Therefore, I had always thought that these mercilessly mutilated extracts were his doing. I don't know about the rest of the series, but none of these presumptions holds here.

Therefore, I had always thought that these mercilessly mutilated extracts were his doing. I don't know about the rest of the series, but none of these presumptions holds here.

The Alan Lomax Collection; World Library of Folk and Primitive Music. Vol XVII

Compiled and edited by Alan Lomax

Rounder 1759

"Green of the corn blight. On yonder hilltop it has rained and drizzled for the last three days and it gets no better. Yesterday, like a man accursed, lovan Iorgovan arose, the son of a shepherd, of a mountaineer, of a larch tree. God damn him. He was a terrible hero! He has heard it said that beyond the mountain is a coiled snake, a monstrous snake. When it roams the countryside it snatches up a heifer or a fat cow, or a beautiful maiden. It eats at one meal as much as it would take [a man] a summer to hunt. Wondrous to behold. So what did lovan do? Started on his way on Thursday morning in the dew and fog; fog at his back and dew at his feet. Wondrous to behold! With his bitch ahead of him he marched straight on. With his hounds on his leash he went at a great pace. Hawk on his fist, he goes his wondrous way......."Well, that's what it says. For a while now, I have harboured a private notion that the Columbia World Library was the part of the Alan Lomax deal which Rounder didn't want. They had, so my ruminations remonstrated, been stuck with it, as the ineluctable part of an agreement which embraced more salable properties, such as Southern Journey and Portraits. From whence hails this impression? Well, even in my most charitable moments, and there are few enough of those these days, I could not describe the Library as anything other than a dated and disastrous exercise in tape editing. For the most part it is made up of minuscule extracts, which are so short that they cannot begin to convey what this music is about. Rectification of that exercise would have meant scouring the globe for news of long dead professors of folklore and ethnomusicology. It would have meant trailing through endless archives of folksong, and sifting through innumerable reels of decayed and fragile acetate tape.Iovan Iorgovan. From track 24 of this disc.

It would have meant a task of epic proportions. Therefore, Rounder's way out appeared not to lie in spending a fortune refurbishing the discs. Far easier to hang the label 'Historic' on the series and issue it as it stood, thereby hoping that it wouldn't lose too much money. That is presumption number one. Presumption number two logically says that it would have been better not to have re-issued the Library at all.

Presumption number three involves identifying the individual responsible. Now, the booklet headings describe Alan Lomax as the Library's Compiler and Editor, and he was certainly its originator.  Therefore, I had always thought that these mercilessly mutilated extracts were his doing. I don't know about the rest of the series, but none of these presumptions holds here.

Therefore, I had always thought that these mercilessly mutilated extracts were his doing. I don't know about the rest of the series, but none of these presumptions holds here.

To begin with, as the excellent discourse by Speranta Rãdulescu ![]() 1 , the editor of the present edition, establishes, the original LP was not in the first instance, edited or compiled by Alan Lomax. It was the work of Tiberiu Alexandru of the Folklore Institute, Bucharest, with a little help from his friend A L Lloyd. It is not clear how much assistance came from Lloyd. However, I'd guess that he was responsible for the translations, and that a fair bit of his remarkable knowledge went into the background information. Lomax, as general editor for the series, deserves undeniable credit for the disc's existence. Nevertheless, I would have thought it courtesy to have given Messrs. Alexandru and Lloyd a higher profile than the brief mention they get in the fine print.

1 , the editor of the present edition, establishes, the original LP was not in the first instance, edited or compiled by Alan Lomax. It was the work of Tiberiu Alexandru of the Folklore Institute, Bucharest, with a little help from his friend A L Lloyd. It is not clear how much assistance came from Lloyd. However, I'd guess that he was responsible for the translations, and that a fair bit of his remarkable knowledge went into the background information. Lomax, as general editor for the series, deserves undeniable credit for the disc's existence. Nevertheless, I would have thought it courtesy to have given Messrs. Alexandru and Lloyd a higher profile than the brief mention they get in the fine print.

For that matter, I'd have thought Ms Rãdulescu's work in updating this volume, deserved a more up front mention than it actually gets. Amongst many other things, she has penned an extremely well thought out new introduction. This includes a couple of interesting explanations for the whistle-stop approach to early anthologies like the Columbia. First of all, she says that the policy of cramming on short excerpts was adopted to enhance the salability of unfamiliar sounding music. That is fairly common knowledge and we need to remember that Lomax was dealing with a mainstream record company, which otherwise showed little interest in ethnic music. In 1960, Columbia's leading artists included singers of romantic ballads, like Andy Williams and Tony Bennett, as well as a jazz pianist, name of Dave Brubeck. The latter had, though, made quite a name for himself by experimenting with unusual time signatures; the sort you were more likely to hear in a Romanian kitchen than a New York nightclub.

But there's more. Ms Rãdulescu goes on to tell us that editors frequently found their options restricted by the material available to them. In other words, they were forced to use short extracts, because that was all collectors of the period were in the habit of taking. This, apparently, was because they were used to using short run cylinders or discs and had not yet adapted to the more flexible medium of recording tape; or the possibilities it opens up for capturing extended renditions. I can see her point, but I would have thought cost to have been another factor. The earliest recorders ran at fifteen inches per second, gobbling up a one inch wide tape which, by today's standards was phenomenally expensive. In a near third world economy like Romania's, recording tape was not a commodity to be wasted.

With presumptions one and three firmly demolished, I am delighted to scotch any rumours that No XVII in the Columbia World Library is not worth revisiting. With appropriate editorial attention, it is become a most interesting example of an up to date refurbishment of period architecture. It must, as all good property agents insist, be experienced to be appreciated. The most noticeable improvement lies in the fact that the playing time has been extended to just over sixty five minutes. I do not possess a copy of the LP version, but I imagine that improves the living space by about thirty per cent. Also, the furniture has been moved around a bit, so that the original track sequencing no longer applies. I cannot tell whether this makes the edifice any airier. However, I am delighted that several apparatchik 'folk orchestras' - included in the original to keep Party bureaucrats happy - have been evicted. Moreover, the aggregated living space has been used to accommodate further examples of genuine popular culture. Finally, the recordings were made over a fair swathe of time; between 1934 and 1957, to be precise. Yet the sound is clear and consistent throughout.

How fares the accommodation now? Well, there is still some evidence of overcrowding, but the new arrangements do leave a little room to breathe.  The present thirty five tracks mean an average of nearly two minutes playing time; give or take the fact that one track is almost eight minutes long. Even so, the kaleidoscope feeling, which other editions of the Library engender, is for the most part minimised. In only one or two cases, e.g. a blistering piece of piping which comes to a maddening halt after forty six seconds, did I feel like screaming 'we wuz robbed'. The fittings include some stunning photographs, as well as the usual song notes, plus song transcriptions in Romanian, with translations into English. In addition to Ms Rãdulescu's thought provoking essay, Alexandru's original LP introduction has been retained intact. It is brief, but concise and well worth reading, even if the tone is a little outmoded in places; and there is an occasional whiff of the folkloristic idealism, which A L Lloyd was prone to suffer from. If nothing else gave the age of this production away, the invocation of Brubeck's time signatures certainly did. Blue Rondo Ala Romania?

The present thirty five tracks mean an average of nearly two minutes playing time; give or take the fact that one track is almost eight minutes long. Even so, the kaleidoscope feeling, which other editions of the Library engender, is for the most part minimised. In only one or two cases, e.g. a blistering piece of piping which comes to a maddening halt after forty six seconds, did I feel like screaming 'we wuz robbed'. The fittings include some stunning photographs, as well as the usual song notes, plus song transcriptions in Romanian, with translations into English. In addition to Ms Rãdulescu's thought provoking essay, Alexandru's original LP introduction has been retained intact. It is brief, but concise and well worth reading, even if the tone is a little outmoded in places; and there is an occasional whiff of the folkloristic idealism, which A L Lloyd was prone to suffer from. If nothing else gave the age of this production away, the invocation of Brubeck's time signatures certainly did. Blue Rondo Ala Romania?

Which reminds me that we need to take five while I discuss the track listings. These have been demarcated by musical type, rather than by region and this might strike the listener as an odd procedure. However, it is one of the factors which gives the production its feelings of stability.

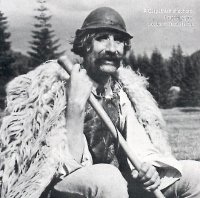

The disc opens with a fanfare played on the tulnic, by Iona Bud. I presume that is her in the cover photograph, although I could find no accreditation in the packaging. The title of this piece is Semnal de Primãvãvra, which the booklet renders into English as 'Signal for Spring'. It is a seminal introduction for a couple of reasons. First of all, I was interested to note that the Romanian word for Spring is almost the same as the Italian; Primavera. Moreover, the tulnic, which readers may know better as the bucium, is here referred to as the alphorn. That is apt, although slightly misleading, for the instrument is an integral part of Romanian folk culture. Nevertheless, I found myself wondering whether this is a case of diffusion, or whether the two instruments evolved independent of each other, perhaps in response to local geography.

Our Spring fanfare leads into a block of ritual songs and melodies. Again, my mind stumbled over the etymology, for a couple of these tracks are referred to as Colindãs. That turns out to be the Romanian for carol and it probably ties in with our word calendar. Again I, more ignoramus than expert, but I have seen the word kalendar used in conjunction with ritual songs from as far away as the Iberian peninsula. That suggests a wide and ancient distribution.

There is no need to make too much of this. Tracing the diffusion or the origins of songs or music or other pieces of folklore, is a fruitless exercise which serious scholars cured themselves of several generations ago. Nevertheless, if I attach just a little significance to these cogitations, it is because they remind us that Romania has an ancient history. Its centrality means that, down through the ages, it has been a stopping place for adventurers and conquerors on the road to everywhere. Small wonder that Romanian folklore is blessed with such riches.

In fact, the ritual section, encompassing four calendar pieces, plus a rainmaking song, plus two funeral laments, plus a wedding song, is too brief to convey the startling variety of Romanian peasant custom; or the significant element which ritual must have represented in Romanian peasant life. The seeker after riches must proceed through these tracks, into the section on dance music. The gems here are rich and rare, but avoid being too dazzled, for it is in these caverns that our forty six second piping excerpt lurks. Moreover, it has a mate, in the form of a song dance from Transylvanya, and that one is only ten seconds longer. ![]() When you have done with these truncations, negotiate your way through a single, haunting example of a shepherd's melody, played on the caval or end blown flute. It is extraordinarily beautiful; its shifting rhythms evoke occasional memories of Dave Brubeck (sound clip - Cãnd Ciobanal si-a Pierdut Ole [When the Shepherd Lost His Sheep] - Neculi Taftã, caval); and it will pave your way towards the crown jewel of this whole set.

When you have done with these truncations, negotiate your way through a single, haunting example of a shepherd's melody, played on the caval or end blown flute. It is extraordinarily beautiful; its shifting rhythms evoke occasional memories of Dave Brubeck (sound clip - Cãnd Ciobanal si-a Pierdut Ole [When the Shepherd Lost His Sheep] - Neculi Taftã, caval); and it will pave your way towards the crown jewel of this whole set.

The jewels I refer to are the doinãs. For those unfamiliar with the term, a doinã is a form of improvised melody, with a circulation which stretches from Central Europe to East Asia, and which Alexandru compares with the blues. I suspect that his comparison originated with A L Lloyd and, in terms of conveying the mood of the doinã, it is not inept. However, the blues is cast in the same 4/4 rhythm that Brubeck was trying to bust out of, and blues melodies are not normally improvised. Therefore, even the most rural and ragged of blues interpretations sounds more regular than the melodies we encounter here. A more appropriate comparison might have been made with the field holler of the Southern United States, or with the sean nós of Gaelic Ireland. Both idioms are characterised by long drawn out melismatic lines, such as we hear with the doinã. Moreover, like the sean nós and field holler, the doinã has a capacity to sound at once mournfully dispirited and achingly beautiful. Of the five examples on this disc, four appear to have been made by amateurs for private performance. They include three unaccompanied vocals, and one instrumental melody played on a pear leaf. The fifth has the doinã decked out in all its finery. It is Mã Uitai Spre Rãsãrit ![]() (I looked toward the Rising Sun), performed by Maria Lateretu, with the Barbu Lãutaru Orchestra. It is a professional performance by gypsy musicians, and I would rank it as one of the most wonderful pieces of ethnic music ever recorded. (sound clip)

(I looked toward the Rising Sun), performed by Maria Lateretu, with the Barbu Lãutaru Orchestra. It is a professional performance by gypsy musicians, and I would rank it as one of the most wonderful pieces of ethnic music ever recorded. (sound clip)

The travail is not over yet, for the doinã section leads into a brief tangle with some of the epics and ballads of this exotic land. As with hero tale purveyors everywhere, the editors regale us with three adventures. The first, is another foreshortening, and it is particularly regrettable that this could not have been longer for two reasons. Firstly, the fragment of Colo Sus Pe Munte Verde, which means Up To The Green Mountain, is so brief as to convey absolutely nothing of its ballad character. Nor does the booklet give anything more than the barest synopsis of the story. Secondly, the singer is none other than the legendary Maria Precup. Mrs Precup is virtually unknown to western listeners, but her standing in Romanian music is very high indeed. Even more unfortunately, the disc does not include any other examples of her singing, unless she is hidden in the chorus of track 5; which was recorded in her native village of Lesu Nãsãud, Northern Transylvania.

The other two examples are monsters; as fierce and bellicose as the deeds they celebrate. One of these is the near eight minute epic referred to earlier. It is the famous Iovan Iorgovan, sung by Mihai Constantin from Southern Oltenia, ![]() and which explicates the adventures of a celebrated dragon hunter.

and which explicates the adventures of a celebrated dragon hunter.![]() 2 Its magnificent text is reproduced at the head of this review. Even in translation, it is a wonder to behold. So is the accompanying sound clip. (sound clip)

2 Its magnificent text is reproduced at the head of this review. Even in translation, it is a wonder to behold. So is the accompanying sound clip. (sound clip)

Ms Rãdulescu tells us that the example used here replaces the abridged version which appeared on the original LP. Unfortunately, she is not clear whether this is a different recording, and the point is quite important. She says that, faced with the prospect of not being able to get his entire song onto tape, Mihai Constantin indulged in some editing tricks of his own; which included chanting some of the lyrics at a fast pace, instead of singing them. I presume therefore that she is talking about the parlando passages we hear here. Whether or no, this is a mighty performance. Here be dragons indeed!

On the subject of clarity, the track notes of the original Columbias were streets ahead of an awful lot of other stuff from that period, and they have been updated for the present edition. Also, important catalogue information, omitted from the originals, has been included. However, the notes make a couple of references to 'the present day', and I am not clear whether this refers to the time the disc was first issued, or to our present day. For that matter, a brief summary of the state of folk music in twenty first century Romania, would have been helpful.

After such pinnacles, the rest of the disc feels like a climb down the other side of the mountain. Even so, there are some wonderful views, for the way leads through a field of lyrical songs. These are no less exotic than Romania's ballads and doinãs. Indeed, for all the booklet's efforts in spelling out the differences, this is one westerner who would have a hard time judging where the doinã ends and the lyric song takes up.

The final section is devoted to the music of the Lautari. They are a class of professional musicians, some of whom play ersatz gypsy music in urban cafes for town dwellers and tourists, and some of whom play authentic village music for authentic villagers. Examples of Lautari performances crop up elsewhere on this disc, most notably with Mã Uitai Spre Rãsãrit. In this section though, all but the first of these tracks seem to be of the urban variety, and they generally accord with impressions of urban lautari which I have formed elsewhere. That is to say, they are generally flashier and more virtuosic than rural musicians and, for me, they are correspondingly less interesting. The exception to that observation is Sã Lei Seama Bade Bine (Take Good Care, Sweetheart), performed by Magdalena Briescu. Her singing comes across as moving and dignified, and possessing what A L Lloyd would have called a 'fine contained passion'. Moreover, the backing is supplied by what the notes describe as a 'huge official orchestra'. If that suggests an assemblage of hacks, tempering their fire to keep the Commissariat happy, they certainly don't sound it. Indeed, their playing struck me as being informed with the same dignity and control as the singer.

Unfortunately, the effect is ruined by the track which follows it and which closes the record. It is a piece of slicked-up overdrive called Ciocârlia (The Lark), played on the pan pipes by one Fãnicã Luca. I shall not describe my withdrawal symptoms on hearing this piece. Nor shall I dwell on the fact that he reminds me of George Zamfhir at his grotty worst. I shall simply offer my amazement that the accompanists are the self same Barbu Lãutaru Orchestra, who played so magnificently on Mã Uitai Spre Rãsãrit.

Anyway, ignoring the odd Ciocârlia lurking about the grounds, are you desirous of mortgaging this most elegant property? Before you commit yourselves to the deal, I am forced to reiterate Speranta Rãdulescu's warning that the design does not meet with today's construction standards. Nevertheless, I can offer three good reasons why ethnic music fans should sign immediately. Firstly, short excerpts or no, there is some fabulous music here. It would be worth buying if came delivered in an old sack. Secondly, a lot of thought and care has gone into preparing this new edition, and it shows. Finally, while certain other countries of Eastern Europe have enjoyed the recent upsurge of interest in world music, little of that interest has focused on Romania. I'm not sure why that should be, and I can only guess at the part which the Ceausescu experience played in shaping indigenous contemporary attitudes. Nevertheless, while Romania remains a land to be discovered, there is a need for the introductory anthology - especially when it is as good as this one.

Fred McCormick - 3.10.01

Notes:

Grateful thanks are due to Lucy Castle, for her assistance in compiling this review.

| Top of page | Home Page | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |