Fiona Ritchie & Doug Orr

Wayfaring Strangers - The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia

The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. 2014. 361 pp + 20 track CD

Traditions can be tricky things. It was, I think, Samuel Johnson who said that tradition was like a meteor - once extinguished it could rise no more. When Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles visited the Appalachians in 1916 they encountered a remarkable group of people who had a lively tradition of singing and music making. Today, there are still singers and musicians to be found throughout the mountains. But is this the same tradition? Or has one tradition been replaced with another? It is, I believe, a question that could equally be applied to the world of English traditional singing. Singers such as Harry Cox, Sam Larner, Walter Pardon or Cyril Poacher were part of a tradition which had lasted for several centuries. Today, many people still sing the same songs, although the context has changed. Gone are the Saturday night singsongs in small local pubs and private kitchens, only to be replaced by the folk clubs, folk festivals, CD recordings and concert halls. Has one tradition survived, albeit in a somewhat different form, or are we now talking about two separate and discrete traditions? When I first visited the Appalachians I could still almost feel the presence of Cecil Sharp everywhere I went. There were people there who had met, and sometimes sung to, Sharp. There were certainly relatives all over the place, some of whom still sang the older songs and ballads which had so delighted Sharp and Karpeles.

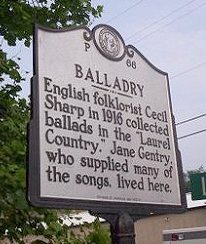

Traditions can be tricky things. It was, I think, Samuel Johnson who said that tradition was like a meteor - once extinguished it could rise no more. When Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles visited the Appalachians in 1916 they encountered a remarkable group of people who had a lively tradition of singing and music making. Today, there are still singers and musicians to be found throughout the mountains. But is this the same tradition? Or has one tradition been replaced with another? It is, I believe, a question that could equally be applied to the world of English traditional singing. Singers such as Harry Cox, Sam Larner, Walter Pardon or Cyril Poacher were part of a tradition which had lasted for several centuries. Today, many people still sing the same songs, although the context has changed. Gone are the Saturday night singsongs in small local pubs and private kitchens, only to be replaced by the folk clubs, folk festivals, CD recordings and concert halls. Has one tradition survived, albeit in a somewhat different form, or are we now talking about two separate and discrete traditions? When I first visited the Appalachians I could still almost feel the presence of Cecil Sharp everywhere I went. There were people there who had met, and sometimes sung to, Sharp. There were certainly relatives all over the place, some of whom still sang the older songs and ballads which had so delighted Sharp and Karpeles.  There was even a newly erected sign in the small town of Hot Springs, which bore the legend: Balladry. English folklorist Cecil Sharp in 1916 collected ballads in the "Laurel Country". Jane Gentry, who supplied many of the songs, lived here.

There was even a newly erected sign in the small town of Hot Springs, which bore the legend: Balladry. English folklorist Cecil Sharp in 1916 collected ballads in the "Laurel Country". Jane Gentry, who supplied many of the songs, lived here.

On one occasion Sharp collected a version of the tune The Cuckoo's Nest from a Mr Julian of Knoxville, Tennessee. Sharp later suggested that the octogenarian's tune was, originally, Irish, as was the performer whose ancestors had probably once been called Doolan. And Sharp was well aware that many of the ballads that he was collecting were similar to versions previous collected and published in Scotland by people such as William Motherwell, George Ritchie Kinloch and Sir Walter Scott. Yet, Sharp apparently appeared to ignore these facts when he published many of his collected songs as being 'English'. But, I have elsewhere pointed out that when Sharp used the term 'English' he was actually meaning 'British'. Jeremy Paxman goes into this oddity of language in his book The English: A Portrait of a People (London, 1998). At one point Sharp wrote that his Appalachian singer's ancestors were from 'the North of England, or…the Lowlands, rather than the Highlands, of Scotland' and it seems that Cecil Sharp believed that the singing traditions of England and Lowland Scotland were, to all intents and purposes, one and the same: 'For, as folk-lorists will, I think, agree, England and the English-speaking parts of Scotland must, so far as folk-tales, folk-songs, and other folk-products are concerned, be regarded as one homogenous area'. I mentioned Mr Julian above. Sharp obviously realised that this fiddle player's ancestors were from Ireland. Some of the mountain songs which he collected were, like the Scottish ballads, originally brought to American by Irish settlers. But Sharp makes little mention of Irish song collections and it is possible that he was unaware of just how common singing was in Ireland, and he may not have been aware of the song collections which had been produced there by Irish collectors.

Why am I saying all this? Well the answer can be found in this book whose subtitle, The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia, indicates that, so far as the authors are concerned, the Appalachian song tradition was one based on the material brought to the Appalachians by the so-called Scots/Irish, and the English hardly get so much as a mention. Please don't get me wrong, I am not trying to deny that a good many of the people who settled in the Appalachians were originally from Scotland and Ulster (and possibly other parts of Ireland), nor am I saying that much of the material collected by Cecil Sharp and other Appalachian collectors was not originally taken to the mountains by these people. What I do wish to say is that the situation is rather more complex than the authors of this book would have us believe. For example, at one point in the books we are told that Jack Tales are 'a British-American storytelling tradition perpetrated today in the Scottish Travelling community'. Yes, many Scottish travellers are excellent story tellers, just think of Duncan Williamson or Stanley Robertson for example, but I believe that scholars have traced many of the Appalachian Jack Tales back to Germany, rather than to Britain. (Many of the Appalachian Jack Tales can be traced to Council Harmon, whose ancestors could easily have called Hermann originally.)

Wayfaring Strangers is a hard book to review. Part coffee-table book, part story-book, it is full of beautiful colour photographs of Mountains, either in Appalachia, in Ulster, or in Scotland, together with black and white pictures of singers and musicians such as Doc Watson, Marcus Martin, The Carter Family, Shoner Benfield, Bascom Lamar Lunsford and Libba Cotton. The book is peppered with 'boxes', each one explaining some aspect or other of 'the tradition'. These include such topics as: Ballad Types, The Scottish Fiddle, Dance Music, Homesick Pioneers, Discovering Tradition Bearers, Learning Ballads and Love Songs, and Dolly Parton: A Life of Many Colors (sic). Many of these pieces have been supplied by experts such as Mike Seeger, David Holt, Pete Seeger, Jean Ritchie and Sheila Kay Adams. In fact, it is the sort of book that one finds in the stores set alongside the Blue Ridge Parkway. I am sure that many visitors to the mountains will just love this book, because it will tell them all that they wish to know. Sadly, for all its size and expertise, it does not tell the full story.

There are, I suppose, two ways of carrying out research. In the first, the researcher enters a project with as open a mind as possible. Here you note down everything that is revealed and, in the end, base your findings on what you have discovered. The second method is to enter a project with one's mind made up. Then, all you have to do is look for anything that backs up your theories at the expense of anything that contradicts them.

Fiona Ritchie has, so I am told, presented a National Public Radio show, The Thistle & Shamrock, for many years in the States, and she is clearly, and deeply, interested in the music of Scotland and Ireland. If we listen to the tracks on the CD which accompanies this book, then we will, I think, find just what she likes. The book may pay tribute to the early musical pioneers, but with one or two exceptions what we find on the CD are tracks sung and played by modern-day 'revival' singers and musicians. In other words, we are back to that old duality again. True, singers such as Bascom Lamar Lunsford and fiddlers such as Marcus Martin may not be to everyone's taste today, but they do represent a far more accurate picture of Appalachian music than some of the people heard on the CD. Why have Pete Seeger singing The Farmer's Curst Wife, when you could have had Horton Barker singing the same ballad, for example?

Doug Orr, on the other hand, is an academic at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina. As such, he should have perhaps spotted some of the mistakes that can be found in the book. Cecil Sharp, for example, lived in London, rather than in Stratford-upon-Avon, as the book says. And the comment, by Sheila Kay Adams, about Sharp 'only collecting (songs) from an older generation, people over forty' and refusing to listen to Dellie Noron 'because she was eighteen', is nonsense. In fact, Sharp collected songs from many young singers. 'Floyd Chandler sang Mathy Grove very beautifully and he is but 15', wrote Sharp on one occasion. And then there was Addie Crane, aged 21, Linnie Landers, 20, and David Norton, 17.

I said that the book has little to say about England and songs from England. The Vaughan Williams Library in London is not mentioned in the section of the book which deals with resources, although the photograph of Sharp and Karpeles noting a song from Lucindy Pratt in 1917 is printed, with an acknowledgement to the EFDSS. My other main concern with this book is that, although its contributors constantly refer to the songs and ballads that were taken to the Appalachians, there are actually very few songs and tunes given in the book. There are a few small sections which deal with the influence of black Appalachian musicians on Appalachian music in general, but there is little mention of Bluegrass or religious music, both of which are important in the story of mountain music.

If I appear to be critical towards this book, then it is because it is not the book that it could have been. It is visually a beautiful book and Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr must have worked hard to produce it. But, as I said, it does not tell the whole story and, at the end of the day, it leaves me wishing that they had only gone that extra mile or two.

Mike Yates - 10.11.14

Wiltshire

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 10.11.14

Traditions can be tricky things. It was, I think, Samuel Johnson who said that tradition was like a meteor - once extinguished it could rise no more. When Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles visited the Appalachians in 1916 they encountered a remarkable group of people who had a lively tradition of singing and music making. Today, there are still singers and musicians to be found throughout the mountains. But is this the same tradition? Or has one tradition been replaced with another? It is, I believe, a question that could equally be applied to the world of English traditional singing. Singers such as Harry Cox, Sam Larner, Walter Pardon or Cyril Poacher were part of a tradition which had lasted for several centuries. Today, many people still sing the same songs, although the context has changed. Gone are the Saturday night singsongs in small local pubs and private kitchens, only to be replaced by the folk clubs, folk festivals, CD recordings and concert halls. Has one tradition survived, albeit in a somewhat different form, or are we now talking about two separate and discrete traditions? When I first visited the Appalachians I could still almost feel the presence of Cecil Sharp everywhere I went. There were people there who had met, and sometimes sung to, Sharp. There were certainly relatives all over the place, some of whom still sang the older songs and ballads which had so delighted Sharp and Karpeles.

Traditions can be tricky things. It was, I think, Samuel Johnson who said that tradition was like a meteor - once extinguished it could rise no more. When Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles visited the Appalachians in 1916 they encountered a remarkable group of people who had a lively tradition of singing and music making. Today, there are still singers and musicians to be found throughout the mountains. But is this the same tradition? Or has one tradition been replaced with another? It is, I believe, a question that could equally be applied to the world of English traditional singing. Singers such as Harry Cox, Sam Larner, Walter Pardon or Cyril Poacher were part of a tradition which had lasted for several centuries. Today, many people still sing the same songs, although the context has changed. Gone are the Saturday night singsongs in small local pubs and private kitchens, only to be replaced by the folk clubs, folk festivals, CD recordings and concert halls. Has one tradition survived, albeit in a somewhat different form, or are we now talking about two separate and discrete traditions? When I first visited the Appalachians I could still almost feel the presence of Cecil Sharp everywhere I went. There were people there who had met, and sometimes sung to, Sharp. There were certainly relatives all over the place, some of whom still sang the older songs and ballads which had so delighted Sharp and Karpeles.  There was even a newly erected sign in the small town of Hot Springs, which bore the legend: Balladry. English folklorist Cecil Sharp in 1916 collected ballads in the "Laurel Country". Jane Gentry, who supplied many of the songs, lived here.

There was even a newly erected sign in the small town of Hot Springs, which bore the legend: Balladry. English folklorist Cecil Sharp in 1916 collected ballads in the "Laurel Country". Jane Gentry, who supplied many of the songs, lived here.