A collection of shorter pieces on subjects of

interest, outrage or enthusiasm ...

|

Enthusiasms No 80 A collection of shorter pieces on subjects of interest, outrage or enthusiasm ...

|

Following on from the discussion of how the various forms of My father's a hedger and ditcher came about (Enthusiasms 79) and, similarly, how Bonny Light Horseman acquired a Napoleonic tint (MT article 195), it seemed worthwhile giving another example of change of emphasis in text and context via The Ratcatcher's Daughter.

The piece in a rather unlikely instance is credited in some measure to the Reverend Edward Bradley (1827-1889) and was taken up by the nineteenth-century comedic singer, Sam Cowell (1820-1864). Sam Cowell is referred to in some sources as the virtual creator of music-hall as it existed in the 1840s in London especially - at venues such as Evans' Song and Supper Rooms where Cowell himself appeared regularly. The entrepreneur Charles Morton, having seen Cowell in action, took it upon himself in 1856 to re-create Evans' Supper Rooms in Lambeth, a comparatively rough and ready location; and he established the Canterbury Hall 'as a tavern music hall' and secured Cowell's services.![]() 2

2

Otherwise, The Ratcatcher's Daughter in contemporary or near-contemporary guise could have been located in several different places. Dickens, for instance, wrote of a time 'in a watering-place, out of the season', of a music shop window:

One commentator mentions the piece as having appeared in 1846.![]() 5 Another cites a correspondent to the Musical World in 1855 declaring that:

5 Another cites a correspondent to the Musical World in 1855 declaring that:

To step back a little, though, Edward Bradley had taken a degree at Durham university in 1848 and gained a licentiate; adopted the pseudonym Cuthbert Bede and was most noted for The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green, set in Oxford, and published in three parts between 1853 and 1857. Although the matter is not at all clear it seems probable that Bradley had simply added to or changed a pre-existent song or text and even if he did eventually do quite a bit of damage to the original script he can not be a candidate for its origin. Indeed, James Hepburn raised the matter in his book, Scattered Leaves. He cites Renton Nicholson in The Lord Chief Baron Nicholson (London 1860) as saying that the song (note the term) was popular in the 1820s and that he had heard it sung at Joy's Tavern in 1825. Hepburn does indicate that Nicholson is not necessarily the most reliable witness but doubt is obviously thrown onto the Bradley connection with the initial emergence of The Ratcatcher's Daughter especially since there is some supportive evidence for Nicholson's remarks.![]() 8

8

In fact, the supposed Bradley connection - in association with that of Cowell - was highlighted by a correspondent to Notes and Queries (admittedly at a quite late date) who referred to Cuthbert Bede's (Bradley's) 'assertion' that:

Perhaps, too, Bradley's assertion (as recorded above) is an admittance that he had nothing to do with composing The Ratcatcher's Daughter.

Cowell, though English-born, had spent his early life in America and did not return to England until 1840 so this 'fits' the comments given above; and as his memorandum indicates, he was much associated with the song during the 1850s (he was also noted for singing Villikins and his Dinah and Billy Barlow). Cowell returned to America in 1860, but suffered declining health which persisted on his return to England in 1862, forcing him to retire from the stage.![]() 10 Whatever the nature of Sam Cowell's considerable involvement, he was no more responsible for any original text than was Bradley.

10 Whatever the nature of Sam Cowell's considerable involvement, he was no more responsible for any original text than was Bradley.

***

But broadside history helps us to focus on how The Ratcatcher's Daughter developed from a relatively straightforward narrative into a performance-related piece as part of an entertainment characteristic of nineteenth century theatre (the Astley's syndrome as discussed in previous MT pieces), eventually coalescing as music-hall. Misfortunately, there is no corroborating sign of it as a performance piece in those newspapers available to this writer. This may well reflect its character as being unacceptable to the fashionable palate at the time; but commentators, as already seen, attest to its popularity in a wider social context.

