1925 - 2018

|

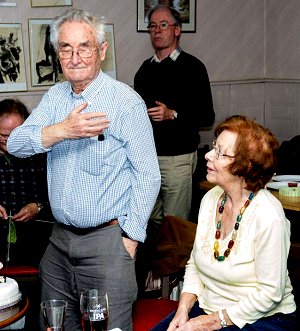

Ted Poole 1925 - 2018 |

Edward John Frederick Poole, known to all and sundry as Ted, was born in Kentish Town in north London in May 1925. His father, a sailor in the Merchant Navy, died in middle years, after which Ted removed with his mother to the Swindon area, where she remarried. By the start of the war, the family was established in Gorse Hill, north Swindon, near to where Ted ever after lived, apart from service in the RAF as an aircraft fitter during 1943-7. He married Ivy Barr, a fellow refugee from the Great Wen, in the summer of 1952 - they were to be inseparable for the best part of 66 years.

Edward John Frederick Poole, known to all and sundry as Ted, was born in Kentish Town in north London in May 1925. His father, a sailor in the Merchant Navy, died in middle years, after which Ted removed with his mother to the Swindon area, where she remarried. By the start of the war, the family was established in Gorse Hill, north Swindon, near to where Ted ever after lived, apart from service in the RAF as an aircraft fitter during 1943-7. He married Ivy Barr, a fellow refugee from the Great Wen, in the summer of 1952 - they were to be inseparable for the best part of 66 years.

If a single term epitomises Ted's life and endeavours it is activist, his own favoured self-description, which he pursued in two forms: politics and a strain of vernacular music-making which he only reluctantly termed 'folk'. Supremely a man of the people, he espoused early the cause of radical socialism, and campaigned throughout his life with unshakeable conviction for the interests of those with little significant voice in the political and economic scheme of things. Alongside this commitment to political action, Ted promoted, from around 1960, informal gatherings designed to encourage ordinary people to make music together, which eventually crystallised into Swindon Folksingers Club, still active today.

In purely personal terms, it seemed obvious to Ted that there was an intimate connection between these two worlds of left-wing politics and uncommercialised participant music, a late instance of which occurred in September 2011, when he helped organise an event under the historic battle cry ¡No Pasarán! This was a tribute to Percy Williams, a young Swindonian who perished in Spain in 1938 while making a stand against Fascism. Following the rededication of Williams's grave, a musical evening was led by singer and melodeon player Jim Bainbridge, a long-standing friend of Ted and Ivy.

Given these deep-set beliefs, it was to his credit that Ted never sought to make the Swindon Club overtly political. Instead, through the long haul of Friday gatherings in the clubroom, he provided several generations with the chance to sample the broad church of folk revival, leaving individuals to take from it what appealed to them. Weekly fare was subject to the shifting acts of the folk circuit, but Ted always made a point of slipping in the occasional traditional performer, the likes of Fred Jordan, Sheila Stewart or earthy singers and musicians from rural East Anglia.

As if this were not commitment enough, Ted always had the confidence to take on ambitious special events: concerts featuring luminaries such as Martin Carthy or Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger (he was from the outset a disciple of MacColl), anniversaries, dances, fundraising nights and musical weekends, with all the effort of organising that entails. In all this he remained untroubled by the constraints of the balance sheet, as if intuitively grasping that what mattered was to have the big night and let any shortfall take care of itself.

Amid the procession of guest singers, Ted's primary aim was to nurture local talent. Very occasionally, this policy threw up exceptional cases, most gratifyingly when singer Mick Ryan and instrumentalist John Burge presented themselves as schoolboys without the price of admission and went on to become distinguished artistes on the circuit. Celebrities aside, Ted was always at pains to acknowledge the great majority of adherents over the years who have simply been out to enjoy a pleasant Friday evening's music.

Although Ted's dedication remained undimmed throughout, it was ultimately the Club's first decade which left the most lasting mark. The 1960s seemed to be one long succession of unforgettable events and defining discoveries, starting with a benefit concert held in St Pancras Town Hall in the summer of 1961 in support of singer and political campaigner Pete Seeger, then a target of McCarthy's witch-hunt in the USA, which provided Ted (and Ivy) with an opportunity to make important contacts within the developing folk movement. In 1964 the Swindon Club staged a weekend school with Cyril Tawney and Bob Davenport, designed to broaden a few horizons. The following year Ted, representing the West of England Folk Music Federation, found himself caught up in the inaugural Keele Festival, which further sharpened his appreciation of the special qualities of traditional performers. Then, in May 1966, Swindon Festival promoters got more than they bargained for when Ted and others decided to enter the 'folk song' competitions with the down-to-earth singing idiom they had been developing. Principal adjudicator was Isobel (later Dame Isobel) Baillie, in her day a renowned international soprano. In an instance of the very reflex musical imperialism Club members were aiming their blow at, she advised Ted to open his mouth wider and look at his audience when singing! The episode seems in retrospect quixotic, but for Ted it was all part of the process of emancipation of the folk revival from the forces of gentility which had held sway before the war. The decade culminated in a weekend festival organised by Ted in the autumn of 1969 to celebrate the work of local song collector Alfred Williams in his native village of South Marston.

Most decisive of all was the chance discovery in the mid-Sixties (no one troubled to record exact dates) of two rare survivals on the very doorstep. The Bricklayers Arms at Longcot near Faringdon was an ungentrified country pub where the villagers still held an uncontrived sing-song at the weekend. A connection was made after the publican's daughter, Kathleen, started going to Swindon Club, resulting in some wonderful nights of singing in the spartan but welcoming bar. Prominent among the locals were irrepressible dialect storyteller George Maisey and singer Bill Whiting, the latter being as a result recorded by John Baldwin and by Mike Yates. Better known but no less (trans)formative was Bampton, with its fabled Morris survival. Ted immediately saw in Bampton the very embodiment of a calendar custom carried on by ordinary country people, consequently having a character unlike anything to be experienced in the revival. As a measure of just how well they fitted in, he and Ivy were invited to join the Bampton (Shergold) team's tour of south-east Ireland in the summer of 1968. They barely missed a Whitsun over the next five decades. To the very end, Ted retained an especial pride in these two associations with residual village junketing.

If these revelations created one or two hardliners among the membership, those who never again tuned a guitar after hearing a pub session in the Eagle at Bampton, Ted was careful not to join them. For all his savouring of the 'real thing', he knew you cannot try to appeal to a wider public from within the citadel of fundamentalism.

If these revelations created one or two hardliners among the membership, those who never again tuned a guitar after hearing a pub session in the Eagle at Bampton, Ted was careful not to join them. For all his savouring of the 'real thing', he knew you cannot try to appeal to a wider public from within the citadel of fundamentalism.

In all these ways, Ted, with Ivy's indispensable support, was making things happen year in and year out. In 2004, with old age finally creeping up on him and his sight failing, he handed on the Secretaryship of the Swindon Club to long-established member Eric Stott. On 11 June 2007, Ted and Ivy received an award marking the 75th anniversary of the EFDSS at a ceremony at Cecil Sharp House, in recognition of all their efforts down the years. They continued to turn out as Club members each week until shortly before Ted's death.

The niche Ted carved out for himself as promoter and charismatic anchorman was sometimes in danger of obscuring his prowess as singer. He was a sensitive interpreter of a repertory of song from country tradition thoughtfully assembled, much of it drawn from unimpeachable sources such as Scan Tester's Lakes of Coalflin (sic), Joe Heaney's Rocks of Bawn or Margaret Barry's Factory Girl. In addition, Ted had a fund of entertaining numbers from the world of popular commercial music which he would produce when he felt the conditions were right. This material derived from contexts pre-dating his entanglement in the folk revival, in particular robust, unselfconscious sing-songs in the RAF, and Ivy's family parties in the classic East End manner, where everyone was expected to do a turn: their animated Sheik of Araby was simply unmatched for exuberant spectacle.

It was this broader take on untutored music-making that enabled Ted to welcome to the membership a number of performers who did not obviously fit received canons of native 'folk' music: jazz duo Fred and Nancy Foote, music hall guv'nor Lucky Luckhurst, and Irishmen Jim Coughlan (Limerick), Sean Burke (Cork) and Pat Casey (Clare), all three of whom had been musically formed before they drifted to England in search of work. It ensured that, under Ted's stewardship, the Swindon Club was caught up in the postwar folk song movement without being exclusively defined by it.

Ted was by temperament a genial extrovert, whose impulse to perform stemmed not from exhibitionism but from natural absence of inhibition. He could hold a room through sheer force of personality without needing to wax authoritarian.

For all his admirable high-mindedness over matters of principle, he possessed the essential knack of not taking himself too seriously. He always relished the expression "Doing a Ted", having the sense of some engaging blunder which added to the conviviality of a musical occasion. He certainly never allowed doctrine to get in the way of a good party.

Warm hearted and without the slightest trace of pretension, Ted and Ivy had a unique ability to inspire affection wherever they went. They bubbled over with enthusiasm at ninety as much as they had in the far off days of the 1960s.

Ted would surely have wanted all who knew him to rejoice in the memory of a long and committed life well lived.

Andrew Bathe - 26.3.18