One of the highlights of my musical upbringing was to hear the old Folkways Anthology of Folk Music set of recordings when I was about 15 or 16 years old.

One of the highlights of my musical upbringing was to hear the old Folkways Anthology of Folk Music set of recordings when I was about 15 or 16 years old.[Early Influences:] [Popular & Parlour Songs and Ballads] [Blues] [Topical Songs] [Religious Songs]

[3. Conclusions] [Acknowledgements:] [Notes:]

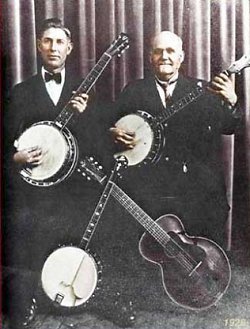

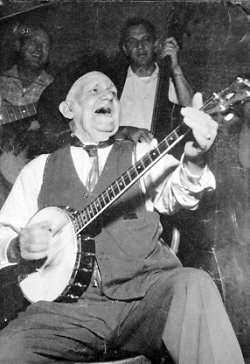

“And now Friends we present Uncle Dave Macon, with his gold teeth, plug hat, chin whiskers, gates-ajar collar and that million dollar Tennessee smile ... take it away Uncle Dave!” - George D Hay, the ‘Solemn Old Judge’ in the 1940 Republic Picture: Grand Ole Opry

One of the highlights of my musical upbringing was to hear the old Folkways Anthology of Folk Music set of recordings when I was about 15 or 16 years old.

One of the highlights of my musical upbringing was to hear the old Folkways Anthology of Folk Music set of recordings when I was about 15 or 16 years old.![]() 1 The number of singers and musicians that I heard there was just breathtaking, although, for me, one performer stood out from all the rest - Uncle Dave Macon, singing two songs Way Down the Old Plank Road and Buddy Won’t You Roll Down the Line. Now, fifty years later, I still believe that Uncle Dave was one of the greatest of all the Old-Timey singers and musicians that ever recorded. In fact, I would say that some of his recordings, especially those made with The Fruit Jar Drinkers, are possibly the best examples of Old-Timey music ever made. Over the years I must have heard just about all of his issued recordings and each new experience has brought a tingle down my spine. Uncle Dave had one of the largest repertoires of any of the early recording stars. The bulk of his recordings were of late 19th century/early 20th century songs (most with known composers). He also recorded religious pieces, together with some American folk and topical songs. But, unlike, say, the Carter Family or Charlie Poole, I did not hear any Anglo-American folksongs, and this is something that has puzzled me over the years. (In fact, as we shall see later, Uncle Dave did record a couple of Anglo-American songs, but, as these were unissued, there was never any chance of me hearing them!) In a way, this piece is my tribute to Uncle Dave. It is also a massive “Thank You” to him and to all the other musicians who played along and recorded with him.

1 The number of singers and musicians that I heard there was just breathtaking, although, for me, one performer stood out from all the rest - Uncle Dave Macon, singing two songs Way Down the Old Plank Road and Buddy Won’t You Roll Down the Line. Now, fifty years later, I still believe that Uncle Dave was one of the greatest of all the Old-Timey singers and musicians that ever recorded. In fact, I would say that some of his recordings, especially those made with The Fruit Jar Drinkers, are possibly the best examples of Old-Timey music ever made. Over the years I must have heard just about all of his issued recordings and each new experience has brought a tingle down my spine. Uncle Dave had one of the largest repertoires of any of the early recording stars. The bulk of his recordings were of late 19th century/early 20th century songs (most with known composers). He also recorded religious pieces, together with some American folk and topical songs. But, unlike, say, the Carter Family or Charlie Poole, I did not hear any Anglo-American folksongs, and this is something that has puzzled me over the years. (In fact, as we shall see later, Uncle Dave did record a couple of Anglo-American songs, but, as these were unissued, there was never any chance of me hearing them!) In a way, this piece is my tribute to Uncle Dave. It is also a massive “Thank You” to him and to all the other musicians who played along and recorded with him.

1. Uncle Dave

David Harrison Macon was born five years after the ending of the American Civil War, on October 7th, 1870, in Smart Station, a small settlement close to McMinnville, Tennessee. His father, Captain John Macon, had been an officer in the Confederate Army. His mother was Martha Ramsey Macon. Thirteen years later David’s father bought the Old Broadway Hotel in Nashville, a hotel used by travelling vaudeville artists and circus performer. The family also lived in the hotel and the young David found himself surrounded by all kinds of performers and musicians. In 1885 a circus comedian called Joel Davidson, who worked for Sam McFlynn’s circus, taught David to play the 5-string banjo. However, in 1886 David’s father was murdered in a fight at the hotel. Some reports say that David witnessed the killing, but other accounts say that it was his mother who was present at the event. The tragedy was such that Martha Macon promptly sold the hotel and moved her family to Readyville, TN, ten miles south of Murfreesboro, where she ran a stagecoach stop. David, in order to earn some small change, apparently began entertaining the coach passengers by playing his banjo on a small stage that he had constructed himself.

David Macon was nineteen years old when he married Matilda Richardson. The couple bought a farm at Kittrel, TN, where David also formed the Macon Midway Mitchell Mule and Wagon Transportation Company, a one-man operation run by David to haul merchandise between the towns of Woodbury and Murfreesboro. Apparently, there were four grocery stores around a square in Murfreesboro and David would sing out as he pulled up with his deliveries outside each store. Once the delivery work was finished, David would head for home down the Main Street playing his banjo and singing as he left town, much to the delight of the town’s children. In fact, David Macon spent some twenty years hauling goods around Murfeesboro before he was forced out of work by the arrival of cars and trucks.

Things were not looking too good for David, but, sometime around 1922, he was invited to sing at a Shriner’s meeting. By chance, he was spotted by Marcus Loew of Loews Theatres who offered him a chance to perform for a night at a Loew’s Theatre in Alabama. David accepted and travelled to Alabama with a friend, Fiddlin’ Sid Harkreader, whom he had met previously while playing at Charlie Melton’s barbershop in Nashville. Harkreader just happened to walk into the barber shop with his fiddle under his arm and started to play alongside Macon’s banjo. The pair became good friends. Macon so impressed Marcus Lowe that he offered the pair a week’s contract to perform at his theatre in Birmingham, Alabama, apparently for several hundred dollars. In fact, Macon & Harkreader were so popular with the Birmingham audiences that their contract was extended to a month, before they were invited to tour at other Loew’s theatres. This, we may say, was the start of David Macon’s professional career as a singer and musician. There were to be many other offers from different theaters in the Loew’s vaudeville circuit and, on one occasion, a rival circuit, the Keith-Albee-Orpheum Corporation, tried to poach Uncle Dave (as he was now being called) away from Marcus Loew, but to no avail.

It is, I think, important to say a little here about Sidney 'Sid' J Harkreader (1898 - 1988) a musician who appeared on many of David Macon’s best recordings and who was probably influential in helping David choose which songs and tunes the pair should record. Harkreader came from a farm in Wilson County, TN. Surprisingly, none of his immediate family played fiddle, although a great-grandfather was well-known as a violinist. It seems that he learnt to play fiddle from a neighbour and also from an elderly man who worked on his father’s farm. He also played guitar and was known locally as a singer. By 1924, Sid and Uncle Dave had come to the notice of James Gilbert Sterchi of the Sterchi Brothers Furniture Company of Knoxville, TN. As well as selling furniture, including phonograph players, Sterchi also acted as an agent for Vocalion Records, both by selling and distribution the records and also by acting as a talent scout for the Company. In fact it was Sterchi who recommended that Uncle Dave and Sid Harkreader should be recorded and who also provided the necessary funds to pay for their trip to New York, where Vocalion had their recording studios. According to the American folklorist Archie Green, Macon’s version of Hesitation Blues, recorded on that trip under the title of Hill Billie Blues, was one reason why the word 'hillbilly' entered the American language, especially when associated with Country music.

Over the years Uncle Dave had picked up a number of tricks while playing his banjo. He would swing the banjo out in front of his body, holding it by the neck with his left hand, and somehow managing to keep the tune going at the same time! He would fan the strings with his hat, or else play the instrument whilst holding it between his legs.

He would also shout out between singing, using phrases such as “Hot dog”, or else “Kill yourself”, and, all the time, he would stomp his feet on the floor creating a rhythm that just drove his songs and tunes forward. He was, without doubt, unique within the field of American music, and the public just loved him. Often, Uncle Dave would add spoken comments to his recordings. The term 'PC' was not around when Uncle Dave spoke the following introduction to his Sourwood Mountain Medley:

At one time in his career Uncle Dave worked in shows with the bluegrass musician Bill Monroe, who said that Uncle Dave would peep out of the curtains to see how many people were in the audience. If the house was full, Uncle Dave would tell Monroe, “Looks like Uncle Dave can still draw them in.” But if the audience was sparse he would say, “Mr Bill, you can’t draw them like you used to!”

In 1925 “Dancing Bob” Bradford, a buck-dancer joined Uncle Dave and Sid Harkreader as part of their Loew’s act. It was also in 1925 that Uncle Dave first began playing regularly with the singer and guitarist Sam McGee. The pair had first met the previous year, when Uncle Dave and Sid Harkreader were playing at a show near Franklin, TN. Sam invited Uncle Dave home after the show and, having performed a version of the Missouri Waltz, was asked by Uncle Dave to join him and Sid Harkreader as part of their act. The three first appeared, along with 'Dancing Bob' Bradford, at Loew’s Bijou Theatre in Birmingham, Alabama. Later that years Sam’s brother, the guitarist Kirk McGee, also started performing with Uncle Dave and Sam, the trio using the stage name of 'Uncle Dave Macon and his Sons from Billygoat Hill'. Sam McGee was a brilliant instrumentalist and, although Uncle Dave did win prizes at banjo competitions, was probably the better player of the two. He once said of Uncle Dave, “I never did learn much about playing from him. But I did learn about handling an audience.”

On 6th November, 1925, Uncle Dave and Sid Harkreader were asked by the Nashville Police Force to perform at the Ryman Auditorium, a building that was to become synonymous with Old-Timey and Country Music, because it was to become the home of the Grand Old Opry, a Saturday night concert that was transmitted by radio throughout the American South. Uncle Dave was one of the first artists to be invited onto the Opry show and he remained there almost up to the time of his death in 1952. Sam and Kirk McGee were also popular players on the Opry. As Sam used to say, “The Opry came down here and said they wanted players who were outstanding in the field - and that’s where they found us, out standing in the field.” On a more serious note, Sam said, “Just as soon as word circulated about the Opry, the Barn Dance as it was then, everybody got excited about it. Uncle Dave Macon and me were down in Alabama. He says, ‘Let’s go and play on that Barn Dance.’ It wasn’t any trouble to get on then because it was so new and they didn’t have the people they needed.”

It seems likely that the Opry listeners were only too happy to buy Uncle Dave’s recordings, which sold so well that he was constantly invited back into various recording company studios. In fact, Uncle Dave was recorded every year between1924 and 1930, and was also in the studio in 1934, 1935, 1937 and 1938. During this period he cut a total of 216 sides, 40 of which were rejected, leaving a total of 176 issued sides. Quite why 40 sides were rejected remains something of a mystery, because three masters - for Oh Lovin Babe, Come On Buddie, Don’t You Want to Go and Go On, Nora Lee - were traced and reissued on a Rounder LP, and all three songs are as good as anything else that Uncle Dave recorded.![]() 5 Another unissued track - Tennessee Tornado - has also turned up, as a test-pressing with Uncle Dave’s handwriting on the label. It was unearthed in a garage sale in Murfreesboro.

5 Another unissued track - Tennessee Tornado - has also turned up, as a test-pressing with Uncle Dave’s handwriting on the label. It was unearthed in a garage sale in Murfreesboro.![]() 6

6

Over a four day period in 1927, Uncle Dave recorded a total of 38 sides in New York City for the Vocalion Record Company. There were eight solo tracks (banjo and voice), two tracks with Sam and Kirk McGee and a further twenty-eight tracks by Uncle Dave, the McGee Brothers and fiddler, Mazy Todd. Eighteen of these tracks were issued as by “Uncle Dave Macon & His Fruit Jar Drinkers”, the rest as by the “Dixie Sacred Singers”, or else as “Uncle Dave Macon & McGee Brothers”, when Mazy Todd was not playing. As I said above, the tracks by “Uncle Dave Macon & His Fruit Jar Drinkers” are some of the greatest ever recorded and include such classics as Bake that Chicken Pie, Rock About My Sara Jane, Tell Her to Come Back Home, Hold That Wood-Pile Down, Carve that Possum, Sail Away, Ladies, The Grey Cat on the Tennessee Farm, I’se Gwine Back to Dixie, Tom and Jerry, The Rabbit in the Pea Patch and Jordan is a Hard Road to Travel.![]() 7

7

In June, 1929, Uncle Dave and Sid Harkreader cut a further 18 tracks, though only six were actually issued and it may be that the economic situation was forcing record companies to cut back on their issues. Nine months later, on 31st March, 1930, Uncle Dave and his son Doris recorded eight sides for Brunswick Records, Uncle Dave having by then partially parted with the McGee Brothers. All of these sides were rejected.

In June, 1929, Uncle Dave and Sid Harkreader cut a further 18 tracks, though only six were actually issued and it may be that the economic situation was forcing record companies to cut back on their issues. Nine months later, on 31st March, 1930, Uncle Dave and his son Doris recorded eight sides for Brunswick Records, Uncle Dave having by then partially parted with the McGee Brothers. All of these sides were rejected.![]() 8

8

By 1935 the Depression years were beginning to be overtaken by a new optimism and Uncle Dave signed up with Bluebird Records who, in four sessions, recorded a total of 29 songs. The first session was made with the Delmore Brothers. The next, in 1937, had Uncle Dave playing with an unknown fiddler and unknown guitarist on some tracks. Finally, there were two sessions held in 1938, the first with “Smokey Mountain” Glen Stagner joining in on some tracks, the second with an unknown fiddler on some tracks.

Although Uncle Dave made no more commercial recordings after 1938, he did continue to tour and appear on the Grand Old Opry. In fact, he had appeared on the latter only three weeks before he died, on 22nd March, 1952, eighty-one years young, in a Murfreesboro hospital. According to the locals, all the roads around Murfreesboro were gridlocked as people tried to get to Coleman’s Cemetry for the graveside service.

Cap'n Tom Ryman was a steamboat man,

But Sam Jones sent him to the heavenly land,

Oh, sail away

Oh, there's nothing to do but to sit down and sing

Oh, rockabout my Saro Jane, oh rockabout my Saro Jane,

Oh, rockabout my Saro Jane

Oh, rockabout my Saro Jane

Oh, rockabout my Saro Jane

Oh, there's nothing to do but to sit down and sing

Oh, rockabout my Saro Jane

Engine give a scratch and the whistle gave a squall

The engineer going to a hole in the wall,

Oh, Saro Jane

There's nothing to do but to sit down and sing

Oh, rockabout my Saro Jane

I said at the beginning of this article that I had not heard any Anglo-American songs sung by Uncle Dave. In fact, Uncle Dave did record two such pieces. On 21st June, 1926, he recorded a version of the song Darby Ram (Roud 126) and on 31st March, 1930, a version of the children’s song Little Sally Waters (Roud 4509). Both recordings, however, remain unissued. Uncle Dave, unlike, say, The Carter Family, was not from the Appalachian Mountain region, where Anglo-American songs did survive. He was from Nashville, and the area around Nashville, where both Darby Ram and Little Sally Waters were known in both black and white American song traditions.![]() 12 Another such song is one titled Late Last Night When My Willie Came Home (Way Downtown) that Uncle Dave recorded in1926 with Sam McGee. It goes as follows:

12 Another such song is one titled Late Last Night When My Willie Came Home (Way Downtown) that Uncle Dave recorded in1926 with Sam McGee. It goes as follows:

This is Uncle Dave’s version:

Chorus:

Run nigger run the patroller will catch you,

Run nigger run its almost day.

Tell my mammy when I go home,

Girls won't let them boys alone.

Last year was a good crop year, roasting ears and tomatoes,

Poppa didn't raise no cotton and corn, but Lord, Lord, potatoes.

Tell my mammy when I go home,

Girls won't let them boys alone.

Adam and Eve was down in the garden hoeing around tomatoes,

Adam went around a huckleberry bush and hit her in the eye with a tater.

Tell my mammy when I go home,

Girls won't let them boys alone.

Jaybird built in the tall oak tree,

Sparrow built in the garden,

Old goose laid in the corner of the fence,

And set on the other side of Jordan.

Tell my mammy when I go home,

Girls won't let them boys alone.![]() 16

16

He also recorded a version of Stop Dat Knocking, a song popularized by the Christy Minstrels in the 1850s. The song was the work of A F Winnemore and was first published in 1847. Uncle Dave’s recording, made on the 8th September, 1926, was titled Stop That Knocking at My Door.![]() 20

20

Uncle Dave must have been feeling in a 'Minstrel mode' that day, because after recording Stop That Knocking at My Door he promptly recorded another Minstrel piece, Sassy Sam.![]() 21

21

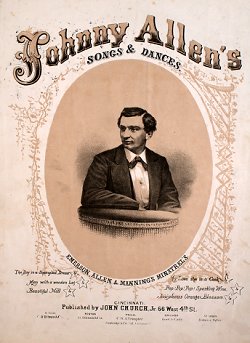

The song, written and composed by Ned Straight in 1868, was originally titled Josiphus Orange Blossom and was printed in Johnny Allen’s Songs and Dances. Straight’s original text is as follows:

My name it is Josiphus Orange Blossom,

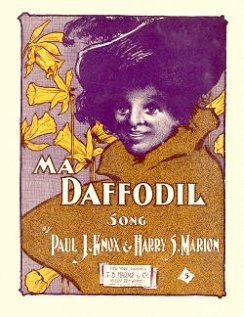

My name it is Josiphus Orange Blossom,  Another Minstrel Show song was I Don’t Care if I Never Wake Up, written by Paul J Knox in 1899. Knox wrote several Minstrel songs, including The Unlucky Coon and Every Darkey Had a Nervous Spell (no surprise, I guess, if they saw titles like that!). But, Knox also had a more tender side, as in his song Ma Daffodil, written in 1900.

Another Minstrel Show song was I Don’t Care if I Never Wake Up, written by Paul J Knox in 1899. Knox wrote several Minstrel songs, including The Unlucky Coon and Every Darkey Had a Nervous Spell (no surprise, I guess, if they saw titles like that!). But, Knox also had a more tender side, as in his song Ma Daffodil, written in 1900.

The sheet music cover depicts the image of a well-dressed African American and suggests that the song may have been marketed towards a black audience. It is certainly far more respectful than many sheet covers of that era. And, indeed, Knox’s words are also far more restrained than in, say, the song that Uncle Dave recorded, I Don’t Care if I Never Wake Up.![]() 22

22

Ma Daffodil opens with these lines:

Another similar song was Watermelon Smilin’ on the Vine, written by Thomas P Westendorf and published, in 1882, by The W F Shaw Publishing Co (Chicago & New York). Westendorf’s set is as follows:

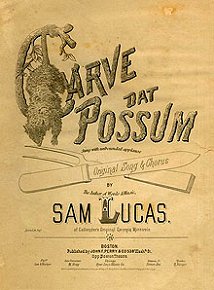

De possum meat am good to eat,

De possum meat am good to eat,

Carve him to de heart;

You'll always find him good and sweet,

Carve him to de heart;

My dog did bark, and I went to see,

Carve him to de heart;

And dar was a possum up dat tree,

Carve him to de heart.

Carve dat possum, carve dat possum, children,

Carve dat possum, carve him to de heart;

Oh, carve dat possum, carve dat possum, children,

Carve dat possum, carve him to de heart.

I reached up for to pull him in,

Carve him to de heart;

De possum he begun to grin,

Carve him to de heart;

I carried him home and dressed him off,

Carve him to de heart;

I hung him dat night in de frost,

Carve him to de heart.

De way to cook de possum sound,

Carve him to de heart;

Fust parbile him, den bake him brown,

Carve him to de heart;

Lay sweet potatoes in de pan,

Carve him to de heart;

De sweetest eatin' in de lan',

Carve him to de heart.

Another of Uncle Dave’s songs which incorporates 'floating verses' also contains another of his 'trade-marks', namely spoken passages interjected between the sung verses. The song is called Travelin’ Down the Road:

And this was not the only time that Uncle Dave would mix up all sorts of verses together. Take the song Walk, Tom Wilson, Walk:

If, as I said above, there is little evidence to suggest that Uncle Dave knew many Anglo-American folksongs, then we may also note that he recorded very few American folksongs. The Death of John Henry, printed above, is one such song. In 1929 Uncle Dave recorded a number of songs, including four pieces (each the side of a 78rpm record) which he titled Uncle Dave’s Travels - Parts 1 -4. Part 2 was sub-titled Around Louisville, Ky, part 3 was In and Around Nashville, while part 4 was titled Visit at the Old Maid’s.![]() 33 Surprisingly, part 1 was a complete version of the folksong Misery in Arkansas (Roud 257). It begins with a typical Uncle Dave device, a spoken dedication, this time to one of his old friends. As can be seen, Uncle Dave just loved playing with words.

33 Surprisingly, part 1 was a complete version of the folksong Misery in Arkansas (Roud 257). It begins with a typical Uncle Dave device, a spoken dedication, this time to one of his old friends. As can be seen, Uncle Dave just loved playing with words.

Uncle Dave was also aware of a number of a number of old fiddle & banjo tunes, such as Love Somebody, Soldier’s Joy, Muskrat, Rye Strawfields, Hop High Ladies, The Cake’s All Dough, Bile The Cabbage Down, The Girl I Left Behind Me, Whoop ‘Em Up Cindy, Devil’s Dream and Sourwood Mountain.![]() 35

35

I think it fair to say that, in general, we can only surmise about Uncle Dave’s early musical influences. He certainly knew quite a few early fiddle and banjo tunes and also knew some songs which, today, we would call folksongs. Many of the songs that appear to have come from black singers did, as we can clearly see, come from the pens of white composers, although, as in the case of Carve Dad Possum, Uncle Dave may have picked these up from oral, rather than printed sources. We also know that, in his recordings, Uncle Dave frequently mixed together lines and verses from different songs.

Popular & Parlour Songs and Ballads

When I first set out to write this article I began by trying to place Uncle Dave's songs into various categories - folksongs, negro-songs, blues, topical songs etc. - but it soon became apparent that this was not the right way to go about it. I say this, because many of the songs could easily fit into more than one category. You can see what I mean by looking at the song Down in Arkansas.![]() 36

36

It seems that the song was written in 1913 by one George 'Honey Boy' Edwards (1870 - 1915), a 'blackface' minstrel, who came originally from Wales. The song has also entered the 'tradition', in that Alan Lomax recorded a version of the song from the singer Almeda Riddle in 1959.

