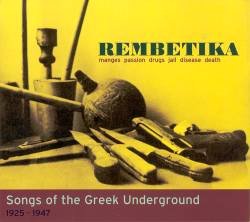

Rembetika

Songs of the Greek Underground 1925-1947

Trikont US-0293

The setting looks like a narrow back alley, or maybe a covered market; it's difficult to be sure. There are stalls on either side, some with shutters open, others closed over. Into the space a large group of men are crowded, standing, sitting, squatting.  The

ones at the front are clutching their instruments - bouzoukis of various sizes, a guitar, a mandolin, some baglamas - the others probably just looking for a bit of the limelight, some reflected glory. Their clothes don't tell us much - some are sharply dressed, with polished shoes gleaming, others seem clad in makeshift combinations that could either speak of lack of funds or a cultivated bohemian look. There are

straw hats and a few caps, and several bare heads. The musicians expressions are all much the same, a solemn, maybe even sullen expression, and their heads inclined very slightly forward so that they seem to be looking out from under heavy brows, suggesting a defiance as well. The unavoidable impression is of intensity, earnestness and unshakeable confidence - these are men who take their music seriously, who live it and take deep pride in it. Even in this crowd, each man exudes a sense of individualism and self-sufficiency. These are the rembetes, or the manges, the players and singers who made this music of the Greek underworld - songs, as a strapline on the front of this anthology puts it succinctly, if rather bluntly, of manges, passion, drugs, jail, disease, death.

The

ones at the front are clutching their instruments - bouzoukis of various sizes, a guitar, a mandolin, some baglamas - the others probably just looking for a bit of the limelight, some reflected glory. Their clothes don't tell us much - some are sharply dressed, with polished shoes gleaming, others seem clad in makeshift combinations that could either speak of lack of funds or a cultivated bohemian look. There are

straw hats and a few caps, and several bare heads. The musicians expressions are all much the same, a solemn, maybe even sullen expression, and their heads inclined very slightly forward so that they seem to be looking out from under heavy brows, suggesting a defiance as well. The unavoidable impression is of intensity, earnestness and unshakeable confidence - these are men who take their music seriously, who live it and take deep pride in it. Even in this crowd, each man exudes a sense of individualism and self-sufficiency. These are the rembetes, or the manges, the players and singers who made this music of the Greek underworld - songs, as a strapline on the front of this anthology puts it succinctly, if rather bluntly, of manges, passion, drugs, jail, disease, death.

All the writers about rembetika like to tell us that the rembetes loved their music, their bouzoukis, their hash pipes and their fashionable clothes. What is also apparent is that they loved the camera as well. Photographs abound of these restless, haunted-looking men and women, instruments in hands, eyes fixed intently on the lens. This might just have been an aspect of their legendary self-possession (or self-obsession, maybe), but it's difficult to shake off a sense that they seemed to recognise that what they were doing was important and they wanted it to be captured visually, as well as aurally. That so many of the photographs are not studio portraits (although there are plenty of

those as well), but informally set up in tavernas, on street corners and back alleys, also suggests that they felt that it was important to be portrayed in their natural environment, a kind of acknowledgment that this is where they and their music belonged, that these humble locations had a meaning and significance of their own. In these pictures, the paraphernalia - instruments, smoking equipment, clothes - assume a

symbolic character not unlike the objects with which 17th century portrait painters surrounded their sitters.

The subtitle is not far wrong. Disc One seems dedicated to dope songs - the titles of first three tracks, for example, translate respectively as The pain of the junkie; I am a junkie and When we were smoking dope one evening and the remainder are not much different. You might scarcely credit that a subject of that kind could produce songs of such grace and ethereal power as Stellakis's Htes to Vradi sto Teke mas or such stately beauty as Rita Ambadsi's Hanumakia , but in the hands of these Greek musical enchanters, it could do that and more, again and again. Disc Two casts its net a little more widely. It begins with an instrumental, by Ioannis Halkias aka Jack Gregory, one of the earliest bouzouki instrumental records, from 1932 Minore Tu Teke . Having said that, it should be noted that a teke is word for a hashish den, so it isn't that much of a departure from the previous content . But Rosa Eskenazi sings of prison - in a stunning Cafe Aman style song that speaks volumes for the fact that one of main strands of this music was imported by Greek exiles from Turkey - Panajiotis Toundas recounts a Conversation with Death , and Kostas Roukounas sings to his mother that he's dying of tuberculosis. Even without full translations of the lyrics, you know that often these gloomy subjects are being explored with characteristic wit and swagger - Dimitris Atraidis tells of a conversation in which some Meraklides ask Charon how the drunkards manage in Hades without wine (to quote from the booklet notes), while Papaioannou imagines five Greeks in the afterlife converting hell to the lifestyle of the Rembetes. Nevertheless, fatalism and despair are among of the key characteristics of these songs - Hadsichristos (a particular favourite of the present writer, on the second latest recording included, from 1946) has little to be witty about as he is stricken by tuberculosis and waiting for his own death in a sanatorium in the mountains - a far cry from relaxing with a waterpipe in a hash den in sunny Piraeus.

Because it is a music deeply rooted in the land and the peoples from which it grew - seamlessly weaving elements of both Western and middle-Eastern traditions - it is easy to forget that in these years (between the mid 1920s and the mid 1940s, although the vast majority of these tracks were recorded in the 1930s, a decade that saw a concentrated outpouring of recordings) rembetika was a new music, recently born and very much still in development, carving out its own distinctive identity against a background of increasing global cultural homogenisation. It was, to rely on cliche, a golden age for the music, when so many of rembetika's giants were in their prime - Stellakis, Katsaros, Stratos, Eskenazi (all represented here) and perhaps most important of all, Markos Vamvakaris. In the photograph described at the beginning of this article, Markos stands out from the crowd - he's dead centre, one hand clutching the head of a guitar that is slung casually over his shoulder, the other reaching out in front of him in a gesture that suggests that maybe he's directing things from in front of the camera. It's fitting - his position in the history of rembetika is also dead centre, and hugely influential. He gets five tracks on this compilation and we have ample opportunity to assess his greatness; his skills as a bouzouki player, his rough, tough voice so redolent of all that these songs stand for - a life spent in smoky joints, late nights and damp, unhealthy lodgings. Markos sings his own story in The Dope Head, described in the notes as the most important hassiklido song in the history of rembetika , while in All the Rembetes in this World , he reflects on his position in that forbidding, if fascinating demi-monde. While one might only regret the absence of one of his superb instumentals, there are plenty of opportunities to enjoy his extraordinary, precise skills and dazzling musical invention.

The bouzouki wasn't the only instrument of rembetika, and while the guitar was often used simply for rhythmic or harmonic accompaniment (witness, for example, the arpeggios to be heard behind Halkias's bouzouki solo, disc 2 track 1) it could also be a lead voice in its own right - Jiorgos Katsaros was one of rembetika's finest guitarists, picking the melodies with his fingers, with delicate harmonies that emphasised the music's European ingredients. He gets three tracks - two about dope and one about TB. The last of these is especially poignant and beautiful, despite its harrowing content, but the other two are irresistible. The other characteristic instrument was the baglamas - like a shrunken version of the bouzouki - and its most celebrated exponent was Jiorgos Batis. While its characteristic chiming can be heard on many tracks, Batis has two tracks on the first disc and one on the second, on which to highlight the instrument. His The Prison of Oropos weaves a tale of life in jail, and the cast of low-lifes and renegades that are to be found there. Papazoglou and Stellakis tell of one particular variety of these, the pickpockets, in a beautiful recording that features another important rembetika instrument, the santouri, or hammer dulcimer.

The two CDs come in a handsome double package, with a relevant illustrations, including a vintage print of an aerial view of the port of Salonika, and two separate booklets, with substantial annotations - biographical as well as musical and lyrical. These are in German, although the first booklet also includes a brief summary of each track's content in English. There are also many photographs. The one I described at the beginning of this review appears on the front of Booklet #1. The one on the front of Booklet #2 looks like it was taken in the same place, although evidently at a quite different time, as the people featured are all different. While only one of these seems to be a musician, the photo captures a similar atmosphere, although perhaps these men are a few glasses further on their way to good humour. Many of these photos will be familiar to anyone who already has some rembetika LPs, CDs or books, but they are an essential element of a package like this. To end by going back to where this review began, these men - and they are mostly men - knew that their time was now, but maybe they also knew, consciously or unconsciously, that their time was short, and wanted to ensure that they would leave behind them a visual and aural legacy to shore against their mortality. Maybe that's to read too much into a pile of dusty old records and faded old photographs, rescued from oblivion by a dedicated group of enthusiasts and fantasists, and lovingly assembled for us through digital media. Either way, it's a priceless legacy, and this release offers one of the most attractive and detailed opportunities currently available to experience and enjoy it.

Ray Templeton - 15.9.03

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 15.9.03

The

ones at the front are clutching their instruments - bouzoukis of various sizes, a guitar, a mandolin, some baglamas - the others probably just looking for a bit of the limelight, some reflected glory. Their clothes don't tell us much - some are sharply dressed, with polished shoes gleaming, others seem clad in makeshift combinations that could either speak of lack of funds or a cultivated bohemian look. There are

straw hats and a few caps, and several bare heads. The musicians expressions are all much the same, a solemn, maybe even sullen expression, and their heads inclined very slightly forward so that they seem to be looking out from under heavy brows, suggesting a defiance as well. The unavoidable impression is of intensity, earnestness and unshakeable confidence - these are men who take their music seriously, who live it and take deep pride in it. Even in this crowd, each man exudes a sense of individualism and self-sufficiency. These are the rembetes, or the manges, the players and singers who made this music of the Greek underworld - songs, as a strapline on the front of this anthology puts it succinctly, if rather bluntly, of manges, passion, drugs, jail, disease, death.

The

ones at the front are clutching their instruments - bouzoukis of various sizes, a guitar, a mandolin, some baglamas - the others probably just looking for a bit of the limelight, some reflected glory. Their clothes don't tell us much - some are sharply dressed, with polished shoes gleaming, others seem clad in makeshift combinations that could either speak of lack of funds or a cultivated bohemian look. There are

straw hats and a few caps, and several bare heads. The musicians expressions are all much the same, a solemn, maybe even sullen expression, and their heads inclined very slightly forward so that they seem to be looking out from under heavy brows, suggesting a defiance as well. The unavoidable impression is of intensity, earnestness and unshakeable confidence - these are men who take their music seriously, who live it and take deep pride in it. Even in this crowd, each man exudes a sense of individualism and self-sufficiency. These are the rembetes, or the manges, the players and singers who made this music of the Greek underworld - songs, as a strapline on the front of this anthology puts it succinctly, if rather bluntly, of manges, passion, drugs, jail, disease, death.