| Joe Peter MacLean

|

| Back Of Boisdale

|

| Rounder 11661-7060-2

|

| Alex Francis MacKay

|

| Gaelic In the Bow

|

| Rounder 11661-7059-2

|

| John MacDonald

|

| Formerly of Foot Cape Road

|

| Rounder 82161-7051-2

|

| Morgan MacQuarrie with Gordon MacLean

|

| Over the Cabot Trail

|

| Rounder 11661-7041-2

|

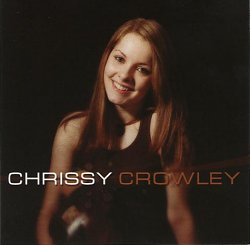

| Chrissy Crowley

|

| Chrissy Crowley

|

| Offshore Gael Music OGCC06

|

All but one of these discs - which illustrate some very contrasting approaches to the Cape Breton fiddle tradition - are part of Rounder’s North American Traditions series, a godsend for lovers of traditional music, which is producing some very valuable releases, by some great traditional musicians that we might otherwise never have had the chance to hear. The two volumes already available of Traditional Fiddle Music of Cape Breton (Rounder 7037 and 7038, reviewed for MT a few years ago by Kerry Blech) offered an indication of the remarkable range of outstanding musicians on the island, and there are further volumes to come, as well as collections such as these, devoted to the work of individual players.

If I have a personal favourite among these discs, it might well be Back Of Boisdale by Joe Peter MacLean, not because he is the most technically skilful of the musicians - in fact, the opposite might be true: he is never remotely flashy, and his playing is less abundantly ornamented than that of the other fiddle-players in this review. But MacLean somehow seems like a natural musician, the kind of local traditional player who learnt his music within the family at home, and his playing is rich enough in character to make technical issues seem much less important. His choice of tunes is delightful, ranging from the old and obscure, to a few by more recent Cape Breton composers such as Dan R MacDonald and Jerry Holland. But it’s evident from the account he provides of his life and background in the booklet that his music has very deep roots; his family were Gaelic speakers, who lived in a remote rural area, and it seems that he didn’t even hear music on the radio until they finally got connected to electricity in the 1960s. His repertoire, as captured here, appears to reach back into very old, even archaic, Scottish traditions. Here are Gaelic songs and rare tunes whose titles were unknown even to the fiddle-player himself, so that they have been called, for the sake of a tracklisting, name such as My Father’s March or Dad’s First Jig. As Mark Wilson notes, this disc offers a view of style and repertoire that pre-dates most of the standardising influences of the last half-century, and - if you felt inclined - you could speculate about the extent to which it might offer that elusive sharper glimpse of the music that the Cape Breton settlers brought from Scotland in the early 1800s. That said, the Medley of Gaelic Songs, which includes the old school songbook stalwart Westering Home (and another air whose name escapes me, but which Dominic Behan later adapted for Liverpool Lou), has a Victorian feel about it, which might suggest that it post-dates the migration.

If I have a personal favourite among these discs, it might well be Back Of Boisdale by Joe Peter MacLean, not because he is the most technically skilful of the musicians - in fact, the opposite might be true: he is never remotely flashy, and his playing is less abundantly ornamented than that of the other fiddle-players in this review. But MacLean somehow seems like a natural musician, the kind of local traditional player who learnt his music within the family at home, and his playing is rich enough in character to make technical issues seem much less important. His choice of tunes is delightful, ranging from the old and obscure, to a few by more recent Cape Breton composers such as Dan R MacDonald and Jerry Holland. But it’s evident from the account he provides of his life and background in the booklet that his music has very deep roots; his family were Gaelic speakers, who lived in a remote rural area, and it seems that he didn’t even hear music on the radio until they finally got connected to electricity in the 1960s. His repertoire, as captured here, appears to reach back into very old, even archaic, Scottish traditions. Here are Gaelic songs and rare tunes whose titles were unknown even to the fiddle-player himself, so that they have been called, for the sake of a tracklisting, name such as My Father’s March or Dad’s First Jig. As Mark Wilson notes, this disc offers a view of style and repertoire that pre-dates most of the standardising influences of the last half-century, and - if you felt inclined - you could speculate about the extent to which it might offer that elusive sharper glimpse of the music that the Cape Breton settlers brought from Scotland in the early 1800s. That said, the Medley of Gaelic Songs, which includes the old school songbook stalwart Westering Home (and another air whose name escapes me, but which Dominic Behan later adapted for Liverpool Lou), has a Victorian feel about it, which might suggest that it post-dates the migration.

Including one solo track (there appears to be a glitch in the track-numbering, but I’m assuming this is Dad’s Second Jig rather than Cead Deireannach Nam Beann), a few with Joe Peter’s regular band The Boisdale Trio, with fiddler Paul Wukitsch and pianist Janet Cameron, and others with Cameron or Gordon MacLean on piano (plus two with the latter on harmonium, at one time a common accompaniment for the fiddle), this album - a little rough round the edges at times, as all the best field recordings should be - is an unadulterated treat from start to finish.

In his 80s, Alex Francis MacKay is more than 20 years senior to Joe Peter MacLean, and while he evidently grew up much more connected to a wider Cape Breton fiddle scene, he also plays music of great traditional depth and character. MacKay spent a few years working in Ontario, but came home when he was laid off from the Chrysler factory, so most of his life has been spent in his home area. Like MacLean, he was brought up speaking Gaelic, and only learnt English at school. To these inexpert ears, it sounds that somewhere in the background of his music the spirit of the pipes looms large; both the way he uses harmonies, through a virtually constant double-stopping technique, and something in his ornamentation, speak of a sensibility somehow informed by the piping tradition, and it is interesting to read in the booklet that one of his sources for tunes has been old pipers’ manuals (among many other tune books, sent from Scotland during World War Two by Dan R MacDonald). There are complexities to this style (in contrast to what seemed like a simpler approach by Joe Peter MacLean), but allowing for the vicissitudes of a live - and probably one-take - recording, MacMay shows himself more than a master of these, and never a slave to them.

In his 80s, Alex Francis MacKay is more than 20 years senior to Joe Peter MacLean, and while he evidently grew up much more connected to a wider Cape Breton fiddle scene, he also plays music of great traditional depth and character. MacKay spent a few years working in Ontario, but came home when he was laid off from the Chrysler factory, so most of his life has been spent in his home area. Like MacLean, he was brought up speaking Gaelic, and only learnt English at school. To these inexpert ears, it sounds that somewhere in the background of his music the spirit of the pipes looms large; both the way he uses harmonies, through a virtually constant double-stopping technique, and something in his ornamentation, speak of a sensibility somehow informed by the piping tradition, and it is interesting to read in the booklet that one of his sources for tunes has been old pipers’ manuals (among many other tune books, sent from Scotland during World War Two by Dan R MacDonald). There are complexities to this style (in contrast to what seemed like a simpler approach by Joe Peter MacLean), but allowing for the vicissitudes of a live - and probably one-take - recording, MacMay shows himself more than a master of these, and never a slave to them.

Again, the emphasis here is on older repertoire, and on showcasing the characteristic style of an outstanding traditional fiddler. MacKay often plays long sets of tunes - several last more than five minutes and a couple more than seven, mostly in a strathspey and reel combination, sometimes preceded by a march or another slow tune (Scott Skinner’s ‘minuet’ Mrs James Christie, for example). His set of airs starting with The Maids of Arrochar is also especially fine. Gordon MacLean provides sympathetic piano acompaniment, although that phrase barely does justice to the role of someone whose contribution is often as melodic as it it harmonic and rhythmic. In the booklet notes Alex Francis MacKay tells some intriguing stories about the musicians he knew when he was learning, like Ronald MacLennan and Gordon MacQuarrie, great musicans and memorable characters, whose skills were often matched by their idiosyncracies. The oral history of traditional music is often almost as entertaining as the music itself, and we are so fortunate that the reminiscences of people like Alex Francis MacKay have been recorded for us to learn from and enjoy - as he says ‘Sometimes I remember what I heard as a kid better than what happened two months ago’. (Mind you, by contrast, Joe Peter MacLean flatly denies having any interesting stories to tell, claiming that his life has been ‘just boring’!).

John L MacDonald is no less a representative of his local traditions, but he sounds to me a little more like a player who has spent time playing with professional and semi-professional musicians. He now lives in Toronto, but was born and brought up in Inverness County where, to quote Mark Wilson’s notes, ‘the most concentrated Gaelic settlement occurred and where fiddle music was most highly cultivated in Cape Breton’. MacDonald exhibits the classic qualities of the Inverness County style, with its distinctive triplets (or ‘cuts’ as they are called by the Cape Breton musicians) and double-stopped harmonies. Nevertheless, it sounds to me that there is something in his playing - a kind of briskness and efficiency - that hints at a certain urbanised influence, maybe a closer familiarity with the music on record, maybe the experience of playing for city dances. This is not a criticism - all the best musicians absorb ingredients into their approach and turn them to their own advantage, and John L MacDonald is an outstanding fiddle player, who produces a distinctive music of great spirit and beauty.

John L MacDonald is no less a representative of his local traditions, but he sounds to me a little more like a player who has spent time playing with professional and semi-professional musicians. He now lives in Toronto, but was born and brought up in Inverness County where, to quote Mark Wilson’s notes, ‘the most concentrated Gaelic settlement occurred and where fiddle music was most highly cultivated in Cape Breton’. MacDonald exhibits the classic qualities of the Inverness County style, with its distinctive triplets (or ‘cuts’ as they are called by the Cape Breton musicians) and double-stopped harmonies. Nevertheless, it sounds to me that there is something in his playing - a kind of briskness and efficiency - that hints at a certain urbanised influence, maybe a closer familiarity with the music on record, maybe the experience of playing for city dances. This is not a criticism - all the best musicians absorb ingredients into their approach and turn them to their own advantage, and John L MacDonald is an outstanding fiddle player, who produces a distinctive music of great spirit and beauty.

One of the things that probably fosters this impression is that this is really a duet album rather than a solo one, with Doug MacPhee’s piano given equal prominence in the recording mix (and sometime more than equal - the Kennedy Street set sounds almost like a piano solo with a fiddler in the background, rather than the other way round). If the pianist was anyone else this might be more of a problem, but MacPhee must surely be one of the greatest ever to embrace traditional music of any kind. On this disc he not only plays the melody along with the fiddle-player, but matches the style of ornamentation as well - quite stunning.

Talking up Doug MacPhee should not be interpreted as denigrating the piano accompaniments of Gordon MacLean (already mentioned for his contribution to Joe Peter MacLean’s and Alex Francis MacKay’s discs), whose own particular abilities are spotlighted in a charming set of jigs for solo piano on Morgan MacQuarrie’s Over The Cabot Road, where he is also the featured accompanist.  MacQuarrie, also from Inverness County, is another musician who has spent much of his life in the city, in his case heading further south and across the border to Detroit. There, although he has participated in local music-making, he has preserved intact his traditional stylings. Remarkably, as Mark Wilson says in the notes ‘… the music heard on this CD is completely consistent, in terms of both technique and ambience, with the oldest recordings we possess from Morgan’s home region.’ Wilson’s detailed description and analysis of MacQuarrie’s style of playing is outstanding, and it’s worth quoting some of it here: ‘The great power and expressiveness of this local style derives from the extremely muscular fashion in which key musical notes get attacked, in such a manner that the bow slightly bounces and skittles across the string, rendering what is usually written as a single note as a compact burr of tones (simultaneous swift ornaments in the left hand augment the effect). Superimposed on this subtle tonal grain are a wide variety of rocking bow motions that supply pulse and articulation to measure-length passages. Together these interlocking patterns of attack lay down a robust rhythmic motif against which the tune’s melodic values are then set, often in a subtly syncopated manner. In effect, a skilled 'folk' player of the old school harnesses a fair degree of what classical violinists would regard as unwanted “bow noise” to supply a rhythmic underpinning for their own playing, which they further augment by continuously tapping out clogging patterns with their feet (Morgan confesses to being unable to play unless he can hear his feet quite loudly).’

MacQuarrie, also from Inverness County, is another musician who has spent much of his life in the city, in his case heading further south and across the border to Detroit. There, although he has participated in local music-making, he has preserved intact his traditional stylings. Remarkably, as Mark Wilson says in the notes ‘… the music heard on this CD is completely consistent, in terms of both technique and ambience, with the oldest recordings we possess from Morgan’s home region.’ Wilson’s detailed description and analysis of MacQuarrie’s style of playing is outstanding, and it’s worth quoting some of it here: ‘The great power and expressiveness of this local style derives from the extremely muscular fashion in which key musical notes get attacked, in such a manner that the bow slightly bounces and skittles across the string, rendering what is usually written as a single note as a compact burr of tones (simultaneous swift ornaments in the left hand augment the effect). Superimposed on this subtle tonal grain are a wide variety of rocking bow motions that supply pulse and articulation to measure-length passages. Together these interlocking patterns of attack lay down a robust rhythmic motif against which the tune’s melodic values are then set, often in a subtly syncopated manner. In effect, a skilled 'folk' player of the old school harnesses a fair degree of what classical violinists would regard as unwanted “bow noise” to supply a rhythmic underpinning for their own playing, which they further augment by continuously tapping out clogging patterns with their feet (Morgan confesses to being unable to play unless he can hear his feet quite loudly).’

There’s much more to Mark’s analysis, but that should give a flavour, both of some of the character of MacQuarrie’s playing and of the quality of the commentary. MacQuarrie also favours long sets of tunes - a number of tracks are more than seven or even eight minutes long - and seems especially skilled in creating effective combinations. There’s an informative breakdown of one of these in the booklet notes as well. Analysis apart, did I forget to mention that this is sixty-seven and a half minutes of non-stop musical pleasure? Well, let’s clear that one up right away: from the poignant slow march Jordan Taylor, to the sheer glee of the Frost Is All Over jig set, this triumphantly affirms our editor’s judgement in a previous review, that Morgan MacQuarrie makes ‘real music, played with joy and relish’.

Having sung the praises of the accompanists, it might seem odd to express the view that as I listened through these discs I sometimes wished that there were a few more opportunities to hear the fiddle entirely solo - there’s one solo track on the Joe Peter MacLean disc, but none on the others. Alex Francis MacKay’s solo Christy Campbell set is one of my favourite tracks on Traditional Fiddle Music Music Vol. 1, and it seems to me to be a way of giving a different kind of insight into a player’s technique, especially how they drive the tunes’ rhythms along. These styles, after all, were developed at a time when there was no piano. OK - I’m looking a gift-horse in the mouth, and I’ll shut up now.

After that line-up of grand old men of Cape Breton music, all of whom learned their art (at least to begin with) at a time before the mass media exerted its baleful standardising influences, it’s interesting to turn to a disc by a 17-year-old whose relationship with communications technologies is very different. Chrissy Crowley has her own website, a presence on MySpace and an electronic press kit at SonicBid. This is the contemporary image-building that we now expect of a young musician, but of course, the proof is in whether the music has substance beyond all this. In Chrissy Crowley’s case, it does. The website might make the most of her visual appeal - she has youth and beauty to spare - but it also emphasises her heritage (granddaughter of two respected fiddlers, and grand-niece of Angus Chisholm, one of the first musicians from the island to record). This is not an album of field recordings, but nor is it some manufactured studio confection. While care has been taken in arrangement and presentation, there are no big production numbers: Crowley plays the tunes, accompanied by piano and/or acoustic guitar, with great skill and accomplishment, whether expressing the beauty of To Daunt Me in the opening set, or generating excitement in the reels in Dodging Potholes. She’s recognisably in the Cape Breton tradition, but also exhibits flourishes that show the - perhaps inevitable - influence of internationally successful Celtic fiddle players from other lineages, particulary Irish. There’s a great deal to celebrate in the fact that Cape Breton music is being carried on in the hands of young musicians like Chrissy Crowley, manifestly respectful of its heritage, while finding ways to keep it contemporary and fresh.

After that line-up of grand old men of Cape Breton music, all of whom learned their art (at least to begin with) at a time before the mass media exerted its baleful standardising influences, it’s interesting to turn to a disc by a 17-year-old whose relationship with communications technologies is very different. Chrissy Crowley has her own website, a presence on MySpace and an electronic press kit at SonicBid. This is the contemporary image-building that we now expect of a young musician, but of course, the proof is in whether the music has substance beyond all this. In Chrissy Crowley’s case, it does. The website might make the most of her visual appeal - she has youth and beauty to spare - but it also emphasises her heritage (granddaughter of two respected fiddlers, and grand-niece of Angus Chisholm, one of the first musicians from the island to record). This is not an album of field recordings, but nor is it some manufactured studio confection. While care has been taken in arrangement and presentation, there are no big production numbers: Crowley plays the tunes, accompanied by piano and/or acoustic guitar, with great skill and accomplishment, whether expressing the beauty of To Daunt Me in the opening set, or generating excitement in the reels in Dodging Potholes. She’s recognisably in the Cape Breton tradition, but also exhibits flourishes that show the - perhaps inevitable - influence of internationally successful Celtic fiddle players from other lineages, particulary Irish. There’s a great deal to celebrate in the fact that Cape Breton music is being carried on in the hands of young musicians like Chrissy Crowley, manifestly respectful of its heritage, while finding ways to keep it contemporary and fresh.

I suggested at the start of this review that I might have a favourite among these discs; in fact, the more I listen to the four Rounder collections, the more obvious it is that any of them - for different reasons each time - could claim that position. That statement pointedly appears to exclude the Chrissy Crowley, but inevitably, there are qualities that a younger musician still needs to grow into, and after years of listening to traditional music, I’ve come to value more and more, perhaps even above all, those characteristics that nowadays rarely seem to transfer between generations. Some of these are intangibles - and at my most cantankerous, I’ll insist that you either hear them or you don’t - but there are also clearly recognisable stylistic qualities, often reflecting a local tradition or a particular group of musicians, or an approach that developed to meet particular circumstances. Either way, it is surely a truism - especially in the pages of this particular journal - to observe that increasing standardisation of approaches to traditional music means that something special, something vital, is lost. If this seems churlish in the context of a review that takes in the first fruits of the endeavors of a brilliantly gifted teenager who has been sufficiently impassioned by traditional music to teach herself to play, and sufficiently steeped in it to produce work that has genuine riches of its own, it isn’t meant to. I get a real kick out of listening to Chrissy Crowley, and wish her a long and very successful musical career, but I’ll still turn, for preference, to the special kinds of satisfaction I get from hearing and experiencing the old, disappearing indigenous styles of musicians like Joe Peter MacLean, Alex Francis MacKay, John MacDonald and Morgan MacQuarrie.

Ray Templeton - 23.8.07

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 23.8.07

If I have a personal favourite among these discs, it might well be Back Of Boisdale by Joe Peter MacLean, not because he is the most technically skilful of the musicians - in fact, the opposite might be true: he is never remotely flashy, and his playing is less abundantly ornamented than that of the other fiddle-players in this review. But MacLean somehow seems like a natural musician, the kind of local traditional player who learnt his music within the family at home, and his playing is rich enough in character to make technical issues seem much less important. His choice of tunes is delightful, ranging from the old and obscure, to a few by more recent Cape Breton composers such as Dan R MacDonald and Jerry Holland. But it’s evident from the account he provides of his life and background in the booklet that his music has very deep roots; his family were Gaelic speakers, who lived in a remote rural area, and it seems that he didn’t even hear music on the radio until they finally got connected to electricity in the 1960s. His repertoire, as captured here, appears to reach back into very old, even archaic, Scottish traditions. Here are Gaelic songs and rare tunes whose titles were unknown even to the fiddle-player himself, so that they have been called, for the sake of a tracklisting, name such as My Father’s March or Dad’s First Jig. As Mark Wilson notes, this disc offers a view of style and repertoire that pre-dates most of the standardising influences of the last half-century, and - if you felt inclined - you could speculate about the extent to which it might offer that elusive sharper glimpse of the music that the Cape Breton settlers brought from Scotland in the early 1800s. That said, the Medley of Gaelic Songs, which includes the old school songbook stalwart Westering Home (and another air whose name escapes me, but which Dominic Behan later adapted for Liverpool Lou), has a Victorian feel about it, which might suggest that it post-dates the migration.

If I have a personal favourite among these discs, it might well be Back Of Boisdale by Joe Peter MacLean, not because he is the most technically skilful of the musicians - in fact, the opposite might be true: he is never remotely flashy, and his playing is less abundantly ornamented than that of the other fiddle-players in this review. But MacLean somehow seems like a natural musician, the kind of local traditional player who learnt his music within the family at home, and his playing is rich enough in character to make technical issues seem much less important. His choice of tunes is delightful, ranging from the old and obscure, to a few by more recent Cape Breton composers such as Dan R MacDonald and Jerry Holland. But it’s evident from the account he provides of his life and background in the booklet that his music has very deep roots; his family were Gaelic speakers, who lived in a remote rural area, and it seems that he didn’t even hear music on the radio until they finally got connected to electricity in the 1960s. His repertoire, as captured here, appears to reach back into very old, even archaic, Scottish traditions. Here are Gaelic songs and rare tunes whose titles were unknown even to the fiddle-player himself, so that they have been called, for the sake of a tracklisting, name such as My Father’s March or Dad’s First Jig. As Mark Wilson notes, this disc offers a view of style and repertoire that pre-dates most of the standardising influences of the last half-century, and - if you felt inclined - you could speculate about the extent to which it might offer that elusive sharper glimpse of the music that the Cape Breton settlers brought from Scotland in the early 1800s. That said, the Medley of Gaelic Songs, which includes the old school songbook stalwart Westering Home (and another air whose name escapes me, but which Dominic Behan later adapted for Liverpool Lou), has a Victorian feel about it, which might suggest that it post-dates the migration.

In his 80s, Alex Francis MacKay is more than 20 years senior to Joe Peter MacLean, and while he evidently grew up much more connected to a wider Cape Breton fiddle scene, he also plays music of great traditional depth and character. MacKay spent a few years working in Ontario, but came home when he was laid off from the Chrysler factory, so most of his life has been spent in his home area. Like MacLean, he was brought up speaking Gaelic, and only learnt English at school. To these inexpert ears, it sounds that somewhere in the background of his music the spirit of the pipes looms large; both the way he uses harmonies, through a virtually constant double-stopping technique, and something in his ornamentation, speak of a sensibility somehow informed by the piping tradition, and it is interesting to read in the booklet that one of his sources for tunes has been old pipers’ manuals (among many other tune books, sent from Scotland during World War Two by Dan R MacDonald). There are complexities to this style (in contrast to what seemed like a simpler approach by Joe Peter MacLean), but allowing for the vicissitudes of a live - and probably one-take - recording, MacMay shows himself more than a master of these, and never a slave to them.

In his 80s, Alex Francis MacKay is more than 20 years senior to Joe Peter MacLean, and while he evidently grew up much more connected to a wider Cape Breton fiddle scene, he also plays music of great traditional depth and character. MacKay spent a few years working in Ontario, but came home when he was laid off from the Chrysler factory, so most of his life has been spent in his home area. Like MacLean, he was brought up speaking Gaelic, and only learnt English at school. To these inexpert ears, it sounds that somewhere in the background of his music the spirit of the pipes looms large; both the way he uses harmonies, through a virtually constant double-stopping technique, and something in his ornamentation, speak of a sensibility somehow informed by the piping tradition, and it is interesting to read in the booklet that one of his sources for tunes has been old pipers’ manuals (among many other tune books, sent from Scotland during World War Two by Dan R MacDonald). There are complexities to this style (in contrast to what seemed like a simpler approach by Joe Peter MacLean), but allowing for the vicissitudes of a live - and probably one-take - recording, MacMay shows himself more than a master of these, and never a slave to them.

John L MacDonald is no less a representative of his local traditions, but he sounds to me a little more like a player who has spent time playing with professional and semi-professional musicians. He now lives in Toronto, but was born and brought up in Inverness County where, to quote Mark Wilson’s notes, ‘the most concentrated Gaelic settlement occurred and where fiddle music was most highly cultivated in Cape Breton’. MacDonald exhibits the classic qualities of the Inverness County style, with its distinctive triplets (or ‘cuts’ as they are called by the Cape Breton musicians) and double-stopped harmonies. Nevertheless, it sounds to me that there is something in his playing - a kind of briskness and efficiency - that hints at a certain urbanised influence, maybe a closer familiarity with the music on record, maybe the experience of playing for city dances. This is not a criticism - all the best musicians absorb ingredients into their approach and turn them to their own advantage, and John L MacDonald is an outstanding fiddle player, who produces a distinctive music of great spirit and beauty.

John L MacDonald is no less a representative of his local traditions, but he sounds to me a little more like a player who has spent time playing with professional and semi-professional musicians. He now lives in Toronto, but was born and brought up in Inverness County where, to quote Mark Wilson’s notes, ‘the most concentrated Gaelic settlement occurred and where fiddle music was most highly cultivated in Cape Breton’. MacDonald exhibits the classic qualities of the Inverness County style, with its distinctive triplets (or ‘cuts’ as they are called by the Cape Breton musicians) and double-stopped harmonies. Nevertheless, it sounds to me that there is something in his playing - a kind of briskness and efficiency - that hints at a certain urbanised influence, maybe a closer familiarity with the music on record, maybe the experience of playing for city dances. This is not a criticism - all the best musicians absorb ingredients into their approach and turn them to their own advantage, and John L MacDonald is an outstanding fiddle player, who produces a distinctive music of great spirit and beauty.

MacQuarrie, also from Inverness County, is another musician who has spent much of his life in the city, in his case heading further south and across the border to Detroit. There, although he has participated in local music-making, he has preserved intact his traditional stylings. Remarkably, as Mark Wilson says in the notes ‘… the music heard on this CD is completely consistent, in terms of both technique and ambience, with the oldest recordings we possess from Morgan’s home region.’ Wilson’s detailed description and analysis of MacQuarrie’s style of playing is outstanding, and it’s worth quoting some of it here: ‘The great power and expressiveness of this local style derives from the extremely muscular fashion in which key musical notes get attacked, in such a manner that the bow slightly bounces and skittles across the string, rendering what is usually written as a single note as a compact burr of tones (simultaneous swift ornaments in the left hand augment the effect). Superimposed on this subtle tonal grain are a wide variety of rocking bow motions that supply pulse and articulation to measure-length passages. Together these interlocking patterns of attack lay down a robust rhythmic motif against which the tune’s melodic values are then set, often in a subtly syncopated manner. In effect, a skilled 'folk' player of the old school harnesses a fair degree of what classical violinists would regard as unwanted “bow noise” to supply a rhythmic underpinning for their own playing, which they further augment by continuously tapping out clogging patterns with their feet (Morgan confesses to being unable to play unless he can hear his feet quite loudly).’

MacQuarrie, also from Inverness County, is another musician who has spent much of his life in the city, in his case heading further south and across the border to Detroit. There, although he has participated in local music-making, he has preserved intact his traditional stylings. Remarkably, as Mark Wilson says in the notes ‘… the music heard on this CD is completely consistent, in terms of both technique and ambience, with the oldest recordings we possess from Morgan’s home region.’ Wilson’s detailed description and analysis of MacQuarrie’s style of playing is outstanding, and it’s worth quoting some of it here: ‘The great power and expressiveness of this local style derives from the extremely muscular fashion in which key musical notes get attacked, in such a manner that the bow slightly bounces and skittles across the string, rendering what is usually written as a single note as a compact burr of tones (simultaneous swift ornaments in the left hand augment the effect). Superimposed on this subtle tonal grain are a wide variety of rocking bow motions that supply pulse and articulation to measure-length passages. Together these interlocking patterns of attack lay down a robust rhythmic motif against which the tune’s melodic values are then set, often in a subtly syncopated manner. In effect, a skilled 'folk' player of the old school harnesses a fair degree of what classical violinists would regard as unwanted “bow noise” to supply a rhythmic underpinning for their own playing, which they further augment by continuously tapping out clogging patterns with their feet (Morgan confesses to being unable to play unless he can hear his feet quite loudly).’

After that line-up of grand old men of Cape Breton music, all of whom learned their art (at least to begin with) at a time before the mass media exerted its baleful standardising influences, it’s interesting to turn to a disc by a 17-year-old whose relationship with communications technologies is very different. Chrissy Crowley has her own website, a presence on MySpace and an electronic press kit at SonicBid. This is the contemporary image-building that we now expect of a young musician, but of course, the proof is in whether the music has substance beyond all this. In Chrissy Crowley’s case, it does. The website might make the most of her visual appeal - she has youth and beauty to spare - but it also emphasises her heritage (granddaughter of two respected fiddlers, and grand-niece of Angus Chisholm, one of the first musicians from the island to record). This is not an album of field recordings, but nor is it some manufactured studio confection. While care has been taken in arrangement and presentation, there are no big production numbers: Crowley plays the tunes, accompanied by piano and/or acoustic guitar, with great skill and accomplishment, whether expressing the beauty of To Daunt Me in the opening set, or generating excitement in the reels in Dodging Potholes. She’s recognisably in the Cape Breton tradition, but also exhibits flourishes that show the - perhaps inevitable - influence of internationally successful Celtic fiddle players from other lineages, particulary Irish. There’s a great deal to celebrate in the fact that Cape Breton music is being carried on in the hands of young musicians like Chrissy Crowley, manifestly respectful of its heritage, while finding ways to keep it contemporary and fresh.

After that line-up of grand old men of Cape Breton music, all of whom learned their art (at least to begin with) at a time before the mass media exerted its baleful standardising influences, it’s interesting to turn to a disc by a 17-year-old whose relationship with communications technologies is very different. Chrissy Crowley has her own website, a presence on MySpace and an electronic press kit at SonicBid. This is the contemporary image-building that we now expect of a young musician, but of course, the proof is in whether the music has substance beyond all this. In Chrissy Crowley’s case, it does. The website might make the most of her visual appeal - she has youth and beauty to spare - but it also emphasises her heritage (granddaughter of two respected fiddlers, and grand-niece of Angus Chisholm, one of the first musicians from the island to record). This is not an album of field recordings, but nor is it some manufactured studio confection. While care has been taken in arrangement and presentation, there are no big production numbers: Crowley plays the tunes, accompanied by piano and/or acoustic guitar, with great skill and accomplishment, whether expressing the beauty of To Daunt Me in the opening set, or generating excitement in the reels in Dodging Potholes. She’s recognisably in the Cape Breton tradition, but also exhibits flourishes that show the - perhaps inevitable - influence of internationally successful Celtic fiddle players from other lineages, particulary Irish. There’s a great deal to celebrate in the fact that Cape Breton music is being carried on in the hands of young musicians like Chrissy Crowley, manifestly respectful of its heritage, while finding ways to keep it contemporary and fresh.