It seems that the song was written in 1913 by one George 'Honey Boy' Edwards (1870 - 1915), a 'blackface' minstrel, who came originally from Wales. The song has also entered the 'tradition', in that Alan Lomax recorded a version of the song from the singer Almeda Riddle in 1959.

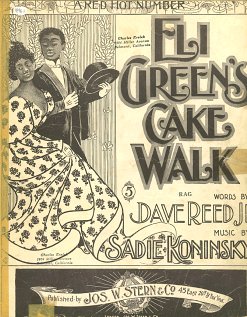

Or take the well-know Eli Green's Cakewalk, written by David Reed and Sadie Koninsky and first recorded in 1899 by the banjo player Vess Ossman on Edison Records. Uncle Dave recorded Eli Green's Cakewalk in 1929 for Brunswick Records, though the Company failed to issue the recording. Described as a 'red hot number' on the music sheets, the piece depicts a black couple stepping out to the tune. Reed & Koninsky were, of course, white composers.

Or take the well-know Eli Green's Cakewalk, written by David Reed and Sadie Koninsky and first recorded in 1899 by the banjo player Vess Ossman on Edison Records. Uncle Dave recorded Eli Green's Cakewalk in 1929 for Brunswick Records, though the Company failed to issue the recording. Described as a 'red hot number' on the music sheets, the piece depicts a black couple stepping out to the tune. Reed & Koninsky were, of course, white composers.

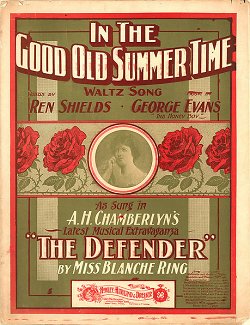

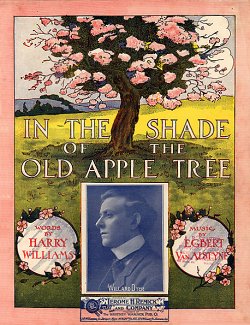

I would suggest that approximately 60 - 65 % of Uncle Dave's recorded repertoire is comprised of songs with known composers, ones that date from the latter half of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th. (Actually, the figure is higher if we include the Religious songs that Uncle Dave recorded). Some of these songs, such as The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane, Down By the Old Mill Stream, In the Good Old Summer Time and In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree are extremely well-known.![]() 38

38

Others are, perhaps less well-known. William J Scanlan's Peek-A-Boo was written in 1883, the same year that Barney Fagan composed Since Baby's Learned to Talk.

Others are, perhaps less well-known. William J Scanlan's Peek-A-Boo was written in 1883, the same year that Barney Fagan composed Since Baby's Learned to Talk.![]() 39 Scanlan was also the composer of another of Uncle Dave's well-known songs, Over the Mountain, written in 1882.

39 Scanlan was also the composer of another of Uncle Dave's well-known songs, Over the Mountain, written in 1882.![]() 40 Occasionally Uncle Dave would change titles (and, sometimes, the words). In 1869 C T Lockwood & J Wild composed And He's Got the Money Too, a song which Uncle Dave recorded as She's Got the Money Too in 1930, although he kept the composer's titles with songs such as Just Tell Them That You Saw Me, written by Paul Dresser in 1895, and When the Harvest Days are Over, written & composed by Howard Graham & Harry Von Tilzer in 1900.

40 Occasionally Uncle Dave would change titles (and, sometimes, the words). In 1869 C T Lockwood & J Wild composed And He's Got the Money Too, a song which Uncle Dave recorded as She's Got the Money Too in 1930, although he kept the composer's titles with songs such as Just Tell Them That You Saw Me, written by Paul Dresser in 1895, and When the Harvest Days are Over, written & composed by Howard Graham & Harry Von Tilzer in 1900.![]() 41

41

Another song written in 1900 was Cal Stewart's Ticklish Reuben, recorded in 1926 by Uncle Dave as Something's Always Sure to Tickle Me.![]() 42 The year 1900 must have been a good one for song-writers, because that was also the year when J Cheever Goodwin and Maurice Levi wrote When Reuben Came to Town, yet another of the songs that found their way into Uncle Dave's repertoire, as did the song I'll Never Go There Any More.

42 The year 1900 must have been a good one for song-writers, because that was also the year when J Cheever Goodwin and Maurice Levi wrote When Reuben Came to Town, yet another of the songs that found their way into Uncle Dave's repertoire, as did the song I'll Never Go There Any More.![]() 43

43

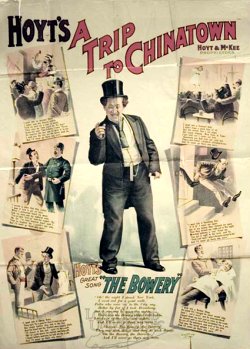

I'll Never Go There Any More was originally titled The Bowery and was the work of Charles H Hoyt and Percy Gaunt. It was written in 1891 for the successful Broadway play A Trip to Chinatown and, again, Uncle Dave had to omit some of the original text in order to fit the song onto one side of a 78rpm record.

|

The Bowery

by Charles H Hoyt and Percy Gaunt Oh! the night that I struck New York, I went out for a quiet walk; Folks who are 'on to' the city say, Better by far that I took Broadway; But I was out to enjoy the sights, There was the Bow'ry ablaze with lights; I had one of the devil's own nights! I'll never go there anymore. Refrain: The Bow'ry, the Bow'ry! They say such things, And they do strange things On the Bow'ry! The Bow'ry! I'll never go there anymore! I had walk'd but a block or two, When up came a fellow, and me he knew; Then a policeman came walking by, Chased him away, and I asked him why. 'Wasn't he pulling your leg?,' said he. Said I, 'He never laid hands on me!' 'Get off the Bow'ry, you Yap!,' said he. I'll never go there anymore. I went into an auction store, I never saw any thieves before; First he sold me a pair of socks, Then said he, 'How much for the box?' Someone said 'Two dollars!' I said 'Three!' He emptied the box and gave it to me. 'I sold you the box not the sox,' said he, I'll never go there any more. I went into a concert hall, I didn't have a good time at all; Just the minutes that I sat down Girls began singing, 'New Coon in Town,' I got up mad and spoke out free, 'Somebody put that man out,' said she; A man called a bouncer attended to me, I'll never go there anymore. I went into a barbershop, He talk'd till I thought that he'd never stop; I, cut it short, he misunderstood, Clipp'd down my hair just as close as he could. He shaved with a razor that scratched like a pin, Took off my whiskers and most of my chin; That was the worst scrape I'd ever been in. I'll never go there anymore. I struck a place that they called a 'dive,' I was in luck to get out alive; When the policeman heard of my woes, Saw my black eye and my batter'd nose, 'You've been held up!,' said the copper fly. 'No, sir! But I've been knock'd down,' said I; Then he laugh'd, tho' I could not see why! I'll never go there anymore! |