There are then three small points to be made. It should be noted that the broadside title appeared as The Ratcatcher's Daughter, The Rat-catcher's daughter and Rat Catcher's Daughter. It should be borne in mind, too, that we are reliant on broadside copy that has emerged and that it may just be that there is more. There is also opportunity here to correct an earlier suggestion about the paucity of broadside copy, given in MT article 144 on Devon printers and including the name of Wilson of Bideford as being connected to the Ratcatcher's Daughter (see more below).

Following on: broadside copy of the ballad exists as printed by Catnach and the window of issue is worth noting: 1813-1838. The title appeared in Catnach's 1832 catalogue so a date for previous composition is nudged into view. The 1832 date was also only five years after the birth of Bradley which clinches the argument against the Reverend except when he may have added to or altered text. Further, Catnach issued copy along with his agents Bennett in Brighton and Thomas Batchelar in London. The latter was ensconced at 14 Hackney Road Crescent, his address as given on copy, in 1828. The window of opportunity for first known broadside issue of the piece may have narrowed a little to between the two dates 1828 and 1832 (although the Catnach and Batchelar union existed until Catnach ceased to print in 1838 - Batchelar continuing until 1842). This does not quite support the anecdotal evidence as cited above except for the Nicholson reference but a period in time for the emergence of the piece is pushed into view.![]() 11

11

As for the Catnach text itself, some characteristics stand out. Catnach issue of the ballad in question - as found in the Bodleian archive - was in one long column as if it was a slip song. Text was in standard English: what one might tentatively take to be the original broadside form. The narrative ended after seven stanzas with the death of an eager sand-seller and his romantic target, a ratcatcher's daughter.

Pitts printed this, after 1819; and so did Taylor in London. Both copies are in standard English and in seven-stanza form.![]() 12

12

William Jackson in Birmingham (1839-c.1853) printed the piece in the same form as did Catnach. Jackson is described on copy as 'late Russell' and the change-over date is clear, putting it at a point after the first Catnach printings and his catalogue reference. However, there is no sign of the ballad in Russell's output as listed by Roy Palmer in MT article 238. Jackson may, then, have taken his cue from Catnach - or from a source unknown.![]() 13

13

Margaret Hodges, inheriting from Pitts, printed one version in standard English and ending after seven stanzas (in the Bodleian archive) and also two other copies in more familiar broadside style, alongside PADDY'S WEDDING (in Madden). Text is the same in all three - 'From the late I (sic) PITT's'- but one copy was printed from 31 Dudley Street and the other two from the Toy Warehouse; and one of the latter has the information that Margaret Hodges 'has Removed from Dudley Street...'. In this small complex, whatever else, this indicates a succession of issues. The Bodleian, in fact, places its copy within the time-scale 1846-1854. Whatever else again, this coincides with the period when the piece first appeared and then had its heyday.![]() 14

14

Bebbington in Manchester (the Bodleian gives ballad-printing dates of 1855-1861) printed copy that was also sold by a John Beaumont, distributor of ballads who, according to copy, was working out of 176 York Street, Leeds. At the time of issue of the ballad, Bebbington was working from Goulder Street, his address on copy. Between 1858 and 1861 he had moved to Oldham Street. The Bodleian, accordingly, dates copy of the ballad from between 1855 and 1858.

Importantly, Bebbington's Ratcatcher… has seven stanzas in conventional English.![]() 15

15

Other named copy, as noted below and in a changed form, came from Wilson in Bideford and from Harkness who, as will be seen, may well have acted as a catalyst for the progress of the piece.

Steve Roud does list the song (via a Baring-Gould collection) as having been issued under the auspices of Samuel and John Keys in a songster entitled The Merry Warbler; but Samuel and John did not take over their father's business until c. 1870. The father, Elias Keys, had not issued the piece during his own ballad-printing career, effectively between 1830 and 1840. At the same time, through the involvement of the two sons, the life of the piece can be seen to have been prolonged and its appearance at this comparatively late date could well have been a factor in further progress by virtue of dissemination by one means or another - which there certainly was.![]() 16

16

Finally, Steve Roud lists a copy from Dublin which would have been at a relatively late time since Irish ballads, on the whole, emerged after their English counterparts.![]() 17

17

All told, working within and around a time suggested by the dates of these printers shows that whilst genesis was at a relatively early time, even if a first date is still unclear, the bulk of exposure threaded through the middle and second half of the nineteenth century.

***

To come to the nub of textual development - the beginning of the piece in standard broadside form is as follows:

In rapid order they agreed to be married but then she, unfortunately, drowned, whereupon he:

In respect of development, there is an adoption of a kind of slang: the use of a 'w' instead of a 'v', for instance (see, as an example, Werry Pekooliar);![]() 19 and the presence of the 'h' in the 'wrong' place or its omission altogether, also both characteristic of the trend. Derek Scott has a deal to say about how this may have been intended to represent 'Cockney' speech, known sometimes as 'Mockney'.

19 and the presence of the 'h' in the 'wrong' place or its omission altogether, also both characteristic of the trend. Derek Scott has a deal to say about how this may have been intended to represent 'Cockney' speech, known sometimes as 'Mockney'.![]() 20 Sam Weller comes to mind as a character who used this form of English in Pickwick Papers, which came out in 1837. Magwich, in Great Expectations, asks Pip 'Do you know what wittles is?' though not until 1860-1861 when this novel was first issued. It may be that there was a prolonged flirting with 'Mockney' in literature - and the music-hall. Dickens certainly set Great Expectations back in time during the early and middle part of the nineteenth century (for fictional purposes much as Hardy set novels back in time).

20 Sam Weller comes to mind as a character who used this form of English in Pickwick Papers, which came out in 1837. Magwich, in Great Expectations, asks Pip 'Do you know what wittles is?' though not until 1860-1861 when this novel was first issued. It may be that there was a prolonged flirting with 'Mockney' in literature - and the music-hall. Dickens certainly set Great Expectations back in time during the early and middle part of the nineteenth century (for fictional purposes much as Hardy set novels back in time).

At any rate, the beginning of ballad copy, in this mode, is as follows:

In five broadside copies without imprint but with the legend 'Song 252' on them there is an extension of narrative and, moreover, the mode in these copies is that of 'Mockney' as opposed to conventional English. There is also a recommended chorus - the same on all copy - after the first stanza a full line, 'Doodle dee, doodle dum, ri, da, doo, da, di do' and after subsequent stanzas, merely 'Doodle dee, &c'. One of the five ballads is in the form of a column (as in Catnach). All the others spread across copy in two columns. At least a glimpse of succession is found. The printer, though, has not yet been identified… ![]() 22

22

In another copy, without imprint, there is a chorus line after the first stanza rendered as 'Doodle dee, doodle dum, di dum doodle...(?) - this, whilst not 'complete' (a final word may have been 'dee' but is obscured on the particular copy) clearly has echoes elsewhere; but there is no repeat of the full chorus line nor even a shortened chorus after any other stanza. Moreover, whilst the piece has seven stanzas yet it also has the change into 'Mockney' which, as already noted, does not seem to have been a first idea in text. In addition, the header block is set sideways above the text. This copy seems to be an odd man out.![]() 23

23

In other copy there is another development involving the addition of two more stanzas. Where the narrative is extended, the neighbours

Finally, there are copies with spoken sections, the first of these after the sixth stanza:

The textual developments in The Ratcatcher's Daughter give an exaggerated - even gratuitous - character to the piece compared with that in any first issue under named printers and it does seem that this is indicative of a context beyond the bounds of printed balladry where entertainment, sometimes riotous, was a moving force. For present purposes it is enough to note that the chorus lines, in particular, would suggest a degree of regular performance and, adumbrated though they sometimes are, such lines must have relied on the assumption that any audience would be able to supply a full familiar chorus. The spoken element, too, must surely betoken performance of one kind or another.

***

In all this, it is worth looking at the Harkness contribution more closely. There are four Harkness copies in the Bodleian archive. Two of these are numbered '805'. Harkness was apparently meticulous in numbering his extensive copy and The Ratcatcher's Daughter appears at about the halfway point in his output. Since Harkness began his ballad-printing somewhere around the 1840 mark - perhaps a little before - and finished at around 1866, a potential date for the appearance of the ballad under his aegis can be abstracted. In fact, Gregg Butler points out that the number on Harkness copy before '805' is dated to an event on 19th February 1857 and that the number '887' appears on other copy dated to an event on 14th January 1861.

Both '805' copies are in conventional English. Both have seven stanzas. Both indicate chorus lines that repeat the final line of each stanza. This might well suggest that they were issued at a relatively early date - the ballad being still in the process of alteration - and likely to have coincided with Cowell's intervention.

But it is not the case that, as so often in the Bodleian archive, one is simply 'another copy'. Both copies do sit alongside a piece entitled Bonny Nelly Brown. However, the header blocks on each are slightly different, showing gentle maidens but one, it would appear, in older dress. The other copy has a girl with a hoop and there is an additional reference on that copy - to 'Sec. 24'. Gregg Butler hazards that this may be because Harkness distributed copy to printers elsewhere (and cites, particularly, Stewart of Carlisle and other relatively local distributors as well as London printers as recipients) and, so as to distinguish these copies, added the 'Sec' number.![]() 27

27

There is one more Ratcatcher… text, credited to Harkess, and with the number '805' on it. Much of the text is blacked out but there is enough to indicate that there are seven stanzas, that the final words of each stanza are repeated as a chorus and that text is in conventional English.

In fact, there are two examples of the piece on this particular sheet and the sheet appears again in the Bodleian archive as one without imprint. The second text on the sheet (not, then, the Harkness copy) employs 'Mockney'… but there is no suggestion of a chorus.![]() 28

28

Another Harkness copy (the text sits alongside a ballad entitled Blind Boy) has the number '823' on it. The piece seems to be another one to indicate that the ballad was still in the making for, radically, it has the two extra Sloman stanzas that also appear on those copies with the designation 'Song 252' on them (copies without imprint as discussed above). There is a full 'Doodle...' line after the first stanza and thereafter just a 'Doodle, &c'; and Harkness here favours the use of 'Mockney'.![]() 29

29

Interestingly in terms of a printer's profile, there is no address on any Harkness copy and, together with his presentation of the different forms of the ballad, this would ultimately suggest a printer wholly confident of his place, at least within his geographical hinterland. The distribution of copy elsewhere than the Preston hinterland indicates a degree of his expansion and influence: another mark of confidence - but, ultimately, another story.

To bring the Harkness saga to a head: since he worked within and around the time period of most of the named printers noted above bar Catnach and since he put out both the 'conventional' version and the one that extends it, he is clearly important in terms of the new direction of printed copy before - even as - it was taken up as a sung piece.

***

Apart from Harkness, Wilson in Bideford whose ballad-printing dates are c. 1830-c.1857 had the two extra Sloman stanzas, which allows us another glimpse not only of a textual advance that underlines a chronological order of printers but of a probable association with performance.![]() 30

30

***

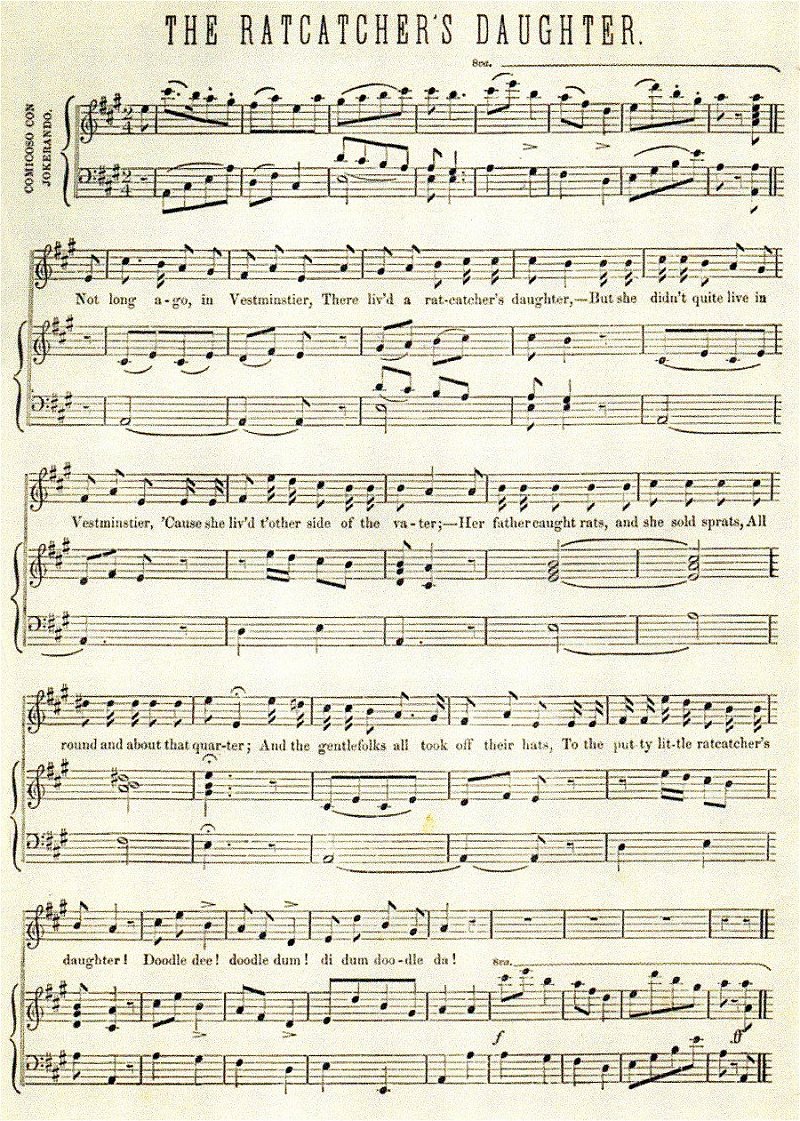

Taking into account the growth of the piece as it incorporated Sloman's contribution, it would be expected that this is the version that came to have a prominent life in performance; and this is confirmed in least one Sam Cowell version - online (and below) - that contains the Sloman input. The version provides text and tune together inclusive of the two Sloman stanzas and a chorus line beginning with 'Doodle...' that is replicated elsewhere with one or two slight changes depending on context. There is no evidence, though, that Cowell incorporated sections of speech.

The song has a profile that can then be traced to an extent through the latter half of the nineteenth century. There were several printings, some in America, featuring the cover as noted here above and some derivations. A copy from Boston - the most prominent - is listed as having been created via lithography by a J H Bufford and printed by Oliver Ditson but this cannot, so far, be dated accurately. On the other hand, an online London Museum reference to the song edition is to the years 1844-1846. Almost inevitably, too, there were developments such as a set of variations on the air from a W Wilson, published by Davidson in London at around 1855, such attention being a feature of composition as was seen in connection with Crazy Jane (MT article 308); another version 'Arranged With Harmonised Chorus for the Pianoforte' from a W J Allen, also in 1855; and a third example of a version arranged by an E J Westrup, first published in the same year ...

There was also a steady accumulation of printings in songsters. Marshall in Newcastle would seem to have been one of the earliest printers in this form in his New Theatrical Songster - Marshall's dates are given as 1810-1828. There seems then to have been a kind of jump over years until the version from The Poet's Box in Glasgow that dates from 1858. This is followed by Beadle and Co.'s Dime Song Book No. 5 (1860) in New York; in the Great Comic Volume of Songs - with music (c. 1863); in The Comic Songster (1870); in Comic Songs Sung by Sam Cowell - with music (c.1878); in Cole's Funniest Song Book in the World (1890). One might also mention another American version, published by S T Gordon on Broadway in 1900 (online - my italics), further prolonging the life of the song.

Ashton's Modern Street Ballads also contained copy (1888).![]() 31

31

It can thus be assumed that song versions, found in the music-hall and in a widening published guise, were principal agents in encouraging further popularity.

***

Then, too, if the Keys post-1870 textual input is taken as a measure of continuing interest, the ballad can be seen to have infiltrated comparatively modern times. That this was so is proved by the re-surfacing of the piece in notations made by Vaughan Williams and George Butterworth during a visit to Norfolk in 1911. During their short visit (19th-21st December) to the Diss and Tibenham areas the two came across half a dozen singers, one of whom was William Tufts senior, born in 1828 and so providing a long, notional learning period that includes the continuing issue and performance of The Ratcatcher's Daughter. The surname was well-known, sometimes as 'Tuffs - which is how Vaughan Williams put it on manuscript copy.

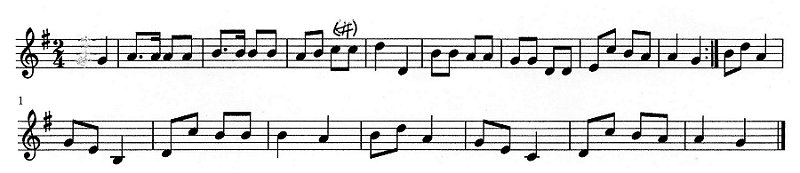

Several songs were noted by both collectors and the tune of The Ratcatcher's Daughter exists in manuscript form from each of the collectors. In other manuscript versions of songs made during this trip Vaughan Williams and Butterworth sometimes differed in their time signatures where one collector might indicate that, say, four-four was appropriate and the other two-four. In the case of the Ratcatcher..., although the time-signature is not given by either collector, the notation makes clear the vigour of a two-four timing. Vaughan Williams, in a manner that he had adopted in collecting matters, wrote 'doubtful' on his manuscript where he felt that he had not heard the piece accurately. However, setting the two versions together reveals that music-notes themselves more or less correspond, certainly enough to provide an outline of how Mr. Tufts sang the song.![]() 32

32

No words were taken down but comparisons may be made with the tune Mr Tufts used and that from Sam Cowell.

The tune from Mr Tufts, as found in the Vaughan Williams and Butterworth manuscripts, offers an eight-bar phrase that is then repeated.

This accommodates the first half of any eight-line section of the song and the repeat of the phrases would take in the full stanza; but there is a caveat. The notation is not the same as that from Sam Cowell. In fact, Mr Tufts only sang the second half of Sam Cowell's tune - without benefit of a sharp note at the point indicated in notation given above.

There can be no doubt about the correspondence of the chorus lines. In the Tufts version, as shown, the second eight-bar sequence fits a chorus line that would contain the Doodle... jingle that is very much the same as that from Cowell except for the final notes. These, it has to be presumed, matched other syllables, most likely to have been '(di) - DO' in line with each of the broadside copies without imprint - '252' - that carry the chorus-line as 'Doodle dee, doodle dum, ri, dee, do, da, di do'. This might, in turn, suggest that Cowell's was not the sole sung version in circulation (variant text has already been noted) - but, mostly, one returns to Cowell as a principal agent.

It might be surmised, as a result, that, after all the textual developments and music-hall exposure, Mr Tufts had encountered the ballad - the song - directly at a performance or, again, by oral dissemination: hardly a startling conclusion. But the chances are that the song was still being sung inside or outside music-hall when printed single ballad copy was fast disappearing. In sum, however it was arrived at and whatever its subsequent progress, it looks as if Mr Tufts gave Vaughan Williams a stage version, of Ratcatcher's Daughter but that it is not quite the version perpetuated by Sam Cowell. It nonetheless offers a glimpse of under-currents and certainly promoted the continuing life of the ballad into the twentieth century.

***

To confirm a further legacy, one draws attention to the version got by Gwilym Davies from Charles Menteith in Cheltenham in 1994. This version involves an intriguing degree of to-ing and fro-ing in both text and tune and in the manner of acquisition. Mr Menteith got the song in the 1960s and he believes that it was - probably - from a friend, David Grove (the latter from Edmonton). He is also perfectly aware that, as time has gone on, he has probably changed parts of the tune. It is also interesting that the possibilities of 'Mockney' character are slightly more erratic than in previous versions - of the text - in the two final (Sloman) stanzas… The piece from Mr Menteith had begun with the conventional 'Westminster' and much of the first part is straightforward. Then, at the point in narrative when the daughter 'vent vunce more' to buy sprats in Sloman versions, the words are regularised in Mr. Menteith's version. The word 'covered' (in mud) replaces 'kiver'd' as found in other copy. On the other hand, the word 'consta-iant' in the Menteith version does not appear in this exact spelling in previous versions although 'constaint' can be found in some. The phrase 'Rivier' Thames appears to be unique in Mr Menteith's version. None of this, though, compromises the piece in relation to any historical printings. ![]() 33

33

Mr Menteith also refers to a tune that certainly has echoes of the Ratcatcher's Daughter - may even have derived from it - from the fiddler Thomas Hampton (baptised 1844, died 1896). His probable source was T Westrop's 120 Country Dance Tunes (though dating of the latter is difficult).![]() 34 This at least gives us a coincidence of evidence for the last part of the nineteenth century.

34 This at least gives us a coincidence of evidence for the last part of the nineteenth century.

***

There are no claims here of a full, constant exposure of the piece down through the years. The more important process, if not quite in the mode of either My father's a hedger and ditcher or Bonny Light Horseman, is that of the change of character in the ballad and context for its lifetime.

Roly Brown - 14.6.17

Oradour sur Vayres, France

2. The Canterbury Hall was opened in 1852 and remodelled in 1856.

3. No doubt this information can be got elsewhere but, in this instance, was found online in Deep Roots magazine, 2012. So far, no date has been found for 'Out of the Season'.

4. See online a Dictionary of Victorian London for several references to the Grecian Rooms, formerly the Eagle Tavern.

5. See Arthur Hayward: The Dickens Encyclopaedia, Vol. 8 (unpaginated - the reference to 1846 can be found under 'R' in a Routledge Library Edition, 2010. The book was first published in 1924).

6. See Derek Scott: Songs of the Metropolis, OUP 2008, p. 174.

7. Images of the cover are easily available online. The online poster advertised performances at the Pavilion Theatre.

8. James Hepburn's observations can be found in notes to the introduction in his book (p. 273) that appeared in 2000.

9. See online Notes and Queries, July-December 1876.

10. Villikins... was a burlesque version of William and Dinah, couched in 'urban slang' - 'Mockney' - and much elaborated by Sam Cowell. The song seems to have emerged at around 1853. Billy Barlow is a version of Hunting the Wren, not in 'Mockney' vein; and there is a multitude of similar narratives especially in America.

11. Roud Catnach copy is found in the Bodleian archive as Harding B 17(251b) and and copy issued with Bennet and Batchelar as Johnson Ballads 227 and 228 and Harding B 11(2328) - they look like successive issues.

12. For Pitts, see Madden Volume 76, Number 538 and for Taylor, Madden Volume 80, Number 1 (it is not clear which Taylor but Henry appears to have issued most ballads under the name - at a relatively late date in the 1840s and after).

13. Jackson (and son) copy is found in the Bodleian archive as Harding B 11(502).

14. Hodges copy (from Pitts) is found in the Bodleian archive as Firth c. 18(230); and as Madden Volume 78, Numbers 325 and 326. The word 'familiar' is used to denote copy from slip or alongside another ballad

15. Copy from Bebbington and Beaumont is found in the Bodleian archive as Harding B 11(2232). The only other detail of Beaumont's career is that in 1826, according to BBTI, he was printing out of '5, North Low, South market' Leeds, most probably only generally. Bebbington also used other distributors. Beaumont worked with T. Pearson after 1861, from the same Oldham Road address previously occupied by Bebbington.

16. All Elias Keys ballads were issued from James Street, Devonport.. The Merry Warbler was printed from the same address though the two sons also printed from Aubyn Street. See Ian Maxted: Exeter Working Papers in British Book Trade Industry; 7 The Devon Book Trades: a biographical dictionary...Devonport (revised, August 2015)

17. The Dublin copy has no printer's name. John Moulden's thesis, The Printed Ballad in Ireland (Univ. of Galway 2006), covering the years 1760-1920, makes clear the generally late appearance of broadside ballads in Ireland.

18. As summary, standard copies include Catnach et al; Hodges 'late I. Pitts' (sic) found in the Bodleian archive as Firth c. 18(230); Bodleian copy without imprint on Harding B 19(29) and 2806; Jackson, Bebbington; and in a compendium (without a printer's name) found in the Bodleian archive as Firth b. 27 (457-458)

19. Werry Pekooliar can be found in Pitts' 1836 list; in Collard's 1837 list (but not in his Madden collection); and in Beadle's Dime Book, No. 10 (1863). A sort of companion piece, Werry Mysterious, can be found in the London Vocalist (c. 1840).

20. Derek Scott: op cit, p. 174.

21. See n.i. 2806 c. 15(24) in the Bodleian archive.

22. The four copies that have the same standard format are found in the Bodleian archives as 2806 d. 31(83), Firth b. 34(253), Harding B 11 (3233) and Johnson Ballads 3320. Copy in one column is found, same source, as Harding B 11 (2526). Apropos the name of the printer, readers are, of course, invited to submit suggestions.

23. Copy is found in the Bodleian archive as 2806 b. 9(246).

24. Charles Slowman, 1808-1870. The Literary Gazette… (1844), online, describes him as 'the clever extemporaneous singer' who was 'adding to his reputation by improvising a medley nightly at the Victoria'. A playbill for 1855 housed in the East London Theatre Archives cites Slowman as 'improvisatoire'. Other references have him composing songs for fellow artistes and for the audience.

25. All 'Sec 24' copies include these spoken passages.

26. There are three different forms of The Margate Hoy, one of which is from Dibdin and replicated, as example, in Oxlade copy as Madden Volume 89, Number 240..

27. These copies are found in the Bodleian archive as Harding B 11 (415) and Harding B 11 (416), the latter with 'Sec 24' on it. There is one slight query. Gregg Butler kindly sent a copy of a Harkness copy '804' - 'on the Dreadful COLLIERY EXPLOSION' but it, too, has the number 'Sec. 24' on it. Are we, then, talking about a number that signifies a batch of ballads?

28. Copy is found in the Bodleian archive as 2806 c. 13(120).

29. Copy is found in the Bodleian archive as Harding B 11(3234).

30. For Wilson see MT article 144. He can be seen as a printer with and extensive history and an equally extensive stock including currently popular ballads, mainly light in character; and a substantial number of semi-religious pieces.

31. Profile can be gleaned from online sources. All the songsters are recorded in Steve Roud's index and show, for one thing, how popular Cowell's songs became in America. A late bloom in printed form can be found in Johannsen's The House of Beadle and Adams 3, 1962, a re-issue of text.

32. William Tufts died on 6th February 1912.

33. Mr. Menteith previously used his version in his own way in the online magazine Folklife Quarterly.

34. Notes on Thomas Hampson can be found online in Gloucester Traditions (GlosTrad). One copy from Westrop, in the ITMA archives (Ireland), was issued minus a date. On a slightly negative note, the tune is also a reminder of The Curly-Headed Ploughboy. Westrop actually printed the Ploughboy immediately after the Ratcatcher…

Correspondence:

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 20.5.17