|

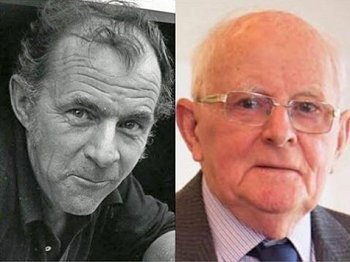

Jim Coughlan: 03.9.33 - 13.1.17

|

Jim Coughlan, who died on 13 January last in his eighty-fourth year, was one of a select number of singers and musicians associated with Swindon Folksingers' Club who stood out from the run of folk revival performers. (Others were music hall maestro Lucky Luckhurst, blues duo Fred and Nancy Foote, and fiddler Pat Casey, a first cousin of the legendary Bobby Casey.) Jim was a native of County Limerick, and was known in later years for the singing partnership he formed with his good friend Sean Burke, a Corkman with a fund of rousing songs and a great man for the craic. Jim was popular with all who knew him at Swindon, and was welcomed at those clubs and festivals which value old-style traditional singing.

Jim Coughlan, who died on 13 January last in his eighty-fourth year, was one of a select number of singers and musicians associated with Swindon Folksingers' Club who stood out from the run of folk revival performers. (Others were music hall maestro Lucky Luckhurst, blues duo Fred and Nancy Foote, and fiddler Pat Casey, a first cousin of the legendary Bobby Casey.) Jim was a native of County Limerick, and was known in later years for the singing partnership he formed with his good friend Sean Burke, a Corkman with a fund of rousing songs and a great man for the craic. Jim was popular with all who knew him at Swindon, and was welcomed at those clubs and festivals which value old-style traditional singing.

Jim put down family roots in Swindon from the late 1950s with his first wife Jenny, who sadly died many years back, and their children Geraldine, Sandra and young Jim; and with his second wife Gill and their daughter Laura. At the time of his death, Jim had seven surviving grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

In the autumn of 2002, long-standing SFSC member Luke Mitchell used his high quality recording equipment to document Jim's singing. The resultant non-commercial CD entitled Songs of a Limerick Man features twenty-four songs, giving a good idea of the range of material Jim knew, from his favourite Spancil Hill to a comic take on Galway Bay. What follows is essentially the introduction to the booklet which was put together to accompany the CD at the time.

One of a family of seven, Jim was born in 1933 at Clarina, a village adjoining the larger settlement of Patrickswell, in the district to the south of Limerick City. Coughlans' was a strict Catholic household, in which for example anyone fluffing the rosary during November, the month of Our Lady, could expect a ticking off. The family had strong roots in a community where everyone knew everyone else's business, news travelled fast, and the petty crime that plagues our more impersonal times was all but unknown. In those far off days, a rural settlement in the West of Ireland enjoyed few of the conveniences we now take for granted. In the absence of running water, all supplies had to be fetched from the well, including water needed at school - though this at least had the advantage of affording a break from the grind of the classroom. Electricity did not made its appearance in the village until the early 1940s. The first wireless, a primitive device by modern standards, was a great event, bringing with it an exciting glimpse of the outside world. Transport was rudimentary:?it was some time before Jim acquired a bicycle, and from there he eventually graduated to a moped, marking the beginning of his interest in restoring vintage motorbikes.

If life was in many ways hard, people also knew how to enjoy themselves. Music, of course, played a central part, but there was also sport, particularly in the form of hurling. Like most youngsters, Jim was fond of getting up to mischief. This got him into his fair share of scrapes, which he could later look back on with a smile. The local lads had a stock of larks they would play on neighbours, such as swapping over gates or placing a vessel of water so that it would be knocked over when the door was opened. Another ruse when entrusted with milk from the domestic goats (they were a family raised on the stuff) was to flog some of the liquid on the side - until the measure was discovered to be short. And not a few escapades arose in the course of employment.

Never much struck with school, Jim entered the world of work at thirteen, tackling a variety of jobs to bring in a few bob. His first position, seeing to chickens, involved a walk of four miles each way. After that, Jim secured a job on the estate of Lord Adare. Since this added two miles to the journey, he came up with the scheme of secretly borrowing his grandmother's donkey, which he rode bareback. This enterprising means of commuting lasted, unfortunately, no more than a few weeks before the old lady rumbled the ploy. A further common means of income was driving cattle overnight to market in Limerick, working from midnight through till noon, though Jim was unimpressed by the pittance paid.

These forms of employment were secondary, however, to Coughlans' long-standing link with the river Shannon as commercial fishermen. The family had a licence, handed down through the generations, to trawl for salmon from their boat. Jim's personal recollection of this stretched back to his grandfather, who belonged to a time when certain superstitions were still strongly attached to the enterprise: whilst making their way down to the boat all kitted up for a night's work, fishermen would go to great lengths to avoid passing a female in the lane, an encounter that was believed to bring bad luck.

While still a minor, Jim would join his uncle and father, who inherited the boat and coveted licence, to work on the tidal water at night, the catch being traded through a fishmonger in Limerick who supplied the hotel trade. This was a hazardous occupation requiring skill and courage. Nets would be set, and the catch stunned using a 'priest', a stick something like a truncheon. Alarmingly, salmon were not the only creatures of the river to find their way into the waiting nets. Jim recalled in particular a number of unpleasant encounters with otters. Once, he was nearly dragged overboard by one of these furry amphibians; another time, while standing over his knees in mud to secure one end of a net, an otter became entangled and he was lucky to escape without being bitten. This common hazard had given rise to an ingenious precaution: knowing that an otter will not release its grip until it hears a bone break, fishermen would put cinders inside their trousers to simulate the cracking of bones, an instance of the kind of popular wisdom of the river that had built up over the generations. From time to time there might be a yet more gruesome task to be performed, such as the night when the bodies of three men who had gone out shooting had to be retrieved after their boat had come to grief.

On at least one occasion, however, Jim brought trouble down upon himself. Activity on the Shannon was strictly regulated, which meant that fishing was off limits between Friday evening and Monday morning. In league with his uncle, a poaching plot was hatched that was almost the stuff of folk song. The river bailiff would be lured away by setting up a rendezvous with an attractive female relative, leaving the coast clear for some illicit weekend fishing; but she, not being party to the plan, failed to show up - leaving the bailiff free to intercept the hapless poachers. Jim, being under age, had to be represented in court by his father. The escapade carried a £7 fine and earned him a severe ticking off from Coughlan senior.

Other forms of casual poaching posed fewer dangers of punishment. Rabbiting was a habitual pastime, for which discarded fishing nets were employed in conjunction with dogs and ferrets to hunt down the quarry. The rabbits could then be sold on live to meet the demand for coursing, or used to supplement the family diet, a practice which proved particularly welcome during the lean war years.

These recollections of life and work in the West of Ireland in the 1930s and 40s extend the picture beyond the stereotype of subsistence farming to a wider spectrum of economic enterprise. In addition to his activities as fisherman, for example, Jim's father was the first in the district to own a motor lorry, used amongst other things for hauling felled trees. In a world where money was never exactly plentiful, country people managed to keep body and soul together by being resourceful enough to turn their hand to a range of tasks.

In 1956 Jim followed the path of countless compatriots. Emigration, while not forced upon the younger generation, was viewed by the old people of the village as a route to improved prospects in life. Encouragement extended to help with the fare; and the network created by successive waves of emigration meant there was always a relative or neighbour established abroad who would take you in. Deciding against joining an uncle in Canada, Jim made the customary journey to England, staying for a while with a relative in Balham, south London. Not much struck with the conditions on offer, he briefly returned home before giving England another go, this time in Birmingham, where he landed a job working on the telephone network for what was then the GPO. The job took him to many parts, and by the late 1950s Jim found himself in north Wiltshire. The work ran out at Chippenham, but he had in the meantime taken a shine to Swindon - a much more compact town in those days - where he considered the natives to be friendly, and so settled there, making a living mainly in the building trade.

At Christmas time, the family would often play host to an annual event known as 'The Gamble'. The main attraction was an all-night card school for a big prize such as a turkey, while a musical party took place in the next room, though generally little drink was consumed. The door would be taken down and set dancing would get under way: in the narrow confines of the cottage you had to keep your wits about you - round the house and mind the dresser! The dancing was accompanied by a noted local fiddle player who travelled round on a bicycle and led the music for a fee, joined by other musicians. Jim recalled hearing melodeons and concertinas, but that the fiddle was the principal instrument.

Christmas was also the time to do the rounds as Wren Boys. Disguised with a mask known as an 'eye fiddle', Jim and his mates would tour the neighbourhood - being careful to avoid other groups, such as the pipe band from Adare, engaged in the same activity - and sing for a few pennies or food and drink.

Music was also a feature of the pleasure fairs held round about, including singing competitions. Furthermore, music-making would often be grafted onto occasions in the working year, such as the feast to mark the end of the harvest (Jim remembered the time when this operation still involved steam threshing). These special occasions were in addition to the regular Sunday night gatherings held in the little hall at the adjoining village of Patrickswell: Jim would cycle over as part of a gang of lads from Clarina for an evening of music and dance, with entry at 6d (2.5p) and 1/- (5p).

As late as the mid-1940s, Jim distinctly recalled ballad singers operating on the streets of Limerick City, flogging song sheets at a penny a time. Although there were some of these sheets in the house, they do not appear to have played any significant part in the traditional process. There was also a wind-up gramophone, though the family was not able to afford much in the way of records, and this, too, had little impact on the singing tradition. So the performing and handing on of music remained predominantly oral. Although great importance was attached to learning Irish at school, English remained the first language for everyday purposes, and Jim could remember no singing being carried on in Gaelic.

Growing up where music was such a routine feature of life, it is easy to see how Jim acquired his love of song and how he came to absorb his authentic manner of singing. His musical apprenticeship confirms the view of the family as the cradle of tradition, bolstered by the many opportunities for music-making in the wider community.

Like all traditional singers, Jim would sing whatever took his fancy: some of his material he took in after settling in this country, but he instinctively absorbed it all into the singing style he learnt from his family in Ireland. He had a taste for the heart-tugging songs of emigration which have an obvious resonance, and for poignant love songs, but his sense of fun also gave him a feel for comic songs and parodies on classics such as Galway Bay. It was chancing upon Swindon Folksingers' Club in the early 1970s that brought him back into musical circulation after a dormant period. He became a regular at the club, giving members the opportunity to savour traditional singing formed in conditions quite different to the folk revival.

Andrew Bathe - 19.3.17