I'll Never Go There Any More

As sung by Uncle Dave Macon. Oh, the night that I struck New York, I went out for a quiet walk, Folks that long to the City say, Better by far that I had Broadway, But I was out to enjoy the sights, And there was the Bowery a blazed with lights, And I had one of those tough old nights, I'll never go there anymore. I went into a concert hall, I didn't have a good time at all, Just the minute that I sat down, Girls began singing 'New Coon in Town,' Got up mad and I spoke out free, 'Somebody put that man out cried she,' And a man called a bouncer attended to me, I'll never go there anymore. I went into a barbershop, He talked till I thought he would never stop, I cut it short, he misunderstood, Clipped down my hair just as close as he could, Shaved with a razor that scratched like a pin, Took off my whiskers and most of my chin, But that was the worst scrape I ever got in, I'll never go there anymore. I went into an auction store, I never saw any thieves before, First he showed me a pair of socks, Then said he, 'how much for the box?' Someone said two dollars, I said three, He emptied the box and he gave it to me, 'Sold you the box not the socks,'says he, I'll never go there anymore. I struck a place that they called, a dive, I was in luck to get out alive, When the policeman heard my woes, Saw my black eyes and my battered nose, 'You've been held up.'says the copper fly, 'No, sir, but I've been knocked down.'says I. Then he laughed, oh I couldn't see why, I'll never go there anymore. |

|

Clearly, much of Uncle Dave's repertoire had been published in the mid to late 1800s and the early part of the 1900s. But Uncle Dave did not necessarily restrict himself to older songs. He did, on occasion, also sing more recent compositions, such as Beautiful Love, which he recorded in 1938.![]() 44 The song had actually been written in 1931 by Wayne King, Victor Young, Egbert Van Alstyne and Haven Gillespie and was originally popularized by the Wayne King Orchestra.

44 The song had actually been written in 1931 by Wayne King, Victor Young, Egbert Van Alstyne and Haven Gillespie and was originally popularized by the Wayne King Orchestra.

Blues

It is sometimes said that the term 'blues', for a specific musical form, came into existence in 1912 when W C Handy composed and published the song Memphis Blues. Handy said that in1903, in Tutwiler, Mississippi, he first heard the blues being sung by a Negro. 'A lean loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept ... As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars ... The singer repeated the line three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard.'![]() 45 In fact, Memphis Blues was based on a campaign tune, Mr Crump, originally written in 1909 for Edward Crump, the successful Memphis mayorial candidate.

45 In fact, Memphis Blues was based on a campaign tune, Mr Crump, originally written in 1909 for Edward Crump, the successful Memphis mayorial candidate.![]() 46 Other writers have agreed with Handy that the blues began in the Mississippi Delta. See, for example, Alan Lomax's book The Land Where the Blues Began.

46 Other writers have agreed with Handy that the blues began in the Mississippi Delta. See, for example, Alan Lomax's book The Land Where the Blues Began.![]() 47 Others have been more specific, stating that the blues began on Will Dockery's Plantation, with singers such as Charlie Patton. I have also heard some Americans suggest that the blues actually began in the Piedmont region of the Eastern States. One English enthusuast has shown that the words to a number of British Music Hall songs can be found in early blues recordings and a recent book gives us details of the musical term 'blues' being used well before W C Handy pegged the word.

47 Others have been more specific, stating that the blues began on Will Dockery's Plantation, with singers such as Charlie Patton. I have also heard some Americans suggest that the blues actually began in the Piedmont region of the Eastern States. One English enthusuast has shown that the words to a number of British Music Hall songs can be found in early blues recordings and a recent book gives us details of the musical term 'blues' being used well before W C Handy pegged the word.![]() 48 For example, in 1871 A A Chapman published the song Oh, Ain't I Got the Blues while, in 1872, Harry Linn and Rollin Howard produced a song with the title You Never Miss Yor Water Till the Well Runs Dry, a line which turns up in several later blues. If this all sounds a little complicated, well, it is! When we say 'blues' we usually mean a 12-bar verse of three lines, in AAB format. But this is not always the case, especially when we look at the six 'blues' that Uncle Dave recorded.

48 For example, in 1871 A A Chapman published the song Oh, Ain't I Got the Blues while, in 1872, Harry Linn and Rollin Howard produced a song with the title You Never Miss Yor Water Till the Well Runs Dry, a line which turns up in several later blues. If this all sounds a little complicated, well, it is! When we say 'blues' we usually mean a 12-bar verse of three lines, in AAB format. But this is not always the case, especially when we look at the six 'blues' that Uncle Dave recorded.

On 17th February, 1927, Bessie Smith recored a version of the song Backwater Blues. The text went like this.

I woke up this mornin', can't even get out of my door

I woke up this mornin', can't even get out of my door

There's been enough trouble to make a poor girl wonder where she want to go

Then they rowed a little boat about five miles 'cross the pond

Then they rowed a little boat about five miles 'cross the pond

I packed all my clothes, throwed them in and they rowed me along

When it thunders and lightnin' and when the wind begins to blow

When it thunders and lightnin' and the wind begins to blow

There's thousands of people ain't got no place to go

Then I went and stood upon some high old lonesome hill

Then I went and stood upon some high old lonesome hill

Then looked down on the house were I used to live

Backwater blues done call me to pack my things and go

Backwater blues done call me to pack my things and go

'Cause my house fell down and I can't live there no more

Mmm, I can't move no more

Mmm, I can't move no more

There ain't no place for a poor old girl to go.![]() 49

49

Instrumental break (Wreck of Old 97)

Spoken: Hot dog! I'm old but I'm round here!

Backwater's up and the people are runnin'

I'm a-goin' to the mountain, I'm a-goin' huntin'

Fare you well, oh my little darlin'

Lord, lord, ain't I gone

Oh my love, lonesome road

Oh my love, lonesome wood

I love you and you can't help it

You love me, but you won't confess it

No you don't, oh my little darlin'

Lord, lord, ain't I gone

Oh my love, lonesome road

Oh my love, lonesome wood

Two little children lyin' in the bed

The water was a-risin' over their head

Their mother's up town, was never found

Lord, lord, wasn't that sad

Oh how bad, oh how sad

I heard a man talkin' to a feller

The water was a-risin' in his cellar

Rise any more and a-comin' through the floor

Lord, lord, open the door

Oh my love, lonesome road

Oh my love, lonesome wood

Nashville is a favourite town

The back water's got us a-runnin' around

Lord have mercy, ain't I gone

Lord, lord, fare you well

Oh my love, lonesome road

Oh my love, lonesome wood.![]() 50

50

In fact, Uncle Dave recorded a total of six songs with the word 'blues' in the title. As well as Backwater Blues, there were Hill Billie Blues, Arcade Blues, Heartaching Blues, All In Down and Out Blues and The Mourning Blues (or should that be Morning Blues?) and none, strictly speaking is really a 'blues'.![]() 51 Two of these, Hill Billie Blues and The Mourning Blues are actually based on a song, Hesitating Blues, that W C Handy copywrited in 1912.

51 Two of these, Hill Billie Blues and The Mourning Blues are actually based on a song, Hesitating Blues, that W C Handy copywrited in 1912.

I am Billie and I live in the hills,

I can whistle and sing like a Whippoorwill,

Come across the mountain, just down in the holler,

To see my little Dony, just as sweet as she can waller.

Chorus:

Oh, tell me how long, must I wait?

Lord, I get you now, or Lord I hesitate.

Hello sig, what's the matter with the line,

I can't talk to that girl of mine,

Storm last night blew all the poles down,

I can't talk to my Saro Brown.

As long as a bacon is thirty cents a pound,

I'm going to eat a rabbit if I have to run him down,

Ice cream cone, T-bone steak,

You want to win a women get a Cadillac eight.

I been in the city and I been in the town,

I been in the mountains with the blues falling down,

Jumped in the river and I thought I would drown,

I spied a redheaded woman and I couldn't go down.

Whiskey, whiskey, I'm going to let you be,

The bone dry law made a Christian out of me,

Going to Oklahoma to marry me a squaw,

I'll have a big chief for a daddy-in-law.

Got water in the ocean, there's water in the sea,

Since I'm bone dry, it's been water for me,

Been on the Southern, the Seaboard too,

It takes a Henry Ford for to shake me and you.

Oh, me and my partner, we both went to bed,

The jug of white lightning right under my head,

When I woke up the stopper was pulled,

My jug it was empty, but my partner was full.

I've Got The Mourning Blues

I've Got the Mourning Blues

Been in business and I been in love,

I used to fly high like a turtle dove,

Had the blues many a-time,

Just a woman on a poor man's mind

Chorus:

I got the mourning blues, oh so bad,

Honey, come and kiss me, they're the worst I've ever had.

Ashes to ashes and its dust to dust,

Show me a woman that a man can trust.

Nickel's worth of grease and a dime's worth of lard

I would buy them all but the times is so hard.

There ain't no use of me a-working so hard,

For I got a woman in the white folk's yard,

She brings me meat and she brings me pie,

Me eats some of everything the white folks buy.

She brings me chicken and she brings me cake,

You just ought to see me lick that plate,

A big honey biscuit and a mutton chop,

Will make a nigger's lips go flippy flop.

Lassus a fellow right over there,

He's got blue eyes and he's got black hair.

Talking to his sweetheart, she looks so neat,

She calls him honey, and he calls her sweet.

There stands a feller right over yonder,

He looks just like he wants to ponder.

Look at that hair all around his mouth,

Like he swallered a mule and left the tail a-hanging out

It has been said that All In Down and Out Blues refers to the Wall Street crash of 1929. However, as Uncle Dave recorded All In Down and Out Blues three years earlier, in 1926, this cannot be the case. This seems to be a song that Uncle Dave probably composed himself and it certainly suggests that life 'was not all roses' for some time prior to the 'Great Crash'.

Chorus:

It's hard times, Billy, poor boy,

It's hard times, when you're down and out.

Well this is the truth and it certainly exposes,

Wall Street's proposition was not all roses

I put up my money to win some more,

I lost all I had and it left me so sore.

I thought I would drink to wear it off,

Bootleg so high that it left me worse off.

If they catch you with whiskey in your car,

You're handicapped and there you are.

They'll take you to jail and if you can't make bond

Content yourself there, by you're certainly at home.

I've got no silver and I've got no gold,

I'm almost naked and it's done turned cold

You ask that judge to treat you well

You owe four hundred dollars or he'll send you to Atlanta.

They got the arcade blues, got the arcade blues,

Got the arcade blues so bad

Got the arcade blues, got the arcade blues,

That's a trouble I never had, that's a trouble I never had.

These silk dressed women, these silk dressed women,

This arcade's always had

These silk dressed women, these silk dressed women,

Make a married man feel sad.

If you've got a good woman, if you've got a good woman,

I'd advise you to leave her at home,

These arcade boys, these arcade boys,

Won't let a good woman alone, won't let a good woman alone.

If you've got a good woman, if you've got a good woman,

Don't never bring her to town,

But a red headed woman, yes a red headed woman,

Make a grey rabbit love a hound, make grey rabbit love a hound.

Gonna lay my head, gonna lay my head,

Upon some railroad track,

It'll carry me away, it'll carry me away,

But it will not bring me back, oh, it will not bring me.

Said a rubber tire hearse, yes, a rubber tire hearse,

Like a great big cadillac,

Carry you over to the graveyard boys, that man won't bring you back,

That man won't bring you back, that man won't bring you back.

Oh, that is the way my troubles start

Got the heartaching blues, just as blue as the sky

I love that gal, like a schoolboy loves his pie

Laughs

I never shall forget that day

I never shall forget that day

When my baby went away to sea

Oh, when my baby went away to sea

I do not like the young folks much

I do not like the young folks much

For they haven't got the married-folks (touch?)

For they haven't got the married-folks (touch?)

Got the heartaching blues, just as blue as the sky

I love that gal, like a schoolboy loves his pie

Laughs

Some folks says that a Ford won't run,

Just let me tell you what a Henry done,

She left Louisville about half past one,

Oh, she got into Nashville at the setting of the sun.

Chorus:

On the Dixie, on the Dixie Beeline,

Gonna rise and shine, gonna stay up to time,

Rise and shine g'wine to keep/stay up to time,

When I ride in that Henry of mine.

Henry Ford went to Mussell Shoals,

To bring to the people of the South pure gold,

Let him have it says oh, my Lord,

We'll all ride to heaven on a Henry Ford.

That old Buick, said you treated me mean,

Took all my money for to buy gasoline,

She may be warm, but I don't know,

But a Buick won't come where a Henry will go.

Went to the mountains for to get some booze,

The Henry Ford car was the one I choose,

The officers got right on me, I say,

I pulled her wide open and made my getaway.

Everybody knows the Henry Ford car,

Everybody knows they're the best they are

You want to take a ride just get in a Ford,

And six or seven times says, Oh my Lord.![]() 54

54

As we all hastened, right on our way

For home and rest that night

But before that storm was over, you know

So many were killed outright

That mighty storm was sweeping across

Making so many miles per hour

Carrying along, right with it too

A river of drenching power

Then came a mighty, sudden crash

That brought us (such?) pain and death

And in the minds of the living yet

I'm sure they will never forget

There's many a grieved and sad heart we know

In the town of Cherry today

Who's loved-ones, we know, who can never return

To drive all the gloom away

For the dreadful and most terrible sight

Amidst all the pouring down rain

Some who were dead and some dying too

Suffering most death and pain

No tongue can ever live to tell how bad

No pen can ever write

No-one will know, but those living yet

The harrow of that night

There's a little town by the name of Cherry Hill

It all seemed bright and gay

When just like a flash, the Master called

They had no time to pray

For it came right along, in a moment of time

The awful work was done

And many souls were called home that night

That have made their final run.![]() 55

55

Not all of the disasters in 20th century Tennessee, however, were natural. On 5th May, 1925, John Thomas Scopes, a teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, was charged with violating Tennessee's Butler Act, which banned the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools. The case became famous, or infamous, throughout the world as the 'Scopes Monkey Trial'.

Not all of the disasters in 20th century Tennessee, however, were natural. On 5th May, 1925, John Thomas Scopes, a teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, was charged with violating Tennessee's Butler Act, which banned the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools. The case became famous, or infamous, throughout the world as the 'Scopes Monkey Trial'.

The trial ended with Scopes being found guilty and fined $100. However, this decision was overturned on appeal, the Tennessee Supreme Court saying that the judge had set the fine, rather than the jury! Incredibly, the Butler Act remained in force until 1967, when it was repealed. In 1980 I was asked to give a talk at a school in Tennessee. During a coffee break I asked if evolution was now taught in the school. There were some embarrassed looks from the staff, before somebody said that they 'overlooked' that part of the syllabus. Needless to say, Uncle Dave would have approved of this action. This is what he had to say about such events in 1926, the year after the Scopes trial.

(Chorus) God made the world and everything's in it.

He made man perfect and the monkey wasn't in him.

What you say, what you say, Bound to be that way.

(spoken) Lord, yes!

I'm no evolutionist that wants the world to see,

There ain't no man that's anywhere born,

Make a monkey out of me.

Chorus (spoken) Now ain't that right!

Chorus (spoken) You know I'm right!

God made the world and then he made man,

Woman for his helpmate, beat that if you can.

(spoken) Now you know it's so!

God made the world and everything's in it.

He made man perfect and the monkey wasn't in him.

What you say, what you say, Bound to be that way.

(spoken) Lord, yes!![]() 58

58

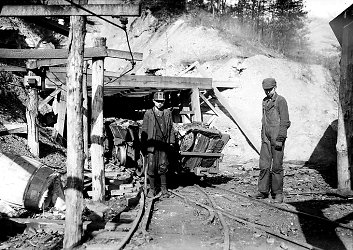

Another important event in Tennessee (and American) history took place during the early 1890s. It seems that the owners of some coal mines at a place called Coal Creek (now re-named Lake City) decided to use convict labour (leased out by the State Government) rather than free miners. Needless to say, the free miners did not like this and violence soon erupted on both sides of the dispute, with dozens of miners and state militia being killed and wounded. Prison stockades were attacked, company building raised to the ground, and hundreds of prisoners released by the miners. In 1892, after a year of struggle, hundreds of free miners were arrested and the dispute came to a rather ragged end. But, public opinion had changed and the Tennessee Governor, John P Buchanan, had to end the system of convict leasing.

Another important event in Tennessee (and American) history took place during the early 1890s. It seems that the owners of some coal mines at a place called Coal Creek (now re-named Lake City) decided to use convict labour (leased out by the State Government) rather than free miners. Needless to say, the free miners did not like this and violence soon erupted on both sides of the dispute, with dozens of miners and state militia being killed and wounded. Prison stockades were attacked, company building raised to the ground, and hundreds of prisoners released by the miners. In 1892, after a year of struggle, hundreds of free miners were arrested and the dispute came to a rather ragged end. But, public opinion had changed and the Tennessee Governor, John P Buchanan, had to end the system of convict leasing.

Several songs and tunes came out of the Coal Creek dispute, or 'War', as some people still call it, most notably Pete Steel's superb pieces Pay Day at Coal Creek and Coal Creek March. Uncle Dave's Buddy Won't You Roll Down the Line was equally popular.![]() 59

59

Chorus:

Oh, buddy, won't you roll down the line?

Buddy, won't you roll down the line?

Yonder come my darling, coming down the line.

Buddy, won't you roll down the line?

Buddy, won't you roll down the line?

Yonder come my darling, coming down the line.

Every Monday morning they've got 'em out on time,

Marched them down to Lone Rock, said, to look into that mine,

March you down to Lone Rock, just to look into that hole,

Very last word the captain say, you'd better get your coal.

The beans they are half done, the bread is not so well,

The meat it is burnt up, and the coffee's black as heck,

But when you get your task done, you're glad to come to call,

For anything you get to eat, it tastes good done or raw.

The bank boss is a hard man, a man you all know well,

And if you don't get your task done, he's going to give you hallelujah,

Carry you to the stockade, as on the floor you'll fall,

Very next time they call on you, you'll bet you'll have your coal.

Chorus:

But now we're up against it and no use to raise a row,

For of all the times I've ever seen we're sure up against it now,

The only thing that we can do, is to do the best we can,

Follow me good people, I'm bound for the promised land.

Now I could be a banker without the least excuse,

But look at the Treasurer of Tennessee and tell me what's the use,

We lately bonded Tennessee for just five million bucks,

The bonds were issued and the money tied up and now we're in the plump?

Some lay it all on parties, some lay it on others you see,

But now that you can plainly see what happened to Tennessee,

For the engineer pulled the throttle, conductor rang the bell,

The brakeman hollered, 'all aboard,' and the banks all went to Hell.![]() 60

60

In 1928 Alfred 'Al' Emanuel Smith, Governor of New York, was selected to be the Democratic US Presidential candidate in that years Presidential Election.

In 1928 Alfred 'Al' Emanuel Smith, Governor of New York, was selected to be the Democratic US Presidential candidate in that years Presidential Election.

Surprisingly, Uncle Dave backed Smith, who was a Yankee, a Democrat and a Catholic. Not exactly the sort of man to endear himself to the American South. But Smith did have one thing in his favour, namely his belief that Prohibition was not working and should be scrapped and so Uncle Dave, who liked his Jack Daniels, came on side with his song Governor Al Smith, which is sung to the tune of The Crawdad Song (Roud 4853).

Al Smith nominated for president, darling

Al Smith nominated for president, darling

Al Smith nominated for president,

My vote to him I'm gonna present, darling.

Al Smith is a mighty fine man, darling,

Al Smith is a mighty fine man, darling,

Al Smith is a mighty fine man,

He want's to be president of our land, darling,

(Spoken) Hot dog, In Chicago, just from Tennessee

and here's what the people say.

Al Smith is a-getting on a boom, darling

Al Smith is a-getting on a boom, darling

Al Smith is a-getting on a boom,

He don't favor no open saloon, darling.

Smith wants everything to be just right, darling,

Smith wants everything to be just right, darling,

Smith wants everything to be just right,

The law's gonna get you if you get tight, darling.

I'm a-going to buy my little camphor gum, darling,

I'm a-going to buy my little camphor gum, darling,

I'm a-going to buy my little camphor gum,

For then I think I can buy a little rum, darling.

Moonshine's been here long enough, darling,

Moonshine's been here long enough, darling,

Moonshine's been here long enough,

Let's all vote right and get rid of this stuff, darling.

Many good men been poisoned to death, darling,

Many good men been poisoned to death, darling,

Many good men been a-poisoned to death,

And with a real drink was never blessed, darling.

Said, a four dollar bills and a bottle of beer, darling

Four dollar bills and a bottle of beer, darling

Four dollar bills and a bottle of beer,

Wish to the Lord my honey was here, darling.![]() 62

62

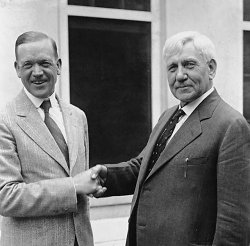

Both Al Smith and Herbert Hoover appear in a further Uncle Dave song, Farm Relief, recorded in 1929.

Both Al Smith and Herbert Hoover appear in a further Uncle Dave song, Farm Relief, recorded in 1929.![]() 64 During the 1920s several attempts were made to pass a bill - the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Act proposed by two senators, Charles L McNary and Gilbert N Haugen - which would have created a federal agency aimed at supporting and protecting domestic farm prices. During World War I the price of agricultural produce in America had risen, but prices fell in the 1920s, as Europe recovered and was capable of self-sufficiency. The Farm-Relief Act was intended to allow the American Government to buy surpluses and give the money back to the farmers. Eventually, in 1928, Congress passed the bill, but it was subsequently vetoed by President Hoover, much to the farmer's dissaproval. Uncle Dave again:

64 During the 1920s several attempts were made to pass a bill - the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Act proposed by two senators, Charles L McNary and Gilbert N Haugen - which would have created a federal agency aimed at supporting and protecting domestic farm prices. During World War I the price of agricultural produce in America had risen, but prices fell in the 1920s, as Europe recovered and was capable of self-sufficiency. The Farm-Relief Act was intended to allow the American Government to buy surpluses and give the money back to the farmers. Eventually, in 1928, Congress passed the bill, but it was subsequently vetoed by President Hoover, much to the farmer's dissaproval. Uncle Dave again:

Farmer just lately moved to town,

Trying every way to cut expenses down,

He lost his job and he didn't do well,

And everybody believes he's gone back farm,

Gone back to the farm, gone back to the farm.

Hoover was elected president,

Al Smith went right down in defeat,

Majority voted for the high, high chief,

But show me a farmer who's got relief,

Who got relief, who got relief.

What a farmer has to buy is too high here,

What he has to sell is too low to make a hit,

Bust up your corporations and your trusts,

For if you don't then farmer's going to bust

Yes the farmer's gonna bust, yes the farmer's gonna bust.

Went in a store for to buy the other day,

Here's just what the merchant had to say,

Nothing doing on Fall terms,

Without their money the wheels won't turn,

Said the wheels won't turn, said the wheels won't turn.

Used to go to church for to hear them shout,

Telling the good Lord what it's all about,

Now the congregation is all so far,

Riding around in a new Ford car,

That a new Ford car, that a new Ford car.

Washington is the law making place,

The poor old farmer hasn't enough to say grace,

If there ain't something done to help his grace,

The poor old farmer's gonna lose his place,

Gonna lose his place, gonna lose his place.

Whole lot of people bought automobiles,

Didn't know how they's a-going to feel,

Rode around so grand and stout,

The note come due, couldn't pay it out.

All they got's gone, all they got's gone.

Whole lot of people had a good little farm,

Doing well and didn't know no harm,

Sold the farm and bought a larger one too,

The notes come to, they had to ski-doo.

All they got's gone, all they got's gone.

Went to the bank for to borrow some money,

Tell you right now I didn't find it funny,

The banker said he have none to loan,

'Get your old hat and pull out home.'

All we've got's gone, all we've got's gone.

Country dudes got the lightning cars,

Tailor made suits and smoking cigars,

Going to the barbershop, pampered and a-rubbing,

Tell you right now, they're (down?) and a-grubby,

All they got's gone, all they got's gone.

Whole lot of farmers want the riding plow,

They had to borrow a tractor to find out how,

When they broke a pin, took a whole lot more,

They better kept walking and a-plowing their mule,

All they got's gone, all they got's gone.

Don't like to see ladies who wear satin dresses,

Their husband bankrupted and in braces and (?)

They better be home washing up kids,

Patching their dresses or their husbands old britches,

All they got's gone, all they got's gone.

Said the bone dry people, says they won't do,

For on the sly, they'll have a whiskey too,

Goodbye brandy, says a-farewell gin,

Thank the Lord, my wife calls me friend,

But all I got's gone, all I got's gone.![]() 65

65

(The clarity of this recording is none too good and I am not 100% certain about one or two words in the above transcription.)

Now you are single, and never heard of jaw,

Don't think of marrying, just think of a mother-in-law

Rolly toodum, toodum, toodum rolly day, rolly too.

Oh, lots of people are married and tied up for life,

But while you are single, you're happier than a wife,

Rolly toodum, toodum, toodum rolly day, rolly too.

And now if you marry, I'll tell you what you'll do,

In pale and working in poverty, you'll wish you're back home too

Rolly toodum, toodum, toodum rolly day, rolly too.

Oh hush your wily talking and stop your silly tongue,

Don't talk of marrying, you know you are too young.

Rolly toodum, toodum, toodum rolly day, rolly too.

And now my daughter listen, I'll give you good advice,

And if you marry a dude, you'll be sorry all your life.

Rolly toodum, toodum, toodum rolly day, rolly too

And now my daughter's married, and what shall I do,

I believe before the sun sets that I'll marry too.

Rolly toodum, toodum, toodum rolly day, rolly too.![]() 66

66

In a number if his songs, Uncle Dave mentions trips to New York, where the northerners treat him like a country bumpkin and try to fleece him of his money. Was this an echo of the feelings between northerners and southerners that had survived from the days of the War? Today, of course, we still laugh at a bumbling John Cleese saying, 'Don't mention the war', when a family of Germans come to stay at his hotel, Fawlty Towers. So, possibly, Uncle Dave was indicating a tension that still existed between the two sides. On the other hand, in some songs Uncle Dave outwits the Yankees, and this reminds me of a number of British songs, such as Walter Pardon's song Bright Golden Store, where a country lad outwits a town girl who tries to steal his money.![]() 68 Perhaps, then, we are looking at an even older tradition here. More problematical is Uncle Dave's vast number of songs that either came to him from black singers or else from white composers who, in the late 1800s and the early 1900s, produced so many 'black' or 'minstrel' songs. This was also a time when the Ku Klux Klan was active in the South. The original Klan was formed in the 1860s, and lasted into the 1870s, as a reaction to events following the southern defeat. But it also re-emerged in the 1920s, when Uncle Dave was making his first recordings. However, there seems to be no mention of the Klan, or of its activities, in any of Uncle Dave's songs. We know that Uncle Dave recorded about 200 songs. This must mean that his records sold well, because, had they not done so, the record companies would soon have dropped him. And many of the songs that he recorded belonged to the genre of 'Minstrel' pieces. We can only conclude that these songs were popular with listeners, some of whom probably yearned for a return to an idealized ante-bellum south, or else to an audience who saw the humour that was clearly intended in some of these songs. Today, of course, such 'humour' is no longer seen to be funny. Thankfully, many of the words, then in common usage, that Uncle Dave used to describe African Americans are also now obsolete.

68 Perhaps, then, we are looking at an even older tradition here. More problematical is Uncle Dave's vast number of songs that either came to him from black singers or else from white composers who, in the late 1800s and the early 1900s, produced so many 'black' or 'minstrel' songs. This was also a time when the Ku Klux Klan was active in the South. The original Klan was formed in the 1860s, and lasted into the 1870s, as a reaction to events following the southern defeat. But it also re-emerged in the 1920s, when Uncle Dave was making his first recordings. However, there seems to be no mention of the Klan, or of its activities, in any of Uncle Dave's songs. We know that Uncle Dave recorded about 200 songs. This must mean that his records sold well, because, had they not done so, the record companies would soon have dropped him. And many of the songs that he recorded belonged to the genre of 'Minstrel' pieces. We can only conclude that these songs were popular with listeners, some of whom probably yearned for a return to an idealized ante-bellum south, or else to an audience who saw the humour that was clearly intended in some of these songs. Today, of course, such 'humour' is no longer seen to be funny. Thankfully, many of the words, then in common usage, that Uncle Dave used to describe African Americans are also now obsolete.

There is also, as I have tried to show above, a duality in some of Uncle Dave's songs, one brought about by Christian morality and the teachings of the church (and don't forget that the Ku Klux Klan was a 'Christian' organization) and the actual lives that people led. Uncle Dave professed to be a Christian, and I am sure that most, if not all, of the people who bought his records would have also said that they, too, were Christians. But there was surely a dichotomy here, one where the church's teachings were not put into practice. I am sure that, to many whites, the term 'love thy neighbour' was not seen as applying to black people. In 1929 a contemporary of Uncle Dave, Blind Alfred Reed, recorded a song There'll Be No Distinction There which was intended to show that we were all equal in the eyes of God. One verse and chorus runs thus:

There'll be no distinction there,

There'll be no distinction there,

For the Lord is just and the Lord is right,

And we'll all be white in that heavenly light,

There'll be no distinction there,![]() 69

69

I could also repeat what I said above about Uncle Dave's attitude to alcohol, both as a Christian and as a drinker. (And don't miss Alfred Reed's brief reference to 'booze' in the song above.) But really this would just confirm how complex the situation is when we consider Uncle Dave and his repertoire, or, indeed, any of Uncle Dave's musical contemporaries and their repertoires. Actually, there is one thing that I do want to say and that is, in order to fully appreciate Uncle Dave, one cannot just read the lyrics; one has to actually listen to Uncle Dave. Only by doing so can we really come to understand him and his songs. There was something special about him, something that the printed word cannot convey, and this quality has been preserved in an almost unique manner. Few, if any, other performers of his generation have lasted so well.

Let me end, then, with a look at a final song Sourwood Mountain Medley, one which in just three minutes manages to incorporate much of what has been said before. It begins with a spoken introduction. It has a couplet that comes from the British song Polly Put the Kettle On, a couple of couplets from the Anglo-American tradition, as well as some topical verses about the Banks. And, for good measure, there is also a Minstrel Show chorus. Take it away Uncle Dave…

Mike Yates - 29.9.10

[1. Uncle Dave]

[2. Uncle Dave's Repertoire]

[Early Influences:]

[Popular & Parlour Songs and Ballads]

[Blues]

[Topical Songs]

[Religious Songs]

[3. Conclusions]

[Acknowledgements:]

[Notes:]

Notes:

Article MT257

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |