A collection of shorter pieces on subjects of

interest, outrage or enthusiasm ...

|

Enthusiasms No 45 A collection of shorter pieces on subjects of interest, outrage or enthusiasm ... |

Come all you jolly sailors bold,Although well-enough known through an orchestral version by Sir Henry Wood, played at each last night of the 'Proms', the song known as The Arethusa is not one found in traditional song repertoire; but yet has a fascinating history which does impinge. Even in its first manifestation as noted here it was an unlikely serenade for a hero to sing under his love's window (he was, granted, a naval hero when naval heroes abounded) but such were the exigencies of popular opera in its time … the lover may well be supposed to be giving his own ego a boost by a tale of derring-do.

Whose hearts are cast in honour's mould,

While English glory I unfold,

Huzza to the Arethusa!

She is a frigate tight and brave,

As ever stem'd the dashing wave;

Her men are staunch to their favourite launch,

And when the foe shall meet our fire,

Sooner than strike we'll all expire,

On board of the Arethusa.

The words of the piece under review were penned by a Prince Hoare (not a titled name) who was born in Bath in 1755 and was, above all, a painter of portraits and historical pictures. He, nonetheless, contrived to produce a score of plays - all forgotten - in eleven years. He died in Brighton in 1834.

'Twas with the spring fleet she went out,Actually, both the actual naval engagement and its aftermath are hardly the makings of legend. The encounter was between the Arethusa and the French ship, La Belle Poule in June 1778. Though she was marginally a stronger ship, the Arethusa was, in fact, disabled, and La Belle Poule, whilst she sustained heavier casualties, sailed off. The Arethusa had to be towed back to the English fleet. This was not how the song had it … Prince Hoare obviously never quite let the facts get in the way of his story:

The English Channel to cruise about,

When four French sail, in show so stout

Bore down on the Arethusa.

The fam'd Belle Poole, straight ahead did lie,

The Arethusa seem'd to fly,

Not a sheet or a tack, or a brace did she slack;

Though the Frenchmen laughed and thought it stuff,

But they knew not the handful of men how tough

On board of the Arethusa.

On deck five hundred men did dance,

The stoutest they could find in France,

We with two hundred did advance,

On board of the Arethusa.

Our captain hailed the Frenchmen, ho;

The Frenchmen then cried out, hallo,

Bear down d'ye see to our Admiral's lee,

No, no says the Frenchmen, that can't be.

Then I must lug you along with me,

Says the saucy Arethusa.

The fight was off the Frenchman's land,A few months after the encounter the Arethusa was wrecked whilst once more engaged in chasing the enemy.

We drove them back up on their strand,

For we fought till not a stick would stand

Of the gallant Arethusa …

And now we've driven the foe ashore,

Never to fight with Britons more,

Let each fill a glass to his favourite lass,

A health to the Captain and officers true,

And all that belong to this jovial crew

On board of the Arethusa.

It was William Shield (1754-1829) who made the song in the form in which it became known. Shield was a County Durham man whose father was a singing teacher. After his father's death Shield became a boat builder although he also learned the violin and began to study music with Charles Avison (who was a noted composer and organist of the time) eventually becoming Master of the King's Music in 1817. His aspirations in music were vested in several fields including the production of glees, pantomimes, musical plays, church music, operas and string quartets as well as at least two books of musical theory. Haydn was counted as a friend.

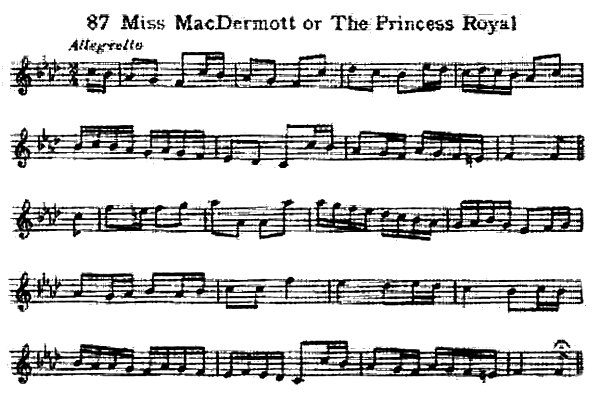

Amongst his many projects, Shield collaborated with the Dublin-born but thoroughly Anglicised John O'Keeffe on the opera The Poor Soldier (1783), from which a number of pieces were taken as fodder by various broadside ballad printers; and, like O'Keeffe, was known to have introduced traditional airs into his works. It was O'Keeffe who seems to have taken up the music of Turlough O'Carolan; but Shield, apparently, was the one who used O'Carolan's tune, Miss McDermott and welded it to the words of The Arethusa, though this may have been through the intermediary stage of Walsh's Complete Dancing Master, first published in 1730 where it carried the title of Princess Royal (see below).

