Article MT214

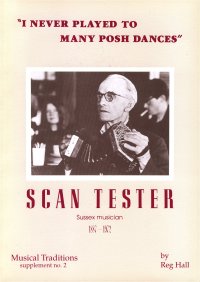

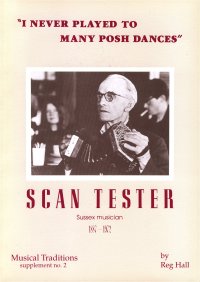

Scan Tester

The Reg Hall BBC Radio Sussex interviews

On 30th October 1990, Reg Hall came into the BBC Radio Sussex studios in Brighton to record an interview with me for the station’s folk music programme Minstrels Gallery about Scan Tester and the I Never Played To Many Posh Dances project which had recently been published and released. It was such an important event in music circles locally that we decided to devote the majority of two programmes to it.

On 30th October 1990, Reg Hall came into the BBC Radio Sussex studios in Brighton to record an interview with me for the station’s folk music programme Minstrels Gallery about Scan Tester and the I Never Played To Many Posh Dances project which had recently been published and released. It was such an important event in music circles locally that we decided to devote the majority of two programmes to it.

The format for both programmes was to be that we would play four tracks from the LPs and intersperse them with three sections of interview. Apart from a few station identity announcements and repeating the publication/record label details, I have transcribed the interview in full. There are a few places where I would have liked to have questioned Reg more fully about what he was saying, and probably would have had this not been a radio programme with the consequent constraints on time. Nevertheless, I feel that Reg had much to say which augments the facts and information that are contained in the book and adds to our understanding of this seminal figure.

Hoping that the appearance of this interview might stimulate interest and sales of the book and record, I made some enquiries about the availability of both and came up with the following information:

- Tony Engle of Topic records (www.topicrecords.co.uk) states that the vinyl albums are now sold out, but that they are hoping to be able to release the albums on CD some time in the future.

- John Howson of Veteran Mail Order (www.veteran.co.uk) has both the book and the albums (in double cassette form) available for sale from his website.

- Peta Webb of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (www.efdss.org/library.htm) has some copies of the book available for sale. They are on the basis of donated stock: sales go down as donations to the library, not to EFDSS generally.

Vic Smith

First programme

Side 3 Track 9, Jig: - Irish Washerwoman - Scan Tester, concertina

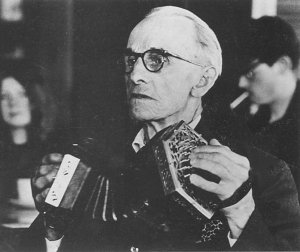

And that’s the Irish jig, The Irish Washerwoman, played by a Sussex musician, the late Scan Tester, and we are starting now, a fairly lengthy feature for us on Minstrels Gallery on the life and times and music of Scan Tester and the reason for this is a recently published book and, released in connection with it a double album. Scan Tester - I Never Played To Many Posh Dances is the title of both the book and the double record. And to help us through this is the man responsible for both the book and the records, Reg Hall. First of all, Reg, welcome to Minstrels Gallery.

It’s nice to be here.

Now, quoted on both the book and the record are Scan’s dates - born in 1887, died in 1972. At what stage in Scan’s life did you come to know him?

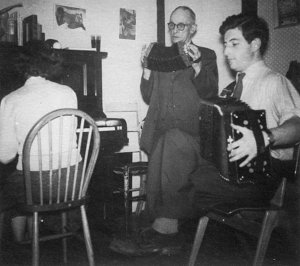

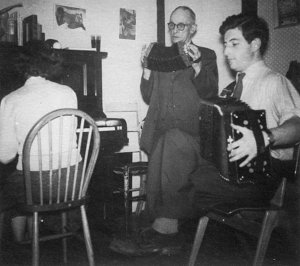

Well, I met him in 1956 when I was about 23. It happened that I used to go and stay with a friend of mine, Mervyn Plunkett. He had a house in West Hoathly. We used to go and play in the pubs around there on Saturday nights. Well I was staying at that house and on this particular day, it was about 5 o’clock on a Saturday afternoon and I was playing some tunes in the back room and the greengrocer came to the back door to deliver the greengrocery and he heard me playing. And he said, “Who’s that playing?” and he was told who I was and he said, “Well, my wife’s father plays just like that.” And his wife’s father was Will Tester who was Scan’s brother. And that led us to Scan and within three weeks, Mervyn has been round to see Scan who lived about three miles away in Horsted Keynes and Mervyn recorded two or three pieces and within a few weeks, I had met him as well and we were playing together.

Well, I met him in 1956 when I was about 23. It happened that I used to go and stay with a friend of mine, Mervyn Plunkett. He had a house in West Hoathly. We used to go and play in the pubs around there on Saturday nights. Well I was staying at that house and on this particular day, it was about 5 o’clock on a Saturday afternoon and I was playing some tunes in the back room and the greengrocer came to the back door to deliver the greengrocery and he heard me playing. And he said, “Who’s that playing?” and he was told who I was and he said, “Well, my wife’s father plays just like that.” And his wife’s father was Will Tester who was Scan’s brother. And that led us to Scan and within three weeks, Mervyn has been round to see Scan who lived about three miles away in Horsted Keynes and Mervyn recorded two or three pieces and within a few weeks, I had met him as well and we were playing together.

Were you in contact with any other Sussex pub musicians at the time?

No, he was the first musician we had come across. We had met loads of singers, Pop Maynard and George Spicer - Mervyn found both of those. Pop Maynard came from Copthorne on the Surrey border and George Spicer came from just outside West Hoathly. They were great singers. There was lots and lots of other singers around, and some of them were just one song singers, but there were no musicians; we didn’t actually hear any music. I used to go along to these sessions to provide the music. We saw just the last knockings of step dancing, and I think on one occasion, we were in a pub and someone picked up a tray, tin tray, you know, that they serve the beer on and he played it like a tambourine, like the Irish play the bodhrán now. That was a revelation to me. And then, of course, we met Scan and we realised the whole history of the music.

When you were told that there was someone who played like you, was that the case? Do you think that your playing was like Scan’s?

No, I don’t think it did; No, I had learned from else where and actually on the record, you can hear me playing La Russe and, of course, it’s a imitation of Peter Kennedy’s playing, because I learned it off his records. The people who had inspired me were people like George Tremain 1 from Yorkshire and Bob Cann who had even then had made quite a number of BBC recordings.

1 from Yorkshire and Bob Cann who had even then had made quite a number of BBC recordings.

Scan and I had enough in common. When we met we could actually play together; but he changed my rhythm. He actually told me how to play; he taught me to do it quite differently.

What was your reaction - musically - to finding an old Sussex pub musician? You must have suspected that there were some around.

I’d hoped that there were some around. I’m not so sure that I suspected that there were. By as we came across Scan, it happened that we came across quite a few others. It was as if, once the lid had come off, there were all the others under the surface. The tragedy was that there were other musicians that I did not know about. There were whole nests of fiddle players and I never knew about them until it was much too late.

Well, I intend to include as much music as we can in this feature, Reg, so let’s listen to Not For Joe. Any comments on that particular tune?

Well, that’s an old-fashioned polka. It was written by ... well I can’t remember off-hand, I don’t carry these things in my head … but we do know who wrote it 2 and it’s (about) Joe Chamberlain, what was he? Colonial Secretary at one time and the mayor of Birmingham

2 and it’s (about) Joe Chamberlain, what was he? Colonial Secretary at one time and the mayor of Birmingham 3 and this was a music hall song and likes lots of these old-fashioned tunes, the ones that Scan played, they were from commercial music, but he and his pals knocked them into shape so this is Scan Tester’s version of Not For Joe.

3 and this was a music hall song and likes lots of these old-fashioned tunes, the ones that Scan played, they were from commercial music, but he and his pals knocked them into shape so this is Scan Tester’s version of Not For Joe.

Side 2 Track 5. Polka: Not For Joe - Scan Tester, concertina

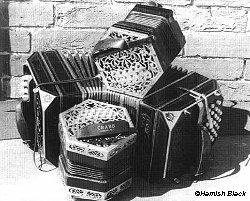

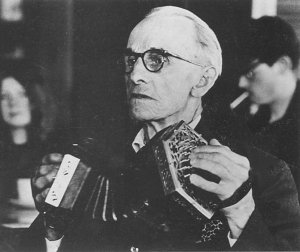

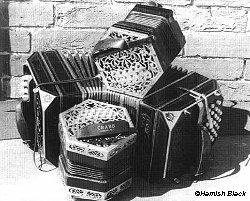

Not For Joe played by Scan Tester on the Anglo-concertina. Reg, we’ve heard Scan Tester playing a jig and now a polka; are we to learn from this that Scan was primarily a musician who played for social dances?

I think very much that’s right. He could play songs and later in his life, he played for sing-songs in pubs; he could always follow anybody, but essentially, he was a dance musician. He started very early in life. He was about eight when he started playing the tambourine and he learned the tambourine from his uncle who was born about 1826. His uncle was about sixty-five and Scan was eight and they went around as a pair! But they had a third member; a trio as it were. That was Scan’s older brother Trayton, who was another concertina player and I suspect, though I’ve got no real evidence, that he was also a fiddle player. And he could play the cornet and Scan said that was a knock-out on any instrument. That was the trio. Trayton was about twenty-three, the old man of sixty-five and the boy of eight and that was the pub trio. They went around different pubs playing.

I think very much that’s right. He could play songs and later in his life, he played for sing-songs in pubs; he could always follow anybody, but essentially, he was a dance musician. He started very early in life. He was about eight when he started playing the tambourine and he learned the tambourine from his uncle who was born about 1826. His uncle was about sixty-five and Scan was eight and they went around as a pair! But they had a third member; a trio as it were. That was Scan’s older brother Trayton, who was another concertina player and I suspect, though I’ve got no real evidence, that he was also a fiddle player. And he could play the cornet and Scan said that was a knock-out on any instrument. That was the trio. Trayton was about twenty-three, the old man of sixty-five and the boy of eight and that was the pub trio. They went around different pubs playing.

I suppose that today people will think of social dance taking place in dance clubs and at barn dances, what would have been the actual locations that Scan would be likely to have played at in his early days?

Well, I think almost exclusively, the tap-room of a pub. There weren’t village halls in those days. If you think about it, most village halls are called ‘memorial halls’ and they were all memorials to the poor fellows who died in the Great War, so they were all built in the ‘20s. There were no village halls. There were a few ‘reading rooms’, these were for working men in the villages and they were often subscribed by the gentry or by the working men themselves. They might have been big enough to assemble in and have a dance or a party, but mostly Scan, very early on in his career played in the tap-rooms of pubs to an almost exclusively male audience.

So it would be step dance tunes … hornpipes … mainly to suit that type of thing.

Hornpipes…. the odd 6/8 tune. I’m not really sure that Scan ever used the word ‘jig’ 4. I’m not sure that he would call The Irish Washerwoman a jig…. But he called the hornpipes, step dance tunes. That was the great thing, especially in the pubs over in Ashdown Forest, at Nutley and Fairwarp, and it’s interesting that Scan at 10, 12, 13, 14, he used to go off about four or five miles specifically to learn music; the tunes. And he learned, he said, from men that were in their seventies or eighties. And so he knew that he was playing old-fashioned music then.

4. I’m not sure that he would call The Irish Washerwoman a jig…. But he called the hornpipes, step dance tunes. That was the great thing, especially in the pubs over in Ashdown Forest, at Nutley and Fairwarp, and it’s interesting that Scan at 10, 12, 13, 14, he used to go off about four or five miles specifically to learn music; the tunes. And he learned, he said, from men that were in their seventies or eighties. And so he knew that he was playing old-fashioned music then.

Side 1 Track 6 - No.2 Step Dance Tune - Scan Tester, concertina

So we are talking about tunes and a tradition that must go back at least 150 years from now …

I’d guess to the end of the 18th century. But the pubs … you see, it was really the Beer House Act of 1830 5 that started it. Before that there were tap-rooms and there were inns, but the pubs that scatter the whole of southern England, they all date from that time, so that pub culture came to life then and what had gone on at weddings and at the tap-rooms of inns really blossomed from 1830 onwards

5 that started it. Before that there were tap-rooms and there were inns, but the pubs that scatter the whole of southern England, they all date from that time, so that pub culture came to life then and what had gone on at weddings and at the tap-rooms of inns really blossomed from 1830 onwards

Well. I’m going to come back to Reg Hall and Scan Tester next week, but for now I’d like to give you details of the record. The double album is available on the Topic label - Scan Tester - I Never Played To Many Posh Dances and the accompanying volume is in the imprint of Musical Traditions Supplement No.2 by Reg Hall under the same title. You should be able to buy or order this in record shops. If you have any difficulty at all, drop us a line - address as always at the end of the programme - and I will pass the enquiries on to Reg. For now, Reg, we will end this feature this week with a step dance tune and I see from the label that this was recorded at The Fox in Islington. Tell us about the music at that pub before we hear the tune.

Well, that’s a great jump! The Fox was really an ‘anti-folk club’. I suppose that it was part of the folk club movement, but we actually wanted to do it in a way that was totally different from the standard way that a folk club would be run and we didn’t even call it a folk club. It was just called ‘The Fox at Islington’

So, what sort of singers and musicians would be heard at this ‘anti-folk’ club?

Well, we got people like ‘Shrimp’ Davies, who was the coxswain of the Cromer Lifeboat. He was a step-dancer and singer. We got Punch & Judy artists, we got the local concertina bands, but we had all the people like Bob Roberts and Fred Jordan and people like that and we had a lot of the Irish people from the local London Irish community.

And on 21st January 1965, you had Scan Tester …

Side 2 Track 9 - Step Dance Tune - Scan Tester, concertina

Second programme

Side 1 Track 5. Waltz: - The Man In The Moon - Scan Tester, concertina

The waltz The Man In The Moon played on the anglo-concertina brings us into our second feature on the times and music of Scan Tester of Horsted Keynes and helping us is the man responsible for the book and double LP I Never Played To Many Posh Dances and, of course, we welcome back the man responsible for these, Reg Hall to tell more of Scan’s story.

I daresay, Reg, that you would be delighted to hear that the tune we’ve just heard, The Man in the Moon, is a very popular one in tune sessions in and around Sussex today.

Well, I had no idea of that. I imagine that they have all got it from Scan in one way or another…

Well, I had no idea of that. I imagine that they have all got it from Scan in one way or another…

Oh! Undoubtedly, musicians like Jean Addison, Vic Gammon, Will Duke have listened to Scan or recordings of Scan and have introduced it into pub sessions and now it’s very popular.

Scan would be pleased.

He certainly would be. He would have wanted to join in; he seemed to love playing with younger musicians. There never seemed to be an age barrier with him. You talked last week about him playing with older musicians when he was a boy, as an old man, he liked to play with younger musicians.

Yes, I don’t think that anyone noticed the age gap.

Something else that you talked about last week was playing at a pub called The Fox in Islington … I’ve been aware in reading this book that you don’t - when you are talking about Scan - call him a ‘folk musician’. I don’t think that you even call him a ‘traditional musician’, do you?

Well. I went out of my way not to call him a traditional musician. I thought that trying to categorise him wouldn’t help with who he was and what he did and how he did it. I actually think of him as a traditional musician, but I wouldn’t like to have to define to you what a traditional musician is. I’ve actually got a very clear idea in my own mind, but I actually reject the whole notion of folk song and folk dance. I don’t think that it helps. I think it was something that imposed from the outside on the culture and that it is misunderstood and I don’t really think of it as a valid way of describing anything, so in my own conversation, I haven’t used the word ‘folk’ since 1959. I accept that there is such a thing as a folk song movement and a folk dance movement and that is that only way that I use it in the book - when I talk about those movements.

So there’s a mismatch between Scan and the other musicians around Horsted Keynes and what happens in folk clubs.

Oh, I think that it is a different world. Talk about The Man In The Moon … they are two different worlds. I mean the ‘folk revival’ and the tradition are two quite different things.

So what was the natural habitat for Scan’s music?

Scan was a working man. He was making music for his own community and it came out of his own community and the demand was from his own community, so for him that meant playing in a pub.

Would it have been a written music …

Oh, not the way Scan played it … Go on, ask your question.

Well, a written music or an aural music.

I think that there were two traditions. If you were to look at Scan’s contemporaries; the people that he was brought up with. He was born in the 1880s and the music within his family goes back through his brother who was much older and his uncle who was two generations older than that and they belonged to the aural tradition. There’s no question in my mind about that. They had the old songs, the old step dancing, the old country dances, the old music and it was all by aural transmission, there is no question of that.

It changed; they picked up music all the time during their lives. They constantly added to the music; they changed it, but it was an aural tradition. But their contemporaries and their peers, perhaps their neighbours, perhaps the members of their families - they had the music that comes from literate sources, and after Waterloo there was this brass band movement that swept the country 6 and suddenly working men were beginning to read, not only tunes, but parts, so that was a different music and I try to explore that in the book. These two traditions existed side by side, so Scan might learn from a barrel organ, a fairground organ, which belonged to the written music tradition side of things, but would also pick up tunes from Gypsies who were on the aural side of things. He straddled both.

6 and suddenly working men were beginning to read, not only tunes, but parts, so that was a different music and I try to explore that in the book. These two traditions existed side by side, so Scan might learn from a barrel organ, a fairground organ, which belonged to the written music tradition side of things, but would also pick up tunes from Gypsies who were on the aural side of things. He straddled both.

And he learned from both?

Yes, but his feet were very firmly in the camp of the aural tradition.

You’ve talked about Scan’s being a musical family … we are going to come on to hearing him play in the company of his brother.

Side 1 Track 7 Schottische - Scan and Will Tester, concertinas

Scan and his brother Will Tester recorded playing in a popular music pub at the time, The Trevor Arms at Glynde 7 and that pub is still there.

7 and that pub is still there.

Oh yes, I was in there only last year.

Now the next recording that we are going to listen to is Scan playing with some percussive accompaniment and this was something that you were talking about last week.

Well, the old fashioned dance music that Scan was brought up with was linear; it was just a tune and all the rhythm was contained in the melody. And the way he articulates and breaks it up into phrases is all to do with keeping the rhythm and the momentum going. It is the same in Ireland, I’m sure it is right the way through the British Isles. All of Scan’s mates played, as far as I can understand, in this linear way. The only other instruments that were around were percussive and the way that they used percussion was on equal terms with the melody. It was there to get the drive, to get the momentum, to move it and keep the rhythm going. Quite unlike brass band drumming which is there to underline the basic beat or classical symphony playing where it is there for the tone colour or dramatic emphasis. This is percussion that is there to drive the music and very very common, spoons, bones, tambourines; people tend to think of the bodhrán being Irish but tambourines were very common right across southern England and a very similar style to the way the Irish people play it now. I wouldn’t like to say whether it was Irish or English, I don’t really think it matters

Now today we tend to think of the tambourine as the small instrument played in junior schools …

No, no, they were enormous, often two feet across. Scan’s uncle has one that was two foot across and it had three bells on it and when he was playing it, he could ring whichever bell he wanted, so he had quite a bit of skill.

So who are the musicians with him on The Monkey Hornpipe?

Well it’s basically Scan on the concertina, and Bill McMahon, a spoons player, who still lives in West Hoathly. He’s a Liverpudlian and a great spoons player. He was a relatively young man in those days. 8

8

Side 3 Track 10. Stepdance: The Monkey Hornpipe - Scan Tester concertina, Bill McMahon spoons/effects, Mervyn Plunkett percussion

The Monkey Hornpipe, Scan Tester of Horsted Keynes on Anglo concertina and Bill McMahon of West Hoathly on spoons and “effects” - and the “effects” - what is he doing? Is he slapping his cheeks? What is he doing?

He was hitting his hands together in front of his mouth. He would open his mouth and by changing the shape of his mouth, he could alter the pitch so that he could clap a harmony part!

It must have been quite a visual thing apart from anything else!

Yes, another of his tricks was to turn the spoons around and hit the handles together so that it sounded like a triangle. Well, you are asking me about the percussion, one of the things that hit me going around in the 1950s in that area was that you only had to start playing music in a pub and the percussion came from nowhere, thimbles on the table or a penny on a pint glass, a whole range of things …

Trays …

Yes, but the real thing was that they had this really tremendous percussive rhythm and none of this clapping on the beat that you get in the media or in the movies. Nobody ever clapped on the beat; that would have killed it dead. No, they were much more inventive.

When I first heard you talking about the possibility of producing a record of Scan…. I think Scan was still alive. He died in 1972, so this has taken many years to come to fruition. And I suppose I have been particularly surprised by accompanying book, I Never Played To Many Posh Dances. But then I think you would be surprised by the size of it if you go back to your original idea.

Yes, it is a surprise to me that it has turned out the way it has. I think I’d want to go back to discuss my relationship with Scan. I think that when I met him, he was a musician and I was a musician and we got on together and it never occurred to me that he should be the subject of a project. So that when round about 1966, I thought, “Scan’s so good that we ought to have some recordings issued” and I was going to issue them privately in 1966 and I thought then of a double album. And it was really… as an evangelist.  I really wanted to say there is this marvellous music around and Scan is just a part of it. He is just one of the musicians. It never occurred to me that it was really dying; that this was the end of it. Somehow, I thought that we could move the world on; that if people heard Scan and all these other musicians - and I could list dozens and dozens of them - that the world would be a better place and we’d move on and everyone would be playing that sort of music. Of course, it didn’t happen like that.

I really wanted to say there is this marvellous music around and Scan is just a part of it. He is just one of the musicians. It never occurred to me that it was really dying; that this was the end of it. Somehow, I thought that we could move the world on; that if people heard Scan and all these other musicians - and I could list dozens and dozens of them - that the world would be a better place and we’d move on and everyone would be playing that sort of music. Of course, it didn’t happen like that.

Then came a point, round about 1970, when I was discussing the double album with a record company and that company couldn’t actually produce the record. And then I went into the doldrums. I lost heart and I didn’t even think about it for ten years. I filed everything away; I didn’t listen to the tapes. didn’t do any work at all. And then some enthusiasts, people like Tony Engle, Keith Chandler, yourself, were all saying to me about four years ago that I must get these records issued because people would want to hear this stuff. And that started me thinking. I’ve gone through years of thinking about it. And I was now thinking of it more as a historian than an evangelist; a musician who wants to change the world.

So it was four years ago that you started working on it again.

I said to Tony Engle 9 “I think I will take three months to do it.” With the notes to put in the LP sleeve - and now it has turned out to be 150 pages - 60,000 words! But I must say, Vic, that a lot of it is transcribed interview and that some of it was from you.

9 “I think I will take three months to do it.” With the notes to put in the LP sleeve - and now it has turned out to be 150 pages - 60,000 words! But I must say, Vic, that a lot of it is transcribed interview and that some of it was from you.

Well, yes, that’s right.

I think that you probably knew him better than I did.

Oh! I don’t think that I did! We certainly used to go up to see him 10 and I think we were just lucky to have caught him a very reflective mood one Sunday afternoon and we were lucky enough to have our tape recorder with us. He really seemed want to talk and seemed to be remembering things quite clearly.

10 and I think we were just lucky to have caught him a very reflective mood one Sunday afternoon and we were lucky enough to have our tape recorder with us. He really seemed want to talk and seemed to be remembering things quite clearly.

Well, no, I think that is quite interesting. I saw him as a friend and not someone that I should try and interview and do a project on, but I was cute enough that whenever the tape recorder was around, I let it run and most of the material that I quote comes from one morning in my kitchen when he was very talkative, just as you found him doing the same sort of thing.

We can’t go much further now without hearing the man’s voice himself. Here is Scan explaining one of his dances - The Broom Dance - and after that we will hear him playing the music for the dance in the company of Reg Hall on melodeon and Scan’s daughter, Daisy Sherlock on piano.

Well, they - er - had a broom back and they cocked their legs and they’d take it from one hand to another, both legs and then they walked to and fro - sort of waltzed to and fro, you see, one part, the other part, you see, and then they’d come back and do it over again. See? Well, it’s all the two parts over and over again. But, very often, there was four of them together do it, you see, and then they’d go in an out one another, you see, two each end and then they’d do it again.

Side 1 Track 3 The Broom Dance - Scan Tester concertina, Reg Hall melodeon, Daisy Sherlock piano

Notes:

1 - From North Skelton, North Yorkshire. Hear him and read a short biography on the VotP album To Catch a Fine Buck Was My Delight. (Topic TSCD 668)

2 - In 1867 Arthur Lloyd wrote and composed another big hit with the public, Not for Joe. See www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/NotForJoe.htm I cannot find a reference to this song being about Chamberlain.

3 - Joseph Chamberlain (July 8, 1836 - July 3, 1914) See www.birminghamuk.com/wikipedia/Joseph_Chamberlain.htm

4 - Sorry, Reg, but on page 79 as part of an interview with me, Scan is quoted as saying “Most people like them old jigs, you know. I used to know several Irish and Scottish jigs, but they’ve all gone.”

5 - The Beer House Act saw a swathe of 'beer-only' premises open across England and Wales with extended trading hours, from 4am to 10pm.

See www.24hourmuseum.org.uk/exh_gfx_en/ART38026.html

6 - The keyed bugle was invented in Dublin, Ireland. It caught the public's eye in 1815 when it appeared at celebrations following the Battle of Waterloo. This new chromatic brass instrument was an improvement on the common field bugle and soon became known as the 'Kent Horn' because its inventor, Joseph Halliday, dedicated his creation to his military commander, the Duke of Kent. As various military bands adopted the chromatic bugle, the stage was set for a new musical ensemble, the all-brass band, to sweep Europe. As early as 1816, the keyed bugle can be documented in America at the Military Academy at West Point. Ensembles of all brass instruments became typical for military bands the world over. See www.harrogate.co.uk/harrogate-band/misc10.htm

7 - The Trevor Arms still offers the opportunity to hear traditional tunes as a couple of monthly sessions are still held there. And as one of the sessions is led by Will Duke, the pub still echoes to the sound of the anglo-concertina which Scan Tester once played.

8 - The track listings also give Mervyn Plunkett playing percussion on The Monkey Hornpipe.

9 - Head of Topic Records.

10 - By this time, Scan was living with his daughter, Daisy and her husband, Archie Sherlock, in a cottage in Horsted Keynes.

13.4.08

Article MT214

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 18.4.08

On 30th October 1990, Reg Hall came into the BBC Radio Sussex studios in Brighton to record an interview with me for the station’s folk music programme Minstrels Gallery about Scan Tester and the I Never Played To Many Posh Dances project which had recently been published and released. It was such an important event in music circles locally that we decided to devote the majority of two programmes to it.

On 30th October 1990, Reg Hall came into the BBC Radio Sussex studios in Brighton to record an interview with me for the station’s folk music programme Minstrels Gallery about Scan Tester and the I Never Played To Many Posh Dances project which had recently been published and released. It was such an important event in music circles locally that we decided to devote the majority of two programmes to it.

Well, I met him in 1956 when I was about 23. It happened that I used to go and stay with a friend of mine, Mervyn Plunkett. He had a house in West Hoathly. We used to go and play in the pubs around there on Saturday nights. Well I was staying at that house and on this particular day, it was about 5 o’clock on a Saturday afternoon and I was playing some tunes in the back room and the greengrocer came to the back door to deliver the greengrocery and he heard me playing. And he said, “Who’s that playing?” and he was told who I was and he said, “Well, my wife’s father plays just like that.” And his wife’s father was Will Tester who was Scan’s brother. And that led us to Scan and within three weeks, Mervyn has been round to see Scan who lived about three miles away in Horsted Keynes and Mervyn recorded two or three pieces and within a few weeks, I had met him as well and we were playing together.

Well, I met him in 1956 when I was about 23. It happened that I used to go and stay with a friend of mine, Mervyn Plunkett. He had a house in West Hoathly. We used to go and play in the pubs around there on Saturday nights. Well I was staying at that house and on this particular day, it was about 5 o’clock on a Saturday afternoon and I was playing some tunes in the back room and the greengrocer came to the back door to deliver the greengrocery and he heard me playing. And he said, “Who’s that playing?” and he was told who I was and he said, “Well, my wife’s father plays just like that.” And his wife’s father was Will Tester who was Scan’s brother. And that led us to Scan and within three weeks, Mervyn has been round to see Scan who lived about three miles away in Horsted Keynes and Mervyn recorded two or three pieces and within a few weeks, I had met him as well and we were playing together.

I think very much that’s right. He could play songs and later in his life, he played for sing-songs in pubs; he could always follow anybody, but essentially, he was a dance musician. He started very early in life. He was about eight when he started playing the tambourine and he learned the tambourine from his uncle who was born about 1826. His uncle was about sixty-five and Scan was eight and they went around as a pair! But they had a third member; a trio as it were. That was Scan’s older brother Trayton, who was another concertina player and I suspect, though I’ve got no real evidence, that he was also a fiddle player. And he could play the cornet and Scan said that was a knock-out on any instrument. That was the trio. Trayton was about twenty-three, the old man of sixty-five and the boy of eight and that was the pub trio. They went around different pubs playing.

I think very much that’s right. He could play songs and later in his life, he played for sing-songs in pubs; he could always follow anybody, but essentially, he was a dance musician. He started very early in life. He was about eight when he started playing the tambourine and he learned the tambourine from his uncle who was born about 1826. His uncle was about sixty-five and Scan was eight and they went around as a pair! But they had a third member; a trio as it were. That was Scan’s older brother Trayton, who was another concertina player and I suspect, though I’ve got no real evidence, that he was also a fiddle player. And he could play the cornet and Scan said that was a knock-out on any instrument. That was the trio. Trayton was about twenty-three, the old man of sixty-five and the boy of eight and that was the pub trio. They went around different pubs playing.

Well, I had no idea of that. I imagine that they have all got it from Scan in one way or another…

Well, I had no idea of that. I imagine that they have all got it from Scan in one way or another…

I really wanted to say there is this marvellous music around and Scan is just a part of it. He is just one of the musicians. It never occurred to me that it was really dying; that this was the end of it. Somehow, I thought that we could move the world on; that if people heard Scan and all these other musicians - and I could list dozens and dozens of them - that the world would be a better place and we’d move on and everyone would be playing that sort of music. Of course, it didn’t happen like that.

I really wanted to say there is this marvellous music around and Scan is just a part of it. He is just one of the musicians. It never occurred to me that it was really dying; that this was the end of it. Somehow, I thought that we could move the world on; that if people heard Scan and all these other musicians - and I could list dozens and dozens of them - that the world would be a better place and we’d move on and everyone would be playing that sort of music. Of course, it didn’t happen like that.