Article MT265

Note: place cursor on red asterisks for footnotes.

Place cursor on graphics for citation and further information.

Sound clips are shown by the name of the tune being in bold italic red text. Click the name and your installed MP3 player will start.

Fred 'Pip' Whiting

(1905 - 1988)

"Old-time hornpipes, polkas and jigs"

(MTCD350)

Tracklist:

| Sub-section: "50 years ago by ear"

|

| 1

| Pigeon on the Gate

| 1:01

|

| 2

| Soldier's Joy

| 1:49

|

| 3

| Soldier's Joy

| 1:19

|

| 4

| College Hornpipe

| 1:36

|

| 5

| Earl Soham Slog

| 1:16

|

| 6

| Cock of the North

| 1:14

|

| 7

| Fisher's Hornpipe

| 1:44

|

| 8

| Keel Row

| 1:06

|

| 9

| Off to California

| 1:35

|

| 10

| Garryowen

| 0:58

|

| 11

| Harkie's Polkas

| 1:44

|

| 12

| Not for Joe

| 1:26

|

| 13

| St Patrick's Day

| 1:04

|

| 14

| Harvest Home / Galway Hornpipe

| 2:57

|

| 15

| Old Time Polka

| 2:22

|

| 16

| The Old Kerry Fiddler

| 0:53

|

| 17

| Mountain Belle

| 1:58

|

| 18

| Flowers of Edinburgh

| 1:33

|

| Sub-section: " … the advantage of playing by music"

|

| 19

| Thistle Hornpipe

| 2:41

|

| 20

| West End Hornpipe

| 1:23

|

| 21

| Jack Tar Hornpipe

| 1:37

|

| 22

| Staten Island, or Burns' Hornpipe

| 2:49

|

| Sub-section: "An old Gypsy Hornpipe"

|

| 23

| Billy Harris's Hornpipe

| 1:08

|

| 24

| Whiskey You're the Devil

| 1:37

|

| 25

| Will the Waggoner

| 1:25

|

| 26

| Forty Years Ago

| 1:22

|

| 27

| Bristol Sailorman

| 1:12

|

| 28

| Cutty Sark Hornpipe

| 2:35

|

| Sub-section: "exactly as it's written"

|

| 29

| The Kildare Fancy

| 1:16

|

| 30

| Glasgow Hornpipe

| 1:35

|

| 31

| Ballincollig in the Morning

| 1:37

|

| 32

| Stack of Barley

| 1:26

|

| 33

| Over the Waves

| 2:14

|

| 34

| Hebridean Polka

| 3:15

|

| 35

| Killarney

| 1:43

|

| Sub-section: "a smashing hornpipe for step-dancing"

|

| 36

| Pigeon on the Gate

| 2:37

|

| 37

| College Hornpipe

| 1:24

|

| 38

| Earl Soham Slog

| 2:29

|

| 39

| Manchester Hornpipe

| 1:10

|

| 40

| Pigeon on the Gate / Jack's the Lad

| 1:00

|

| 41

| Fairies' Hornpipe

| 2:02

|

| 42

| Medley

| 3:02

|

|

| Total:

| 72:10

|

|

|

|

Foreword

When Fred Whiting described himself to Keith Summers as a "fiddling freak" he was referring to the fact that despite being left-handed he played a fiddle strung for a right-handed player. But he was a freak - in the proper sense of a curiosity - in many more ways. Born and growing up in a part of the country where traditional music still throve (as it did for another half century or more) - in fact it would probably be fair to say you couldn't get away from it - he tried his hand successively at the mouth-organ, the whistle and the fiddle, "saw the advantage of playing by music" and taught himself as much, made a name for himself as a fiddler and singer in a wide circuit of pubs in his native part of Suffolk, delved into published collections, and went to Australia for work (where he had a number of Irish musicians among his workmates), before returning to Suffolk, and finding himself once again in demand among local step-dancers. He gave up fiddling after injuring one of his eyes, but started playing again after coming into contact with other local musicians, such as Font Whatling from Worlingworth and Dolly Curtis from Dennington, at their tune-ups at Brunsdon Crown and elsewhere, and, of course, renewing his friendship with fellow-fiddler Harkie Nesling of Bedfield. He was not alone in these traits: the fiddler Walter Bulwer at Shipdham in Norfolk had a large collection of printed music, and when he was young Harkie Nesling went to London to play at the Hackney Empire, which must have been as much a cultural shock for him as going to Australia was for Fred. But it is their combination which distinguishes Fred Whiting from other musicians and made him what he was.

When Fred Whiting described himself to Keith Summers as a "fiddling freak" he was referring to the fact that despite being left-handed he played a fiddle strung for a right-handed player. But he was a freak - in the proper sense of a curiosity - in many more ways. Born and growing up in a part of the country where traditional music still throve (as it did for another half century or more) - in fact it would probably be fair to say you couldn't get away from it - he tried his hand successively at the mouth-organ, the whistle and the fiddle, "saw the advantage of playing by music" and taught himself as much, made a name for himself as a fiddler and singer in a wide circuit of pubs in his native part of Suffolk, delved into published collections, and went to Australia for work (where he had a number of Irish musicians among his workmates), before returning to Suffolk, and finding himself once again in demand among local step-dancers. He gave up fiddling after injuring one of his eyes, but started playing again after coming into contact with other local musicians, such as Font Whatling from Worlingworth and Dolly Curtis from Dennington, at their tune-ups at Brunsdon Crown and elsewhere, and, of course, renewing his friendship with fellow-fiddler Harkie Nesling of Bedfield. He was not alone in these traits: the fiddler Walter Bulwer at Shipdham in Norfolk had a large collection of printed music, and when he was young Harkie Nesling went to London to play at the Hackney Empire, which must have been as much a cultural shock for him as going to Australia was for Fred. But it is their combination which distinguishes Fred Whiting from other musicians and made him what he was.

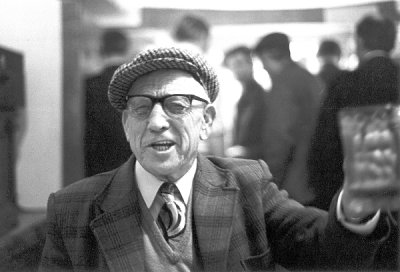

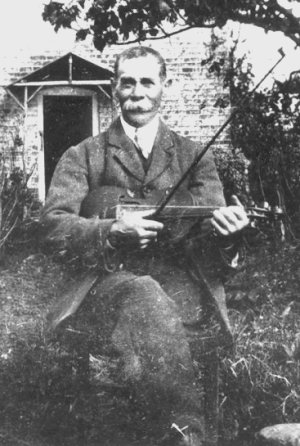

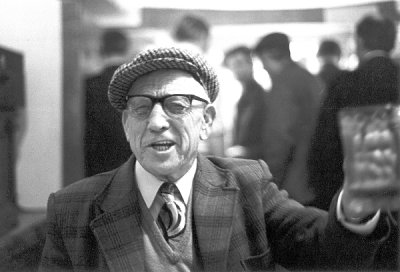

Fred Whiting first came to Keith Summers' attention in 1974, when Keith was visiting the older fiddler, 'Harkie' (Harcourt) Nesling (1890-1978). Keith had seen Harkie on a popular Anglia TV programme called Bygones, singing to his own accompaniment on the fiddle, and inevitably tracked him down to Bedfield - a stone's throw from Fred's home in Kenton - where he spent the afternoon listening to the 'lovable chatterbox' talk, sing and play in the company of "a younger man in his mid-seventies, who said not a word for the next two hours". Keith asked Harkie if he knew any hornpipes. "Well boy", said Harkie, "my old fingers won't get round them these days, but this young man will play a few". The "young man" borrowed one of the four fiddles which hung over Harkie's mantelpiece and played the first of a hundred or so tunes which Keith was to record from him.

Harkie's story has been told elsewhere: the younger man was Frederick Walter Whiting - "but everyone calls me Pip around here." Born into a family with a deep involvement in every aspect of traditional music in the area, Fred learnt his first songs from his father, and when young played the fiddle for his Uncle Jim and his dancing doll, while his cousins Bill and Charlie Whiting were a melodeon-player and prize-winning step-dancer respectively.

Harkie's story has been told elsewhere: the younger man was Frederick Walter Whiting - "but everyone calls me Pip around here." Born into a family with a deep involvement in every aspect of traditional music in the area, Fred learnt his first songs from his father, and when young played the fiddle for his Uncle Jim and his dancing doll, while his cousins Bill and Charlie Whiting were a melodeon-player and prize-winning step-dancer respectively.

Fred's legacy

The interviews which Fred gave to collectors, salted with the asides he made during the recording of his tunes, provide what is probably the most complete personal account by an insider of traditional music-making in this country in the first half of the 20th century. And for this Fred himself provided a soundtrack consisting of the old tunes he brought out when he returned to playing in the 1970s, many of them learnt from Harkie Nesling (who, I should point out, actually called him 'Freddie'), tunes he associated with individual old step-dancers or public houses or originating with previous generations of players, and tunes he learnt from 78s and printed collections.

This CD is devoted to Fred Whiting rather than to East Anglian Traditional Music, though of course what I have described is inevitably Fred's perspective on traditional music-making in East Anglia during his lifetime. Inasmuch as it relates to Fred himself it also contains some of the idiosyncratic tunes with idiosyncratic names which he recorded, and some of the tunes he learnt from printed sources like O'Neill and Allan's Irish Fiddler, which he played socially in later life in a domestic setting with Harkie - and assimilated to the extent that they throw light on his perspective on the older music, some of which Keith saw fit to include on the seminal Topic LP Earl Soham Slog, its name taken from one of Fred's tunes - or rather the step-dancing which was its raison d'etre.

In his own words ...

Fred was born in 1905 at Kenton in Suffolk, a mile or so north-east of Debenham, and getting on for five miles to the west of Framlingham, the son of John Whiting and (Gertrude) Annie, née Taylor.

As I have already indicated, Fred would never need a biographer, for he regaled anyone who was interested with detailed accounts of his life and times. It thus seems appropriate to let him tell his story in his own words:

"My father, John Whiting, wasn't a musician but he knew a hell of a lot of old songs. He was a shepherd and when they were driving sheep round the country they'd often pull up at a pub for the night and have a sing-song and a dance. My mother died when I was only about quarter past five" (Annie Whiting died in 1910 at the age of 27, when Fred was just 5) "so Dad had to look after us and I can remember him singing to me when he put us to bed. He'd sing 'The Ship that Never Returned' or 'The Dark Eyed Sailor' and I'd join in and when I stopped singing he knew that I was asleep".

"My father, John Whiting, wasn't a musician but he knew a hell of a lot of old songs. He was a shepherd and when they were driving sheep round the country they'd often pull up at a pub for the night and have a sing-song and a dance. My mother died when I was only about quarter past five" (Annie Whiting died in 1910 at the age of 27, when Fred was just 5) "so Dad had to look after us and I can remember him singing to me when he put us to bed. He'd sing 'The Ship that Never Returned' or 'The Dark Eyed Sailor' and I'd join in and when I stopped singing he knew that I was asleep".

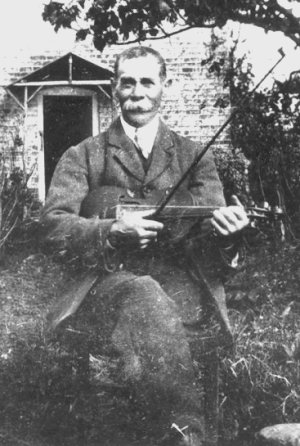

Times were hard, and Fred recalled that when he was a boy itinerant musicians were a regular sight in the area "... surprising the number of people you'd see either playing a fiddle or an accordion or maybe singing ..." though of the instruments which were popular in his own circles Fred was to tell Carole Pegg "In my young days it was either a concertina or a fiddle - the accordions, they came in later". According to Fred it was Tom Salter, who died in the 1st World War, who introduced the 'accordion' (the usual term among traditional musicians in East Anglia for a melodeon) to Kenton Crown. Among the fiddlers he recalled from those days - in addition to his friend Harkie Nesling - was Walter Gyford, a friend of Harkie's from the same village (the two of them - Harkie and Walter Gyford - played in a band with a third Bedfield man, the legendary accordion player Walter Read, who had been blinded in the 1st World War: one of their regular venues was the Bedfield Post Office on Thursdays - pension day!) Another he remembered was 'Fiddler' Billy Harris (1841 - 1931) - a gypsy who hailed originally from Orsett, and later Doddinghurst, both in Essex, whom Fred's wife Winnie remembered wearing an old red neckerchief, with several days growth of whiskers on his chin, and sitting cross-legged on the steps of his brass-covered caravan, where he would 'rattle out' tunes on the fiddle, pausing only to stir with one hand the cauldron of hedgehogs at his feet. Billy Harris would also play for step-dancer Jimmy Knights at Charsfield Horseshoes (Sam Gyford, Walter Gyford's nephew and himself a fiddler, told Keith Summers that the Harrises - "good step dancers" - were the leading lights there).

Fred's first instrument was the mouth organ, which he started playing when he was about twelve. But the reeds "kept going wrong", so he took off the casing and re-tuned them as he'd seen a harmonium player do. "I thought I'd never need to buy another one again. But two days later they went wrong again … and I had to ditch it". At a time when Fred was earning seven shillings a week (35 pence in new money - but the conversion is obviously meaningless), of which he only kept 1/- (one shilling) for himself, he was getting through two mouth organs a week at 3/6d, or half his earnings. Before long he was, in his own words, "that broke I rattled when I walked".

"I often have to grin when it comes to mouth-organs: there'd be five or six of us on the school corner all playing them, and perhaps there weren't more than two of us in the same key, but as long as we played the same tune that was all right. Well I couldn't stand the cost of replacing mouth-organs so I bought a tin whistle, but actually it was a brass whistle, but I could only get about seven notes on that because I didn't know then that by breath control you can get about two and a half octaves on one, and it wasn't until later that I realised how it was done. Anyway, a chap hears me playing in an old rainwater barrel and it rattles in there lovely, and he says: "Will you sell that whistle?" I said: "Yes, I'll sell it". I think I made 3d (three old pence) profit on it, and thought I'd played blazes!"

When he was 16 Fred saved up until he could afford a violin and a bow: "I bought this cheap old German Factory-made fiddle up in Ipswich for 30/- (£1.50) and what I paid for the bow I forget. It was only just a bow. I didn't know a good bow then. I learned to play a few tunes on this violin and then a chap told me I got it strung the wrong way because I was playing it left-handed. So I changed the strings over. Well, I'd already learned to play a few tunes left-handed with the strings on the conventional way. When I changed them over I had to start learning all over again, and on top of that I didn't know I'd have to have the bass bar and sound-post shifted. Well, I sat thinking, if I learn to play like this no-one will be able to play my violin and I won't be able to play theirs, so I put the strings back again and I just carried on playing. Later on I got quite handy at playing by ear, and some people down the road called Chappell (Tom and his wife, at Kenton), they asked me to go down to their place. So away I goes and as far as playing quick music and getting around the corners, I could beat them out and out, but when they started to play by music, well I was stumped. I had to sit and listen to them, so I could see the advantage of learning to play by music, and they put me on to a violin tutor called Honeyman's (William Honeyman's Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor). From there on I went ahead like a house on fire and in those days I only had to play through a bit of music two or three times and I'd never want to see it again".

"I got the fingering positions and did a few little exercises, but I didn't know if I was doing it right or wrong until I came to a tune called 'The Bluebells of Scotland'. Well, I didn't know it as that but as 'Oh where, oh where, has my highland laddie gone', but as I played it through I recognised it and by crikey was I pleased 'cos I knew I was doing it right. Well, a lot of my tunes come from that book and from other people round here - Harkie taught me a lot from other people round here - Harkie taught me a lot of his polkas. My pet hornpipe is 'The Flowers of Edinburgh' - I first heard that when I was about 12 on an old gramophone record by John McClusky, Scotland's champion melodeon player".

The first pub Fred played in was Earl Soham Victoria, and Fred's trademark tune for step-dancing became known as the Earl Soham Slog: "There was an old fiddler down here called West Abbott and I used to go down to his house. I was anxious to learn all I could. Eventually he asked me to go down to the East Soham Victoria and I got a great reception down there and in those days they had a whip-round for you when you'd finished playing. Well if you got two bob or half-a-crown that was a heck of a lot of money in those days. After that Saturday night would find me in pub somewhere. This was after the 1st World War. I used to play in Rishangles Swan, Monk Soham Oak, Henley Cross Keys, Burstall Half Moon - I don't know where I haven't played in my time". According to Fred, at Westleton Crown "about 40 years ago" (i.e. in the 1930s) "every other man was a fisherman. I didn't have the patience for fishing, so I'd knock around there with my old fiddle".

Fred seemed to have a colourful tale to tell about all the pubs he'd played in: At the Rishangles Swan he remembered two old men who would spend the evening dancing over a 'blinking broomstick', and the parting words of a local character by the name of 'Swaler' Parrott (or, in another account, 'Swiver' Farrer), still 'as straight as a crow in a rain storm' after eighteen pints: "Come again, fiddler."

He told Keith Summers: "We were taking some sheep down to Ipswich one Monday night and we stopped at Henley Cross Keys - my old granddad had told me they had a fiddle in there, so when we got our beer I asked the landlord if I could borrow it. Well, he didn't have one. 'You're going back a few years boy' he said, but he got one from his daughter nearby and I played and the place soon filled up. Crikey, we had a ram-sammy that night - I ended up sleeping in a stook of wheat. Next time I was there I didn't have to ask - it came over the bar with our first pint".

"Earl Soham used to be a lively place for music at one time. I've played in the Victoria - 'Earl Soham Beerhouse' it was called because it could only sell beer; it wasn't fully licensed you see. There were so many people in there dancing that I had to play outside at the window. Fred Bloomfield kept it (the singer Alec Bloomfield's uncle) - he was a decent old fellow - and that chap Alf Peachey would play his accordion there. He was really good, and Stumpy Webber, an old bricky from Earl Soham, would step. We had some good nights there". Alf Peachey was a celebrated 'accordion' player who was widely remembered with great respect by other musicians throughout East Suffolk, but was never recorded (except for a spot of diddling) because of a promise he'd made his wife when he got married. "Peachey played in Ashfield Swan too. They had a wooden floor above the cellar and when they were dancing that floor went up and down so much it was a wonder it never caved in!"

"Earl Soham used to be a lively place for music at one time. I've played in the Victoria - 'Earl Soham Beerhouse' it was called because it could only sell beer; it wasn't fully licensed you see. There were so many people in there dancing that I had to play outside at the window. Fred Bloomfield kept it (the singer Alec Bloomfield's uncle) - he was a decent old fellow - and that chap Alf Peachey would play his accordion there. He was really good, and Stumpy Webber, an old bricky from Earl Soham, would step. We had some good nights there". Alf Peachey was a celebrated 'accordion' player who was widely remembered with great respect by other musicians throughout East Suffolk, but was never recorded (except for a spot of diddling) because of a promise he'd made his wife when he got married. "Peachey played in Ashfield Swan too. They had a wooden floor above the cellar and when they were dancing that floor went up and down so much it was a wonder it never caved in!"

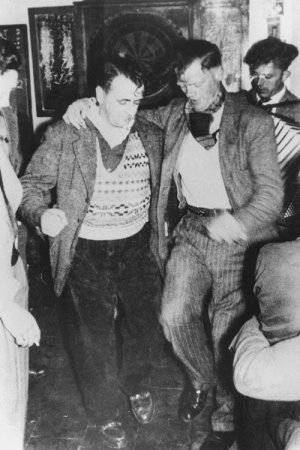

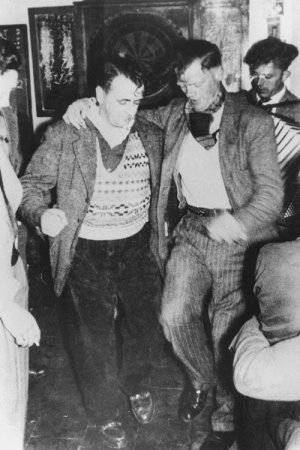

Fred said of the step-dancing at the Earl Soham Victoria: "You might say they had a competition - there'd be one get up behind the other and one get up behind the other, a-trying to outdo each other". Another form of dance which Fred remembered was known as the Cobbler's Dance. Performed only by men, it involved squatting back on the heels and kicking alternate legs out before, like popular conceptions of Cossack dancing, sometimes rotating. Despite its simplicity it required a good sense of balance and not many people were able to perform it. Fred recalled seeing it being performed by 'Tonk' Barham of Earl Soham, and being impressed by his agility. (Elsewhere this dance was performed by two men facing each other and holding hands, when it would be known as the 'Monkey Hornpipe').

"Another good place was Debenham. Bob Keble was the regular player on a Saturday night in the Woolpack and he always went round with a bloke called Jimmy Andrews who played a dancing doll I made for him - and he could do that job".

"Old Billy Harris ... his grandson could step-dance, Alger Harris. I played for him in Charsfield Horseshoes just before I left for Down Under and, by crikey, he could hop. Now some will tell you that Stumpy Webber was the best dancer round here and I can understand that, but the king of them all for my money was an old man called 'Waddley' Cracknell from Kenton" (an assessment which was borne out by Dolly Curtis). "On a stone floor he was pretty to watch and pretty to listen to.  He'd wear these old hobnail boots with heel irons and steel toe pipes and by hell he could clap it in". According to Fred 'Waddley' Cracknell "used to reckon you couldn't stepdance for toffee" (a favourite phrase of Fred's) "if you couldn't stepdance on two bricks".

He'd wear these old hobnail boots with heel irons and steel toe pipes and by hell he could clap it in". According to Fred 'Waddley' Cracknell "used to reckon you couldn't stepdance for toffee" (a favourite phrase of Fred's) "if you couldn't stepdance on two bricks".

In Suffolk step-dancing was free-style heel-and-toe. As Fred said: "You're on your toes and your heel all the time. Different fellas had different ways of doing it - they nearly all had their different ways of ending".

"I used to do a bit at one time. I'd play mouthorgan or fiddle and dance at the same time, but I wouldn't attempt it now. The best I've seen lately are Wattie Wright and Font Whatling when we went down the Swan the other week, and Charlie Whiting from Southolt. Now Charlie and Bill Whiting (he used to play melodeon in Cretingham Bell) and me - our granddads were three brothers.

Australia

In the mid-1920s Fred and his father went to New South Wales for work, following in the footsteps of Fred's uncle Jim, who had fled there after being caught poaching from the Duke of Hamilton, who lived at Easton Mansion. According to Fred his Uncle Jimmy, who could 'fight like the devil himself', gave the keeper who caught him a 'terrific hiding' and fled, the penalty for poaching by night being more severe than that for poaching in daylight, and for fear of being charged with assault and battery into the bargain. As Fred explained: "This would have meant four or five moons in the Government Boarding House, so he bought a long railway ticket and sailed for Australia under his mother's maiden name". This he was able to do on the proceeds of poaching, and still had enough to leave £40 for his mother. As Fred - who was no mean poacher himself - pointed out: "With rabbits 6d each, and hares and pheasants 2/6 each, he must have been a busy poacher".

Fred described his time in Australia as follows: "In the '20s things got pretty tough round here; there was no dole or anything. So a lot of the young lads went to Burton" (on Trent) "for the maltings, or joined the militia - and they always came back with a new pair of boots and little else. Well, in 1926 I decided to go to Australia. I was a bricklayer then and worked out there on the railway, building tunnels" (at Lismore in north-east New South Wales). " I was out there eight years" (Fred's measurement of the passage of time is not entirely consistent with the dates he gives). "I took my fiddle out there and in our camp were several Irish navvies - well I reckon two-thirds of Australians are of Irish descent; 3 or 4 of us had violins. And we were in one place where it rained for nine solid bloody months - we only had two fine days and everything got saturated - blankets, clothes, even our matches we had to dip in wax before you could strike them. Well, all these other blokes, their fiddles came unstuck but mine was hung up in an old calico bag and it stuck it out all that while - whoever made that violin knew his job".

"There were some good musicians over there. A guy called Harry Smith played the concertina and Jim Jackson the tin whistle, but the best music I heard, you'll think I'm daft, but it was out in the bush, were three or four old aborigines sitting in a circle blowing through old gum leaves - boy, you've never heard anything like it. I told you I used to play the tin whistle but I could only get about seven notes out of it. Well, I was coming down the road there one night when I heard this Jim Jackson playing Over the Waves and I rumbled what you could do with breath control - you could get far more notes out of it. So I got away on my own somewhere, so I wouldn't be nuisance, and I was playing Annie Laurie - getting on well with it - and a damned green-head ant crawled up my leg and give me such a bite, well, I played a note in Annie Laurie I reckon you could have heard back at Harkie's! Have you ever heard a parrot sing? I used to have one perched on my tent every morning and I taught it to whistle St Patrick's Day in the Morning. It was comical to hear it. If it went wrong it would stop and go through it again until it was right. So for six months I used to be woken up every morning with St Patrick's Day, and then I never saw it again. I reckon an old carpet snake got it".

"I remember one night I had that old fiddle there, it's a copy of an old Stradivari. Anyway, there was some fellas going over the mountain one Saturday night and I knew they were going on the booze and I didn't want to get mixed up in that. So I went down to an Irishman's place and damned if I didn't run straight into it. They asked me to go and get my fiddle, and I know I ended on my back on a fella's bunk playing '100 pipers'. I can still remember what I was playing, but the next morning when I woke up I wished I could have died. Crikey, no more of that for me".

"I came back to Kenton in 1932 and soon got back into playing around the pubs round here - Rishangles Swan, Dennington Bell, Charsfield Horseshoes, Earl Soham Beerhouse - they were all good in their day, it just depended who kept it". In 1936 Fred married Winnie Branton, who was born in 1913, the daughter of John Branton and Gertrude née Bloomfield.

Dancing dolls

Fred was also celebrated for his dancing dolls, which he both made and danced. He recalled how in his grandfather's day the dancing dolls would come out with the concertinas and fiddles. He made his first at the age of about 14. His Uncle Jim - who he later followed to Australia - had one and Fred would play the fiddle while Uncle Jim danced a doll. Fred tried two dolls together - he found he got better results with two than with one - and then three, which was too many. He stressed the importance of a 'proper board', which had to be thinned down by trial and error until it was right. The dolls had to be light or they wouldn't dance properly on the board. He would dress them up because he thought they looked better, but avoided trousers, which would restrict the movement of the legs, in favour of a woman doll or a Scotsman in a kilt.

... and the bones

Fred was also a lifelong exponent of the bones, which he played 'to help the old rhythm along': He first 'rattled the bones' when he was 13 or 14 with a set he had made out of poplar. He went on to make them out of oak - which was a time-consuming task - preferring the 'snap' he got with a wooden set to the 'click' you got with bone. In later life he admitted to having had - and still having - a 'lot of fun with a set with bones'

Fiddling in East Anglia

To those with an interest in traditional English music and musicians East Anglia will probably mean melodeons (or, more esoterically, dulcimers), but with the possible exception of the North-East the region can also boast the greatest number of recorded traditional fiddlers in England. As well as Fred Whiting, the names of Walter Bulwer, Harry Cox, Harkie Nesling, Herbert Smith, and 'Eely' Whent will already be familiar to anyone who is acquainted with traditional music in the area, and some idea of the density of fiddlers in Fred's own community and its immediate vicinity can be gleaned from the number of fiddlers he refers to in passing in his reminiscences.

To those with an interest in traditional English music and musicians East Anglia will probably mean melodeons (or, more esoterically, dulcimers), but with the possible exception of the North-East the region can also boast the greatest number of recorded traditional fiddlers in England. As well as Fred Whiting, the names of Walter Bulwer, Harry Cox, Harkie Nesling, Herbert Smith, and 'Eely' Whent will already be familiar to anyone who is acquainted with traditional music in the area, and some idea of the density of fiddlers in Fred's own community and its immediate vicinity can be gleaned from the number of fiddlers he refers to in passing in his reminiscences.

Although from the outside East Anglian traditional music might seem to represent a single entity, the vernacular styles found in Suffolk and Norfolk respectively are quite distinct, the Claptonesque precision of such melodeon players as Percy Brown and Bob Davies in North Norfolk, contrasting with the Hendrix-like inspiration of Dolly Curtis and Peter Plant in Suffolk. This contrast is also reflected among fiddlers: compare the austerity of Herbert Smith in Norfolk with the looseness of Fred 'Eely' Whent in Suffolk, for example. This difference is more likely to be due to the influence of respected players than to any more abstract factors. And while Fred Whiting plays his earliest Suffolk step-dancing music in the local vernacular style, his playing of Fisher's Hornpipe, for example, is closer to that of Walter Bulwer in Norfolk, and even Stephen Baldwin in Gloucestershire, and seems to reflect an older, more universal 'classic' hornpipe style. Fred applied this style to some of the hornpipes which he acquired later on, and it may not be going too far to say that in his case at least vernacular style was inextricably tied up with vernacular versions of tunes. Interestingly enough vernacular versions of tunes were played in East Anglia alongside more formal versions of the same tunes: in North Norfolk, for example, the older fiddler Harry Baxter was recorded for the BBC by Seamus Ennis no less in 1955 (when he - Harry - was about 85 years of age) playing the Manchester Hornpipe (which he is more likely to have called the Yarmouth Hornpipe - if anything - himself) in the classic hornpipe style - his sole musical legacy - for Dick Hewitt to step to.

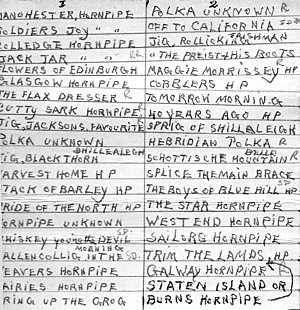

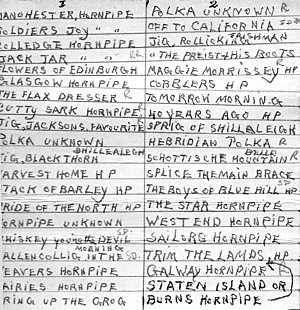

Repertoire

Fred's repertoire represents an amalgam of items acquired over a lifetime's playing. First there are the vernacular versions of hornpipes which he associated with Kenton Crown (the Manchester Hornpipe/Pigeon on the Gate) and his old stamping ground, Earl Soham Victoria (the Earl Soham Slog), with particular step-dancers (the College Hornpipe/Jack's the Lad), or with the old days in general (Harvest Home, Soldier's Joy). Then there are the tunes which everyone had always known: Cock of the North, the Keel Row, St Patrick's Day, and Garryowen. Some of these may be among the tunes he learnt from his friend Harkie Nesling and via Harkie from other local musicians, such as William 'Shirt' Burrows, one of the most highly-regarded fiddlers in the area, who played at Dennington Bell and Brundish Crown and died at the age of 84 in about 1960, and the Gypsy fiddler Billy Harris. When still young he also learnt tunes from 78s (the Flowers of Edinburgh) and from Honeyman's Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor. Later on he learnt tunes from published collections, including (to judge from the versions he played) Allan's Irish Fiddler and O'Neill, possibly his Music of Ireland from 1903 (with its '1850' tunes) rather than the Dance Music of Ireland from 1907 (with its '1001' tunes), judging from the omission of some of O'Neill's versions which Fred plays from the latter and from some of the titles he uses. The transcriptions in O'Neill and Allan's have very little ornamentation or decoration, and while Fred plays some of the tunes he seems to have had from those sources more as less as written, his performances of others (notably Kildare Fancy, Whiskey you're the Devil and the Stack of Barley) betray either a prior acquaintance with those tunes in performance, or an extraordinary empathy with the genre.

Fred's repertoire represents an amalgam of items acquired over a lifetime's playing. First there are the vernacular versions of hornpipes which he associated with Kenton Crown (the Manchester Hornpipe/Pigeon on the Gate) and his old stamping ground, Earl Soham Victoria (the Earl Soham Slog), with particular step-dancers (the College Hornpipe/Jack's the Lad), or with the old days in general (Harvest Home, Soldier's Joy). Then there are the tunes which everyone had always known: Cock of the North, the Keel Row, St Patrick's Day, and Garryowen. Some of these may be among the tunes he learnt from his friend Harkie Nesling and via Harkie from other local musicians, such as William 'Shirt' Burrows, one of the most highly-regarded fiddlers in the area, who played at Dennington Bell and Brundish Crown and died at the age of 84 in about 1960, and the Gypsy fiddler Billy Harris. When still young he also learnt tunes from 78s (the Flowers of Edinburgh) and from Honeyman's Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor. Later on he learnt tunes from published collections, including (to judge from the versions he played) Allan's Irish Fiddler and O'Neill, possibly his Music of Ireland from 1903 (with its '1850' tunes) rather than the Dance Music of Ireland from 1907 (with its '1001' tunes), judging from the omission of some of O'Neill's versions which Fred plays from the latter and from some of the titles he uses. The transcriptions in O'Neill and Allan's have very little ornamentation or decoration, and while Fred plays some of the tunes he seems to have had from those sources more as less as written, his performances of others (notably Kildare Fancy, Whiskey you're the Devil and the Stack of Barley) betray either a prior acquaintance with those tunes in performance, or an extraordinary empathy with the genre.

There is also a group of tunes: such as Will the Waggoner, Forty Years Ago and the Bristol Sailorman which seem to be unique to Fred, and whose melodies have something intangible in common with the melodies of songs which are also unique to him. These may represent his own attempts to recall tunes with associations for him which he celebrated in the equally unique names he used for them. They may, of course, yet be found in a published collection, though this seems unlikely.

... and style

Obviously East Anglian fiddlers all had their own different musical personalities - and sometimes more than one. Fred Whiting approached his old Suffolk tunes and the tunes he acquired later on in quite distinct ways, and both in more ways than one. In part this may reflect the fact that he as much a domestic and social player as a pub musician

Most of Fred's repertoire consisted of hornpipes and similar tunes, reflecting the importance of step-dancing in his community - and to him, of course. In a letter to Katie Howson (reproduced in her collection of East Anglian tunes 'Before the night was out'), he suggested that the most popular hornpipes in Suffolk were the College Hornpipe, the Manchester Hornpipe (this is the name which Fred always gave to this tune, whether in its vernacular or its formal version: in Suffolk it was generally known as the Pigeon on the Gate, which I shall reserve for the vernacular version to avoid confusion), and Soldier's Joy. By and large he was right, but he omitted from his list a hornpipe which seems to have been one of the most popular amongst step dancers and musicians throughout East Anglia, and indeed throughout the country. This was perhaps understandable, inasmuch as he doesn't seem to have played it himself and it was seldom if ever known among traditional musicians by its 'real', or indeed any other name. That tune is the Bristol Hornpipe: in East Anglia this was recorded from Harry Cox (in three versions according to the instrument he was playing), Percy Brown, Oscar Woods, George Craske, Bob Davies, Cecil Pearl (Dick Iris's Hornpipe) and Billy Cooper (who alone of those named played it in something approaching its original form - under the name of the Yarmouth Hornpipe!). George Watson of Swanton Abbott in Norfolk called his version Beckels Hornpipe, perhaps a misspelling of Becket's, rather than a reference to Beccles.

Most of Fred's repertoire consisted of hornpipes and similar tunes, reflecting the importance of step-dancing in his community - and to him, of course. In a letter to Katie Howson (reproduced in her collection of East Anglian tunes 'Before the night was out'), he suggested that the most popular hornpipes in Suffolk were the College Hornpipe, the Manchester Hornpipe (this is the name which Fred always gave to this tune, whether in its vernacular or its formal version: in Suffolk it was generally known as the Pigeon on the Gate, which I shall reserve for the vernacular version to avoid confusion), and Soldier's Joy. By and large he was right, but he omitted from his list a hornpipe which seems to have been one of the most popular amongst step dancers and musicians throughout East Anglia, and indeed throughout the country. This was perhaps understandable, inasmuch as he doesn't seem to have played it himself and it was seldom if ever known among traditional musicians by its 'real', or indeed any other name. That tune is the Bristol Hornpipe: in East Anglia this was recorded from Harry Cox (in three versions according to the instrument he was playing), Percy Brown, Oscar Woods, George Craske, Bob Davies, Cecil Pearl (Dick Iris's Hornpipe) and Billy Cooper (who alone of those named played it in something approaching its original form - under the name of the Yarmouth Hornpipe!). George Watson of Swanton Abbott in Norfolk called his version Beckels Hornpipe, perhaps a misspelling of Becket's, rather than a reference to Beccles.

Fred played the oldest items in his repertoire - that is to say the items he acquired early on in his playing career - in what might be called the East Anglian vernacular style: his Pigeon on the Gate and Earl Soham Slog are fast, and relentlessly rhythmic, with minimal finesse, but larded with the (upper) mordents ('the original note, the note above, the original note') and triplets ('three consecutive notes in the time of two') which are the stock in trade of the East Anglian fiddler, especially in hornpipes, but do not seem to feature to the same extent (if at all) in the playing of fiddlers elsewhere in southern England. In the vernacular style the classic hornpipe with its successive groups of four (semi-) quavers has been pared back to its rhythmic minimum, and it is possible that this development might have had its origins in an attempt to cut through the noise in a public house. The vernacular style is perhaps more common among East Anglian melodeon (and mouth-organ) players, but among fiddlers it finds its glorious apogee in the playing of Harry Cox.

Fred also played these tunes and his other stepping tunes differently according to whether he was playing for step dancing or not, and intriguingly he seems to have played more legato (smoothly) and less rhythmically when he was playing for a dancer. No real comparison can be made on this point however, inasmuch as no other fiddlers seem to have been recorded playing the same tune in isolation and for step-dancing.

However, Fred did play other 'standards' in the classic hornpipe style: his Fisher's Hornpipe may be compared with Walter Bulwer's version (which he called the Egg Hornpipe), for example. This is a style which Fred translated to hornpipes in general circulation like Off to California, and to some of the tunes he took from Honeyman's Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor, the Thistle Hornpipe and Burn's Hornpipe (Staten Island) being particularly good examples. He also treats some of the tunes he apparently got from O'Neill and Allan's Irish Fiddler in the same way, and his interpretations of the Kildare Fancy, Whiskey you're the Devil and the Stack of Barley - each of them highly individual in a completely different way - exemplify how effectively he assimilated tunes he learnt - or re-learnt - from print to his existing style.

But Fred seems to have eschewed the slurring on to the beat and across bar boundaries which characterises the classic English hornpipe style as exhibited in these and other examples not only in tunes which might elsewhere be considered reels, and were perhaps originally 'Scotch measures' (such as Soldier's Joy and Flowers of Edinburgh), but also in some of the tunes he seems to have found in O'Neill, such as Ballincollig in the Morning and the Fairy Hornpipe, which he plays 'straight'. And while he may have learnt his 'rough and ready' stepping tunes from a rough and ready (though not necessarily unsophisticated) fiddler, like Harry Cox or 'Spanker' Austin, and his more sophisticated local hornpipes from a more sophisticated fiddler like Harry Lee or Walter Bulwer, it's not impossible, of course, that the dichotomy was already apparent in earlier generations of fiddlers with whom he came into contact.

One particularly conspicuous feature of Fred's playing (ironically, given his respect for the printed page) is the way in which he consistently lengthens or shortens specific bars in many of his tunes, whether learnt orally or from print (playing 'crooked' as it's known across the Atlantic).  This trait appears in his very earliest tunes - Pigeon on the Gate/Manchester Hornpipe - and standards like Off to California. His only real shortcoming is in his intonation, in that his pitch on the top string - the E string - is sometimes a little sharp, possibly because of the way he tuned it.

This trait appears in his very earliest tunes - Pigeon on the Gate/Manchester Hornpipe - and standards like Off to California. His only real shortcoming is in his intonation, in that his pitch on the top string - the E string - is sometimes a little sharp, possibly because of the way he tuned it.

The recordings

Fred was recorded playing scores of tunes for the late Keith Summers, John Howson and Carole Pegg, and he also made taped recordings of himself for Keith and others, identifying one of them as Old-time hornpipes, polkas, jigs etc. As much use has been made of the latter as possible, to avoid duplicating Keith's own recordings which can be listened to on the National Sound Archive website. The recordings are of varying quality, but even the poorest are good enough, we feel, to give an accurate impression of Fred in his own environment.

Acknowledgements

These notes are based largely on an extended article by Keith Summers (Sing, Say or Pay, in the Late 1977/Spring 1978 issue of the paper version of Musical Traditions, which he edited), and on Carole Pegg's doctoral dissertation Music and Society in East Suffolk for the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge (June 1985), both of which include material which is based on Fred's own accounts of his life. I am grateful to Carole for her permission to quote from her work, and to Keith, wherever he is, for not minding that I have done so.

Afterword

In 1977/78 Keith Summers wrote: Fred virtually gave up playing about 20 years ago when he had a bad time with his eyes but fortunately he was cured at Ipswich Hospital, and when he retired about five years ago he became interested in playing again, especially on his visits to Harkie. After our first meeting I sent him a couple of records of country music and this really did the trick. He practises quite a lot and is going through all his old tune books and polishing up. Most of his tunes come from sheet music, with a very high proportion of Scots and Irish hornpipes, but he still plays many of the old local tunes he learnt as a boy.

Recently he has even started playing in the pubs again, such as Worlingworth Swan, Brundish Crown, and even Blaxhall Ship, often with Cecil Fisk, who plays a dancing doll. But as he says "Memory's a funny thing - if you ask me what I did last week I wouldn't know, but 50 years ago - it all comes back and I think a lot about those times".

Fred Whiting was one of the last great English traditional musicians. Being a fiddler, he was never feted like Scan Tester or Bob Cann, or William Kimber before them. In fact he was sometimes regarded with suspicion because traditional fiddlers are meant to sound rough and shouldn't be able to read music. The fact that he was self taught, and had been learning tunes from the printed page since his youth was neither here nor there, and the fact that he approached and performed them with nothing but the sensibilities of a traditional musician was always overlooked. The problem was that he was a good musician and as such did not readily fit preconceived notions of the traditional fiddler: not in England at any rate. Where else would a traditional musician of his calibre be so neglected on principle?

In 1999 Keith Summers wrote, in a postscript to Sing, Say or Pay, of the 'men with a knowledge of their tradition far beyond their immediate community (long-headed men, as Neil [Lanham] calls them)'. Fred Whiting was such a man, and his exploitation of his exposure to traditional musicians and music outside his immediate milieu also made him that rare thing, a modern traditional musician, of the kind which was common in Ireland and Irish communities elsewhere, but almost completely unheard of in England outside the northeast. His neglect is also in part due to that uniqueness: in England traditional music is regarded very much as their own common property by its modern enthusiasts, who don't know what to do with exceptionally musical traditional players like Fred Whiting.

Tune Notes:

In the following notes, the source of the recording is given after the title of the tune(s) as follows:

NSACD1-3: 3 CDs of recordings by Keith Summers in the National Sound Archive;

FW/KS: recordings made for Keith Summers by Fred Whiting, supplied on cassette by Peta Webb and digitised by Philip Heath-Coleman.

"50 years ago by ear"

1- Pigeon on the Gate [NSACD1]

"I suppose it's the best known hornpipe in Suffolk" said Fred of a tune which is generally known there as the Pigeon on the Gate, and in Norfolk as the Yarmouth Hornpipe. "But", as he added, "in any book you look in it's always the Manchester Hornpipe." He recalled "As a young boy I stood outside Kenton Crown, and the first music I ever heard was the Manchester Hornpipe" (this was what Fred usually called this tune, but it was never used by other East Anglian musicians), "and you might safely say it's about the most popular hornpipe around here." In East Anglia this tune was found in as any many forms as there were musicians who played it, but every variant is recognisable as such. Although, like many other traditional musicians, Fred later acquired a more formal version (see Track 28), "this is the way we used to play it about fifty years ago by ear."

2 - Soldier's Joy [FW/KS]

According to Fred the Soldier's Joy ran the Manchester Hornpipe a close second in popularity among local musicians. It was collected from many traditional musicians in East Anglia, and Keith Summers recorded a particularly spirited rendition from another Suffolk fiddler, Arthur 'Spanker' Austin, of Woodbridge, which can be heard on the National Sound Archives website. Fred Whiting recorded many of his tunes on more than one occasion and on more than one fiddle (both his own and Harkie Nesling's). As the second recording of Soldier's Joy (track 3) shows, the results were not always the same.

3 - Soldier's Joy [NSACD1]

4 - College Hornpipe [FW/KS]

Known locally as either the Sailor's Hornpipe or Jack's the Lad (a name which gave rise to the popular designation of step-dancing as 'Jack-the-Ladding'), Fred Whiting described this as the third most popular tune for step-dancing in Suffolk. Unlike melodeon players, fiddlers tended to play all the notes, but recorded versions tend to be closer to the version in Sir Henry Wood's Fantasia on British Sea Songs (which, incidentally, he called Jack's the Lad) than to the version made famous by Popeye. "The man who put the most steps into a hornpipe that I ever heard was old sailor Jack Abbott. He always insisted you played him the College Hornpipe, or Jack's the Lad as they call it, and play it slow. Could he put some steps into that."

5 - Earl Soham Slog [NSACD1]

This tune, which seems to be a version of the ubiquitous 'four-hand reel' tune, is more frequently found in Norfolk, where it is known, amongst other things, as the Sheringham Breakdown, the Yarmouth Breakdown and the Norfolk Step Dance. One of Fred's favourite stepping tunes, his name for it derives from its association with step-dancing at the Victoria public house in Earl Soham, once known locally as the Earl Soham Beerhouse: "about the fastest step-dancer I ever knew was a chap called 'Stumpy' Webber, and he always used to dance to what we call the Earl Soham Slog."

6 - Cock of the North [NSACD2]

Most traditional musicians seem to have acquired this tune after it attained universal popularity (perhaps because of its use as a march, and/or for the Gay Gordons) but before the 'standard' version was set in stone, and, like Fred, were happy to play versions which differed from the modern norm. In Suffolk (and elsewhere) it was often used for the broomstick dance (although the stick would not always be attached to a broom-head), and was sometimes known as Over the Stick for that reason.

7 - Fisher's Hornpipe [NSACD2]

Fiddler Walter Bulwer of Shipdham in Norfolk, whose performance is similar to Fred's, called this tune the Egg Hornpipe, the name by which it was also known to the Northamptonshire poet and fiddler John Clare over a hundred years previously. This tune seems once to have been as popular everywhere as the Manchester Hornpipe, the Soldier's Joy or the College Hornpipe.

8 - Keel Row [NSACD2]

Notwithstanding its Northumbrian associations, this tune has long been known throughout the British Isles: Fred's 'scotch snaps' may be evidence of Caledonian influence in his version - Jimmy Shand recorded it as part of a 'highland schottische' set in 1942 - but that device was never exclusively Scottish.

9 - Off to California [NSACD1]

Fred described this as "one of my old pet hornpipes", and it was among the tunes he would bring out in company for step-dancing, always adding an extra half-bar for good measure to accommodate the classic 'om pom pom' ending of other hornpipes. Otherwise he follows O'Neill, with whom the name (although not the tune - it is found in a mid-19th century manuscript collection from Lancashire and in Kerr's Merry Melodies simply as a Clog Dance) seems to have originated. His ease and familiarity with the tune is underscored by the way he launched into a robust rendition of the tune inadvertently when meaning to play Pigeon on the Gate (Track 1), but quite how 'old' an item in his repertoire it was is not readily apparent.

10 - Garryowen [NSACD1]

A tune which may owe its deathless popularity to its use as a march, it was recorded from a number of traditional musicians in East Anglia. One of a small group of Irish jigs which seem to have crowded out most other tunes in 6/8 from the traditional repertoire in the 20th century, possibly because of their former intimate association with quadrilles.

11 & 12 - Harkie's Polkas [FW/KS & NSACD1]

11 & 12 - Harkie's Polkas [FW/KS & NSACD1]

"Harkie taught me a lot from other people round here … Harkie taught me a lot of his polkas." Although East Anglia is often thought of as a stronghold of the polka, most of the polkas which were widely played were actually once-popular songs: here Fred plays two such tunes associated with Harkie Nesling, which derive ultimately from nineteenth-century songs; James Pierpoint's One Horse Open Sleigh, first published in 1857 and now better-known as Jingle Bells, and Arthur Lloyd's Not for Joe dating from 1867. Both were in the repertoires of many Suffolk musicians, and are associated with the celebrated melodeon players Ernie Seaman and Alf Peachey. Although Fred apparently had them from his older friend and fellow-fiddler Harkie Nesling, his (Fred's) rendition of the first is quite different in bars 7 and 8 of the first strain, where he follows the version associated with Alf Peachey as played by Dolly Curtis, who might have influenced him. The second part as played traditionally in Suffolk seems to owe more to the original second part of James Pierpoint's tune, which is rather different from the second part as sung today. Interestingly enough, the original tune is also found under the name of the Snow Drift Gallop in the manuscript tune book of George Watson of Swanton Abbott in Norfolk dating from 1883.

13 - St Patrick's Day [NSACD1]

Although widely known as a military march, especially among Irish regiments, this tune had a vigorous life of its own among traditional musicians not only in East Anglia but throughout the country. It is found in a variety of forms, from the idiosyncratic version shared by Stephen Baldwin in Gloucestershire (which he called Flanagan's Ball) and Billy Bennington in Norfolk (which he called Sir Roger de Coverley), to the standard country dance version played (with multiple variations) by, among others, Percy Brown in Norfolk, via versions which are quite close to the regimental march, as played by Billy Cooper in Norfolk and here by Fred Whiting.

14 - Harvest Home / Galway Hornpipe [FW/KS]

"One that you don't hear around here much now, the Harvest Home" paired with "a great favourite of mine, the Galloway Hornpipe." Both these tunes, the former long established in England (and ultimately a variation on the Cliff Hornpipe) and the latter a more recent import from Ireland, courtesy, perhaps, of Allan's Irish Fiddler, were popular with musicians in East Anglia, the former being recorded from Dolly Curtis and the latter from both Percy Brown and Sonny Barber. Fred Whiting was not alone in confusing Galway in Ireland with the region of Galloway in south-western Scotland (though he wrote the name as 'Galway').

15 - Old Time Polka [FW1]

"An old-time polka I never did know the name of" is as much as Fred had to say about this tune.

16 - The Old Kerry Fiddler [NSACD1]

An Irish-sounding jig which doesn't seem to occur elsewhere but shares its melodic impulse with tunes like the Blackthorn Stick. Fred may have learnt the tune from Irish musicians in Australia: it's hard to imagine any other context where he might have heard the source described as a 'Kerry fiddler'. Or perhaps the name is his own.

17 - Mountain Belle [FW/KS]

A schottische which was popular both within and beyond East Anglia.

18 - Flowers of Edinburgh [FW/KS]

"One of my favourites has always been the Flowers of Edinburgh." Fred's is a fairly standard, if slightly 'crooked' version, of which he told Keith Summers: "My pet hornpipe is The Flowers of Edinburgh - I first heard that when I was about twelve, on an old gramophone record by John McClusky, Scotland's champion melodeon player." Unfortunately there is no record of any such person or recording!

"… the advantage of playing by music …"

While still young, Fred 'saw', to put it in his own words, "the advantage of playing by music, so I went away and bought a copy of Honeyman's Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor and got the fingering positions and did a few little exercises … A lot of my tunes come from that book ..."

19 - Thistle Hornpipe [FW/KS]

In print, this and the next tune seem to be peculiar to Honeyman, although the B music of the Thistle Hornpipe reappears as the B music to O'Neills 2nd setting of Off to California. The tune, or rather the first part, was also recorded (as the Sailor's Hornpipe) from George Davis in New South Wales (his second strain resembling that of the Manchester Hornpipe).

20 - West End Hornpipe [FW/KS]

"This one's the West End Hornpipe, the first hornpipe I learnt to play in my life." Another tune from Honeyman. For some reason Fred also referred to this tune as 'Harkie Nesling's step dance'.

21 - Jack Tar Hornpipe [FW/KS]

English musicians tend to avoid minor keys, perhaps because for them they have always evoked a kind of stage spookiness, but some admitted the odd minor tune, like Fred and the Jack Tar Hornpipe. The tune is old, and apparently spawned the Cuckoo's Nest. But it was also recorded on 78 by the Scots-born (Nottingham-based) concertina player Alexander Prince as part of a medley featuring a selection of unnamed hornpipes (all in Kerr's Merry Melodies), the rest of which - apart from the last - might be an East Angliaan step-dancer's litany: Blakeney Hornpipe, Manchester Hornpipe, Millicen(t)'s Favourite, Jack(y) Tar, Wonder Hornpipe, Kerr (vol. 1) Hornpipe no. 8.

22 - Staten Island, or Burns' Hornpipe [FW/KS]

Fred used both titles given in Honeyman (thus revealing his source – at least for the name!). As Staten Island this tune was also recorded in Norfolk from Percy Brown. Its universal popularity in modern times, which seems to have originated with Dave Swarbrick, has resulted in its being described variously as an Irish or American tune, but its real antecedents are Scottish. Jimmy Shand's 1942 recording on 78 may be the origin of its popularity among traditional musicians in this country.

"An old Gypsy Hornpipe"

23 - Billy Harris's Hornpipe [FW/KS]

"I've never seen a gypsy fiddler who doesn't know this hornpipe, and I've never seen one yet who knows the name of it." Carole Pegg refers to a tune called Billy Harris' Hornpipe after its source, as an example of a tune named in that way. Fred didn't actually record a tune under that name, but Harkie Nesling sang it for Keith Summers to indicate the tune which Billy Harris was playing in the Crown in Framlingham on the occasion when Harkie acquired Billy Harris's fiddle some time before the 2nd World War. Billy Harris, a gypsy who originally hailed from Essex, was long remembered as a musician locally, in particular in association with step-dancing. Of his grandson. Alger Harris, Fred observed: "I played for him in Charsfield Horseshoes … and by crikey he could hop!"

Most people would probably regard this tune as a schottische, but that tune type seems to have coalesced in the popular mind with the slow hornpipe, perhaps because of its use for step-dancing. The second strain of the tune repeats the first at a higher pitch: we don't know if this was a feature of Harkie Nesling's or Billy Harris's own rendition of the tune, or even if in this form it ever had a distinct second strain.

24 - Whiskey You're the Devil [FW/KS]

Long before O'Neill published it under this name, this tune - which bears an obvious similarity to Off to California - was to be found simply as a Clog Dance in England and in Scotland, and as Miss Johnson's Hornpipe in America. Fred used O'Neill's title, referring to the tune as an (Irish) Gypsy Hornpipe, a soubriquet which is also in O'Neill, and may derive from Howe's 1,000 Jigs and Reels (c.1867), where it is the only name given to the tune. In New South Wales Harry Cotter, of Schottische fame, also recorded a spirited version of this tune.

25 - Will the Waggoner [FW/KS]

"An old gypsy hornpipe" - this tune and its name, and the three tunes (tracks) which follow and their names, do not seem to occur anywhere else. They share elements of their melodic content with similar 'one-off' tunes and songs in Fred's repertoire and may be local - or even Fred's - takes on other tunes. It's possible that Fred bestowed his own names on the tunes: do the name of this tune and Fred's description of it point towards Billy Harris?

26 - Forty Years Ago [FW/KS]

O'Neill has an (unrelated) tune called Thirty Years Ago, and it's possible that Fred made up a similar name for a tune which he recalled from that time.

27 - Bristol Sailorman [NSACD1]

Possibly a reference to Fred's source.

28 - Cutty Sark Hornpipe [FW/KS]

Despite Fred's assertions about its origins on board the famous clipper, there seem to be no other recorded sightings of this tune.

"exactly as it's written"

Honeyman's Tutor was by no means the only published collection which Fred delved into for his own amusement. He obviously had access to one of O'Neill's collections (probably his only possible source for the Kildare Fancy - by that name - and the Glasgow Hornpipe), and perhaps the Dance Music of Ireland where Whiskey You're the Devil is sub-titled Gypsy Hornpipe.

29 - The Kildare Fancy [NSACD1]

Fred seems to have been drawn in particular (perhaps inevitably) to hornpipes in O'Neill with English or Scottish analogues (and perhaps an English or Scottish feel), and although he seems to have played them for his own (and Harkie Nesling's) amusement, he often made them his own. O'Neill's Kildare Fancy (possibly his own ascription in honour of his source), which is also found, untitled, in the mss of George Watson in Norfolk (see above), was recorded as the Dundee Hornpipe (the name which Kerr gives the tune) by Jimmy Shand in 1942, paired with Millicent's Favourite - something of a party piece among East Anglian musicians in Fred's day - and Fred's spirited rendition may betray familiarity, direct or indirect, with a recorded version.

30 - Glasgow Hornpipe [FW/KS]

Other than in O'Neill, this tune is only found in an early 19th century Scottish manuscript.

31 - Ballincollig in the Morning [FW/KS]

Another name apparently bestowed by O'Neill in honour of his native county, Fred observed of this tune: "One of my favourites is Ballincollig in the morning: I always think it's a smashing hornpipe for step dancing."

32 - Stack of Barley [FW/KS]

Fred's tune resembles the version of the same name in Allan's Irish Fiddler, and differs from the version in O'Neill, who calls it the Little Stack of Barley, which suggests the former may have been Fred's source.

33 - Over the Waves [NSACD2]

Originally composed (as Sobre las ondas) by the Mexican composer Juventino Rosas (1868 - 1894), and first published in 1884, this tune's extreme popularity may ultimately have been due to its association with the fairground organ. It's still very popular in the USA, and Art Galbraith plays it on MTCD509.

34 - Hebridean Polka [FW/KS]

One of the newest items in Fred's repertoire, this splendid tune - which is usually described as a hornpipe, but could also be classed as a schottische - was composed in 1973 by Alex M MacIver, President of the Glasgow Lewis and Harris Association.

35 - Killarney [NSACD1]

A duet with Harkie Nesling featuring a once popular tune composed by the Irishman Michael William Balfe (1808-1870). With few exceptions (see Over the Waves), traditional English musicians seem to have reserved their first gear for sentimental Irish song tunes of this kind.

"a smashing hornpipe for step-dancing"

It's easy to forget that this music served a practical purpose - in fact a dual practical purpose: to accompanying step-dancing and to provide a soundtrack for the consumption of often prodigious quantities of beer (both frequently 'to destruction'). Here, then, are a few recordings of Fred doing both, in this case at Brundish Crown in the 1970s.

36 - Pigeon on the Gate (with Cecil Fisk and dancing doll) [NSACD3]

Fred always lengthened the third bar of the first strain when he played his version of this Suffolk take on the Manchester Hornpipe (quite the opposite to what he did to the published version: see note to Track 28).

37 - College Hornpipe (with Wattie Wright step dancing) [NSACD3]

Wattie Wright was an old friend of Font Whatling, and the pair were known for their step-dancing á deux.

38 - Earl Soham Slog (with Cecil Fisk and dancing doll) [NSACD3]

See note to Track 5.

39 - Manchester Hornpipe (with Wattie Wright step dancing) [NSACD3]

"Here it is played exactly as it's written" said Fred, despite the fact that he always played it 'crooked', conflating the last two bars of each strain. Not that that seems to have thrown Wattie Wright.

40 - Pigeon on the Gate / Jack's the Lad (Fred Whiting on bones with Font Whatling on melodeon) [NSACD3]

Himself a celebrated step dancer and, like Fred, one of the last of the real old musicians, Font Whatling (1918 - 1998) was a protégé of the equally celebrated blind melodeon-player Walter Read of Bedfield (1894 - 1971).

41 - Fairies' Hornpipe (with Cecil Fisk and dancing doll) [NSACD3]

Another tune which Fred can only have found in O'Neill.

42 - Medley [NSACD3]

(Irish Washerwoman / Weaver's Hornpipe / Soldier's Joy / Pigeon on the Gate (with Cecil Fisk and dancing doll) / Flowers of Edinburgh / Blackthorn Stick / Jackson's Favourite)

Fred plays a medley of popular 'standards' and his own favourites. The Weaver's Hornpipe doesn't seem to occur anywhere else, and Jackson's Favourite (which seems to be distantly related to both the Maid at the Well and The Muckin' o' Geordie's Byre) is only found in Allan's Irish Fiddler, which seems to confirm that Fred used that collection as well as O'Neill and Honeyman. Fred - inevitably - says "… it's a favourite of mine too", but its inclusion in this medley suggests he may have meant it.

Credits:

All of the foregoing was researched and written by Philip Heath-Coleman. My sincere thanks to Phil, and to the late Keith Summers for the photos.

The Keith Summers Collection is at the British Library. Original digitisation from the originals was done by the British Library.

Booklet: editing, DTP, printing

CD: editing, formatting,

production, by Rod Stradling

A Musical Traditions Records production © 2011

Article MT265

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 3.3.12

When Fred Whiting described himself to Keith Summers as a "fiddling freak" he was referring to the fact that despite being left-handed he played a fiddle strung for a right-handed player. But he was a freak - in the proper sense of a curiosity - in many more ways. Born and growing up in a part of the country where traditional music still throve (as it did for another half century or more) - in fact it would probably be fair to say you couldn't get away from it - he tried his hand successively at the mouth-organ, the whistle and the fiddle, "saw the advantage of playing by music" and taught himself as much, made a name for himself as a fiddler and singer in a wide circuit of pubs in his native part of Suffolk, delved into published collections, and went to Australia for work (where he had a number of Irish musicians among his workmates), before returning to Suffolk, and finding himself once again in demand among local step-dancers. He gave up fiddling after injuring one of his eyes, but started playing again after coming into contact with other local musicians, such as Font Whatling from Worlingworth and Dolly Curtis from Dennington, at their tune-ups at Brunsdon Crown and elsewhere, and, of course, renewing his friendship with fellow-fiddler Harkie Nesling of Bedfield. He was not alone in these traits: the fiddler Walter Bulwer at Shipdham in Norfolk had a large collection of printed music, and when he was young Harkie Nesling went to London to play at the Hackney Empire, which must have been as much a cultural shock for him as going to Australia was for Fred. But it is their combination which distinguishes Fred Whiting from other musicians and made him what he was.

When Fred Whiting described himself to Keith Summers as a "fiddling freak" he was referring to the fact that despite being left-handed he played a fiddle strung for a right-handed player. But he was a freak - in the proper sense of a curiosity - in many more ways. Born and growing up in a part of the country where traditional music still throve (as it did for another half century or more) - in fact it would probably be fair to say you couldn't get away from it - he tried his hand successively at the mouth-organ, the whistle and the fiddle, "saw the advantage of playing by music" and taught himself as much, made a name for himself as a fiddler and singer in a wide circuit of pubs in his native part of Suffolk, delved into published collections, and went to Australia for work (where he had a number of Irish musicians among his workmates), before returning to Suffolk, and finding himself once again in demand among local step-dancers. He gave up fiddling after injuring one of his eyes, but started playing again after coming into contact with other local musicians, such as Font Whatling from Worlingworth and Dolly Curtis from Dennington, at their tune-ups at Brunsdon Crown and elsewhere, and, of course, renewing his friendship with fellow-fiddler Harkie Nesling of Bedfield. He was not alone in these traits: the fiddler Walter Bulwer at Shipdham in Norfolk had a large collection of printed music, and when he was young Harkie Nesling went to London to play at the Hackney Empire, which must have been as much a cultural shock for him as going to Australia was for Fred. But it is their combination which distinguishes Fred Whiting from other musicians and made him what he was.

Harkie's story has been told elsewhere: the younger man was Frederick Walter Whiting - "but everyone calls me Pip around here." Born into a family with a deep involvement in every aspect of traditional music in the area, Fred learnt his first songs from his father, and when young played the fiddle for his Uncle Jim and his dancing doll, while his cousins Bill and Charlie Whiting were a melodeon-player and prize-winning step-dancer respectively.

Harkie's story has been told elsewhere: the younger man was Frederick Walter Whiting - "but everyone calls me Pip around here." Born into a family with a deep involvement in every aspect of traditional music in the area, Fred learnt his first songs from his father, and when young played the fiddle for his Uncle Jim and his dancing doll, while his cousins Bill and Charlie Whiting were a melodeon-player and prize-winning step-dancer respectively.

"My father, John Whiting, wasn't a musician but he knew a hell of a lot of old songs. He was a shepherd and when they were driving sheep round the country they'd often pull up at a pub for the night and have a sing-song and a dance. My mother died when I was only about quarter past five" (Annie Whiting died in 1910 at the age of 27, when Fred was just 5) "so Dad had to look after us and I can remember him singing to me when he put us to bed. He'd sing 'The Ship that Never Returned' or 'The Dark Eyed Sailor' and I'd join in and when I stopped singing he knew that I was asleep".

"My father, John Whiting, wasn't a musician but he knew a hell of a lot of old songs. He was a shepherd and when they were driving sheep round the country they'd often pull up at a pub for the night and have a sing-song and a dance. My mother died when I was only about quarter past five" (Annie Whiting died in 1910 at the age of 27, when Fred was just 5) "so Dad had to look after us and I can remember him singing to me when he put us to bed. He'd sing 'The Ship that Never Returned' or 'The Dark Eyed Sailor' and I'd join in and when I stopped singing he knew that I was asleep".

"Earl Soham used to be a lively place for music at one time. I've played in the Victoria - 'Earl Soham Beerhouse' it was called because it could only sell beer; it wasn't fully licensed you see. There were so many people in there dancing that I had to play outside at the window. Fred Bloomfield kept it (the singer Alec Bloomfield's uncle) - he was a decent old fellow - and that chap Alf Peachey would play his accordion there. He was really good, and Stumpy Webber, an old bricky from Earl Soham, would step. We had some good nights there". Alf Peachey was a celebrated 'accordion' player who was widely remembered with great respect by other musicians throughout East Suffolk, but was never recorded (except for a spot of diddling) because of a promise he'd made his wife when he got married. "Peachey played in Ashfield Swan too. They had a wooden floor above the cellar and when they were dancing that floor went up and down so much it was a wonder it never caved in!"

"Earl Soham used to be a lively place for music at one time. I've played in the Victoria - 'Earl Soham Beerhouse' it was called because it could only sell beer; it wasn't fully licensed you see. There were so many people in there dancing that I had to play outside at the window. Fred Bloomfield kept it (the singer Alec Bloomfield's uncle) - he was a decent old fellow - and that chap Alf Peachey would play his accordion there. He was really good, and Stumpy Webber, an old bricky from Earl Soham, would step. We had some good nights there". Alf Peachey was a celebrated 'accordion' player who was widely remembered with great respect by other musicians throughout East Suffolk, but was never recorded (except for a spot of diddling) because of a promise he'd made his wife when he got married. "Peachey played in Ashfield Swan too. They had a wooden floor above the cellar and when they were dancing that floor went up and down so much it was a wonder it never caved in!"

He'd wear these old hobnail boots with heel irons and steel toe pipes and by hell he could clap it in". According to Fred 'Waddley' Cracknell "used to reckon you couldn't stepdance for toffee" (a favourite phrase of Fred's) "if you couldn't stepdance on two bricks".

He'd wear these old hobnail boots with heel irons and steel toe pipes and by hell he could clap it in". According to Fred 'Waddley' Cracknell "used to reckon you couldn't stepdance for toffee" (a favourite phrase of Fred's) "if you couldn't stepdance on two bricks".

To those with an interest in traditional English music and musicians East Anglia will probably mean melodeons (or, more esoterically, dulcimers), but with the possible exception of the North-East the region can also boast the greatest number of recorded traditional fiddlers in England. As well as Fred Whiting, the names of Walter Bulwer, Harry Cox, Harkie Nesling, Herbert Smith, and 'Eely' Whent will already be familiar to anyone who is acquainted with traditional music in the area, and some idea of the density of fiddlers in Fred's own community and its immediate vicinity can be gleaned from the number of fiddlers he refers to in passing in his reminiscences.

To those with an interest in traditional English music and musicians East Anglia will probably mean melodeons (or, more esoterically, dulcimers), but with the possible exception of the North-East the region can also boast the greatest number of recorded traditional fiddlers in England. As well as Fred Whiting, the names of Walter Bulwer, Harry Cox, Harkie Nesling, Herbert Smith, and 'Eely' Whent will already be familiar to anyone who is acquainted with traditional music in the area, and some idea of the density of fiddlers in Fred's own community and its immediate vicinity can be gleaned from the number of fiddlers he refers to in passing in his reminiscences.

Fred's repertoire represents an amalgam of items acquired over a lifetime's playing. First there are the vernacular versions of hornpipes which he associated with Kenton Crown (the Manchester Hornpipe/Pigeon on the Gate) and his old stamping ground, Earl Soham Victoria (the Earl Soham Slog), with particular step-dancers (the College Hornpipe/Jack's the Lad), or with the old days in general (Harvest Home, Soldier's Joy). Then there are the tunes which everyone had always known: Cock of the North, the Keel Row, St Patrick's Day, and Garryowen. Some of these may be among the tunes he learnt from his friend Harkie Nesling and via Harkie from other local musicians, such as William 'Shirt' Burrows, one of the most highly-regarded fiddlers in the area, who played at Dennington Bell and Brundish Crown and died at the age of 84 in about 1960, and the Gypsy fiddler Billy Harris. When still young he also learnt tunes from 78s (the Flowers of Edinburgh) and from Honeyman's Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor. Later on he learnt tunes from published collections, including (to judge from the versions he played) Allan's Irish Fiddler and O'Neill, possibly his Music of Ireland from 1903 (with its '1850' tunes) rather than the Dance Music of Ireland from 1907 (with its '1001' tunes), judging from the omission of some of O'Neill's versions which Fred plays from the latter and from some of the titles he uses. The transcriptions in O'Neill and Allan's have very little ornamentation or decoration, and while Fred plays some of the tunes he seems to have had from those sources more as less as written, his performances of others (notably Kildare Fancy, Whiskey you're the Devil and the Stack of Barley) betray either a prior acquaintance with those tunes in performance, or an extraordinary empathy with the genre.