Musical Traditions of Portugal

Various Artists

Smithsonian Folkways CD SF 40435

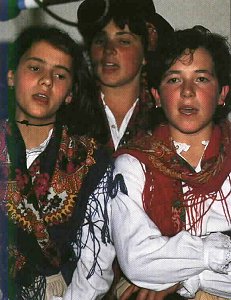

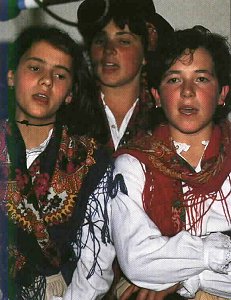

This is Volume 9 in a series of 'The World's Musical Traditions' which, to quote the slipcase, are 'edited by the International Institute for Traditional Music, Berlin, in co-operation with the International Council for Traditional Music (UNESCO)'.  The disc contains recordings made in March and April 1988, and is accompanied by an exemplary 76 page booklet, containing notes in English and Portuguese, lyric transcriptions, photographs, and the thing of whose absence I so often complain, a map of recording locations.

The disc contains recordings made in March and April 1988, and is accompanied by an exemplary 76 page booklet, containing notes in English and Portuguese, lyric transcriptions, photographs, and the thing of whose absence I so often complain, a map of recording locations.

Now one of the comparatively less prosperous nations of Europe, Portugal was once a great maritime and imperial power, and that history has left linguistic and cultural traces in Africa, South America and the Far East; Madeira and the Azores are still Portuguese territory. Continental Portugal's borders have been stable since the 13th Century, and although modernisation is making the country more uniform, and changing traditional lifestyles, there is still considerable cultural diversity among the different regions. From 1926 to 1974, Portugal was governed by the longest enduring of all Fascist regimes; as the CD's annotator and field recordist Salwa El-Shawan Castelo-Branco points out, the Estado Novo sought to promote an image of the country, to itself and the outside world alike, as "a predominantly rural community happily immersed in its traditions," and used folk music as one of its means to this end. It is perhaps not surprising that for many years there was considerable hostility towards folclore among intellectuals and musicologists.

The 30 tracks on the disc come from six regions of Portugal. The first six were recorded in the north-east, in three villages which lie close to the Spanish border, and until recently were very isolated. The music of the region has close affinities with that across the border, and the laços (stick dances) of the area are thought to be of Castilian origin. There are nearly 60 laços, each with a distinct tune and dance; they are played at religious and secular festas, and most also have texts associated with them, either in the local dialect, Mirandês, or in Castilian. For example, Señor Mío, played at religious festivals, has a text which begins: Señor mío, Jesucristo/Dios y hombre verdadero/Creador y Redentor/Y salvador del cielo y tierra.  Normally, however, the text is only sung at rehearsals or if no instruments are available. Here, Señor Mío is played by bagpipes, snare drum and bass drum. (sound clip) Also accompanied by snare and bass drums is the tamborileiro ensemble of flauta and tamboril (fife and tabor, played by one musician), which will intrigue anyone familiar with the fife and drum bands of Mississippi. The north-eastern tracks are rounded off by a melancholy ballad of kidnap and rape, Os Soldados Violadores.

Normally, however, the text is only sung at rehearsals or if no instruments are available. Here, Señor Mío is played by bagpipes, snare drum and bass drum. (sound clip) Also accompanied by snare and bass drums is the tamborileiro ensemble of flauta and tamboril (fife and tabor, played by one musician), which will intrigue anyone familiar with the fife and drum bands of Mississippi. The north-eastern tracks are rounded off by a melancholy ballad of kidnap and rape, Os Soldados Violadores.

The Castelo Branco region of east central Portugal is represented by recordings from the village of Monsanto, which despite its isolation and small population, is well known in the country as the winner of the competition to find "The Most Portuguese of All Villages", organised by the Estado Novo in 1938. Villages "had to demonstrate their resistance to outside influences and "preserve the highest degree of purity" in their traditions." Dubious though the motivation behind this exercise was, it had the effect, which persists to this day, of making the people of Monsanto very conscious of their traditions, and of the importance of preserving them.  The typical music of the region is choral, as on Marcelada, about meeting one's beloved after picking marcela, a wild herb. Marcelada is sung by eight women, two of whom also play adufes, the square frame drums introduced by the Arabs in the 8th to 12th centuries. These instruments are exclusively played by women,

The typical music of the region is choral, as on Marcelada, about meeting one's beloved after picking marcela, a wild herb. Marcelada is sung by eight women, two of whom also play adufes, the square frame drums introduced by the Arabs in the 8th to 12th centuries. These instruments are exclusively played by women,  who hold it with their thumbs and one index fingers, striking the skin with the remaining fingers. (sound clip)

who hold it with their thumbs and one index fingers, striking the skin with the remaining fingers. (sound clip)

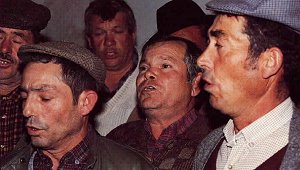

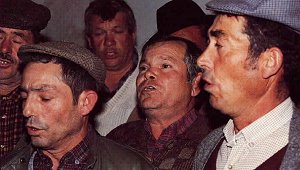

Alentejo in the south of Portugal is also the home of a choral music, sung by both male and female choirs. Cante is an unaccompanied, and not very complex, polyphony, begun by a soloist (ponto), who is succeeded by another soloist (alto), who sings a third or a tenth above the ponto. As the alto ornaments the melody, the chorus (baixos) joins in. Cante is sung in settings ranging from formally structured, costumed groups with a name and a director, to homes, picnics and during agricultural work.  Whatever its setting, cante is an important part of Alentejano identity, whether sung in the fast syllabic style characteristic of the left bank of the Guadiana, or the slow, highly ornamented style of the right bank,

Whatever its setting, cante is an important part of Alentejano identity, whether sung in the fast syllabic style characteristic of the left bank of the Guadiana, or the slow, highly ornamented style of the right bank,  heard in this example, Ao Romper da Bela Aurora (At the Break of the Beautiful Dawn). (sound clip)

heard in this example, Ao Romper da Bela Aurora (At the Break of the Beautiful Dawn). (sound clip)

Probably the most familiar sound on this disc will be that of the guitarradas, part of cançao de Coimbra, the lyrical tradition of sung (balada, fado) and instrumental (guitarrada) music that forms an integral part of the academic calendar of the mediaeval University of Coimbra. Can there be anywhere else in the world a music of undoubtedly folkloric character, but which is mainly the province of university students, alumni and professors?  If there is, can it have produced anything as lovely as the late António Portugal's Valsa para o Tempo que Passou (Waltz for the Times that are Past and Gone)? (sound clip)

If there is, can it have produced anything as lovely as the late António Portugal's Valsa para o Tempo que Passou (Waltz for the Times that are Past and Gone)? (sound clip)  The instruments heard on this 'old time waltz' are two guitarras, an adaptation of the cittern which entered Portugal in the 18th Century through the sizable English colony which played an important role in the port wine trade of Oporto.

The instruments heard on this 'old time waltz' are two guitarras, an adaptation of the cittern which entered Portugal in the 18th Century through the sizable English colony which played an important role in the port wine trade of Oporto.

The CD's final nine tracks are performed by three ranchos folclóricos, one from the Tagus Valley, and two from the northwest. The ranchos are formally constituted groups of singers, dancers and musicians, consciously performing in a revivalist tradition that began in the teens and twenties of this century. The ranchos folclóricos were among the manifestations of tradition which were hijacked by the Estado Novo for ideological purposes, but since the 1980s they have shaken off the taint of this association, and are now widespread, both in Portugal and among emigré communities. The standard instrumentation of many ranchos consists of accordions and triangle, both of which can be heard on this couple dance;  also featured here are clarinet, viola, and percussion, produced by cântaro com abano (a clay pot, struck with a fan) and cana (a reed idiophone that produces the claves-like sounds). (sound clip)

also featured here are clarinet, viola, and percussion, produced by cântaro com abano (a clay pot, struck with a fan) and cana (a reed idiophone that produces the claves-like sounds). (sound clip)

It will be obvious that Portugal sustains a rich variety of traditional music, some of it still an integral part of a traditional way of life, some of it the result of conscious processes of preservation, and some of it partaking of both attributes. It also seems evident that, whatever dubious attempts at political co-option were made in the past, traditional music, revivalist and otherwise, is an important marker of both national and regional identities. I'm well aware, of course that, in fulfilling those roles, Portuguese traditional music must have political dimensions and implications, which are doubtless of considerable importance to the democratic regimes that have happily succeeded the long rule of the military; but it seems likely that the mechanisms by which ideology interacts with folklore are considerably healthier and more respectful now than in former times. It's also clear that, both for their variety and their quality, Portugal's folk musics are among the most interesting and enjoyable to be heard in Europe.

Chris Smith - 30.4.98

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 9.11.02

The disc contains recordings made in March and April 1988, and is accompanied by an exemplary 76 page booklet, containing notes in English and Portuguese, lyric transcriptions, photographs, and the thing of whose absence I so often complain, a map of recording locations.

The disc contains recordings made in March and April 1988, and is accompanied by an exemplary 76 page booklet, containing notes in English and Portuguese, lyric transcriptions, photographs, and the thing of whose absence I so often complain, a map of recording locations.

The typical music of the region is choral, as on Marcelada, about meeting one's beloved after picking marcela, a wild herb. Marcelada is sung by eight women, two of whom also play adufes, the square frame drums introduced by the Arabs in the 8th to 12th centuries. These instruments are exclusively played by women,

The typical music of the region is choral, as on Marcelada, about meeting one's beloved after picking marcela, a wild herb. Marcelada is sung by eight women, two of whom also play adufes, the square frame drums introduced by the Arabs in the 8th to 12th centuries. These instruments are exclusively played by women,  Whatever its setting, cante is an important part of Alentejano identity, whether sung in the fast syllabic style characteristic of the left bank of the Guadiana, or the slow, highly ornamented style of the right bank,

Whatever its setting, cante is an important part of Alentejano identity, whether sung in the fast syllabic style characteristic of the left bank of the Guadiana, or the slow, highly ornamented style of the right bank,  The instruments heard on this 'old time waltz' are two guitarras, an adaptation of the cittern which entered Portugal in the 18th Century through the sizable English colony which played an important role in the port wine trade of Oporto.

The instruments heard on this 'old time waltz' are two guitarras, an adaptation of the cittern which entered Portugal in the 18th Century through the sizable English colony which played an important role in the port wine trade of Oporto.