The following text has been edited from a talk which he gave at the National Folk Festival, Leicestershire, England in April 2004. In it he discusses his boyhood and family background, music making in Liverpool after the second world war, and the influences which family connections in Ireland wrought upon his repertoire.

The picture which Seán paints of Irish music in Liverpool in his formative years, differs so radically from that of most British cities that it is worth briefly commenting on. Elsewhere in Britain, post world war two building reconstruction led to a mass influx of transient Irish immigrant labour, with the immigrants coming largely from those parts of Ireland where the dance music tradition was at its most vigorous. Lacking any musical outlet to compare with the house dances they had known back home, these migrant musicians began to meet in local pubs and to play among themselves. Thus was born the 'session', an informal music making phenomenon which has nowadays become synonymous with Irish music. Its participants in those days were overwhelmingly young, male, single and mobile building workers, and who typically lived out of digs and hostels. They were young lads on the tear, moving from job to job as the occasion arose.![]() 1

1

At present there is no detailed history of Irish music in Liverpool, and what follows is based largely on conversations with Seán and my own knowledge of having grown up in the region. In any event, Liverpool musicians of that early post war period seem to have been more settled, more organised, and more closely allied to the local community and to local social institutions, than the migrant musicians just described. In particular, the main avenues of public performance in Liverpool were the Catholic church and the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge).

As Seán indicates, Liverpool Irish music making took place mainly in the home or via Gaelic League and parish organised céilís, and Seán and his confreres were first and foremost dance musicians. They were not session players and they did not play in pubs. Neither were they the direct heirs of the house dance traditions of rural Ireland, although as Seán explains, the house dance tradition in Clare came to have a major influence on his music. The musicians Seán associated with in those early days were the inheritors of a revival of Irish culture which had started among the nationalistic Irish middle class towards the end of the previous century. The fruits of that revival were by no means unique to Liverpool and would have been found among settled urban Irish populations generally. However, they were much more noticeable in Liverpool because, despite the catastrophic damage of wartime bombing, high unemployment levels made the city an unattractive proposition for Irish migrants. Thus there was nothing in Liverpool to compare with the pub sessions of London, Coventry or Manchester.

In fact, Liverpool, despite its reputation as the 'second capital of Ireland', is no longer a particularly Irish city. Although its proximity to Ireland historically resulted in huge waves of migrants settling in Liverpool, and although most of its citizens can claim some Irish ancestry, it has not, for many generations, hosted a sizeable immigrant Irish population. Therefore, where Reg Hall![]() 2 points to the succeeding generations of working class immigrants to London, who brought with them fresh waves of Irish traditions, sympathies and national identity, any comparable input into the Liverpool working class had died out by the post war era.

2 points to the succeeding generations of working class immigrants to London, who brought with them fresh waves of Irish traditions, sympathies and national identity, any comparable input into the Liverpool working class had died out by the post war era.

On the other hand, whilst Irish working class immigrants may have been put off Liverpool by high unemployment (and possible folk memories of appalling housing, social conditions and sectarian strife![]() 3, it remained one of the world's major sea ports. This was at a time when many members of the Irish middle class traditionally looked to British government organisations for employment, and Liverpool was a logical destination for entrants to the Customs Service. Thus, Liverpool continued to possess a significant Irish middle class population, with strong links to Ireland, and to Irish nationalist sympathies. For the most part these were expressed through the Gaelic League and through Gaelic League activities.

3, it remained one of the world's major sea ports. This was at a time when many members of the Irish middle class traditionally looked to British government organisations for employment, and Liverpool was a logical destination for entrants to the Customs Service. Thus, Liverpool continued to possess a significant Irish middle class population, with strong links to Ireland, and to Irish nationalist sympathies. For the most part these were expressed through the Gaelic League and through Gaelic League activities.

As a result of these factors, Liverpool Irish music making remained not just more dance oriented than elsewhere, it arguably became more institutionalised. In other parts of Britain, public houses provided the communal base and the social nexus by which transient musicians were able to meet up and play. In Liverpool, the equivalent nexus would have been achieved partly through settled kinship and communal ties, and partly through the activities of the Gaelic League.

It should be no surprise therefore to learn that the first English branch of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann was opened in Liverpool in 1957. Comhaltas possesses a centralised organisation, a strong competition ethic, and a family ethos with considerable emphasis on the training of younger musicians. None of these things would have held much attraction for the large numbers of single migrant musicians who played together informally and amorphously. The number of Irish musicians in Liverpool was comparatively small, but for the most part they were settled, they knew each other socially, their playing was channelled through formal organisations, and they had a vested interest in passing their music on to their children.

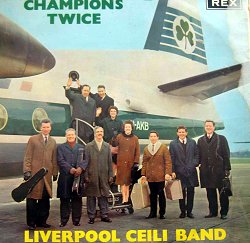

These factors may also help to explain the remarkable prestige in which Liverpool Céilí Band was held. In the admittedly partisan opinion of this writer it was the greatest céilí band ever, whose prime sadly was caught on just two long-defunct records. (Champions Twice, Rex LPR 1001, and Off to Dublin, Rex LPR 1006.) In any event, céilí bands are symptomatic of settled communities and Liverpool's settled Irish community was extremely lucky in possessing a small nucleus of first class musicians, plus one or two temporary residents such as Charlie Lennon and Tomás Ó Canainn. London, like many other British cities, had no shortage of first class musicians. What was lacking elsewhere was the communal network and the organisational infrastructure.

A retired customs officer himself, Seán and now devotes his time to teaching future generations of musicians and to performing at concerts, fleadhs, feises, céilídhs, and of course sessions. In a long life of musical activity, Seán has clocked up many achievements. One of his fondest memories, though, is appearing with the Liverpool Céilí Band on Sunday Night At the London Palladium, on St Patrick's night in 1963. In 2001, he received a special award from Comhaltas for a lifetime's dedication to music.

A devoted family man, Seán's main interest outside of his family is his music, which he describes as an "all consuming passion". Having known and enjoyed that music over many years, I totally agree.

And of course I heard the music from my older brothers playing the fiddle and I started when I was about nine. My mother played the piano and sang. She was quite a nice singer. She didn't play traditional music. She played all Moore's Melodies and that type of music. My father didn't play at all. He was a Clareman from West Clare, but I had two granduncles who were both fiddle players, who were quite noted in the area. Daniel Mac and Jamsey Mac and they were different types. Daniel Mac was supposed to be very gifted and very, how shall we say it, his music was very pure and melodic. Jamsey Mac was the one that people would ask to play for a dance because he had rhythm and, you know, that sort of thing. So there was quite a variety there, but that was where the music was in the family anyhow.

On my father's side, several of his cousins were fiddle players. But as I say, my father himself had no music. And neither did any of his brothers or sisters. It just happened that way. I went classically trained to start and I learned to play the violin at about eight or nine. But as I say, my two older brothers played Irish music, so I'd heard it a lot. And my father used to take us home to Ireland every summer to visit his home place and of course the area was full of music, and when I got into my teens I heard a lot of it. House dances were the thing in those days. There was no music in the pubs. No music in the dance halls. Whatever dance halls were there, was all ballroom dancing.

So it was in the houses that the traditional musicians played. We're talking about the '40s and the '50s. I was going to Ireland from the time I was an infant but it was in the '40s that I would be listening and going to different house dances. In the meantime, my brothers had gone off to the forces in the war, so in my development years, really, I was developing at home on my own. But because my sisters were step dancers and because Parish concerts were the standard form of entertainment in those days, I used to play for my sisters to dance. And she also taught some of the dancing in some of the different schools. So I had an early start into playing for dancing.

Then, when I was about 15, I was asked to go and play in a small céilí band at Sunday night céilís. So I started off going there. That's where I earned my first half crown. When I got home, my mother was most annoyed that I'd been playing for money. I was encouraged to play for the benefit of people listening and she was most annoyed that the priest thought I deserved half a crown. So I got half a crown a week. I think the others were getting about ten bob which was a magnificent sum in those days, but I was delighted with the half crown.

The band line up was Kathleen Osborne, who later became Kit Hodge. That was the fiddle - I was on the fiddle. And there was a pianist, Kevin Fitzgerald, and an uilleann piper. What was her name? Kathleen Doyle. Unusual again in those days for a woman to be playing the pipes. So that was the line-up. It was only a small céilí. There'd be about eighty or ninety people there. It was a regular weekly thing, and I was playing there. Then the céilís moved. Well, there was a bit of a split in the people who were organising the céilís and the group to which my family belonged moved to Wood Street![]() 4 in the centre of Liverpool. By that time my brother had come back from the forces and I was playing with him and Eamonn Coyne, young Eamonn Coyne. I say young Eamonn Coyne, he was a year or two older than me. But I mean we kind of got together. We were probably seventeen or eighteen at the time. And we got together and we were playing regularly. Then as things progressed a bit and people started coming back from the forces, there was more musicians around playing.

4 in the centre of Liverpool. By that time my brother had come back from the forces and I was playing with him and Eamonn Coyne, young Eamonn Coyne. I say young Eamonn Coyne, he was a year or two older than me. But I mean we kind of got together. We were probably seventeen or eighteen at the time. And we got together and we were playing regularly. Then as things progressed a bit and people started coming back from the forces, there was more musicians around playing.

![]() The music in Liverpool, and there was a long tradition of music in Liverpool, would be mainly polkas and jigs. We played a few, maybe half a dozen, good reels. But that was it. But I started picking up reels over in Clare on my holidays. (sound clip: Umpy Umpy)

The music in Liverpool, and there was a long tradition of music in Liverpool, would be mainly polkas and jigs. We played a few, maybe half a dozen, good reels. But that was it. But I started picking up reels over in Clare on my holidays. (sound clip: Umpy Umpy)

Eamonn Coyne and I, we did meet when we were teenagers, and we played for a while. But he had to do his national service and he went out to India. By that time of course, my brother had been demobbed, well one of my brothers, the eldest one. And, as I say, we were doing a fair bit of playing together and then Eamonn came back from his national service. He started coming on holidays with me, down to west Clare, you know. And we started picking up tunes.

The Liverpool musicians I was particularly concerned with would be, er, there was Frank Ludden and John Ludden, who were both pianists and my brother Pearse, who was quite a good fiddle player. There was one lad, well he wasn't in the army, but in fact he was a conscientious objector. He went down the mines; Séamus Ó Connor. He was also a pianist. In those days, they called them the Bevin boys. If you wouldn't go in the army, you were compulsorily sent to the mines. So he spent a couple of years working in the mines. But he was a pianist, Séamus Ó Connor. There was another fellow, Tommy Murnoch, who was also a pianist. It seemed to be that in those days, a piano was enough. There were small gatherings with no amplification, and a piano on its own was adequate. People didn't shout and make noise and all the rest of it. You know, they danced.

The Liverpool musicians I was particularly concerned with would be, er, there was Frank Ludden and John Ludden, who were both pianists and my brother Pearse, who was quite a good fiddle player. There was one lad, well he wasn't in the army, but in fact he was a conscientious objector. He went down the mines; Séamus Ó Connor. He was also a pianist. In those days, they called them the Bevin boys. If you wouldn't go in the army, you were compulsorily sent to the mines. So he spent a couple of years working in the mines. But he was a pianist, Séamus Ó Connor. There was another fellow, Tommy Murnoch, who was also a pianist. It seemed to be that in those days, a piano was enough. There were small gatherings with no amplification, and a piano on its own was adequate. People didn't shout and make noise and all the rest of it. You know, they danced.

When I started playing in Wood Street, the pianist there was a chap called Adolphus (Addie) Brophy. He was brilliant at playing the right hand, you know, playing the melodies. Wood street was a hall. The Gaelic League had regular weekly céilís there. Addie Brophy also played there, but when John Ludden came back from the army, he was a great pianist as well and he played there every week. Adolphus got paid every week, but half of the night, he just sat out, because these lads were dead keen to play. He enjoyed it, but he was happy enough for someone else to sit in and play. So there was Ned Ludden and my brother and myself. And then Eamonn came back. He was in the army in India. But when he was demobbed, he came back. So there was Eamonn and Pearse and myself. Three fiddles and Ned Ludden on the piano, mostly. Kit Hodge at that time had got married and she'd gone back to Ireland for a bit. She was down in Waterford.

So, as I say, I was mainly playing for these small weekly Sunday night céilís, and during the week there were other céilís. There were a lot of Irish priests there in Liverpool at the time, and they were all keen to have dances in their parish, and they kind of naturally had céilís, rather than ballroom dances. It was céilí dancing that they encouraged. And of course there were so many Irish - Liverpool Irish - around the place. So céilí dancing was popular, and we were playing at parishes and that sort of thing. Most of the musicians were Liverpool born of Irish descent.

A short while after that, there were at least three céilí bands in Liverpool. Kit Hodge's sister, Margaret, she ran a céilí band. She again was a Liverpool woman. Margaret Peakin, as she became. It was called the Brian Boru Céilí Band. It became noted because one time they were playing in some big dance hall at an annual St Patrick's day céilí and big notices everywhere; Brian Boru and his Céilí Band. I mean Brian Boru was 900 hundred years dead.

Peggy Peakin's band would have had a pianist. She played the piano accordion at the time. She was a pianist and fiddler and a piano accordionist. Her husband, Willie, played the drums. She had another accordion, so there were two piano accordion players, and a fiddle player in her band, you know. That was a big band. Here were we playing with two or three fiddles and a piano. And Peggy Peakin had a drum as well. There was another band, The Shannon Star around that time and again they had a piano, two piano accordions, much the same line-up. Two fiddles. They had two fiddles and drums. That was post war that they got going. Now, the two fiddle players were native Irish. Jim Terry and Jimmy Cody. They were native Irish, but living in Liverpool a good while. But as I say, we played in our small - it was quite an elite group. And, because it was the Gaelic League, it was kind of considered a little bit superior to these other groups. But it was that type of, well I wouldn't say jealousy, people would go to one where they wouldn't go the other.

When we did the occasional big dance, say around St Patrick's day or around Christmas, we had contact with a drummer. Because there was a pipe band in Liverpool, if not two, but there was certainly one pipe band there. And the drummer from the pipe band used to play with us. and also a chap on the fife, Ned Reardon. The fife was very high pitched of course. So we had a little bit of variety. But otherwise it was fiddles and piano.

In the meantime, I was developing my own music in Ireland. Every summer, I'd be going off on my holidays. And when I did my national service, I kind of wangled it that I got a travel voucher. Not a travel voucher, what did they call it?![]() 5 But anyway, I got my travel to Clare. We got three leaves a year. And I got free travel. I was going to Clare three times a year then, Christmas, Easter and summer. So I was getting very fond of the place and playing at all the house dances. I was building up my repertoire, you know. And Eamonn Coyne was coming with me as well on some of the holidays. So we were travelling around together and picking up tunes.

5 But anyway, I got my travel to Clare. We got three leaves a year. And I got free travel. I was going to Clare three times a year then, Christmas, Easter and summer. So I was getting very fond of the place and playing at all the house dances. I was building up my repertoire, you know. And Eamonn Coyne was coming with me as well on some of the holidays. So we were travelling around together and picking up tunes.

In the Parish of Kilmihil, the local players there included Miko Dick. His name was Michael Murphy, and he was Miko Dick Murphy and, er, Solus Lillis and Tom Carey. Solus Lillis was a concertina player. Michael Dick was a flute player. Michael Downes, who was from outside of the parish, but he used to come travelling around there. He was a fiddle player. Lives up in Miltown Malbay now![]() 6 Erm, there was, er, Paddy Murphy was another flute player. Miko Currane was a whistle player. When I say whistle, they had strange instruments. They weren't recorders, they weren't whistles. They were wooden instruments, you know, they seemed to drag in from somewhere or other, and there was a marvellous variety of whistles as we'd say. Not tin whistles now and not the old Clark C whistle either. But Miko Currane, he had one of these kind of timber whistles. And they were the main players. There was a famous concertina player, Stack Ryan, who was just entering his old age as we'll say. He used to travel round as well. They were the main players that I was playing with, you know.

6 Erm, there was, er, Paddy Murphy was another flute player. Miko Currane was a whistle player. When I say whistle, they had strange instruments. They weren't recorders, they weren't whistles. They were wooden instruments, you know, they seemed to drag in from somewhere or other, and there was a marvellous variety of whistles as we'd say. Not tin whistles now and not the old Clark C whistle either. But Miko Currane, he had one of these kind of timber whistles. And they were the main players. There was a famous concertina player, Stack Ryan, who was just entering his old age as we'll say. He used to travel round as well. They were the main players that I was playing with, you know.

And the house dances were something marvellous. They'd start about eight or nine o' clock in the evening, and you only went there by invite because it was a house party. Invites were sent out during the day all round the neighbourhood. And at eight or nine at night, the old people, people my age now, would go. There'd be some musicians there, but even if the musicians hadn't come, they'd have a gramophone, with Michael Coleman records and all the rest of it. All the New York musicians who were recorded then. And they'd start off the evening with the gramophone, you know. And the old people would be entertained, and the young children.

But then, maybe about 10 or 11 o' clock, the dancers would start coming in, and the musicians. And the dance would go on then 'til morning. I mean 7 or 8 when the sun was cracking the flags, they'd be dancing the last set. And when you'd be going home, you'd see the old people who'd been in there. They'd be up at that time, lighting the fires. And the young bucks like myself would be dragging ourselves into bed. Of course, my sisters used to come home to Ireland on holiday as well. And at that time there were a lot of Irish girls nursing in England as well. And they'd be home at the same time as my sisters. It was all organised every year. So of course, the families of these girls, they would organise a party. So I mean sometimes we'd be going for 5 or 6 nights on the trot.

I remember one time we were playing and one of the fiddle players was Patrick Kelly![]() 7 and Paddy McInerney who was a neighbour of Patrick Kelly's. We'd all staggered home in the morning, and because it was a lovely sunny day, my sisters decided we'd go off for a cycle trip, you know. Wouldn't go to bed, and off we went cycling down to Kilkee to the coast, and we passed Paddy McInerny's house, you know, and he was sitting up and having his breakfast, and he couldn't believe it when we went cycling past. All he wanted to do was go to bed because he had to work. That was the sort of a life that was there then.

7 and Paddy McInerney who was a neighbour of Patrick Kelly's. We'd all staggered home in the morning, and because it was a lovely sunny day, my sisters decided we'd go off for a cycle trip, you know. Wouldn't go to bed, and off we went cycling down to Kilkee to the coast, and we passed Paddy McInerny's house, you know, and he was sitting up and having his breakfast, and he couldn't believe it when we went cycling past. All he wanted to do was go to bed because he had to work. That was the sort of a life that was there then.

You know Ollie Conway of course? Ollie used to play the flute as well, but he didn't play a lot. He was more of a dancer. He didn't do so much singing then either.![]() 8 He was more of a dancer, and a marvellous dancer, he was. Ollie is a little bit older than me, but we were paddling round together a lot. Ollie's mother was a widow, and she was a bit of a task mistress, and of course it didn't matter about what time they got in in the morning. They had to get out in the fields and go to work. So Ollie would go off to the meadow, not too far from the house. But as soon as he got into the meadow, he'd lie down behind the hedge where he couldn't be seen, and sleep for the day. Because if his mother knew he was sleeping, or even knew the hour he got in. I mean, although he was a grown man, he was in his twenties at that time, himself and his brother and his sister, they were all mad for dancing. And when they used to go to bed, they used to take their best clothes into the bedroom. Then, they'd get dressed in the bedroom and go out the window and go off to the dance, and their mother would think they were in bed. And of course they got back in the same way. So, as I say, when he went off to work there, he slept in the meadow. That was the sort of carry on that was there. Nowadays, you think of the young people and the carry ons, and you think what a wicked way to be living.

8 He was more of a dancer, and a marvellous dancer, he was. Ollie is a little bit older than me, but we were paddling round together a lot. Ollie's mother was a widow, and she was a bit of a task mistress, and of course it didn't matter about what time they got in in the morning. They had to get out in the fields and go to work. So Ollie would go off to the meadow, not too far from the house. But as soon as he got into the meadow, he'd lie down behind the hedge where he couldn't be seen, and sleep for the day. Because if his mother knew he was sleeping, or even knew the hour he got in. I mean, although he was a grown man, he was in his twenties at that time, himself and his brother and his sister, they were all mad for dancing. And when they used to go to bed, they used to take their best clothes into the bedroom. Then, they'd get dressed in the bedroom and go out the window and go off to the dance, and their mother would think they were in bed. And of course they got back in the same way. So, as I say, when he went off to work there, he slept in the meadow. That was the sort of carry on that was there. Nowadays, you think of the young people and the carry ons, and you think what a wicked way to be living.

For us going from Liverpool, and away from our parents, the freedom was just marvellous, you know. I mean the whole set up, the country. I was telling someone last night that I used to go as a teenager or twenty year old, and I'd go out lying out in a field, and just lying there in sunshine, and you could hear a donkey cart, with the old iron wheels and no springs. You could hear a donkey cart maybe two miles away, and you could hear it creaking away. And you'd hear the dog barking in another direction, and birds singing and nothing else. No motor cars or anything in those days. Not even electricity or anything. And I used to think you know, how heavenly it was. It was heaven, compared with Liverpool.

There was no céilí dancing in Clare. It was all sets. And the strange thing was that at that time there were only two sets danced, what they called the Caledonian, and the Plain Set. And you'd be playing the whole night, and there would be maybe ten Caledonians to one Plain Set. Most of the people knew the Caledonian, where the plain set was only known by the good dancers. Of course, if you had a house with maybe forty or fifty men in, and maybe twenty girls. Sometimes I'd been playing where there was maybe five or six girls, and maybe thirty men, and there'd be four couples for a set. Of course the men would be mad for dancing and only four can dance at a time. So, as I say, you'd play for a Caledonian. ![]() As soon as that finished, there were four men on the floor, before you knew where you were, and they had all sorts of token gestures for the ladies. There was no kind of asking. It was just some sort of a wink or a nod. But I can remember at least one night when there were about five girls there including one of my cousins. And they were absolutely worn out, because the men just wanted to keep dancing and there weren't enough of them to ... The girls had to dance every dance, you know, right through the night. And it was something marvellous, you know. (sound clip: The Long Strand)

As soon as that finished, there were four men on the floor, before you knew where you were, and they had all sorts of token gestures for the ladies. There was no kind of asking. It was just some sort of a wink or a nod. But I can remember at least one night when there were about five girls there including one of my cousins. And they were absolutely worn out, because the men just wanted to keep dancing and there weren't enough of them to ... The girls had to dance every dance, you know, right through the night. And it was something marvellous, you know. (sound clip: The Long Strand)

The Bird in the Bush. That was a tune that not only I learned in Clare, but the Clare musicians also learned around the same time. Music was very regional in those days in Ireland you know, because, of transport and everything else. People didn't travel out far beyond their own region. So there'd be a repertoire of music in every place, you know. And somehow or other The Bird in the Bush came into the region of West Clare. I don't know where it came from. But it's a grand reel, and it just grabbed the attention of all the musicians. It was one Christmas time and I happened to be there when they were just getting hold of it. In the winter especially, they would have these wren dances![]() 9 where people would go out on St Stephen's Day on the wren and they'd collect money, and they'd spend the money on a house dance. I mean, they'd ask one of the neighbours could they use the house, and if they were foolish enough to say yes, they'd kind of take control of the house.

9 where people would go out on St Stephen's Day on the wren and they'd collect money, and they'd spend the money on a house dance. I mean, they'd ask one of the neighbours could they use the house, and if they were foolish enough to say yes, they'd kind of take control of the house.

They'd spend the money, buy a couple of casks, half casks or quarter casks of beer, and they'd buy loads of spuds and loads of baker's bread, which was considered a delicacy, you know, because everybody made their own bread. So baker's bread was considered a kind of a treat. And they'd buy ham and red jam, and that was a real party then, you know. And of course, they'd invite all the ladies. The men who were on the wren, obviously, they were in on the dance. They'd invite all the girls from the neighbouring houses. If any men who hadn't been on the wren wanted to go, they had to chip in, you know, they had to pay, because they were going to get free beer on the night. So they'd have these dances and, at that time as I say, the, what did they call the dance, the tune? The Bird in the Bush. The Bird in the Bush, you see was top of the pops. And when we'd break into The Bird in the Bush, it was like now, top of the pops. If someone came here and started playing the current pop number. But that's the way it was, a strange tune coming in, because everybody was interested in the music, dancers and everybody.

That was in the fifties. In the meantime, back in Liverpool, I was playing with three or four different groups, because there were céilís in different places, and I mean basically, there was Eamonn Coyne, Kit Hodge and myself. There was Crooky![]() 10 on the drums and there was a variety of pianists. By that time, we had a couple of younger people, Sean Murphy was playing the piano accordion. Tom Canning, Tomas Ó' Cannain as he now is, a Derryman, who came to Liverpool to study.

10 on the drums and there was a variety of pianists. By that time, we had a couple of younger people, Sean Murphy was playing the piano accordion. Tom Canning, Tomas Ó' Cannain as he now is, a Derryman, who came to Liverpool to study.![]() 11 He was playing there as well. He joined the music. Séamus Ó' Connor, who I mentioned before, he was playing in one of the céilís. So we were playing in small groups of four and five, you know. And then of course, Comhaltas in the meantime had been formed in Ireland.

11 He was playing there as well. He joined the music. Séamus Ó' Connor, who I mentioned before, he was playing in one of the céilís. So we were playing in small groups of four and five, you know. And then of course, Comhaltas in the meantime had been formed in Ireland.![]() 12 The first fleadh I went to was in Ennis, which was in Co Clare in 1956. I'd been over to a couple of the fleadhs. Well, not the first fleadh.

12 The first fleadh I went to was in Ennis, which was in Co Clare in 1956. I'd been over to a couple of the fleadhs. Well, not the first fleadh.![]() 13

13

Comhaltas is an organisation formed in Ireland to promote ... music was getting very low. In certain regions it was fine, but a lot Irish music wasn't played anywhere in a lot of parts of Ireland. So the Comhaltas was formed to revive the playing of pipes and of harp and traditional music and singing. And it was an organisation that was formed in 1951. Small group of people between Dublin and Westmeath that started it off. You heard a song last night, some of you, about Mullingar,and the first fleadh that was ever held was held in Mullingar, because it was a very central place and the people there formed that. Anyhow, we formed a branch in Liverpool in 1957![]() 14, and because they had competitions for various things, we formed a band purely to compete in the fleadhs.

14, and because they had competitions for various things, we formed a band purely to compete in the fleadhs.

And that was the Liverpool Céilí Band. And the nucleus of it was the ones who had been playing at these céilís in different groups. We all got together.

Charlie Lennon had come to study in Liverpool as well at the time.![]() 15 Then we had Sean Murphy on the piano accordion. We had Kevin Finnegan, also on the piano accordeon. Sean Murphy took up the banjo mandolin for the sake of the band, because we didn't want too many accordions, you know. And Frank Horan joined us on the button accordion and Crooky on the drums. Originally, we had a lad, Sean Maguire, playing with us, another pianist, but he was from St Helens, outside Liverpool. Sean wanted to play the melody. He wanted to play right handed and left handed, and really what we wanted for a céilí band was a vamper. And Peggy Atkins, in whose house the Comhaltas branch used to meet, took over.

15 Then we had Sean Murphy on the piano accordion. We had Kevin Finnegan, also on the piano accordeon. Sean Murphy took up the banjo mandolin for the sake of the band, because we didn't want too many accordions, you know. And Frank Horan joined us on the button accordion and Crooky on the drums. Originally, we had a lad, Sean Maguire, playing with us, another pianist, but he was from St Helens, outside Liverpool. Sean wanted to play the melody. He wanted to play right handed and left handed, and really what we wanted for a céilí band was a vamper. And Peggy Atkins, in whose house the Comhaltas branch used to meet, took over.![]() 16

16

Peggy was a very good pianist, so eventually Peggy took over on the piano with the band. The first year we played, we had a couple of St Helens lads, Billy Greenall and Billy Killgannon, with us. Then the second year, Pat (Peadar) Finn, who was a native of Roscommon, a flute player. He'd been over in England since the 1930s. Peadar is now about 85, so he was older than most of us. But he'd been all round England. Lived in Brighton. Lived in London, worked in London. Moved up to Manchester. But when he heard of our branch in Liverpool, there was a lot of infighting and jealousy in Manchester, and Peadar was a gentleman and didn't want any of that. So he came to Liverpool to live and to work, purely to join the Liverpool Céilí Band. That was his ambition and he did. He was a great contributor to it, you know.

We won two All Irelands.

We won two All Irelands.![]() 17 Well, the first success we had was the Oireachtas in 1962. The Oireachtas is a competition run by the Gaelic League in Ireland, Conradh na Gaeilge, and that was to promote the language, poetry, drama, in Irish all that, and music. So the first success we had was in the Oireachtas in Dublin, and I think there were about thirteen bands competing in that, you know, including the Tulla Céilí Band and the Kilfenora. We won that anyhow, and the following year we won the All Ireland in Mullingar. We won the All Ireland again in Clones. The third year we came second. I was happy to go along with that, but some disgruntled people thought that they wouldn't give us the third year because were from England.

17 Well, the first success we had was the Oireachtas in 1962. The Oireachtas is a competition run by the Gaelic League in Ireland, Conradh na Gaeilge, and that was to promote the language, poetry, drama, in Irish all that, and music. So the first success we had was in the Oireachtas in Dublin, and I think there were about thirteen bands competing in that, you know, including the Tulla Céilí Band and the Kilfenora. We won that anyhow, and the following year we won the All Ireland in Mullingar. We won the All Ireland again in Clones. The third year we came second. I was happy to go along with that, but some disgruntled people thought that they wouldn't give us the third year because were from England.

1966 was the 50th anniversary of the 1916 rising and was big cause for celebration in Ireland. And first of all we were invited over for the official Gaelic League céilí on Easter Sunday, which was their commemoration céilí for the '16. Then, a fortnight later we were invited over again for the official Comhaltas concert, for the jubilee celebrations, you know. And, yeah, they were great times. I can remember being there three times in about a month. Just one thing, we did compete in Thurles a little while after this, and we didn't get first, and we didn't get second and we didn't get third. But nevertheless, they had the prize winners concert in the cinema in Thurles and we had been invited to play at the concert. ![]() And the audience went mad, absolutely, although we hadn't won the competition, but the audience was marvellous. It was a better reward than winning, the reception we got. We had a few nights like that, you know. I mean, going over to the Fleadh Nua and playing in the New Hall. Two thousand people dancing to your music, you know. It was something great.(sound clip: The Kilfenora)

And the audience went mad, absolutely, although we hadn't won the competition, but the audience was marvellous. It was a better reward than winning, the reception we got. We had a few nights like that, you know. I mean, going over to the Fleadh Nua and playing in the New Hall. Two thousand people dancing to your music, you know. It was something great.(sound clip: The Kilfenora)

That was a great favourite. Of course we all had great respect, and love for the Kilfenora Céilí Band, especially me, and the one thing I couldn't understand was how we could beat them. We did beat them, but it was a constant source of wonder to me. The Kilfenora was absolutely marvellous, you know. But we accepted the judgements.

Sunday Night at the London Palladium. That was another big occasion all right.![]() 18 One of the things that did happen. It was kind of funny at the time. It wasn't funny at the time, but it was afterwards. We were all set up of course, ready to play, and we were told to start playing before they drew the curtain. Anyway, you'll know the curtain sweeps along and Crooky, the drummer was busy playing and his side drum was just inside the curtain, and didn't the curtain sweep his side drum away. Fortunately, Crooky kept his cool. And we just kept playing and Crooky got up, rescued his drum and sat down, and carried on as though nothing had happened. It was a hair raising moment for him for a short while, but as I say, the sweep of the curtain just took it off. But that was exciting as well. There was Norman Vaughan, another Liverpudlian, I think. And erm, who was it, Mavis someone or other. There was an American singer anyhow. She was the type of singer who would have sung in musical shows, you know. Was it Mamie or Marnie? I can't remember now, but it was a big American number anyhow. We were bottom of the list, and there was a group of Irish dancers, The Kavanagh School of Dancing from London. They were doing a céilí dance. We were up for them dancing. But that attracted great interest in Liverpool. There weren't any videos at that time, so it's just a memory.

18 One of the things that did happen. It was kind of funny at the time. It wasn't funny at the time, but it was afterwards. We were all set up of course, ready to play, and we were told to start playing before they drew the curtain. Anyway, you'll know the curtain sweeps along and Crooky, the drummer was busy playing and his side drum was just inside the curtain, and didn't the curtain sweep his side drum away. Fortunately, Crooky kept his cool. And we just kept playing and Crooky got up, rescued his drum and sat down, and carried on as though nothing had happened. It was a hair raising moment for him for a short while, but as I say, the sweep of the curtain just took it off. But that was exciting as well. There was Norman Vaughan, another Liverpudlian, I think. And erm, who was it, Mavis someone or other. There was an American singer anyhow. She was the type of singer who would have sung in musical shows, you know. Was it Mamie or Marnie? I can't remember now, but it was a big American number anyhow. We were bottom of the list, and there was a group of Irish dancers, The Kavanagh School of Dancing from London. They were doing a céilí dance. We were up for them dancing. But that attracted great interest in Liverpool. There weren't any videos at that time, so it's just a memory.

Then in early to mid 1970s - the headmaster of one of the nightschools

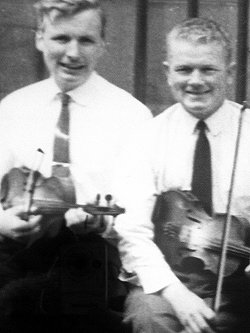

Then in early to mid 1970s - the headmaster of one of the nightschools![]() 19 was very interested in Irish music and that sort of thing. He invited Eamonn Coyne and myself to teach the fiddle. Eamonn was one of the highlights of the band as well. Eamonn was very photogenic and very charismatic. If Eamonn was in the company you would certainly know it. I mean, he played, every bit of him was going when he played, you know. And erm, and as I say, he had this beautiful cherubic smile.

19 was very interested in Irish music and that sort of thing. He invited Eamonn Coyne and myself to teach the fiddle. Eamonn was one of the highlights of the band as well. Eamonn was very photogenic and very charismatic. If Eamonn was in the company you would certainly know it. I mean, he played, every bit of him was going when he played, you know. And erm, and as I say, he had this beautiful cherubic smile.

So anyhow, er, this chap, Gus Smith, invited Eamonn and I to teach up at the night school. He was anxious to get something Irish. I mean, it was a nightschool for adults obviously, and there were things like maths, French, English, I think there was even Arabic. But there was football, there was motor mechanics. But he wanted Irish traditional music. Traditional fiddle. So he asked Eamonn and I to start the class. So we did. It was paid for by the Education Committee, and it was a very successful class. We had between 18 or 20, between the two of us. We started having two classes, and we had about 18 or 20 there, ranging from in age, probably about 50 to nearly 80. And that went on for over 20 years anyhow. And Eamonn unfortunately died in 1990, so I was left then on my own doing the classes. And that went on, the retirement age for teachers was 65. I didn't tell anyone. I mean, they knew in the office what my age was. They knew my date of birth and everything else, and the chap who was responsible for music, on the education side, he knew as well, but the classes were going well and the people were still coming, you know, and wanted it. So no-one said anything until someone in the Education Office a couple of years afterwards said, eh, this fellow should have retired a couple of years ago. He'll have to go. So I had to go. I was still obviously capable of teaching, you know. People still wanted to come to me, but that was the end of that. So somebody else took over then. But in the meantime, I'd started teaching the young, I'd teach the children, in our Comhaltas, Sunday mornings we have music classes for fiddle and accordion and whistle and flute and so we were teaching quite a few groups of children, so I teach the fiddle. I've got 5 or 6 pupils there, and have been doing that now for a number of years. So, I'm trying to pass it on.

Another activity I've been kind of roped into recently.There's a multicultural project which is funded by the government, and it's called the Greenhouse Multicultural Arts and Play Project, which is a bit of a mouthful, so we just call it the Greenhouse project, and I go out and another chap, Keith Price, Keith plays fiddle and banjo, and he comes with me, and we normally get a step dancer, a girl step dancer. And we have er, three Kurds, who come and play Kurdish music, and we go round to primary schools, you know. And each of us, I mean the Irish people, we get the kids out, dancing a 1 2 3 step around the room. A little bit of Irish dancing. And the Kurds, they play and sing Kurdish music. And they do Kurdish dancing and get the kids out, and the staff. It's great fun, you know. And we've had a belly dancer there, and African drummers. The belly dancer of course creates a great fuss with the little boys, you know. I mean, they're waggling everything they've got. Well, there's only one belly dancer, but I mean, very sensual. And all the little boys. It's funny to watch them. We know what to expect. But anyhow, erm, a belly dancer and African drummers, and African group singing - Nigerian group singing. And a Chinese lion, which is great as well. So it's a really multicultural thing.

I should mention when it comes to teaching of course, a very important thing. For the last few years I've been teaching in the Willie Clancy School as well. ![]() Anyone that's interested in fiddle music, they have a host of fiddle teachers there and we get about four hundred pupils at the workshops. So they've got about thirty teachers. So I've been helping out there for the last four or five years as well, which is a great enjoyment. It is a hard week but enjoyable. (sound slip: The Scattery Island Slide)

Anyone that's interested in fiddle music, they have a host of fiddle teachers there and we get about four hundred pupils at the workshops. So they've got about thirty teachers. So I've been helping out there for the last four or five years as well, which is a great enjoyment. It is a hard week but enjoyable. (sound slip: The Scattery Island Slide)

Seán MacNamara - April 2004

Introduction, editing and transcription, Fred McCormick - 9.10.06

2. Reg Hall, Ibid.

3. Frank Neal, Sectarian Violence: The Liverpool Experience, 1819-1914 : An Aspect of Anglo-Irish History, 1991, Manchester UP.

4. 18 to 20 Wood Street. The site now houses a 'Revolution Vodka Bar'!

5. A travel warrant.

6. Since this interview was given, Michael Downes has sadly died.

7. A famous fiddle player from Cree in Co Clare. He can be heard on Patrick Kelly from Cree, PFKC 001 (see Geoff Wallis's review) and the Comhaltas LP, Ceol an Chlár (CL 17).

8. Ollie Conway is a retired pub owner and a famous character in West Clare. He appears on the LP, The Lambs on the Green Hills, Topic, 12TS 369, and double CD Around the Hills of Clare, Musical Traditions MTCD331-2.

9. The custom of hunting the wren on St Stephen's day or Boxing day was formerly observed over large parts of Britain and Ireland. Although nowadays virtually moribund elsewhere, it continues to be observed in many parts of Ireland, including west Clare. Kevin Danaher, The Year in Ireland, 1972, Cork, Mercier Press, includes a fairly detailed account. See also The Companion to Irish Traditional Music, Fintan Vallely, ed. 1999. Cork UP. For historical eyewitness descriptions see Hall's Ireland; Mr and Mrs Hall's Tour of 1840. Sphere, London, 1984 and Patrick Kennedy, The Banks of the Boro: A Chronicle of the County of Wexford, McGlashan and Gill, Dublin, 1875.

10. Albert Cruikshank.

11. A piper, accordionist and singer who went on to found the group Na Filí. He was in Liverpool writing a thesis on mechanical engineering.

12. Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, (The Irish Musicians Association) was founded in Dublin in 1951. Its constitutional aims are to:

13. A major part of Comhaltas activity centres around the organisation of Fleadhanna Cheoil (feasts of music) at county, provincial and all Ireland level. The first national musical gathering organised by Comhaltas was held at Mullingar in 1951. It was not identified as a fleadh at the time, and the first fleadh cheoil proper was held there the following year.

14. The Liverpool branch of Comhaltas was the first to be formed in England.

15. A famous fiddler from Kiltyclogher, Co Leitrim, Charlie Lennon was with the Liverpool Céilí Band, whilst at Liverpool University, from 1960 until 1968. He's now perhaps better known as a piano accompanist.

16. Both band and branch moved to the newly opened Irish Centre in Mount Pleasant in the early 1960s and remained there until the Centre closed in 1997. The Liverpool Comhaltas branch is now based at St Michael's Irish Centre in Everton.

17. 1963 and 1964.

18. St Patrick's night, 1964.

19. The Roscommon Institute in Shaw Street, Liverpool.

Article MT190

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |