transatlantic recognition of their national songs and dances.  In Paris, however, a change in attitude towards music from the Caribbean was signalled by the end of the 1920s on the arrival of an exciting band of musicians from Martinique. Led by the prominent clarinettist Alexandre Stellio, their recordings for French Odeon, on 16 October 1929, register the beginning of the popularity of the biguine as a song and dance form in France. Stellio's band recorded five biguines and one mazouk (mazurka). Three months later (on 25 January 1930), a Cuban band led by Eduardo Castellalnos also recorded for the same company. They performed two danzonés and two sones. Cuban music, however, was not to capture the imagination in Paris for more than a year. In the interim, the Gramophone Company division of EMI played their part in disseminating Don Azpiazu's Peanut Vendor throughout Europe and the antipodes. Beginning in June 1931, HMV released this title in Australia, New Zealand and Holland (June); Spain, Denmark and France (July); Belgium (August); and Italy and Switzerland (September). In France the song was known as Le Marchand de Cachuétes (HMV K 6237) and its success may have encouraged its composer, Moïses Simóns to travel to Paris. Simóns, who was also a pianist, was certainly in Paris by September 1931. In that month he made two sides for HMV directing a band organised by the Cuban musician Filiberto Rico. The pieces were a rumba and a son and were both Simóns compositions (HMV K 6362). Rico's Creole Band was playing at 'La Coupole' in Montparnasse at that time and comprised musicians from both the French- and Spanish-speaking Caribbean. A multi-instrumentalist, Rico played flute, clarinet and saxophone with equal facility.

In Paris, however, a change in attitude towards music from the Caribbean was signalled by the end of the 1920s on the arrival of an exciting band of musicians from Martinique. Led by the prominent clarinettist Alexandre Stellio, their recordings for French Odeon, on 16 October 1929, register the beginning of the popularity of the biguine as a song and dance form in France. Stellio's band recorded five biguines and one mazouk (mazurka). Three months later (on 25 January 1930), a Cuban band led by Eduardo Castellalnos also recorded for the same company. They performed two danzonés and two sones. Cuban music, however, was not to capture the imagination in Paris for more than a year. In the interim, the Gramophone Company division of EMI played their part in disseminating Don Azpiazu's Peanut Vendor throughout Europe and the antipodes. Beginning in June 1931, HMV released this title in Australia, New Zealand and Holland (June); Spain, Denmark and France (July); Belgium (August); and Italy and Switzerland (September). In France the song was known as Le Marchand de Cachuétes (HMV K 6237) and its success may have encouraged its composer, Moïses Simóns to travel to Paris. Simóns, who was also a pianist, was certainly in Paris by September 1931. In that month he made two sides for HMV directing a band organised by the Cuban musician Filiberto Rico. The pieces were a rumba and a son and were both Simóns compositions (HMV K 6362). Rico's Creole Band was playing at 'La Coupole' in Montparnasse at that time and comprised musicians from both the French- and Spanish-speaking Caribbean. A multi-instrumentalist, Rico played flute, clarinet and saxophone with equal facility.

The major change in fortune for Cuban musicians in Paris took place in 1932. At the beginning of the year, a band led by Emilio 'Don' Barreto was employed by Melody's Bar (a night club in Montmartre). His brief was to play jazz and biguines. A Cuban-born banjo player who had changed to playing guitar, Barreto was struck by the success of black creole music from a sister island in the Caribbean. He determined, therefore, to introduce similar music from his own island into the band's nightly performances. Barreto's playing of danzonés and sones met with immediate success and, in the words of French researcher Alain Boulanger, 'Melody's became in a few days one of the most famous places in Paris'. Montmartre cabarets switched to playing Cuban music en masse. ![]() 20

20

On 3 May 1932, 'Don Barreto et son orchestre cubain du Melody's Bar' recorded their first session in Paris. This was organised by French Columbia. The music was a mixture of biguines and rumbas and was played by a band that included Filiberto Rico, on clarinet or flute, and Marino Barreto (the brother of Emilio Barreto) on piano. The popular French performer Jean Sablon sang Beguin–Biguine (Columbia DF 878). The success of Don Barreto and his records was noticed by Decca in Britain. Two months later, they flew the band from France for a session in London, which took place on l5 July.  Raymond Gottlieb, a Frenchman, replaced Marino Barreto on piano, but the band was otherwise the all-Cuban group that had recorded for Columbia.

Raymond Gottlieb, a Frenchman, replaced Marino Barreto on piano, but the band was otherwise the all-Cuban group that had recorded for Columbia. ![]() 21

21

Barreto recorded nine rumbas and four biguines at this session. Asi Pare, one of the biguines, had been recorded by Stellio for Odeon in 1930. Biguine d'Amor was written by Rico. It should be remembered that titles and rhythm descriptions for such pieces are not always finite. For example, Oh! Miss Liza (a biguine from Barreto's session for Columbia) is a version of a mento from Jamaica usually called Sweetie Charlie. Similarly, a rumba the band recorded for Decca - Lamento Esclavo, by Elíseo Grenet - is designated lucumí in another recording of the song. This was made by Rita Montaner for Columbia in New York in 1929. (Lucumí is an African-Cuban cult based on Yoruba religious principles). Juramento(s) another tune designated rumba by Decca, was described as a bolero when recorded by the trio led by its composer, Miguel Matamoros, in New York in 1928. ![]() 22

22

Don Barreto continued to make records for Decca for several years, but his subsequent recording sessions were held in Paris. Many of his sides for this company were released in Britain, including all but one of the items he cut in London in July 1932.

Evidence from recordings shows that there was an influx of Cuban musicians to Europe during 1932, and this is confirmed by contemporary recollection. In April, HMV in Spain recorded the 'Orquesta "Los Siboneyes"' under the direction of Ciro Deswal. Two months later they obtained performances from the 'Orquestra Elíseo Grenet' (16-17 June). France, however, was the focal point for 'Don Azpiazu et son Orchestre'. His band travelled from New York for engagements in various European locations (including London). They played major seasons in Monte Carlo and the French capital. Five days after recording a new session by Rico's Creole Band in Paris, HMV obtained six performances from Azpiazu's aggregation (10 October). On release, these were designated rumbas, using the contemporary catch-all description for Cuban music. While in France, Azpiazu also provided the music for a film made by the celebrated Argentine tango singer Carlos Gardel. ![]() 23 After another session for French HMV, on 25 January 1933, the band broke up and Azpiazu returned to New York.

23 After another session for French HMV, on 25 January 1933, the band broke up and Azpiazu returned to New York.

Another Cuban musician who returned home during this period was the composer and pianist Ernesto Lecuona. He was taken ill whilst touring in Spain. By this time, however, he had brought an 'Orquesta' from Cuba to join him in Europe. They made records for HMV in Madrid on 31 October and 1 November 1932. As with some members of Azpiazu's 'Orchestre', Lecuona's band remained in the continent following the departure of their leader. This added greatly to the pool of Cuban performers active in Europe.

In 1933, the influence of Cuban music in Britain was not particularly significant. EMI's Gramophone Company division, however, was alert as ever to contemporary trends. They were probably encouraged by the success of Don Azpiazu's recordings. In August, therefore, HMV inaugurated an export line featuring Latin American music. Aimed initially at India and West Africa, this was the HMV 'GV' series. Nine 78 rpm records were issued at this time. Seven were couplings from RCA Victor's 'general ethnic' or 'Spanish' (American) catalogues, recorded between 1927 and 1930. Six of these featured African-American music from Cuba, the other (GV6) was Puerto Rican. They had been recorded in the USA or Cuba. The initial release in the series (GV 1) was Azpiazu's The Peanut Vendor with its original coupling of True Love (from RCA Victor's US 'domestic' catalogue). In addition, one side of GV 3 was the 1929 version of E1 Manicero 'Pregon son' [sic] by the Trio Matamoros 'con dos guitarras'. GV 9 was drawn from the second of the two couplings by the 'Orquesta "Los Siboneyes"' that HMV had recorded in Spain. A mix of HMV and RCA Victor sources was maintained throughout the 'GV' series, which became very popular among black purchasers in West (and East) Africa. ![]() 24

24

Contrary to many reports, the band brought to Europe by Ernesto Lecuona in 1932 never toured the continent under his leadership. ![]() 25 With his permission, however, they took the name Lecuona Cuban Boys. Throughout 1933 and 1934, this group began to build a reputation as interpreters of Cuban music in various European locations. In the Autumn of 1934, the novelty of their performances had attracted film makers in Britain who engaged them 'to appear with Les Allen [a crooner] in the Gainsborough film The Code'. According to a report in the Melody Maker, 'Alex Kraut - the supreme novelty spotter of the recording business' became aware of the band's 'extraordinary cleverness'. He decided, therefore, 'to put them out on Regal-Zono[phone] introducing the new dance, the Conga'. (Regal-Zonophone was EMI's low-priced label, that had been launched after the Columbia-Gramophone merger).

25 With his permission, however, they took the name Lecuona Cuban Boys. Throughout 1933 and 1934, this group began to build a reputation as interpreters of Cuban music in various European locations. In the Autumn of 1934, the novelty of their performances had attracted film makers in Britain who engaged them 'to appear with Les Allen [a crooner] in the Gainsborough film The Code'. According to a report in the Melody Maker, 'Alex Kraut - the supreme novelty spotter of the recording business' became aware of the band's 'extraordinary cleverness'. He decided, therefore, 'to put them out on Regal-Zono[phone] introducing the new dance, the Conga'. (Regal-Zonophone was EMI's low-priced label, that had been launched after the Columbia-Gramophone merger).  These recordings comprised two 'Son Cubanos', a 'Son Rumba' and a 'Conga'.

These recordings comprised two 'Son Cubanos', a 'Son Rumba' and a 'Conga'. ![]() 26 The latter was Se Fue la Comparsa, the only Ernesto Lecuona composition of the four titles (Regal-Zonophone MR 1513). In addition to making the records (on 11 November) and presumably appearing in 'The Code', the Lecuona Cuban Boys played a 'highly successful fortnight' at the Alhambra. They then went to Paris to appear at the reopening of the 'Empire Theatre'.

26 The latter was Se Fue la Comparsa, the only Ernesto Lecuona composition of the four titles (Regal-Zonophone MR 1513). In addition to making the records (on 11 November) and presumably appearing in 'The Code', the Lecuona Cuban Boys played a 'highly successful fortnight' at the Alhambra. They then went to Paris to appear at the reopening of the 'Empire Theatre'. ![]() 27 From this point, the band took Paris by storm. In addition, the impression they created in London played a significant part in raising the status of Cuban music in Britain.

27 From this point, the band took Paris by storm. In addition, the impression they created in London played a significant part in raising the status of Cuban music in Britain.

Earlier in 1934, on 27 June, two Trinidad recording artists of long standing had arrived at Southampton. These were Lionel Belasco and Sam Manning. They had travelled from New York City on the White Star liner Majestic. Just over one month following their arrival Belasco had assembled an orchestra of local black musicians and, together, they recorded a session for UK Decca on 9 August. Manning sang on four of the 12 titles. There were two 'Fox Trots', four 'Rhumbas', a 'Rhumba Danza', a 'Rhumba Paseo' and four 'Valses'. All were issued in Decca's export series (Decca F 40443 - F 40448). With titles in Spanish and English, it seems that these pieces were aimed at the growing market for Latin American music. Manning's vocals, however, were in English. ![]() 28

28

On the evidence of one record (Imperial-Broadcast ME 101), Belasco organised a similar session for this label. For the occasion he used Juan Harrison as vocalist on Habanerita (a rumba that had been sung by Manning at the Decca recording date). ![]() 29 The presence of Harrison may suggest that the band used by Belasco was the 'All British Coloured Band' or 'Rumba Coloured Orchestra' organised in Britain by Rudolph Dunbar. This was active between 1932 and 1935 and, in 1934, featured Harrison as one of the vocalists. A clarinet player, Dunbar had trained in Guyana (his place of birth), the USA and France. After settling in France in 1925 he visited Britain as a member of various bands, but did not move to the United Kingdom until 1931. 'Rudolph Dunbar and his African Polyphony' accompanied vocalist Gladys Keep in two jazz sides recorded by Regal-Zonophone on 7 December 1934 (Regal·Zonophone MR 1531).

29 The presence of Harrison may suggest that the band used by Belasco was the 'All British Coloured Band' or 'Rumba Coloured Orchestra' organised in Britain by Rudolph Dunbar. This was active between 1932 and 1935 and, in 1934, featured Harrison as one of the vocalists. A clarinet player, Dunbar had trained in Guyana (his place of birth), the USA and France. After settling in France in 1925 he visited Britain as a member of various bands, but did not move to the United Kingdom until 1931. 'Rudolph Dunbar and his African Polyphony' accompanied vocalist Gladys Keep in two jazz sides recorded by Regal-Zonophone on 7 December 1934 (Regal·Zonophone MR 1531). ![]() 30

30

Black music from North America showed its influence in other ways. For instance, Sam Manning toured the country with a vaudeville show called 'Harlem Nightbirds'. This was first presented at the Queen's, Poplar at the end of September 1934. He appeared as a comedian. By the spring of the following year, his presence on the show had attracted the attention of a British-based reporter for the Sunday Guardian in Trinidad (17 March 1935). Alongside 'jazz themes', the paper noted the inclusion of calypsoes' (from Trinidad) and 'African rhythm' in an entertainment that employed 'singers and actors from Liverpool, Cardiff and the West Indies'. The show was identified as 'the first British Negro review'. Last reports traced for this endeavour are a week at the Blackburn Grand, beginning 27 May 1935. ![]() 31

31

Through his appearance in 'Harlem Nightbirds' (in which he also had a hand in the production), Manning had made contact with many black performers in Britain. Almost certainly these included the musicians he employed as his 'West Indian Rhythm Boys' in two sessions he cut for Parlophone in London on 18 and 24 July 1935. There were four sides. Two were 'West Indian Negro Spirituals', one was a 'pasea' (probably 'paseo') and the other was not given a rhythm description. This was Sweet Willie (Parlophone E 4110), which Manning later described as a 'St. Lucian Biguine'. The accompaniment reflected both black music from North America and Hawaiian guitar patterns. Sam Manning had first recorded this piece for OKeh in New York in 1925 and the earlier performance is one that had been issued in Britain three years later (Parlophone R 3851).

The other side of Manning's 1935 version of Sweet Willie was entitled Ara Dada (pasea) - sung by Gus Newton, a percussionist who had played with Rudolph Dunbar's band. The song had similar swinging accompaniment and was also performed in a style similar to Hawaiian music. The lyrics appear to have been in Trinidad Hindi (reflecting the East Indian-American population in the island). To confuse matters further, the title of the song might also be connected with Rada, the name used by African-Americans conscious of their Dahomian ancestry. Rada was also an African-American religious cult in Trinidad. The Venezuelan paseo is a dance tempo designated on many early calypso records.

Factors such as these demonstrate the complex development of African- American music in the English-speaking West Indies. During the 1930s, however, it was often jazz that provided a means of employment for black musicians from the West Indies domiciled in Britain. In this respect, Leslie Thompson, the Jamaican trumpet player who settled in Britain in 1929, was one of several performers who came together during late 1935 and early 1936. The result was the formation of a band to play contemporary US black swing music. Other musicians initially involved in this idea were Cyril and Happy Blake (brothers from Trinidad, who had been in Europe since the early 1920s).

Under the guidance of Leslie Thompson, the band (called the 'Aristocrats' or 'Emperors of Jazz') made its first appearance at the Troxy cinema, Stepney, London, on 26 April 1936. By mid 1937, this aggregation had come under the leadership of the Guyanese dancer Ken 'Snakehips' Johnson. His dancing had been a feature of the band's original programmes. Schooled in England, Johnson had spent 1935 in the Eastern Caribbean and the USA gaining experience and making contacts. ![]() 32 In late 1936 he arranged for Wally Bowen, a trumpeter from Guyana, to become a member of the band. Bowen arrived in December. In May 1937 he was joined by four musicians from Trinidad whom Johnson had met whilst he was in the Caribbean. These were Carl Barriteau, George Roberts, and Dave Williams (who played reed instruments) and the trumpeter Dave Wilkins (originally from Barbados).

32 In late 1936 he arranged for Wally Bowen, a trumpeter from Guyana, to become a member of the band. Bowen arrived in December. In May 1937 he was joined by four musicians from Trinidad whom Johnson had met whilst he was in the Caribbean. These were Carl Barriteau, George Roberts, and Dave Williams (who played reed instruments) and the trumpeter Dave Wilkins (originally from Barbados). ![]() 33 This encouraged black musicians from the Eastern Caribbean to travel to Britain in search of employment. Later in the year Edmundo Ross (later Ros) and Freddy Grant both made the journey to the United Kingdom.

33 This encouraged black musicians from the Eastern Caribbean to travel to Britain in search of employment. Later in the year Edmundo Ross (later Ros) and Freddy Grant both made the journey to the United Kingdom. ![]() 34 Others were to follow. Many of these performers received their training from military or police bands in the Caribbean. They proved capable of playing in several styles of African-American music. Those who remained with Ken Johnson played contemporary popular dance music and jazz. Johnson's West Indian Dance Orchestra made their first recordings in this style for British Decca in September 1938.

34 Others were to follow. Many of these performers received their training from military or police bands in the Caribbean. They proved capable of playing in several styles of African-American music. Those who remained with Ken Johnson played contemporary popular dance music and jazz. Johnson's West Indian Dance Orchestra made their first recordings in this style for British Decca in September 1938. ![]() 35 Other performers, like Edmundo Ros, concentrated on Latin American music.

35 Other performers, like Edmundo Ros, concentrated on Latin American music.

The popularity of the latter was fuelled by the continuing success of Cuban bands based in France. The Lecuona Cuban Boys, for example, made numerous recordings for French Columbia in this period. These were sold in Britain and in places as far afield as Finland and Turkey. The band also recorded sessions for Columbia in Britain, in November 1936 and October 1938. These took place during visits to London for performing engagements.

In the same period rumbas sustained their popularity in Africa. In South Africa, for example, a Singer catalogue from c. 1937 advertises 'Bantu Records: Including Africa's Newest! Red Hot Zulu RUMBAS!!' These were performed by the 'Royal Amanzimtoti Entertainers. Conductor William Mseleku'. The same catalogue also lists 'Rumbas' available on South African Brunswick. These included Paris recordings for British Decca by the Lecuona Cuban Boys, and Don Barreto. In addition, there were performances recorded by US Decca featuring the Cuban flautist Alfredo Brito, a tango coupling by José Ramos, plus The Rumba Dance by The Lion, a famous Trinidad songster, who cut this calypso in New York in 1936. The popularity of such recordings among black purchasers in South Africa is not known. ![]() 36

36

In Britain, the rising interest in Cuban music had persuaded the pianist Don Marino Barreto to settle in London and organise a Cuban Orchestra. He appears to have arrived late in 1937, when he recorded two sides for Parlophone that do not seem to have been released. He employed English-speaking West Indians in his band, one of who was Edmundo Ros. After his arrival in the United Kingdom Ros claimed he was from Venezuela, but his grandmother had brought him up in Belmont (a suburb of Port-of-Spain, Trinidad). He is reported to have been a member of the Trinidad Police Band in which he was employed as a percussionist. ![]() 37 Venezuela is separated from Trinidad by the Gulf of Paria, and is but five miles distant from the island. Ros undoubtedly spent some time on the South American mainland. He was able to speak Spanish as well as English.

37 Venezuela is separated from Trinidad by the Gulf of Paria, and is but five miles distant from the island. Ros undoubtedly spent some time on the South American mainland. He was able to speak Spanish as well as English.

Edmundo Ros probably joined forces with Don Marino Barreto during 1938 (they played together at the Embassy Club). He was employed as a percussionist and vocalist. When Marino Barreto cut his first session for Decca in London on 12 April 1939, Ros was the singer on the 'Comedy Rumba' El Sombrero de Gaspar (Decca F 7091). ![]() 38

38

Musicians such as Don Marino Barreto might specialise in a particular style, but they also found employment playing different kinds of American music. Just under one month after the session with 'his Cuban Orchestra', Marino Barreto recorded a two-part version of George Gershwin's Rhapsody In Blue for the same company (Decca F 7214). Other black musicians from the West Indies who worked in Europe between the two World Wars shared this versatility. In August 1938, Edmundo Ros and the Barbados trumpet player Dave Wilkins had been members of the 'Continental Rhythm', who accompanied the black US jazz pianist Fats Waller in a session recorded by HMV in London. ![]() 39

39

The advent of the Second World War in Europe on 3 September 1939 heralded circumstances that would alter the way in which the record business was organised in Europe and the United States. With this in mind, it is useful to divide the trends in recording that have been investigated into two phases of commercial operation - 1920 to 1930, and 1930 to 1940.

The principal manufacturers of gramophone records in Europe and the United States held a virtual monopoly. While smaller companies in the same line of business might trade alongside them, hardly any were in a position to challenge the large organisations. The latter consolidated themselves by absorbing rival companies that might threaten their position. The only exception to this was the reconstituted Decca Gramophone Company in Britain. Between 1930 and 1940, Decca established itself by a series of acquisitions and alliances (such as that with Brunswick Gramophone House in South Africa). In 1934, Decca seized the opportunity to launch a US company with the same name. This was able to compete with RCA Victor and Columbia (or, rather, the American Record Corporation, which had obtained the interests of the latter company). ![]() 40

40

It has been shown that between 1920 and 1930, the Gramophone Company continued its policy of opening up and establishing export markets for gramophones and gramophone records. For West Africa, there do not appear to have been any location recordings in this period. None were made in South Africa. That there were people interested in buying records of local music in these regions is evident from the activities of the Zonophone label. In general, the Gramophone Company used its operation in India to penetrate markets in East Africa. Recordings in Swahili were first advertised in 1914 but further information on these undertakings has not been located.

The year 1930 can be viewed as a fulcrum for the two phases of activity under consideration. Key events in West Africa were the demise of the Zonophone EZ series, and the advent of location recordings. In South Africa, the success of the recordings by Caluza's Double Quartet, and the launch by Singer of their new line in black music, were of similar importance. In the United States, the success of Cuban music in the domestic market was to instigate new trends in both Europe and Africa.

Throughout the 1930s, there were subtle changes in the way in which markets developed for local music in Africa and West Indian music in Europe (and Africa). Cuba provided the principal link in this respect, but the influence of Trinidad calypso in West Africa is sometimes assumed to have begun before this decade. The evidence of music recorded by the West African Instrumental Quintet in London in 1929 tends to support this assumption.

In this second phase of commercial endeavour, Cuban music in Europe appealed to many people across the continent. The style thereby became an international music alongside jazz from the USA. Unlike the success of the biguine from Martinique in France, in Britain there was little or no interest in vernacular music from the English-speaking West Indies. Virtually all the recordings made by Lionel Belasco in London in 1934 were released only for export. Sam Manning's Parlophone records (from both 1927 and 1935) remain little known. An attempt by British Decca to launch authentic calypsos from the US Decca Catalogue in 1938 met with indifference. Black West Indian musicians working in London, therefore, found employment playing popular styles from the USA and Cuba. Ken 'Snakehips' Johnson established himself as leader of a 'West Indian Dance Orchestra' (which also played jazz) and Edmundo Ros took up Cuban music. Unlike musicians from Martinique in Paris, or those from Cuba, in both Paris and London, neither made their careers as recording artists during the 1930s. After their session for Decca in 1938, Johnson's band did not record again until 1940. Ros formed his own 'Rumba Band' in 1940, but did not make records until 1941. These developments are outside the scope of this treatment. ![]() 41

41

Excepting the exotic appeal of music from Cuba, repertoire performed by musicians from Africa and the West Indies in Britain appears to have had little impact in the UK. Their popularity was much greater in other territories. This widespread dissemination of particular kinds of music by British gramophone record companies is under-recognised. They reaped large financial rewards from this enterprise and their overseas ventures are a prime measurement of their commercial achievements in this era.

© John H Cowley - 29.11.99

Alain Boulanger, in Paris, has sent essential pieces of information that have made this analysis more complete that it could have been otherwise.

Frank Andrews has been especially helpful with discographical conundrums. Brian Rust has also freely shared his discographical knowledge. Paul Vernon has added much needed extra particulars. Dick Spottswood has done likewise.

Michael Kinnear advised the date of the first East African recordings in the Gramophone Company's Indian catalogues. Much of this work could not have been undertaken without the free exchange of information between Howard Rye and myself. Bruce Bastin has been similarly unstinting.

Scott Hastie kindly read the manuscript. I am grateful to all these and others who have helped. Needless to say, all views expressed are my own.

Extracts from Crown Copyright Records in the Public Record Office appear by permission.

| Au Bal Antillais: Franco Creole Biguines from Martinique | Folklyric CD 7013 |

| Caluza's Double Quartet: 1930 | Heritage HT CD 19 |

| Domingo Justus: Roots of Juju, 1928 | Heritage HT CD 18 |

| Don Azpiazu Havana Casino Orchestra | Music Memoria 30911 |

| Don Barreto et son orchestre Cubain du Melody's Bar: 1932-1937 | Music Memoria 30993 |

| Edmundo Ros and His Rumba Band: 1939-1942 | Harlequin HQ CD 15 |

| George Williams Aingo: Roots of Highlife, 1927 | Heritage HT CD 17 |

| Ernesto Lecuona & The Lecuona Cuban Boys: 1932-1936, Vol. 4 | Harlequin HQ CD 26 |

| Rico's Creole Band | Harlequin HQ CD 31 |

| The West African Instrumental Quintet: 1929 | Heritage HT CD 16 |

Article MT113

| Top of page | Articles | Home Page | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |