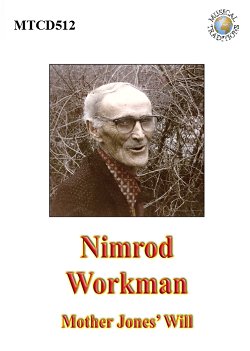

Article MT264

Nimrod Workman

Mother Jones' Will

MTCD512

Musical Traditions Records' fourth NAT CD re-release: Nimrod Workman: Mother Jones' Will (MTCD512), is now available. See our Records page for details. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the record, or who might find the small print hard to read, I have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here.

Tracklist:

1. Lord Baseman

2. My Pretty Little Pink

3. The City Four Square

4. Sweet Rosie

5. Lord Daniel

6. Remember What You Told Me, Love

7. Rock the Cradle and Cry

8. Coal Black Mining Blues (Nimrod Workman/Happy Valley Music, BMI)

9. Mother Jones' Will (Nimrod Workman/Happy Valley Music, BMI)

10. The Drunkard's Lone Child

11. What Is That Blood on Your Shirt Sleeve?

12. Working on This Old Railroad

13. Black Lung Song (Nimrod Workman/Happy Valley Music, BMI)

14. I Want To Go Where Things Are Beautiful

15. Biler and the Boar

16. The Devil and the Farmer

17. Loving Henry

18. Darling Cory

19. The Stone that was Hewed Out of the Mountain

20. Little David, Play on Your Harp (with Molly Workman)

21. Brother Preacher

22. In the Pines

23. Newsy Women

24. Oh, Death

25. The Carolina Lady

26. Little Bessie (with Molly Workman)

Autobiographical remarks:

My people came up into Kentucky to settle when there were no houses in the place at all - just hundreds of acres of ground in the wilderness. Maybe your nearest neighbors would be twenty-five or thirty miles away. Those were hard times back then - and dangerous times too. Back there in Martin County is a place they call Panther Lick. My grandfather was living there when he heard this hollering and screaming and he peeked out of the cracks and saw a big black panther coming out of that lick across a big high log. And just then a big bear had come in at the other end and they met plumb in the middle of the log, each trying to make the other back up. They locked into it and that panther ripped that bear's belly open until his guts fell out, but that old bear kept a-hugging on him until they fell off that log. They both died right there in that lick: the panther hugged up in the bear's clutches. And that's where my people settled in Kentucky.

One night my grandmother was sitting in the cabin all alone and she heard this panther a-hollering out around the house. There was a hole into that log house right near the chimney and this old panther started to run his paw up through there to get at her while she's knitting. Well, my grandmother just grabbed his leg behind his paw, and set her broom up against it and rolled her yarn all around that broom and the panther's claw. The old panther, he worked all the rest of the night to get his leg out and when my grandpa came back the next morning, he killed it.

My grandfather Workman had come from England and fought back in that Old Rebel and Yankee war. He drawed a pension of fifteen dollars from whichever side he was on. He'd gotten one of his eyes put out fighting around a tree with a tomahawk or something like that. I was named after him and he'd always take my part in any kind of argument. When he was real old and any of the kids tried to gang up and were getting too hot for me, I'd run up to him and he'd whop them with his cane. I had a lot of brothers and sisters and we had happy times back then and there was no aggravation like there is now. Of course we had to work hard all the time, but when we did get time to play, we'd really enjoy it. We'd play right out through the woodland, stuff like All Around the Mulberry Bush, Dog Chews the Bone, and all sorts of funny games like that. And we'd cut big grapevines loose and swing way out over the hillsides on them.

I started humming these songs off when I was about twelve years old. Most of my old-time singing I got from my people on both sides. Maybe I'd take some of one song and some of another and put them together - just cut and dry them myself you know, and that way I'd make a pretty good song out of them. And I used to attend those real old-timey churches when I was a boy and I learned a lot of these Christian songs too. I used to play a French harp but these old-timey Baptists didn't believe in music in church and, if you mentioned it to them, they'd say that 'way back music was hung up on the willows and done away with. The only thing they believed in was music and prayer.

When I got a little older and was working in the mines, me and lots of the single fellers would buy a half gallon of moonshine with our scrip and go sit on the railroad tracks or just somewhere in the mouth of the holler. And they'd give me a nick of liquor to sing some. I had a good clear voice back then and I could pitch her out there. I'd sing these old love songs and they'd get me to sing Christian songs too. Just sitting out there singing until maybe one or two o'clock of the night.

Those were the days of that Hatfield and McCoy war. I remember old Devil Ance Hatfield himself - boy, if something roused him up, the bugger man got right into him and he didn't care for nothing. If a bunch of them met out somewhere, they'd ask, "What's your name?" - "I'm a McCoy" - "Well I'm a Hatfield. Roll up your sleeves, we're going into it." You had to be careful yourself when you were over in their country. If you'd be leaving out of a night, they might think you were over there to see a girl and they'd rock you. Buddy, the rocks would just hail down like walnuts a-falling!

When these old-timers would fight, they'd fight like mules until the blood would fly. They'd stand up and knock her out and they knew how to knock her too! One night I got my nose broken seventeen ways in a fight with the Evans boys. I was into it with one of them and I ducked him and his arm went plumb through a Number Two zinc washtub hanging on the wall. My daddy got mixed up in it and he knocked two of these boys out, but another of them pitched a big rock right on top of my daddy and we thought he was killed. My Uncle Mack grabbed a wellpole and just about killed us all - he was so mad he didn't know one of us from the other. He'd just holler, "You've killed Harvey" and that old wellpole was a-singing "zup" "zup" "zup". We took my daddy home and that was one rough, tough night. We didn't think he'd ever come to. And so I got so I didn't fool with that fighting stuff.

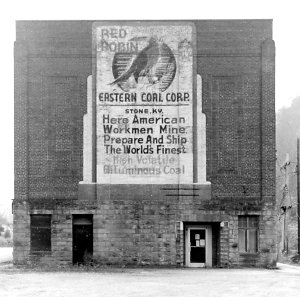

I went into the mines when I was fourteen years old. I was working as a backhand, cleaning up for old Jesse Winchester in a place which was running eight and nine cars of coal.  I was doing all that for fifty cents and a supper of cornbread and sweet milk, so I says to myself, "Why should you be loading eight and nine cars of coal for him, with him getting three dollars out of it and you only getting fifty cents?" Finally I buckled up to the mine foreman and explained the thing to him. He says to me, "But you're too young to work in the mines; I can't give you any checks."

I was doing all that for fifty cents and a supper of cornbread and sweet milk, so I says to myself, "Why should you be loading eight and nine cars of coal for him, with him getting three dollars out of it and you only getting fifty cents?" Finally I buckled up to the mine foreman and explained the thing to him. He says to me, "But you're too young to work in the mines; I can't give you any checks."

I answered right back, "I'm not too young to work as a backhand and if that top'll fall on me working with my own checks, it'll still fall on me working for fifty cents a day." So we got my parents to sign a minor's release and the next day I told old Jesse, "Buddy, I've got checks of my own - this is my place now." Well, he got awful mad over that, because that caused him to lose out.

I worked there at Brockton for several years. I was laying track, driving mules and hauling coal. And we made our own shots back then, too. You'd roll your paper, tuck it in, and pour it full of powder. You'd run this copper needle to the back of the coal where you'd drill in with a breast auger. They used a squib in those days, with a little thing like a fire cracker at the end of it. You'd light that and it'd burn blue like sulphur and run that hole back into your powder and shoot your coal.

That was back in the time of old Woodrow Wilson's War. I had been exempted because I was taking care of my dad and family, but I was ready to go up in the next call. Well, I was working in the cornfield one day with my daddy when I heard all the whistles a-blowing up at the mines, and on all these freight trains running up and down the river. And the people out on their farms over on the Kentucky side started ringing on their plows. "There's peace," they said. "We've run old King Kaiser in the vault." And that was the last I ever heard about him.

It was just about that time that Mother Jones came around. Me and my Uncle George were working at Ajax, up on this side of Lenore, when a feller by the name of York came in the mines and called us out. "We're on strike and taking applications for union members. If you want to take the risk of being a scab ... why, that's up to you." So my uncle and I stacked our tools and came out. I got a five dollar check a month from Mother Jones, and a single man, who wasn't looking after nobody, got three dollars.

Yeah, I was right up into the Mother Jones' time. I used to roll out these big old buggies for her to get up on, to make her speeches. She'd talk to us men just like a sergeant in the army. She'd tell us all to be careful and that if anytime a yellow dog was shooting into a bunch of us, we should try to get his eyeball. "Try your best to get his eyeball," she'd say. Buddy, she was a tough woman. Before she'd went to leading, she went into the mines and drove mules. Her husband was a union man from somewheres, and when he died she hauled coal, so that she could be called a union member. She told a bunch of gun thugs once, "I've sat on a bumper inhaling mule farts and it smelled better than you son of a bitches, a-carrying guns and shooting people." Brother, she didn't care what she'd say. Her hair hung way down, just as grey as it could be, with those big high cheekbones - there wasn't a man any tougher than she. She didn't worry about the thugs and the guns. She used to tell them, "You won't shoot me. I won't turn my back to you and let you shoot me in no back of the head."

There were a lot of people killed back then. They'd bar a union man from going to the store, and a lot of times we wouldn't have anything to eat. The thugs killed one union man, tied his neck to the back of a truck and drug him up and down Tug River. One time when the men were out fighting in the hills, the thugs came into the miners's tents and slapped all the women around and poured kerosene in the milk for the babies. Those poor little babies, just crying out for hunger. That's why I put that in my song about Mother Jones.

I was over in the Blair Mountain Strike when they killed the High Sheriff, John Gore. I sat up in a tower on the top of the gap, looking and a-watching and that day I left my initials in it, cut out with an old barrow knife. Another time they were having it out at Matewan and my cousin and I were on the top of a point in Hatfield Hollow on the Kentucky side. I told him, "Daniel, sit down, because the scabs are down in there and they're liable to spy out and get you." But he climbed up on top of that rock anyway, and pretty soon I heard a high powered rifle crack and he pitched off that rock cliff and rolled down the hill. Someone wrote up a report telling that he was out hunting and fell off the cliff by accident.

They killed the sheriff, Sid Hatfield, for siding with the union. The company brought charges against him and told him to come unarmed to Welch, West Virginia; they didn't want to try him in his hometown of Williamson. Well, they had it all cut and dried: those thugs were planted around that courthouse when Sid came up there unarmed. Sid's wife fell on one of the thugs and jabbed big holes in his arm with the staves of her parasol, just trying to keep him from shooting at Sid. But they got him anyway. Boy, that teared it; we started sending them scabs down the road, Buddy, just as fast as they'd gather. We were cleaning them out. At Merrimac, there wasn't a sound glass in the son of a bitch; the window glasses were all knocked out.

But the coal companies got ahold of the federal government someway and Uncle Sam sent the soldiers down here. They marched up the river and ordered a ceasefire. The miners didn't know that they'd take sides like they did. Finally, Mother Jones said, "We've got to surrender." The companies were paying all these scabs about thirty dollars a day, when the miners used to get a buck and a half. So Mother Jones told the bosses, "We'll be back - the union'll come back. And when she comes back, you'll send for it."

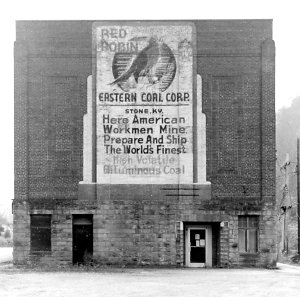

Well, we didn't get her back until 1933. Until then, times were pretty rough. Maybe you'd work about three days of the week in the mines. They paid you $2.80 a day for sixteen to eighteen hours of work with no overtime. And you'd get paid in a brass scrip dollar, if you were lucky enough to get that far ahead. Me and Molly had a couple of children by then and rent was three dollars for two weeks, your coal was a dollar and so was your doctor bill. If you loaded coal, you had to buy your own powder and supplies. Your wife would go to the store to ask for a dollar scrip and the book-keeper would ring up to the top of the hill where the coal dump was, to ask "How many cars has so-and-so dumped?" Maybe the word was, "He ain't got it in here yet. He can't get no scrip until we get the rent and stuff first." And when it rained, the water leaked into the house and you'd have to set pans on the floor to catch it with. The company wouldn't fix the roof and you couldn't buy any paper to do it yourself because you never drawed any money to buy it with - just traded all your scrip right there at the company store.

When you couldn't make enough to eat on account of the mines not working enough, you'd have to walk all the way to Williamson to get some Red Cross flour and old yellow pieces of hog jowl and rice that the rats had been into. That flour read 'Not to be Sold' all over it, but they'd sure work you all day for it, building a park or some amusement to get it. Old Doc Ingram'd walk up and down with a big long pole making you stand in line for the Red Cross stuff.

About then I asked the old man for a raise. "Mr Morrison, you're working us sixteen and eighteen hours a day," I said. "But eight hours constitutes a day's work." He told me, "We don't count no eight hours up here. You'll work until the cars are dumped and fixed up for the night shift, regardless of what time it is." And then he said, "Workman, do you see that road down yonder?"

"Sure. I'm not blind, I guess I can see it." "Well there's a miner walking up and down that road wearing pawpaw galluses and living on a cracker a day, just waiting for your job if you're not satisfied with it." And it was like that all through those Hoover days.

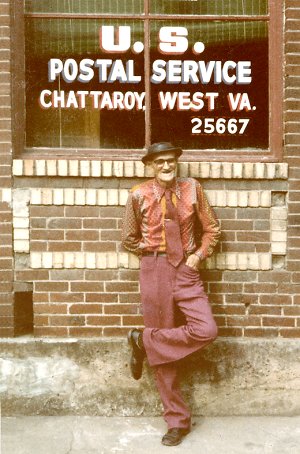

I had stayed by the union through the Mother Jones time, and we had failed to get organized. So when John Lewis came out in 1933, I was the second man in Chattaroy Holler to sign up. I met John Lewis in Charleston, in the ball park and went everywhere, until we got the union organized and on its feet. I helped get the first local started down here in Buffalo Creek. Over in Kentucky, there were several places that didn't come out with us, so we went and picketed and brought them out. We went into the mines where they were cutting, and made them leave their machines slumped up against the face. We stopped their scabbing against the locals, and put the union in good shape so we could handle it. We ruled it the way it was supposed to be, and according to the way we took our obligation. Not like today, where they treat an old or disabled miner like me as only a half-brother in the union.

We were on strike back in through the head of Pigeon Creek when the coal companies tried to get the government to come back in again. Well, Governor M M Neely came in alright, but he didn't go against the union. And we saw that we finally had backing, and that he didn't aim to do anything against us. Then when we got into the big war, the money men didn't want to give us a raise or anything else we asked for, so they contacted the Federal government. Old Roosevelt said, "Boys, we're in a war and need the coal, so go back to work and I'll see that you get the raise. If you don't, I'll set an embargo against the mines and the Federal government'll run her."

When we went back to work, the superintendent said, all friendly-like, "I'm going to give you all a raise, being's how you've decided to come back to work." I said, "Yeah, you're going to give us our raise because President Roosevelt said he'd run it himself if we didn't get that raise!" Well, that superintendent looked like a dog that had killed a sheep; he didn't know what to say.

But then they set up a law which I'll never forget. Old Taft and Hartley said, "Roosevelt, drive these men back in the mines. Make them go back to work." But Roosevelt said, "You can lead a horse to water, boys, but you can't make him drink. I can drive the men back in the mines but I can't set right there beside them and make them load the coal. So leave it to me, boys. I'll get them back." And that's how we got our raise.

After the war, my health went bad. I was crawling around in twenty-two inch coal and it cut my hands up so bad, I had to go to the hospital to have them worked on. After that I went on the roll for the Crystal Block people and worked there for two years, but in 1948 I got hurt pulling a pan. I got a slipped disc in my back - it's there yet - and I couldn't even stoop over to go in the mines. I went to the hospital but the doctor was bought off and said he couldn't find any mine-related injuries. I'd been in the mines for forty-two years but the Board said I had to have five years after 1946 to be eligible for a miner's pension. And there was no Social Security then either. Well, the Board has been ordered to pay it, but they said I should be drawing state compensation for being hurt in the mines. Well, how can you draw state compensation if the company didn't ever sign you up and send it over to the State? I don't think the young coal miners of today know how hard it was to bring this union to them and to get their wages up so high. I think if they did, they'd hold up better for the old people and break that Welfare Board all to pieces. Miller's not done it. He said, "When I get in there, fellers like Nimrod are going to get their Miner's Welfare," but I haven't got my pension yet - forty-two years in the mine and eighty-three years old.

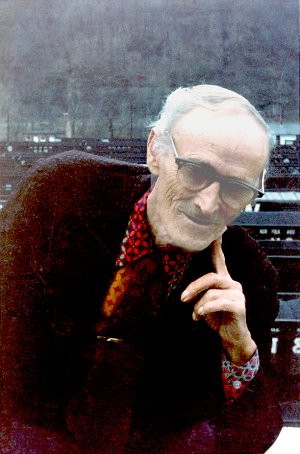

Nimrod Workman

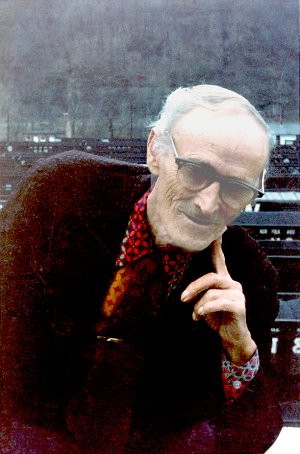

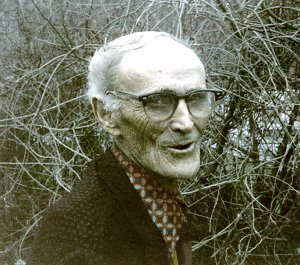

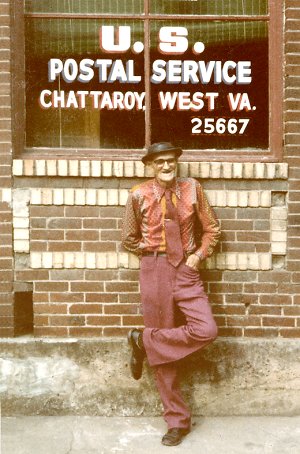

Nimrod Workman first came to the attention of Rounder Records' Ken Irwin and Marian Leighton through Nimrod's involvement in the union movement of the early 'seventies. His daughter, the late Phyllis Boyens, was then married to a young UMW lawyer who had come to help out in the coal camps, and Nimrod was sometimes asked to sing some of his self-composed songs at benefits and rallies. Phyllis had previously sung with Nimrod on his June Appal LP and was a singer in her own right who eventually made an LP of her own for Rounder (she later worked as an actress in the well-known movie Coal Miner's Daughter, in which Nimrod also briefly appears). Nimrod had also supplied several of his own songs to an earlier (1973) Rounder compilation, Come All You Coal Miners. As a result of these contacts, Ken and I traveled to Chattaroy in March 1976, when the music on this CD was recorded over a several day period, including the rather extensive interviews from which the above autobiography has been extracted. I, of course, was delighted with Nimrod's broad knowledge of old songs and featured many of these (bands 1-18) on the LP (Rounder 0076) that was issued in late 1976. Other numbers from this session can be heard on:

Musical Traditions MTCD341-4, Meeting's a Pleasure

Rounder 4026, Harlan County USA: Songs of the Coal Miners' Struggle

Rounder 8141, The Land of Yahoe: Children's Entertainments from the Days before Television

Rounder LP SS-0145, Traditional Music on Rounder

Other issued recordings by Nimrod are June Appal 001, Passing Through the Garden and Drag City 379, I Want to Go Where Things Are Beautiful (from Mike Seeger recordings). Nimrod can also be seen in a number of films, including Appalshop's Nimrod Workman: To Fit My Own Category and several videos by Alan Lomax.

As always, we are grateful for the support provided by Ken Irwin and Bill Nowlin of Rounder, which made much of our recording work possible. Such thanks are particularly called for in the context of the present material, as it was Ken who initiated the project in the first place.

Mark Wilson

The Songs:

1. Lord Baseman (Child 53, Roud 40). It often struck me, in discussing such songs with my informants, that these old ballads probably served the mountain people as useful relics of an older morality, in a manner allied to that which Homer and Virgil provided for more literate audiences. In this vein, I was often told that the antics of Lord Baseman, Mathie Groves and the Carolina Lady would worry my informants greatly as children, leading them to muse upon 'the right thing to do' in such situations. As such, the old ballads conveyed a breeze of exoticism into a society where moral evaluation otherwise ran along conventionally constrained rails (even if moral action itself did not). This song was commonly printed in early American songsters and proved well enough known in Victorian England that Thackeray, Dickens and Cruikshank employed it as the center of a burlesque of 'Ancient Ballade' scholarship:

The poet has here, by that bold license which only genius can venture upon, surmounted the extreme difficulty of introducing any particular Turk, of assuming a foregone conclusion in the reader's mind, and adverting in a careless, casual way to a Turk unknown, as to a casual acquaintance. "This Turk he had___". We have heard of no Turk before, yet this familiar introduction satisfies us at once that we know him well.

As a philosopher of language, I find this delicious.

The name 'Suslan Pine' is of considerable antiquity: Kinloch's Ancient Scottish Ballads has it as 'Susie Pye'. The admirable Eunice Yeatts MacAlexander performs a comparable Virginian version on MTCD501-2, as did Alice Penfold on MTCD230. Here and elsewhere on this CD, Nimrod's pronunciation of names varies rather freely through his performances ('Baseman' is often rendered as 'Bayston', for example). We have not attempted to capture these variations in our transcriptions.

There lived a man, a man of honor,

Noble man of high degree

Who could nor would not be contented

'Til he sailed a voyage all over sea.

He sailed east and he sailed west

Sailed all near some Turkish shore

There he was caught and put in prison

For seven long years to stay or more.

They bored a hole through his left shoulder

Tied him to some ostrich(?) tree

They threw him in to a dungeon cell

Where daylight he might never see.

And this old king he had a daughter

Noble daughter of a high degree

She stole them keys to her father's prison

And vowed Lord Baseman she'd set free.

She said, "Honey, have you land or have you living

Have you living of a high degree?

What would you give to this Turkish lady

Out of these prisons would set you free?"

"Honey, I've got gold and I've got silver

I am living of a high degree

But I'd give my all to a Turkish lady

Out of these prisons would set me free."

She took him to her father's parlour

Called for a glass of strongest wine

Every health she drunk unto him

Saying "Lord Baseman I wish you was mine."

Suslan Pine she had a ship

Set it floating all on the deep

She shipped Lord Baseman across the sea

And wished him safe in his own country.

She said "I've got a bargain to make with you

You wed no woman nor me with no man

When seven long years has passed and over

Then I'll cross these raging mains."

Then seven long years had passed and gone

And the eighth they were returning on

She took her gold staff in her hand

To seek Lord Baseman in that foreign land.

She traveled 'til she came to Lord Baseman's dwelling

There she rung most modestly

"Who's there, who's there?" cried a proud young porter

"That knocks so makes these whole valleys ring?"

"Is this your place, Lord Baseman's dwelling?

Or is your noble lord within?"

"Yes, oh yes," cried this proud young porter,

"But he's just this day took a new bride in."

"Go ask him for three cuts of bread,

One bottle of the most strongest wine

Ask him if [he] do not remember

Who freed him from them cold iron bounds?"

Away this proud young porter ran

Fell upon his bended knee

"I'll bet, I'll bet," Lord Baseman said,

"Sweet Suslan Pine done crossed the sea"

She had a gay gold ring on every finger

Round her middle gold diamonds three

She got gold enough around her neck

To buy your bride and her company.

Lord Baseman risen from his table

Table leaves he's split in three

"Yonder stands the most fairest damsel

That my two eyes did ever see."

"Curse Suslan Pine", the old man said,

"Curse Suslan Pine from across the sea

Would you forsake your new wedded little wife

For that Suslan Pine from across the sea?"

"Old man, old man, I married your daughter

She is none yet worse to me

She came to me in a horse and buggy

She can ride back home all in her courtship free."

Took Suslan Pine by her lily white hand

Led her over the marble wall

Married two wives in the morning soon

Sweet Suslan Pine at twelve o'clock at noon.

2. My Pretty Little Pink (Roud 735). These floating quatrains seem to be fairly well known, although often confused in the folk song books with Fly Around My Pretty Little Pink and an apparently unrelated play party tune (echoes of which trace to Robert Burns!). The late Hessie Cruise Scott once told me that Tom Ashley used to sing the present song in a very drawn-out fashion at folk gatherings in the 1930s (presumably at the celebrated White Mountain Festival in which Mrs Scott's family were prominent participants - see David Whisnant, All Things Native and Fine). Insofar as I am aware, Ashley never recorded the piece despite the fact that the air nicely suits his 'sawmill' mode of banjo playing. I D Stamper recorded the tune as a dulcimer air on New World LP 226. Dellie Norton includes the opening verse in her pretty version of Black is the Color of my True Love's Hair on MTCD504 and George 'Shortbuckle' Roark from Pine Mountain, Kentucky recorded a related piece on banjo as I Truly Understand on an early 78. Randolph, Ozark Folk Songs, reports a version that has become elided with the hillbilly blues complaint, A Dollar is All I Crave.

Oh, you pretty little pink

Come and tell me what you think

You've been a long time making up your mind.

Oh, I really understand

That you want another man

Honey, how can your heart be mine?

Well you caused me to weep

And you caused me to mourn

Honey, you caused me to leave my home.

You caused me to walk

Them long lonesome roads

That I never did walk before.

Repeat verse 1 and 2

3. The City Four Square (Roud 12601). This central imagery traces to Revelations 21.16-25: 'And the city lieth foursquare … for there shall be no night there'. It probably derives from the 1899 gospel song No Night There, with lyrics by John R Clements and music by Hart Pease Danks (who also composed Silver Threads Among the Gold). However, the burden of Nimrod's verses are rather different than the original, so this may represent an independent versification of Revelations 21. As often happens with 'folk' recompositions of this sort, a rather standard gospel text has become retrofitted to suit the cycling 'mother...father..sister' repetitions characteristic of the 'brush arbor' songs from America's 'Great Awakening' era. Horton Barker sings a fuller version of Nimrod's song on Folkways FW 2362.

I am going to that city

Where them lights are hanging high

I am going where no troubles cannot come.

Will you meet me there, my father,

In that city that lies four square,

And we'll all be together over there?

I can see them pearly gates open,

I can see my savior's hand,

I can hear his tender voice pleading "Come,

Come up here my little children

To the city that lies four square

And we'll all live together over there."

Repeat with 'mother' for 'father'.

4. Sweet Rosie (Roud 12602). Boy, here is one whose source I missed when I programmed the original LP. It is, in fact, a scaled down and melodically much altered version of a George Jones song from 1962 called Open Pit Mine, written by one D T Gentry. I, in fact, have owned this record for many years but didn't suspect any connection until Mike Yates pointed it out to me. If Nimrod had sung more of the piece within its original contours, it would have been evident from internal clues that this was likely a product of 'the Folk Era' fashion of song writing; it is curious to observe the specific elements that caught Nimrod's fancy. He also sang it to me within a block of genuine fragments from British tradition.

Well, I caught my sweet Rosie in her rendezvous

She were a-hugging and kissing with somebody new

She were hugging, she was kissing, and having her time

On the money I made in that open pit mine.

Well, I pulled my revolver, shot her dead at my feet

Pulled my revolver and I shot her down

For hugging and kissing and having a time

I buried sweet Rosie in that open pit mine.

5. Lord Daniel (Child 81, Roud 52). Three good American versions of this surprisingly popular ballad (which Child called Little Musgrave) can be heard on Musical Traditions: Eunice Yeatts MacAlexander, and Cas Wallin on MTCD503-4 and Mary Lozier, MTCD505-6. Nimrod's version is unusual in that Mathie Groves unexpectedly wins the concluding fight with Lord Daniel. I find it odd - but charming - that Nimrod (or his source) would have remembered such a long song with fair accuracy, yet forget how it was supposed to end! Some other good American versions: Joseph Trivett, Folk-Legacy 002, Jean Ritchie, Folkways 2302 (probably displaying some of the 'literary' influences that I discuss in track 11).

Well, the first come down was dressed in red

The next come down in green

Next come down was Daniel's wife

Fair as any queen, queen,

Fair as any queen.

"May I go home with you, little love,

Home with you tonight?

I can tell by the rings you wear

You are Lord Daniel's wife, wife

You are Lord Daniel's wife"

The little footpath was standing by

And he heard every word that was said

"If I don't die 'fore the break of day

Lord Daniel hear of that, that,

Lord Daniel'll hear of that."

Well, he had about sixteen mile to go

Eight of them he run

Run 'til he came to the broken down bridge

Fell to his breast and he swum, swum

Fell to his breast and he swum, swum

Rattled at the door and she rung

Rattled at the door and it rung, rung

Rattled at the door and it rung.

"What is the matter, my little footpath,

What is the matter now?"

"Another man's in the bed with your wife

And both their hearts is one, one

Both their hearts is one."

Well, he called his army to his side

Told them for to go.

They threw them bugles to their mouths

They began to blow, blow,

They began to blow.

"Get up, get up my own true love,

You better get up and go.

Lord Daniel's coming home this night,

I can hear them bugles blow, blow

Hear them bugles blow."

They began to hugging and a-kissing,

They both fell off to sleep.

When they awoke their hearts was broke

Lord Daniel was at their feet, feet

Lord Daniel was at their feet.

"Get up, get up, little Mathie Grove,

Fight me for your life."

"How can I fight you for my life,

You two brand new sword,

Me not much as a pocket knife, knife

Not much as a pocket knife?"

"Oh yes, I have two brand new swords,

The best I'll give to thee."

And the very first lick Lord Daniel took

Brought Mathie Grove to his knee,

And the very first lick little Mathie Grove took

He destroyed Lord Daniel's soul, soul,

He destroyed Lord Daniel's soul.

6. Remember What You Told Me, Love (Roud 564, Laws P18). The first two verses of this stem from the old broadside that Steve Gardham discusses on this site under the heading of The Distressed Maid on the MT site. The song (usually as Last May Morn or some such) seems to have been popular along the West Virginia/Kentucky border and a fuller version by Mary Lozier can be heard on MTCD505-6, where I annotate some of its local particulars more fully. Bradley Kincaid included a version of this song (as Lord Bateman) in a booklet entitled My Favorite Mountain Ballads and Old Time Songs that he sold on his radio show at WLS in the early 'thirties. It circulated very widely but the various versions of the song that I encountered in the field are lyrically rather dissimilar. Nimrod's concluding verse has plainly wandered in as a vagrant lyrical cluster.

"Remember what you told me, love

Remember what you said;

Remember what you told me, love

Lying across the bed?

You promised that you'd marry me

Make me your lovely bride."

"If ever I made such promise to you

It's more than I can do

I never intend to marry no girl

As easy fooled as you."

Well, I ofttimes heard my grandma say

She were not bad to lie

To roll all in a pretty girl's arms

Would bring the dead to life

Bring the dead to life.

7. Rock the Cradle and Cry (Roud 12605). Once again, Steve Gardham discusses some of the early antecedents of this fragment under the heading Rock The Cradle, John in MT. In the United States, these sundry predecessors at some point divided into at least three groups with little subsequent interaction between them: (1) this song; (2) The Old Man Rocking the Cradle group, which eventually became transmogrified into the well-known Get Along Little Dogies and (3) the comic stage song Rock All the Babies to Sleep, which was recorded frequently on 'hillbilly' records (Jimmie Rodgers, Riley Puckett), sometimes emerges as a dance waltz (Lonnie Robertson on Rounder 0375) and has even entered the English Gypsy repertoire - Doris Davies sings it on MTCD345-7. In its most common US form, the present song is often called Red Rocking Chair (Dock Boggs recorded a celebrated variant as Sugar Babe) with lyrics such as:

Who'll rock the cradle, who'll sing this song?

Who'll rock the cradle when I'm gone?

As such, it remains a favorite of bluegrass musicians, possibly tracing to an excellent early recording by Charlie Monroe.

Go rock the cradle, go rock the cradle

Go rock the cradle and cry.

Go rock the cradle, go rock the cradle

Go rock the cradle alone.

Many man's rocked another man's babe

He thought he was rocking his own.

Go rock this cradle, go rock the cradle

Go rock this cradle and cry.

8. Coal Black Mining Blues (Workman) (Roud 12603). I am somewhat puzzled by this song as it appears (through its 'I got the blues, got the blues Lord, Lord' refrain) to be constructed upon the framework of The Alcoholic Blues, a rather sophisticated 1919 composition by Edward Laska and the well-known composer Albert Von Tilzer. It was popularized soon thereafter by Billy Murray and entered tradition as both a song (it appeared on several early 'hillbilly' records) and as a virtuoso harmonica piece (by the Grand Ole Opry's Deford Bailey and Sonny Terry, inter alia). This Tin Pan Alley production also served as the direct model for a well-known labor song Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues, originating in the textile strike of 1937. The latter was recorded in the 1950s by Pete Seeger and appeared in the well-known collection Songs of Work and Freedom compiled by Joe Glazer and Edith Fowke. As such, the song would have been occasionally performed by the youthful labor organizers with whom Nimrod became acquainted in the 1960s and may have been the present song's inspiration.

However, the lyrics of Coal Black Mining Blues strike me as less didactic than Nimrod's more overtly 'protest' material (such as Mother Jones' Will and Black Lung Song), so I think it more probable that Nimrod composed this piece for the amusement of his co-workers long before he began composing songs for this newer audience (he told me that he often sang for the amusement of his fellow miners while they all ate their lunches sitting on the tracks underground). Insofar as I could determine from my own interviews, the Appalachian people were generally conservative about musical innovation and frequently viewed 'composing a song' as simply a matter of claiming found material as a performance speciality. In this mode, Nimrod told me that "I made that Stone that was Hewed Out of the Mountain song", despite the fact that every major ingredient within his piece is easily documented within earlier tradition. I think that such claims (which one frequently encountered amongst country singers - see Oh, Death below) usually reflect an alternative understanding of 'composition,' rather than prevarication. Indeed, the great mountain composer Sarah Gunning told me that she was inspired to write in 'protest' mode only by the labor organizer community in which she and her siblings became enmeshed in the 1930s; she had not found such 'composition' especially natural before or after.

But the framing of gentle satires upon the foibles of ones neighbors and co-workers plainly represented a long-standing mountain custom within Nimrod's region (with the proviso that one needed to remain wary of the wounded pride of folks who carried pistols). A good exemplar of such a modest ditty can be found on MTCD505-6 (Natural Bridge Song). Much of Nimrod's piece strikes me as of this same amiable nature. Insofar as I am aware, Nimrod's first recording consisted of of this song b/w 42 Years on 45 rpm record issued in 1970 on Dillon's Run Records. Quite possibly Nimrod may have volunteered his old coal mining song - he was never shy - at some union rally in the 1960s and that is how his late life 'musical career' commenced.

To be sure (as I discuss more fully in the notes to MTCD505-6), street singers such as J W Day and Blind Alfred Reed circulated freshly composed material over large geographical regions areas through serving as itinerant 'singing newspapers' at county court days and similar gathering points. Major events within the mining community would have been regularly reflected within these compositions, some of which did enter tradition (Nimrod knew Day's House Burning in Carter County, for example). I think that accurately framing a better picture of how song conservatism and song innovation interacted within rural regions before outside world models of 'composition' became familiar to them would represent a worthwhile scholarly endeavor (the many well-intentioned narratives found in books of a Hard-Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit Folks ilk cannot be regarded as descriptively accurate in these regards).

I might also observe that I did a fair amount of recording work in the mid 1990s with Snake Chapman and his friends, many of whom had labored in the Kentucky mines just across the Big Sandy River from Chattaroy (Bert Hatfield, in fact, worked in the big Williamson train yards that ran just in front of Nimrod's door, and witnessed in many of the pictures I took of him). Snake's group were all familiar with Nimrod from local television and allied events (although I don't think that any of them knew him personally). And it was clear that they were somewhat bemused by these appearances, generally in the vein (if I understood them correctly) of "Oh, he was just acting a fool for the hippies." Self-conscious efforts to reacquaint the Appalachian people with their traditional music through public concerts in that era rarely struck the right tone, I think, alternating between the excessively solemn ('a cappella ballads') and the excessively stentorian ('protest songs'). A natural extrovert like Nimrod loved the attention he received within such forums, but a humbler soul such as Bert Hatfield found such settings off-putting, although he would have dearly enjoyed hearing Nimrod recall some of his grandfather's forgotten songs within the intimacy of a kitchen or living room.

Chorus: I got the blues, got the blues Lord, Lord,

Coal black mining blues.

Went to my place and I peeped in,

Slate in the water up to my chin.

Chorus

I looked at old Jim, Jim looked sad:

"The worst darn place that I ever had."

Chorus

Sent me to the office to look at the roll

Children, counted up nine dollars in the hole.

Chorus

Tell Enos on the parting, half past four

Herb's in the heading and he wants four more.

Chorus

Bascom at the bottom, dipping up sand

Along comes Shorty, says "I got another man."

Chorus

Herb on the tipple, singing a song

Get going, Herbie, for winter's coming on.

Chorus

9. Mother Jones' Will (Workman) (Roud 12600). In the autobiographical statement above, Nimrod supplies his own narrative of the calamitous events in 1920-1 that transpired within West Virginia's Mingo and Logan Counties in the course of the UMW's early attempts to unionize the Appalachian coal fields. After these struggles, the UMW relaxed attention on the area, leaving a lapse in organizing that was filled in the early 1930s by more radical organizations such as the NMU (with which Jim Garland and Sarah Gunning were associated). As a young miner (starting at age 15), Nimrod undoubtedly witnessed some of the events he described, whereas other aspects merely represent non-personalized reflections on the era (although phrased in the voice of direct acquaintance - a characteristic I often encountered in Appalachian informants). Certainly, some of Nimrod's details about Mary Blair 'Mother Jones' reflect miners' folklore, rather than her true biography as we now have it. Nimrod's tune is approximately that of John Henry.

Well, I'm going to that Hart's Creek Mountain

Going back to old Blair Mountain Hill.

I'm a-gonna fight for the Union

'Cause I know it's Mother Jones' will

And I know it's Mother Jones' will.

Well, our children were laying in the tents

They were laying upon the quilts

While the thugs were a-rambling through their tents

Pouring kerosene in their milk

Pouring kerosene in their milk.

Repeat verse one

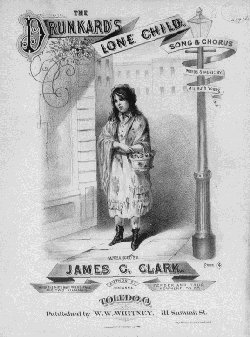

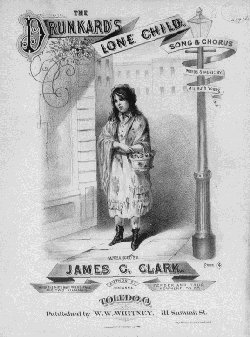

10. The Drunkard's Lone Child (Roud 723). Several nineteenth century songs share this title and (in part) the opening verse. One of these (often called Little Bessie, although it is not the song below) expresses temperance concerns in the manner:

We were so happy till father drank rum;

Then all our sorrows and troubles begun.

Mother grew paler and wept every day;

Baby and I were too hungry to play.

Slowly they faded and one summer night

Found their sweet faces aIl silent and white

And with big tears slowly dropping I said,

"Father's a drunkard and mother is dead."

(Cf. Sigmund Spaeth, Weep Some More, My Lady). In Nimrod's version, like Dock Boggs' related text (Folkways SFW-40108), the loss of a mother frames the central emotional focus. As such, the words and music are credited to Mrs Ruth Young and published in 1879.

All alone, all alone, my friends they've all fled

My father's a drunkard, my mother she's dead

I'm a poor orphan child and I wander and weep

For the voice of dear mother to sing me to sleep.

Lord have pity, look down on a poor orphan child

In pity look down and hasten to me

And take me to dwell with mother and Thee.

Last night in a dream Mother seemed to draw near

Last night in a dream she seemed to draw near

To hug (?) and kiss me as if she were here.

To hug and she kissed me and folded my brow

To hug and she kissed me then folded my brow

And whispered, "Sleep on, I'm watching you now."

Spring time is near and the birds are so glad

They sing in the springtime while their songs are so sad

They sing in the springtime while strangers pass by

The voice of sweet mother no more is nigh.

11. What is that Blood Stain on your Clothes? (Child 13; Roud 200). Given its frequent appearances within Victorian poetry collections, it is rather surprising that more examples of Bishop Percy's (apparently) reconstructed Edward don't show up within American tradition. I have often been surprised at the handiwork of such literary influences within the most remote parts of the mountains (see Jim Garland's Land of Yahoe on Rounder 8041 for an intriguing example). Given the local patterns of literacy, I wonder whether such 'polite society' influences might have sometimes proved more potent in their effects upon Appalachian tradition than the cheaply printed songsters and broadsheets that plainly influenced repertory in New England and the Old Country. Nimrod substitutes a typical Appalachian air for the more common 'that plowed the field for me, me, me' setting and his version also drains most of the dramatic suspense from the story, through telegraphing the true source of the blood stains early in the song. The result is a formulaic recitative, not unlike Hangman, Slack Your Rope. As is witnessed by the many similarly structured gospel songs in his repertory, Nimrod dearly loved this form of cyclical repetition. At some point I plan to reissue the version I recorded from Almeda Riddle (Rounder 0083) on MT.

"What is that blood stain on your clothes

The blood that looks so red?"

"That is the blood of my hunting hound,

I killed him yesterday."

"As to the blood of your hunting hound,

It could not look so red.

It must have been the blood of your own true love,

You killed her yesterday."

"Oh, what is that blood stain on your clothes

That stain it looks so red?"

"That is the blood of my little white horse,

I killed him yesterday."

"As to the blood of your little white horse,

It could not look so red.

Must be the blood of your own true love,

You killed her yesterday."

"Now, what is that blood stain on your clothes

That stain that looks so red?"

"That is the blood of my own true love

I killed her yesterday down in the old pine grove."

12. Working on this Railroad (Roud 12606). This little ditty occasionally shows up as a good banjo song - cf. Rufus Crisp in the Library of Congress and George Gibson on the June Appal CD, Last Possum Up the Tree. The first stanza often appears in the widely spread 'blues ballad' Been All Around this World (Laws E43) - cf., Justice Begley's great recording for the Library of Congress.

Working on this old railroad,

Mud up to my knees

Working for my pretty little love

She's so hard to please.

Working on this old railroad

Dollar and a dime a day

A dollar for my blue-eyed girl

I go a dime to throw away.

Repeat first verse

13. Black Lung Song (Workman) (Roud 12599). I never encountered anyone who had worked for very long in the coal fields who hadn't developed some measure of this dreadful condition. Nimrod's personal testimony played a significant role in the 1970s' efforts to gain better compensation for this work-related illness.

Went into my place this morning

And I got down on my knees

I couldn't load no coal

All I could do was cough and wheeze.

Chorus: Got that pneumoconiosis, black lung too

You get one, you've got the other

Either way you lose.

Well, I went to see my doctor

And he looked me over twice

"You got something, Nimrod,

Sure gonna take your life

Chorus

I'm an old coal miner

And I eat dust all my life

I'm too old to learn a new trade

What can I tell my wife?

Chorus

I got thirteen little children

And they've all got to eat

No clothes upon their back

No shoes upon their feet.

Chorus

When I get up in heaven

St Peter's gonna cry

When I tell him the reason

Poor Nimrod had to die.

Chorus

When I get up in heaven

Gonna hug St Peter's neck

When he tells old Paul and Silas

"Give Nim his black lung check.

Chorus

14. I Want to Go Where Things Are Beautiful (Roud 12607). I've found no other trace of this gospel song (which serves as the title number upon the recent issue of Mike Seeger's recordings of Nimrod), although it is clearly framed upon Revelations 21:18: 'And the building of the wall of it was jasper: and the city pure gold, like unto clear glass.' I wouldn't be surprised if it couldn't be found in one of the cheap gospel songsters that were widely distributed along the West Virginia/Kentucky border (such as Billup's Sweet Songster).

I want to live so I'll be ready

On that day when Jesus comes

So that I could go home with Him

And I'll be left behind life's .......

I wanna go where things is beautiful

Where I know I'll never grow old

Where them walls are all made of jasper

And them streets are all paved with gold.

I want my love, wants to go with me

To that mansion bright and fair

Where there'll be no separation

Children, won't we all be glad?

15. Biler and the Boar (Child 18, Roud 29). Child 18 has this as Sir Lionel; it is more frequently called Bangum and the Boar in the US and is often sung in a burlesque vein, as here. The Kimble Family of Virginia recorded Wild Hog in the Woods as an instrumental tune on several occasions (e.g. County 746) and this setting has become popular in the revival. Once again, a nice parallel version by Eunice Yeatts MacAlexander is available on MTCD501-2 and the old AAFS album L57 contains two nicely contrasting versions. Nimrod sings this in duet with his daughter Phyllis on June Appal JA 001.

Biler went to the wild boar's den, quiloquay

Biler went to the wild boar's den,

There laid the skulls of a thousand men

Quiloquay, quayquarm, quattledown.

Biler made him a wooden knife, quiloquay

Biler he made him a wooden knife

Swore he'd put an end to the wild boar's life

Quiloquay, quayquam, quattledown.

Here come the wild boar cutting out a slash, quiloquay

Here come that wild boar cutting out a slash

Tearing down hickory, white oak and ash

Quiloquay, quayquam, quattledown.

16. The Devil and the Farmer's Wife (Child 278, Roud 160). This old humorous song (Child: The Farmer's Curst Wife) is extremely popular in America and pops up in a wide variety of settings, including versions with whistling refrains (see Hobert Stallard on MTCD505-6 and his daughter Nova Baker on Rounder 8047)). Horton Barker's Library of Congress version (which resembles the 78 recording by Bill and Belle Reed) is justly celebrated (a later version appears on Folkways 2362). Texas Gladden and Jean Ritchie supply nice versions on Rounder 1800 and Folkways 2302 respectively.

"Hey, old devil, don't you take my son"

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

"There's work on the farm that has to be done"

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day.

"It's not your oldest son I want

It's your nagging old wife that I'll take with me"

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Come a rum dum diddle I day.

Well he carried her down to the forks of the road

Come a rum dum diddle I day

Said "Hey old woman you're a heck of a load"

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Come a rum dum diddle I day.

Three little devils come around with a ball and chain

She upped with a shovel, knocked out their brains

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Come a rum dum diddle I day.

Three little devils peeped over the wall

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Rum dum diddle I day

Three little devils peeped over the wall

Said "Take her back Daddy, she's a-killing us all"

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Come a rum dum diddle I day.

Well, he picked her up all on his back

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Come a rum dum diddle I day

Picked her up all on his back

Looked like Tom Tinker went wagging her back

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Cum a rum dum diddle I day.

Says "Here's your wife and I wish you well

She killed all my children and she tore up Hell"

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Come a rum dum diddle I day.

The old man took off around the hill

Come a rum dum diddle I day

Said "The devil won't have her

I'm damned if I will."

Come a rum dum diddle I diddle I day

Come a rum dum diddle I day.

17. Loving Henry (Roud 47, Child 68). Child has this as Young Hunting, but Nimrod's nomenclature is more common within America (sometimes as Lord Henry). The version that has been most commonly imitated within the revival derives from a 78 by Dick Justice of Logan County, West Virginia entitled Henry Lee (it was reissued on the celebrated Anthology of American Folk Music. Justice was an associate of Frank Hutchinson, whom Nimrod claimed to have known, although he could provide no details on their encounters. Jimmy Tarlton recorded another version on a hillbilly 78 and traditional American versions have been more recently recorded by Maggie Hammons Parker, Rounder 1504/05; Ella Parker, Folkways 3809 and George Landers, Rounder 0028. Here Nimrod employs the same tune as he used for The House Carpenter on MTCD505-6.

"Come in, come in, Loving Henry," she said

"And stay all night with me.

I'll make your bed as pure as gold

And white as ivory."

"No, I can't come in, nor I won't come in

Nor stay all night with you.

That girl that I left in New Orleans,

She will think that I proved untrue."

But he leant over across the fence

To take a kiss or two

And a penhold knife she held in her hand

She pierced him through and through.

She dug a grave in her own backyard,

She dug it all six by three.

"Just stay right there, Loving Henry," she said,

" 'Til the meat drops from your bones.

That girl that you left in New Orleans

Think you a long time coming home."

"Fly down, fly down, you pretty little bird,

Come and rest upon my knee;

I'll make your cage as pure as gold

And hang her on yon willow tree."

"I can't fly down nor I won't fly down,

Nor rest upon your knee.

A girl that would murder her own true love

Would kill a little bird like me."

"If I had my cedar bow,

Arrow and my string,

I'd shoot a dart slap through your heart

No more you would sit and sing."

"If you had your cedar bow,

Arrow and your string

I'd fly to the top of yon tall hill

There I would sit and sing."

18. Darling Cory (Roud 5723). Dick Justice also recorded this well-known banjo tune on 78, as did Buell Kazee, B F Sheldon, Dock Boggs and many other great artists from Nimrod's general corner of the mountains. The Monroe Brothers popularized a souped-up arrangement amongst bluegrassers.

Wake up, get up, Darling Cory

What makes you sleep so sound?

Them highway robbers coming

Gonna burn your building down.

Get up, get up, Darling Cory

Go and bring to me my gun

Them highway robbers coming

Gonna die before I run.

The last time I seen Darling Cory

She had a dram glass in her hand

She were drinking down her trouble

She were courting another man.

Next time I saw Darling Cory

She's on the banks of yon deep blue sea

With a forty-four buckled around her

And a banjo on her knee.

Go dig a hole, dig a hole in the meadow

Go dig a hole, dig a hole in that ground

Dig a hole, dig a hole in the meadow

I'm gonna lay Darling Cory down.

19. The Stone That Was Hewed Out The Mountain (with Molly Workman) (Roud 23350). The imagery of this song derives from a rather strange passage in Daniel 2:34-35 where Daniel interprets a strange dream of King Nebuchadnezzar as follows:

Thou, O king, sawest, and behold a great image. This great image, whose brightness was excellent, stood before thee; and the form thereof was terrible. This image's head was of fine gold, his breast and his arms of silver, his belly and his thighs of brass, His legs of iron, his feet part of iron and part of clay. Thou sawest till that a stone was cut out without hands, which smote the image upon his feet that were of iron and clay, and brake them to pieces. Then was the iron, the clay, the brass, the silver, and the gold, broken to pieces together, and became like the chaff of the summer threshing floors; and the wind carried them away, that no place was found for them: and the stone that smote the image became a great mountain, and filled the whole earth.

This piece has been recorded a number of time by the great gospel ensembles such as the Golden Gate Quartet, The Silver Leaf Quartet and so on. These rather jazzy versions are more lyrically varied than Nimrod's and feature a release:

Well, meet me, Jesus, meet me

Meet me in the middle of the air

'Cause now if these wings should fail me

Lord, I want to hitch on another pair.

As noted above, Nimrod told me that he had 'composed' this song and his daughter Phyllis filed a copyright claim on the piece (under her own name). One might have presumed that Nimrod's 'composing' consisted of largely of reframing the song to highlight the Great Revival repetitions discussed above (Nimrod sang many songs of this type - cf. MTCD507-8 for more). However, Keith Whitley and Ralph Stanley independently recorded a Looking for That Stone that follows the same pattern, so Nimrod's form of 'personalization' must have occurred along more subtle contours than that.

I'm looking for that stone was hewed out of the mountain

Looking for that stone that come rolling down from Babylon

Looking for that stone was hewed out of the mountain

Tearing down the kingdoms of this world.

I'm glad I found that stone was hewed out of the mountain...

My mother had that stone was hewed out of the mountain...

I'm looking for that stone was hewed out of the mountain...

My Jesus is that stone was hewed out of the mountain...

20. Little David Play Your Harp (with Molly Workman) (Roud 11831). This wonderful spiritual/revivalist song has been widely recovered from both white and black tradition since the mid nineteenth century and has lately earned an improbable popularity as a camp song and through anaemic arrangements for high school choirs (for an instructive contrast, compare the great King recording by Brother Claude Ely, recorded at a revival meeting in Whitesburg, Kentucky in the early 1950s). The Workmans' version is quite unlike any I know, either the standard:

David was a shepherd's boy

Killed Goliath and he shouted for joy

or the odd, almost comic, piece about Noah known to Jim Garland and Sarah Gunning (cf. MTCD507-8). I imagine that this setting traces to Molly's Pentecostal church.

Molly Workman was a very pleasant woman but shy and very retiring during most of our recording work. I was glad that I managed to extract a few tunes from her, as her duets with Nimrod strike me as some of the most ingratiating material I obtained at that session.

There's Matthew, Mark, Luke and John

Jeremiah, Malachi, Stephen, Saint Thomas

Elijah and Moses, Zechariah and Joseph

Samuel and God knows how many?

Little David play on your harp

Play on your harp, Little David

Play on your harp.

Repeat

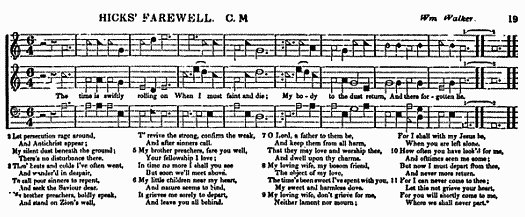

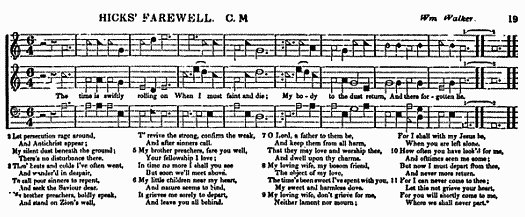

21. Brother Preacher (Roud 2869). Usually known as Hicks' Farewell, this plaintive song appears in William Walker's celebrated Southern Harmony with the head note: 'This song was composed by the Rev B Hicks, (a Baptist minister of South Carolina,) and sent to his wife while he was confined in Tennessee by a fever, of which he afterwards recovered.' According to John R Logan, (Sketches of the Broad River and King's Mountain Baptist Associations, Shelby, NC): 'Elder Berryman Hicks was born in Spartanburg County (now Cherokee County) July 1, 1778.' He 'intermarried' with Elizabeth Durham in 1799 and 'reared a large and interesting family.' He joined the State Line Church in 1800 and was soon licensed to preach. 'He was a great revivalist and went far and near with his great co-worker, Elder Drury Dobbins.' George Pullen Jackson (White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands) adds: 'Hicks died at Little Buck Creek, Spartanburg County, SC, on Jun 11, 1839.'

Nimrod's version omits the evocative opening stanza:

The time is swiftly rolling on

When I must faint and die,

My body to the dust return

And there forgotten lie.

along with Hicks' subsequent admonitions to his fellow preachers. Nimrod instead focuses his attention upon Hicks' concluding message to his wife and family, producing a net result that resembles that a love song more than a sermon. Other good recordings: Texas Gladden, Rounder 1702, Dillard Chandler, Folkways.2309. The version that Doc Watson sings to Gaither Carlton's plaintive fiddle on Folkways 40029 has become quite well-known within revivalist circles.

My brother preachers, boldly speak

Who stands on Zion's wall

Confirm the weak, revive the strong

And make their sinners call. [Usually: And after sinners call]

My loving wife, my bosom friend,

The object of my love,

How oft times have you looked for me

And oft times seen me come?

But now I must depart from thee

To never more return

Let not this parting grieve your heart,

Neither remain (?) or mourn.

For you can quickly come to me

Where we shall never part.

Dear Lord, a father to her be

And keep her from all wrong

That she may know and worship Thee

And lean upon Your arm.

My little babies, near my heart,

And nature seems to bear [usually: bind]

Dear Lord, a father to them be

And shield them from all wrong

That they may know and worship Thee

And lean upon Thine arm.

22. In the Pines (Roud 3421). Norm Cohen's celebrated Long Steel Rail provides an extensive head note on this complicated song cluster, based in part upon Judith McCulloh's earlier research. The piece's sundry motifs drift from one song to another, spilling over into Old Rueben, Them Rolling Mills is Burning Down, Nine Hundred Miles and many others. Cohen notes the curious fact that the best known prototype of this piece amongst revivalists - Leadbelly's Black Girl - appears to represent a feedback from the pages of Sharp's English Folksongs from the Southern Appalachians through the agency of some revivalist intermediary (a similar background lies behind the emergence of The House of the Rising Sun as a 'well known black folk song'). Asa Martin recorded an interesting version for me as a guitar parlor piece which I hope to issue someday. Nimrod's humming at the end shows an awareness of Bill Monroe's well-known bluegrass setting, although otherwise Nimrod's text seems to be his own.

Chorus: In the pines, in the pines

In the cold, cold pines

Lord, I shivered when the cold wind blow.

The longest train I ever saw

Run down that Georgia line

The engine passed at six o'clock

And the cabin rolled by at nine.

Chorus

The train run back one mile from town

And killed my girl, you know

Her head got caught in the driver's wheel

And her body I never could find.

Chorus

I asked my captain for the time of day

He said, "I threw my watch away."

Chorus

Little girl, little girl

What have I done?

You've turned your back on me

Took all of my clothes

Throwed them out of doors

Goodbye, little girl, goodbye.

Chorus

Well, a long steel rail

And a short cross tie

I'm beating my way back home.

Chorus

23. Newsy Women (Roud 641, Laws C19). As indicated above, the habit of framing satires upon the mildly rowdy exploits of ones friends or neighbors seems to have once been fairly common within the mountains, although I was only able to record one good specimen with a tune (Natural Bridge Song). Rarely, however, do such ephemeral pieces spread much beyond the community in which they were engendered. But the present ditty, which strikes me as completely comparable internally to such homemade compositions, has been obtained over an extremely large area, stretching from Canada (Folkways 4052) and New England, through New Jersey (Marimac 9200) and the mountain South and eventually out to Indiana (Folkways 3809). Why this has happened, I do not know, except that a fair rasher of 'Northern songs' (like The Jam on Gerry's Rocks) seem to have been carried southward through the lumber camps. Folk Songs of The Catskills lists a few songster citations from the 1880s (which I have not ben able to examine), so perhaps the song enjoyed some stage currency in that era. The piece, in its sundry variants, has a frustrating habit of citing tantalizing names for fiddle tunes (e.g. The Crippled Kingfisher) that have never been recovered from tradition!

Took my saddle one morning

And headed to the barn

I saddled up my old grey mare

Not meaning any harm.

Saddled up the old grey mare

Headed out to Barrow Hill

I expected one glass was empty, boys

Another was filled for me.

I met a kind old acquaintance

His name I won't tell at all

He told me that night, boys,

Where there's gonna be a ball.

They danced and they fiddled

About four hours long

They played "The Crippled Kingfish"

About four hours long.

I see the morning star, boys,

I believe it's time to go,

We'll go back to our plough, boys,

We'll whistle and we'll sing

We'll never be guilty, boys,

Of another such a thing.

Come all you newsy women

That scatters news about

Don't tell no tales upon us

We're bad enough without

Don't tell no tales upon us

To try to raise a fuss

You've been guilty of the same thing

Perhaps a whole lot worse.

24. Oh Death (Roud 4933). This well-known piece reveals some mild lyrical overlap with the English Death and the Lady (cf., Williams and Lloyd, Penguin Book of English Folk Songs):

My name is Death, cannot you see?

Lords, dukes, and ladies bow down to me

And you are one of those branches three,

And you fair maid, and you fair maid,

And you fair maid must come with me"

But such resonances can easily prove accidental, spawned by nothing more than a shared thematic. As such, the present song may be entirely American in origin but there is no doubt that it is fairly old and widely spread. In these respects, I had an interesting encounter with commercial music publishing a few years ago. Although variants of this song are fairly well known, the versions which have most influenced the revival are Dock Boggs' great version on Folkways 9025 and Lloyd Chandler's Conversation with Death on Rounder 0028 (I was co-producer on that project, hence my entanglement with Hollywood). The subsequent familiarity caused the Coen Brothers to solicit a somewhat bizarre version of the song from Ralph Stanley in the Hollywood film, Oh, Brother, Where Art Thou? The soundtrack from this film made a good deal of money and it happened that Lloyd Chandler had always told his family that A Conversation with Death was 'his song'. As such, I imagine that it was 'his song' in exactly the same sense that The Stone that was Hewed out of the Mountain was Nimrod's. But that consideration didn't keep a lot of folks from scrambling around trying to establish firm ownership of the piece (and, insofar as I can tell, for every other tune in the film - I also became marginally entangled with the Ed Haley fiddle setting for Man of Constant Sorrow). All this struck me as sad - we never found a suitable way to reward folk performers for their great contributions to our culture, and conventional copyright law only made matters worse.

Black and white versions of Oh, Death differ somewhat in tenor - good examples of the former can be heard from Vera Hall and Dock Reese (Folkways 2008 and Atlantic 82496), Bessie Jones (Rounder 8004) and the Pace Jubilee Singers on 78. I once spent an afternoon with the great Bahaman guitarist Joseph Spence and he slipped into a recitation of some of these verses apropos of nothing in particular. On her excellent Folk Legacy recording, Sarah Gunning told Archie Green of a time when her beloved mother Elizabeth happened to sing this song while gathering herbs in the woods. Some moonshiners mistook her for an apparition and fled in terror. Nimrod dearly loved to 'act out' his songs with his hands and facial expressions (a policy he probably borrowed from the little medicine shows that often visited the mountain communities in the 'twenties and 'thirties). Performed in this manner, Oh Death was likely to have proved popular in his performances for revivalist audiences in later years. Nimrod sings this in duet with his daughter Phyllis on June Appal 001.

Chorus: Oh Death, Oh Death,

Won't you spare me over for another year?

What is that I can't see

Icy hand's got a hold on me?

I am Death, come here for your soul.

Leave your body and leave it cold.

Chorus

I am Death and I wish you well

And I hold the keys to Heaven and Hell.

Chorus

Gonna take the skin

Right off of your frame

And the earth and the worm

Both have their claim.

Chorus

Death, Oh Death, consider my age

Please don't take me in this stage.

Chorus

25. The Carolina Lady (Laws O25, Roud 396). According to Malcolm Douglas:

The underlying story is quite old, and appeared in Les Mémoires de Messire Pierre de Bourdeilles, Seigneur de Brantôme (1666, Discours 10e). Schiller based his Der Handschuh (1797) on it, as did Browning his The Glove, and Leigh Hunt, his The Glove and the Lions. De Brantôme asserted that the original event took place in the reign of Francis I (1515 - 1547). (See Journal of the Folk Song Society, V (20) 1916 258-60). In literary forms, the victorious suitor, having recovered the glove, rejects the lady for her pride and presumption; but as a popular song it has acquired a conventional happy ending.

As an additional antecedent, Duncan Emrich (American Folk Poetry) cites an eighteenth-century broadside entitled The Distressed Lady, or a Trial of True Love. In Five parts (with fifty-five stanzas). American singers are often befuddled by the military identification of the two brothers, which appears in an old broadside as:

One of them bore a captain's commission,

Under the command of bold Colonel Carr

The other he was a noble lieutenant

On board the Tiger Man of War.

Nimrod, however, simply skips the problematic verse. He employs the usual lower strain to Wayfaring Stranger as his air; I believe that Basil May's well-known version on Library of Congress AFS 001 r essentially represents the same setting adapted to the major chords of his guitar playing. A good version by Doug Wallin can be found on MTCD503-4 and his cousin Dillard Chandler sings similar versions on both Folkways FA 2418 and Rounder 0028.

Down in Carolina lived a lady

She were most beautiful and gay

All determined to live a lady

And no young man could her betray.

Up rode two loving young brothers to see her

Saying "Pretty fair maid, will you marry me?"

"No, kind sir, it were never intended.

Only one man's bride could I ever be.

But meet me here tomorrow morning

Upon this case we will decide."

Then she called for a horse and buggy

It were ready at her command.

Over hills and woods she rambled

Until she came to the lion's den.

And when she seen them both a-coming

She threw her fan in that lion's den

Saying, "Which of you shall gain this lady,

Will return to me my fan again?"

Up stepped this brave bold lieutenant,

"Madam, I am a man of war

Madam, I'm a man of honor,

But I'll never lose my life for love."

Up stepped this brave bold sea captain,

"Madam, I am a man of war

Madam, I am a man with honor,

I'll return to you your fan again."

Down into the lion's den he wandered,

Until he tore it out again.

And when she seen her lover coming

And no harm to him were done

She fell likewise all in his bosom

Said, "Here's that prize that you have won."

Up stepped this brave bold lieutenant,

Says "Madam, I am a man of war

But over hills and woods I'll ramble

And my face you'll see no more."

26. Little Bessie (with Molly Workman) (Roud 4778). See my comments on this well-beloved song in connection with Buell Kazee's stunning performance on MTCD507-8. It was composed circa 1875 by R S Crandall and W T Porter and remains popular within bluegrass circles. The Workmans' version is comparatively truncated in comparison to other versions which, in Mary Lozier's words, "have a story to tell and take their time a-getting there." As noted above, another Little Bessie is occasionally found in tradition.

Hug me closer, closer, Mother

Put your arms around me tight

For I'm cold and tired, dear Mother,

And I feel so strange tonight.

All that day while you were working

Just before the children came

While the room was very quiet

I heard someone call my name.

"Come up here, my little Bessie,

Come up here and live with me

Where no little children suffer

Suffer through all eternity."

All at once the window opened

On a hill of lambs and sheep

Some far by the brooks a-drinking

Some were lying fast asleep.

Then at once the window opened

On a hill so bright and fair,

It were filled with little children

And they seemed so happy there.

They were singing oh so sweetly,

Sweetest song I ever heard

Song that they were singing, Mother,

Sweeter than a little bird.

All at once the window opened

One so bright upon me smiled

Then I knew it must be Jesus

When He said, "Come here, my child."

"Come up here, my little Bessie

Come up here and live with Me

Where no little children suffer

Suffer through all eternity."

Credits:

Produced by Mark Wilson.

Recorded in Chattaroy, West Virginia, March 1976, by Mark Wilson and Ken Irwin.

Tracks 1-18 originally issued in 1976 as Rounder LP 0076. Tracks 19-26 are new to this production.

Annotated by Nimrod Workman and Mark Wilson.

Song transcriptions by Danny Stradling.

Photography by Mark Wilson.

Nimrod's original songs are © Nimrod Workman/Happy Valley Music, BMI.

Special thanks to the late Phyllis Boyens-Litwak, Ken Irwin, Bill Nowlin and to the logistical support that Rounder Records provided in most of my active years of field recording. Some of the interview material previously appeared in Golden Seal Magazine.

Thanks to Mike Yates for assitance on the tune notes.

A Musical Traditions Records production

© 2011

Article MT264

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 1.5.11

I was doing all that for fifty cents and a supper of cornbread and sweet milk, so I says to myself, "Why should you be loading eight and nine cars of coal for him, with him getting three dollars out of it and you only getting fifty cents?" Finally I buckled up to the mine foreman and explained the thing to him. He says to me, "But you're too young to work in the mines; I can't give you any checks."

I was doing all that for fifty cents and a supper of cornbread and sweet milk, so I says to myself, "Why should you be loading eight and nine cars of coal for him, with him getting three dollars out of it and you only getting fifty cents?" Finally I buckled up to the mine foreman and explained the thing to him. He says to me, "But you're too young to work in the mines; I can't give you any checks."