The song, the Arethusa, eventually appeared as such in Shield's opera, The Lock and Key, in 1796. It was certainly à la mode. The fame of Charles Dibdin (1745-1814) was at its height. O'Keeffe himself was known for such songs, Tom Starboard among them; and, indeed, Shield set the words of John Rannie's The Post Captain, often found on broadsides. And broadside printers continued to pour out pieces such as Will Watch and Ben Backstay.

The Arethusa may not have been the first piece to have been put together with O'Carolan's tune. Eoghan Rua O'Suilleabhean is credited with the text of Rodney's Glory, about Admiral Rodney's defeat of La Grasse at the battle of Les Saintes, in the West Indies in 1782. O'Suilleabhean's history is itself an unusual one. He served in the English navy as did many Irishmen and it does not seem that he was convinced to do so by the sweet talk of the press-gang. We can guess, at the same time, that there was little enough for him at home. He was at Les Saintes and afterwards produced his poem. It has been suggested that the flattering tone was meant as a plea for release from his duties - which plea failed, as it happens. He did eventually escape the Navy but died in 1784.![]() 2 What is extraordinary is that O'Suillabhean was one of the more accomplished writers in Ireland who gave voice, in Irish, to an extended lament for the decline of his native culture which decline was accelerated to virtual destruction by English domination. In effect, he was one of the last of the Irish bardic poets. Rodney's Glory, in this history, is an unlikely product. For our purposes here it is enough to offer a sample from the text which reveals that the metre matches the tunes of the Arethusa and Miss McDermott exactly …

2 What is extraordinary is that O'Suillabhean was one of the more accomplished writers in Ireland who gave voice, in Irish, to an extended lament for the decline of his native culture which decline was accelerated to virtual destruction by English domination. In effect, he was one of the last of the Irish bardic poets. Rodney's Glory, in this history, is an unlikely product. For our purposes here it is enough to offer a sample from the text which reveals that the metre matches the tunes of the Arethusa and Miss McDermott exactly …

'Twas in the year of eighty-two,We know, too, that Miss McDermott was used as vehicle.

(All Frenchmen know full well its true),

Brave Rodney did their fleet subdue,

Not far from old Port Royal;

Full early be the morning light,

The proud De Grasse appeared in sight,

And thought brave Rodney to affright,

With colours spread at each mast head,

Long pendants too; both white and red,

As signals for engagement.3

The subsequent history of the song, The Arethusa, during the nineteenth century reveals more twists and turns. Nowhere, as indicated, does the song emerge in traditional sung repertoire as we know of it but in the continuing fashion for all things nautical Charles Incledon (1763-1826), the undoubted supremo amongst tenor singers of his day, sang it regularly along with Black-Ey'd Susan and Sally in our Alley; and the tune did resurface as a vehicle for the words of Bold Nelson's Praise and of Boney's Lamentation, each of which did emerge in traditional song repertoire, in the collections of Cecil Sharp and Lucy Broadwood. The nature of the metrical beast, as is shown above, is rather more complicated than the frequent four-line strophe of traditional song and, in this respect, other texts such as that of England's Glory or Bonaparte's Downfall, a piece relating to the battle of the Nile - strictly, Aboukir Bay - in 1798, could well have attracted the tune. All these pieces have similar metrical patterns as the following quotations, from Bold Nelson's Praise, Boney's Lamentation and England's Glory … respectively demonstrate:

A further comparison may be made. The Bonny Bunch of Roses and, then again, The Grand Conversation on Napoleon, both of which appear in numbers of versions later in traditional repertoire, were songs which exploited even more sophisticated stanzaic patterns and we also have the example of lollipop, the air and recitative, The Death of Nelson, a particular favourite of another well-known singer, John Braham (1777-1856).Bold Nelson's Praise

Bold Nelson's praise I'm going to sing,

Not forgetting our glorious King,

He always did good tidings bring,

For he was a bold commander.

There was Sydney Smith and Duncan too,

Lord Howe and all the glorious crew,

These were the men that were true blue,

Full of care,

Yet I swear,

None with Nelson could compare,

Not even Alexander.4

Boney's Lamentation

Attend, you sons of high renown,

To these few lines which I pen down,

I was born to wear a stately crown,

And to rule a wealthy nation.

I am the man that beat Beaulieu,

And Wurmser's will then did subdue,

The great Archduke I overthrew,

On every plain

My men were slain,

Grand treasures too I did obtain

And got capitulation.5

England's Glory

Come let us ponder for a while

Upon the victory of the Nile

And then you'll think it worth your while

To boast of Nelson's glory.

The gallant hero of the sea

That gained the last great victory

He was upon the raging sea

He did fight day and night

To maintain Old England's right

And all for Britons glory.6

In all this, at least a general period of relevance in this song context, to French wars at the latter end of the eighteenth and at the beginning of the nineteenth centuries, and then the nature of each song, including The Arethusa, as paeon, were firmly established.

However - and, in one way to recapitulate a different history - Walsh's version of the tune was almost certainly named for Her Serene Highness Princess Anne of Hanover, Duchess of Brunswick and Luneburg (1709-1759), born five years before the occasion when her paternal grandfather, the Elector Georg Ludwig, ascended the English throne as King George I. The title of Princess Royal was bestowed on Anne in 1727 by her father, George II - she was the second princess so entitled after Mary Stuart, daughter of Charles I.

Frank Kidson pointed out that:

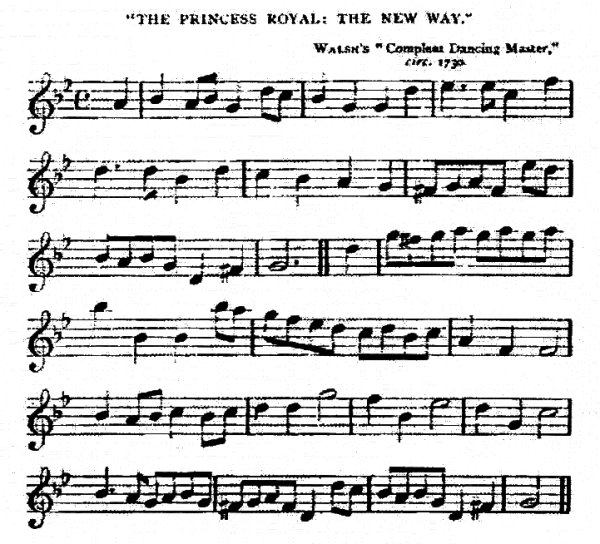

under the name Princess Royall the new way, the air, agreeing, almost note for note, with the Arethusa version, is found in an edition of Walsh's Compleat Country Dancing Master, c.1730, with a tune named Princess Caroline, on the preceding leaf … and under the title New Princess Royal in Wright's Compleat Collection of Celebrated Country Dances, vol. i. c.1730-35 … Wright's copy is reprinted from the same plates in a later edition, published by John Johnson. In Wright's dances is the air named Prince William. As The Princess Royal the air also appears in Daniel Wright's Compleat Tutor for Ye Flute, circa 1735 …Kidson was dismissive of any claim that the tune came from O'Carolan but this may have been to overlook the sources from which Walsh himself got the tune. O'Carolan, apparently, had composed a tune in honour of the eldest daughter of one of his regular patrons, the MacDermott Roe. It was supposedly in the house of his patron, under the eye of Mrs MacDermott Roe, a particular friend, that O'Carolan died … somewhere around 1738. There seem to be no written sources in England available before Walsh but the dates of O'Carolan's contribution and the assemblage by Walsh (et al) are sufficiently commensurate to allow time for the transmission of the tune.7

A dozen broadside printings, mostly from London, indicate a continuing popularity for the text![]() 9 and we also know that the tune itself was suggested, on broadside, for other texts - one, for example, for 'A New Song on the Jubilee … of his majesty King George the Third having entered the Fiftieth year of his reign' …

9 and we also know that the tune itself was suggested, on broadside, for other texts - one, for example, for 'A New Song on the Jubilee … of his majesty King George the Third having entered the Fiftieth year of his reign' …

Then, Britons, love your aged King,Another, issued by Jennings in London and entitled The Mill, took as subject a prize fight between Tom Cribb and a 'gallant fighting Black man' who is likely to have been Tom Molineaux, a one-time American slave. If this is so the fight took place in 1810 and was followed by a return match in 1811. Cribb won both, as it happens. Interestingly, the narrative movement of the piece appears to have anticipated the fight itself - which is not described - and looks to have been meant simply to stir interest, suggesting, for instance, that Cribb must be laid low. And the tune would have had to be adapted since the text lacks certain crucial forms of lines towards the ends of each stanza in the Arethusa.

And bid the merry bells to ring;

Awhile forget your cares, and sing

“Great George our King,” with spirit …10

A full stanza from the Cribb piece shows how the text was curtailed:

Now Cribb, a man of a black trade,The George piece, incidentally, follows the Arethusa pattern exactly.

Of black and white was ne'er afraid,

And hithertoo hath prov'd a blade

Worthy of high renown, Sir;

That his friends, we hear, look very glum,

And no few swells are nearly dumb,

For fear he should dislike the fun,

On the Eighteenth of December.11

There is still another aspect to note. The apparent date of genesis of the tune and its immediate pedigree have a particular bearing on any absorption into Morris dance tradition where it became well-used - a firm standby (as a jig) at, for instance, Bampton, Bledington and at Ilmington. It could well have been taken into repertoire before the end of the eighteenth century … the name, springing, it seems, directly from Walsh, might suggest this.

It really is quite an extraordinary story. At risk of overloading the piece with significance, we can yet see in the elements of its makeup signs of how a particular piece and, perhaps, others like it, moved around and between various social and imaginative milieux. In this case, the movement began beginning with the long-established though essentially declining mutuality of Big House patronage of music and song and poetry in Ireland and touched the very act of crushing the indigenous culture of Ireland. It reflected the taking up of things Irish and Scottish (and, as it happens, Welsh - a neglected subject) both as romance and, it may be felt, as a way in which to cement the growing sense of British identity during and, most especially, at the end of the eighteenth century - between, that is, the Act of Union with Scotland in 1707 and then with Ireland in 1801 and through a period of anxiety coincidental with riot and rebellion - 1715 and 1745 are major examples but with the addition of many food riots, riots for and against Catholic emancipation, election riots and so on to one of unification of sorts against a common enemy, France. It may be said to have been part of a widespread indulgence in popular musical and dramatic forms during the first part of the nineteenth century which began to escape the dominance of Italian form. There was a continuing commercial spin-off during the nineteenth century through the circulation of printed material especially as a facet of the school of Jolly Jack Tar-ism. Then, underlying and sometimes weaving in with this melange, there was a kind of parallel interest in the realms of traditional song as celebration of actual victories and actual heroes. Finally, the tune appeared as a feature of continuing and healthy Morris dance contexts.

Disclaiming possible smugness, one wonders how many Promenaders would be aware of this history.

Roly Brown - 30.3.05

Oradour sur Vayres, France

2 - See, for example, Terry Moylan: The Age of Revolution in the Irish Song Tradition (Dublin, The Lilliput Press in association with the Goilin Singers Club, 2000) pp.5-6.

3 - This is from Madden, Reel 91, Number 625. There is no imprint but the Reel number suggests, like others with the number 91, printing in Cork.

4 - See English Folk Songs Collected and Arranged by Cecil J Sharp, Vol.2 (London, Novello, 1912), pp.94-96. Sharp's manuscript version is in Folk Tunes as 238O, collected from Tom Gardiner in Blackwell, Warwickshire, September 9th 1909.

5 - See Lucy E Broadwood: English Traditional Songs and Carols (London, Boosey, 1908), pp.34-35.

6 - See the Madden collection, Reel 90, Number 363 … from Storer in Bristol.

7 - This extract is from the web which, unfortunately, did not provide a reference (nor have I been able to locate the article so far). Further, though, the substance was repeated in an article for Musical Times (October 1, 1894) which Baring-Gould used in notes on The Arethusa in English Minstrelsie, Vol.3 (Edinburgh, T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1895), Notes to Songs, p.vii.

8 - For details of O'Carolan's life, see Donal O'Sullivan: The Life Times and Music of an Irish Harper (London, Routledge, 1958), especially in Vol.2, p.52, where he discusses the dedication of the tune to Elizabeth McDermott Roe.

9 - Printings include those from Jennings in Madden, Reel 74, Number 334; Catnach in Madden, Reel 77, Number 693; Taylor (London) in Madden, Reel 80, Number 19; Fordyce in Madden, Reel 83, Number 367; Swindells in Madden, Reel 85, Number 155; and Keys (Devonport) in Madden, Reel 90, Number 35. The text as given in this piece is composite, taking into account differences in orthography; but the various texts used are commensurate.

10 - See Madden, Reel 74, Number 338, from Jennings.

11 - See Madden, Reel 74, Number 334, from Jennings.

Correspondence:

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 29.3.05